Summary

Phage display has identified the dodecapeptide YHWYGYTPQNVI (GE11) as a ligand that binds to the EGFR but does not activate the receptor. Here we compare the EGFR binding affinities of GE11, EGF and their polyethyleneimine-polyethyleneglycol (PEI-PEG) conjugates. We find that although GE11 by itself does not exhibit measurable affinity to the EGFR, tethering it to PEI-PEG increases its affinity markedly, and complex formation with PolyIC further enhances the affinity to the sub-micromolar range. PolyIC/PPGE11 has a similar strong antitumor effect against EGFR over-expressing tumors in vitro and in vivo, as PolyIC/Polyethyleneimine-polyetheleneglycol-EGF (PolyIC/PP-EGF). Absence of EGFR activation, as previously shown by us (see text) and easier production of GE11 and GE11 conjugates, confer PolyIC/PPGE11 a significant advantage over similar EGF-based polyplexes as a potential therapy of EGFR over-expressing tumors.

Keywords: EGFR, GE11, PolyIC

INTRODUCTION

In recent years we have focused our efforts to target the immune system to tumors, attempting to avoid systemic immunotoxic effects (1). We have chosen PolyInosine/Cytosine (PolyIC) bound to ligand guided chemical vectors that home to receptor proteins, which are over-expressed on cancer cells and are induced to internalize upon ligand binding. Following internalization, PolyIC activates multiple cell killing mechanisms and induces strong bystander effects, leading to killing of both targeted and non-targeted tumor cells (2,3). The bystander effects are localized to the tumor and are much stronger than antibody dependent cell toxicity (ADCC) evoked by anti tumor antibodies. We have utilized this approach successfully with the EGFR, (2,3) which is over-expressed in a variety of solid tumors, making it an attractive target for delivering different anticancer drugs. Several EGFR targeted macromolecular carriers, like liposomes loaded with chemotherapeutics, (4) nanocrystals (5) and also nucleic acids (6), (3) have been successfully delivered into EGFR-over-expressing cells both in vitro and in experimental animal models. EGF protein from natural sources or recombinant production can be easily covalently coupled to gene carriers. Its high binding affinity to EGFR leads to highly specific cell binding and subsequent internalization (7), and allows systemic targeting of EGFR-over-expressing tumors. Binding and internalization of EGF, however, generally results in EGFR activation, which may be a disadvantage in the case of antitumoral therapies. Hence, alternatives for efficient targeting, in the absence of EGFR activation, are desired. In addition, the use of recombinant EGF for targeting chemical gene delivery vectors can become expensive when moving towards clinical development of such synthetic vectors.

The dodecapeptide YHWYGYTPQNVI (GE11) was identified as an EGFR ligand that binds to the receptor, internalizes but does not activate the EGFR (8). Conjugation of GE11 to polyethyleneimine-polyethyleneglycol (PEI-PEG-GE11, PPGE11) enabled the targeting of EGFR over-expressing tumors in vitro and in vivo (9,10). We have recently shown that local and systemic application of EGFR-targeted poly Inosine/Cytosine (PolyIC) by PEI-PEG-EGF (PP-EGF) eradicates several pre-established EGFR-over-expressing tumor models (2,3). Here we compare the efficacies of PPGE11 and PP-EGF in targeted PolyIC treatment of EGFR over-expressing cancers, and demonstrate that in vitro and in vivo efficacies of both vectors are comparable.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General

PP-EGF and PPGE11 were synthesized as described previously (9,11). Polyinosine-cytosine (PolyIC) was obtained from Calbichem (Rehovot, Israel), and dissolved in diethylpropylcarbonate-treated double-distilled water.

For in vitro radioactive binding and displacement studies, GE11 (YHWYGYTPQNVI, MW=1541) was custom-synthesized by GL biochem LTD (Shanghai), and its structure and purity were confirmed by HPLC and MS. Recombinant human EGF (hEGF, Peprotech Asia, Rehovot, Israel) and [125I]-EGF (PerkinElmer, MA, USA; specific activity ~ 60 TBq/ mmol) were used as recommended by the manufacturers.

Female nude mice (NUDE-HSD: Athymic Nude-NU mice) aging 3–4 weeks were obtained from Harlan, Rehovot. All animal experiments were performed according to the Hebrew University Ethical Committee regulations.

Cell Culture

EGFR over-expressing A431 human epidermoid vulval carcinoma (12), MDA-MB-468 human breast carcinoma, U87MG human glioma and its EGFR-over-expressing subline U87MG.wtEGFR (13) cell lines, as well as the EGFR-negative U138MG human glioma cell line were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Biological Industries, Beit Ha’emek, Israel) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 104 U/ L Penicillin and 10 mg/ L streptomycin (Biological Industries) at 37°C in 5% CO2. U87MG.wtEGFR cells were also supplemented with geneticin sulphate (G418, GIBCO, UK) at a final geneticin concentration of 500 µg/ mL. MCF7 cells were grown in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI, Biological Industries) supplemented with 10% FBS, 104 U/ L penicillin and 10 mg/ L streptomycin (Biological Industries) at 37°C in 5% CO2. MDA-MB-231 cells were grown in Leibovitz L-15 medium (Biological Industries) supplemented with 10% FBS, 104 U/ L Penicillin and 10 mg/ L streptomycin at 37°C.

Radiochemistry

The radiochemical synthesis of [124I]-GE11 has been recently described (14).

Binding Studies

Measurement of EGFR Content (Bmax) in A431 Cells using [125I]-EGF or [124I]-GE11

A431 cells were suspended in cold PBS/ 1% BSA, and plated in 96-well MultiScreen® filter plates (#MAHVN4510, Millipore, Ireland) at a concentration of 5000 cells/ 180 µL/ well. Following 30-min incubation over ice, the medium was aspirated using a MultiScreenHTS Vacuum Manifold (Millipore), and cells were supplemented with either 190 µL PBS/ 0.1% BSA or 190 µL PBS/ 0.1% BSA containing hEGF (final concentration: 1.5 µM/ well) for measurement of total binding and non-specific binding (NSB), respectively. [125I]-EGF was then added to the wells at increasing concentrations (0 – 3000 picoM/ 0.1 µCi/ 10 µL/ well), and the cells were incubated with the radiolabeled peptide for 4 h at 4°C under gentle shake. Subsequently, the medium was aspirated, wells were washed (×5) using ice-cold PBS/ 0.1% BSA (250 µL/ well), and the filter plate was left under vacuum for complete drying. For visualization and quantification of [125I]-EGF binding, the MultiScreen plate was exposed to a phosphor imager plate (BAS-IP MS 2040 Fuji Photo Film Co., LTD) along with a corresponding calibration curve, for converting pixels into absolute concentrations. The plate was scanned with an Image Reader Bas – 1000 V1.8 scanner, and densitometry was carried out using TINA 2.10 g software.

Measurement of Bmax using [124I]-GE11 was carried out in a similar manner to the aforementioned description, except A431 cells were added with [124I]-GE11 (0 – 3000 picoM/ 0.1 – 0.15 µCi/ 10 µL/ well) rather than with [125I]-EGF. Each experiment was repeated twice using triplicate samples. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism, version 5.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Displacement of Bound [125I]-EGF in A431 Cells

The relative potencies of EGF, GE11 and their corresponding PEI-PEG polyplexes were compared using displacement studies of [125I]-EGF in A431 cells. To this end, cells were suspended in PBS/ 1% BSA, plated in 96-well MultiScreen® filter plates (Millipore) (5000 cells/ 180 µL/ well), and incubated over ice for 30 min with gentle shake. Subsequently, the medium was aspirated, replaced with cold PBS/ 0.1% BSA (180 µL/ well), and increasing concentrations of each non-labeled peptide ligand/ polyplex were added into the wells (10 µL/ well). Finally, the cells were supplemented with [125I]-EGF in PBS/ 0.1% BSA (0.05 µCi/ 500 fmol/ 10 µL/ well), and incubated with the radiolabeled peptide for 4 h over ice under gentle shake. At the end of incubation, the medium was aspirated, wells were washed (×5) using ice-cold PBS/ 0.1% BSA (250 µL/ well), and the filter plate was left under vacuum for complete drying. For visualization and quantification of [125I]-EGF binding, the MultiScreen plate was exposed to a phosphor imager plate (BAS-IP MS 2040 Fuji Photo Film Co., LTD) along with a corresponding calibration curve, for converting pixels into absolute concentrations. The plate was scanned with an Image Reader Bas – 1000 V1.8 scanner, and densitometry was carried out using TINA 2.10 g software. Calculations of median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of each tested ligand were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 5.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Treatment of Subcutaneous A431 Xenografts

Two-million A431 cells were dissolved in 200 µL of PBS and injected subcutaneously into the right flank of immune compromised female athymic nude mice. The volume of growing tumors was calculated as follows: V=LW2/2 (L = length, W = width). When the tumors reached an average volume of 100 mm3, mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 7 per group), and the treatment was initiated. PolyIC was formulated with either PP-EGF or PPGE11 at w/ w ratio of 0.78 (standard) or 1.04 (higher ratio). These correlate with N/ P ratios (molar ratio of nitrogen in LPEI to phosphate in PolyIC) of 6 and 8, respectively. The complexes (25 µg/ mouse of PolyIC, dissolved in 250 µL of HBG buffer) (3) were delivered by intravenous injection every 48 h for 12 days.

Treatment of Intracranial U87MGwtEGFR Tumors

Two similar experiments were performed to analyze efficacy of PolyIC/PP-EGF (1st experiment) and of PolyIC/PPGE11 (2nd experiment). In each experiment, 10,000 U87MG.wtEGFR cells/ mouse were injected intracranially in 5 µL of PBS at a rate of 1 µL/ min into Nude mice. Fifteen days later, mice were randomly divided into four groups, (n = 5 per group), and the treatment was initiated. PolyIC (1 µg/ mouse) was formulated with 0.78 (standard, N/ P = 6) or 1.04 (high ratio, N/ P = 8) µg of PP-EGF or PPGE11 in total 10 µL HBG buffer. Each complex was injected intracranially 3 times, with 48 h intervals, at 10 µL/ min rate. Survival of the animals was then analyzed as described previously (3).

RESULTS

Quantification of Binding Parameters in A431 Cells using [125I]-EGF and [124I]-GE11

A431 cells over-expressing EGFR (12) were used for the binding experiments. Measurement of EGFR content in A431 cells was carried out by adding increasing concentrations of [125I]-EGF (0 – 3000 picoM) to the cells. In the assay plate, one set of cells was incubated with the radiolabeled protein, representing the total binding, whereas a parallel set of cells (NSB) was also added with ~500-fold excess of non-labeled EGF (1.5 µM), to measure non specific binding (NSB). The specific binding (SB) curve was obtained by subtracting the NSB values from corresponding total binding values at each EGF concentration. A representative curve is illustrated in Figure 1, revealing specific binding of [125I]-EGF to its receptor in A431 cells. Calculation of binding parameters from two sets of experiments yielded a Bmax value of 3.34×106 ± 5.7×105 receptors per A431 cell, and a Kd of 0.7 ± 0.4 nM.

Figure 1.

Binding of [125I]-EGF in A431 cells. A431 cells were incubated with [125I]-EGF (0 – 3000 pM, 4°C, 4 h). To measure non-specific binding (NSB), a parallel set of cells was incubated with an excess of unlabeled EGF (1.5 µM). The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5, yielding a Bmax value of 2.77×106 EGFRs/ cell and a Kd value of ~1 nM.

To investigate the specific binding of GE11 to the EGFR, the experiment was repeated under similar conditions, except [125I]-EGF was replaced with [124I]-GE11 as the radiolabeled ligand. Furthermore, two different sets of NSB were examined, using an excess of either unlabeled EGF (Fig. 2 A) or unlabeled GE11 (Fig. 2 B) as displacers. The data presented in Figure 2 indicate that both experimental conditions could yield a typical SB curve; however, the calculated Bmax values were significantly lower than the one calculated using [125I]-EGF, and the extent of NSB was pronounced, exceeding that of the SB. These results differ from those reported by Li et al. (8) who reported that GE11, as a free ligand, possessed high affinity to the EGFR.

Figure 2.

Binding of [124I]-GE11 in A431 cells. A431 cells were incubated with [124I]-GE11 (0 – 3000 pM, 4°C, 4 h). To measure non-specific binding (NSB), two additional sets of cells were incubated with an excess of unlabeled EGF (A) or unlabeled GE11 (B). Calculated Bmax values indicated approximately 340,000 – 450,000 EGFR/ cell.

Displacement of Bound [125I]-EGF by Unlabeled EGF, GE11 and their Corresponding Polyplexes

The potency of GE11 in displacing bound [125I]-EGF from its receptor was evaluated in A431 cells, and compared to that of unlabeled EGF. The results presented in Table 1 indicate that EGF could inhibit [125I]-EGF binding, having an IC50 value of 5.1 ± 0.9 nM, whereas no significant inhibition was attained with GE11 at concentrations up to 1 mM. Similar results were obtained using U87MGwtEGFR cells, wherein unlabeled EGF had an IC50 value of 5.5 ± 4.2 nM, whereas no inhibition of [125I]-EGF binding could be observed at concentrations up to 1 mM of GE11 (data not shown). These results confirm that GE11, as a free ligand, exhibits negligible affinity to the EGFR. Previous reports however, have demonstrated binding of GE11- and EGF-linked targeted liposomes to EGFR-expressing cells in vitro (15), as well as effective and specific gene delivery into EGFR expressing cells, both in vitro and in vivo, using PPGE11 (9,10,16). These results prompted us to further investigate the potencies of tethered GE11 and EGF in inhibiting the binding of [125I]-EGF, when tethered to PEI-PEG. Indeed, and as indicated in Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1, PPGE11 was a much more potent EGFR binder as compared to GE11, possessing an IC50 value of 1900 ± 432 nM, where complexation of PolyIC to PPGE11, generating a polyplex, further enhanced its potency in more than 10-fold (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). A similar effect was observed with the PolyIC/PP-EGF polyplex (Table 1), yet complexation of polyIC to the control conjugate, PPCys, had no effect (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1. Affinities of GE11, EGF and their conjugates to the EGFR.

Inhibition of [125I]-EGF binding in A431 cells by EGF, GE11 and their corresponding polyplexes, PP-EGF, PPGE11, PolyIC/PP-EGF and PolyIC/PPGE11. PPCys and PolyIC/PPCys were employed as controls. A431 cells were incubated with [125I]-EGF (2500 picoM, 4°C, 4 h) and with increasing concentrations of each non-labeled peptide ligand/ polyplex. Following aspiration of the medium and five subsequent washes, the filter plate was exposed to a phosphor imager plate for visualization and quantification of [125I]-EGF binding.

| Unlabeled Peptide Ligand | Tested Concentrations | IC50 [nM]a |

|---|---|---|

| EGF | 0 – 500 nM | 5.1 ± 0.9 (n=12) |

| GE11 | 0 – 1 mM | No inhibition (n=3) |

| PP-EGF b | 0 – 500 nM | 6.9 ± 2.0 (n=2) |

| PPGE11b | 0 – 2.5 µM | 1900 ± 432 (n=3) |

| PPCysb | 0 – 3.5 µM | No inhibition (n=4) |

| PolyIC/PP-EGF b | 0 – 500 nM | << 1 (n=2) |

| PolyIC/PPGE11b | 0 – 600 nM | ~200 (n=2) |

| PolyIC/PPCysb | 0 – 650 nM | No inhibition (n=2) |

Results are presented as mean ± SEM

Concentrations are indicated as EGF/ GE11 or Cys equivalents

In Vitro Tumor Cell Growth Inhibition by PolyIC/PPGE11

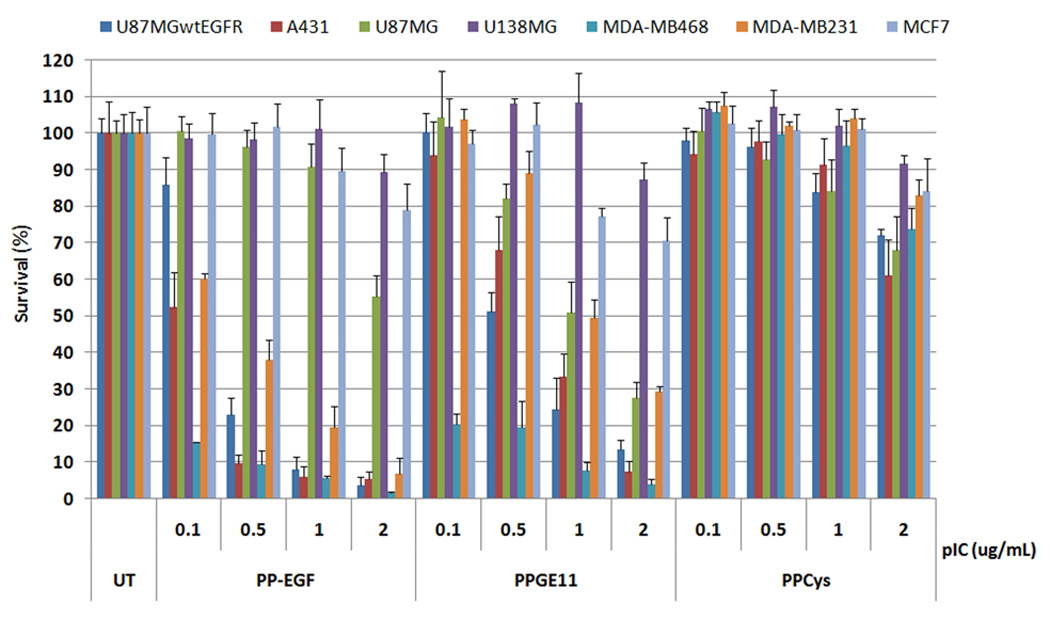

To compare the potency of PolyIC/PPGE11 to that of PolyIC/PP-EGF in tissue culture, seven cell lines that express different levels of EGFR were employed. PolyIC/PPCys was used as a control for non-specific PEI mediated transfection. As illustrated in Figure 3, the potencies of PolyIC/PP-EGF and PolyIC/PPGE11 were generally on a par, with both polyplexes demonstrating greater potencies towards EGFR-rich cells, (i.e.: U87MG.wtEGFR, MDA-MB-468 and A431) as compared to the other cells, which express lower receptor-levels. In contrast, PolyIC/PPCys did not induce significant cell killing in any of the examined cells.

Figure 3.

In vitro comparison of PolyIC/PP-EGF and PolyIC/PPGE11. U138MG (3000 cells) and 4000 cells of each other indicated cell line were seeded into 96 well plates, and grown overnight. Cells were then transfected with PolyIC, formulated with the indicated conjugate, as described (3). Survival of the cells was analyzed by Methylene blue assay 48 h after transfection. U138MG cells do not express EGFR (21); MCF7 express 0.8 – 5×103 EGFRs/ cell. MDA-MB-231 (MDA231): 3 – 7×105; MDA-MB-468 (MDA468): 2×106 (22); U87MG: 1×105; U87MG.wtEGFR: 1×106 (23); and A431: 2 – 3×106 EGFRs/ cell (24). The experiment was repeated 3 times with representative shown.

In Vivo Efficacy of PolyIC/PPGE11

The in-vivo anti-tumor activity of PolyIC/PPGE11 was examined, and compared to that of PolyIC/PP-EGF, using two animal models, namely A431 subcutaneous xenografts and an intracranial GBM model (Fig. 4). The systemic efficacies of both complexes in inhibiting A431 subcutaneous xenografts tumor growth are presented in Figure 4A, indicating that the inhibitory potencies of both polyplexes were comparable. Increasing the N/P ratio for PEI/PolyIC complexation appeared to increase slightly, yet significantly, the inhibitory potencies of both complexes. We did not detect any visible signs of toxicity during this study. More extensive and detailed toxicity studies, such as liver and other organs toxicity, will be performed as part of preclinical preparations.

Figure 4.

In vivo comparison of PolyIC/PP-EGF and PolyIC/PPGE11. PolyIC conjugates were used for treating (A) subcutaneous A431 xenografts and (B, C) intracranial U87MG tumors. Tumors were established and treated as described under materials and methods. (B, C left panels Survival plots and (B, C right panels) average survival period and percentage of increase in survival, following each treatment, with respect to untreated (UT) mice.

The in vivo efficacy of complexes was also compared using an intracranial U87MG.wtEGFR orthotopic model (Fig. 4 B, C), in which complexes were injected intratumorally 15 days after implantation of the cells. PolyIC/PP-EGF was about 20% more efficient in prolonging survival of the treated mice. Thus, PolyIC/PP-EGF and PolyIC/PPGE11 treatments had prolonged survival by 107% and 86%, respectively, with respect to untreated controls. As was previously demonstrated (3), significantly higher doses of the complex could be injected that should lead to even stronger effect or complete elimination of the tumor. Still, the lower doses used in the current study were designed to avoid complete cure of the mice and consequently, more accurate comparison of the two conjugates.

DISCUSSION

Non-viral gene therapy has the advantage over viral therapies with its ability to target specific cells, being less immunogenic and non-integrating into the host genome. EGF has been intensively used for various EGFR-targeted gene delivery approaches, using both viral and nonviral vectors (17), (6), (18), (19). EGF binding to EGFR activates the kinase moiety of the receptor, and leads to autophosphorylation and downstream signaling (20), resulting in proliferation, differentiation, enhanced cell migration and adhesion or inhibition of apoptosis. Consequently, using EGF for tumor targeting has significant disadvantage in the case of antitumoral therapies. In contrast, the GE11 peptide sequence identified by the phage display technique (8) allows highly efficient gene delivery to a broad range of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo, and without EGFR activation (9,10).

In vitro radioactive binding studies using [125I]-EGF and [124I]-GE11 indicated that contrary to [125I]-EGF, radiolabeled GE11 had significant levels of non-specific binding, and could not measure accurately EGFR content in cells (Figs 1, 2). In [125I]-EGF displacement experiments, GE11 could not displace bound [125I]-EGF at concentrations of up to 1 milimolar, whereas the corresponding value for EGF was approximately 5 nanomolar (Table 1). Thus, EGF had a several orders of magnitude higher EGFR-binding affinity/inhibitory potency compared to GE11, as indicated by radioactive binding and displacement studies. Tethering PEI-PEG to GE11 increased its affinity/ potency as compared to the native ligand, whereas no significant effect was observed following PEI-PEG conjugation to EGF. Finally, complexation with PolyIC enhanced potencies of both PP-EGF and PPGE11 by approximately 10-fold, with PolyIC/PP-EGF being 2 – 3 orders of magnitude more potent than PolyIC/PPGE11 in vitro (Table 1). Interestingly, our results differ from those reported by Li et al. who reported to have observed ~22 nM affinity of GE11 to the EGFR (8). Clearly, however, when tethered to PEI-PEG, GE11 exhibits measurable affinity that is further enhanced 10-fold when PPGE11 is complexed with PolyIC. Remembering that in the setting of a phage display, GE11 was discovered in a tethered form, our results are actually in line with the basic finding of Li and co-workers (8). Thus, it seems that the conjugate PPGE11 is a useful EGFR binder and can serve as a chemical vector for targeting the EGFR.

Indeed, we illustrate here the high potency of PEI-PEG-GE11 in delivering PolyIC into EGFR over-expressing tumors. We demonstrate strong killing effect of PolyIC/PPGE11 on EGFR over-expressing tumor cells and a strong anti-tumor activity in vivo. These results suggest that PPGE11 can serve as useful vector for PolyIC to induce the eradication of EGFR over-expressing tumors. The absence of EGFR activation and the more facile synthesis, as compared to PP-EGF, should facilitate the development of PolyIC/PPGE11 into the clinic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study were supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NIH), USA 1R01CA125500 - 01A2 and an ERC a grant from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) / ERC grant agreement no. 249898.

Abbreviations

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- PP-EGF

Polyethyleneimine-polyetheleneglycol-EGF

- PPGE11

Polyethyleneimine-polyetheleneglycol-GE11

- PolyIC

PolyInosine/Cytosine

References

- 1.Levitzki A. Frontiers in Oncology. 2011 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shir A, Ogris M, Roedl W, Wagner E, Levitzki A. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1033–1043. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shir A, Ogris M, Wagner E, Levitzki A. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim IY, Kang YS, Lee DS, Park HJ, Choi EK, Oh YK, Son HJ, Kim JS. J Control Release. 2009;140:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diagaradjane P, Orenstein-Cardona JM, Colon-Casasnovas NE, Deorukhkar A, Shentu S, Kuno N, Schwartz DL, Gelovani JG, Krishnan S. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:731–741. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolschek MF, Thallinger C, Kursa M, Rossler V, Allen M, Lichtenberger C, Kircheis R, Lucas T, Willheim M, Reinisch W, Gangl A, Wagner E, Jansen B. Hepatology. 2002;36:1106–1114. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Bruin K, Ruthardt N, von Gersdorff K, Bausinger R, Wagner E, Ogris M, Brauchle C. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2007;15:1297–1305. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Z, Zhao R, Wu X, Sun Y, Yao M, Li J, Xu Y, Gu J. Faseb J. 2005;19:1978–1985. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4058com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klutz K, Willhauck MJ, Dohmen C, Wunderlich N, Knoop K, Zach C, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Gildehaus FJ, Ziegler S, Furst S, Goke B, Wagner E, Ogris M, Spitzweg C. Hum Gene Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schafer A, Pahnke A, Schaffert D, van Weerden WM, de Ridder CM, Rodl W, Vetter A, Spitzweg C, Kraaij R, Wagner E, Ogris M. Hum Gene Ther. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaffert D, Kiss M, Rodl W, Shir A, Levitzki A, Ogris M, Wagner E. Pharm Res. 2011;28:731–741. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldenberg A, Masui H, Divgi C, Kamrath H, Pentlow K, Mendelsohn J. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1989;81:1616–1625. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.21.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang HS, Nagane M, Klingbeil CK, Lin H, Nishikawa R, Ji XD, Huang CM, Gill GN, Wiley HS, Cavenee WK. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:2927–2935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dissoki S, Hagooly A, Elmachily S, Mishani E. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song S, Liu D, Peng J, Sun Y, Li Z, Gu JR, Xu Y. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2008;363:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klutz K, Schaffert D, Willhauck MJ, Grunwald GK, Haase R, Wunderlich N, Zach C, Gildehaus FJ, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Goke B, Wagner E, Ogris M, Spitzweg C. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 19:676–685. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng KW, Pham L, Ye H, Zufferey R, Trono D, Cosset FL, Russell SJ. Gene therapy. 2001;8:1456–1463. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogris M, Walker G, Blessing T, Kircheis R, Wolschek M, Wagner E. J Control Release. 2003;91:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereboeva L, Komarova S, Roth J, Ponnazhagan S, Curiel DT. Gene therapy. 2007;14:627–637. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlessinger J. Cell. 2002;110:669–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu TF, Cohen KA, Ramage JG, Willingham MC, Thorburn AM, Frankel AE. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1834–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moiseeva EP, Heukers R, Manson MM. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:435–445. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han Y, Caday CG, Nanda A, Cavenee WK, Huang HJ. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3859–3861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibuya K, Komaki R, Shintani T, Itasaka S, Ryan A, Jurgensmeier JM, Milas L, Ang K, Herbst RS, O'Reilly MS. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1534–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.