Abstract

Autochthonous human gnathostomiasis had never been reported in the Republic of Korea. We report here a case of Gnathostoma spinigerum infection in a 32-year-old Korean woman, presumed to have been infected via an indigenous route. The patient had experienced a painful migratory swelling near the left nasolabial fold area of the face for a year, with movement of the swelling to the mucosal area of the upper lip 2 weeks before surgical removal of the lesion. Histopathological examinations of the extracted tissue revealed inflammation with heavy eosinophilic infiltrations and sections of a nematode suggestive of a Gnathostoma sp. larva. The larva characteristically revealed about 25 intestinal cells with multiple (3-6) nuclei in each intestinal cell consistent with the 3rd-stage larva of G. spinigerum. The patient did not have any special history of travel abroad except a recent trip, 4 months before surgery, to China where she ate only cooked food. The patient is the first recorded autochthonous case of G. spinigerum infection in Korea.

Keywords: Gnathostoma spinigerum, gnathostomiasis, case report, lip

INTRODUCTION

Gnathostoma spp. are nematodes that are parasitic in the stomach, esophagus, and kidneys of carnivorous mammals including the tiger, opossum, pig, wild boar, weasel, racoon, otter, and rat [1]. Humans are an accidental host, and the worms do not reach maturity but stay at their larval stages and migrate through the subcutaneous tissues, muscles, and visceral organs including the brain [1,2]. The infection is contracted by ingestion of raw or inadequately cooked freshwater fish or other intermediate or transport hosts, such as chickens, snails, frogs, or pigs that contain the infective third-stage larvae [3,4].

At least 13 valid species of Gnathostoma have been reported [4]. Among them, 6 species are currently known to infect humans; Gnathostoma spinigerum, Gnathostoma doloresi, Gnathostoma nipponicum, Gnathostoma hispidum, Gnathostoma malaysiae, and Gnathostoma binucleatum [4,5]. The first 5 occur mainly in Asia and the last species is found in Latin America [4]. In Asia, G. spinigerum is the most common cause of human gnathostomiasis [6]. The first case of human gnathostomiasis was reported in 1889 in a Thai woman presenting with breast abscess [3]. Since then, considerable numbers of patients have been described in Thailand, Japan, China, India, and Myanmar [1,3,4,6]. The importance of gnathostomiasis as an emerging imported disease in many countries has been highlighted [7]. It is also of note that the geographical distribution of Gnathostoma, in particular, G. spinigerum, seems to be expanding, even to African countries, since 2 British tourists to Botswana who had never traveled to endemic areas in Asia were found to be infected with G. spinigerum [8].

In Korea, the life cycle of G. spinigerum [9], G. nipponicum [10-12], and G. hispidum [13] has been documented with recovery of larval and adult worms in intermediate and/or definitive hosts. However, human autochthonous infection with Gnathostoma sp. has never been reported, while several reports were published on imported G. spinigerum [14,15], G. hispidum [16], and possible G. nipponicum infection cases [17], and an outbreak of G. spinigerum infection among 38 Korean emigrants residing in Myanmar [18]. We recently encountered an interesting case of G. spinigerum infection in a patient who never visited any endemic area of gnathostomiasis before the onset of the disease. Here, we report the patient as the first autochthonous gnathostomiasis case in Korea.

CASE RECORD

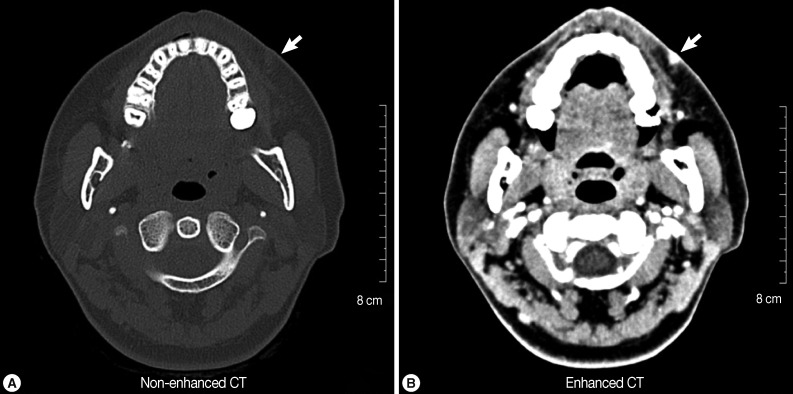

The patient was a 32-year-old Korean woman who was working as a cashier in a Korean restaurant in the suburb of Seoul, Republic of Korea. In August 2011, she sensed a small mass in her left nasolabial fold area of the face before being seen at the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Bundang Jesaeng General Hospital, Bundang, Korea. She experienced painful swelling and itching several times, with signs of migration, but there were no other symptoms, such as fever and chill. On physical examination, a small nodule about 1 cm in diameter was noted. At that time, she did not receive any special treatment for the mass. In August 2012, she had CT scans (non-enhanced and enhanced) on the soft tissues of the left nasolabial fold area, where a small mass with high density was recognized on the external side (Fig. 1A, B). Two weeks later, the swelling had moved slightly to the mucosal area of the upper lip, and we decided to surgically remove the lesion in September 2012. Serological tests were performed to check for 4 kinds of anti-parasitic antibodies (Clonorchis sinensis, sparganum, cysticercus, and Paragonimus westermani) with negative results.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scans (A: non-enhanced; B: enhanced) of the patient showing a small soft tissue mass (arrow) with mild fatty infiltration on the external area of the left nasolabial fold. The lesion migrated slightly to the mucosal side of the upper lip after the CT scan examination and surgery was performed on the lesion.

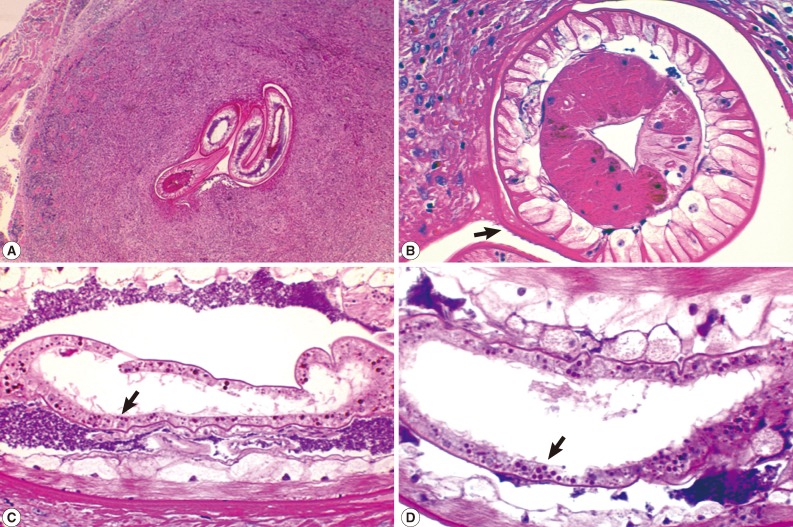

The resected small nodule (0.4×0.3 cm) was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin immediately after removal and was processed for routine histopathological examinations. Briefly, the tissue sample was dehydrated in a graded series of ethanols, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at a thickness of approximately 3-4 µm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and observed by light microscopy. Histopathologically, the lesion revealed signs of chronic active inflammation heavily infiltrated with eosinophils. In the center of the inflammatory lesion, several sections of a nematode larva were observed (Fig. 2A-D). The larva was 0.20-0.25 mm in diameter, having polymyarian-coelomyarian somatic muscles (Fig. 2B), tegumental structures (Fig. 2B), including the cuticle, cuticular spines (arrow in Fig. 2B), and hypodermis, and lateral and ventral cords. The larva also revealed multinucleated (with 3-7 nuclei) intestinal epithelial cells (Fig. 2C, D) which is characteristic of G. spinigerum larva [19,20].

Fig. 2.

Sections of a Gnathostoma spinigerum larva found in the excised mass from the mucosal side of the left nasolabial fold. (A) Sections of the larva showing its anterior (right 2 sections) and posterior (left 1 section) parts (×40). (B) A cross section of an anterior part of the larva showing the cuticle (see cuticular spines; arrow), hypodermis, muscles, lateral cords, and intestine (×200). (C) Another section showing the morphology of the intestine and intestinal cells (arrow). There are approximately 25 intestinal cells, each with 3-7 nuclei (×200). (D) A close-up view of the intestine and intestinal cells; each cell has multiple (3-7) nuclei (arrow, ×250).

Her past history showed that she did not prefer raw fish or other undercooked food, and she seldom traveled abroad, with the only trip being a 2-week trip to Beijing, China in May 2012, about 9 months after the onset of the small mass. She recalled that she ate only cooked food during the trip. Therefore, the source of infection in this patient was unclear. In May 2011, she had a drainage treatment for periodontitis.

DISCUSSION

In Korea, the first report of Gnathostoma was the recovery of 2 larval worms of G. spinigerum in a snakehead fish in Kimhae City (near Pusan) in 1973 [9]. However, no further reports on G. spinigerum larvae in fish or other intermediate hosts have been available. Moreover, indigenous human infections with G. spinigerum or other Gnathostoma spp. had never been reported. Korea has been excluded from the list of countries with cases of gnathostomiasis [3]. However, in 1998, advanced 3rd-stage larvae of G. hispidum were detected in a pit-viper snake, Agkistrodon brevicaudus, purchased in Pusan [13]. In addition, in 2003 and 2011, advanced 3rd-stage larvae of G. nipponicum were detected in grass snakes (Rhabdophis tigrina) from Hongcheon-gun, Gangwon-do [10] and Jeju-do [12]. In 2011, adult G. nipponicum was discovered in the stomach of weasels in Jeju-do [11]. Therefore, Korea should be included among the countries where the life cycle of Gnathostoma spp. is indigenously maintained.

In the meantime, several imported human cases of G. spinigerum, G. hispidum, and Gnathostoma sp. (possible G. nipponicum) were reported in Korea [14-17], and an outbreak of G. spinigerum infection occurred among 38 Korean emigrants who consumed raw fish served in a restaurant in Myanmar [18]. However, indigenous human infections with Gnathostoma spp. had never been reported. Our patient had no history of travel abroad, particularly in endemic areas of gnathostomiasis, before the onset of her disease. Her only overseas travel was to China for 2 weeks in May 2012 when the presence of the disease was already notified for 9 months.

Therefore, we designated our patient as an autochthonous case of G. spinigerum infection. The species of parasite was G. spinigerum based on the characteristic morphology of the larva, particularly multinucleated (3-7 nuclei) intestinal cells, found in histological sections. However, the patient did not like to eat raw fish and other raw food. G. spinigerum larvae have not been detected in Korea after they were reported only one time in 1973 [9]. Therefore, the source of infection in this patient was uncertain.

G. spinigerum tends to remain in the subcutaneous tissues but it can also migrate to deeper tissues, where it may cause serious damage [3]. In our patient, the larva remained subcutaneously in the nasolabial fold area (it moved to the mucosal side of the upper lip). However, the location of the larva in our case was unique and a rare occasion according to available literature [3,7]. Some reported cases of ganthostomiasis involved the ear, nose, and throat, including a case simulating mastoiditis [3] and several cases that occurred in the soft palate [21], cheek [22], tip of the tongue [23], tympanic membrane [24], and gum [25]. However, lip involvement was never documented. Henceforth, in Korea, gnathostomiasis should be included among the list of differential diagnosis for small masses on the subcutaneous tissues, muscles, and internal organs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Prof. Katsuhiko Ando, Department of Medical Zoology, Mie University School of Medicine, Japan, and Prof. Yukifumi Nawa, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand, for their kindness in identifying the sectioned histopathological specimens of our patient.

References

- 1.Miyazaki I. An Illustrated Book of Helminthic Zoonoses. Fukuoka, Japan: International Medical Foundation of Japan; 1991. pp. 368–409. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katchanov J, Sawanyawisuth K, Chotmongkol V, Nawa Y. Neurognathostomiasis, a neglected parasitosis of the central nervous system. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1174–1180. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.101433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rusnak JM, Lucey DR. Clinical gnathostomiasis: case report and review of the English-language literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:33–50. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dekumyoy P, Yoonuan T, Waikagul J. Gnathostoma. In: Liu D, editor. Molecular Detection of Human Parasitic Pathogens. Boca Raton, London, New York: CRC Press, Taylor-Francis Group; 2013. pp. 563–570. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nomura Y, Nagakura K, Kagei N, Tsutsumi Y, Araki K, Sugawara M. Gnathostomiasis possibly caused by Gnathostoma malaysiae. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2000;25:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nawa Y. Historical review and current status of gnathostomiasis in Asia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1991;22(suppl):217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herman JS, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:484–492. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00003-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herman JS, Wall EC, van Tulleken C, Godfrey-Faussett P, Bailey RL, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis acquired by British tourists in Botswana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:594–597. doi: 10.3201/1504.081646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YK. A study on Gnathostoma (1) An investigation into the geographical distribution of larvae on the second-third stage in Gyeongsang Nam Do. Bull Pusan Nat Univ (Natur Sci) 1973;15:111–116. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han ET, Lee JH, Choi SY, Park JH, Shin EH, Chai JY. Surface ultrastructure of the advanced third-stage larvae of Gnathostoma nipponicum. J Parasitol. 2003;89:1245–1248. doi: 10.1645/GE-3232RN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woo HC, Oh HS, Cho SH, Na BK, Sohn WM. The Jeju weasel, Mustela siblica quelpartis, a new definitive host for Gnathostoma nipponicum Yamaguti, 1941. Korean J Parasitol. 2011;49:317–321. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2011.49.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woo HC, Oh HS, Cho SH, Na BK, Sohn WM. Discovery of larval Gnathostoma nipponicum in frogs and snakes from Jeju-do (Province), Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2011;49:445–448. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2011.49.4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sohn WM, Lee SH. The first discovery of larval Gnathostoma hispidum (Nematoda: Gnathostomidae) from a snak host, Agkistrodon brevicaudus. Korean J Parasitol. 1998;36:81–89. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1998.36.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Hong ST, Chai JY. Description of a male Gnathostoma spinigerum recovered from a Thai woman with meningoencephalitis. Korean J Parasitol. 1988;26:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SD, Lee HJ, Kim JW. A case of gnathostomiasis. Korean J Dermatol. 2001;39:1427–1429. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HS, Lee JJ, Joo M, Chang SH, Chi JG, Chai JY. Gnathostoma hispidum infection in a Korean man returning from China. Korean J Parasitol. 2010;48:259–261. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2010.48.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang JH, Kim M, Kim ES, Na BK, Yu SY, Kwak HW. Imported intraocular gnathostomiasis with subretinal tracks confirmed by western blot assay. Korean J Parasitol. 2012;50:73–78. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2012.50.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chai JY, Han ET, Shin EH, Park JH, Chu JP, Hirota M, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Nawa Y. An outbreak of gnathostomiasis among Korean emigrants in Myanmar. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akahane H, Sano M, Mako T. Morphological difference in cross sections of the advanced third-stage larvae of Gnathostoma spinigerum, G. hispidum and G. doloresi. Jpn J Parasitol. 1986;35:465–467. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ando K, Hatsushika R, Akahane H, Matsuoka H, Taylor D, Miura K, Chinzei Y. Gnathostoma nipponicum infection in the past human cases in Japan. Jpn J Parasitol. 1991;40:184–186. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daengsvang S. Human gnathostomiasis in Siam with reference to the method of prevention. J Parasitol. 1949;35:116–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prommas C, Daengsvang S. Nine cases of human gnathostomiasis. Ind Med Gaz. 1934;69:207–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srisawai P, Jongwutiwes S. Lingual gnathostomiasis: a case report. J Med Assoc Thai. 1988;71:285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuchavaree A, Supiyaphun P, Sitticharoenchai P, Suphanakorn S. A case of aural gnathostomiasis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1985;12:163–167. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(85)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Transurat P. Gnathostomiasis. J Med Assoc Thai. 1955;38:25–32. (in Thai) [Google Scholar]