Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Our objective was to study the presence of a characteristic appearance of metastatic disease to the gastrointestinal tract on contrast-enhanced CT in patients with known malignancies and to investigate its clinical implications.

CONCLUSION

Twenty-five patients with scirrhous metastases had a malignant CT target sign. Careful observation and correlation with clinical history are required to differentiate this unique sign from a benign target sign.

Keywords: colon, CT, intestine, scirrhous metastases

The target sign was first described by Balthazar [1] as a series of three concentric high-, low-, and high-attenuation layers of the intestinal wall at contrast-enhanced CT. One of the great utilities of this sign is that it reflects a histologically benign condition resulting in expansion of the submucosal layer of the intestinal wall by edema, inflammatory infiltration, blood products, or fat.

We have noted a slightly different target appearance in some of our oncologic patients with metastatic disease. The target signs described in our experience have primarily been in the colon in patients with gastric cancer metastases. The bowel wall in these cases shows thickened hyperattenuating outer and inner layers and a hypoattenuating thin intervening layer. This appearance differs from the classic target sign by its narrower intervening layer (Fig. 1) and shorter, more segmental bowel wall involvement in patients with scirrhous metastases.

Fig. 1. Benign and malignant target sign.

A and B, Schematic diagrams show high-attenuation bowel wall layers (white) in benign target sign (A) and malignant target sign (B). For benign sign, low-attenuation intermediate layer (star, A) represents submucosal edema. Outer layers represent normal or inflamed mucosa (inner layer) and muscularis propria and serosa (outer layer). For malignant sign, intermediate layer (star, B) represents muscularis propria with less tumor infiltration and enhancement. In the malignant target sign the infiltrated and hyperenhancing mucosa and submucosa (inner layer) and serosa (outer layer) are thickened. Central area represents lumen.

To further investigate this malignant target sign, we surveyed all patients with an extracolonic primary malignancy who underwent endoscopic or radiologic investigation. Our purpose was to record how often this particular characteristic appearance of metastatic disease to the gastrointestinal tract on contrast-enhanced CT was noted and to investigate its clinical implications.

Materials and Methods

To construct our patient population, we retrospectively searched several patient databases. A search of our hospital discharge diagnosis database was performed for all patients with primary tumors known to result in scirrhous metastases (breast, gastric, and bladder cancer) who underwent barium enema imaging from 1997 until June 2007 (n = 582). A database of patients who underwent endoscopic colon stenting for malignant strictures between February 2002 and July 2006 was also searched (n = 49) in addition to another database of patients with primary noncolorectal cancer who underwent barium enema imaging or colonoscopy from January 1997 to June 2007. From this latter database, all patients with International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes indicating metastatic disease to the colon (197.5) or metastases to the gastrointestinal tract (197.8) (or both) or metastases to the small intestine (197.4) were evaluated (n = 76). The combined databases resulted in 667 unique patients. In 509 patients, at least one contrast-enhanced CT study was available for review. Our final study group consisted of 2,813 contrast-enhanced CT studies in 509 patients. A waiver for patient consent was granted in this institutional review board–approved retrospective study.

All CT scans were reinterpreted in consensus by one attending radiologist and one second-year radiology resident for the presence of a target appearance of the intestines consisting of a low-attenuation intermediate layer surrounded by higher-attenuation outer and inner layers. The low-density intermediate layer had to be of equal or lesser thickness than either one or both of the adjacent hyperattenuated layers.

Only IV contrast-enhanced CT scans were included. During the years searched, our department used single-detector CT and 4-, 8-, or 16-MDCT helical scanners. Patients received 150 mL of iodinated contrast material (45 g I) unless they had elevated creatinine, in which case they received 100 mL (30 g I). Oral contrast material was the standard but was not uniformly used in very ill or uncooperative patients. Slice thickness varied from 3.75 to 10 mm.

In addition to demographic patient information, we recorded primary neoplasm, segments of intestine involved, maximal length (centimeters) and width (outer wall to outer wall in centimeters) of the target appearance, presence of intestinal obstruction (defined as proximal intestinal dilatation and identification of a point of transition to distal smaller-caliber intestinal loops), other metastatic sites, histology of lesion, operative and PET findings, time from diagnosis of primary lesion, treatment of intestinal metastases, and survival from time of appearance of target lesion. The reference standard could be histology, visual appearance at surgery or colonoscopy, or PET uptake in the same regions as the CT target sign.

Results

Clinical and Epidemiologic Factors

Twenty-five (5%) of 509 patients (14 women and 11 men) with a mean age of 60 years (age range, 38–79 years) showed 40 malignant CT target signs on 87 contrast-enhanced CT studies (36 colorectal, two small intestinal, and two esophageal). Pathologically proven known primary malignancies consisted of 12 gastric, seven bladder, and five breast cancers and one patient with an unknown primary malignancy. The average time to the appearance of the malignant target sign on CT from the time of primary malignancy diagnosis was 90 months (range, 1–228 months; median, 29.0 months). Among 18 patients who were deceased at the time of chart review, the average survival time from the appearance of the malignant target sign was 10.3 months (range, < 1 month to 42 months; median, 5 months).

Nineteen (76%) of these 25 patients had documented metastatic disease at or before the time of diagnosis of the malignant target sign as follows: peritoneal carcinomatosis (n = 18); bone metastases (n = 3); liver metastases (n = 2); and one each of metastases to the abdominal wall, prostate, scrotum, ovaries, lungs, and pleura. There were two local recurrences: one gastric and one bladder, and one patient had malignant ascites but no masses. Some patients had metastases to more than one anatomic site.

Treatment of strictures associated with the malignant target signs included placement of stents (rectal [n = 5] and left colon [n = 1]), endoscopic dilatation (esophageal [n = 2] and splenic flexure [n = 1]), chemotherapy (n = 4), colostomy (n = 2), colectomy (n = 3), enterectomy (n = 2), and one each of ileostomy and radiation therapy and percutaneous gastrostomy drainage for end-stage small-bowel obstruction. No treatment was administered in eight patients, of whom five died, one was lost due to transfer of care elsewhere, and two are alive at the time of this writing.

Reference Standard

Histologically proven bowel metastases were present in 11 (44%) of 25 patients. Six endoscopic and one exploratory laparotomy biopsies showed carcinoma emboli in rectal mucosal lymphatics (n = 2); poorly differentiated metastases involving mucosa, muscularis mucosa, and submucosa of the large intestinal wall (n = 3) (Figs. 2 and 3); and signet ring metastases involving the large (n = 1) and large and small intestine (n = 1). Partial colectomy in four patients showed metastatic signet ring carcinoma (n = 2, one full-thickness and one serosa) and metastatic lobular breast carcinoma (n = 2).

Fig. 2.

Photograph of section of colon shows tumor infiltration into mucosa (long black arrow), submucosa (short black arrow), muscularis propria (white arrow) and subserosa (arrowhead) (see Figure 5A).

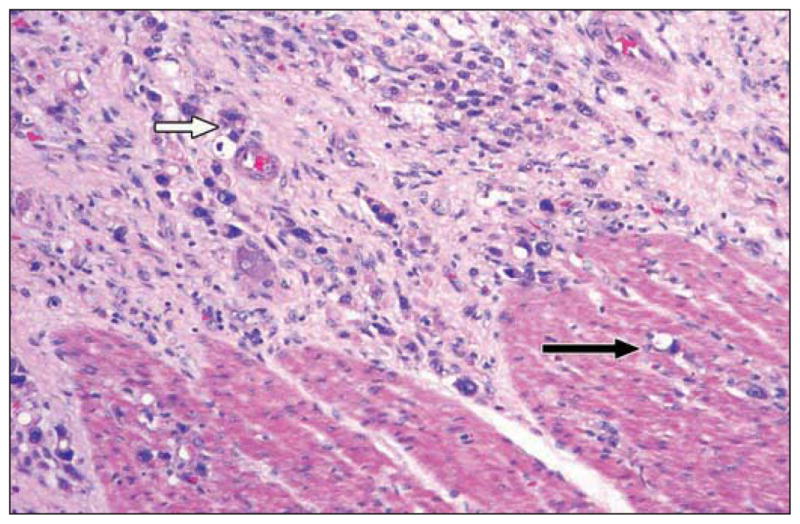

Fig. 3.

High-magnification photomicrograph from different specimen shows tumor infiltrating submucosa (white arrow) and fewer cells in muscularis propria (black arrow) (see Figure 4A).

In seven (28%) of 25 patients, visual confirmation of metastases was present. In five patients, the colonoscopic findings included “circumferential wall thickening or malignant-appearing stricture” (n = 3) and high-grade malignant obstruction or obstructing extrinsic mass (n = 2). In the remaining two patients, visual confirmation of tumor was made at laparotomy (n = 1) and at laparoscopy (n = 1).

In seven (28%) of 25 patients, lesions were diagnosed presumptively. Five patients had extensive metastatic disease, including in the peritoneum. Four of these patients had intestinal obstruction proximal to the target lesion. One patient had a sigmoid colon metastasis resected 18 months earlier and later underwent placement of a percutaneous drainage gastrostomy tube for end-stage intestinal metastases. The remaining two patients had focal 18F-FDG uptake in the exact location of the malignant target sign seen on CT.

Radiologic Findings

CT

In 16 patients, the rectum was involved (Fig. 4). In 13 patients, other parts of the colon were involved (multiple sites, n = 12) (Fig. 5). In two patients, the small intestine was involved (Fig. 6). Two patients had esophageal involvement. The mean overall length of gastrointestinal wall involvement was 9.1 cm (range, 1–50 cm). The mean overall width of gastrointestinal wall involvement was 3.5 cm (range, 2.0–5.7 cm). The mean length of colorectal involvement was 5.7 cm (range, 1.0–12.0 cm. The mean width of the colorectal wall was 4.0 cm (range, 2.0–5.7 cm). The mean length and width of small-bowel involvement were 50.0 and 3.2 cm, respectively. Both small-bowel cases had extensive involvement, each estimated at about 50.0 cm. The mean length and width of esophageal involvement were 3.2 and 2.8 cm, respectively. Intestinal obstruction was present in 16 patients (large, n = 11; small, n = 2; both, n = 3). In 11 of 25 patients, the malignant target sign was the first indication of intestinal metastases. This usually occurred in patients with rectal involvement (n = 9) or other portions of colon (n = 2). In other cases, known metastatic disease preceded a recognizable malignant CT target sign.

Fig. 4. Malignant target sign involving rectum.

A, CT image in 67-year-old woman with gastric cancer shows intermediate low-density layer (arrow).

B, CT image in 73-year-old woman with bladder cancer.

C, CT image in 76-year-old woman with gastric cancer.

Fig. 5. 67-year-old woman with gastric cancer and multifocal colon metastases.

A, Longitudinal CT image shows transverse colon malignant target sign. Note that anterior wall is incompletely imaged in this plane. Posterior wall shows hyperattenuated serosa (short arrow), hypoattenuated muscularis mucosa (long arrow), and thickened hyperattenuated submucosa and mucosa (curved arrow).

B, Axial CT image of transverse colon malignant target sign. Outer hyperattenuated layer is irregular and thinner and thickens on later scans. Finding was seen several times, suggesting that it occurs after inner layer thickening.

C, CT image of right colon benign target sign of edema from ischemia proximal to obstructing transverse colon involvement. Note different pattern of target with markedly thickened low-attenuation submucosa (curved arrow) and thin mucosa and serosa (straight arrows) compared with A and B.

Fig. 6.

39-year-old woman with gastric cancer metastases to small bowel and peritoneum. Note two loops of small bowel that show very clear malignant target sign (arrows).

PET

Findings at PET performed in six patients around the time of discovery of intestinal metastases revealed evidence of metastatic disease to the gastrointestinal tract as follows: rectum (n = 2; one intense and one with standardized uptake value [SUV] of 3.4), colon (n = 3; two at a single site and one multi-focal; SUV, 5.0–6.1), and esophagus (n = 1; SUV, 7.7) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Metastatic disease in mid transverse colon.

A–C, Scans from 18F-FDG PET (A), unenhanced CT (B), and IV contrast-enhanced CT (C) show focus of metastatic disease in mid transverse colon (arrow).

Discussion

Scirrhous-type intestinal metastases (also known as linitis plastica–type) originate from primary tumors such as breast, gastric, lung, and pancreaticobiliary carcinomas. They may appear more infiltrative and less masslike. They can be subtle and even masquerade as benign strictures. They may be clinically occult until involvement is severe [2, 3].

In an autopsy series, Fernet et al. [4] described seven cases of intestinal metastases from gastric carcinoma. The neoplastic infiltrate was present on the serosal side or submucosal region but with “no significant invasion, replacement, or compression of the muscularis as usually seen in ordinary metastatic carcinoma.”

On barium studies, scirrhous metastases show smooth-appearing strictures in the small and large intestine. These must be interpreted with greater caution because they can appear benign. Furthermore, appearances at endoscopy also can be misleading, especially in the absence of mucosal disruption. Biopsies may be negative if not sampled deeply enough [3].

The literature on the CT appearance of scirrhous intestinal metastases is scant [5, 6]. Balthazar et al. [5] reported 31 cases of primary scirrhous carcinoma at CT in 1995. In these cases, the primary tumors of the stomach and colon were of mostly homogeneous attenuation with only two cases exhibiting a target appearance. Advanced disease was present in 93%, attesting to the marked aggressiveness of scirrhous carcinoma.

Recently, features of metastatic linitis plastica to the rectum have been described [6]. In this series of 22 patients, six (27%) showed a target pattern consisting of hyperattenuated inner and outer layers and a hypoattenuated intermediate layer. The remaining lesions showed uniform, marked enhancement of the rectum. In this series as in ours, most patients had other metastatic disease, including ascites and peritoneal thickening.

In some of our patients, metastatic disease to the intestines presented as intestinal obstruction, even requiring stents. In other patients, probably because of routine oncologic surveillance, a malignant target sign preceded symptoms. Patients who survived long enough, however, usually went on to clinical obstruction requiring surgical bypass or stenting.

The target sign we describe is distinctly different both in appearance and in pathophysiology from that originally defined by Balthazar [1]. In the malignant target sign, as explained by Ha et al. [6] and as shown in our histologic samples (Figs. 2 and 3), tumor infiltrates all layers of the intestinal wall but expands the mucosa, submucosa, and serosa much more than the muscularis propria as a result of the looser nature of these layers compared with the more tightly packed muscle cells of the muscularis propria. Therefore, the muscularis propria is the least thickened layer and the least hyperattenuating [6]. In the classic target sign, edema from many possible causes expands the submucosa, increasing its width and lowering its density [1]. Furthermore, this low-density layer tends to be the most prominent of all the layers in the classic target sign.

In our study the target sign length and width added little information. We suspect that the short lengths we found would be uncommon for a benign target sign. The length may also assist the endoscopist in planning for stent placement. More helpful when considering the differential diagnosis was the multifocality of disease, which would argue more in favor of metastatic disease.

The malignant target sign consistently showed disproportionate thickening of the hyperattenuated outer and inner layers to the intermediate hypoattenuated layer, irrespective of the segment of the gastrointestinal tract involved. We believe this signifies the robustness and reliability of the sign. At times, the malignant target sign converted to homogeneous thickening of the intestinal wall with loss of the central low attenuation. It is unclear if this was related to progression of disease, quality of the IV contrast bolus, or other technical features, but in no case did the segment ever regain a normal appearance.

The malignant target sign is not a requisite appearance for scirrhous intestinal metastases, and other patterns may be seen. IV contrast enhancement is necessary for its recognition. Although our results do not allow us to say this sign is pathognomonic for metastases, in our experience, it is highly suggestive in the proper clinical scenario.

The clinical utility of the malignant target sign on CT therefore appears to be threefold: it may be the first indication of intestinal metastatic disease in advance of symptoms or obstruction; it portends a poor long-term prognosis; and, although the appearance is similar to the well-described benign target sign, careful observation and knowledge of the clinical history will allow radiologists to distinguish it as a sign heralding metastatic disease.

There are some limitations to this study. We actively searched for patients with gastric, breast, and bladder cancer, which represents a preselection bias to our methodology. Although we also used a database of patients with all noncolorectal primary malignancies, we only included those with proven bowel metastases rather than actively screening all patients. We may have overlooked cases because the numerous body CT radiologists interpreting our studies may not have recognized them. We did not include primary scirrhous colon cancer in this report. This rare entity might be in the differential diagnosis; however, patient history should help define the diagnosis. Finally, histologic proof of metastatic disease was only available in 44% of our patients.

In conclusion, the malignant target sign may be seen, most typically in the rectum or other parts of the colon and occasionally other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, in patients with metastatic disease from scirrhous-type primary lesions such as gastric, breast, and bladder cancers. When encountered in patients with these known primary neoplasms, we think that this appearance should be considered highly suspicious for metastasis and that close follow-up for development of bowel obstruction is warranted. Negative endoscopic biopsies should be interpreted with caution, and further investigation should be undertaken.

References

- 1.Balthazar EJ. CT of the gastrointestinal tract: principles and interpretation. AJR. 1991;156:23–32. doi: 10.2214/ajr.156.1.1898566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyers MA. Dynamic radiology of the abdomen: normal and pathologic anatomy. 5. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2000. Intraperitoneal spread of malignancies; pp. 131–255. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balthazar EJ, Rosenberg HD, Davidian MM. Primary and metastatic scirrhous carcinoma of the rectum. AJR. 1979;132:711–715. doi: 10.2214/ajr.132.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernet P, Azar HA, Stout AP. Intramural (tubal) spread of linitis plastica along the alimentary tract. Gastroenterology. 1965;48:419–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balthazar EJ, Siegel SE, Megibow AJ, Scholes J, Gordon R. CT in patients with scirrhous carcinoma of the GI tract: imaging findings and value for tumor detection and staging. AJR. 1995;165:839–845. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.4.7676978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha HK, Jee KR, Yu E, et al. CT features of metastatic linitis plastica to the rectum in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. AJR. 2000;174:463–466. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.2.1740463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]