Abstract

Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma (HCCC) is a rare minor salivary gland tumor made up of clear cells and forming cords and nests in a hyalinized stroma. The overall outcome is excellent with only occasional metastatic spread. HCCC has a wide differential diagnosis including other clear cell-containing tumors, such as epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and myoepithelial carcinoma. HCCC is currently classified as a “clear cell adenocarcinoma” by the AFIP and as “clear cell carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS)” by the World Health Organization (WHO). It is considered by the WHO to be a diagnosis of exclusion. Since the original description in 1994, there have been few new insights into HCCC, until recently. Dardick re-examined the features of HCCC, including the original electron microscopic images, and concluded that HCCC is a squamous lesion, at odds with the above nomenclature. Bilodeau et al. recently showed that this tumor essentially cannot be separated reliably from clear cell odontogenic carcinoma (CCOC) except by location. Antonescu et al. recently identified a consistent EWSR1-ATF1 fusion in HCCC. Bilodeau et al. subsequently argued a link between these two entities, with evidence of similar EWSR1 and ATF1 rearrangements in CCOC. This molecular signature is not present in other clear cell mimics. Cases with recurrence, metastasis, high-grade features and other alternative morphologies or presentations have also been seen and proven by molecular analysis to be HCCC. In the molecular era, HCCC can no longer be seen as a diagnosis of exclusion. It is neither an adenocarcinoma nor a “not otherwise specified” tumor, as the AFIP and WHO currently classify it. This review provides an in-depth look at the current state of knowledge of HCCC from morphology to molecular features. New developments and personal insights are provided that help identify and properly classify this lesion.

Keywords: Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma, Salivary gland, EWSR1, EWSR1-ATF1, Myoepithelial, Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Background

Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma (HCCC) was first described by Milchgrub et al. in 1994 as a rare minor salivary gland carcinoma made up of clear cells forming cords and nests in a hyalinized stroma [1]. This tumor was speculated to be previously called or confused with monomorphic variants of epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, mucin-depleted mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and myoepithelial carcinoma. It was separated from these entities because of its lack of apparent squamous, mucinous, and myoepithelial differentiation [1]. The tumor showed low-grade morphology and good overall outcome with only occasional metastatic spread. HCCC is currently classified as a “clear cell adenocarcinoma” in the AFIP fascicle [2] and “clear cell carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS)” by the World Health Organization (WHO) “blue book” on head and neck tumors [3]. It is considered by the WHO to be a diagnosis of exclusion. Since then, numerous small case series and case reports have been described [4–6], but none had added new insights into HCCC until recently.

Issues with nomenclature and proposed lines of differentiation have recently been raised [7, 8]. For instance, Dardick re-examined the features of HCCC, including the original electron microscopic images and concluded that HCCC is a squamous lesion. Bilodeau et al. recently showed that this tumor essentially cannot be separated reliably from clear cell odontogenic carcinoma (CCOC) except by location [8]. Antonescu et al. recently identified a consistent EWSR1-ATF1 fusion in HCCC [9] and Bilodeau et al. followed this up with evidence of similar EWSR1 and ATF1 rearrangements in CCOC, linking these two entities [10]. Notably, this molecular signature is not present in other clear cell mimics [9]. Cases with recurrence, metastasis, high-grade features and other alternative morphologies can also be seen in our experience. The following review provides an in-depth look at the current state of knowledge of HCCC, from morphology to immunohistochemistry and molecular findings. An attempt will be made to address other clues and issues around diagnosis that we have recently encountered.

Clinical, Gross and Histologic Features

The majority of HCCCs present as a mass inside the oral cavity and are presumed to arise from minor salivary glands [1]. A minority can present as major salivary glands, nasopharyngeal or laryngeal tumors as well [1, 9]. A single lacrimal/orbital case has also been reported [4]. Primary nasal cavity and paranasal sinus locations have not been described thus far. Minor salivary gland involvement accounts for two-thirds of cases, according to the AFIP [2]; however, in our recent publication [9], and based on our experience with subsequent cases seen in our institution, the number is probably higher (in the order of 80 %). The tumors are generally submucosal, typically present as a swelling and may occasionally ulcerate [2]. Presentation with signs or symptoms of cranial nerve invasion may also rarely occur (personal observation). Although a long time lag has been quoted in the presentation of some tumors, the majority have a short history before a patient seeks medical attention. These lesions are often found on routine dental examination and so many are biopsied and examined first by oral surgeons or oral pathologists, in our experience.

HCCC usually arises in patients in their 60s or older; however, a broad age range is noted [2, 3, 9]. It is quoted as having equal sex distribution, although we have seen a slight female predominance in our own series [9]. The most common sites of origin are the palate and tongue base, followed by the mobile tongue and other minor salivary gland locations. These include the lip, retromolar trigone, buccal mucosa, floor of mouth and gingiva. These latter cases may sometimes invade bone and the distinction between a mucosal and primary bone tumor may be difficult, especially since “central” examples of HCCC have been described [10, 11]. The tumor size ranges between 1.0 and 4.5 cm (mean 2.0–3.0 cm) and has a white-tan cut surface grossly [3, 9]. Gross cystic change is unusual. HCCCs may appear relatively circumscribed but lack encapsulation and they have a tendency to show infiltration of the surrounding tissues, despite this grossly circumscribed appearance.

Histologically, there is a relatively wide range of appearance of HCCC tumor cells. The predominance of clear cells is seen in a minority of cases and the tumor cells actually often have pale eosinophilic cytoplasm rather than clear cytoplasm, or they may have a mixture of both (Fig. 1a). Tumors with virtually no clear cells can be seen but they generally retain the same overall growth pattern as typical examples of HCCC (Fig. 1b). Namely, the cells are arranged in small nests, short and long cords, interconnecting thin trabecular structures and single cells. There is a tendency for the cells in the center of the mass to be surrounded by, or admixed with a hyalinized basement membrane-like material (Fig. 1c). This is often sharply-demarcated from a desmoplastic or fibrocellular stroma that may sometimes appear myxoid and mimic pleomorphic adenoma. This juxtaposition of two stroma types within the tumor is essentially pathognomonic for the diagnosis of HCCC and is seen in most, but not all cases. The presence of the hyalinized stroma in a cribriform arrangement may also mimic other more common salivary gland tumors, particularly in cases that are clear cell-poor (Fig. 1d). Tumor cells at the periphery of the mass have a greater tendency for nest formation and for wide infiltration without the stromal deposition or desmoplastic response. Some of these will also exist as short thin cords between skeletal muscle fibres and may be very difficult to appreciate on H&E (Fig. 2a). These subtle nests are more apparent on immunohistochemical stains (see below).

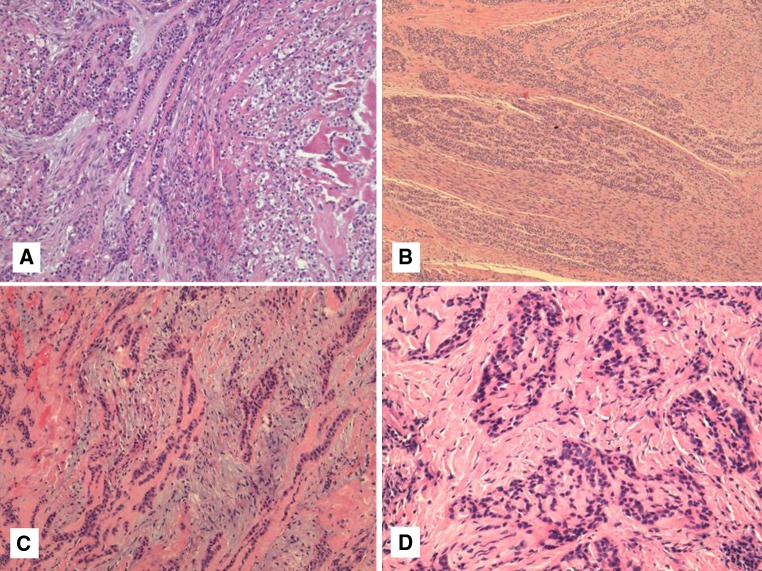

Fig. 1.

a–d Typical example of hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma (HCCC) showing a combination of cords and nests of clear and eosinophilic cells in a hyalinized background (a). Some HCCC show areas with no striking clearing but show a similar growth pattern. This case shows prominent perineural invasion as well (b). The presence of a fibrocellular stroma juxtaposed to hyalinized stroma is a common finding (c). The hyalinization may mimic cribriform growth (d)

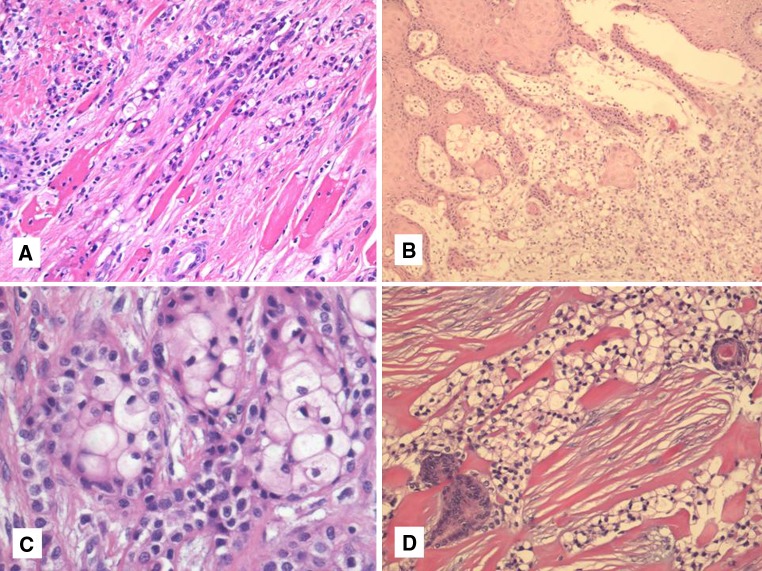

Fig. 2.

a–d Skeletal muscle infiltration is common and sometimes subtle (a) Almost half of oral cavity examples of HCCC show connection to the surface epithelium (b). Occasional squamous differentiation can be seen (c). True ductal differentiation is rare. More commonly, entrapped ducts can be seen particularly in parotid examples (d)

HCCC often connects to the surface mucosal epithelium either abruptly or as a pagetoid-like growth of single cells. It may be accompanied by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epithelium. This is seen in 44 % of oral cavity examples (Fig. 2b). Focal squamous differentiation of tumour nests can also be seen on occasion (Fig. 2c). Perineural (PNI) and intraneural invasion are typical and occur in almost half of all cases [9] (Fig. 1b). This number is probably an underestimate, as many cases that are negative for PNI represent small biopsies. Other focal findings include occasional duct formation. This finding may occasionally be real but in most cases represents entrapped ducts (Fig. 2d). This was particularly common in parotid examples [9] and absent in oral examples, further supporting duct entrapment rather than true glands in most instances. The individual cells are small and bland with minimal atypia. Some “rasinoid” or “popcorn” nuclear membrane irregularities can be noted, as can occasional pseudonuclear inclusions, but the nuclear size shows minimal variation (Fig. 3a). Multivacuolation or pseudosebaceous cells may be seen. Mitotic figures are rare and number <1 per 10 HPFs with only occasional cases showing up to 5 MFs per 10 HPFs. Nucleoli are small or inconspicuous. Necrosis is generally absent. Mucinous cells are sometimes readily apparent, but careful examination with a mucicarmine special stain reveals dot-like or frank intracellular mucin in a high proportion of cases [9] (Fig. 3b). The clear cells show granular PAS positivity and diastase sensitivity, indicative of glycogen in the cytoplasm. These stains also highlight the hyalinized stroma. A Congo red is negative in all cases, despite the stroma appearing similar to amyloid [1]. HCCCs lack papillary growth, chondroid stroma or goblet cell-lined cystic spaces. When present, small cystic spaces are lined by typical clear cells and not mucinous cells (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

a–d Most HCCC cases show minimal atypia with small bland nuclei (a). Mucinous differentiation is seen in almost half of all cases, usually focally but sometimes diffusely (b). Occasional small cystic spaces can be seen but are not lined by mucinous cells (c). Virtually all cases are positive for one or both of p63 and HMWK (p63 shown here) (d)

Immunohistochemical and Ultrastructural Findings

The vast majority of tumors are diffusely positive for pancytokeratin. Almost all cases are positive for 34βE12 and p63, suggestive of squamous differentiation (Fig. 3d). Positivity for CK14 is also common. Many cases are focally or diffusely positive for EMA, CK7, CK19 and CAM5.2, as well. They are almost invariably negative for S100, SMA, MSA, calponin and GFAP, ruling out myoepithelial differentiation. The hyalinized stroma is positive for collagen I and fibronectin but negative for collagen IV and laminin, arguing against this hyalinized stroma being basement membrane material [12]. Collagen IV and laminin are only positive in a thin layer around tumour nests [12]. Ultrastructurally, the tumors have been shown to have tonofilaments, desmosomes and glycogen [1, 3, 13]. These features are also suggestive of squamous differentiation in this tumor entity [7]. This is in line with the usual oral cavity location and frequent connection to the surface mucosal epithelium. Additional findings on electron microscopy include some basal lamina reduplication [12].

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis is wide and includes a number of neoplasms with clear cell change. A summary of the potential mimics of HCCC is listed in Table 1. This has long been the source of diagnostic confusion, with morphologic overlap between entities quite high [14, 15]. The usual suspects and other rare tumors considered in the differential diagnosis include clear cell variants of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), myoepithelial carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, clear cell odontogenic carcinoma, calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor (in bone), epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, oncocytoma, myoepithelioma and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. In addition, tumors with a cribriform growth pattern and arising in the oral cavity, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, have to be considered, despite their usual lack of clear cell differentiation. Some of these entities are both rare and lack cords and/or small nests of tumor cells (e.g., oncocytoma, acinic cell carcinoma, myoepithelioma) and, therefore, are not really a diagnostic dilemma. They will not be discussed further. The differential diagnoses also depend somewhat on location. For instance, sinonasal renal cell-like carcinoma would only be on the differential diagnosis for nasal tumors.

Table 1.

Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma (HCCC) and related mimics

| Feature | HCCC | MEC | EMC | CCMC | CEOT | CCOC | SCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical location | Predominant oral | 50 % oral 50 % major salivary | Predominant parotid | Predominant parotid | Jaw bone | Jaw bone | Mucosal all sites |

| Ductal structures | Rare (entrapped) in parotid | Rare | Prominent | Rare | Absent | Rare | Absent |

| Cysts | Rare | Common | Rare | Rare | Rare | Rare | Rare |

| Thin cords and small nests | Present | Rare | Rare | Rare | Present | Present | Common |

| Papillary Pattern | Absent | Absent | Focal | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Cribriform pattern | Focal | Absent | Common | Common | Absent | Focal | Basaloid variant |

| Stroma | Dual hyalinizing and fibrocellular | Absent or rarely hyalinizing | Absent or hyalinizing | Hyalinizing | Amyloid and hyalinizing | Dual hyalinizing and fibrocellular | Desmoplastic or hyalinizing |

| Spindled pattern | Absent | Absent | Common | Absent | Absent | Absent | Sarcomatoid variant |

| Perineural invasion | Common | Rare | Common | Not described | Rare | Common | Common |

| Mucosal involvement | Common | Common | Absent | Absent | Absent | Common | Common |

| Mucin | Common mostly as single cells | Common goblet type cells lining cysts and forming clusters | Absent | Absent | Absent | Common mostly as single cells | Rare |

| Amyloid (Congo red) | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Present | Negative | Negative |

| P63, HMWK | Positive | Positive | Abluminal cells positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| S100, actin, calponin | Negative | Negative | Abluminal cells positive | Positive | Absent | Absent | Sarcomatoid variant |

| Molecular markers | EWSR1-ATF1 | CRTC1-MAML2 | None | None | None | EWSR1-ATF1 | None |

HCCC hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma, MEC mucoepidermoid carcinoma, EMC epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, CCMC clear cell myoepithelial carcinoma, CEOT clear cell calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor, CCOC clear cell odontogenic carcinoma, SCC squamous cell carcinoma HMWK high molecular weight cytokeratins

Other Tumors That Share Squamous Differentiation with HCCC

Since HCCC shows squamous features by immunohistochemistry, the most likely differential diagnosis will be with SCC and “mucin-depleted” mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC). Contrary to previous reports [1], the presence of mucin-containing cells on H&E or by mucicarmine, irrespective of numbers, does not exclude HCCC [9]. MEC is distinguished by a greater tendency for cyst formation lined by goblet type mucinous cells, by solid growth of squamoid and intermediate cells, and by a general lack of sclerosis/hyalinization and small nests or thin cords of tumor. The latter feature is particularly unusual in MEC, while mucin-lined cysts do not occur in HCCC. In difficult cases or small biopsies, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for MAML2 and/or EWSR1 can be used to resolve this dilemma [9]. SCC, on the other hand, can have sclerosis and thin cords of tumor cells. The principle difference with SCC is with the invariable atypia and mitotic activity that is lacking in HCCC. Even in the most “well-differentiated” SCCs, there is always nuclear enlargement and usually ample mitotic figures. The presence of overlying mucosal dysplasia should also be a red flag against HCCC and in favour of SCC.

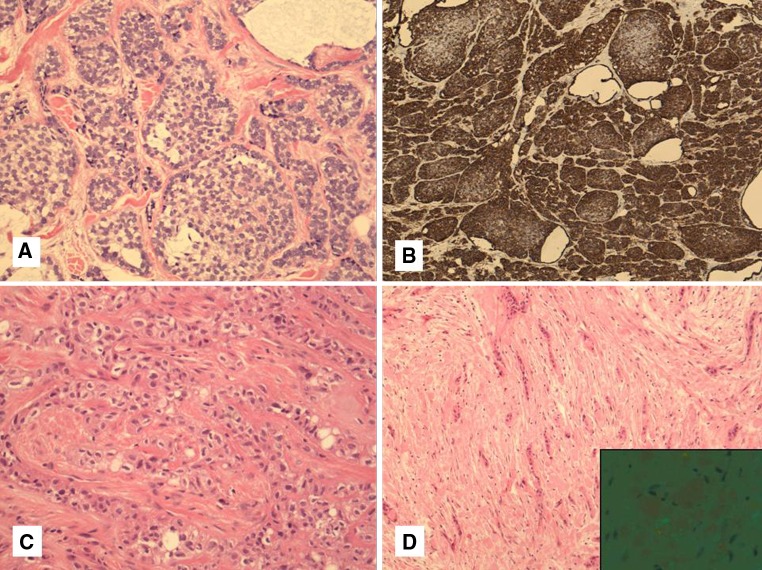

Tumor Mimics with Myoepithelial Differentiation

Although HCCC does not have myoepithelial differentiation when stained with actins and calponin, myoepithelial tumors do enter the differential diagnosis. Firstly, they share basal/squamous immunohistochemical positivity for p63 and high-molecular weight cytokeratins (HWMK). Secondly, the presence of myoepithelial marker positivity can be patchy or variable from case to case of true myoepithelial tumors. Finally, clear cell change is common in myoepithelial cells. Clear cell myoepithelial carcinoma is very rare with only few case reports and small series [16], so their nature is not well-described (Fig. 4a, b). Previous reports by Michal showed strong expression with S100 and actin in these tumors [16], which are lacking in HCCC [1]. In limited cases, there is also a lack of small thin cords in these tumors. The more common myoepithelial tumor that enters the differential diagnosis is epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (EMC), particularly when containing duct-poor myoepithelial overgrowth or conversely when an HCCC contains entrapped ducts. The latter occurs mostly in parotid HCCCs. In addition to lacking S100, actin and calponin staining, which are usually present in EMC, HCCC does not form papillary structures, is more common in the oral cavity in contrast to EMC, and generally shows smaller nuclei than EMC. HCCC also does not show spindling or oncocytic change which are often seen in EMC. Although adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC) does not usually show prominent clear cell change and virtually never has squamous differentiation, it can be mimicked by HCCCs when they contain prominent cribriform growth and perineural invasion. However, AdCC almost always has true duct formation, has angulated myoepithelial cell nuclei and is more atypical and mitotically active when showing solid growth. In our experience, HCCCs with prominent cribriform growth always have at least focal typical areas of clear cell nests and cords in a hyalinized stroma. It is, however, a potential diagnostic pitfall on a small biopsy.

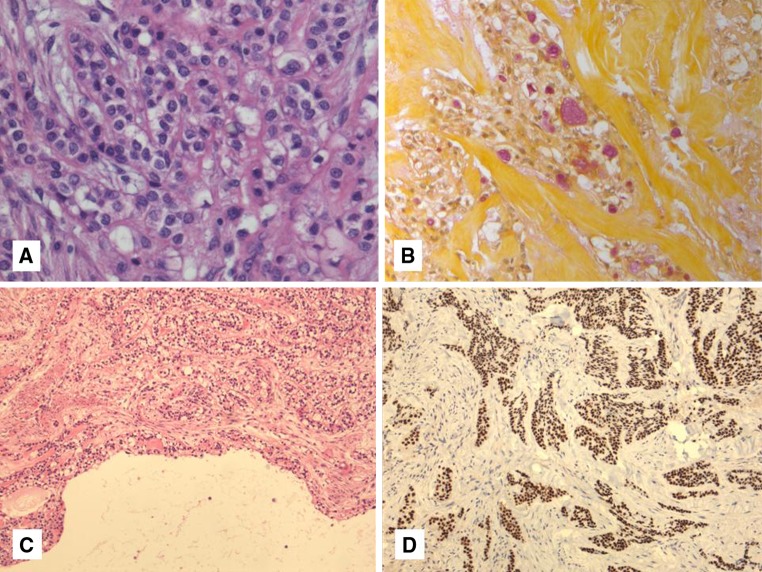

Fig. 4.

a–d Clear cell myoepithelial carcinoma shows a great degree of morphologic overlap with HCCC. It has common cribriform, solid and nested growth, hyalinization and clear cells (a). However, unlike HCCC it shows strong myoepithelial marker expression with S100 and actins (SMA shown here) (b). Another common mimic includes clear cell calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor (CEOT). This tumor can show a similar cordlike growth pattern and hyalinized background (c). However the background is made up of amyloid rather than collagen which can also be seen within tumor cells (d). Polarization microscopy showing typical apple-green birefringence (inset). This slide is courtesy of Dr. R. Seethala, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Tumors Arising Primarily in Jaw Bones with or Without Mucosal Involvement

Tumors of odontogenic origin that can show clear cell change are many and two in particular that overlap with HCCC are “clear cell odontogenic carcinoma” (CCOC) and “clear cell calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor” (CEOT), also known as “Pindborg tumor” [3]. These odontogenic neoplasms may be confused with either mucosal HCCC showing bone invasion, which is present in about 17 % of cases [9], or with primary “central” HCCC [11]. CCOC will be discussed below with molecular findings. CEOT usually shows a squamoid eosinophilic neoplasm with intercellular bridges, calcification and a hyalinized background containing amyloid, with some tumor cells containing amyloid as well [3]. Most tumors have solid areas but areas with only small nests of tumor within a mostly amyloid-containing stroma may be seen. Focal clear cell change is also not uncommon. Occasional cases of CEOT show prominent clear cell change (Fig. 4c, d). Recently, Bilodeau et al. [10] showed two cases of CEOT, initially called CCOC, which were very hypocellular and stroma-predominant. Both of these tumors contained amyloid, as shown by Congo red, and lacked EWSR1 rearrangement [10], clearly separating it from HCCC. Clues to the diagnosis of CEOT over central HCCC are that they show greater nuclear irregularities and nuclear enlargement in a portion of the tumor cells, as opposed to the bland uniform nuclei of HCCC. In addition, the amyloid shows a more granular quality with the typical “cracking” artifact that is lacking in the more sclerotic collagenous stroma that defines the hyalinization of HCCC.

Metastases

Finally, metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is always included in the differential diagnosis in every publication broaching the clear cell salivary differential diagnosis [1, 14]. However, the similarity with HCCC is minimal and the inclusion is over-stated in this author’s opinion. RCC is considerably more vascular and is generally either solid in growth or has a “crowded nested pattern”. The nuclei are larger and more atypical than HCCC, there is never squamous differentiation, and the dual stroma of HCCC is lacking. In addition, RCC never expresses p63 [17], which is almost always expressed in HCCC [9].

Molecular Findings in HCCC and Related Entities

Recently, rearrangements of the EWSR1 gene have been identified in 45 % of “soft tissue myoepithelial tumors” (SMET) [18]. SMET is a somewhat morphologically heterogeneous group of tumors with benign and malignant variants. Some are identical to their salivary counterparts and may show PLAG1 rearrangement [19] but these are not the tumors with EWSR1 rearrangement. The EWSR1 rearranged SMETs are distinct from myoepithelial tumors of salivary gland [18] and typically stain with S100 and/or GFAP, as well as keratins and/or EMA. Of the tumors with EWSR1 rearrangements by FISH, a subset has been shown to carry a EWSR1-ZNF444, EWSR1-PBX1 or EWSR1-POU5F1 fusion transcript, while the remainder have unknown gene partners [18]. Recently, a single case of a EWSR1-ATF1 positive SMET has also been described [20]. We noticed a distinct similarity between HCCC clear cell nests and stromal hyalinization and similar features in some cases of SMET, particularly those with a EWSR1-POU5F1 fusion transcript [18]. In order to examine the relationship between HCCC and SMET, we examined 23 of these cases by FISH for EWSR1. We also examined HCCC for MAML2 rearrangements to help distinguish mucinous HCCC from MEC. We found no MAML2 abnormalities in HCCC but demonstrated that 82 % of HCCC carry a EWSR1 rearrangement by FISH [9] (Fig. 5). No rearrangement of PBX1, ZNF444 or POU5F1 was found, however, suggesting that HCCC is not a salivary equivalent of SMET.

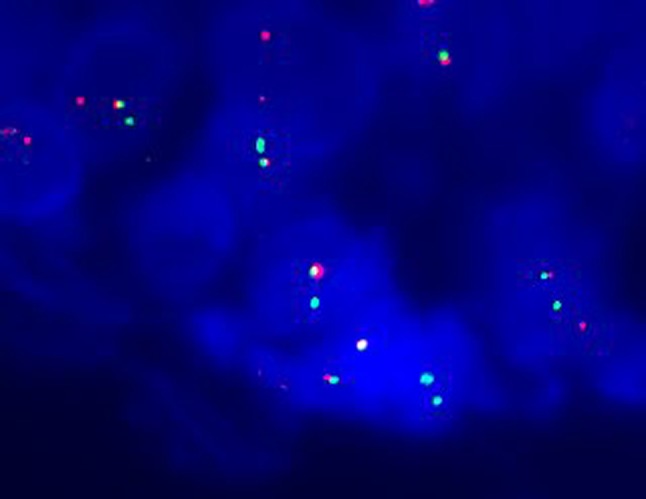

Fig. 5.

FISH for EWSR1 is becoming a very useful marker for salivary gland tumors with focal or diffuse clear cell differentiation, especially for small biopsies. This positive case shows one normal fused yellow signal and one break-apart signal per cell denoting rearrangement of the EWSR1 gene. The break-apart probe shows one separate green and red signal per cell

Subsequent examination of two tumors with rapid amplification of complimentary DNA ends (3′ RACE) showed an in-frame fusion between EWSR1 exon 11 and ATF1 exon 3 [9]. The resulting fusion product EWSR1-ATF1 was confirmed by RT-PCR and direct sequencing in these cases. Analysis of the remainder of our cohort showed that 93 % of EWSR1 rearranged HCCC cases also had ATF1 rearrangement, making this a consistent finding. The fusion genes involved are identical to those found in clear cell sarcoma and angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma; however, the exons involved are different, with most of these other tumors showing EWSR1 exons 7, 8, or 10 fused to ATF1 exons 4, 5, or 7 [21]. The EWSR1-ATF1 fusion in HCCC is also different than the one reported SMET by Flucke et al. [20]. We have subsequently used EWSR1 FISH in about a dozen new cases of HCCC, including some with unusual features and all have been positive. This is a useful diagnostic tool in the differential diagnosis of clear cell and other salivary tumors, since all other primary salivary neoplasms tested have been negative for this finding [9, 22].

Recently, Bilodeau et al. [10] examined clear cell odontogenic carcinoma (CCOC) and HCCC for EWSR1 rearrangement, having already previously concluded that these two tumors had extensive morphologic and immunohistochemical overlap [8]. A EWSR1 rearrangement was found in 11/12 (92 %) HCCCs and 5/8 (63 %) CCOCs [10]. Subsequent re-examination of 2 of these CCOCs showed a Congo red positive amyloid background, suggesting that these were hypocellular examples of CEOTs rather than CCOC, which increased the rate of EWSR1 FISH positivity to 5/6 (83 %) of the CCOC cases. In retrospect, one of the four EWSR1 negative HCCCs from our original manuscript was an example of a hypocellular CEOT arising in the maxilla and involving the gingival mucosa. It showed an amyloid rather than collagenous hyalinized background in contrast to the usual stromal features of HCCC. The overlap between HCCC and CCOC was further confirmed by Bilodeau et al. in one case of CCOC where ATF1 FISH positivity was found in addition to the EWSR1 positivity [10]. This can be regarded as evidence that either CCOC represents a central example of HCCC or that CCOC represents an “odontogenic analogue” to HCCC. Direct development from odontogenic rests has not been demonstrated thus far in a CCOC. This is ultimately a semantic argument and these two tumors are obviously highly-related (or identical) and different from CEOT.

Proposed Line of Differentiation and Issues with Nomenclature

HCCC has been known by several names including clear cell carcinoma of salivary gland, clear cell carcinoma, “not otherwise specified” (NOS) [3], hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma [1], and clear cell adenocarcinoma [2]. It is regarded as arising from salivary or seromucous glands in the upper aero digestive tract. The designation of adenocarcinoma has been used despite the fact that most publications did not allow for much duct formation and the presence of mucin was a diagnosis of exclusion [1, 3]. This designation may be because of the presumed salivary gland origin, and excluding mucinous differentiation was a convenient criterion in the differential diagnosis with MEC. Milchgrub et al. and the WHO also quote the ultrastructural findings as showing evidence of glandular differentiation despite tonofilaments, desmosomes and cytoplasmic glycogen [1, 3, 12]; all more in keeping with squamous differentiation and with the morphologic appearance and overlap with MEC. This was first highlighted by Dardick, who reviewed the original ultrastructural images and concluded that HCCC is a squamous lesion [7]. This is not surprising, not only because of the ultrastructural findings but also because of the original description of the tumor being HMWK positive [1] and subsequent descriptions of diffuse p63 positivity [8]. We have recently confirmed this and shown that HCCC routinely connects to the surface epithelium. The designation of HCCC as a squamous lesion and the connection to the surface mucosa, suggests that HCCC may in fact be a mucosal epithelium-derived neoplasm. This is somewhat at odds with the occasional origin in major salivary gland and the now-accepted presence of mucin in almost half of all cases [9]. The combination of squamous and mucinous differentiation could also be evidence that HCCC is a low-grade sclerosing adenosquamous carcinoma. In any event, in this author’s opinion, the use of the term “clear cell adenocarcinoma” is inappropriate as glandular differentiation is a minor or absent component compared with the consistent squamous differentiation.

It is now generally accepted that many neoplasms pursue a line of differentiation rather than arising from a specific cell type and they do not have to resemble the tissue of origin at all. This is particularly true in soft tissue where numerous entities have no obvious line of differentiation and many of these are associated with a specific translocation. HCCC is another example of a translocation-driven tumor that does not specifically resemble its tissue of origin. The presence of typical and reproducible morphologic features coupled with a specific EWSR1-ATF1 translocation also argues against the designation “clear cell carcinoma, NOS”, since this implies a diagnosis of exclusion or “waste basket” category. HCCC is a specific neoplasm and deserves to be regarded as such. If there are clear cell carcinomas that don’t fit into HCCC or other known entities (including some in my experience with complete solid growth), it remains to be seen what these should be called or whether an “NOS” category should persist outside of HCCC.

Grading, Treatment and Prognosis

There is no formal grading system and HCCC is considered low-grade by definition [3]. However, we have recently seen several cases that have had focal or significant necrosis (personal observation). One of these was recently reported as a HCCC with high-grade transformation (dedifferentiation) [23] and some cases have shown basaloid morphology [9]. Of these basaloid cases, two have shown EWSR1 rearrangement by FISH while a third recent case was not tested. The two cases with rearrangement did not show significant mitotic figures; however, one showed higher-grade nuclear features. We have also recently seen a biopsy of a large HCCC in the neck with no apparent primary and showing radiologic evidence of distant metastases. This was regarded as a likely ectopic salivary gland origin but a regression of a primary intraoral tumor with neck metastasis could not be excluded at the time. The case numbers and number of poor outcomes are not sufficient at this time to suggest that grading is necessary and certainly not a specific grading system. However, we still regard cases with necrosis, high mitotic indices, and significant pleomorphism to be high-grade for the purposes of a diagnostic report.

The vast majority of HCCC have had good outcome. Only one documented mortality due to disease has been described [24], although an additional “palliative” case has been reported [22]. The tumors have a propensity for locoregional recurrence in the order of 12–17 % [9, 15, 23] and occasional lymph node [1] or distant metastases [15] have been noted. Solar et al. reported a 25 % lymph node positivity rate in a review of reported cases [5]; however, this is in sharp contrast to our large series which found no lymph node or distant metastases with reasonable follow-up (mean 48 months) [9]. In any event, the overall prognosis is still excellent in these latter cases. Treatment usually involves primary resection if the tumor arises in an amenable location. Tongue base tumors may have primary radiation due to morbidity of resection. Many cases have post operative radiotherapy; however, there is no standard of care for these tumors as they are rare and respond well in most instances irrespective of treatment.

Conclusions

Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma is a unique low grade salivary gland tumor that shows nests, cords and trabeculae of clear and eosinophilic cells in a characteristic hyalinized stroma [1]. It primarily arises in the oral cavity but has been described at essentially all salivary gland and seromucous gland sites [5]. The tumors raise a broad differential diagnosis, most of which are easily distinguished by light microscopy and immunohistochemistry. HCCC demonstrates a squamous line of differentiation without true myoepithelial marker expression [1]. HCCC has an excellent overall behavior although a growing number of cases are showing high-grade features [23] or unusual behavior (personal observations). There is no rationale at this time for a grading system. Mucinous differentiation, irrespective of quantity is not an exclusion criterion and should not lead to a diagnosis of clear cell mucoepidermoid carcinoma [9]. Recent evidence shows that this carcinoma harbors a recurrent and consistent EWSR1-ATF1 fusion, which also helps link this tumor to “clear cell odontogenic carcinoma” [9, 10]. It also serves as a useful diagnostic marker in difficult cases or small biopsies. The use of the terms “(hyalinizing) clear cell adenocarcinoma” or “clear cell carcinoma, (NOS)” are inappropriate and should be discouraged owing to the unequivocal squamous features and presence of a consistent genetic alteration in the vast majority of cases.

References

- 1.Milchgrub S, Gnepp DR, Vuitch F, Delgado R, Albores-Saavedra J. Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma of salivary gland. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(1):74–82. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis GL, Auclair PL (Editors): Armed forces Institute of pathology (AFIP) atlas of tumor pathology. Tumors of the salivary glands (fourth series, fascicle 9). Maryland: ARP Press; 2008. p 301–309.

- 3.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, et al., editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours. pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Sullivan-Mejia ED, Massey HD, Faquin WC, Powers CN. Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma: report of eight cases and a review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3(3):179–185. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0124-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solar AA, Schmidt BL, Jordan RC. Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma: case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Cancer. 2009;115(1):75–83. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang S, Zhang J, Chen X, Wang L, Xie F. Clear cell carcinoma, not otherwise specified, of salivary glands: a clinicopathologic study of 4 cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(5):712–720. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dardick I, Leong I. Clear cell carcinoma: review of its histomorphogenesis and classification as a squamous cell lesion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(3):399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bilodeau EA, Hoschar AP, Barnes EL, Hunt JL, Seethala RR. Clear cell carcinoma and clear cell odontogenic carcinoma: a comparative clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;5(2):101–107. doi: 10.1007/s12105-011-0244-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonescu CR, Katabi N, Zhang L, Sung YS, Seethala RR, Jordan RC, Perez-Ordoñez B, Have C, Asa SL, Leong IT, Bradley G, Klieb H, Weinreb I. EWSR1-ATF1 fusion is a novel and consistent finding in hyalinizing clear-cell carcinoma of salivary gland. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50(7):559–570. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilodeau EA, Weinreb I, Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Dacic S, Muller S, Barker B, Seethala RR. Clear cell dontogenic carcinomas show EWSR1 rearrangements: a novel finding and biologic link to salivary clear cell carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2012; 25(Supplement 2s) 101: 305A. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Berho M, Huvos AG. Central hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma of the mandible and the maxilla a clinicopathologic study of two cases with an analysis of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(1):101–105. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Félix A, Rosa JC, Nunes JF, Fonseca I, Cidadão A, Soares J. Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma of salivary glands: a study of extracellular matrix. Oral Oncol. 2002;38(4):364–368. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(01)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezende RB, Drachenberg CB, Kumar D, Blanchaert R, Ord RA, Ioffe OB, Papadimitriou JC. Differential diagnosis between monomorphic clear cell adenocarcinoma of salivary glands and renal (clear) cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(12):1532–1538. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199912000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber B, Côté D, Seikaly H. Clearing up clear cell tumours of the head and neck: differentiation of hyalinizing and odontogenic varieties. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39(5):E56–E60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang B, Brandwein M, Gordon R, Robinson R, Urken M, Zarbo RJ. Primary salivary clear cell tumors—a diagnostic approach: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 20 patients with clear cell carcinoma, clear cell myoepithelial carcinoma, and epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126(6):676–685. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0676-PSCCTA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michal M, Skálová A, Simpson RH, Rychterová V, Leivo I. Clear cell malignant myoepithelioma of the salivary glands. Histopathology. 1996;28(4):309–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHugh JB, Hoschar AP, Dvorakova M, Parwani AV, Barnes EL, Seethala RR. p63 immunohistochemistry differentiates salivary gland oncocytoma and oncocytic carcinoma from metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1(2):123–131. doi: 10.1007/s12105-007-0031-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Chang NE, Pawel BR, Travis W, Katabi N, Edelman M, Rosenberg AE, Nielsen GP, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. EWSR1-POU5F1 fusion in soft tissue myoepithelial tumors. A molecular analysis of sixty-six cases, including soft tissue, bone, and visceral lesions, showing common involvement of the EWSR1 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49(12):1114–1124. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahrami A, Dalton JD, Krane JF, Fletcher CD. A subset of cutaneous and soft tissue mixed tumors are genetically linked to their salivary gland counterpart. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51(2):140–148. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flucke U, Mentzel T, Verdijk MA, Slootweg PJ, Creytens DH, Suurmeijer AJ, Tops BB. EWSR1-ATF1 chimeric transcript in a myoepithelial tumor of soft tissue: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2012;43(5):764–768. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang WL, Mayordomo E, Zhang W, Hernandez VS, Tuvin D, Garcia L, Lev DC, Lazar AJ, López-Terrada D. Detection and characterization of EWSR1/ATF1 and EWSR1/CREB1 chimeric transcripts in clear cell sarcoma (melanoma of soft parts) Mod Pathol. 2009;22(9):1201–1209. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah AA, LeGallo RD, van Zante A, Frierson Jr. HF, Mills SE, Berean KW, Mentrikoski MJ, Stelow EB. EWSR1 Genetic rearrangements in salivary gland tumors: a specific and very common feature of hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(4):571–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Jin R, Craddock KJ, Irish JC, Perez-Ordonez B, Weinreb I. Recurrent hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma of the base of tongue with high-grade transformation and ewsr1 gene rearrangement by fish. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(3):389–394. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0338-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Regan E, Shandilya M, Gnepp DR, Timon C, Toner M. Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma of salivary gland: an aggressive variant. Oral Oncol. 2004;40(3):348–352. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]