Abstract

Introduction

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine is highly effective in primary prevention of anogenital warts (AGWs). However, there is lack of systematic review in the literature of the epidemiology of AGWs in Sub Saharan Africa (SSA).

Objective

To review the prevalence, incidence and risk factors for AGWs in SSA prior to the introduction of HPV vaccination programs.

Methods

PubMed/MEDLINE, Africa Index Medicus and HINARI websites were searched for peer reviewed English language published medical literature on AGWs from January 1, 1984 to June 30, 2012. Relevant additional references cited in published papers were also evaluated for inclusion. For inclusion, the article had to meet the following criteria (1) original studies with estimated prevalence and/or incidence rates among men and/or women (2) detailed description of the study population (3) clinical or self-reported diagnosis of AGWs (4) HPV genotyping of histologically confirmed AGWs. The final analysis included 40 studies. Data across different studies were synthesized using descriptive statistics for various subgroups of females and males by geographical area. A meta - analysis of relative risk was conducted for studies that had data reported by HIV status.

Results

The prevalence rates of clinical AGWs among sex workers and women with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or at high risk of sexually transmitted infection (STIs) range from 3.3% - 10.7% in East, 2.4% - 14.0% in Central and South, and 3.5% - 10.5% in West African regions. Among pregnant women, the prevalence rates range from 0.4% - 3.0% in East, 0.2% - 7.3% in Central and South and 2.9% in West African regions. Among men, the prevalence rates range from 3.5% - 4.5% in East, 4.8% - 6.0% in Central and South and 4.1% to 7.0% in West African regions. In all regions, the prevalence rates were significantly higher among HIV+ than HIV- women with an overall summary relative risk of 1.62 (95% CI: 143–1.82).

The incidence rates range from 1.1 – 2.7 per 100 person-years among women and 1.4 per 100 person years among men. Incidence rate was higher among HIV+ (3.0 per 100 person years) and uncircumcised men (1.7 per 100 person-years) than circumcised men (1.3 per 100 person-years).

HIV positivity was a risk factor for AGWs among both men and women. Other risk factors in women include presence of abnormal cervical cytology, co-infection with HPV 52, concurrent bacteria vaginoses and genital ulceration. Among men, other risk factors include cigarette smoking and lack of circumcision.

Conclusions

AGWs are common among selected populations particularly HIV infected men and women. However, there is need for population-based studies that will guide policies on effective prevention, treatment and control of AGWs.

Keywords: Anogenital warts, Sub Saharan Africa, HIV, HPV vaccination

Introduction

The epidemiology of AGWs in most of SSA is largely unknown since few studies have been conducted. Studies from high income countries show that the clinical burden has been increasing over the years since approximately 0.5-1.0% of adults below 50 years have AGWs [1-3].

Caused mainly by low-risk HPV type 6 and 11, AGWs affect both men and women [1]. They are highly infectious with about 65% of individuals with an infected partner developing lesions within 3 weeks [4]. The median time between infection and development of lesions is about 11–12 months among men [5,6] and about 5–6 months among women [7]. Rarely, AGWs have been associated with malignant Bushke-Lowenstein malignant tumors [8]. Their occurrence is strongly linked to HIV and weakly associated with cigarette smoking [1,4,5]. At present, the impact of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) remains unclear [5,6].

Except for Rwanda [9], most countries in SSA are yet to introduce or scale up HPV vaccination in national immunization programs. While reduction in disease burden due to HPV 16/18 may not be evident for decades, vaccination with the quadrivalent HPV vaccine should result in immediate measurable reduction in the incidence rate of AGWs. Preliminary results from the Australian national HPV vaccination program shows a significant decline in the number of cases of AGWs among the young vaccinated women and some herd-immunity effect in young unvaccinated heterosexual men [10]. This review was undertaken to assess the prevalence, incidence and risk factors for AGWs before the introduction of HPV vaccination programs in order to provide a basis for future program evaluation in SSA.

Methods

Identification and eligibility of relevant studies

PubMed/MEDLINE, Africa Index Medicus and HINARI websites were searched for peer reviewed English language published medical literature from January 1, 1984 up to June 30, 2012. The following Medical Subject Heading (MESH) and search terms were used alone or in combination “Sub Saharan Africa” AND (“anogenital warts” OR “venereal warts” OR “condylomata acuminata” OR “condylomata”) AND “risk factors”. Relevant additional references cited in published papers were also evaluated for inclusion. For inclusion, articles had to meet the following criteria (1) original studies with clear estimation of prevalence and/or incidence rates among men and/or women (2) detailed description of study population (3) clinical or self-reported diagnosis of AGWs (4) HPV genotyping of histologically confirmed AGWs. Studies focusing exclusively on case reports and commentaries were excluded.

Data extraction

From each article, the following information was extracted: first author, publication journal name and year of publication, country of study population, study sample type (population- or clinic- based), study design, mean or median age with range/inter quartile range, whenever available, sample size, prevalence and/or incidence rate overall and by HIV status, whenever available, risk factors and the overall prevalence of HIV, whenever available. For studies that included populations from different countries, data was extracted separately for each country.

Statistical analysis

Data across different studies were synthesized using descriptive statistics for different subgroups of females and males by geographical areas. A meta- analysis of relative risk was conducted for studies that had data reported by HIV status and results presented in a forest plot. In total, 40 studies (39 hospital - and 1 population-based) are included in this review.

Results

The prevalence and incidence rates of AGWs in diverse female and male hospital-based study populations in East, Central and South, and West African regions is summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3. Overall, there is inter- and intra-region variations in rates depending on the underlying prevalence rate of HIV-1 infection, study population and age group studied. While both young and adult populations were studied, there seems to be no trend or pattern of prevalence rates by age.

Table 1.

Studies reporting prevalence of AGWs in women

|

Author, |

Country | Study design | Study population | Sample size |

Mean or Median age |

Prevalence of AGWs2 n (%) |

Prevalence |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication year | (years, range/IQR1) | of HIV-1 (%) | ||||||

|

East Africa | ||||||||

| Kreiss et al., 1992 [11] |

Kenya |

§Cross-sectional |

Sex workers |

196 |

30.2 (HIV-1+) 31.5 (HIV-1-) |

18/196 (9.2) Overall 15/145 (10.0) HIV-1+ 3/51 (6.0) HIV-1 |

|

|

| Fonck, et al., 2000 [12] |

Kenya |

"EntryTbl_st§Cross-sectional |

Women attending STD3 clinic |

520 |

26 ± 6.8 (14–49) |

31/520 (6 .0) 5/520 (1.0)a |

29.0 |

Prevalence of AGWs 5% (Non pregnant women) 9% (Pregnant women) 6% (One sexual partner) |

| Mayaud et al., 2001 [13] |

Tanzania |

§Cross-sectional |

Pregnant women |

660 |

23.4 ± 5.1 (15–44) |

20/660 (3.0) |

15.0 |

|

| Riedner et al., 2003 [14] |

Tanzania |

§Open cohort |

Female bar workers |

600 |

25.4 |

39/600 (6.5) Overall 39/408 (9.6) HIV + 0/192 (0.0) HIV - |

68.0 |

|

| Namkinga et al., 2005 [15] |

Tanzania |

§Cross-sectional |

Women presenting with complaints of genital infections |

464 |

|

18/464 (3.9) |

22.0 |

|

| Amone-P'Olak, 2005 [16] |

Uganda |

‡Cross-sectional |

Formally abducted teenage girls in Northern Uganda |

123 |

16.2 ± 2.2 (12–18) |

67/123 (54.5)a |

|

|

| Mbizvo et al., 2005 [17] |

Tanzania |

§Cross –sectional |

Women seeking primary health care services |

382 |

26.7 ± 6.0 |

8/382 (2.1) |

11.5 |

|

| Msuya et al., 2006 [18] |

Tanzania |

§Cross-sectional |

Women seeking reproductive health care services |

382 |

24.6 (14–43) |

7/382 (2.0) |

6.9 |

|

| Riedner et al., 2006 [19] |

Tanzania |

§Serial cross-sectional |

Female bar workers |

600 |

25.5 (16–39) |

5.2-10.7 |

67.0 |

|

| Aboud et al., 2008 [20] |

TanzaniaMalawi and Zambia |

§Cross-sectional |

HIV-1 positive pregnant women |

2292 |

(15–49) |

195/2292 (8.5) |

|

Prevalence of AGWs Blantyre – 42/474 (8.9) Lilongwe – 61/748 (8.2) Dar es Salaam – 31/428 (7.2) Lusaka – 61/642 (9.5) |

| Banura et al., 2008a [21] |

Uganda |

Baseline of a prospective cohort study |

Young women attending a clinic for teenagers |

1275 |

20 (12–24) |

97/1275 (7.6) |

8.6 |

|

| Banura et al., 2008b [22] |

Uganda |

§Baseline of a prospective cohort study |

Pregnant women Attending ANC5 |

987 |

19 (14–24) |

61/987 (6.2) |

7.3 |

|

| Urassa et al., 2008 [23] |

Tanzania |

§Cross-sectional |

Youth attending an STI4 clinic |

214 |

20.2 (Females) (13–24) 21.5 (Males) (11–24) |

7/214 (3.3) |

15.3 |

HIV −1 prevalence in Males – 7.5% |

| Grijsen et al., 2008 [24] |

Kenya |

§Baseline of a prospective cohort study |

Women at risk for HIV-infection |

361 |

27 (23–32) |

8/361 (2.4) |

32.0 |

|

| Msuya et al., 2009 [18] |

Tanzania |

§Cross-sectional |

Pregnant women |

2655 |

24.6 (14–43) |

11/2555 (0.4) Overall 2/184 (1.1) HIV + 9/2470 (0.4) HIV - |

6.9 |

|

| Mapingure, et al., 2000 [25] |

Tanzania |

§Cross-sectional |

Pregnant women |

2654 |

24.6 |

34/2654 (1.3) 48/2654 (1.8)b |

6.9 |

|

|

Central and South Africa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Latif et al., 1984 [26] |

Zimbabwe |

§Cross-sectional |

Pregnant women attending STD clinic |

175 |

22.3 |

23/175 (13.7) |

|

|

| Mason et al., 1990 [27] |

Zimbabwe |

§Cross-sectional |

Women attending STD clinic |

100 |

(15–45) |

14/100 (14.0) 1/59 (1.7)a |

|

|

| Kristensen 1990 [28] |

Malawi |

§Cross sectional |

Adult women with symptoms of STIs |

16,218 |

26.8 ± 7.5 |

32/16,218 (0.2) |

62.4 |

|

| Nzila et al., 1991 [29] |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

§Cross-sectional |

Female sex workers |

1233 |

|

30/1233 (2.4) Overall 21/431 (5.0) HIV + 8/802 (1.0) HIV- |

35.0 |

|

| Le Bacq et al., 1993 [30] |

Zimbabwe |

§Cross-sectional |

New STD clinic attendees |

146 |

|

19/146 (13.0) |

69.0 |

|

| Maher et al., 1995 [31] |

Malawi |

§Cross-sectional |

Female patients in general medical care |

61 |

31 (16–65) |

6/61 (9.8) |

|

|

| Taha et al., 1998 [32] |

Malawi |

§Serial cross-sectional surveys |

Pregnant women |

1990 – 6603 HIV + 1502 HIV- 5101 1993 – 2161 HIV + 694 HIV- 1457 1995 – 808 HIV + 808 HIV- 701 |

|

1990 1993 1995 Overall 4.8 3.1 2.5 HIV + 8.3 6.3 2.7 HIV- 2.2 1.7 1.0 |

23.0 (1990) 30.1 (1993) 32.6 (1995) |

|

| Klaskala et al., 2005 [33] |

Zambia |

§Cross-sectional |

Pregnant women |

3160 |

25 ± 5.3 (14–43) |

203/3160 (6.2) |

|

|

| Mbizvo et al., 2005 [17] |

Zimbabwe |

§Cross –sectional |

Women recruited from primary health care centers |

386 |

26.5 ± 6.8 |

13/386 (3.4) |

29.3 |

|

| Kurewa et al., 2010 [34] |

Zimbabwe |

§Cross-sectional |

Pregnant women |

691 |

24.2 ± 5.1 |

48/691 (7.0) 50 /691 (7.3)a |

25.6 |

|

| Mapingure et al., 2010 [26] |

Zimbabwe |

§Cross-sectional |

Pregnant women |

691 |

24.2 ± 5.1 |

50/691 (7.3) 33/691 (4.8)b |

25.6 |

|

| Menendez et al., 2010 [35] |

Mozambique |

§Cross- sectional |

Women attending ANC and FP6 clinics and community |

262 |

(14–61) |

13/262 (5.0) |

12.0 |

Prevalence of HIV-1 21.0% among FP clinic attendees |

|

West Africa | ||||||||

| Oni et al., 1994 [36] |

Nigeria |

§Cross-sectional |

STD clinic attendees |

116 |

|

12/116 (10.5) |

|

|

| Ghys et al., 1995 [37] |

Ivory Cost |

§Cross sectional |

Female sexual workers |

1209 |

|

105/1209 (8.7) Overall 79/567 (14.0) HIV + 26/642 (4.0) HIV - |

80.0 |

|

| Meda et al., 1997 [38] |

Burkina Faso |

§Cross – sectional |

Women attending ANC |

645 |

25.3 ± 2.9 (15–41) |

19/645 (2.9) |

|

|

| Okesola et al., 2000 [39] |

Nigeria |

§Cross-sectional |

Patients attending an STD clinic |

861 |

(17–74) |

68/861 (8.0) |

|

|

| Bakare et al., 2002 [40] |

Nigeria |

§Cross-sectional |

CSWs7 and women without symptoms of STIs |

|

|

6.5 36.4c |

34.3 |

|

| Domfeh et al., 2008 [41] |

Ghana |

§Cross-sectional |

Women attending gynecological clinic |

75 |

33.3 ± 9.2 (19–57) |

4/75 (5.3)a |

|

|

| Sagay et al., 2009 [42] |

Nigeria |

§Cross-sectional |

Female sex workers |

374 |

27.8 ± 6.7 (16–63) |

17/374 (4.5) |

|

Prevalence of AGWs 5/81 (6.1%) Lemon users 12/293 (4.1%) Non Lemon users |

| Jombo et al., 2009 [43] |

Nigeria |

§Cross- sectional |

Patients with genital ulcer disease |

699 |

|

369/699 (52.8) Overall 285/506 (56.4) HIV + 84/193 (43.6) HIV – |

|

Prevalence Males: 13/329 (2.6%) Females: 8/177 (1.6%) |

| Low et al., 2011 [44] | Burkina Faso | §Baseline of Prospective cohort | CSWs and other women with high-risk sexual behaviors | 765 | 28 (15–54) | 27/765 (3.5) Overall 19/273 (7.0) HIV −1 + 8/492 (1.6) HIV - | 34.9 HIV-1 0.7 HIV-1 &2 | No prevalent AGWs among women on HAART |

a self-reported prevalence; b self-reported prevalence for the last 12 months; c self-reported prevalence among commercial sexual workers; 1Inter quartile range; 2Anogenital warts; 3Sexually transmitted disease; 4Sexually transmitted infection; 5Antenatal care; 6Family planning; 7Commercial sexual workers; § hospital-based study; ‡ Teenagers in an institution.

Table 2.

Studies reporting AGWs in men

| Author, year | Country | Study design | Study population |

Sample |

Mean or Median age |

Prevalence of AGWs2 (%) | Prevalence of HIV-1% | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| size | (years, range/IQR1) | |||||||

|

East Africa | ||||||||

| Grijsen et al., 2008 [24] |

Kenya |

§Baseline of a prospective cohort study |

Men at high-risk for HIV infection |

536 |

27 (24–33) |

9/500 (1.8) |

21.0 |

|

| Smith et al., 2010 [45] |

Kenya |

§Baseline of RCT3 on male circumcision |

HIV negative sexually active men |

2168 |

20 (19–28) |

12/2168 (0.6) Overall 10/1089 (0.9) HIV + 2/1079 ( 0.2) HIV- |

|

|

| Tobian et al., 2012 [46] |

Uganda |

†Cross-sectional |

Heterosexual men |

1399 |

15-49 |

23/1399 (1.6)a Overall 16/421 (3.8)a HIV + 7/978 (0.7)a HIV – |

|

|

|

Central and South Africa | ||||||||

| Le Bacq et al., 1993 [31] |

Zimbabwe |

§Cross-sectional |

New STD clinic attendees |

319 |

|

39/319 (12.2) |

61.0 |

|

| Maher et al. 1995 [32] |

Malawi |

§Cross-sectional |

In-patient male patients in general medical care |

62 |

39 (20–90) |

3/62 (4.8) |

|

|

| Machekano et al., 2000 [47] |

Zimbabwe |

§Baseline of prospective cohort study |

Male factory workers who reported symptoms of STDs |

374 |

|

22/374 (6.0) |

20 |

|

| Müller et al., 2010 [48] |

South Africa |

§Cross-sectional |

Heterosexual men attending sexual health services |

214 |

29.8 ± 7.5 |

108/214 (50.5) |

49.5 |

|

|

West Africa | ||||||||

| Okesola et al., 2000 [40] |

Nigeria |

§Cross-sectional |

STD2 clinic attendees |

1,373 |

17-74 |

4.1 |

|

|

| Wade et al., 2005 [49] | Senegal | §Cross sectional | Men who have sex with men | 463 | 18-52 | 13/463 (2.8) | 18.1 | 21.5% Overall 0.5% HIV-2 2 2.9% HIV-1 & HIV- |

a Self-reported prevalence.

1Inter Quartile Range.

2Commercial sexual workers.

3Randomized Controlled Trial.

§hospital-based study.

†Population-based study.

Table 3.

Studies reporting incidence rates of AGWs in men and women

| Author, year | Country | Study design |

Study population |

Sample |

Mean or |

Incidence rate/1002 |

HIV −1 |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| and site | size |

median age |

person-years of |

prevalence% | ||||

| (years, range) | AGWs2 | |||||||

|

East Africa | ||||||||

| Lavreys et al., 1999 [50] |

Kenya |

Prospective cohort |

HIV negative truck drivers in Mombasa |

746 |

26a (17–58) 29b (16–62) |

1.4 overall 1.7 Uncircumcised 1.3 Circumcised |

|

Annual incidence of HIV-1 – 3.0% |

|

West Africa | ||||||||

| Ozumba et al., 1991 [51] |

Nigeria |

Retrospective cohort (1976–85) |

Female STD1 clinic attendees |

45 |

21 ( 5–36) |

2.7 (range:1.6 – 3.6) |

|

AGWs incidence highest among teenagers and students |

| Low et al., 2011 [44] | Burkina Faso | Prospective cohort | Female sex workers and other women at high risk | 765 | 28 (15–54) | 1.1 HIV - | 34.9 | HIV- 1 & HIV-2 prevalence 0.7% |

a uncircumcised men.

b circumcised men.

1Sexually Transmitted Diseases.

2Anogenital warts.

Prevalence rates among women by geographical region

The prevalence rates among women in East, Central and South, and West African regions are summarized in Tables 1. The prevalence rates of clinical AGWs among sex workers and women with STDs or at high risk for other STIs range from 3.3% - 10.7% in East, 2.4% - 14.0% in Central and South, and 3.5% - 10.5% in West African regions. Among pregnant women, the prevalence rates range from 0.4% - 3.0% in East, 0.2% - 7.3% in Central and South and 2.9% (single study) in West African regions.

Prevalence rates of AGWs among men by geographical region

Eight (8) studies (3 East Africa, 2 Central and South Africa, 3 West Africa) reported prevalence rates of AGWs in men (Table 2). The prevalence rate among STD clinic attendees, men who have sex with men, and men with symptoms of STDs in Central and South and West African region range from 4.8% - 12.2% and 2.8% - 4.1%, respectively. The rates among men in the East African region range from 0.6 -1.8 percent.

Prevalence rates by HIV status

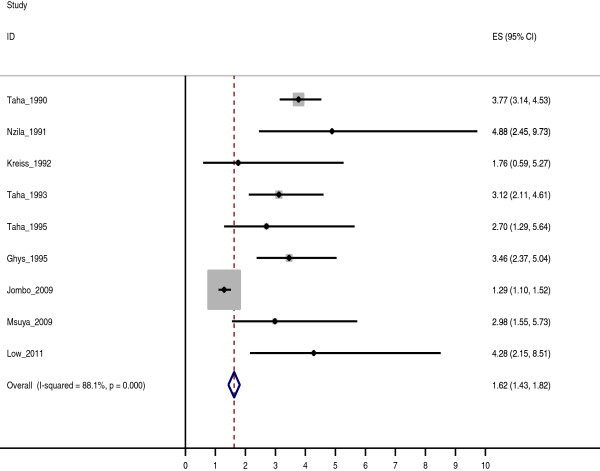

The prevalence rates of AGWs were significantly higher among HIV+ than HIV- women in all regions with an overall summary relative risk of 1.62 (95% CI: 1.43–1.82) (Figure 1). Similarly among men, clinical and self -reported prevalence rates were higher among HIV+ than HIV- men (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Relative Risk of AGWs among women with known HIV sero status.

Incidence rates of AGWs among men and women

Only 3 studies (2 among females and 1 among males) reported incidence rates of AGWs (Table 3). The incidence rates range from 1.1 – 2.7 per 100 person-years among women and 1.4 per 100 person years among men. The incidence rate was higher among uncircumcised (1.7 per 100 person-years) than circumcised men (1.3 per 100 person-years) [44].

HPV 6 and/or 11 in AGWs

Only 3 studies reported the prevalence of HPV 6 and/or 11 in biopsy specimens or swabs taken from AGWs. HPV 11 was detected in 100% vulval-vaginal wart specimens obtained from 9 prepubescent South African girls [52]. HPV 6 and/or 11 was detected in 96.3% of 108 genital swabs taken from heterosexual men with AGWs attending sexual health clinics in South Africa [48]. Among 74 specimens taken from penile warts of HIV+ men in South Africa, HPV 6 was detected in 42.5%, HPV 11 in 32.9% and HPV 6/11 in 68.5% [53].

Risk factors for AGWs

Only 2 studies (one among women and another among men) reported on risk factors for AGWs. Among women, the risk of prevalent AGWs was 5 times higher among HIV-1+ than HIV-1- women and 3 times higher among women who smoked cigarettes than those who did not. Among HIV-1+ women with low CD4+ count (≤ 200 cells/μL), the risk of incident AGWs was elevated 20 fold, and 6fold for women with CD4+ count >200 cells/μL. Other risk factors for incident AGWs in women include detection of HPV 6, concurrent bacterial vaginoses, genital ulceration, presence of abnormal cervical cytology and the detection of cervical HPV 52 [44]. Lack of circumcision and HIV infection were risk factors for AGWs in men [45].

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic review of the epidemiology of AGWs in SSA. The literature suggests that AGWs are prevalent among both men and women populations seeking care in their respective health care systems. The fewer studies among men is not surprising given that women generally have more frequent contact with the health care system than men. Although there is no marked difference between regions, absence of a standardized protocol for diagnosis might have contributed to the observed variations across studies within the same region. Overall, the prevalence rates were higher than those reported from retrospective administrative databases or medical chart reviews in high income countries possibly because of underlying HIV infection in several studies [54].

Consistent with published studies, the risk for AGWs was higher for HIV+ than HIV- men and women [55]. HIV+ women had almost 2 fold risk for HPV infection than HIV-women. While some AGWs may have been a result of new infections, recrudescence of existing HPV infection has been reported among sexually inactive HIV+ women [56]. Impaired CD4+ T-lymphocyte response and other forms of immune dysfunction may be responsible for altering the natural history of HPV infection among HIV infected individuals [57]. The use of highly active anti-retroviral therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of opportunistic malignancies such as Kaposi sarcoma among HIV+ individuals [58], however, their impact on AGWs remains unclear [55,57,59]. On the other hand consistent use of male condoms appears to reduce the risk by 60-70% [60].

Consistent with other studies, HPV 6 and 11 alone or in combination were detected in the few studies that examined HPV genotypes in AGWs specimens albeit small sample sizes. However, the contribution of HPV 11 to the development of AGWs remains unclear [4,7]. The concurrent detection of HPV 52 with HPV 6 was not surprising as co-infection with high risk HPV types has been reported in 20-50% of AGWs [61,62].

In the absence of a clinical test to establish sub clinical HPV 6 and 11 infections, identification of risk factors for acquisition of AGWs independent of other STDs is complex. Consistent with other studies, low CD4+ cell count (≤ 200 cells/μL) and abnormal cervical and anal dysplasias are risk factors for AGWs in HIV+ women and men, respectively [63,64]. Other risk factors for AGWs in women identified in this review included co-infection with HPV 52, and concurrent bacteria vaginoses [65]. In men, anal HPV infection and related dysplasias [39] and lack of circumcision [45] were additional risk factors.

Although AGWs are not life threatening, they cause significant psychological distress and are refractory to conventional therapies, hence the need for prevention [4,66]. The quadrivalent HPV vaccine, correct and consistent condom use and limiting the number of sexual partners are some of the prevention options available to reduce the risk of contracting AGWs.

It is important to note that there are limitations to this study. This review focused only on peer reviewed English language articles published from a few SSA countries, which limits generalization of the findings. Secondly, most studies were conducted in hospital-based study populations, which would favor higher rates than in the general population. Thirdly, the rates should be interpreted with caution because of the differences in study populations and age group studied. While some studies included all adults [31,39], others focused on narrow age ranges of specific populations like young people and pregnant women [23,25] that could have resulted in the observed high rates. Nevertheless, the review provides vital baseline data against which the impact of HPV vaccination could be evaluated in future.

Conclusions

AGWs are common among selected populations particularly HIV+ men and women. However, there is need for population-based studies on AGWs that will guide policies on effective prevention, treatment and control services.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CB conceived the study, searched the literature, drafted the manuscript and produced the final tables FMM, JO, AKB, SK, EKM made substantial contributions to the manuscript and contributed to data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Cecily Banura, Email: cbanura@chdc.mak.ac.ug.

Florence M Mirembe, Email: flormir2002@yahoo.com.

Jackson Orem, Email: JOrem@mucwru.or.ug.

Anthony K Mbonye, Email: akmbonye@yahoo.com.

Simon Kasasa, Email: skasasa@musph.ac.ug.

Edward K Mbidde, Email: ekmbidde@uvri.go.ug.

References

- Lacey C. Therapy for human papillomavirus-related disease. J Clin Virol. 2005;32(Suppl 1):S82–S90. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer SK, Tran T, Sparen P, Tryggvadottir L, Munk C, Dasbach E, Liaw KL, Nygård J, Nygård M. The burden of genital warts: a study of nearly 70,000 women from the general female population in th 4 Nordic countries. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1447–1454. doi: 10.1086/522863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer EV, Demers AA, Elliott L, Lotocki R, Butler JR, Brisson M. Twenty-year trends in the incidence and prevalence of diagnosed anogenital warts in Canada. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(6):380–386. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318198de8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey C, Lowndes C, Shah KV. Chapter 4: Burden and management of non-cancerous HPV-related condition: HPV 6/11. Vaccine. 2006;24S3:S3:/35–S3/41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimi Y, Winer RL, Feng QA, Hughes JP, Lee SK, Stern ME, O'Reilly SF, Koutsky LA. Development of genital warts after incident detection of human papillomavirus infection in young men. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1181–1184. doi: 10.1086/656368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anic GM, Lee GH, Stockwell H, Rollison DE, Wu Y, Papenfuss MR, Villa LL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Gage C, Silva RJ, Baggio ML, Quiterio M, Salmeron J, Abrahamsen M, Giuliano AR. Incidence and human papillomavirus (HPV) type distribution of genital warts in a multinational cohort of men: The HPV in men study. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1886–1892. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland SM, Stenben M, Sings HL, James M, Lu S, Railkar R, Barr E, Haupt RM, Joura EA. Natural history of genital warts: analysis of the placebo arm of 2 randomized phase III trials of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:805–814. doi: 10.1086/597071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AR, Tortolero-Luna G, Ferrer E, Burchell AN, De Sanjose S, Kjaer SK, Munoz N, Schiffman M, Bosch FX. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection in men, cancers other than cervical and benign conditions. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 10):K17–K28. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet. Financing HPV vaccination in developing countries. Lancet. 2011;377(9777):1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60622-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan B, Franklin N, Guy R, Grulich AE, Regan DG, Ali H, Wand H, Fairley CK. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination and trends in genital warts in Australia: analysis of national sentinel surveillance data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:39–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiss J, Kiviat N, Plummer F, Roberts P, Waiyaki P, Ngugi E, Holmes KK. Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Human papillomavirus, and cervical intraepithelial neoplasis in Nairobi prostitutes. Sex Transm Infect. 1992;19(1):54–59. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonck K, Kidula N, Kirui P, Ndinya-Achola J, Bwayo J, Claeys P, Temmerman M. Pattern of sexually transmitted diseases and risk factors among women attending an STD referral clinic in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;7:417–423. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200008000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayaud P, Weiss H, Lacey C, Uledi E, Kopwe LT, Ka-Gina G, Grosskurth H, Hayes RJ, Mabey DC, Lacey CJ. The interrrelation of HIV, cervical human papillomavirus, ans neoplasia among antenatal clinic attenders in Tanzania. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77(4):248–254. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.4.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedner G, Hoffmann O, Nichombe F, Lyamuya EM, Mmbando D, Maboko L, Hay P, Todd J, Hayes R, Hoelscher M, Grosskurth H. Baseline survey of sexually transmitted infections in a cohort of female bar workers in Mbeya region, Tanzania. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:382–387. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.5.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkinga L, Matee M, Kivaisi A, Moshiro C. Prevalence and risk factors for vaginal candidiasis among women seeking primary care for genital infections in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. East Afr Med J. 2005;82(3):138–143. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v82i3.9270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amone-P'Olak. Psychological impact of wae and sexual abuse on adolescent girls in northern Uganda. Intervention. 2005;3(1):33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mbizvo E, Msuya S, Hussain A, Chirenje M, Mbizvo M, Sam N, Stray-Pedersen B. HIV and sexually transmitted infections among women presenting at urban primary health care clinics in two cities of sub-Saharan Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9(1):88–98. doi: 10.2307/3583163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Msuya S, Mbizvo E, Stray-Pedersen B, Sundby J, Sam N, Hussain A. Risk assessment at the primary health care level in Moshi, Tanzania: limits in predicting sexually transmitted infections among women. Cent Afr J Med. 2006;52(9–12):97–104. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v52i9-12.62593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedner G, Rusizoka M, Mmbando D, Maboko L, Grosskurth H, Todd J, Hayes R, Hoelscher M. Decline in sexually transmitted infection prevalence and HIV incidence in female barworkers attending prevention and care services in Mbeya Region. Tanzania. AIDS. 2006;20(4):609–615. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000210616.90954.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboud S, Msamanga G, Read JS, Mwatha A, Chen YQ, Potter D, Potter D, Valentine M, Sharma U, Hoffmann I, Taha TE, Goldenberg RL, Fawzi WW. Genital tract infections amon HIV-infected pregnant women in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19(12):824–832. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banura C, Franceschi S, van Doorn L, Arslan A, Kleter B, Wabwire-Mangen F, Mbidde EK, Quint W, Weiderpass E. Infection with human papillomavirus and HIV among young women in Kampala, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(4):555–562. doi: 10.1086/526792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banura C, Franceschi S, van Doorn L, Arslan A, Kleter B, Wabwire-Mangen F, Mbidde EK, Quint W, Weiderpass E. Prevalence, incidence and clearance of human papillomavirus infection among young primiparous pregnant women in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(9):2180–2187. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urassa W, Moshiro C, Chalamilla G, Mhalu F, Sandstrom E. Risky sexual practices among youth attending a sexually transmitted infection clinic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijsen ML, Graham S, Mwangome M, Githua P, Mutimba S, Wamuyu L, Okuku H, Price MA, McClelland RS, Smith AD, Sanders EJ. Screening for genital and anorectal sexually transmitted infections in HIV prevention trials in Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:364–370. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.028852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapingure MP, Msuya S, Kurewa NE, Mujoma MW, Sam N, Chirenje MZ, Rusakaniko S, Saugstad LF, de Vlas SJ, Stray-Pedersen B. Sexual behavior does not reflect HIV-1 prevalence differences: a comparison study of Zimbabwe and Tanzania. J International AIDS Society. 2010;13(45) doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif A, Bvumbe J, Muongerwa J, Paraiwa E, Chikosi W. Sexually transmitted diseases in pregnant women in Harare, Zimbabwe. Afr j Sex Transm Dis. 1984;1(1):21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason P, Gwanzura L, Latif A, Marowa E. Genital infections in women attending a genito-urinary clinic in Harare, Zimbabwe. Genitourin Med. 1990;66:178–181. doi: 10.1136/sti.66.3.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen J. The prevalence of symptomatic sexually transmitted diseases and human immunodeficiency virus infection in outpatients in Lilongwe, Malawi. Genitourin Med. 1990;66(4):244–246. doi: 10.1136/sti.66.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nzila N, Laga M, Thiam MA, Mayimona K, Edidi B, Van Dyck E, Behets F, Hassig S, Nelson A, Mokwa K. et al. HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases among female prostitutes in Kinshasa. AIDS. 1991;5:715–721. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bacq F, Mason P, Gwanzura L, Robertson V, Latif A. HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases at a rural hospital in Zimbabwe. Genitourin Med. 1993;69:352–356. doi: 10.1136/sti.69.5.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher D, Hoffman I. Prevalence of genital infections in medical inpatients in Blantyre, Malawi. J Infect. 1995;31:77–78. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(95)91674-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha T, Dallabetta GA, Hoover DR, Chiphangwi JD, Mtimavalye LA, Liomba GN, Kumwenda NI, Miotti PG. Trends of HIV-1 and sexually transmitted diseases among pregnant and post-partum women in urban Malawi. AIDS. 1998;12:197–203. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199802000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaskala W, Brayfield BP, Kankasa C, Bhat G, West JT, Mitchell CD, Wood C. Epidemiological Characteristics of Human Herpesvirus-8 Infection in a Large Population of Antenatal Women in Zambia. J Med Virol. 2005;75:93–100. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurewa N, Mapingure M, Munjoma M, Chirenje M, Rusakaniko S, Stray-Pedersen B. The burden and risk factors for sexually transmitted infections and reproductive tract infections among pregnant women in Zimbabwe. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez C, Castellsague X, Renom M, Sacarlal J, Quinto L, Lloveras B, Klaustermeier J, Kornegay JR, Sigauque B, Bosch FX, Alonso PL. Prevalence and risk factors of sexually transmitted infections and cervical neoplasia in women from a rural area of Southern Mozambique. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2010. Published online 2010 July 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oni A, Adu F, Ekweozor C. Isolation of herpes simplex virus from sexually transmitted disease patients in Ibadan, Nigeria. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21(4):187–190. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199407000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghys PD, Diallo OM, Ettiègne-Traoré V, Yeboue KM, Gnaore E, Lorougnon F, Kal K, Van Dyck E, Brattegaard K, Hoyi YM, Whitaker JP, De Cock KM, Greenberg AE, Piot P, Laga M. Genital ulcers associated with human immunodeficiency virus-related immunosuppression in female sex workers in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. J Infect Dis. 1995;172(5):1371–1374. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda N, Sangaré L, Lankoandé S, Sanou P, Campaore PT, Catraye J, Cartoux M, Soudré RB. Pattern of sexually transmitted diseases among pregnant women in Burkina Faso, West Africa: potential for a clinical management based on simple approaches. Genitourin Med. 1997;73:188–193. doi: 10.1136/sti.73.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okesola A, Fawole O. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genital infections in sexually transmitted diseases clinic attendees in Ibadan. West Afr J Med. 2000;19(3):195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakare RA, Oni AA, Umar US, Adewole IF, Shokunbi WA, Fayemiwo SA, Fasina NA. Pattern of sexually transmitted diseases among commercial sex workers (CSWs) in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2002;31(3):243–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domfeh AB, Wiredu EK, Adjei AA, Ayeh-Kumi PFK, Adiku TK, Tet-tey Y, Gyasi RK, Armah HB. Cervical human papillomavirus infection in Accra, Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2008;42(2):71–78. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v42i2.43596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagay AS, Imade GE, Onwuliri V, Egah DZ, Grigg MJ, Musa J, Thacher TD, Adisa JO, Potts M, Short RV. Genital tract abnormalities among female sex workers who douche with lemon/lime juice in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2009;13(1):37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jombo E, Okwori E, Otor G, Odengle E. Patterns of genital ulcer diseases among HIV/AIDS patients in Benue State, North Central Nigeria. Internet J Epidemiol. 2009;7:2. [Google Scholar]

- Low A, Clayton T, Konate I, Nagot N, Ouedraogo A, Huet C, Didelot-Rousseau M-N, Michel S, Van de Perre P, Mayaud P. the Yérélon Cohort Study Group, Genital warts and infection with human immunodeficiency virus in high-risk women in Burkina Faso: a longitudinal study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Moses S, Hudgens MG, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Ndinya-Acholi JO, Snijders P, Meijer JF, C. J. L. M, Bailey RC. Increased risk of HIV acquisition among Kenyan men with human papillomavirus infection. JID. 2010;201(11):1677–1685. doi: 10.1086/652408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobian AA, Grabowski MK, Kigozi G, Gravitt PE, Eaton KP, Serwadda D, Nalugoda F, Wawer MJ, Quinn TC, Gray RH. High-risk human papillomavirus prevalence is associated with HIV infection among heterosexual men in Rakai, Uganda. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;89(2):122–127. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machekano R, Bassett M, Zhou P, Mbizvo M, Latif A, Katzenstein D. Report of sexually transmitted diseases by HIV infected man during follow up: time to target the HIV infected? Sex Transm Inf. 2000;76:186–192. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller EE, Chirwa TF, Lewis DA. Human papillomavirus infection in heterosexual South African men attending sexual health services: associations between HPV and HIV serostatus. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:175–180. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.037598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade AS, Kane CT, Diallo PA, Diop AK, Gueye K, Mboup S, Ndoye I, Lagarde E. HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Senegal. AIDS. 2005;19:2133–2140. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194128.97640.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavreys L, Rakwar J, Thompson M, Jackson D, Mandaliya K, Chohan BH, Bwayo JJ, Ndinya-Ochola JO, Kreiss JK. Effect of circumcision on incidence of HIV-1 and other sexually transmitted diseases: A prospective cohort study of trucking company employees in Kenya. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(2):330–336. doi: 10.1086/314884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozumba B, Megafu U. Pattern of vulval warts at the University of Nigeria teaching hospital, Enugu, Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1991;34:347–352. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(91)90603-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright C, Taylor L, Cooper K. HPV typing of vulvovaginal condylomata in children. S Afr Med J. 1995;85(10 Suppl):1096–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firnhaber C, Sello M, Maskew M, Williams S, Schulze D, Williamson AL, Allan B, Lewis D. Human papillomavirus types in HIV seropositive men with penile warts in Johannsesburg, South Africa. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22(2):107–109. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel H, Wagner M, Singhal P, Kothari S. Systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of genital warts. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg M, Ahdieh LM, Anastos K, Burk R, Cu-Uvin SD, Greenblatt RM, Klein RS, Massad S, Minkoff H, Murderspach L, Palefsky J, Piessens E, Schuman P, Watts H, Shah KV. The impact of HIV infection and immunodeficiency on human papillomavirus type 6 or 11 infection and on genital warts. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:427–435. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickler H, Burk RD, Fazzari M, Burk R, Fazzari M, Anostos K, Minkkoff H, Massad LS, Hall C, Bacon M, Levine AM, Watts DH, Silverberg MJ, Xue X, Schlecht NF, Melnick S, Palefsky JM. Natural history and possible reactivation of human Strickler H et al. Natural history and possible reactivation of human papillomavirus in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:577–586. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massad L, Silverberg M, Springer G, Minkoff H, Hessol N, Palefsky JM, Strickler HD, Levine AM, Sacks HS, Moxley M, Heather WD. Effect of antiretroviral therapy on incidence of genital warts and vulvular neoplasia among women with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasti G, Martellota F, Berretta M, Mena M, Fasan M, Di Perri G. Impact of highly active anti retroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndromme-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;11:2440–2446. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard I, Tassie J, Schmitz V, Mandelbrot L, Kazatchkine M, Orth G. Increased risk of cervical disease among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women with severe immunosuppression and high human papillomavirus load(1) Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:403–409. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(00)00948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhart L, Koutsky L. Do condoms prevent genital HPV infection, external genital warts or cervical neoplasia? Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(11):725–735. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200211000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubin F, Prétet JL, Jacquard AC, Saunier M, Carcopino X, Jaroud F, Pradat P, Soubeyrand B, Leocmach Y, Mougin C, Riethmuller D. EDiTH Study Group. Human papillomavirus genotype distribution in external acuminata condylomata: a Large French National Study (EDITH IV) Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:610–615. doi: 10.1086/590560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepapeliere P, Barraso R, Meijer CJ, Walboomers JM, Wettendorff M, Stanberry LR, Lacey CJ. Randomized controlled trial of an adjuvented human papillomavirus type 6 L2E7 vaccine: infection of external genital warts with multiple HPV types and failure of therapeutic vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:2099–2107. doi: 10.1086/498164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L, Estcourt C, Simpson J, Mindel A. Risk factors for acqusition of genital warts: are condoms protective? Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:312–316. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.5.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscicki A, Hills N, Shiboski S, Powell K, Jay N, Hanson E, Miller S, Clayton L, Farhat S, Broering J, Darragh T, Palefsky J. Risks for incident human papillomavirus infection and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion development in young females. JAMA. 2001;285:2995–3002. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts DH, Fazzari M, Minkoff H, Hillier SL, Sha B, Glesby M, Levine AM, Burk R, Palefsky JM, Moxley M, Ahdieh-Grant L, Strickler HD. Effects of bacterial vaginosis and other genital infections on the natural history of human papillomavirus infection in HIV-1 infected and high-risk HIV-1 uninfected women. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(7):1129–1139. doi: 10.1086/427777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson G, Dahlöf LG, Krantz I. Physical and psychological effects of anogenital warts in female patients. Sex Transm Dis. 1993;20:10–13. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]