Abstract

Measurements of cervical immunity are important for evaluating immune responses to infections of the cervix and to vaccines for preventing those infections. Three ophthalmic sponges, Weck-Cel, Ultracell, and Merocel, were loaded in vitro with interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), immunoglobulin A (IgA), or IgG, and sponges were extracted and evaluated for total recovery by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). There was excellent (>75%) recovery for all immune markers from all three devices except for IL-6, which was poorly recovered (<60%) for all sponge types, IFN-γ, which was poorly recovered from both Weck-Cel and Ultracell sponges but was completely recovered from Merocel sponges, and IL-4, which was poorly recovered from Weck-Cel sponges but was completely recovered from Ultracell or Merocel sponges. We then compared the absolute recovery of selected markers (IL-10, IL-12, IgG, and IgA) from cervical secretion specimens collected from women using each type of sponge. There were no significant differences in the recoveries of IL-10, IL-12, and IgG from cervical specimens collected by any type of ophthalmic sponge, but there was reduced IgA recovery from Merocel sponges. However, the variability in these measurements attributable to sponge types (1 to 3%) was much less than was attributable to individuals (45 to 72%), suggesting that differences in sponge type contribute only in a minor way to these measurements. We infer from our data that the three collection devices are adequate for the measurements of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-5, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, and IgG. Merocel may be a better ophthalmic sponge for the collection of cervical secretions and measurements of IL-4, IL-8, IL-10, GM-CSF, and IFN-γ, but our data from clinical specimens, not in vitro-loaded sponges, suggested the possibility of reduced recovery of IgA. These findings require confirmation.

We have been interested in optimizing the collection of cervical secretions by using ophthalmic sponges to evaluate cervical immunity in the context of host response to and vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection (3-5, 7, 8, 11-13, 15). The measurement of immunity at the cervix may be necessary to understand immune responses to HPV, given the localized nature of infection and the poor correlation between levels of immunity in blood and cervical secretions (3, 4). There are numerous methods for sampling genital tract secretions, including such methods as cervicovaginal lavage and passive absorption. However, unlike cervicovaginal lavages that represent an admixture of secretions of the cervix and vagina, possibly two immunologically distinct anatomical sites (6, 14), this method, like Sno-Strips wicks (Akron, Abita Springs, La.) (19), collects undiluted cervical secretions. Previously, we have shown that the collection of cervical secretions by using a Weck-Cel (XOMED Surgical Products, Inc., Jacksonville, Fla.) ophthalmic sponge was a minimally invasive and broadly useful method of specimen collection that did not negatively impact the performance of Pap smears for the detection of cytologic abnormalities (11). We have also demonstrated that cytokine and immunoglobulin (Ig) measurements from cervical secretions collected by these devices are reproducible (9). We have successfully implemented these collections in our large cohort study since 1996 (2). However, a recent study to optimize recovery of immune markers from Weck-Cel sponges demonstrated that some immune markers, such as interleukin-4 (IL-4) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), were poorly recovered from in vitro loading of these sponges (16). The reason for poor recovery of these cytokines is uncertain, but one possible explanation is that specific immune markers irreversibly bind to the absorbent material of this sponge.

To address whether the composition of the sponge might improve the accuracy of measuring immune markers in cervical secretions, we compared the recoveries of immune markers from Weck-Cel ophthalmic sponges (composed of cellulose), Ultracell (Ultracell Medical Technologies, North Stonington, Conn.) ophthalmic sponges (composed of polyvinyl alcohol), and Merocel (XOMED Surgical Products, Inc.) ophthalmic sponges (composed of hydroxylated polyvinyl acetate) loaded in vitro and in vivo. For our in vitro investigations, we selected a broad spectrum of immune biomarkers to load onto the sponges that represent T-cell helper 1 (Th1) and 2 (Th2) responses and included the aforementioned problematic cytokines, IL-4 and IFN-γ. For our in vivo investigations, the number of markers we can explore from a sponge is limited; we thus selected IgA and IgG recovery from sponges loaded with cervical secretions to identify the optimal sponge for our vaccine work as well as two representative cytokines, IL-10 and IL-12, that we typically measure in cervical secretions from our natural history studies of HPV (7, 12).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro loading of ophthalmic sponges.

Sponges were loaded with immune marker standards, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IFN-γ, or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, from commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (BioSource International, Camarillo, Calif.) or with commercially available IgG and IgA (The Binding Site, Birmingham, United Kingdom). The lyophilized standards were reconstituted with the diluent provided with the kit. The standard was then further diluted so that 100 μl of the diluted immune marker absorbed by sponges would have a final concentration in the extraction volume equal to the median of the standard curve if 100% of the material was recovered. For each immune marker, five spears of each type were spiked with diluted immune marker, allowed to absorb for 10 min, and then extracted. As a background control, an additional spear was loaded with extraction buffer alone (no immune marker) and tested, and the resulting value was subtracted from test values. As a positive control, a volume of the diluted immune marker was added directly to the extraction buffer and tested, and the result was compared to the expected 100% value. All ELISAs were run on the same day the spears were extracted to minimize degradation of the immune marker. All samples were run in duplicate in the ELISAs, and the average of these two values was used.

Extraction of ophthalmic sponges.

Sponges were extracted according to a previously described protocol (16). Briefly, each sponge was weighed to estimate the volume of secretions absorbed onto the sponge. The sponge was then equilibrated in 300 μl of extraction buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, 0.25 M NaCl, 0.1 mg of aprotinin per ml, and 0.001% sodium azide) for 30 min at 4°C. Sponges were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g in a Spin-x centrifuge filter unit (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) to separate extracted samples from the sponge matrix. A second wash of the sponge with 300 μl of extraction buffer was followed by immediate centrifugation in the Spin-X tube. The two extraction volumes were combined, 5 μl was removed for hemoglobin testing by Hemastix (VWR International, West Chester, Pa.), and then 4 μl of fetal calf serum was added to the remaining specimen. A dilution factor was calculated based on the estimated volume and dry weight of the spear as previously described (8): [(x − y) + 0.6 g of buffer]/(x − y), where x equals the weight of the sponge after collection and y is the mean weight of the dry spear, based on independently weighing six spears.

Collection and testing of clinical specimens.

Cervical secretions were collected from 90 consenting women scheduled for a colposcopy in the context of an National Cancer Institute (NCI)-sponsored, NCI- and local institutional review board-approved population-based cohort study of HPV and cervical neoplasia established in Guanacaste, Costa Rica, from 1993 to 1994 (9, 10). Women were scheduled for colposcopy examinations either for (i) an exiting colposcopic inspection as a participant in the natural history study; (ii) a follow-up visit after the exit colposcopy; (iii) an evaluation and, if necessary, treatment of high-grade cervical neoplasia; or (iv) a follow-up visit after a loop electrosurgical excision procedure of the transformation zone to treat high-grade cervical neoplastic lesions. Specimens were collected every day from the first 10 consenting women attending their colposcopic appointment plus all women with indications of high-grade cervical neoplasia or from women from whom we had originally collected cervical secretions until 90 participants were accrued. Participants were randomly assigned one of six combinations of paired sponges (Merocel-Weck-Cel, Merocel-Ultracell, Ultracell-Merocel, Ultracell-Weck-Cel, Weck-Cel-Merocel, and Weck-Cel-Ultracell). Cervical secretions were collected as paired specimens as previously described (12). Specimens were collected by a single practitioner (L. A. Morera) by placing the sponge portion of the ophthalmic device within the os of the cervix for 30 seconds, removing the device from the patient, and immediately placing it into a cryovial and into liquid nitrogen. The second specimen was collected in a similar manner. Since we began collecting cervical secretions in 1996, these collections have been well tolerated, with no reports of adverse events or noncompliance, and the same was true for the three devices evaluated in this study.

The same commercial ELISA kits used to assay the in vitro-loaded sponges were used to assay extracted clinical specimens for IL-2, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ, IgG, and IgA. Specimens, extracted in the same fashion as the in vitro-loaded sponges, were tested for IL-2, IFN-γ, IgG, and IgA by using undiluted volumes of 200 μl, 200 μl, 10 μl (diluted 1:1,000), and 10 μl (diluted 1:1,000), respectively. Specimens were tested for IL-10 and IL-12 by using 80-μl volumes diluted 1:1.5 with the assay diluent. We did not evaluate IL-4 or the other immune markers primarily because of the limited number of markers that could be measured from a single specimen and the need to test whether IL-10, IL-12, IgG, and IgA, our standard markers of Th1 and Th2 responses, were recovered equally well from the three sponge types.

Analysis.

Total amounts of immune markers recovered from in vitro-loaded sponges were calculated by multiplying the final extracted volumes and the concentrations from the ELISA. The total amount recovered was divided by the total amount loaded onto the sponge to calculate the mean percent recovery and 95% confidence interval. Differences in percent recovery between sponges were tested for statistical significance by a Z test.

To assess the randomization of women into the six study groups, we evaluated the differences between groups for a small number of sociodemographic, reproductive, and sexual variables (age at visit, use of oral contraceptives, lifetime number of pregnancies [<4 or ≥4], years of education, age at first pregnancy, and age at first sexual intercourse) collected through an interviewer-administered questionnaire. Statistical differences in median values for continuous variables and in categorical variables were assessed by a Kruskal-Wallis test, a nonparametric analysis of variance statistic, and a Pearson χ2 test, respectively.

The measurements of the concentrations of immune markers extracted from each type of ophthalmic sponge were corrected for dilution as the result of extraction and compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test. First and second sponges were evaluated separately and then combined in a separate analysis. For the analysis of IL-10 and IL-12 concentrations, specimens with values below the limits of detection (0.2 pg/ml for IL-10 and 0.8 pg/ml for IL-12) were assigned a value of one-half the limit of detection (14 first sponges and 16 second sponges for IL-10; 2 first sponges and 1 second sponge for IL-12). Only three first spears and seven second spears had detectable levels of IFN-γ (limit of detection, 4 pg/ml), and all IL-2 measures were below the limits of detection (5 pg/ml). Therefore, neither immune marker could be evaluated from cervical secretions, and only IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-12 levels in cervical secretions were evaluated.

Variance component analyses using mixed models (random and fixed effects) were performed (12, 17, 18) to explore the relationships of covariates with the levels of the IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-12 in cervical secretions. The type of sponge (Merocel, Ultracell, or Weck-Cel), the order of collection (first or second sponge), the volume of the secretions (quartile categories of <14.5, 14.5 to 22.8, 22.9 to 43.4, and ≥43.5 μl), and the level of hemoglobin in the secretions (categories of 1 to 4, 5 to 6, and 7, as measured by the Hemastix) were treated as fixed effects. The individuals in the study were treated as random effects. Boxcox transformations [Y = (yλ − 1)/λ, in which y is the measured value and λ is the Boxcox coefficient] (1) of IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-12 concentrations were used to normalize the data (NB, logarithmic transformation was not sufficient to create a normal distribution of values); values of λ for IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-12 were 0.0606572, 0.0921632, 0.1238986, and 0.1822423, respectively. In univariate analyses, hemoglobin levels were not associated with any of these immune markers and, thus, were excluded from additional analyses. To estimate the relative contribution of variance from individuals versus the type of the sponge, a model was run in which sponge type was also treated as a random effect. Adjusted means were calculated on transformed values by using the least squared means command of the SAS/STAT software (version 8; SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), and the values were untransformed. In multivariate models, education and age did not appreciably alter the estimates of adjusted mean concentrations of the immune markers and thus were excluded from the final models.

Finally, to examine the relative performance and determine if there were systematic errors associated with any sponge type, we examined the correlation of measurements from the first sponge and the combination of both second sponges (e.g., a Merocel first sponge versus an Ultracell or Weck-Cel second sponge) by using scatter plots and calculating Spearman correlations (ρ).

RESULTS

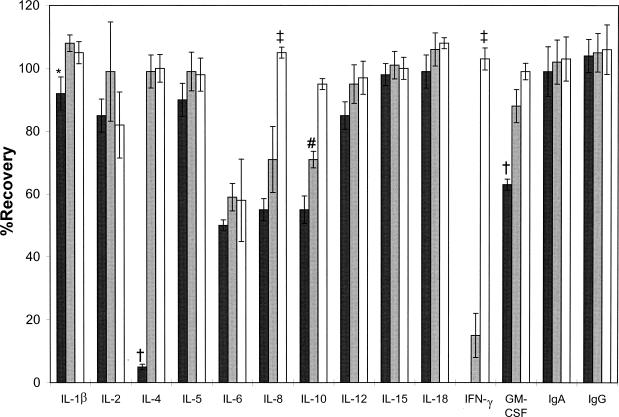

No IFN-γ, almost no IL-4 (5%), and less than 75% of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 were recovered from in vitro-loaded Weck-Cel sponges (Fig. 1); all other analytes were quantitatively (>75%) recovered. Only 15% of IFN-γ and less than 75% of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 were recovered from in vitro-loaded Ultracell sponges. Only 15% of IFN-γ and less than 75% of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 were recovered from Ultracell sponges; all other analytes were quantitatively (>75%) recovered. All analytes were quantitatively (>75%) recovered from in vitro-loaded Merocel sponges except for IL-6 (58%).

FIG. 1.

Mean percentages of recovery from different ophthalmic sponge types (black columns, Weck-Cel; gray columns, Ultracell; white columns, Merocell) loaded in vitro with known amounts of immune markers. Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated by the following symbols: *, Weck-Cel < Ultracell; †, Weck-Cel < Ultracell and Merocell; ‡, Weck-Cel and Ultracell < Merocel; #, Weck-Cel < Ultracell < Merocel.

Ninety women were randomized to six different collection groups as outlined in Materials and Methods. Table 1 compares some of the characteristics of women in each group. There were statistical differences in median age at the time of the visit (P = 0.03) and median number of years of education (P = 0.02) between groups but no differences in percentage of women who had ever used oral contraceptives, percentage of women with four or more pregnancies, median age at time of first pregnancy, and age at time of first sexual intercourse. Of the 90 paired cervical specimens collected by ophthalmic sponges, one Merocel-Ultracell (first-second sponge) and one Merocel-Weck-Cel pair was excluded because of a missing sponge weight value and a negative estimated recovery volume, respectively. Thus, 88 pairs of spears were evaluated. All specimens had IL-2 levels below the limits of detection, and most specimens had IFN-γ levels below the limits of detection; thus, these cytokines could not be evaluated for recovery from clinical specimens. The mean, median, and range of the estimated volumes of secretions for the first sponge were 46, 32, and 1 to 240 μl, respectively, and for the second sponge were 29, 18, and 1 to 240 μl, respectively. The estimated median volumes collected by Weck-Cel sponges (first sponge, 42 μl; second sponge, 25 μl) were not significantly greater than for Ultracell sponges (first sponge, 29 μl; second sponge, 17 μl) or for Merocel sponges (first sponge, 32 μl; second sponge, 16 μl) (P = 0.09, first sponge; P = 0.06, second sponge).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of women randomized to the six study groups

| Characteristic | Value for groupa

|

Pb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merocel-Ultracell | Merocel-Weck-Cel | Ultracell-Merocel | Ultracell-Weck-Cel | Weck-Cel-Ultracell | Weck-Cel Merocel | ||

| Median age (yr) | 39 | 53 | 42 | 41 | 47 | 41 | 0.03 |

| Any use of oral contraceptives (%) | 80 | 80 | 93 | 60 | 60 | 64 | 0.2 |

| Lifetime number of pregnancies ≥4 (%) | 40 | 53 | 27 | 27 | 47 | 27 | 0.5 |

| Median years of education (yr) | 6 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 0.02 |

| Median age at 1st pregnancy (yr) | 18 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 0.5 |

| Median age at 1st sexual intercourse (yr) | 17 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 0.4 |

Types of first and second sponges used are indicated (first sponge-second sponge) for each group.

Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for continuous variables, and Pearson χ2 tests were used for categorical variables. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is indicated in bold.

By nonparametric analysis of variance, there were no statistically significant differences in adjusted IL-12 and IgG concentrations extracted from the first sponge used to collect cervical secretions, but the differences for IL-10 and IgA recovery approached significance (P = 0.09) (Table 2). There were no differences in recovery levels of IL-10, IL-12, and IgG from the second sponge, but there was a significant decrease in the amount of IgA extracted from Merocel sponges (P = 0.005). However, when the data from the first and second sponges were combined, there were no significant differences in IgA concentrations (P = 0.2).

TABLE 2.

Estimated median values of IL-10, IL-12, IgG, and IgA for cervical secretions extracted from different ophthalmic spongesa

| Sponge(s) and biomarkerb | Weck-Cel | Ultracell | Merocel | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | ||||

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | 29.2 | 87.2 | 164.1 | 0.09 |

| IL-12 (pg/ml) | 278.9 | 397.5 | 298.3 | 0.7 |

| IgG (μg/ml) | 2,221.2 | 2,592.6 | 2,549.6 | 0.5 |

| IgA (μg/ml) | 325.3 | 591.6 | 590.2 | 0.09 |

| Second | ||||

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | 96.4 | 139.3 | 73.1 | 0.7 |

| IL-12 (pg/ml) | 583.6 | 616.3 | 494.7 | 0.7 |

| IgG (μg/ml) | 2,479.3 | 3,371.8 | 2,056.5 | 0.2 |

| IgA (μg/ml) | 858.5 | 995.1 | 363.3 | 0.005 |

| Combined | ||||

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | 84.7 | 105.7 | 123.9 | 0.5 |

| IL-12 (pg/ml) | 404.5 | 471.1 | 451.9 | 0.6 |

| IgG (μg/ml) | 2,382.6 | 3,054.6 | 2,254.9 | 0.4 |

| IgA (μg/ml) | 694.3 | 798.9 | 518.5 | 0.2 |

The value was estimated by correcting for the dilution resulting from the extraction from the ophthalmic sponge (see Materials and Methods).

“First” and “second” sponge refers to the sequence in which the specimen was collected in the paired collection. The numbers of first sponges are as follows: for Weck-Cel, n = 30; for Ultracell, n = 30; and for Merocel, n = 28. The numbers of second sponges are as follows: for Weck-Cel, n = 29; for Ultracell, n = 29; and for Merocel, n = 30. The number of combined sponges in each case is the sum of the numbers of first and second sponges: for Weck-Cel, n = 59; for Ultracell, n = 59; and for Merocel, n = 58.

Differences in recovery from the sponges were evaluated by the Kruskal-Wallis test, a nonparametric analysis of variance statistic, and statistical significance is highlighted in bold print.

Mixed model or adjusted means analyses were performed to control for and evaluate other covariates in addition to sponge type (Table 3). In models adjusted for sponge type, order of collection, volume of secretions, and participant, there were no significant differences in the concentrations of the immune markers recovered from each sponge type although the recovered amount of IgA was less from the Merocel sponge than from the other sponge types (P = 0.1). The smaller volumes of secretions had significantly greater concentrations of all immune markers than did the larger volumes. The first sponge had nonsignificantly greater concentrations of all immune markers than the second sponge. We observed that the variability explained by sponge type (<1% for IL-10, IL-12, and IgG, and 3% for IgA) was much less than the variability between individuals (72% for IL-10 and IL-12, 45% for IgG, and 51% for IgA).

TABLE 3.

Adjusted means of IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-12 levels from cervical secretions collected with ophthalmic spongesa

| Parameter | IgA (μg/ml) | IgG (μg/ml) | IL-10 (pg/ml) | IL-12 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sponge typeb | ||||

| Merocel | 501.6 | 2,128.5 | 88.0 | 97.5 |

| Ultracell | 726.5 | 2,647.2 | 77.0 | 84.0 |

| Weck-Cel | 627.2 | 2,746.0 | 79.2 | 87.6 |

| Volume category (μl)c | ||||

| <14.5 | 1094.8 | 4,647.5 | 125.6 | 136.0 |

| 14.5-22.8 | 937.6 | 3,725.1 | 104.9 | 115.0 |

| 22.9-43.4 | 648.2 | 2,538.2 | 87.0 | 95.1 |

| ≥43.5 | 199.7 | 810.2 | 36.0 | 39.9 |

| Collection orderd | ||||

| First sponge | 674.3 | 2,908.0 | 97.8 | 108.1 |

| Second sponge | 554.8 | 2,133.0 | 67.2 | 73.6 |

Concentrations were transformed using the Boxcox transformation (Box and Cox) to normalize the distribution of concentrations but untransformed values are presented. Values were mutually corrected for sponge type, volume of cervical secretions, collection order of the sponge, and participant. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

P values were 0.1 for IgA, 0.5 for IgG, 0.9 for IL-10, and 0.9 for IL-12.

P values were <0.0001 for IgA and IgG and 0.02 for IL-10 and IL-12.

P values were 0.2 for IgA, IL-10, and IL-12, and 0.1 for IgG.

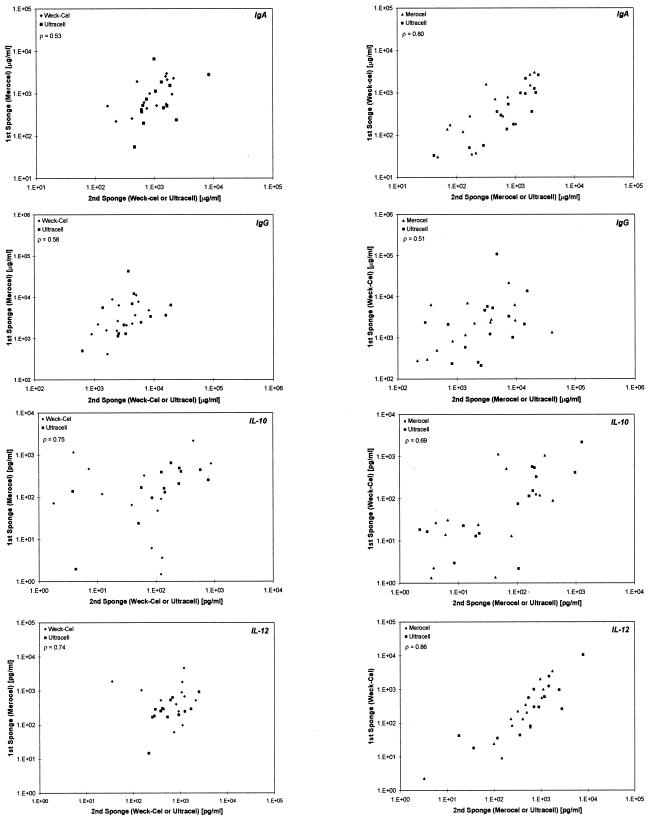

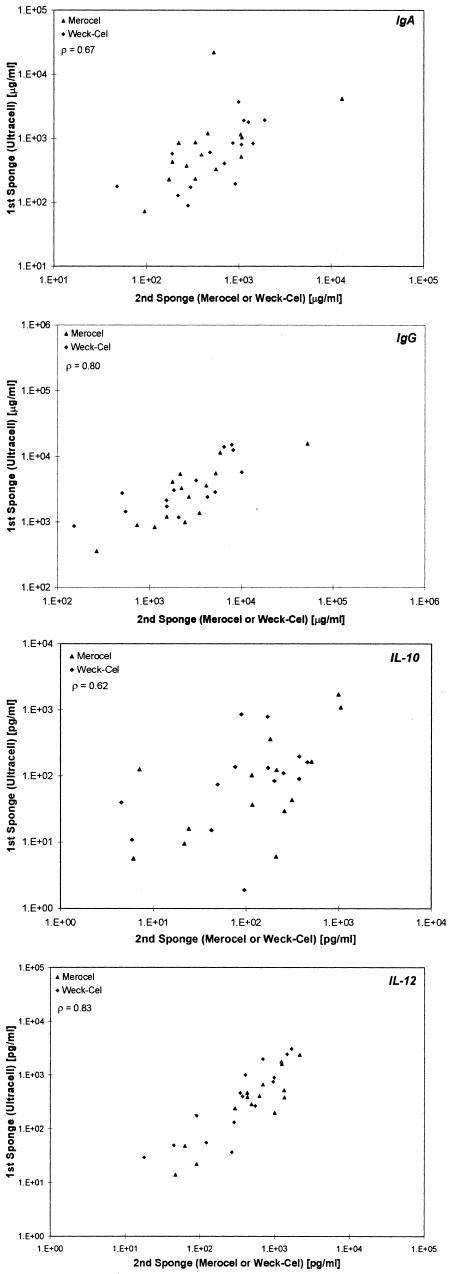

Finally, we examined the correlation of the first sponge with the combination of either of the second sponges (Fig. 2) for IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-12 from clinical specimens. For Merocel as the first sponge and Weck-Cel or Ultracell as the second sponge, the correlations for IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-12 were 0.53, 0.58, 0.75, and 0.74, respectively. For Weck-Cel as the first sponge and Merocel or Ultracell as the second sponge, the correlations for IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-12 were 0.80, 0.51, 0.69, and 0.86, respectively. For Ultracell as the first sponge and Merocel or Weck-Cel as the second sponge, the correlations for IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-12 were 0.67, 0.80, 0.62, and 0.83, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Correlations between the first sponge and second sponge (Merocel versus Ultracell or Weck-Cel, Weck-Cel versus Merocel or Ultracell, and Ultracell versus Merocel or Weck-Cel, respectively) for IgA, IgG, IL-10, and IL-10. Spearman correlations are shown for the first sponge versus both types of second sponges.

DISCUSSION

In in vitro experiments, we confirmed that IL-4 and IFN-γ may be poorly recovered from Weck-Cel ophthalmic sponges (16) and demonstrated that immune markers may be more reliably recovered from in vitro-loaded Ultracell and Merocel ophthalmic sponges. In particular, recovery from Merocel sponges, which are composed of hydroxylated polyvinyl acetate, was nearly 100% for all tested cytokines in the in vitro-loading experiment, except for IL-6, whose levels of recovery were equally poor from all sponges.

Because of the complex nature of cervical secretions compared to in vitro spiking of the collection devices, we sought to verify whether there were appreciable differences between the levels of detection of immune markers from clinical specimens. Despite the equally high recovery of IgA from each sponge type in our in vitro experiments, there was some evidence of reduced IgA recovery from clinical specimens when Merocel sponges (and Weck-Cel sponges) were used for collection. Although we randomized the women to different groups and attempted to adjust for any differences between groups (using both order and type), the groups were not perfectly balanced (e.g., as evident by the differences in age), and reduced IgA recovered from Merocel sponges could also be due to chance differences between groups. This observation is preliminary, however, and warrants confirmation. Moreover, differences in these measurements due to sponge types are relatively minor compared to the large differences between individuals, the latter being consistent with previous observations (7, 12). The large variability in genital tract immune biomarker concentrations between women is due in part to many possible determinants; for IL-10 and IL-12, they may include time of the menstrual cycle, low secretion volume, macro levels of heme contamination, high vaginal pH, numbers of lifetime sex partners, frequency of sexual intercourse, present oral contraceptive use, and smoking status (7).

In this study, there was also a nonsignificant tendency for higher IL-10 and IL-12 concentrations from Merocel sponges than from the other types. However, we note that there were no apparent systematic errors in the use of any of these sponges (Fig. 2), although there was the expected tendency of poorer correlation (greater scatter) as the measurements approached limits of detection, as best illustrated by IL-10 scatter plots. Thus, we anticipate that any of the sponges will measure relative differences in any immune marker equally well, provided that losses in immune marker recovery from the sponge do not reduce concentrations near or below the limits of detection.

One limitation of our study was that we were not able to evaluate the recovery of IFN-γ from any of the ophthalmic sponges used to collect cervical secretions due to mostly undetectable levels, and thus we were unable to confirm these differences in vivo. IL-2 was also not detectable from clinically collected specimens. IL-2 is detectable in adolescent women (5) but levels are substantially lower in older women (P. Crowley-Nowick, unpublished observations); the median age in this study was 43 years. Our study was designed primarily to detect the large differences observed for IFN-γ in vitro (post hoc analysis indicates a ≥80% power to detect a 90% reduced recovery), and thus subtle differences in recovery would not be detectable.

A second limitation is that the small volumes of cervical secretions recovered (∼50 μl) and the low concentrations of some immune markers after extraction restricted the number of immune markers that could be measured by ELISA in this validation study. Specifically, we did not examine IL-4, which appeared to be problematic for Weck-Cel sponges as determined from our in vitro measurements. We are now exploring other assay systems that permit multiple measurements from the same aliquot of cervical secretions and thereby circumvent this limitation (3).

We conclude that there may be some advantages to using Merocel ophthalmic sponges instead of Weck-Cel or Ultracell sponges. However, further studies are needed. The unexplained tendency of poorer IgA recovery from clinical specimens collected with Merocel sponges warrants caution, and it may be necessary to select sponges based on specific study objectives. For example, if the lower IgA recovery from Merocel sponges is confirmed, it may be less appropriate to use this sponge to monitor anti-HPV IgA responses to vaccination. We again note that potential differences between sponges are small compared to the differences between women, which are likely due to a number of factors (e.g., time of the menstrual cycle) that contribute to differences in genital tract physiology. Finally, optimizing specimen collection for measurements of genital tract immune responses may be important to human studies such as vaccine trials for protection against sexually transmitted infections.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a series of National Cancer Institute contracts.

We gratefully acknowledge the IMS group (Rockville, Md.) of Julie Buckland and John Schussler. We offer special recognition for the excellent work of the study staff in Costa Rica. We also acknowledge the collaboration of health authorities in Costa Rica for their enthusiastic support of this project and of the outreach workers of the Ministry of Health of Costa Rica, who carried out the population census, for their dedication to the health of the people of Guanacaste. Finally, we thank Lisa M. McShane (Biometric Research Branch, NCI, NIH, DHHS) for her statistical expertise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Box, G. E. P., and D. R. Cox, 1964. An analysis of transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B 26:211-243. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bratti, M. C., A. C. Rodríguez, M. Schiffman, A. Hildesheim, J. Morales, M. Alfaro, D. Guillén, M. Hutchinson, M. E. Sherman, C. Eklund, J. Schussler, J. Buckland, L. A. Morera, F. Cárdenas, M. Barrantes, E. J. Pérez, T. Cox, R. D. Burk, and R. Herrero. Description of a seven-year prospective study of HPV infection and cervical neoplasia among 10,000 women in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. Rev. Panam. Salud. Publica, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Castle, P. E., T. M. Phillips, A. Hildesheim, R. Herrero, M. C. Bratti, A. C. Rodriguez, L. A. Morera, R. Pfeiffer, M. L. Hutchinson, L. A. Pinto, and M. Schiffman. Immune profiling of plasma and cervical secretions. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev., in press. [PubMed]

- 4.Castle, P. E., A. Hildesheim, F. P. Bowman, H. D. Strickler, J. L. Walker, T. Pustilnik, R. P. Edwards, and P. A. Crowley-Nowick. 2002. Cervical concentrations of interleukin-10 and interleukin-12 do not correlate with plasma levels. J. Clin. Immunol. 22:23-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowley-Nowick, P. A., J. H. Ellenberg, S. H. Vermund, S. D. Douglas, C. A. Holland, and A. B. Moscicki. 2000. Cytokine profile in genital tract secretions from female adolescents: impact of human immunodeficiency virus, human papillomavirus, and other sexually transmitted pathogens. J. Infect. Dis. 181:939-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fichorova, R. N., and D. J. Anderson. 1999. Differential expression of immunobiological mediators by immortalized human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells. Biol. Reprod. 60:508-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gravitt, P. E., A. Hildesheim, R. Herrero, M. Schiffman, M. E. Sherman, M. C. Bratti, A. C. Rodriguez, L. A. Morera, F. Cardenas, F. P. Bowman, K. V. Shah, and P. A. Crowley-Nowick. 2003. Correlates of IL-10 and IL-12 concentrations in cervical secretions. J. Clin. Immunol. 23:175-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harro, C. D., Y. Y. Pang, R. B. Roden, A. Hildesheim, Z. Wang, M. J. Reynolds, T. C. Mast, R. Robinson, B. R. Murphy, R. A. Karron, J. Dillner, J. T. Schiller, and D. R. Lowy. 2001. Safety and immunogenicity trial in adult volunteers of a human papillomavirus 16 L1 virus-like particle vaccine. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93:284-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrero, R., M. H. Schiffman, C. Bratti, A. Hildesheim, I. Balmaceda, M. E. Sherman, M. Greenberg, F. Cardenas, V. Gomez, K. Helgesen, J. Morales, M. Hutchinson, L. Mango, M. Alfaro, N. W. Potischman, S. Wacholder, C. Swanson, and L. A. Brinton. 1997. Design and methods of a population-based natural history study of cervical neoplasia in a rural province of Costa Rica: the Guanacaste Project. Rev. Panam. Salud. Publica 1:362-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrero, R., A. Hildesheim, C. Bratti, M. E. Sherman, M. Hutchinson, J. Morales, I. Balmaceda, M. D. Greenberg, M. Alfaro, R. D. Burk, S. Wacholder, M. Plummer, and M. Schiffman. 2000. Population-based study of human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in rural Costa Rica. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92:464-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hildesheim, A., M. C. Bratti, R. P. Edwards, M. Schiffman, A. C. Rodriguez, R. Herrero, M. Alfaro, L. A. Morera, S. V. Ermatinger, B. T. Miller, and P. A. Crowley-Nowick. 1998. Collection of cervical secretions does not adversely affect Pap smears taken immediately afterward. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:491-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hildesheim, A., L. M. McShane, M. Schiffman, M. C. Bratti, A. C. Rodriguez, R. Herrero, L. A. Morera, F. Cardenas, L. Saxon, F. P. Bowman, and P. A. Crowley-Nowick. 1999. Cytokine and immunoglobulin concentrations in cervical secretions: reproducibility of the Weck-Cel collection instrument and correlates of immune measures. J. Immunol. Methods 225:131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hildesheim, A., R. L. Ryan, E. Rinehart, S. Nayak, D. Wallace, P. E. Castle, S. Niwa, and W. Kopp. 2002. Simultaneous measurement of several cytokines using small volumes of biospecimens. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 11:1477-1484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson, E. L., A. Rudin, L. Wassen, and J. Holmgren. 1999. Distribution of lymphocytes and adhesion molecules in human cervix and vagina. Immunology 96:272-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nardelli-Haefliger, D., D. Wirthner, J. T. Schiller, D. R. Lowy, A. Hildesheim, F. Ponci, and P. De Grandi. 2003. Specific antibody levels at the cervix during the menstrual cycle of women vaccinated with human papillomavirus 16 virus-like particles. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 95:1128-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohan, L. C., R. P. Edwards, L. A. Kelly, K. A. Colenello, F. P. Bowman, and P. A. Crowley-Nowick. 2000. Optimization of the Weck-Cel collection method for quantitation of cytokines in mucosal secretions. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7:45-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SAS Institute. 1992. I. The mixed procedure. SAS technical report P-229: SAS/STAT software changes and enhancements. SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.

- 18.Searle, S. R., G. Casella, and C. E. Meculloh. 1992. Variance components. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 19.Snowhite, I. V., W. E. Jones, J. Dumestre, K. Dunlap, P. S. Braly, and M. E. Hagensee. 2002. Comparative analysis of methods for collection and measurement of cytokines and immunoglobulins in cervical and vaginal secretions of HIV and HPV infected women. J. Immunol. Methods 263:85-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]