Abstract

Sec1/Munc18 proteins facilitate the formation of trans-SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) complexes that mediate fusion of secretory granule (SG) with plasma membrane (PM). The capacity of pancreatic β-cells to exocytose insulin becomes compromised in diabetes. β-Cells express three Munc18 isoforms of which the role of Munc18b is unknown. We found that Munc18b depletion in rat islets disabled SNARE complex formation formed by syntaxin (Syn)-2 and Syn-3. Two-photon imaging analysis revealed in Munc18b-depleted β-cells a 40% reduction in primary exocytosis (SG-PM fusion) and abrogation of almost all sequential SG-SG fusion, together accounting for a 50% reduction in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). In contrast, gain-of-function expression of Munc18b wild-type and, more so, dominant-positive K314L/R315L mutant promoted the assembly of cognate SNARE complexes, which caused potentiation of biphasic GSIS. We found that this was attributed to a more than threefold enhancement of both primary exocytosis and sequential SG-SG fusion, including long-chain fusion (6–8 SGs) not normally (2–3 SG fusion) observed. Thus, Munc18b-mediated exocytosis may be deployed to increase secretory efficiency of SGs in deeper cytosolic layers of β-cells as well as additional primary exocytosis, which may open new avenues of therapy development for diabetes.

Glucose stimulation of islet β-cells triggers an initial robust first-phase glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS), followed by a diminished but sustained second-phase GSIS. In type 2 diabetes, islet insulin secretory capacity cannot meet the increasing insulin demand caused by insulin resistance; β-cells eventually decompensate with loss of first-phase GSIS, and second-phase GSIS becomes defective (1). Although previous studies have identified the molecular circuitry underlying β-cell stimulus-secretion coupling (rev. in 2,3), the precise molecular determinants of the complex steps of insulin secretory granule (SG) exocytosis with plasma membrane (PM), termed primary exocytosis, remain unclear. In mast cells and eosinophils (4,5), rapid and extensive sequential SG-SG fusions account for their high secretory efficiency. Such SG-SG fusions also occur in β-cells but at reduced frequency (1.9–2.6%) and extent (only 2–3 SGs) (6,7), and much less is known about the molecular machinery driving SG-SG fusion.

The membrane fusion machinery requires two key components: SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) and Sec1/Munc18 (SM) proteins (8). The SNARE paradigm dictates that cognate vesicle (v-)SNAREs (vesicle-associated membrane proteins [VAMPs]) and target membrane (t-)SNAREs (syntaxins [Syn] and synaptosome-associated protein of 25kDa [SNAP25]) assemble into complexes that mediate different fusion events. Assembly of distinct SNARE complexes is regulated by cognate SM proteins to ensure subcellular compartmental specificity, and that fusion only occurs in response to cellular needs and demand (3,9). Of three SM proteins, Munc18a has been best studied (9–11), including orchestrating SG docking and priming (12,13), chaperoning and inducing activated conformation of Syn-1A (14–16), and facilitating membrane fusion (17,18). In β-cells, much is known about Munc18a and Syn-1A in mediating insulin exocytosis (19,20). Munc18c and cognate Syn-4 mediate GLUT4 translocation to PM in adipose tissue and muscle and also some aspects of GSIS (3). Relatively little is known about Munc18b, which preferentially binds Syn-2 and Syn-3 (21).

Here, we examined the endogenous function of Munc18b by depleting Munc18b in rat β-cells, which showed that Munc18b accounted for a remarkable 50% of GSIS attributed to almost one-half of primary exocytosis and almost all of sequential SG-SG fusion. Gain-of-function expression of Munc18b-wild type (WT) and Munc18b-K314L/R315L (KR) mutant, the latter facilitating SNARE complex assembly (21), greatly increased these two exocytotic events. Mechanistically, Munc18b activated and induced the formation of distinct Munc18b/Syn-2 and Syn-3 SM/SNARE complexes that mediated the primary exocytosis and SG-SG fusion.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Islet isolation, cell culture, and insulin secretion assays.

Islets from Sprague-Dawley male rats (275–300 g) were isolated by collagenase digestion as previously described (22). Islets and INS-1 (832/13; C. Newgard, Duke University, Durham, NC) were cultured in RPMI medium. Batches of 30 rat islets (or INS-1) were transduced with Munc18b lenti–short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (small interfering RNA [siRNA] for INS-1) or AdMunc18b mutants, loaded in perfusion chambers (~1.3 mL capacity) and perifused at a flow rate of ~1 mL/min (37°C). Stimulation was with glucose in presence or absence of 10 nmol/L glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) plus 150 μmol/L isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX) as indicated. Insulin secreted was measured by RIA (Linco Research, St. Louis, MO). The experiments were approved by the animal care committees of the University of Toronto and University of Tokyo.

Silencing Munc18b expression and adenovirus construction.

Silencing of endogenous Munc18b was by two strategies: siRNAs for INS-1 cells and lenti-shRNAs for islets. For siRNAs, two 64 bp sequences of siRNA duplex targeted to Munc18b were created corresponding to rat Munc18b cDNA (GeneBank access no. AF263346) with sense and antisense sequences and control scrambled sequences shown in Supplementary Table 1. Transfection of INS-1 cells was with Lipofectamine 2000.

For construction of lentiviruses, pLKO-Munc18b-eCFP plasmid was created by modifying the parental pLKO-Munc18b-puro plasmid that we have previously described (15) through replacement of puromycin-resistance gene with eCFP. Knockdown plasmid was cotransfected with psPAX2 and pMDG2 into HEK-293FT cells to generate recombinant lentiviruses, lenti-shRNA/Munc18b-eCFP, and lenti-eCFP (control).

Munc18b mutants tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) in a separate transcription cassette that we previously reported (21) were subcloned into pAdTrack shuttle vector and inserted into pAdeasy-1 backbone. Positive clones screened were used to transfect HEK-293 and viruses released from single plaques and then amplified to high titers.

Two-photon microscopy.

Two-photon extracellular polar tracer (TEP) imaging of exocytosis in islets was performed with an inverted laser-scanning microscope (IX81; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with water-immersion objective lens at ×60 (NA = 1.2) and femtosecond laser (MaiTai; Spectral Physics, Mountain View, CA) as previously described (23). Insulin exocytosis was visualized (6) with 0.3 mmol/L Alexa Fluor Hydrazide (polar fluorescent tracer; Molecular Probes) and normalized to the value per 800 μm2 (per cell). Sequential exocytosis was detected as progression of exocytosis toward the cell interior. Sequential exocytosis occurred far more frequently than predicted from coincidental full fusion of a vesicle followed by another vesicle. Such coincidental events within 1 min and within 0.5 μm laterally and 1 μm axially (T = 2 μm) from initial events can be estimated from frequency of exocytosis per membrane area using Poisson statistics as previously described (6). Given frequencies of exocytosis of 7.7, 14.1, 26.4, and 5.4 events/cell/min in adenovirus(Ad)GFP–, AdMunc18b-WT–, AdMunc18b-KR–, and AdMunc18b-E59K–expressing islets, respectively, the proportions of random simultaneous events are estimated as 0.12–0.51, 0.22–0.92, 0.42–1.73, and 0.086–0.36%, respectively. We previously confirmed with anti-insulin immunostaining that glucose-induced exocytotic responses imaged by our two-photon microscope are from β-cells (7).

Electron and confocal immunofluorescence microscopy.

Electron microscopy (EM) preparation as previously described (23) of 70-nm-thick serial sectioning of AdMunc18b mutant–transduced islets was performed, followed by three-dimensional reconstruction of the serial sections. Three-dimensional modeling, texturing, and rendering work were done with a trial version of Autodesk 3ds max9. As previously described (24), confocal microscopy was performed on an inverted confocal microscope system (DMIRE2; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and deconvolution algorithm applied to images to remove out-of-focus background noise.

Immunoprecipitation.

This was performed as we have previously described (24): 70–75% confluent INS-1 cells were transduced with 1) Munc18b siRNA versus scrambled nonsense siRNA or 2) mutant AdMunc18b mutants versus control AdGFP. INS-1 lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with specific 1.2- to 2.0-μg Syn (-1A, -2, or -3) antibodies and coprecipitated proteins identified with indicated antibodies by Western blotting. All were commercial antibodies except Munc18c (Y. Tamori, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan), VAMP8 (W. Hong, Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore), Syn-4 (J. Pessin, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) and Munc18b (generated by us) (21).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from INS-1 (832/13) cells using TRIzol reagent and purified with RNeasy Kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified RNA was converted to cDNA using SuperScript II RT; real-time PCR was performed using an ABI PRISM 7900HT sequence detection system (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis was by Student t test to compare two variables and by ANOVA and Scheffé tests for multiple comparisons. Significance was P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Munc18b is a major regulator of biphasic GSIS in rat pancreatic islets

Munc18b depletion in β-cells reduces biphasic GSIS.

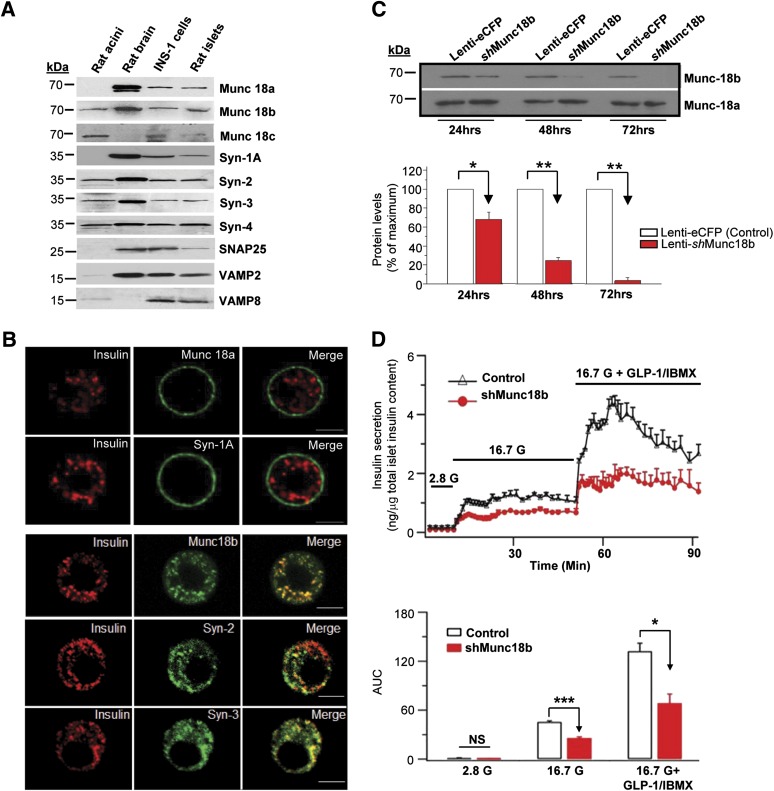

Rat islets and INS-1 contain all three SM proteins, their four cognate Syns (Fig. 1A), SNAP25, VAMP2, and VAMP8. Syn-1A and Munc18a, known to drive primary exocytosis, are more abundant in PM (Fig. 1B). In contrast, Munc18b and cognate Syn-2 and Syn-3 are localized abundantly on insulin SGs, though not exclusively (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Munc18b is a major mediator of GSIS in pancreatic islet β-cells. A: Pancreatic β-cells (rat islets, INS-1) express SM proteins and Syn. Rat pancreatic acini and brain were used as positive and negative controls. B: Immunofluorescence images showing cognate Munc18b and Syn-2 and Syn-3 are abundant in insulin SGs in rat β-cells. Cognate Munc18a and Syn-1A are abundant in the PM. These images are representative of four independent experiments. Scale bars, 10 μm. C: Munc18b depletion in rat islets by lenti-Munc18b shRNA/eCFP vs. eCFP control. Top panel: Representative blots. Bottom panel: Analysis of three experiments, shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. D: Islet perifusion assays of 48 h lenti-shRNA/Munc18b-eCFP (vs. lenti-eCFP [control]) depletion of endogenous Munc18b in rat islets showing reduction of GSIS and GLP-1 (10 nmol/L) plus IBMX (150 µmol/L)-potentiated GSIS, shown as means ± SEM of three independent experiments, and AUC analysis; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. G, glucose.

To examine the endogenous function of Munc18b, we used lenti-shRNAs (coexpressing eCFP) to reduce Munc18b expression in rat islets (24 h, 32%; 48 h, 75%; and 72 h, 97%; all P < 0.05 [Fig. 1C]). Islets transduced for 48 h islets were used in the secretory studies, as 72-h treatment reduced secretory competence. CFP-expressing cells on outermost layers of the islet, which were depleted of Munc18b, were used for two-photon imaging studies.

Physiologic 16.7 mmol/L GSIS was assessed by islet perifusion assay (Fig. 1D), which showed that Munc18b depletion resulted in 44% reduction (area under the curve [AUC] analysis: Munc18b shRNA 25.79 ± 2.49, control 45.54 ± 2.37; P < 0.001). Addition of cAMP-acting GLP-1 (10 nmol/L with 150 μmol/L IBMX) potentiated GSIS to approximately three times (Fig. 1D); Munc18b depletion reduced this by ∼52% (Munc18b shRNA 68.63 ± 19.3, control 132.14 ± 17.15; P < 0.05). IBMX, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that raises intracellular cAMP, was required to be added to GLP-1 to improve consistency. Consistently, Munc18b depletion in INS-1 averaging 86% reduction by either of two siRNAs (siMunc18b nos. 1 and 2) caused a similar ∼40% reduction in 10 mmol/L GSIS (data not shown).

Gain-of-function Munc18b mutant potentiates biphasic GSIS.

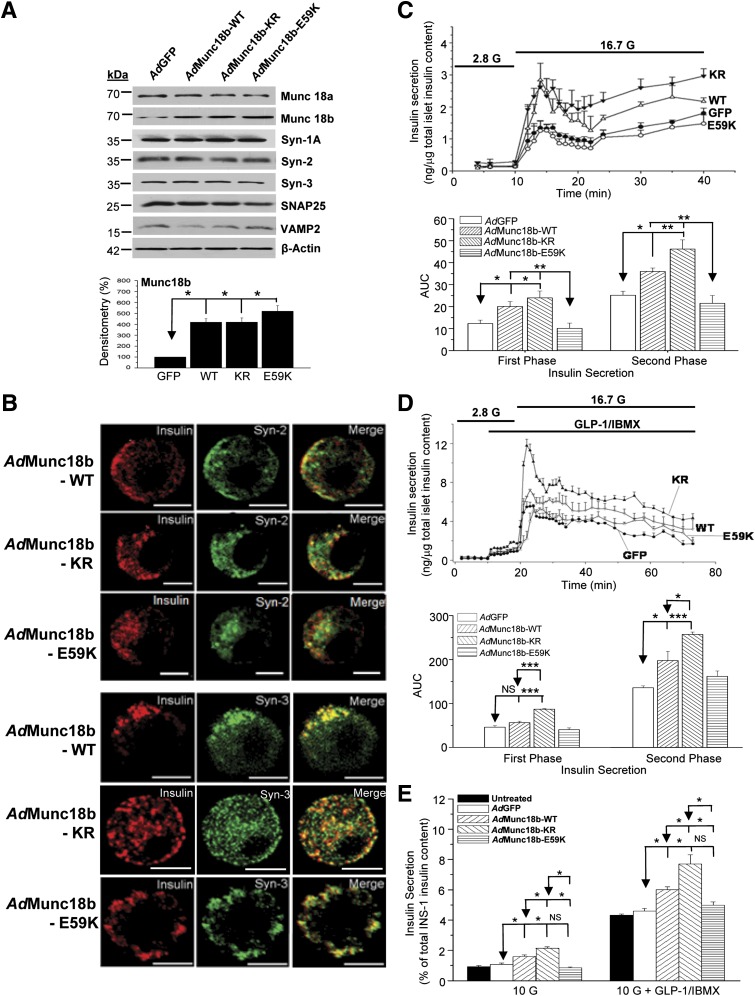

We had previously reported that Munc18b-WT preferentially binds Syn-2 and Syn-3, with Munc18b mutants exhibiting either weaker binding (Munc18b-KR) or no binding (Munc18b-E59K) to these Syns (21). We subcloned these constructs, each coexpressing enhanced GFP to identify transfected cells (for two-photon studies), into adenoviral vectors to transduce islets and INS-1. AdMunc18b mutant expression was ∼4–5 times that of endogenous levels (Fig. 2A); recombinant proteins were expressed in 60–70% of islet cells (GFP visualized by confocal microscopy). Syn-2 and Syn-3 localization to insulin SGs was not affected by any of the three Munc18b proteins (Fig. 2B) (analysis by Pearson correlation; data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Munc18b gain-of-function mutant potentiates GSIS. A: AdMunc18b mutant (-WT, -KR, and -E59K) transduction of rat islets did not influence the expression of SNARE or other SM proteins. Shown are representative of three independent experiments; analysis of Munc18b proteins expression shown in bottom panel. B: Confocal imaging showing AdMunc18b mutants did not influence Syn-2 or Syn-3 targeting to insulin SGs in rat β-cells. Shown are representative of four independent experiments. Scale bars, 10 μm. C and D: Islet perifusion assays showing AdMunc18b mutant–transduced rat islets influencing GSIS (C) and 10 nmol/L GLP-1 plus 150 µmol/L IBMX–potentiated GSIS (D). Data shown are means ± SEM from three to four sets of experiments, with each experiment performed simultaneously in all of the four conditions. Bottom panels show quantification of AUC analysis of first-phase (encompassing 11–22 min) and second-phase (encompassing 22–40 min) GSIS. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA. E: Effects of AdMunc18b mutants on GSIS and 10 nmol/L GLP-1 plus 150 µmol/L IBMX-potentiated GSIS in INS-1 cells. Results shown are means ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in duplicates or triplicates (n = 6–8). *P < 0.05 by ANOVA and Scheffé tests.

We examined the effects of AdMunc18b mutants on biphasic 16.7 mmol/L GSIS (Fig. 2C) and 10 nmol/L GLP-1–potentiated GSIS (Fig. 2D)—the latter approximately four- to fivefold that stimulated by 16.7 mmol/L glucose alone. Munc18b mutant expression in islets did not affect the levels of Syn or cognate SNARE proteins (Fig. 2A). AdMunc18b-WT caused potentiation in first-phase GSIS (encompassing 12–22 min in Fig. 2C) by 63% (20.1 ± 2.2 vs. AdGFP 12.3 ± 1.6; P = 0.03) and second-phase GSIS (encompassing 22–40 min) by 43% (36.0 ± 1.6 vs. AdGFP 25.2 ± 1.8; P = 0.02). AdMunc18b-KR potentiated first-phase GSIS by 95% (24.0 ± 3.1; P = 0.003) and second-phase by 83% (46.2 ± 4.2; P = 0.003)—the latter effect higher than AdMunc18b-WT. AdMunc18b-E59K, intended to induce inhibition, however, did not cause significant reduction (10.1 ± 2.4 vs. 21.5 ± 3.6 for first and second phases, respectively). GLP-1–potentiated GSIS (Fig. 2D) was remarkably similar in pattern to 16.7 mmol/L GSIS, with KR (87.0 ± 1.4 vs. 257.4 ± 5.5) higher than WT (56.6 ± 3.4 vs. 198.1 ± 20.9), which was higher than GFP (46.4 ± 3.4 vs. 136.1 ± 4.3). E59K (40.7 ± 3.9 vs. 162 ± 12.3) and GFP were not significantly different.

Like the islet study, overexpression of AdMunc18b constructs in INS-1 was approximately four times that of untransfected and AdGFP-transfected cells (Supplementary Fig. 1) but with 100% transduction efficiency (all cells are green from coexpressed GFP) required for use in protein-binding studies. As with the islet study, expression of these Munc18b proteins did not affect the cellular levels of Syn-2 or Syn-3, which was confirmed at the mRNA level (Supplementary Fig. 2). There were also no effects on the levels of other Syns (Syn-1A and Syn-4), SNAP25, or SM proteins (Munc18a and Munc18c) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Effects of these Munc18b proteins on INS-1 GSIS (Fig. 2E) were similar to the islet results. Basal insulin release was not affected by AdMunc18b mutants. GSIS (10 mmol/L; determined as stimulated minus basal values) was potentiated by AdMunc18b-KR expression by 98% (2.14 ± 0.09% vs. AdGFP 1.08 ± 0.80%; P < 0.05) and AdMunc18b-WT expression by 48% (1.60 ± 0.11%; P < 0.05), which was lower than AdMunc18b-KR (P = 0.007). AdMunc18b-E59K had no significant effect (0.86 ± 0.05%). GLP-1–potentiated GSIS (10 nmol/L) (Fig. 2E) to approximately four times 10 mmol/L GSIS alone had a trend similar to that of as GSIS alone, wherein AdMunc18b-KR (7.71 ± 0.59%) and AdMunc18b-WT (5.99 ± 0.19%) stimulated secretion by 68 and 30%, respectively, over AdGFP (4.60 ± 0.16; P < 0.05), with AdMunc18b-KR inducing higher secretion than AdMunc18b-WT (P = 0.012); AdMunc18b-E59K (4.98 ± 0.22%) did not cause significant change compared with AdGFP. Thus, Munc18b KD and mutants affected GSIS in INS-1 cells similarly as in β-cells.

Munc18b controls the formation of distinct SM-activated SNARE complexes

Munc18b depletion reduces formation of distinct SM-activated SNARE complexes.

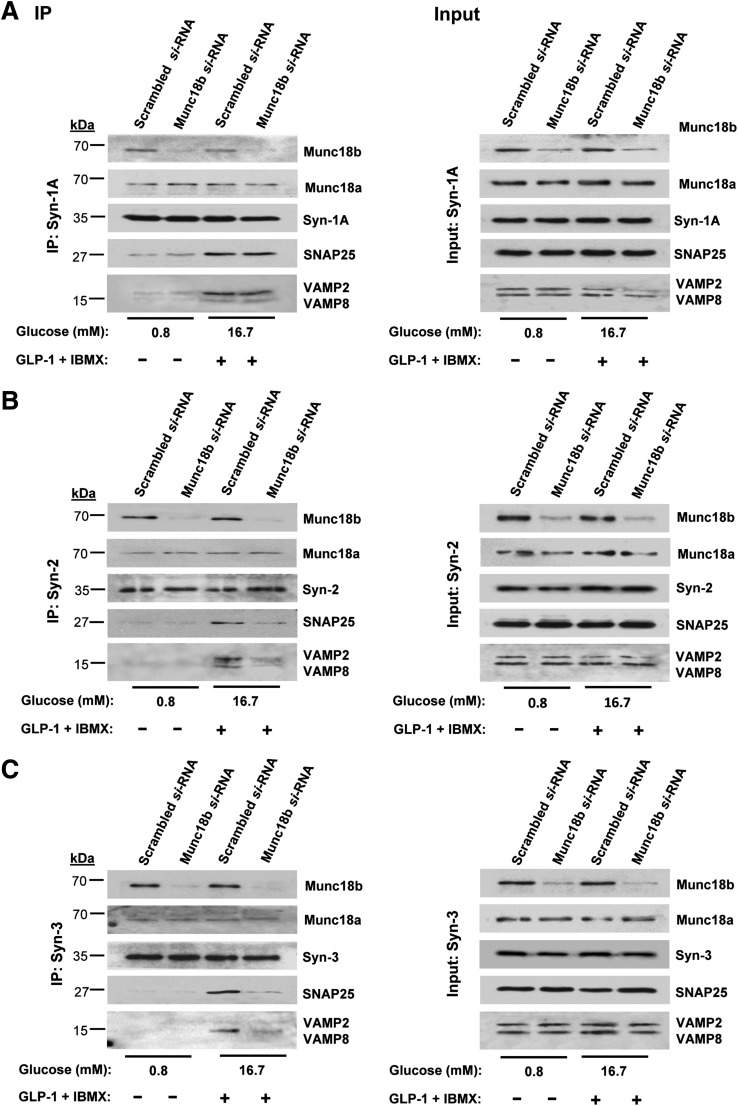

INS-1 cell line was used as a surrogate for β-cells to provide an abundance of protein required for protein-binding studies. We conducted coimmunoprecipitation experiments with antibodies to Syn-1A, Syn-2, and Syn-3 on scrambled (control) and Munc18b-siRNA–treated INS-1 cells, performed at nonstimulatory (0.8 mmol/L glucose) and maximal stimulatory conditions (preincubation with GLP-1 plus IBMX followed by 16.7 mmol/L glucose [Fig. 3, left panels, coimmunoprecipitations; right panels, total lysate input controls; analysis in Supplementary Fig. 3]).

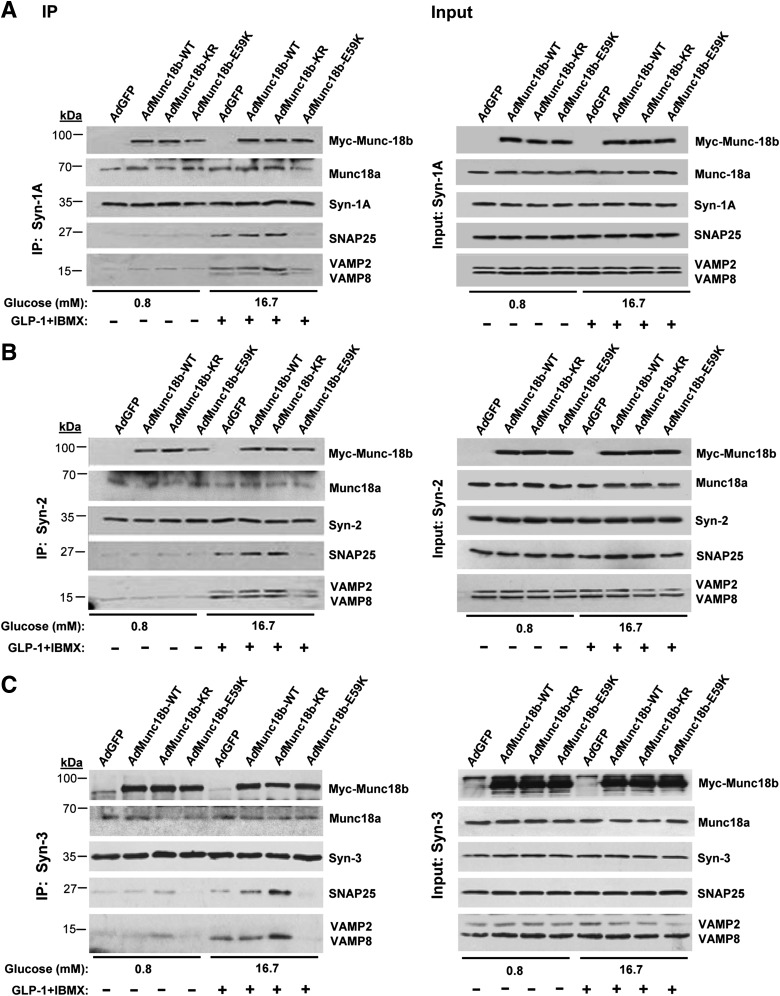

FIG. 3.

Munc18b depletion in INS-1 cells disrupts SM-activated SNARE complex formation. INS-1 cells were transduced with Munc18b siRNA or control scrambled RNA and then kept at basal condition (0.8 mmol/L glucose) or simulated with 16.7 mmol/L glucose plus 10 nmol/L GLP-1 with IBMX (150 μmol/L) and then subjected to coimmunoprecipitation (left panel) with antibodies against Syn-1A (A), Syn-2 (B), or Syn-3 (C). Corresponding right panel showing “input” controls (25 μg protein, total INS-1 lysates) confirmed the reduction in Munc18b levels and similar levels of indicated SNARE proteins. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments, with densitometry analyses in Supplementary Fig. 3. IP, immunoprecipitation.

In control scrambled siRNA-treated cells under nonstimulatory conditions, Syn-2 (Fig. 3B) and Syn-3 (Fig. 3C) bound Munc18b but very little VAMPs or SNAP25. Only upon stimulation, which presumably “activates” Munc18b, did we observe formation of full and distinct SNARE complexes, with Syn-3 preferring to bind VAMP8 and Syn-2 binding both VAMPs (VAMP2 > VAMP8). These results are consistent with our recent reports that VAMP8 formed complexes with Syn-2 and Syn-3 (but not Syn-1), which mediated the additional primary exocytosis of newcomer insulin SGs (24) and also SG-SG fusion, the later similarly observed in pancreatic acinar cells (25).

Remarkably, Munc18b depletion by Munc18b siRNA near-totally disabled Syn-2 (Fig. 3B) and Syn-3 (Fig. 3C) from forming complexes with both VAMPs and SNAP25. Disruption of SNARE complexes pulled down by Syn-3 antibody coimmunoprecipitation matched the ∼80% reduction in Munc18b levels (Supplementary Fig. 3); disruption of SNARE complexes pulled down by Syn-2 antibody was slightly less (∼70%). This is remarkable considering the total cellular levels of these SNARE proteins as shown in inputs; controls were unaffected and were expected to be available to participate in SNARE complex formation. Munc18b depletion did not affect the amount of Munc18a coimmunoprecipitated, indicating that formation of SNARE complexes by Syn-2 and Syn-3 is primarily through Munc18b. In contrast, Syn-1A coimmunoprecipitated endogenous Munc18a and remained able to form complexes with SNAP25 and VAMP2 (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Fig. 3), in spite of Munc18b depletion; this indicates that Munc18a and not Munc18b is the primary SM protein to activate Syn-1A to form SNARE complexes.

Gain-of-function Munc18b mutant promotes formation of distinct SM-activated SNARE complexes.

The ability of AdMunc18b-WT and -KR mutant to potentiate GSIS (Fig. 2C–E) suggests that additional Munc18b-activated SNARE complexes must be formed to mediate the additional exocytosis (Figs. 5–7). Association of Munc18b for native β-cell Syn likely within the context of assembled SNARE complexes, either at basal or stimulatory conditions, was unaffected by Munc18b-WT or Munc18b-KR (Fig. 4) but compromised by Munc18b-E59K. These results are different from our previous report (21) showing that in vitro Munc18b-KR reduced association and Munc18b-E59K displayed almost no binding to uncomplexed recombinant Syn. This emphasizes the importance of conducting mutant analysis in native cells, which we further examined showing that SM-activated SNARE complexes increased from basal to stimulated conditions. From AdMunc18b-KR– and AdMunc18b-WT–transduced cells, abundant SM-activated SNARE complexes were indeed precipitated more than controls, with Munc18b-KR associated with more Syn-1A, Syn-2, and Syn-3 SNARE complexes than was Munc18b-WT (analysis in Supplementary Fig. 4). Syn-3 (Fig. 4C), the putative Syn mediating SG-SG fusion (25), formed a complex with Munc18b to pull down exclusively VAMP8, along with SNAP25. A caveat in these coimmunoprecipitation studies is the possibility that Syn antibodies might be pulling down SM proteins independently from SNARE complexes and, hence, may not be SM/SNARE quaternary protein complexes per se. Our Munc18b antibodies, although more appropriate, are not suitable for coimmunoprecipitation assays.

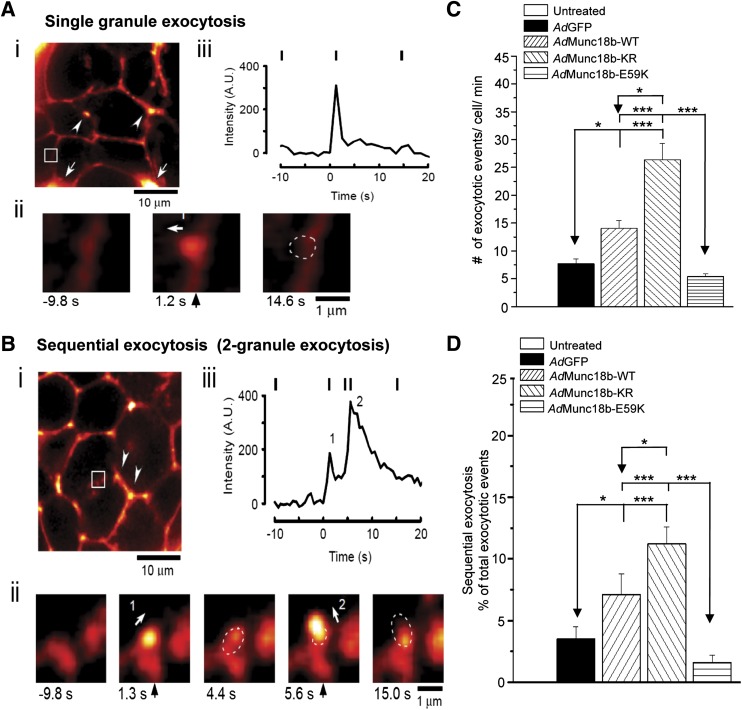

FIG. 5.

Munc18b mediates primary exocytosis and sequential SG-SG fusion in rat β-cells. A: Example of TEP imaging of single insulin SG exocytosis (single granule) in an AdGFP-transduced rat islet stimulated with 20 mmol/L glucose plus 10 nmol/L GLP-1 and 150 μm IBMX in a solution containing 0.3 mmol/L Alexa Fluor 594 hydrazide. An ω construction appeared when the SG(s) coalesced with the PM. B: Example of TEP imaging of sequential exocytosis (two granules) involving two SGs in an AdMunc18b-KR–transduced rat islet stimulated as in A. The Alexa fluorescence distinguishes several adjacent β-cells in the islet, along with small blood vessels (white arrowheads) and major blood vessels (white arrows) (i). White circle shows the position of an ω construction in a former panel (ii). An example of a single SG exocytosis shown in A with imaging interval of 1.2 s; in B, an example of 2-SG sequential events with imaging interval of 0.6 s. The numbers below each panel represent time after onset of exocytosis. Dashed circles show position of an ω construction in a former panel. Arrows point to the direction of SG fusion toward the cell interior. iii: Time courses of fluorescence at the area containing the exocytotic events. Vertical bars indicate the times when images in ii were acquired. The fluorescence value before exocytosis was set to zero. A and B: Scale bar represents 10 μm. C: Total number of exocytotic events calculated as number of exocytotic events/cell/min in β-cells from islets treated with AdGFP (8 islets, 68 cells), AdMunc18b-WT (7 islets, 44 cells), AdMunc18b-KR (6 islets, 58 cells), and AdMunc18b-E59K (5 islets, 75 cells) during a 10-min period of stimulation as in A. D: Fractions of total exocytotic events that are sequential exocytosis. The number of secondary exocytotic events considered to be sequential exocytosis is expressed as a percentage of total number of exocytotic events assessed in C. Data in C and D are shown as means ± SEM and analyzed by Steel-Dwass test for multiple comparisons using AdGFP as control. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. A.U., arbitrary units.

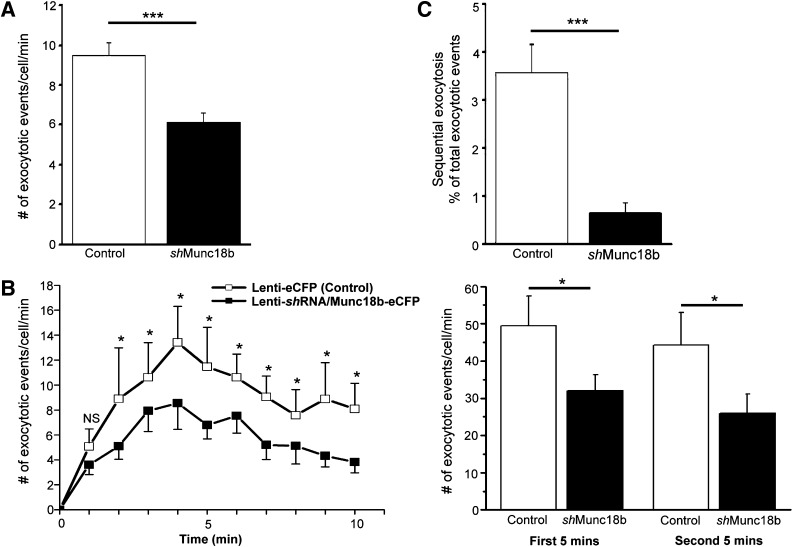

FIG. 7.

Munc18b depletion reduces primary and sequential exocytosis in rat β-cells. TEP images of single SG exocytosis and SG-SG fusions were analyzed from islets treated with lenti-shRNA/Munc18b-eCFP (67 cells, 8 islets) vs. lenti-eCFP (control, 48 cells, 8 islets) during 10-min period of stimulation with 20 mmol/L glucose plus 10 nmol/L GLP-1 and 150 μmol/L IBMX, and the following were calculated. A: Total number of exocytotic events. B: Number of exocytotic events at each indicated time interval in the 10-min recording. Right panel: Summation of the first 5 min and second 5 min of recording. C: Secondary exocytotic events considered to be sequential exocytosis expressed as a percentage of total number of exocytotic events assessed in A. Data shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

FIG. 4.

Munc18b gain-of-function mutant increases SM-activated SNARE complex formation, and INS-1 cells were transduced with AdMunc18 mutants, kept in nonstimulated (lanes 1–4) or simulated (lanes 5–8) condition as in Fig. 3 and subjected to coimmunoprecipitation (left panel) with antibodies against Syn-1A (A), Syn-2 (B), or Syn-3 (C). Exogenous Munc18b (tagged with Myc) expression was detected by Myc antibody. Corresponding right panel: Input controls (25 μg protein, total INS-1 lysates) showing similar levels of indicated SNARE proteins. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments, with densitometry analyses shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. IP, immunoprecipitation.

Since Munc18b also binds Syn-1A (26), Munc18b formed SNARE complexes with Syn-1A, SNAP25, and, preferentially, VAMP2 (Fig. 4A). These actions of Munc18b mutants on Syn-1A mimicked those of Munc18a and thus likely serve functions similar to those of Munc18a in mediating primary exocytosis. The order for Munc18b mutant proteins inducing such SM-SNARE complexes is KR > WT > GFP > E59K (analyses in Supplementary Fig. 4), corresponding to their abilities to potentiate biphasic GSIS (Fig. 2C and D). What is less clear is the role of Syn-2, whose role is also unclear in the broader field of exocytosis. The ability of Syn-2 to be induced by Munc18b proteins to form SNARE complexes (KR > WT) with VAMP2 and VAMP8 (Fig. 4B; Supplementary Fig. 4), taken along with reduction of such complexes by Munc18b depletion (Fig. 3B), suggests that Syn-2 might share redundant functions with Syn-1A and Syn-3, respectively.

Munc18b-E59K bound the Syn under basal conditions, but upon stimulation, it would not induce Syn to bind SNAP25 or VAMPs. Also, the levels of SM-activated SNARE complexes were similar to those of AdGFP or lower. Munc18b-E59K/Syn complexes were essentially functionally inert and did not significantly compete with endogenous Munc18b for any function essential for secretion. This explains why GSIS was similar between Munc18b-E59K and GFP control (Fig. 2C–E).

Taken together, the action of KR point mutant of Munc18b would mediate formation of activated states of SM-SNARE complexes (Fig. 4). Formation of SNARE complex by glucose stimulation, and its potentiation by Munc18b, is consistent with poststimulus assembly of SNAREs (23,27) in insulin exocytosis.

Munc18b gain-of-function promotes sequential SG-SG fusion and primary exocytosis.

We previously reported sequential insulin SG-SG fusion, visualized by two-photon imaging, occurs in β-cells (7). This process is mediated by diffusion of SNAP25 from the PM into sequentially fused SGs after assembly of SNARE complexes (6). We thus postulate that Munc18b-activated Syn-3/SNAP25/VAMP8 complexes might increase sequential SG-SG fusion and examined whether overexpression of the Munc18b mutants could influence primary exocytosis and SG-SG fusions by two-photon imaging analysis (6,7). Here, we also used GLP-1 plus IBMX to maximally potentiate 20 mmol/L glucose-stimulated insulin exocytosis, including maximal induction of sequential SG-SG exocytosis (22).

First, we showed examples of single insulin SG fusion and sequential SG-SG exocytosis. Fig. 5A shows a full fusion exocytosis of a single SG (Fig. 5Aii from inset in Fig. 5Ai) from AdGFP-transduced rat islet, with each vertical indicator temporally tracking the analysis of kinetics of these events in Fig. 5Aiii, corresponding to images in Fig. 5Aii. This represents fusion of an insulin SG at 1.2 s (white arrow, Fig. 5Aii, middle image, indicates direction of fusion); upon discharge of contents at 14.6 s (dotted circle, Fig. 5Aii, right image), it collapses into the PM to create an ω figure. The most frequent mode of sequential exocytosis observed was that of two SGs: an example is shown in Fig. 5B in AdMunc18b-KR–transduced islet (Fig. 5Bii, inset in islet in Fig. 5Bi). Here, the first SG fuses with PM at 1.3 s (arrow 1 indicates direction of fusion in Fig. 5Bii) and then partially empties (dashed circle at 4.4 s in Fig. 5Bii). Then, <2 s later, it is followed by fusion of a second SG at 5.6 s coming from another direction (arrow 2) deeper into the cytosol relative to the first exocytosing SG. This resulted in a larger and brighter area of fluorescence intensity (temporal analysis in Fig. 5Biii), since it emanated from a 2-SG fusion and is followed by a slower decline (than Fig. 5Aiii) in fluorescence intensity reflecting insulin cargo emptying and eventual collapse of the compound granule onto the PM.

Using this analysis, we counted the total number of exocytotic events as determined by number of ω figures (exocytotic events/cell/min [Fig. 5C]), which showed that AdMunc18b-KR induced the most exocytotic events (26.39 ± 2.89, 58 cells/6 islets), followed by AdMunc18b-WT (14.06 ± 1.39, 44 cells/7 islets), AdGFP (7.71 ± 0.89, 68 cells/8 islets), and lastly, AdMunc18b-E59K (5.4 ± 0.53, 75 cells/5 islets). We then examined how many of these exocytotic events exhibited sequential exocytosis (Fig. 5D). AdMunc18b-KR (11.2 ± 1.4%) and AdMunc18b-WT (7.1 ± 1.7%) induced ∼3.2 and 2.0 times higher sequential exocytosis, respectively, than did AdGFP-expressing cells (3.5 ± 1.0%, P < 0.05). Sequential exocytosis constituted only 1.6 ± 0.6% of total exocytotic events in AdMunc18b-E59K–expressing β-cells. We assessed the percentage of cells undergoing sequential exocytosis (versus no sequential exocytosis), which was higher in AdMunc18b-KR (74.1%)- and AdMunc18b-WT (54.5%)-transduced cells compared with AdGFP (30.9%) and AdMunc18b-E59K (13.3%) expression. These results indicate that Munc18b-KR and Munc18-WT expression recruited more β-cells to exhibit sequential exocytosis.

Considering that AdMunc18b-KR–infected β-cells exhibited the highest percentage (11.2%) of exocytotic events being sequential SG-SG fusion, the majority of the increase in total exocytosis events in Fig. 5C, ∼89%, is thus primary exocytosis. For AdMunc18b-WT expression, primary exocytosis accounted for 93% of total exocytotic events. It therefore appears that it is the combination of a large increase in both primary exocytosis and SG-SG fusions that accounts for overall increase in biphasic GSIS caused by Munc18b-KR and -WT overexpression observed in Fig. 2C–E. Munc18b-E59K expression apparently could not induce a significant dominant-negative effect on exocytosis by competition with endogenous Munc18b and thus did not cause detectable reduction in GSIS (Fig. 2C–E).

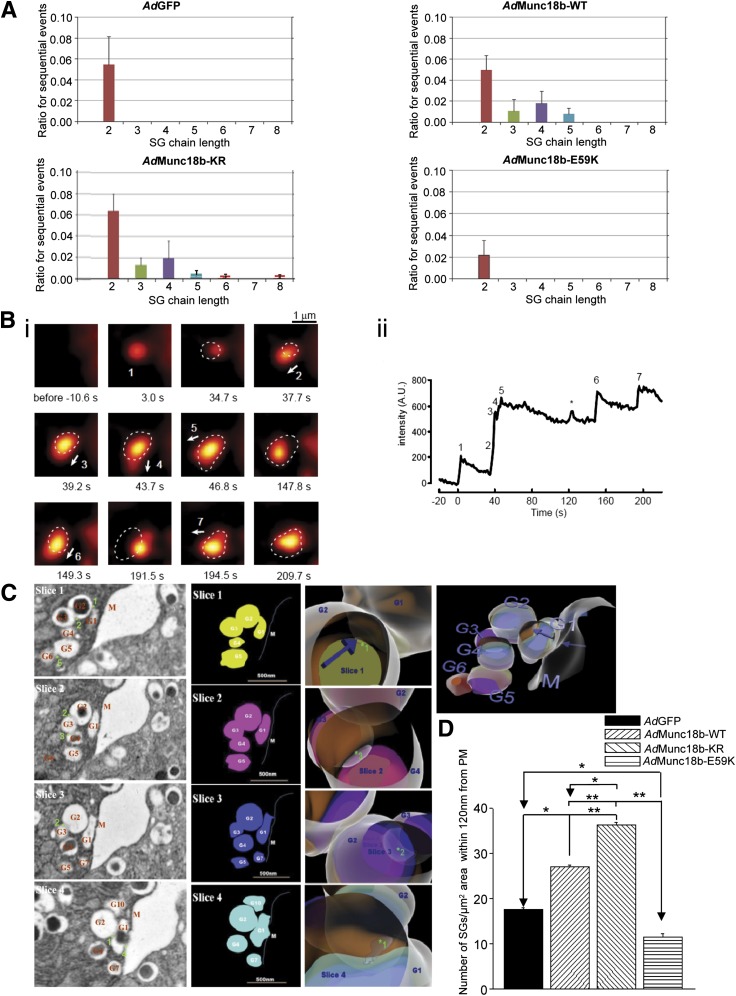

Munc18b can mediate long-chain sequential SG fusion.

Long-chain sequential exocytosis is the mode of exocytosis in highly efficient secretory cells like mast cells (28), eosinophils (5), and pancreatic acinar cells but not in less efficient β-cells. The molecular mechanism underlying long-chain sequential exocytosis is unknown. We postulated that upregulating Munc18b expression or action could induce β-cells to increase the number of SGs participating in long-chain sequential SG-SG fusion. We therefore assessed the proportions of the different extent of sequential SG fusions as determined by number of ω figures (Fig. 6A). Both AdMunc18b-KR– and AdMunc18b-WT–transduced cells had higher-order SG-SG fusions of up to five long-chain sequential SG-SG fusions. AdGFP cells only had up to 2-SG sequential fusions, as is the case with AdMunc18b-E59K, with the latter at much reduced frequency. The distinct increases in fluorescence predict the sizes of SGs of ~0.3 μm, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. This value is consistent with reported EM analysis of insulin SG size (as in Fig. 6C) and strongly supports our interpretation that increases in fluorescence in our two-photon studies genuinely reflected exocytosis of insulin SGs.

FIG. 6.

Munc18b mediates long-chain sequential SG fusion. A: The ordinate represents the ratios for increasing chain length of sequential SG fusion events relative to total numbers of exocytotic events from >20 β-cells (>2 rat islets) transfected with AdGFP, AdMunc18b-WT, AdMunc18b-KR, and AdMunc18b-E59K. Here, we also assessed the distinct increase in fluorescence that predicts the sizes of SGs, which was ∼0.3 μm, shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. B: TEP imaging of long-chain sequential exocytosis of insulin SGs in a rat β-cell treated with AdMunc18b-KR. i: Sequential images for Supplementary Movie 1 of an islet stimulated with 20 mmol/L glucose plus 10 nmol/L GLP-1 and 150 μmol/L IBMX. Dashed circles show positions of an ω construction in a former panel. Arrows indicate the direction of oncoming SG undergoing sequential fusion. ii: Time course of fluorescent intensity within the region that contained all exocytotic events shown in i. *Independent single exocytotic event, occasionally seen close to compound SGs. Scale bars, 1 μm. C: EM demonstrating long-chain sequential exocytosis of insulin SGs in an islet treated with AdMunc18b-KR. An example of AdMunc18b-KR–transduced islet stimulated with 20 mmol/L glucose plus 10 nmol/L GLP-1 and 150 μmol/L IBMX that illustrates long-chain sequential fusion of SG-SG events up to six SGs in length. Left panel: 70-nm-thick sections cut serially, showing only four of eight consecutive slices containing the SG-SG fusions. G plus number (in red) indicates the numbered SGs involved in long-chain exocytosis, M (in red) indicates PM, and numbered asterisks (in green) indicate SG-SG fusion sites. Scale bar, 500 nm. Cartoon panels: SG-SG fusion events constructed from the EM images in left panel and converted into cartoons (first column) followed by reconstruction into a three-dimensional image (third column). The second column shows blowups of this three-dimensional image that can be rotated to selectively visualize fusion pores between indicated SGs, which correspond to raw EM images in the left panel. Blue arrows indicate locations of fusion pore openings. A second example of a 7-SG fusion is shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. D: Insulin SGs within 120 nm from PM calculated as SG/µm2 area, expressed as means ± SEM of three to four independent experiments. AdGFP: 17 sections. AdMunc18b-KR: 16 sections. AdMunc18b-WT: 17 sections. AdMunc18b-E59K: 21 sections. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. A.U., arbitrary units.

We occasionally found very long-chain sequential SG fusions in AdMunc18b-KR–expressing β-cells (Fig. 6B, corresponding to Supplementary Movie 1), which shows sequential fusion of seven insulin SGs. The time course in this exocytosis event shows an initial delay in fusion of the second SG (Fig. 6Bii) followed by rapid successive fusions up to the fifth SG, whose positions are indicated by dashed circles (Fig. 6Bi); the temporal analysis tracking kinetics of fusion events is correspondingly numbered in Fig. 6Bii (Supplementary Movie 1). The diameters of puncta are noted to actually increase with each successive fusion. Supplementary Movie 1 better shows events 2, 3, and 4 to be associated with abrupt changes in shapes of the compound SGs in addition to increases in fluorescence. In Fig. 6Bi, arrows shown indicate direction of exocytosis of individual SGs, which are distinct from event to event. The focal plane was not deviated during acquisition of images (see Supplementary Fig. 6) where low-magnification images demonstrated that landmarks were not changed at all. This rapid successive fusion might be due to “primed” insulin SGs (3rd–5th SGs), and resulting sustained plateau of fluorescence intensity (Fig. 6Bii) might reflect slower flattening of compound SGs. Note that positions of compound SGs (point of highest fluorescent intensity) resulting from each sequential SG-SG fusion tend to shift from previous positions (dashed circles, Fig. 6Bi). This suggests that fusion pores of primary SGs were stably maintained even though its position was altered by subsequent sequential exocytosis. These events are also better observed in Supplementary Movie 1.

We next visualized these very long chains of sequentially fused SGs induced by AdMunc18b-KR expression by EM (Fig. 6C). Since a single EM slice (70 nm thick) will not capture such a large number of sequential-fused SGs (encompassing 2–3 SG diameters, ∼300 nm diameter/SG), we sectioned numerous consecutive 70-nm-thick slices. Fig. 6C shows EM images from four consecutive slices (of eight) exhibiting distinct SG-SG fusions (green-numbered asterisks) visualized in different slices. Here, exocytotic fusion of SG1 (G1) formed a large fusion pore with PM sufficient to empty the insulin cargo (slice 4). Note that some SGs appeared deceivingly empty on one slice (G2, slices 3 and 4), yet actually have complete core cargo in another slice (G2, slice 1). We created cartoons of these four slices (left cartoons) to reconstruct a three-dimensional image (middle and right cartoons) that more clearly show the relationships of these six sequentially fused SGs (fusion pores indicated by numbered asterisks in EM images and blow-up cartoon images [middle cartoons]). Supplementary Fig. 7 shows another example of a long-chain (seven SGs) sequential fusion, with G2 and G7 undergoing fusion with PM. In both (and other) examples, we consistently saw sequentially fused SGs arranged in parallel and close to the PM, as was the case with our two-photon study, where compound SGs never reached further than 2 μm from the PM. From these EM images, we quantified the number of SGs within 120 nm from the PM that would participate in these exocytotic events (Fig. 6D), which was increased by ∼2.1 times in AdMunc18b-KR (36.42 ± 0.5 SGs; P < 0.01) compared with AdGFP (17.5 ± 0.6 SGs) cells and ∼1.5 times in AdMunc18b-WT cells (27.11 ± 0.4 SGs; P < 0.05) and mildly reduced (by ∼27%) in AdMunc18b-E59K–infected cells (11.52 ± 0.7 SGs; P < 0.05).

Depletion of endogenous Munc18b reduces primary exocytosis by half and completely abrogates sequential SG-SG fusion.

Finally, we examined how primary and sequential exocytoses would be diminished by lenti-Munc18b-shRNA depletion of endogenous Munc18b in β-cells. We compared these exocytotic events in eCFP-expressing (therefore Munc18b depleted) β-cells of lenti-Munc18b shRNA-eCFP–treated (48 h) islets versus control lenti-eCFP–expressing β-cells. Total exocytotic events (Fig. 7A) in Munc18b-depleted (67 cells/8 islets) versus control β-cells (48 cells/8 islets) over a 10-min period of recording were 9.47 ± 0.65 vs. 6.1 ± 0.50, respectively, which is an ∼40% reduction (P < 0.001). The distribution of these exocytotic events over time (exocytotic events/cell [Fig. 7B]) showed a 35% reduction (49.4 ± 7.9 vs. 31.9 ± 4.2 for control and Munc18b shRNA, respectively; P < 0.05) in the first 5 min and 41% reduction (44.2 ± 8.8 vs. 26 ± 5.1; P < 0.05) in the second 5 min (Fig. 7B). This extent and pattern of sustained reduction of exocytosis over time remarkably mimicked the sustained suppression of GSIS observed in the islet perifusion results (Fig. 1E). We examined how many of these exocytotic events exhibited sequential exocytosis (Fig. 7C). Of the total number of exocytotic events, sequential exocytotic events in control β-cells constituted only 3.57 ± 0.59%, which is consistent with our previous report (7). Remarkably, Munc18b depletion reduced this to 0.6 ± 0.22%, which is an 83% reduction (P < 0.001), indicating almost total abrogation.

DISCUSSION

This work revealed that Munc18b-mediated pathways in β-cells account for one-half of the physiologic biphasic GSIS and that Munc18b mediated glucose-induced assembly of SNAREs to effect primary exocytosis and sequential SG-SG fusion. We discuss several points below that led us to these conclusions.

First, Munc18b deletion abolished one-half of primary exocytosis and almost all sequential SG-SG fusion. Conversely, overexpression of Munc18b increased insulin exocytosis as previously reported (29), and overexpression of dominant-positive Munc18b-KR mutant greatly upregulated recruitment of insulin SGs to PM to undergo increased primary exocytosis and sequential SG-SG fusions, leading to ∼50% (Munc18b-WT) and ∼100% (Munc18b-KR) increase in biphasic GSIS, respectively. Munc18b-E59K caused some disruption of SNARE complexes but had only minor insignificant reduction on exocytosis events, likely because of promiscuous binding of endogenous Munc18b to several SNARE complexes conferring redundant actions on exocytosis. Although SG-SG fusion contributed to a small degree (3–12%) of total insulin exocytosis, it may play a more important role in other experimental conditions, such as cholinergic stimulation shown to induce compound exocytosis (30).

Second, only upon stimulation would Munc18b become activated to effect formation of distinct SNARE complexes required for SG-SG fusion and primary exocytosis. Munc18b on SGs could bind Syn-1A on PM perhaps during SG approach to the PM; this SM-activated SNARE complex may also participate in primary exocytosis. These roles of Munc18b are similar to Munc18a (18) and Munc18c (31) in inducing formation of their respective SNARE complexes. These actions of Munc18b are in line with reports showing that glucose stimulation induces SNARE assembly (23) and vesicle docking (32,33) leading to insulin exocytosis. Activation of Munc18b is likely by protein kinase C phosphorylation, reminiscent of Munc18a (34), likely at Ser313, that is conserved in both.

Third, Munc18b-KR–activated SNARE complexes represent “activated” conformations superior to WT-Munc18b–activated complexes, similar to the Munc18a-SNARE complex (14,15). Munc18b-KR–activated SNARE complexes thus enabled enhanced efficiency of SG-SG and SG-PM fusions resulting in larger increases in GSIS and GLP-1–potentiated GSIS than Munc18b-WT–activated SNARE complexes. We estimate in Munc18b-KR–expressing islets that sequential insulin exocytosis per se stimulated by maximal cAMP enhancement was augmented three times (11%), with infrequent artificially enhanced very-long-chain sequential SG fusion occurring more in Munc18-KR–transduced β-cells, along with recruitment of more β-cells to exhibit sequential exocytosis. This is a large increase considering that sequential exocytosis (normally only 2–3 SGs) occurs normally in only 2–3% of β-cells (6,7).

Finally, what are the v-SNAREs and t-SNAREs activated by Munc18b that specifically mediate SG-SG fusion and primary exocytosis? We recently reported that primary exocytosis of newcomer insulin SG is mediated by VAMP8 (24) and Syn-3 (35) and that insulin SG-SG fusion is mediated Syn-3 (35). Indeed, both these SNARE proteins were coimmunoprecipitated by Munc18b in this study. Nonetheless, some of the increase in primary exocytosis is likely mediated by Syn-1A (19), which could also be activated by Munc18b to form SM-SNARE complexes with VAMP2. It is conceivable that enhancing these actions (or expression) of Munc18b-activated SNARE complexes in mobilizing more insulin SGs (newcomer SGs) to PM to undergo sequential SG-SG fusion and primary exocytosis, which are responsive to GLP-1 stimulation, could compensate and be deployed to treat the exocytotic defects of diabetic β-cells to attain normoglycemic control (36).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants to H.Y.G. (Canadian Institute of Health Research [CIHR] MOP89889 and MOP 86544), to H.K. (Grants-in-Aids for Specially Promoted Area No. 2000009; Global COE Program [Integrative Life Science Based on the Study of Biosignaling Mechanisms] from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan; and CREST of Japan Science and Technology Agency, a research grant from Human Frontier Science Program), and to V.M.O. (Academy of Finland grants 50641 and 121457 and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation). P.P.L.L. was funded by doctoral studentships from Canadian Digestive Health Foundation and CIHR. S.D. is funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from Banting and Best Diabetes Center, University of Toronto.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

P.P.L.L. formulated the original hypothesis, designed and performed the molecular and biochemical experiments, performed the EM experiments, wrote the manuscript, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. M.O. performed the two-photon imaging experiments and analysis, wrote the manuscript, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. S.D. performed the molecular and biochemical experiments, performed the immunoprecipitation studies, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. Y.H. performed the molecular and biochemical experiments, performed the EM experiments, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. T.Q. performed islet perfusion experiments, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. T.L. performed the confocal quantification analysis, performed islet perfusion experiments, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. D.Z. performed the EM experiments, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. Y.K. performed the molecular and biochemical experiments, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. Y.L. performed islet perfusion experiments, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. M.K. subcloned the Munc18b mutant constructs into adenoviruses, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. L.X. performed the EM experiments, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. W.C.Y.W. performed the molecular and biochemical experiments, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. N.-R.B. and S.S. designed and generated the Munc18b lenti-shRNA, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. V.M.O. wrote the manuscript, designed the Munc18b mutant constructs, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. N.T. performed the two-photon imaging experiments and analysis, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. H.K. formulated the original hypothesis, wrote the manuscript, performed the two-photon imaging experiments and analysis, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. H.Y.G. formulated the original hypothesis, designed the molecular and biochemical experiments, wrote the manuscript, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. H.Y.G. is the guarantor of this work and as such had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db12-1380/-/DC1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Burnett MA, Matthews DR, Turner RC. Similar reduction of first- and second-phase B-cell responses at three different glucose levels in type II diabetes and the effect of gliclazide therapy. Metabolism 1989;38:767–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwan EP, Gaisano HY. Rescuing the subprime meltdown in insulin exocytosis in diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009;1152:154–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jewell JL, Oh E, Thurmond DC. Exocytosis mechanisms underlying insulin release and glucose uptake: conserved roles for Munc18c and syntaxin 4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2010;298:R517–R531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez JM, Neher E, Gomperts BD. Capacitance measurements reveal stepwise fusion events in degranulating mast cells. Nature 1984;312:453–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hafez I, Stolpe A, Lindau M. Compound exocytosis and cumulative fusion in eosinophils. J Biol Chem 2003;278:44921–44928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi N, Hatakeyama H, Okado H, et al. Sequential exocytosis of insulin granules is associated with redistribution of SNAP25. J Cell Biol 2004;165:255–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi N, Kishimoto T, Nemoto T, Kadowaki T, Kasai H. Fusion pore dynamics and insulin granule exocytosis in the pancreatic islet. Science 2002;297:1349–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasai H, Takahashi N, Tokumaru H. Distinct initial SNARE configurations underlying the diversity of exocytosis. Physiol Rev 2012;92:1915–1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Südhof TC, Rothman JE. Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science 2009;323:474–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgoyne RD, Barclay JW, Ciufo LF, Graham ME, Handley MT, Morgan A. The functions of Munc18-1 in regulated exocytosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009;1152:76–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizo J, Rosenmund C. Synaptic vesicle fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008;15:665–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deák F, Xu Y, Chang WP, et al. Munc18-1 binding to the neuronal SNARE complex controls synaptic vesicle priming. J Cell Biol 2009;184:751–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voets T, Toonen RF, Brian EC, et al. Munc18-1 promotes large dense-core vesicle docking. Neuron 2001;31:581–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber SH, Rah JC, Min SW, et al. Conformational switch of syntaxin-1 controls synaptic vesicle fusion. Science 2008;321:1507–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han L, Jiang T, Han GA, et al. Rescue of Munc18-1 and -2 double knockdown reveals the essential functions of interaction between Munc18 and closed syntaxin in PC12 cells. Mol Biol Cell 2009;20:4962–4975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arunachalam L, Han L, Tassew NG, et al. Munc18-1 is critical for plasma membrane localization of syntaxin1 but not of SNAP-25 in PC12 cells. Mol Biol Cell 2008;19:722–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodkey TL, Liu S, Barry M, McNew JA. Munc18a scaffolds SNARE assembly to promote membrane fusion. Mol Biol Cell 2008;19:5422–5434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen J, Tareste DC, Paumet F, Rothman JE, Melia TJ. Selective activation of cognate SNAREpins by Sec1/Munc18 proteins. Cell 2007;128:183–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohara-Imaizumi M, Fujiwara T, Nakamichi Y, et al. Imaging analysis reveals mechanistic differences between first- and second-phase insulin exocytosis. J Cell Biol 2007;177:695–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh E, Kalwat MA, Kim MJ, Verhage M, Thurmond DC. Munc18-1 regulates first-phase insulin release by promoting granule docking to multiple syntaxin isoforms. J Biol Chem 2012;287:25821–25833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kauppi M, Wohlfahrt G, Olkkonen VM. Analysis of the Munc18b-syntaxin binding interface. Use of a mutant Munc18b to dissect the functions of syntaxins 2 and 3. J Biol Chem 2002;277:43973–43979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwan EP, Gaisano HY. Glucagon-like peptide 1 regulates sequential and compound exocytosis in pancreatic islet beta-cells. Diabetes 2005;54:2734–2743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi N, Hatakeyama H, Okado H, Noguchi J, Ohno M, Kasai H. SNARE conformational changes that prepare vesicles for exocytosis. Cell Metab 2010;12:19–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu D, Zhang Y, Lam PP, et al. Dual role of VAMP8 in regulating insulin exocytosis and islet β cell growth. Cell Metab 2012;16:238–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cosen-Binker LI, Binker MG, Wang CC, Hong W, Gaisano HY. VAMP8 is the v-SNARE that mediates basolateral exocytosis in a mouse model of alcoholic pancreatitis. J Clin Invest 2008;118:2535–2551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hata Y, Slaughter CA, Südhof TC. Synaptic vesicle fusion complex contains unc-18 homologue bound to syntaxin. Nature 1993;366:347–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song WJ, Seshadri M, Ashraf U, et al. Snapin mediates incretin action and augments glucose-dependent insulin secretion. Cell Metab 2011;13:308–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarez de Toledo G, Fernandez JM. Compound versus multigranular exocytosis in peritoneal mast cells. J Gen Physiol 1990;95:397–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandic SA, Skelin M, Johansson JU, Rupnik MS, Berggren PO, Bark C. Munc18-1 and Munc18-2 proteins modulate beta-cell Ca2+ sensitivity and kinetics of insulin exocytosis differently. J Biol Chem 2011;286:28026–28040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoppa MB, Jones E, Karanauskaite J, et al. Multivesicular exocytosis in rat pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 2012;55:1001–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Latham CF, Lopez JA, Hu SH, et al. Molecular dissection of the Munc18c/syntaxin4 interaction: implications for regulation of membrane trafficking. Traffic 2006;7:1408–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibasaki T, Takahashi H, Miki T, et al. Essential role of Epac2/Rap1 signaling in regulation of insulin granule dynamics by cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:19333–19338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasai K, Fujita T, Gomi H, Izumi T. Docking is not a prerequisite but a temporal constraint for fusion of secretory granules. Traffic 2008;9:1191–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wierda KD, Toonen RF, de Wit H, Brussaard AB, Verhage M. Interdependence of PKC-dependent and PKC-independent pathways for presynaptic plasticity. Neuron 2007;54:275–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu D, Koo E, Kwan E, et al. Syntaxin-3 regulates newcomer insulin granule exocytosis and compound fusion in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 2013;56:359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaisano HY. Deploying insulin granule-granule fusion to rescue deficient insulin secretion in diabetes. Diabetologia 2012;55:877–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.