Abstract

We produced a recombinant cysteine proteinase of Clonorchis sinensis and tested its value as an antigen for serologic diagnosis of C. sinensis infections. The predicted amino acid sequence of the cysteine proteinase of C. sinensis was 58, 48, and 40% identical to those of cathepsin L cysteine proteinases from Paragonimus westermani, Schistosoma japonicum, and Fasciola hepatica, respectively. Western blotting analysis showed that sera from patients infected with C. sinensis strongly reacted with the recombinant protein and that sera from patients infected with S. japonicum weakly reacted with the recombinant protein. Antibody against the recombinant protein stained proteins migrating at about 37 and 28 kDa in C. sinensis adult worm crude extracts. Immunostaining revealed that the cysteine proteinase of C. sinensis was located in the intestinal epithelial cells of the adult parasite and in intrauterine eggs. The specificity and sensitivity of the recombinant antigen or C. sinensis adult worm crude extracts were assessed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using serum samples from humans infected with different parasites, including 50 patients with clonorchiasis, and negative controls. The sensitivities of the ELISA with the recombinant antigen and C. sinensis adult worm crude extracts were 96 and 88%, respectively. The specificities of the ELISA with the recombinant antigen and C. sinensis adult worm crude extracts were 96.2 and 100%, respectively. The results suggested that the recombinant cysteine proteinase-based ELISA could provide a highly sensitive and specific assay for diagnosis of clonorchiasis.

Clonorchiasis, which is caused by Clonorchis sinensis, is an important food-borne parasitic disease of humans in Eastern Asian countries, including China, Korea, and Vietnam. Reportedly, about 7 million people are infected in these areas by eating raw or undercooked freshwater fish (6). Definitive diagnosis is achieved by finding the eggs in feces, but more cooperative diagnostic methods are necessary for epidemiological surveys because of the difficulties of collecting stool samples from individuals. Additionally, the method is not adequate for early diagnosis, because the flukes start releasing eggs in feces after 4 weeks of infection (16). With the advance of immunological diagnostic methods, the detection of specific antibody has been used as one of the routine diagnostic tests for clonorchiasis, especially for epidemiological surveys.

In conventional serological diagnosis of clonorchiasis, the adult worm crude antigens of C. sinensis are used. However, the crude antigens reduce the specificity of the serological test due to cross-reactivity with parasites sharing similar antigens (8). Cathepsin L, one of the cysteine proteinases, has been found in many species of parasites (7, 15, 21, 22). Cathepsin L is secreted by all stages of the developing parasites and is highly antigenic in infected animals. Reportedly, the purified or recombinant cysteine proteinase antigens have been used for diagnosis of human paragonimiasis (9), fascioliasis (1, 4, 5), and schistosomiasis (2, 11).

In this study, we cloned and expressed a C. sinensis cysteine proteinase and first evaluated the specificity and sensitivity of the recombinant protein in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) by comparing it with adult worm crude antigen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. sinensis adult worms and crude extracts.

C. sinensis metacercariae were obtained from naturally infected fish in the city of Shunde in China. Rabbits were infected with 400 metacercariae, and adult worms were collected from bile ducts of the infected rabbits at 12 days postinfection. Adult worms were freeze-dried and crushed to powder. Cold acetone was added to the worm powder, and then the sample was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The precipitate was incubated in physiological saline for 6 days at 4°C and centrifuged to remove the pellets.

Sera.

A total of 76 human serum samples of parasitologically and clinically proven cases were used. Serum samples referred to herein as clonorchiasis sera (n = 50) or schistosomiasis sera (n = 5) were collected from the patients infected with C. sinensis or Schistosoma japonicum, respectively, in the areas where these parasites are endemic in China. The sera from patients infected with other parasites, including Paragonimus westermani (n = 2), Fasciola hepatica (n = 3), Taenia solium (n = 2), Gnathostoma spinigerum (n = 3), Dirofilara immitis (n = 3), Diphyllobothrium latum (n = 3), Trichuris trichiura (n = 2), Anisakis simplex (n = 2), and Entamoeba histolytica (n = 1), were collected from patients in Japan. Serum samples from 48 healthy Japanese subjects without parasitological infections were used as negative controls.

Preparation of C. sinensis cDNA.

Total RNA was isolated from adult worms using TRIZOL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions and treated with DNase (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Reverse transcription was performed using Ready-To-Go You-Prime First-Strand beads (Amersham Biosciences Co., Piscataway, N.J.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 3 μg of the total RNA and 1 μg of oligo12−18 (dT) (0.5 μg/μl; Amersham Biosciences Co.) were added to the Ready-To-Go tube, and this was followed by the addition of RNase-free water to produce a final volume of 33 μl. The tube was incubated at 37°C for 60 min and then at 90°C for 5 min.

Sequencing of cysteine proteinase of C. sinensis.

The gene encoding full-length cysteine proteinase of C. sinensis was amplified by PCR from C. sinensis cDNA using oligonucleotide primers with BamHI and EcoRI restriction enzyme sites added (underlined). The primers were designed from the reported nucleotide sequences of C. sinensis cysteine proteinase (GenBank accession number AF093242) as follows: 5′-CGG GAT CCC GAT GCG ACT TTT CGT GTG TTG-3′ and 5′-CGG AAT TCC GCT ATT TGA TAA TCG CTG TAG TA-3′. The PCR mixture (total volume of 100 μl) consisted of 10 μl of 100 ng of C. sinensis cDNA, 10 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 4 μl of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (2.5 mM), 1.5 U of Taq polymerase (Takara Shuzo Co., Kyoto, Japan), and 10 μl of 10 μM concentrations of each primer. DNA was amplified for 35 cycles (each cycle consisted of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 52°C, and 60 s of extension at 72°C). The purified PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.), and the resulting fragments were cloned into pGEM-3Zf (+) vector (Promega). The nucleotide sequences were determined using Dye Primer Cycle Sequencing kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and an ABI DNA automatic sequencer (model 373S). The DNA sequences were assembled and analyzed using the DNASIS software (Hitachi Software Engineering, Tokyo, Japan). The BLAST network service was used to search the DNA and protein database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Expression and purification of recombinant protein.

The gene encoding pro-cysteine proteinase of C. sinensis was amplified by PCR from C. sinensis cDNA using oligonucleotide primers with BamHI and EcoRI restriction enzyme sites added (underlined). The primers were designed from the nucleotide sequences which were determined in “Sequencing of cysteine proteinase of C. sinensis” as follows: 5′-CGG GAT CCC GGC TTT GGC CAG AAC TAC T-3′ and 5′-CGG AAT TCC GCT ATT TGA TAA TCG CTG TAG TA-3′. The conditions for PCR were the same as those in “Sequencing of cysteine proteinase of C. sinensis.” The purified PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and were cloned into the pTrcHis expression vector (Invitrogen). The recombinant plasmid was transformed into an Escherichia coli DH5α strain, and the expression of polyhistidine-containing recombinant proteins was induced by adding isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranaside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 1 mM at 37°C for 3 h. The induced cells were harvested and disrupted by sonication in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The recombinant protein expressed as inclusion bodies was solubilized completely with 6 M urea in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) and then subjected to a His Trap kit (Amersham Biosciences Co.) for affinity purification of histidine-tagged proteins according to the manufacturer's instructions. Urea was removed from the sample protein solution by stepwise dilution of urea with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) in a His Trap chelating column according to the method of Colangeli et al. (3). The recombinant protein was eluted with 500 mM imidazole, and then the imidazole was removed from samples with a PD-10 column (Amersham Biosciences Co.) and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (11% gel) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to assess their purity.

Preparation of antiserum.

Antiserum against the recombinant protein was collected from BALB/c mice that received intradermal injections with approximately 100 μg of recombinant protein mixed with complete Freund's adjuvant followed by four booster injections of 50 μg of protein mixed with incomplete Freund's adjuvant at 2-week intervals.

Western blotting analysis.

Test samples included crude extracts from adult worms and the recombinant protein. Aliquots of crude extracts (20 μg) or recombinant protein (0.4 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE (11% gel), electrotransferred to nitrocellulose sheets, and immunostained with sera from patients infected with C. sinensis, sera from patients infected with S. japonicum, sera from healthy adults, or sera from mice immunized against recombinant protein (1:100 dilution). Goat anti-human or mouse immunoglobulin G (Fab specific) alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was used as the second antibody, and the alkaline phosphatase was developed in 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-p-toluidine salt and nitroblue tetrazolium.

Immunocytolocalization.

C. sinensis adult worms were processed for light microscopic observation according to the established method (10% formalin fixation and hematoxylin and eosin staining). For immunohistochemical staining, formalin-fixed sections 4 μm thick were incubated with the sera from mice immunized against recombinant protein or normal mouse serum (1:100 dilution) for 1 h, washed, and further processed using the HistoStain SP kit (ZYMED Laboratories, South San Francisco, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

ELISA.

The antigens were assayed at several concentrations to determine the sensitivity of the ELISA, and the optimal concentration of the antigens was determined to be 5 μg/ml (data not shown). ELISA was performed as reported by Matsuda et al. (12) with slight modifications. Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates (MaxiSorp; Nalge Nunc International, Tokyo, Japan) were sensitized with either recombinant protein or adult worm extracts at a concentration of 5 μg/ml in 0.05 M bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6 (100 μl/well), for 3 h at 37°C and overnight at 4°C. After the microplates were washed three times with 0.15 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-0.05% Tween 20, they were blocked with 150 μl of PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at 37°C. After washing as described above, the microplates were probed with a 1:200-diluted human serum sample (100 μl/well), in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at 37°C. After washing, 100 μl of 1:10,000-diluted goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (Fab specific) peroxidase conjugate (Sigma Chemical Co.) was incubated for 45 min at 37°C. For color development, 2-2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added to each well as substrate (0.3 mg/ml; 100 μl/well), and the reaction was terminated after 60 min by adding 50 μl of 1.25% sodium fluoride per well. Absorbance at 414 nm was monitored with a Multiskan JX plate reader (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). All samples were carried out in duplicate. The cutoff point was set at three times the mean values of the A414 for the negative samples from 48 healthy persons.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Nucleotide sequence data reported in this article are available in the GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ databases under accession number AY273802.

RESULTS

Molecular characterization of cysteine proteinases of C. sinensis.

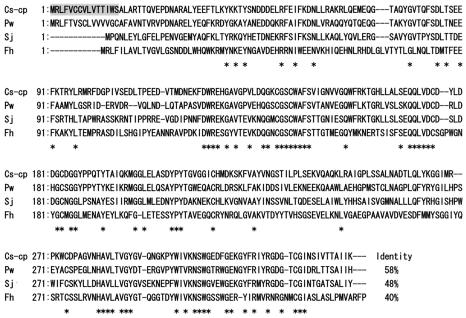

The gene encoding the cysteine proteinase was successfully amplified by PCR from cDNA of C. sinensis collected from China using the primers designed from the reported nucleotide sequences of C. sinensis cysteine proteinase. The amplicon from the cysteine proteinase, designated Cs-cp, was sequenced, and its amino acid sequence was deduced. The Cs-cp clone was 981 bp, which encoded a protein of 326 amino acid residues, with a molecular mass of 36,541 Da (Fig. 1). Weight matrix calculations based on the algorithm determined by von Heijne (19) allows predictions of the most likely cleavage site for the N-terminal signal sequence. In the case of Cs-cp, possible signal sequence cleavage sites of Cs-cp were predicted after Ser 15 (Fig. 1), which after cleavage results in a proprotein of 311 residues with a predicted molecular mass of 34,788 Da. The amino acid sequence of Cs-cp had a similarity of 99% to that of the reported sequence of C. sinensis cysteine proteinase (GenBank accession number AAF40479). The Cs-cp protein was 58% identical to the cathepsin L from P. westermani (GenBank accession number AAB93494), 48% identical to the cathepsin L from S. japonicum (GenBank accession number AAM44058), and 40% identical to the cathepsin L from F. hepatica (GenBank accession number BAA23743) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of C. sinensis cysteine proteinase (Cs-cp) open reading frame, with that of P. westermani cathepsin L (Pw) (GenBank accession number AAB93494), S. japonicum cathepsin L (Sj) (GenBank accession number AAM44058), and F. hepatica cathepsin L (Fh) (GenBank accession number BAA23743). The putative signal peptide of Cs-cp is shaded. Amino acid residues conserved in all four sequences are indicated by asterisks. The identities with Cs-cp are represented along the margins. Gaps are represented by dashed lines. Amino acid positions are shown to the left of the sequences.

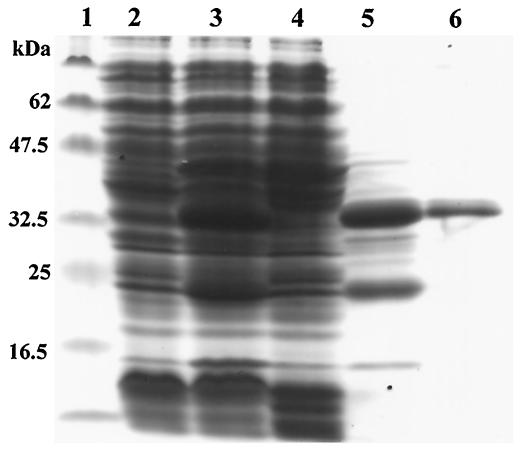

Expression of Cs-cp recombinant protein.

The Cs-cp recombinant protein was much more highly expressed in inclusion bodies (Fig. 2, lane 5) than in the supernatant of the induced cells (Fig. 2, lane 4). Protein synthesis was induced more efficiently in the sample with 1 mM IPTG treatment (Fig. 2, lane 3) than in the sample without treatment (Fig. 2, lane 2). The recombinant protein could be purified at the single-band level using a His Trap kit and eluted with 500 mM imidazole (Fig. 2, lane 6).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE (11% gel) analysis of the Cs-cp recombinant protein. Lane 1, molecular mass standards (masses shown on the left side); lane 2, lysate of E. coli with Cs-cp before induction; lane 3, lysate of E. coli with Cs-cp after induction; lane 4, supernatants of lysate of E. coli with Cs-cp after induction; lane 5, precipitants of lysate of E. coli with Cs-cp after induction; lane 6, Cs-cp recombinant proteins purified by the affinity purification method.

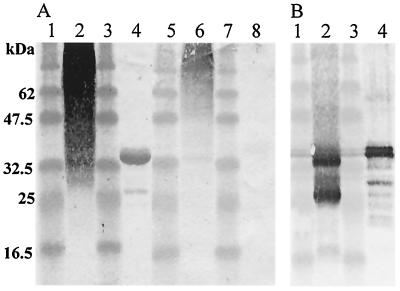

Western blotting analysis of Cs-cp recombinant protein.

The pooled sera from patients infected with C. sinensis positively immunostained adult worm crude extracts and the Cs-cp recombinant protein (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 4), and the pooled sera from patients infected with S. japonicum weakly stained adult worm extracts and the Cs-cp recombinant protein (Fig. 3A, lanes 6 and 8).

FIG. 3.

(A) Western blotting analysis of C. sinensis adult worm crude extracts (lanes 2 and 6) and Cs-cp recombinant protein (lanes 4 and 8) stained with the pooled sera from patients infected with C. sinensis (lanes 2 and 4) and with the pooled sera from patients infected with S. japonicum (lanes 6 and 8). Lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7, molecular mass standards (masses shown on the left side). (B) Western blotting analysis of reactivity of sera from mice immunized against the Cs-cp recombinant protein with C. sinensis adult worm crude extracts (lane 2) and Cs-cp recombinant protein (lane 4). Lanes 1 and 3, molecular mass standards (masses shown on the left side).

The sera from mice immunized against the Cs-cp recombinant protein stained 2 bands migrating at about 37 and 28 kDa in adult worm extracts (Fig. 3B, lane 2) and stained the Cs-cp recombinant protein (Fig. 3B, lane 4). The positive staining of the 37-kDa protein was expected because this is the predicted size of the Cs-cp protein from the amino acid sequence, and the 28-kDa protein may have been the Cs-cp mature protein.

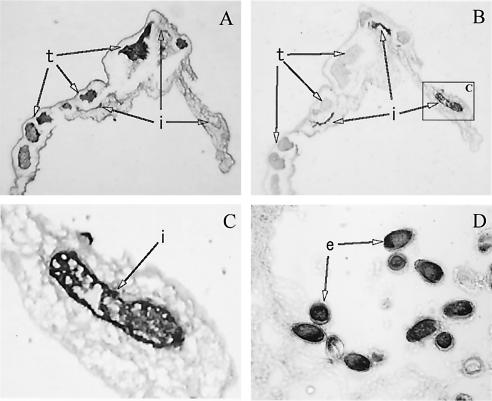

Cytolocalization of Cs-cp protein in C. sinensis adult worms.

Intense staining with the sera from mice immunized against the Cs-cp recombinant protein was found within the intestinal epithelial cells of the adult parasite and in the intrauterine eggs (Fig. 4). The tegumental surface and parenchymal tissues had no reaction. Normal mouse sera did not result in any positive reaction (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

(B to D) Immunocytochemical staining of C. sinensis adult worms with sera from mice immunized against the Cs-cp recombinant protein. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of C. sinensis adult worms. Abbreviations: i, intestine; e, intrauterine egg; t, testis.

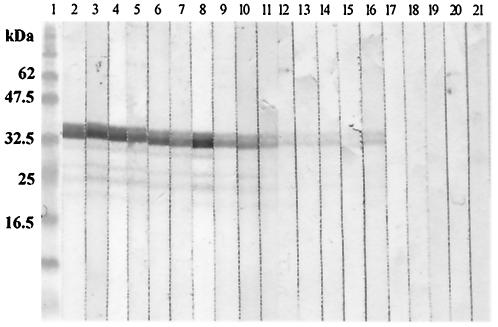

Cross-reactivity analysis of Cs-cp recombinant proteins by Western blotting.

The sera from patients infected with C. sinensis strongly reacted with the Cs-cp recombinant protein (Fig. 5, lanes 2 to 11), and the sera from patients infected with S. japonicum weakly reacted with the Cs-cp recombinant protein (Fig. 5, lanes 12 to 16), but sera from healthy persons did not react with the Cs-cp recombinant protein (Fig. 5, lanes 17 to 21).

FIG. 5.

Western blotting analysis of Cs-cp recombinant protein stained with sera from patients infected with C. sinensis (lanes 2 to 11), with sera from patients infected with S. japonicum (lanes 12 to 16), and with sera from healthy persons (lanes 17 to 21). Lane 1, molecular mass standards (masses shown on the left side).

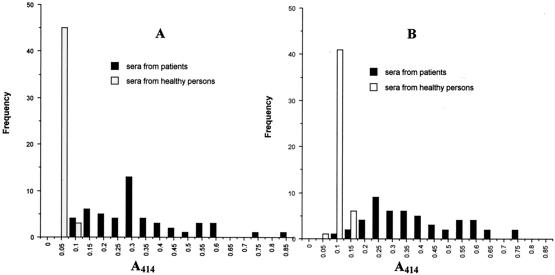

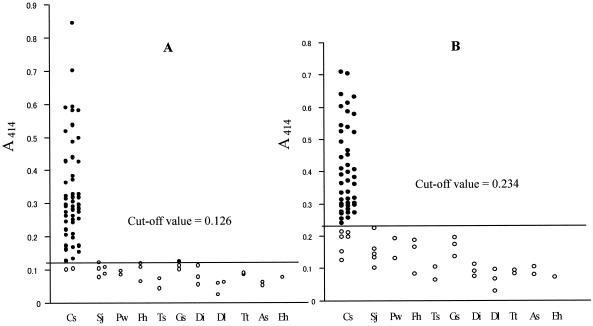

ELISA with human sera.

ELISA plates were sensitized by the Cs-cp recombinant protein and adult worm crude extracts, respectively, and then probed with human sera. The frequency distribution of positive and negative control sera was plotted as a histogram (Fig. 6). The A414 mean value of the negative control group for the Cs-cp antigen was 0.042 with a standard deviation of 0.007, while the A414 mean for adult worm extracts was 0.078 with a standard deviation of 0.017. The A414 means plus 3 standard deviations were 0.063 for the Cs-cp antigen and 0.129 for adult worm extracts, and three times the A414 means were 0.126 for the Cs-cp antigen and 0.234 for adult worm extracts. Since three times the A414 means were larger than the means plus 3 standard deviations, three times the A414 mean of the negative control group was determined as the cutoff value in further experiments, resulting in 0.126 for the Cs-cp antigen and 0.234 for adult worm extracts. The A414 mean and standard deviation of sera from patients infected with C. sinensis were 0.331 ± 0.160 for the Cs-cp antigen and 0.386 ± 0.147 for adult worm extracts. The sensitivities of the test using Cs-cp antigen and adult worm extracts were 96% (48 of 50) and 88% (44 of 50), respectively (Fig. 7). The specificity of this test was analyzed by measuring the reactivity of sera from 26 patients infected with other parasites. Only one sample from a patient with G. spinigerum infection produced a positive reaction when the Cs-cp antigen was used, while adult worm extracts showed no cross-reaction.

FIG. 6.

Immunoreactivity of the Cs-cp recombinant protein (A) and C. sinensis adult worm extracts (B). Analysis by ELISA of 50 sera from patients infected with C. sinensis and 48 sera from healthy persons. The y axis shows the frequency of absorbance measurements.

FIG. 7.

Comparison of reactivity in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of the Cs-cp recombinant protein (A) and C. sinensis adult worm extracts (B) against those of sera from patients infected with C. sinensis (Cs), S. japonicum (Sj), P. westermani (Pw), F. hepatica (Fh), T. solium (Ts), G. spinigerum (Gs), D. immitis (Di), D. latum (Dl), T. trichiura (Tt), A. simplex (As), and E. histolytica (Eh). The cutoff values are indicated by the long horizontal lines. Open circles indicate values below the cutoff, and solid circles indicate values above the cutoff.

DISCUSSION

There is a need for a reliable diagnostic tool to solve the clinical and parasitological diagnosis problems in clonorchiasis. An immunodiagnostic method is a highly sensitive and early method to diagnose C. sinensis infections.

Cysteine proteinases are highly antigenic because parasitic trematodes continually release them into the host. Therefore, cysteine proteinases are possible diagnostic antigens. Reportedly, the acidic extracts of various developmental stages of C. sinensis (metacercariae and adult worms) have cysteine proteinase activity (17). The present experiment showed that a recombinant cysteine proteinase of C. sinensis (Cs-cp) ensured the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for serological diagnosis of clonorchiasis.

The amino acid sequence of the Cs-cp cysteine proteinase was less similar to the cathepsin L cysteine proteinases from P. westermani, S. japonicum, and F. hepatica. These data suggest that for serological diagnosis, the Cs-cp recombinant protein probably does not cross-react with sera from patients with P. westermani, S. japonicum, and F. hepatica infections. Indeed, in an ELISA, the Cs-cp recombinant protein did not cross-react with sera from patients with S. japonicum infection, and cross-reaction was observed in only one patient with G. spinigerum infection. On the contrary, adult worm extracts did not cross-react with all sera from patients with parasitic infections, but the sensitivity of the test using adult worm extracts was lower than that of Cs-cp antigen.

Cysteine proteinases from some trematodes were reported to localize in the intestine or in cercarial extracts or immature eggs (10, 13, 20), but immnocytochemical analysis of C. sinensis cysteine proteinases has not been reported. In this study, C. sinensis cysteine proteinases are localized in the intestinal epithelial cells of the adult parasite and in the intrauterine eggs. These cysteine proteinases are parts of the excretory-secretory products of C. sinensis and are mainly synthesized in the intestinal epithelia, secreted into the lumen, and have been shown to be highly antigenic in infected animals.

In C. sinensis, two kinds of cysteine proteinases have been reported (14, 15, 18). We preliminarily produced these two kinds of cysteine proteinases in the E. coli expression system and analyzed these recombinant cysteine proteinases by Western blotting. The sera from patients infected with C. sinensis strongly reacted with the Cs-cp recombinant protein but did not react with other kinds of recombinant cysteine proteinase. These data suggested that all of the cysteine proteinases of C. sinensis were not immunodominant and did not induce immunological reaction during infection.

In conclusion, it has been demonstrated that the recombinant cysteine proteinase is useful for immunodiagnosis of clonorchiasis by ELISA and will provide more reliable results not only for routine diagnosis but also for epidemiological surveys of clonorchiasis. Thus, the use of recombinant antigen may provide a new source of diagnostic reagent and more reliable results for diagnosis of clonorchiasis.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by a grant-in-aid from the Japan-China Medical Association.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carnevale, S., M. I. Rodriguez, E. A. Guarnera, C. Carmona, T. Tanos, and S. O. Angel. 2001. Immunodiagnosis of fasciolosis using recombinant procathepsin L cysteine proteinase. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 41:43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chappell, C. L., M. H. Dresden, B. Gryseels, and A. M. Deelder. 1990. Antibody response to Schistosoma mansoni adult worm cysteine proteinases in infected individuals. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 42:335-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colangeli, R., A. Heijbel, A. M. Williams, C. Manca, J. Chan, K. Lyashchenko, and M. L. Gennaro. 1998. Three-step purification of lipopolysaccharide-free, polyhistidine-tagged recombinant antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 714:223-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordova, M., L. Reategui, and J. R. Espinoza. 1999. Immunodiagnosis of human fascioliasis with Fasciola hepatica cysteine proteinases. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:54-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornelissen, J. B., C. P. Gaasenbeek, F. H. Borgsteede, W. G. Holland, M. M. Harmsen, and W. J. Boersma. 2001. Early immunodiagnosis of fasciolosis in ruminants using recombinant Fasciola hepatica cathepsin L-like protease. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:728-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crompton, D. W. 1999. How much human helminthiasis is there in the world? J. Parasitol. 85:397-403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalton, J. P., K. A. Clough, M. K. Jones, and P. J. Brindley. 1996. Characterization of the cathepsin-like cysteine proteinases of Schistosoma mansoni. Infect. Immun. 64:1328-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillyer, G. V., and E. A. Serrano. 1983. The antigens of Paragonimus westermani, Schistosoma mansoni, and Fasciola hepatica adult worms. Evidence for the presence of cross-reactive antigens and for cross-protection to Schistosoma mansoni infection using antigens of Paragonimus westermani. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 32:350-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeda, T., Y. Oikawa, and T. Nishiyama. 1996. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using cysteine proteinase antigens for immunodiagnosis of human paragonimiasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 55:435-437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang, S. Y., M. S. Cho, Y. B. Chung, Y. Kong, and S. Y. Cho. 1995. A cysteine protease of Paragonimus westermani eggs. Korean J. Parasitol. 33:323-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klinkert, M. Q., K. Bommert, D. Moser, R. Felleisen, G. Link, O. Doumbo, and E. Beck. 1991. Immunological analysis of cloned Schistosoma mansoni antigens Sm31 and Sm32 with sera of schistosomiasis patients. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 42:319-324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuda, H., H. Tanaka, B. L. Bayani, N. S. Julian, T. Tokawa, and S. Ohsawa. 1984. Evaluation of ELISA with ABTS, 2-2′-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonic acid), as the substrate of peroxidase and its application to the diagnosis of schistosomiasis. Jpn. J. Exp. Med. 54:131-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michel, A., H. Ghoneim, M. Resto, M. Q. Klinkert, and W. Kunz. 1995. Sequence, characterization and localization of a cysteine proteinase cathepsin L in Schistosoma mansoni. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 73:7-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Na, B. K., H. J. Lee, S. H. Cho, H. W. Lee, J. H. Cho, W. G. Kho, J. S. Lee, J. S. Lee, K. J. Song, P. H. Park, C. Y. Song, and T. S. Kim. 2002. Expression of cysteine proteinase of Clonorchis sinensis and its use in serodiagnosis of clonorchiasis. J. Parasitol. 88:1000-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park, S. Y., K. H. Lee, Y. B. Hwang, K. Y. Kim, S. K. Park, H. A. Hwang, J. A. Sakanari, K. M. Hong, S. I. Kim, and H. Park. 2001. Characterization and large-scale expression of the recombinant cysteine proteinase from adult Clonorchis sinensis. J. Parasitol. 87:1454-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rim, H. J. 1986. The current pathology and chemotherapy of clonorchiasis. Korean J. Parasitol. 24(Suppl.):78-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song, C. Y., and A. A. Rege. 1991. Cysteine proteinase activity in various developmental stages of Clonorchis sinensis: a comparative analysis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 99:137-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song, C. Y., M. H. Dresden, and A. A. Rege. 1990. Clonorchis sinensis: purification and characterization of a cysteine proteinase from adult worms. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 97:825-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Heijne, G. 1986. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:4683-4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamasaki, H., E. Kominami, and T. Aoki. 1992. Immunocytochemical localization of a cysteine protease in adult worms of the liver fluke Fasciola sp. Parasitol. Res. 78:574-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamasaki, H., R. Mineki, K. Murayama, A. Ito, and T. Aoki. 2002. Characterisation and expression of the Fasciola gigantica cathepsin L gene. Int. J. Parasitol. 32:1031-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yun, D. H., J. Y. Chung, Y. B. Chung, Y. Y. Bahk, S. Y. Kang, Y. Kong, and S. Y. Cho. 2000. Structural and immunological characteristics of a 28-kilodalton cruzipain-like cysteine protease of Paragonimus westermani expressed in the definitive host stage. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7:932-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]