Abstract

Malakoplakia is a rare granulomatous disease that occurs commonly in the urinary tract and secondarily in the gastrointestinal tract. Most reported cases of malakoplakia are associated with immunosuppressive diseases or chronic prolonged illness. Here, we report a rare case of malakoplakia in a young healthy adolescent without any underlying disease. A 19-year-old female was referred to our hospital following the discovery of multiple rectal polyps with sigmoidoscopy. She had no specific past medical history but complained of recurrent abdominal pain and diarrhea for 3 months. A colonoscopy revealed diverse mucosal lesions including plaques, polyps, nodules, and mass-like lesions. Histological examination revealed a sheet of histiocytes with pathognomonic Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. We treated the patient with ciprofloxacin, the cholinergic agonist bethanechol, and a multivitamin for 6 months. A follow-up colonoscopy revealed that her condition was resolved with this course of treatment.

Keywords: Malakoplakia, Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, Diverse mucosal lesions

INTRODUCTION

Malakoplakia is a rare, chronic, granulomatous inflammatory disease that was first described by Michaelis and Gutmann in 1902. The name "malakoplakia" was derived from the Greek "malakos" (soft) and "plakos" (plaque) in 1903 by Von Hansemann. Malakoplakia is most commonly found in the urinary tract, but has been reported in the gastrointestinal tract, lung, brain, lymph node, adrenal, tonsil, conjunctiva, skin, bone, abdominal wall, pancreas, retroperitoneum, and female genital tract [1]. Malakoplakia is associated with many coexisitng conditions, such as organ transplantation, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, allergic conditions, cytotoxic chemotherapy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, malignancies, steroid use, alcohol abuse, poorly controlled diabetes, ulcerative colitis, and malnutrition [1]. It is very rare in young people without underlying disease. Here, we report a case of malakoplakia in an otherwise healthy 19-year-old female with a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 19-year-old female was referred to our hospital following the discovery of multiple polyps in the rectum with sigmoidoscopy. Her clinical symptoms were recurrent low abdominal pain and loose stool with blood and foul odor 4 to 5 times a day for 3 months. She complained of a squeezing type abdominal pain relieved after defecation. When the patient was admitted, she was in relatively good condition with no specific past medical history and did not complain of fever, chill, anorexia, weight loss, or cold sweating.

On physical examination, there were no definite abnormal findings except for mild epigastric tenderness and slightly increased bowel sounds. Blood pressure was 110/76 mmHg, pulse rate 106 beats per minute, body temperature 36.3℃. Laboratory tests revealed hemoglobin at 9.0 g/dL, white blood cell (WBC) count at 9,050/µL with 26.6% neutrophils, 27.2% lymphocytes, 15.2% monocytes, and 0.8% eosinophils. A peripheral blood smear showed normocytic normochromic anemia, Fe of 18 µg/dL, total iron binding capacity of 286 µg/dL, 0.8% reticulocytes, and stool occult blood over 1,000 ng/mL. Inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were mildly elevated to 3.03 mg/dL and 42 mm/hr, respectively. Urine analysis with microscopic exam showed no abnormality. Stool acid-fast bacillus and tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction were negative, and gram stain showed WBC 10 to 25 and a number of gram-positive cocci and gram-negative bacilli. In the stool culture, Salmonella or Shigella was not isolated and blood cultures were negative. Rheumatic factor was normal, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody was negative. Serum IgG, IgE, and hemolytic complement 50 (CH50) complement levels were slightly elevated to 1,800 mg/dL, 236 IU, and 54.2 U/mL, respectively. IgA, IgM, complement 3, and complement 4 were within normal range.

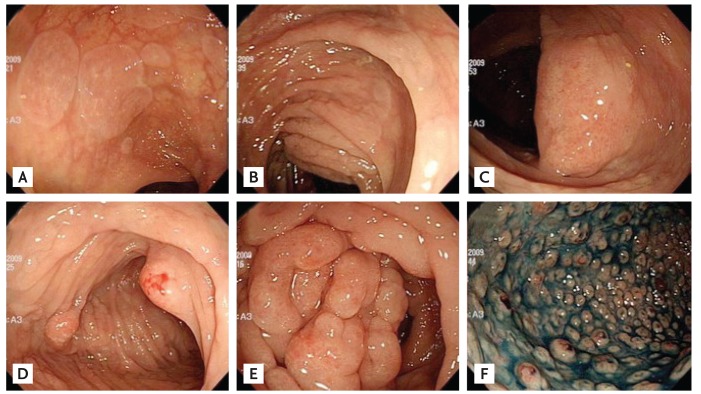

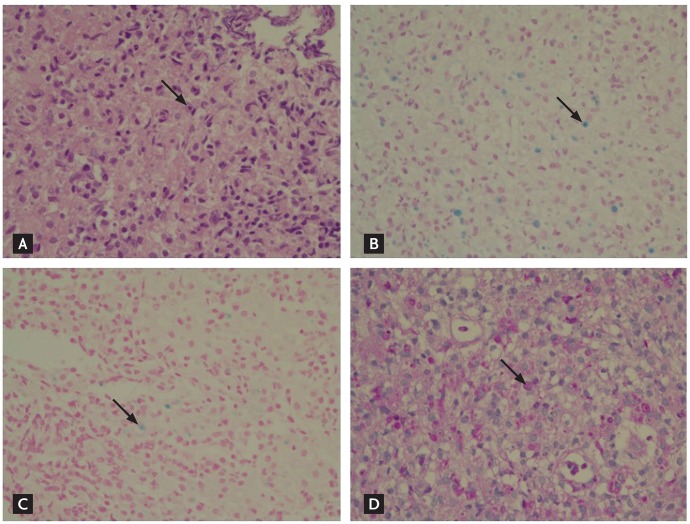

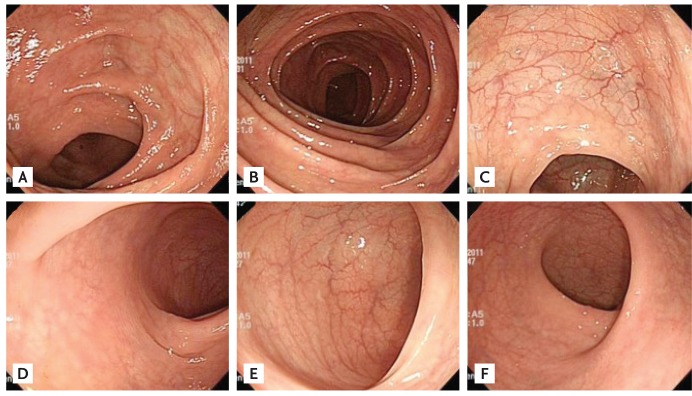

Colonoscopy revealed very diverse circular or flat elevated mucosal lesions up to 10 cm in size from the cecum to the descending colon, small nodules, mass-like lesions, and erosive small polypoid lesions throughout the colon, particularly in the sigmoid colon (Fig. 1). Biopsies were taken in eight different places. After colonoscopy, we initially suspected atypical lymphoma or malignancy. However, lactate dehydrogenase and tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 125, CA 19-9, and α-fetoprotein were within normal range and an abdominopelvic computed tomography scan revealed no other abnormal findings, except for localized multiple small reactive lymph node enlargements along the mesentery. Histological examination of colon lesion biopsies revealed dense histiocyte infiltration with round inclusions of varying sizes in the cytoplasm. Many of these inclusions had round laminated structures with a central dark area and peripheral pale halo. These structures were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), Alcian blue, Prussian blue, and Gomori methenamine silver stains to confirm the presence of Michaelis-Gutmann bodies with pathognomonic features of malakoplakia (Fig. 2). These diagnostic tests confirmed the diagnosis of malakoplakia. During antibiotic treatment, diarrhea and abdominal pain improved so she was discharged with instructions to take 500 mg ciprofloxacin twice a day, 25 mg bethanecol three times a day, and 60 mg ascorbic acid once a day by mouth. After the treatment started, the symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhea disappeared in a week. After 2 months, CRP, ESR, and hemoglobin were nearly normal with values of 0.32 mg/dL, 2 mm/hr, and 12.5 g/dL, respectively. The patient remained on this regimen for 6 months. During the treatment period, no drug side effects were observed. Previous abnormal colonoscopy findings were remarkably improved after 6 months of follow-up, and returned to normal after the end of 12 months (Fig. 3). Outpatient follow-up visits have confirmed that she is currently healthy.

Figure 1.

Initial colonoscopy findings. (A) Proximal colon mucosa shows circular, flat elevated lesions and (B) a very long flat elevated lesion. (C) A mass lesion is seen with (D) a large polypoid lesion resembling Cap polyposis, and (E) a large multigranular mass-like lesion throughout the whole colon. (F) The sigmoid colon and rectum mucosa shows multiple small polypoid lesions resembling familial adenomatous polyposis.

Figure 2.

Histological findings. Specific histological stains show concentrically layered basophilic inclusions and Michaelis-Gutmann bodies with pathognomonic features of malakoplakia (arrows) (A, H&E stain, × 400; B, Alcian blue, × 400; C, Prussian blue, × 400; D, periodic acid-Schiff, × 400).

Figure 3.

Follow-up colonoscopy findings 12 months after the end of treatment showing normal mucosa throughout (A, B, C, D, and E) the colon and (F) sigmoid colon.

DISCUSSION

The gastrointestinal tract is the second most common site of involvement by malakoplakia, and most of these cases involve the rectum and colon. Clinical manifestation of colonic malakoplakia is very diverse, from asymptomatic to diarrhea, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, intestinal obstruction, vomiting, malaise, fever, and constipation [1]. However, clinically characteristic symptoms or signs diagnosing malakoplakia do not exist. Colonic malakoplakia may involve segmentally or diffusely. Endoscopically, malakoplakia commonly presents in the early stages as soft yellow to tan mucosal plaques or in the late stages as raised, grey to tan lesions in various sizes with peripheral hyperemia and a central depressed area [2]. Malakoplakia can be diagnosed by histology with the presence of the mineralized basophilic structures and Michaelis-Gutmann bodies [3].

The etiology and pathogenesis of malakoplakia is still not fully understood, but multiple possible mechanisms have been suggested. The involvement of microorganisms is supported by reports of patients with malakoplakia who have chronic infections with various organisms such as Escherichia coli, Proteus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Staphylococcus aureus. Infections induced by the microorganisms mentioned above are much more common than malakoplakia; therefore, other factors must contribute. Malakoplakia may also be caused by a defect in lysosomal processing of microorganisms undergoing phagocytosis by macrophages or monocytes. Therefore, incompletely digested microorganisms accumulate in lysosomes and lead to mineralization of calcium and iron salts on residual microorganism glycolipids. These Michaelis-Gutmann bodies can be intracellular or extracellular when stained with PAS, Prussian blue for iron, and von Kossa for calcium. Microtubules are essential to bacterial phagocytosis and lysosomal fusion. The assembly of microtubules is stimulated by cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and inhibited by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). β-Glucuronidase located in the lysosome is essential to efficient lysosomal bactericidal activity. Both low cGMP level and reduced β-glucuronidase activity have been reported in patients with malakoplakia [4,5].

In this patient, we initially suspected atypical lymphoma, familial adenomatous polyposis, or other uncommon cancers because of a wide variety of mucosal lesions throughout the colon. We performed multiple random colonic biopsies to verify the diagnosis and, in all biopsies, Michaelis-Gutmann bodies characteristic of malakoplakia were observed. ESR and CRP were mildly elevated, but blood and stool cultures were negative. No definite infectious signs were checked, as the patient did not have any specific infectious disease such as pneumonia or otitis media in her childhood. We could not measure polymorphonuclear leukocyte function through stimulation by cGMP and inhibition by cAMP. There may also be a corrlation between immunosuppression or chronic prolonged iellness and malakoplakia because immunodeficient individuals and patients receiving chemotherapy or immmunosuppressive therapy for transplantation constitute a considerable portion of malakoplakia cases [6]. Furthermore, malakoplakia seems to be correlated with malignant neoplasms and systemic diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosis, mycotic infections, liver diseases, sarcoidosis, ulcerative colitis, cachexia, and drug addiction [1]. Some authors hypothesized that the coincidence of malakoplakia with colonic and rectal adenocarcinoma might begin with local alteration of gut flora and advised physicians to carefully search for a colorectal neoplasm when malakoplakia appears histologically [7]. However, the patient in this study was not immunocompromised and did not have any suspicious findings of autoimmune disease. Generally, malakoplakia should be differentiated from Crohn's disease, military tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Whipple disease, Chediak-Higashi syndrome, and malignancies such as colon cancer and lymphoma.

To rule out a particularly serious malignant disease and evaluate the response to treatment, follow-up colonoscopies with random biopsies were performed four times at 3, 6, and 12 months, and at 6 months after the end of treatment for a total follow-up period of 18 months. No other malignancies were found and mucosal lesions improved gradually upon sequential endoscopic examinations.

Medical treatment of malakoplakia is based on the eradication of microorganisms. The first strategy is to increase the intracellular cGMP to cAMP ratio using cholinergic agonists such as bethanechol and ascorbic acid to improve lysosomal function. The second therapeutic strategy is to treat the presumed microorganism infection within the colon by antibiotics. The antibiotics trimethoprim/sulphamethoxazol, rifampicin, and particularly ciprofloxacin have all been used in the treatment of malakoplakia, because these are able to enter macrophages and contribute to intracellular microorganism death [1]. The duration of treatment is not fixed, but long-term treatment is advised, although its efficacy still remains debated. According to the report, 6 months to 3 years, there was one case of antibiotic treatment. An underlying condition is the most crucial factor affecting malakoplakia mortality, and significant morbidity is related to the chronic underlying condition, which can resist local and systemic therapy.

In this case, the patient's symptoms improved very quickly after antibiotic treatment. Since her symptoms and clinical results improved without aggravation after medical treatment, we speculated that she suffered from malakoplakia without coexisting disease and that immune maturation with aging might play a role.

The etiology of colonic malakoplakia in this patient was unclear since there were no microorganisms in the stool and blood culture. The patient had no specific past medical history and was not immunodeficient, did not have a malignancy or any chronic illness, and was not in the most frequently affected age group.

In Korea, three cases of malakoplakia have been reported [8-10]. One case involved the ascending colon and the others involved the rectum. One of these cases was treated surgically [8], another treated by endoscopic polypectomy [9], and the last one treated medically [10]. This is the first case of malakoplakia with very diverse mucosal lesions throughout the entire colon in a healthy young female with no associated disease. Our case illustrates that when very diverse and atypical mucosal lesions are detected on colonoscopy, physicians should consider malakoplakia.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.

References

- 1.Yousef GM, Naghibi B, Hamodat MM. Malakoplakia outside the urinary tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:297–300. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-297-MOTUT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinrach DM, Wang KL, Cisler JJ, Diaz LK. Pathologic quiz case: a 54-year-old liver transplant recipient with diffuse thickening of the sigmoid colon: malakoplakia of the colon associated with liver transplant. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:e133–e134. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-e133-PQCAYL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renshaw A, Murphy W. Lower urinary tract. In: Cortran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, Robbins SL, editors. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1999. p. 1002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewin KJ, Fair WR, Steigbigel RT, Winberg CD, Droller MJ. Clinical and laboratory studies into the pathogenesis of malacoplakia. J Clin Pathol. 1976;29:354–363. doi: 10.1136/jcp.29.4.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdou NI, NaPombejara C, Sagawa A, et al. Malakoplakia: evidence for monocyte lysosomal abnormality correctable by cholinergic agonist in vitro and in vivo. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1413–1419. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712292972601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biggar WD, Crawford L, Cardella C, Bear RA, Gladman D, Reynolds WJ. Malakoplakia and immunosuppressive therapy: reversal of clinical and leukocyte abnormalities after withdrawal of prednisone and azathioprine. Am J Pathol. 1985;119:5–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates AW, Dev S, Baithun SI. Malakoplakia and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:171–173. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.73.857.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn BG, Sun BH, Kim HS. A case report of malakoplakia occurred in the ascending colon. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 1996;12:149–153. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh KC, Rhee PL, Kim JJ, et al. Malakoplakia. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;16:254–259. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee DH, Cheong JY, Park WI, et al. A case of malakoplakia treated by antibiotics in the rectum. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;30:99–102. [Google Scholar]