Abstract

Little is known about the psychological state of those who leave a stigmatized group. We examined individuals who previously belonged to a stigmatized group, the overweight, and then became normal weight. Negative stereotypes, including those relating to obesity, are internalized from the time of childhood onward; therefore, it was assumed they would become lingering self-stereotypes among individuals who were no longer externally targeted. Drawing on a nationally representative sample, we examined for the first time whether formerly overweight individuals are susceptible to any anxiety disorder, any depressive disorder, and suicide attempts. As predicted, the likelihood of any anxiety disorder and any depressive disorder for the formerly overweight group was significantly greater than for the consistently normal-weight group, and not significantly different from the consistently overweight group. Further, the formerly overweight group was significantly more likely to attempt suicide than the other groups. Also as predicted, perceived weight discrimination partially mediated the relationship between weight status and these outcomes. The cohort consisted of 33,604 participants in the United States. The results suggest that losing a self-image shaped by stigma is a more protracted process than losing weight.

Keywords: United States, Stigma, Discrimination, Mental health, Obesity, Overweight, Anxiety, Depression, Social determinants

Introduction

The psychological effects of membership in stigmatized groups have been extensively investigated (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, 2009;Levy, 2009; Link & Phelan, 2001), yet little is known about the psychological state of those who leave stigmatized groups. In the present study, we examined individuals who have undergone this transition: from overweight to normal weight.

Although formerly overweight individuals have made a socially valued transition, we expected to find that lingering effects of the prior membership in a stigmatized group would generate psychological distress. This assumption was derived from combining and extending several previous findings: (a) the labeling that is associated with stigma can have an enduring effect on well-being (Link, 1987; Link, Struening, Rahav, Phelan, & Nuttbrock, 1997); (b) overweight children and adults are likely to have internalized the negative obesity stereotypes that are prevalent in society (Davison, Schmalz, Young, & Birch, 2008; Wang, Brownell, & Wadden, 2004); (c) these stereotypes correlate with psychological distress in overweight individuals (Friedman et al., 2005); (d) negative self-stereotypes, reinforced by discrimination, tend to comprise a stable component of self-images (Levy, Slade, Kunkel, & Kasl, 2002); and (e) this stability is reflected in the phenomenon called “phantom fat,” whereby negative views about appearance persist in formerly overweight individuals (Stunkard & Burt, 1967).

Drawing on a nationally representative sample, we examined for the first time whether formerly overweight individuals are susceptible to any anxiety disorder, any depressive disorder, and suicide attempts. We predicted that the likelihood of these outcomes for the formerly overweight group would be significantly greater than for the consistently normal-weight group, but not significantly different from the consistently overweight group. We also predicted that weight discrimination would mediate the psychological distress of the formerly overweight group.

Methods

Sample

The primary cohort consisted of 33,604 non-institutionalized participants (M = 48 years, SE = 0.17) in the United States. They responded to predictor and outcome questions in the second wave, which is the most recent one available, of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), sponsored by the United States Census Bureau and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Data were collected from 2004 to 2005 (for survey details, see Ruan et al., 2008). Sample weights made the cohort similar to the 2000 United States Census in age, ethnicity, race, sex, and socioeconomic status. Our mediation analysis required that participants gave weight-discrimination responses. As these latter questions were only asked of participants who reported being overweight at some point in their lives, our analyses included a subset of 20,649 participants (M = 49 years, SE = 0.19).

Measures

We created four predictor-weight groups: formerly overweight (overweight childhood, currently normal weight); consistently normal weight (normal-weight childhood, currently normal weight); consistently overweight (overweight childhood, currently overweight); and subsequently overweight (normal-weight childhood, currently overweight). Childhood weight was assessed with, “When you were growing up, that is, before you were 13 years old, were you overweight?” The reliability and validity of self-reported weight has been demonstrated, and it is not significantly influenced by mental-health status (Heymsfield, Allison, Heshka, & Pierson, 1995; Jeffery et al., 2008; White, Masheb, & Grilo, 2010). Additionally, adulthood recall of early obesity has been found to be valid (Must, Willett, & Dietz, 1993). Current weight was based on whether a body mass index (BMI) indicated the participant was overweight (25 or more) or normal weight (less than 25). Sample sizes were: 818 in the formerly overweight group; 10,692 in the consistently normal-weight group; 3895 in the consistently overweight group; and 18,199 in the subsequently overweight group.

The outcomes, experienced in the past year, consisted of suicide attempts, and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for both any anxiety disorder and any depressive disorder. Anxiety disorders consisted of panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Depressive disorders consisted of major depression and dysthymia. Among our participants, 5823 had any anxiety disorder, 3060 had any depressive disorder, and 116 had attempted suicide. To examine mediation, we combined these outcomes as “psychological distress.”

The covariates, associated with BMI were: age, income, physical health assessed by number of chronic conditions, and sex (Wang & Beydoun, 2007). All covariates were included in all logistic regression models. The mediator of perceived lifetime-weight discrimination was measured with the Experiences of Discrimination scale (Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005).

Results

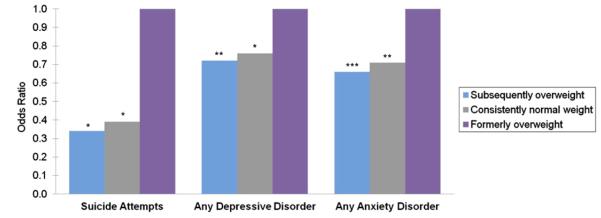

As predicted, the formerly overweight group was significantly more likely than the consistently normal-weight group to have had any anxiety disorder (OR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.15–1.75, p = .002), any depressive disorder (OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.01–1.71; p = .04), and suicide attempts (OR = 2.57, 95% CI = 1.10–6.02, p = .03), in the past year. Also as predicted, the formerly overweight group did not differ significantly from the consistently overweight group in the likelihood for any anxiety disorder (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.89–1.39, p = .34) and for any depressive disorder (OR = 1.03, 95%, CI = 0.79–1.35, p = .83); but the formerly overweight group was significantly more likely than the consistently overweight group to have attempted suicide in the past year (OR = 3.13, 95% CI = 1.04–9.42, p = .04). Additionally, the formerly overweight group was significantly more likely than the subsequently overweight group to have had any anxiety disorder (OR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.25–1.86, p = .0001), any depressive disorder (OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.07–1.80, p = .01), and suicide attempts (OR = 2.96, 95% CI = 1.14–7.66, p = .03), in the past year (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Elevated suicide attempts, any depressive disorders, and any anxiety disorders in the formerly overweight group, compared with the subsequently overweight and consistently normal weight groups during past year. Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .0001. Odds ratios are adjusted for age, sex, income, and number of chronic-physical-health conditions. There were no significant differences between the formerly overweight group and the consistently overweight group with respect to any depressive disorder and any anxiety disorder. However, the formerly overweight group demonstrated significantly elevated odds for suicide attempts, compared with the consistently overweight group.

In accord with our prediction, weight discrimination mediated the greater likelihood of any anxiety disorder, any depressive disorder, and suicide attempts in the formerly overweight group, according to Baron and Kenny’s (1986) mediator criteria. Compared with the consistently normal-weight group, the formerly overweight group experienced: (a) significantly greater psychological distress (OR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.36–2.32, p = .0001); (b) significantly greater weight discrimination (OR = 2.53, 95% CI = 1.67–3.84, p < .0001); and (c) significantly greater psychological distress after adjusting for weight discrimination (OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.29–2.20, p = .0003). The Sobel test was significant (p < .0001) (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The mediation analysis adjusted for all covariates.

The consistently overweight group reported experiencing the most weight discrimination (20.49%), followed by the formerly overweight group (11.69%), and then by the subsequently overweight group (7.41%). The formerly overweight group reported experiencing significantly more weight discrimination than the subsequently overweight group (OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.09–2.25 p = .02) even after adjusting for all covariates. The female participants were significantly more likely to report experiencing weight discrimination (11.8%) than the male participants (6.9%; X2 = 69.39, p < .0001). When sex difference by weight groups was considered, it was found that women were significantly more likely than men to report experiencing weight discrimination if they belonged to the consistently overweight group (X2 = 26.03, p < .0001) or the subsequently overweight group (X2 = 51.55, p < .0001), but a gender difference was not found in the formerly overweight group (X2 = 0.89, p = .35). In moderation analysis, the association of being formerly overweight and greater likelihood of experiencing any anxiety disorder, any depressive disorder, and suicide attempts was consistent for women and men.

Discussion

This study has shown for the first time that formerly overweight individuals, in a nationally representative sample, were susceptible to psychological distress. Specifically, the formerly overweight group was at significantly greater risk of any anxiety disorder, any depressive disorder, and suicide attempts than the consistently normal-weight and subsequently overweight groups; further, the risk of the formerly overweight group for any anxiety disorder and any depressive disorder did not significantly differ from the consistently overweight group. It is striking that the risk of suicide attempts was significantly greater in the formerly overweight group than in the consistently overweight group.

Identifying the causes that underlie the highest prevalence of suicide attempts occurring in the formerly overweight group requires future research. It may be that, for some individuals, becoming formerly overweight carried with it unrealistic expectations of what would be available interpersonally and institutionally when normal weight was achieved; a lack of fulfillment could no longer be attributed to being overweight. Alternatively, or additionally, coping mechanisms that became ingrained and adaptive for overweight individuals may have become maladaptive if they were retained when the individuals reached normal weight.

Perceived weight discrimination partially mediated the greater risk of psychological distress for formerly overweight individuals, even though this discrimination may have been anachronistic: they reported being overweight before age 13. Childhood, as a formative period for self-images, was likely to have provided the early-perceived weight discrimination of these individuals with saliency that extended into adulthood. In turn, the prolonged saliency may have generated a predisposition to perceive weight discrimination when it was not warranted by the reality of everyday life. These possibilities are suggested by our finding that lifetime perceived discrimination was significantly greater for the formerly overweight group than for the subsequently overweight group. The distinctive processing of perceived weight discrimination operated equally among formerly overweight women and men—there was no significant difference between the genders regarding what they reported; in contrast, the consistently and subsequently overweight women reported significantly higher levels of discrimination than the men.

The overall results of this study suggest that losing a self-image shaped by discrimination is a more protracted process than losing weight. Even though others may define individuals as no longer belonging to a stigmatized group, it does not follow that the individuals define themselves as having made the passage. For there is likely to be considerable discontinuity between the objective reality of being normal weight and the lagging subjective reality of being formerly overweight. The resultant psychological challenge is easily underestimated by others, as illustrated by the following example: “Because a change from stigmatized status to normal status is presumably in a desired direction, it is understandable that the change, when it comes, can be sustained psychologically by the individual” (Goffman, 1963, p. 132). Rather, our findings indicate that researchers’ efforts to understand the adverse consequences of being overweight, and clinicians’ efforts to alleviate these consequences, ought to include the period in which the formerly overweight are currently vulnerable to psychological distress.

Acknowledgements

The work for this report was funded by an Investigator Award from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation and grants from the National Institutes of Health R01AG032284 and R01HL089314 to Dr. Levy.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . DSM IV: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. fourth edition American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical consider-ations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Schmalz DL, Young LM, Birch LL. Overweight girls who internalize fat stereotypes report low psychosocial well-being. Obesity. 2008;16(Suppl. 2):S30–S38. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman KE, Reichmann SK, Costanzo PR, Zelli A, Ashmore JA, Musante GJ. Weight stigmatization and ideological beliefs: relation to psychological functioning in obese adults. Obesity Research. 2005;13:907–916. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymsfield SB, Allison DB, Heshka S, Pierson R. Assessment of human body composition. In: Allison D, editor. Handbook of assessment methods for eating behaviors and weight-related problems: Measures, theory, and research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 515–560. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, Finch EA, Linde JA, Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Operskalski BH, et al. Does clinical depression affect the accuracy of self-reported height and weight in obese women? Obesity. 2008;16:473–475. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR. Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Slade MD, Kunkel SR, Kasl SV. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:261–270. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L. On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Must A, Willett WC, Dietz WH. Remote recall of childhood height, weight, and body build by elderly subjects. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1993;138:56–64. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, et al. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ, Burt V. Obesity and the body image: II. Age at onset of disturbances in the body image. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1967;123:1443–1447. doi: 10.1176/ajp.123.11.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States—gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiological Review. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Brownell KD, Wadden TA. The influence of the stigma of obesity on overweight individuals. International Journal of Obesity. 2004;28:1333–1337. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MA, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Accuracy of self-reported weight and height in binge eating disorder: misreport is not related to psychological factors. Obesity. 2010;18:1266–1269. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]