Abstract

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) is a characteristic syndrome in which the Mullerian structures are absent or rudimentary. It is also associated with anomalies of the genitourinary and skeletal systems. Its association with gonadal dysgenesis is extremely rare and appears to be fortuitous, independent of chromosomal anomalies. We report such a case in a 21-year-old girl who presented primary amenorrhea and impuberism. The endocrine study revealed hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism. The karyotype was normal, 46, XX. No chromosome Y was detected at the fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis. Internal genitalia could not be identified on the pelvic ultrasound and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging. Laparoscopy disclosed concomitant ovarian dysgenesis and MRKH syndrome. There were no other associated malformations. Hormonal substitution therapy with oral conjugated estrogens was begun. The patient has been under regular follow-up for the last two years and is doing well.

Keywords: Gonadal dysgenesis, karyotype, Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Gonadal dysgenesis with female phenotype is defined as a primary ovarian defect leading to premature ovarian failure in otherwise normal 46, XX females as a result of failure of the gonads to develop or due to resistance to gonadotropin stimulation. It causes primary amenorrhea with variable hypogonadism or impuberism, depending on the degree of gonadal development.[1]

The Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome is a specific type of Mullerian duct malformation characterized by congenital absence or hypoplasia of uterus and upper two thirds of the vagina in both phenotypically and karyotypically normal females with functional ovaries. It is the second most common cause of primary amenorrhea after gonadal dysgenesis.[1]

An association between these two conditions is extremely rare and appears to be fortuitous. We report such a case in a 21-year-old girl with a 46, XX karyotype.

CASE REPORT

We report the case of a 21-year-old girl who presented primary amenorrhea and impuberism. There was no family history of consanguinity, miscarriages, neonatal deaths, or other members with primary amenorrhea. The woman was born from a normal pregnancy and eutocia. Her medical history was unremarkable. Her height was 168 cm, weight was 54 Kg, and blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg. Breast development was at Tanner stage I, and pubic and axillary hair were at Tanner stage II. The patient had no evidence of facial dysmorphism, webbing of the neck, or skeletal abnormalities.

Gynecologic examination revealed a 1-cm vaginal blind pouch. Female external genitalia were normal. No uterus was palpable on rectal examination.

The blood count, standard biochemical parameters, and urinalysis were within the normal range. An endocrine study including pituitary, ovarian, and thyroid evaluation was performed and revealed hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism (Luteinizing Hormone: 23 UI/l, Follicle-stimulating Hormone: 55 UI/l, Oestradiol: 10 pg/ml) with normal level of prolactin and Thyroid-stimulating Hormone. The karyotype was 46, XX, and no Y chromosome material was detected in fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

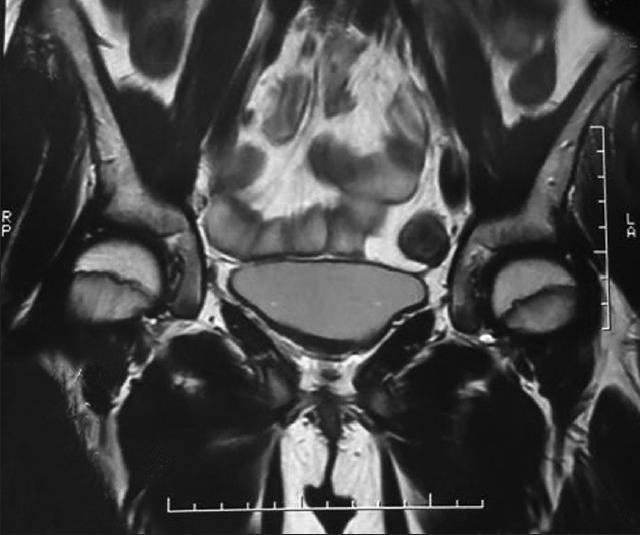

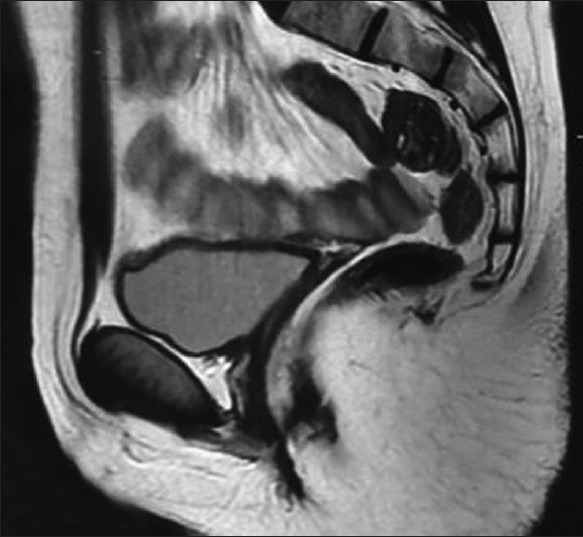

Internal genitalia could not be identified on the pelvic ultrasound on the magnetic resonance imaging [Figures 1 and 2]. Internal genitalia could not be identified on the pelvic ultrasound and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (Q1).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging: Axial plane cut showing bladder and rectum without interposition of uterus

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging examination sagittal plane cut showing absence of uterus and ovaries

Laparoscopy was undertaken and disclosed absence of gonads, fallopian tubes, and uterus [Figure 3]. The diagnosis of ovarian dysgenesis associated with MRKH syndrome was made. Hormonal substitution therapy with oral conjugated estrogens was begun.

Figure 3.

Laparoscopic view showing absence of gonads, fallopian tubes, and uterus

Bone study, pelvic ultrasound, and laparoscopic study were ordered to evaluate the associated genitourinary and skeletal anomalies. There were no other morphological malformations.

Hormonal substitution therapy with oral conjugated estrogens was begun. Two years afterward, the patient showed a Tanner 3 breast stage.

DISCUSSION

Our patient had two anomalies affecting reproductive performance, 46, XX gonadal dysgenesis and MRKH.

46, XX gonadal dysgenesis is a primary ovarian defect leading to premature ovarian failure in otherwise normal 46, XX females due to failure of the gonads to develop or resistance to gonadotropin stimulation. Prevalence is unknown but is thought to be less than 1/10.000. Patients are born as females without ambiguity. However, affected individuals present during adolescence or young adulthood with either delayed or absent puberty resulting in primary or sometimes secondary amenorrhea. The internal and external genitalia are normally developed. Although the underlying etiology of ovarian dysgenesis remains unknown in most cases, several genes have been implicated including homozygous or compound heterozygous inactivating mutations of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene (FSHR), mutations in the BMP15 gene, and mutations in the NR5A1 gene.[2,3,4,5,6]

MRKH syndrome is characterized by Müllerian duct structures agenesis, vaginal atresia, rudimentary or absent uterus with normal ovaries and Falloppian tubes in females normal from a genetic (46 XX), phenotypic and developmental features. The prevalence has been reported as 1 in 4.500 female births.[7]

Some authors classify this syndrome in 2 types: Type A (typical syndrome) is characterized by absence of both the vagina and uterus, leaving only symmetric uterine remnants, normal fallopian tubes, and ovaries; type B (atypical syndrome) usually shows asymmetric or absent uterine remnants, hypoplasia, or aplasia of one or both fallopian tubes, and frequent associated anomalies.[1] Upper urinary tract malformations are found in about 40% of cases, including unilateral renal agenesis, renal ectopia/hypoplasia, horseshoe kidney, and hydronephrosis. Skeletal and cardiac anomalies, auditory defects, and anorectal malformations were also reported.[7]

Thus, all patient with MRKH syndrome should undergo instrumental examinations (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance, urography) to find out the possible anomalies associated. The laparoscopy is the last chance and usually gives the confirmation and classification of MRKH.[7] In our case, we ruled out associated renal and skeletal anomalies by bone study, pelvic ultrasound, and laparoscopic study, and our patient was diagnosed as having the typical MRKH syndrome.

The etiology of MRKH syndrome is unknown but it is believed that embryological development is interrupted during the sixth or seventh week of gestation. Since the mesonephros (which give rise to kidneys), the Mullerian ducts, and the skeleton all originate from the mesoderm, it is believed that a deleterious event occurs during this phase of gestation, giving rise to the abnormalities seen in the MRKH syndrome.[8]

The increased number of cases in familial aggregates raises the hypothesis of a genetic cause.[9] Autosomal dominant trait with an incomplete degree of penetrance and variable expressivity is most likely mode of transmission.[7]

Estrogens may influence development of the Mullerian ducts. Absence of anti-Mullerian hormone is also essential for its development. The existence of activating mutations of either the gene for the anti-Mullerian hormone or the gene for the anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, and the lack of estrogen receptors during embryonic development have been hypothesized to cause MRKH syndrome.[1]

The association of gonadal dysgenesis with Mullerian tract anomalies is extremely rare. It was first described by McDonough et al. in a girl with gonadal dysgenesis, duplication of the Mullerian duct system, and a 46, XX karyotype.[10] The coexistence of these two anomalies was then reported in patients with 45, X, 45, X/46, XX, 46, XX, 46, XY, 45, X/46, Xdic (X), 46, Xi (Xq), 45, X/46, X, del (X) (p11.21), and 46, X, del (X)(pter → q22:) karyotypes.[1,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] This finding suggests that the occurrence of neither this association nor Mullerian tract anomalies alone is not related with a specific chromosomal abnormality.[17]

Theoretically, an undifferentiated gonad could produce anti-Mullerian hormone in earlier embryologic period, leading to a subsequent regression. But this hypothesis cannot be valuable without the presence of the chromosome Y.[1] The FISH analysis of karyotype of our patient demonstrated the absence of chromosome Y.

Hormone substitution therapy remains the only therapeutic option. It is aimed at triggering the development of secondary sexual characters and prevent osteoporosis. There remains the unsolved problem of infertility.[1]

CONCLUSION

The association of gonadal dysgenesis and MRKH syndrome is extremely rare and appears to be fortuitous, independent of chromosomal anomalies. These two conditions compromise the fertility both in the mechanic and hormonal way. Hormone substitution therapy remains the only therapeutic option. The latter is aimed at triggering the development of secondary sexual characters and prevent osteoporosis. Unfortunately, there remains the unsolved problem of infertility.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Gorgojo JJ, Almodóvar F, López E, Donnay S. Gonadalagenesis 46, XX associated with the atypicalform of Rokitansky syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:185–7. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02943-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heufelder AE. Gonads in trouble: Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene mutation as a cause of inherited streak ovaries. Eur J Endocrinol. 1996;134:296–7. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1340296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aittomäki K, Lucena JL, Pakarinen P, Sistonen P, Tapanainen J, Gromoll J, et al. Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptorgene causes hereditaryhypergonadotropicovarianfailure. Cell. 1995;82:959–68. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lourenço D, Brauner R, Lin L, De Perdigo A, Weryha G, Muresan M, et al. Mutations in NR5A1 associated with ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1200–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferraz-de-Souza B, Lin L, Achermann JC. Steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1, NR5A1) and human disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;336:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledig S, Röpke A, Haeusler G, Hinney B, Wieacker P. BMP15 mutations in XX gonadaldysgenesis and prematureovarianfailure. (e1-5).Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:84. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rampone B, Filippeschi M, Di Martino M, Marrelli D, Pedrazzani C, Grimaldi L, et al. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome presenting as vaginal atresia: Report of two cases. G Chir. 2008;29:165–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma S, Aggarwal N, Kumar S, Negi A, Azad JR, Sood S. Atypical Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome with scoliosis, renal and anorectal malformation-case report. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2006;16:809–12. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morcel K, Camborieux L. Programme de Recherchessur les Aplasies Müllériennes, Guerrier D. Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonough PG, Byrd JR, Freedman MA. Complete duplication and underdevelopment of the Müllerian system in association with gonadal dysgenesis. Report of a case. ObstetGynecol. 1970;35:875–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardo S, Papp Z, Gaal J. XO/XX mosaicism in the Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Lancet. 1971;2:1380–1. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong SL, Lippe BM, Kaplan SA. The XX Turner phenotype with unilateral streak gonad and absent uterus. Am J Dis Child. 1971;122:449–51. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1971.02110050119020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Check JH, Weisberg M, Laeger J. Sexual infantilism accompanied by congenital absence of the uterus and vagina: Case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;145:633–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)91209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Leon FD, Hersh JH, Sanfilippo JS, Schikler KN, Yen FF. Gonadal and Mullerian agenesis in a girl with 46, X, i (Xq) ObstetGynecol. 1984;63:81S–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guitron-Cantu A, Lopez-Vera E, Forsbach-Sanchez G, Leal-Garza CH, Cortes-Gutierrez EI, Gonzalez-Pico I. Gonadal dysgenesis and Rokitansky syndrome. A Case report. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:891–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ting TC, Chang SP. Coexistence of gonadal dygenesis and mullerian agenesis with two mosaic cell lines 45, X/46, X, del (X) (p22.2) Zhongua Yi XueZaZhi (Taipei) 2002;65:450–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aydos S, Tükün A, Bökesoy I. Gonadal dysgenesis and the Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome in a girl with 46, X, del (X)(pter->q22:) Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;267:173–4. doi: 10.1007/s00404-001-0274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]