Abstract

The effects on children of political violence are matters of international concern, with many negative effects well-documented. At the same time, relations between war, terrorism or other forms of political violence and child development do not occur in a vacuum. The impact can be understood as related to changes in the communities, families and other social contexts in which children live, and in the psychological processes engaged by these social ecologies. To advance this process-oriented perspective, a social ecological model for the effects of political violence on children is advanced. This approach is illustrated by findings and methods from an ongoing research project on political violence and children in Northern Ireland. Aims of this project include both greater insight into this particular context for political violence and the provision of a template for study of the impact of children’s exposure to violence in other regions of the world. Accordingly, the applicability of this approach is considered for other social contexts, including (a) another area in the world with histories of political violence, and (b) a context of community violence in the US.

The effects on children of political violence are matters of international concern. However, relations between war, terrorism or other political violence and child development are unlikely to follow a political, military, or related level of analysis. The impact is a function, in part, of changes initiated in the communities, families and other social contexts in which children live, and in the psychological processes engaged by the social ecology of political violence. Thus, in order to understand better relations between political violence and child development it is important to investigate the effects due to multiple levels of societal functioning, including community and domestic conflict and psychological processes associated with exposure to conflict and violence (Feerick & Prinz, 2003a; Prinz & Feerick, 2003a).

Over time, the links between political violence and children’s functioning are likely to be bidirectional, with children’s functioning and development being a critical component of a sustained peace.. This level of understanding thus is relevant to advances in long-term political conflict resolution. For example, peace accords and political agreements may fail to ameliorate the deleterious effects of conflicts from the perspectives of children or the communities in which children live (Darby, 2006). If children maintain historical animosities towards others in their cultures, solutions agreed upon between political leaders may be short-term and fragile (Cairns & Roe, 2003). Children are not only observers or recipients of political violence but may be at the forefront of political change (Leavitt & Fox, 1993). The perceptions, behaviors and emotions between groups, including the children, must change for achievement of lasting peace.

At the same time, in order to know whether these processes have changed for the better or remain problematic, one must be able to characterize the nature of these processes, and assess their status in the context of cultures in conflict over time. If problems remain, a next step is to design interventions informed by this knowledge to change destructive tendencies in the culture and among the children. Understanding and the resolution of conflicts at multiple levels of societal functioning is needed to facilitate peace in regions of historical and long-standing cultural, ethnic, and community conflict and violence.

There are increasing concerns about the effects on children of exposure to political, community and domestic violence, as reflected by the NIH initiative on Children Exposed to Violence (NIH, 2003, PAR-03-096). However, little systematic study has been accomplished on the implications of the interrelations between these factors for the well-being and development of children. The mechanisms by which political (often ethnic) conflict and community violence (both intra, i.e., criminal, and inter, i.e., sectarian) relate to the family, and, in turn, children’s well-being and development are even less well-understood. More also needs to be understood about bidirectional relations between political violence and children’s functioning, including the associations between children’s attitudes and behaviors in these contexts and family, community and political conflict and violence. There are many gaps, including need for theory-driven research, innovative study designs and approaches to measurement, consideration of multiple influences and complex ecological processes, and sophisticated analytic methods (Cairns, 1996; Feerick & Prinz, 2003b; Prinz & Feerick, 2003b).

With regard to these issues, the present paper advances an ecological framework for conceptualizing the impact of political violence on children, informed by theories about the effects of conflict and violence on children, and including multiple new directions in measurement, assessment of social ecological influences, and advanced analytic approaches. Moreover, this approach is illustrated by findings and methods from an ongoing research project on political violence and children in Northern Ireland. Notably, the aims of this project include both greater insight into this particular context for political violence and child development and also the provision of a template for study, both empirically and conceptually, of the impact of children’s exposure to violence in other regions of the world. Accordingly, in this paper, after a review of literature supporting this approach, we outline a social ecological model for the effects of political violence on children in Northern Ireland.

Next, we consider the application of this model to understanding relations between political violence and child development in Northern Ireland, including the development of methods to address gaps for testing the social ecological model. In this context, we also provide an overview of the ongoing study in Northern Ireland, and briefly review selected findings from the project to date. Finally, the applicability of this model and approach are examined for other contexts of community violence, including (a) another area in the world with histories of political violence, that is, Serbia and Croatia, and (b) a context of community violence in this country, that is, United States (US) inner cities.

Effects of Social Ecologies of Violence on Children

The scant research supports the promise of an ecological perspective for understanding child outcomes from political violence (Joshi & O’Donnell, 2003; Sagi-Schwartz, 2008; Shaw, 2003). Gibson (1989) emphasized the importance of considering contextual (e.g., experiences with political violence), inter-personal, and intra-personal (e.g., variations across individuals in coping abilities) factors in accounting for the impact of stress on children in situations of political violence. Among inter-personal factors, the family was identified as the most important and consistent positive mediator of stress. Supportive and harmonious family environments, parents’ display of concern for children, and parents’ serving as a secure base for children’s self-direction in everyday tasks may act as critical mediating processes. In a review of the limited available research, Elbedour, ten-Bensel, and Bastien (1993) reported evidence that children suffer from chronic and acute stress in war. Moreover, the impact on children of war was a dynamic interaction among multiple processes, consistent with an ecological framework, including the breakdown of community, the disruption of family, and the psychological characteristics of children. Punamaki (2001) reported that multiple factors were related to children’s positive developmental outcomes during a period of intense political violence in Chile. Positive mental health outcomes and social competencies in children were predicted by (a) a family atmosphere of low conflict and high cohesion, and (b) effective coping strategies (for example, positive view of the future). Finally, Bat-Zion and Levy-Shiff (1993) found that parents’ emotional manifestations and children’s emotional arousal were central factors mediating children’s stress responses to war-related experiences and stimuli.

At the same time, there are major gaps in the study of political violence, civil strife, and cultural contexts of terrorism and ethnic conflict as related to child development (Barber, 2004; Feerick & Prinz, 2003b). It remains that many studies proceed as if political violence occurs in a vacuum (Dawes & Cairns, 1998). There is now convincing documentation that war and political violence have many negative effects on the children, including heightened aggression and violence, revenge-seeking, insecure attachment, anxiety, depression, withdrawal, post-traumatic stress and somatic complaints, sleep disorders, fear and panic, poor school performance, and engagement in political violence (e.g., Sagi-Swartz, Seginer, & Addeen, 2008; Quota, Punamaki, & Sarraj, 2008). Accordingly, the goal now is to understand how and why, for whom and when, these contexts are associated with problems in children. This approach has promise for building advanced understanding and a foundation for how to intervene more effectively or prevent problems.

Process-oriented studies of the effects on children are rare, particularly investigation of the psychological factors related to the etiology, effects, and mechanisms of the impact of violence exposure on children. Moreover, approaches may appear ad hoc conceptually, that is, lack a guiding theoretical perspective or have limited cogency from an empirical perspective, including significant problems for interpretation in research design, measurement, and/or analytic approach. A next step is to mainstream the study of political violence and children (Cairns, 2001), that is, advance approaches consistent with state-of-the-art child development research. Standards of research design, methodology, approach to analysis, and theoretical development and testing need to be improved, including longitudinal model testing.

Children in ecological contexts of political violence may be exposed to multiple levels of violence simultaneously, and few studies have examined the many issues pertaining to exposure, including interrelationships between different types of exposure (Mabanglo, 2002). Definitions of and boundaries between political and community violence have been little examined (Trickett, Duran, & Horn, 2003). For example, one definition is the extent to which the child has been victimized by, or witness to, various forms of violence and violence-related activities in the particular community in which the family lives (Richters and Martinez, 1990). However, research seldom takes into account broader contexts of children’s exposure to conflict and violence, including cultural or political influences relevant to the impact of violence exposure on families and children.

We define sectarian community violence as political tension expressed at the community level. In other words, antisocial behavior, conflict and violence expressed between ethnic, religious, or cultural groups due to their confrontation on political, cultural or social issues. Thus, sectarian community violence reflects local levels of expression of conflict and violence due to political strife. Non-sectarian violence reflects “ordinary crime” that may be found in any community, regardless of political context, and is not specifically indicated between ethnic, religious or cultural groups.

Reflecting another level of analysis from a social ecological perspective, exposure to interparental conflict and violence is linked with problems in adjustment and well-being in children (Holden, Geffner, & Jouriles, 1998; Jouriles, Norwood, McDonald, & Peters, 2001). Processes underlying the development of behavior problems and perceptions of threat and diminished well-being in children have been tied to exposure to marital conflict and violence (El-Sheikh, Cummings, Kouros, Elmore-Staton, & Buckhalt, 2008; Grych, Fincham, Jouriles, & McDonald, 2000; Maughn & Cicchetti, 2002). Negative forms of marital conflict are related to interparental violence, and are likely to be co-morbid factors in predicting problems in the adjustment and well-being of children and families (Cummings, 1998).

Domestic violence does not occur in a social vacuum, and is affected by community or cultural contexts of violence (Martinez & Richters, 1993; Richters & Martinez, 1993a). Moreover, violence in the community and home may be interrelated in affecting children (Margolin & Gordis, 2000). Families with high levels of exposure to community violence are characterized by high conflict and a lack of cohesion (Cooley, Turner, & Beidel, 1995). At the same time, community and family violence are distinct influences on children’s maladaptive psychological functioning. Exposure to family violence is associated with child adjustment even when relations between community violence and child psychopathology are nonsignificant (Muller, Goebel-Fabbri, Diamond, & Dinklage, 2000). Community violence exposure exerts a negative influence on children’s psychological adjustment (Garbarino, Dubrow, Koselny, & Pardo, 1992; Lynch, 2003; Mabanglo, 2002), even when family violence is controlled (Linares et al., 2001).

Children’s exposure to community violence is linked with externalizing disorders, especially aggressiveness in males (Attar & Guerra, 1994; O’Keefe, 1997). Problems in emotional, cognitive and behavioral domains are also identified (Kuther, 1999; Singer, Anglin, Song, & Lunghofer, 1995), including depression (Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998). Community violence exposure is also linked with poor academic performance in urban elementary school children (Schwartz & Gorman, 2003). Some studies report males or older children are more often victims or witnesses of community violence (Jaycox et al., 2002; Richters & Martinez, 1993b).

With regard to psychological processes in children, disruptions in children’s capacities for self-regulation and control (Maughn & Cicchetti, 2002; Schwartz & Proctor, 2000), and social cognitive biases towards attributing more hostile intentions to others (Earls, 2003) have been associated with exposure to community violence. The impact of negative social attributions and biases in fostering children’s aggressive responding towards others has been shown (Crick & Dodge, 1994).

Other studies indicate poor parental monitoring, as well as exposure to community violence, contributed to children’s self-reported violent behavior in elementary and middle-school (Singer et al., 1999). In contexts of political violence parents may face particular challenges for monitoring the behavior and activities of children to avoid risk for adjustment problems, including involvement in antisocial behavior (Mazefsky & Farrell, 2005). Exposure to violence in communities and schools is dramatically higher for high-risk, urban youth (Berman, Kurtines, Silverman, & Serafini, 1996; Selner-O’Hagan, Kindlon, Buka, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1998). Child exposure to violence is related to psychological adjustment in African American children (Flowers, Lanclos, & Kelley, 2002) and mental health problems in immigrant (Latino, Korean, Russian, Armenian) children (Jaycox et al., 2002). Although little investigated, there are studies that suggest similar effects of community and family violence across ethnic groups (El-Sheikh et al., 2008; Schwab-Stone et al., 1995).

A Social-Ecological Model for the Impact of Political Violence on Children

Children’s exposure to conflict and violence may affect them at multiple and different levels of individual and societal functioning, with each level capturing a unique element of the effects of exposure on children. Thus, including each level will contribute to a more complete understanding than can be achieved by focusing on only one level of analysis. For example, various levels of analysis (e.g., economic, political, institutional, educational, individual) of the effects of communal conflict on children in Northern Ireland and other regions of the world involved in ethnic or communal conflict have been described (INCORE, 1995). In an influential conceptualization, Bronfenbrenner (1979, 1986) proposed an ecological-transactional framework for a more complete understanding of the effects of social environments on children (see also Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993; Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998). Ecological contexts consist of several nested levels of differing degrees of proximity to children’s functioning.

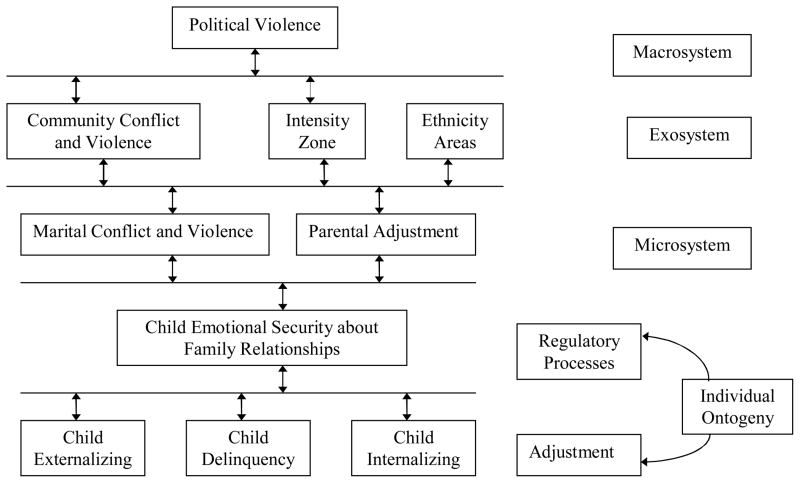

Based on this approach, Figure 1 also includes specific elements for variables in each level of the model for pathways surrounding political violence and child adjustment in Northern Ireland (Cairns, 1996; Lovell & Cummings, 2001). The factors, processes and pathways in the model to be tested are necessarily selective and limited to variables judged most pertinent to the present context, informed by past research and theory as described below, including studies of children and families in Northern Ireland (e.g., Cairns, 1987; Cairns & Mercer, 1984; Fay, Morrissey, Smyth, & Wong, 1999; Jarman and O’Halloran, 2000; Muldoon, 2004; Niens, Cairns, & Hewstone, 2003; Smyth and Scott, 2000).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework for Social Ecology of Political Violence in Northern Ireland. Adapted from Lovell and Cummings (2001).

Notably, in any social ecological model, some components or structural factors in neighborhoods or various other levels or systems may be relatively specific to the cultural context being investigated, whereas other or additional variables may be highly salient in other regions of the world with political violence. For example, the highly segregated characteristic of many neighborhoods (i.e., Catholic or Protestant) in Belfast is a defining structural factor of these neighborhoods (Shirlow & Murtagh, 2006). At the same time, racism may be a significant cause of conflict in other areas of the world with political violence, but is diminished as an issue in Northern Ireland by the fact that the overwhelming majority of residents are Caucasian.

Macrosystem

The macrosystem involves cultural beliefs and values, including societal, government functioning, and political discord and conflict at the level of interrelations between conflicting groups. Better relations at this level may not translate into better relations between groups at a community level. For example, a ceasefire agreed upon by political leaders may not stop violence or delinquency in a community. Relations between political processes and community behaviors may also vary widely from one community to the next. Thus, a ceasefire may result in a cessation of conflicts in low intensity regions, but could exacerbate conflicts in high intensity zones, if the conflicting groups perceived violence or delinquency as a means to subvert an unwanted cessation of hostilities (Darby, 2006). At the same time, a ceasefire may create needed space to enable conflicting groups to dialogue and respect their political and cultural differences (Nagda, 2006)

Exosystem

The exosystem reflects influences associated with the neighborhood and community. Measuring neighborhood and community as contexts for child development can be complex, since high and low risks areas may comprise the same community, and differences in perceptions of violence may vary substantially across different elements of the community (Guterman, Cameron, & Staller, 2000). A framework recognizing possible variability within neighborhoods is more promising than viewing communities as uniform influences from the children’s perspective (Coulton, Korbin, & Su, 1996, 1999).

Microsystem

The microsystem includes elements of the child’s environment with which the child interacts directly. Chief among microsystem influences is the family. Variations in marital and parent-child relations are prominent influences of family contexts on children (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000). Highlighting the significance of this level of analysis, Richters and Martinez (1993c) reported that adversities and pressures in the exosystem (community violence) increased risk for children’s adaptational failure by reducing the stability and safety of their homes (see also Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998). Relations between conflict in the family and community are increasingly reported (Halpern, 2001; Kaslow, 2001). Linares et al. (2001) found that community violence and family aggression each predicted behavior problems in children, with the effects of these experiences mediated by mothers’ psychological symptoms. Exposure to family violence may also moderate relations between exposure to community violence and adolescents’ adjustment problems (LeBlanc, Self-Brown, & Kelley, 2003). Family cohesion predicts resilience among children exposed to community violence (O’Donnell, Schwab-Stone, & Muyeed, 2002). Among parenting dimensions, reductions in parental monitoring increases vulnerability to community and family conflict and violence (Mazefsky & Farrell, 2005). In addition, parental adjustment has been identified as a pathway for the impact of political and community violence on children (Joshi & O’Donnell, 2003; Lynch, 2003; Shaw, 2003).

Ontogenic Development

The ontogenic level of analysis reflects the children’s processes of psychological functioning. Children’s emotional security (Davies, Harold, et al., 2002) and social cognitions and attributions about others (Cairns, 1987) are among the factors likely affected by political, community and family contexts (Lovell & Cummings, 2001). Individual differences in children’s characteristics may also account for some of the impact of exposure to violence, including age and gender, and also processes related to effects of conflict and violence at the level of psychological functioning, for example, emotional regulation abilities, social identity, effortful control, sensitization to conflict, and sympathetic and parasympathetic reactions to stress (Cummings & Davies, 2002; Maughn & Cicchetti, 2002).

At the same time, contextual factors, such as family histories, may influence individual differences in children’s responding to conflict and violence. For example, children may develop insecure avoidant regulatory patterns because they have been repeatedly rejected or treated negatively by parents in times of family stress and threat (Davies, Cummings, & Winter, 2004). Although these reactions may have been adaptive in historical contexts in the home by protecting children from punishing or hurtful treatment, these response patterns may also leave children more vulnerable to adjustment problems when faced with conflict and violence as they grow older or in other social contexts (Davies, Harold, et al., 2002).

The next wave of research on children exposed to violence needs to move beyond simply demonstrating correlations between exposure to violence and child adjustment problems to identifying the psychological processes that contribute to children’s adjustment outcomes. Emotional Security Theory (EST, Davies & Cummings, 1994) posits that children’s exposure to marital conflict and violence is linked with reduced emotional security about the marital relationship (Cummings, Schermerhorn, Davies, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2006). Security about parent-child attachment may also be reduced (Harold et al., 2004), with both forms of insecurity related to increased risk for children’s internalizing and externalizing problems. Emotional security is hypothesized to serve as a bridge, allowing children to feel safe to explore multiple social environments (Cummings et al., 2006).

Children’s regulatory processes are engaged in maintaining or regaining emotional security in multiple contexts (Cummings & Davies, 1996). Given that emotional security processes mediate relations between exposure to marital conflict and violence, emotional security may also factor in the effects of their exposure to community and political violence (Lovell & Cummings, 2001). Children exposed to high levels of community violence, either as witnesses or victims, may have less secure emotional relationships with caregivers (Lynch & Cicchetti, 2002). Social cognitive deficits are linked with aggressive behavior (Crick & Dodge, 1994) and moderate aggression in children from violent neighborhoods (Earls, 2003).

Surprisingly few age differences in responding are reported, with marital conflict and violence predicting internalizing and externalizing problems across the span of childhood (Cummings & Davies, 2002). Nonetheless, reviews of research in Northern Ireland support studying the effects of political violence in later childhood and adolescence, because of the incidence of violence, as perpetrator and victim, in this age period. Comparison of reactions to marital conflict and violence in boys and girls in the child development literature has yielded an inconsistent and weak pattern of findings (Davies & Lindsay, 2001).

Applying a Social Ecological Model to Children and the Troubles in Northern Ireland

A Brief History of the Troubles

The sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland is colloquially referred to as the “Troubles”. The conflict is underpinned by historical, religious, political, economic and psychological elements and arose from a struggle between those who wish to see Northern Ireland remain part of the United Kingdom (Protestants/Unionists/Loyalists) who make up about 50% of the population and those who wish to see the unification of the island of Ireland ((Catholics/Nationalists/Republicans who account for about 40%of the population) (Cairns & Darby, 1998). More than 3,500 people have been killed due to the political violence in Northern Ireland (NI) since the 1960s, a significant number given the relatively small population of Northern Ireland (Darby, 2001). There were seven attempts to reach political solutions between 1974 and 1994 (INCORE, 1995), with widespread support for a settlement by the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Nonetheless, violence, conflict, and political disturbances continue (First Report to the Independent Monitoring Commission, 2004). Although extreme forms of sectarian violence have declined (e.g., deadly violence), substantial incidences of multiple forms of sectarian violence and conflict continue to be reported (Summary of Statistics Relating to the Security Situation, 2006/ 2007). The boundaries between sectarian violence and ‘ordinary’ forms of violence – criminal damage, anti-social behavior – are blurred, so that sectarian violence may be underestimated by formal assessments (Jarman, 2005). For example, police may tend to underestimate rates of occurrence and specific ethnic groups (i.e., Catholics) may underreport sectarian acts, believing police are biased or will not respond.

Moreover, a decade has passed since the internationally welcomed 1998 Belfast peace agreement, and despite expectations of peace, political violence remains a daily occurrence especially among interfaced communities, that is, communities in which Catholics and Protestants live next to each other. Recent reports indicate an upsurge in anti-social behavior (McGrellis, 2005). Although political leaders have signed promising agreements, here as in other post-accord conflicts in the world, the conflict is not over (MacGinty, 2006). The ongoing analyses of political process in Northern Ireland indicates risks for continued and potentially escalating conflict and violence (Shirlow & Murtaugh, 2006). History suggests that it is difficult to predict future trends in sectarian violence in Northern Ireland. For example, prior to the late 1960s violence between Catholics and Protestants was low, even though many of the same potential impetuses to violence existed. The constitutional issues are not yet resolved (“Justice Moves”, 2007). If the ground or street level post-accord “peace” is lost, the loss of institutional levels of agreement would follow. If the peace process backslides, the younger generation, who have especially negative perspectives on the other group (Shirlow & Murtaugh, 2006), are likely to contribute to heightened hostilities (McEvoy, 2000). These matters highlight the importance of understanding these processes as they influence children.

A Social-Ecological Model for the Impact of the Troubles on Children in NI

Figure 1 outlines an ecological framework for the multiple levels of possible effects of political and communal conflict and violence on children in Northern Ireland (Lovell & Cummings, 2001). Elements at each level of analysis are examples, and the listing is not meant to be exhaustive. These levels of analysis of the effects of children’s exposure to conflict and violence are likely to be interrelated (Fay, Morrissey, Smyth, & Wong, 2001). Thus, it is important to recognize how the familial, psychological and community processes affect, and are affected by, the other levels of ecological functioning (Fay, Morrissey, & Smyth, 1999). An integrated, multi-disciplinary approach to understanding the effects of the Troubles on children is increasingly advocated by observers and scholars of Northern Ireland (Cairns & Hewstone, 2002; Niens, Cairns, & Hewstone, 2003; INCORE, 1995; Smyth, 1998).

Much mainstream child development research supports elements of the framework for relations between marital conflict and violence and child adjustment, including the mediating role of emotional security. However, little is known about the significance for understanding child development of the relations between broader contexts of political and community violence (macro - and exosystem levels) and family and individuals (micro and ontogenic levels) in Northern Ireland. More generally, little systematic study has been accomplished from an inclusive ecological perspective, including examination of the mediating role of psychological processes (Feerick & Prinz, 2003; Prinz & Feerick, 2003). On the other hand, among regions of the world with histories of ethnic conflict, investigations in Northern Ireland provide the strongest foundations for these next steps in research (see also Sagi-Schwartz, 2008).

The impact of the Troubles is not uniform, and varies in terms of relatively well-defined sub-regions of Belfast and Northern Ireland. For example, Smyth and Scott (2000) reported that children living in high intensity zones in Northern Ireland exhibited more anger, suspicion, and sometimes hatred towards the other community (Catholic or Protestant) than children living in low intensity zones. Families in high intensity areas have had more extreme experiences of a variety of forms of violence (including deaths and being caught up in riots), more often reported significant property damage (e.g., home destruction), had the highest incidence of painful memories and experiences of having to conceal things in order to feel safe, and had the highest report of multiple insecurities and fears, including reports that the Troubles had completely changed their lives (Smyth, & Wong, 2001). Residential segregation is a salient feature of urban life in Northern Ireland, thereby fostering in-group vs. out-group distinctions by children (Cairns, 1987). Jarman and O’Halloran (2000) examined interface zones between predominately Protestant and Catholic residential and commercial areas in Northern Ireland; much of the violence in the course of the Troubles has occurred in interface communities.

The psychological processes that may mediate or moderate the impact on children of ecological contexts of political violence merit particular consideration. Multiple factors are candidates as explanatory processes, including modeling, attachment related processes, patterns of emotional regulation, effortful control, sensitization processes resulting from repeated exposure to conflict, and also biological response systems reactive to stress, including sympathetic and parasympathetic reactions to stress (Cummings, 2004; Davies, Harold, et al., 2002; El-Sheikh et al., 2008). However, emotional security processes have been identified as especially promising in contexts of political processes. As noted above, recent studies have documented relations longitudinally between multiple family processes, regulatory processes of emotional security and child adjustment. Lovell and Cummings (2001) extended this notion to include community and political conflict and violence, hypothesizing that these ecological contexts also influenced children’s sense of emotional security, both directly due to exposure, and indirectly as a result of influences on family functioning, especially parenting and marital conflict and violence. Multiple aspects of children’s ecological settings of political and ethnic conflict and violence were posited to be related to children’s sense of security, with implications for both internalizing and externalizing disorders.

Thus, multiple aspects of children’s ecological settings of political and ethnic conflict and violence may be related to children’s sense of security about community, marital conflict, parent-child and family relationships, with implications for children’s adjustment problems. A reasonable extension of past research on family processes and emotional security is to hypothesize that if emotional security processes mediate relations between family functioning and child adjustment, emotional security about family and community are likely to mediate relationships between exposure to community and political violence and children’s adjustment (Lovell & Cummings, 2001).

Another main psychological process affected by the political violence is children’s social identity, which has implications for children’s social cognitions, attributions and behaviors towards other groups. Children’s awareness of these distinct categories in Northern Ireland has long been documented, with such awareness developing by at least five years of age (Cairns, 1987). The fact that about 90% of children in Northern Ireland attend segregated schools further alerts them about the distinct separation on a daily basis. Cairns and Mercer (1984) reported evidence that Northern Ireland’s youth possess an emotional attachment to their respective social categories, and they may show heightened hostility towards other adolescents when adolescents are under threat or stress (Trew, 1981). Past work in Northern Ireland argues for the cogency of these processes as explanatory variables for the effects of the Troubles on children in Northern Ireland (e.g., Fay, Morrissey, Smyth, & Wong, 1999; Jarman and O’Halloran, 2000; McEvoy, 2000; Muldoon, 2004; Niens, Cairns, & Hewstone, 2003; Smyth and Scott, 2000).

An Investigation of Children and Political Violence in Northern Ireland

Our ongoing study investigates a social ecological framework for the effects of political violence on children and adolescents in working class Catholic and Protestant areas of Belfast, Northern Ireland. In the model guiding this research, emphasis is placed on systematically examining ecological and psychological processes regarding political violence in Northern Ireland as a context for children’s exposure to ecologies of violence. The theoretical model emphasizes understanding the effects of political conflict and violence on children’s experiences in the community and family, and their own processes of regulatory functioning, adjustment and development. Moreover, psychological processes related to children’s development are examined for their possible mediating or moderating roles in accounting for the impact of ecologies of political violence on children. Thus, this study aims to further deepen process-oriented understanding of the effects of political violence on children, including the effects of cultural and ethnic violence and conflict on family, community, and child well-being, with possible implications for other regions of the world with sectarian or other forms of ethnic conflict and violence.

Developing and Adapting Instruments for the Context of Northern Ireland

Filling Gaps in Measurement to Test the Social Ecological Model

A particular challenge to this research was the development of an assessment battery appropriate to testing our social ecological model in Northern Ireland. The challenge was not just that the needed assessments did not yet exist, but also that we had needed to develop measures appropriate to the context provided by the culture of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Moreover, the optimal way to obtain the necessary data from both mothers and children was by means of a survey company conducting interviews of mothers and children in their homes. Thus, another requirement was that these measures had to be suitable to this format, including the time limitations of conducting surveys door-to-door.

For example, one of our key explanatory constructs was emotional security, based on the notion that the impact of conflict and violence on children at multiple levels of the social ecology would be mediated by the impact on children’s sense of emotional security. However, although well-established questionnaires existed for the effects of marital conflict and violence on children’s emotional security, no instruments existed for children’s emotional security about community, a potentially important mediating process according to our conceptual model for understanding the effects of community violence on children.

Moreover, we posited in our model that in the contexts of political violence and children, sectarian community violence, that is, politically-motivated antisocial behavior at the community level, would be ecologically and conceptually distinct from “ordinary” community violence. Relatedly, we posited that pathways of effects on children due to politically-motivated community violence were potentially distinct from the impact of other forms of community violence. Thus, our goal was to differentiate between the effects of sectarian and non-sectarian community violence on family and adolescent adjustment.

However, no efforts had been made in the past to develop approaches to measurement of community violence that made these discriminations. Similarly, matters related to emotional security about the community and sectarian community antisocial behavior were expected to be context-specific, that is, peculiar to expressions of community violence in Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods in Belfast. Thus, even if the measures had existed, it was highly questionable whether assessments developed for other social, cultural or political contexts would be suitable for neighborhoods in Belfast, since any measures developed elsewhere would be suspect in terms of ecological validity in Northern Ireland.

We also wished to measure ongoing levels of political violence at a country-wide level, in order to be able to assess how changes in the political status of the conflict over time influenced community and family relations, and child development. Conceptually, this was also a new direction. Thus, again, new approaches needed to be devised to make these assessments at the level of the macro-system. After much discussion and debate, we decided that analysis of newspaper accounts of the Troubles over time would provide a record most sensitive to any changes that may be occurring over time. Notably, this level of analysis, because it reflected country-wide changes, holds promise for pay-off only after a long period of assessment, based on multiple waves of data collection. Thus, substantive results were not likely to emerge based on the first wave of data collection, or even the first couple of waves.

The first year of our project, which we call the pilot year, was designed to allow us to develop these measures and collect preliminary data to establish their psychometric reliability and ecologically validity. Notably, we propose that a similar pilot phase towards the adaptation or development of measures appropriate to study in new socio-ecological contexts is likely to be an essential requirement for studies of sectarian, ethnic and/or political violence and children in any new context or culture. The pilot phase thus addressed critical gaps for assessing the social ecological model, including the development of measures of (a) sectarian and (b) non-sectarian community conflict and violence, (c) children’s emotional security about the community, and (d) political tension at the macro-level. The pilot year was also used to refine the measurement battery as a whole, including any modifications needed in wording and description to be appropriate to the social and linguistic context.

Focus Groups in Belfast

Forms of expression of sectarian community violence may be specific to particular areas of sectarian conflict. Sensitive to this possibility, a first step was to conduct focus groups held in multiple working class neighborhoods in Belfast.. The focus groups explored issues relating to both inter- and intra-community relations including: perceptions of what constitutes a community, attachment to community and place, the extent of own/other community violence and perceptions of the predominance of one type of violence opposed to the other (Campbell et al., 2008). This research was predicated upon the study of four segregated working class communities in Belfast, including high and low violence interface areas comprised of Catholic and Protestant communities, respectively. Determinations of high and low violence were based on information supplied by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. In each community access to participants was gained through community groups and organizations. The age of the participants ranged from 21 to 55 years and each group was comprised exclusively of female participants with children. All focus groups were audio taped and transcribed. Each member of the research team examined the transcripts and independently identified items to be included in the two scales. Team members came together to discuss the items and refine the two measures.

A Brief, Longitudinal Study in Londonderry/Derry

A brief, two-wave study was next accomplished in Londonderry/Derry, Northern Ireland, to provide an initial test of hypotheses and further establish the new measures (see Goeke-Morey et al., 2008). One hundred and four mothers from working class neighborhoods completed the new measures and other measures used for construct and predictive validity tests. Children’s perspectives were not assessed in the pilot study. Following extensive discussions by the entire team in Belfast on these and other matters related to assessment, a second wave of testing of the Londonderry/Derry families participating in this first study was conducted, including changes made in some cases to further refine measures. Further psychometric assessments and conceptual refinements based on email and weekly conference calls resulted in the instrument battery being finalized and suitable for use in the first wave of testing.

The Sectarian Antisocial Behavior (SAB) and the Non-Sectarian Antisocial Behavior (NAB) scales resulted, including both mother- and child-report batteries. The SAB is a 12-item scale assessing children’s exposure in the previous three months to a range of sectarian-motivated behavior such as seeing stones or objects thrown over peace walls, seeing houses or churches paint bombed, or seeing someone killed or seriously injured by a member of the other community. The NAB is a 7-item scale assessing children’s exposure to nonsectarian behavior such as drugs being used or sold, robberies, or individuals killed or injured unrelated to sectarian affiliations. Exploratory factor analysis clearly distinguished sectarian and nonsectarian items. The study in Londonderry/Derry confirmed that children are currently exposed to relatively high levels of community antisocial behavior and violence in Londonderry/Derry, with mothers reporting that 100% of children were exposed to at least one sectarian act weekly, and 38% of the sample was exposed to at least one non-sectarian behavior weekly. Both SAB and NAB exposure were related to increased child emotional, conduct, hyperactivity, and total problems, and reduced prosocial behavior. A limitation is that relations could by inflated by mothers’ reporting bias. Exposure to sectarian conflict was a stronger predictor of child problems than exposure to non-sectarian conflict. Moreover, Cronbach’s alphas for the SAB in wave 1 of the Belfast study (see below) were .94 (mother-report) and .90 (child-report), and for the NAB were .78 (mother report) and .74 (child report).

Extending the conceptualization of security beyond the family system, a Security in the Community Scale (SIC) also resulted, informed by the focus groups and refined during the two-wave study in Londonderry/Derry (alpha .85). Notably, the factor structure, internal consistency, inter-correlations, convergent and discriminant validity, and criterion validity of the new instruments were each supported. Supporting validity, in analyses of the Londonderry/Derry data and the wave 1 Belfast data (see below), children’s exposure to community violence predicted insecurity on the SIC, and SIC scores significantly predicted child adjustment problems. SIC scores (reflecting insecurity) were higher for children living in the high violence areas than in low violence areas, with analyses of violence histories (e.g., the number of politically motivated deaths) based on public records on violence histories compiled by a demographer expert in ethnic neighborhoods in Belfast.

The development of the Newspaper Assessments of Political Conflict and Violence is ongoing. The goal is to examine how macro-level political tension changes over time and to test whether such changes affect community, family and individual factors. Newspaper articles are randomly chosen from relevant issues of The Belfast Telegraph and the Irish News, two widely read newspapers in Northern Ireland. Relevant articles are coded by culturally informed individuals living in Northern Ireland for the intensity of political tension between Catholics and Protestants. Reliability of the article identification procedure developed was assessed by independently identifying relevant articles from the same sample of dates and assessing inter-rater reliability using Cronbach’s alpha (α = .80). From the pool of all articles identified as relevant, a select number from each of the two papers will be randomly chosen for content coding. Three coders rated whether each article reflected mostly positive (1) or mostly negative (0) relations between Catholics and Protestants. Given that articles could contain indicators of positive relations and negative tension, coders also rated separately on 5 point scales the degree to which the article reflects negative tension and positive relations, respectively. For each construct, a composite of the three coders’ ratings of each article will be calculated. This non-manualized form of coding is recommended in situations in which experience within a particular environment informs the understanding of the construct (Waldinger, Schulz, Hauser, Allen, & Crowell, 2004).

A Longitudinal Study of Mothers and Children in Belfast

Participants

In the initial wave of Phase 1, 700 mother-child dyads (N=1400) from 18 working class areas in Belfast participated. Children were preadolescents or adolescents (M=12.1 years, SD=1.8), including boys (n=339) and girls (n=361). Based on stratified random sampling of ethnicity and history of violence, families were selected with at least one child in the household between 8 and 15 years of age. This age range was chosen based on several factors: (a) the official census only tracks the presence of children under 16 in households, (b) by 8 years of age, children are aware of the social distinctions being investigated, and (c) children 10 and over are most likely to be participants, or victims, in the Troubles. Both single-parent (n=396) and two-parent families (n=304) are included, representing the nature of working class families in Belfast, and providing an opportunity to examine the moderating role of family structure on relations with children’s adjustment.

For pragmatic reasons, mothers, rather than fathers, were selected as the parent reporter: (a) many families in working class Belfast are led by single mothers; (b) mothers are more likely than fathers to be available for in-home surveys during the day; and (c) including many mothers, and only a small number of fathers, as parental reporters could pose significant problems for analysis regarding comparisons among families. The Northern Irish population is overwhelmingly white. At the same time, there are well-defined differences in ethnic groups, reflected in oftentimes highly segregated (by ethnicity) living arrangements and schooling. Sampling of ethnic groups (40% Catholic, 60% Protestant), was representative of the population distribution in the region (43% Catholic and 57% Protestant; Darby, 2001).

The 18 areas specifically selected by the team were informed by analyses of representative neighborhoods and family structures by Peter Shirlow, a demographer expert in ethnic neighborhoods in Belfast. The areas, both Protestant and Catholic, respectively, provided representation of a range of historical differences in sectarian violence intensities. By sampling areas ranging relatively widely in experiences of violence associated with the Troubles, the sample adequately represented differences across neighborhoods in children’s exposure to violence associated with the ethnic conflict in working class Belfast. Notably, potential confounds for the socio-economic status (SES) of families are controlled by focusing data collection on working class areas highly similar in SES, which are also historically most associated with conflict and violence related to the Troubles. The data used by Shirlow in these determinations regarding violence histories were supplied by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, which also provided the opportunity to measure social deprivation at the community (enumeration district, ED) level. Ethnicity estimates (Catholic; Protestant) are based on the 2001 Census of the population of Northern Ireland. Conflict levels are based on the number of sectarian incidents from 1996 to 2003. Although police are disproportionately Unionist/Protestant in terms of numbers, concerns about possible bias have diminished in recent years due to a positive discrimination policy which has recruited more Catholics (Osborne, 2004). Moreover, this identification is based on multiple sources, that is, based on police records from the Police Service for Northern Ireland (PSNI) supplemented by records kept by local community based organizations (e.g., the Pat Finucane Centre), and material from local newspapers (e.g., the Belfast Telegraph, North Belfast News, Anderstown News, Ulster Star).

Notably, families in working class Belfast are highly geographically stable, with families often living in these areas for generations (Shirlow & Murtaugh, 2006). Even after school graduation, children often continue to live and work in these areas. In our sample, at the start of the study 97% of mothers had lived in Northern Ireland virtually all their lives. Mothers had lived in their current ward an average of 21 years, with 73% living in their present area 10 years or longer.

Procedure

Data is collected via in-home interviews lasting 1–2 hours conducted by Market Research Northern Ireland (MRNI), an established survey company based in Northern Ireland with considerable experience completing survey work in the community (http://www.mrni.co.uk/). Home interviewing is the method of choice in Northern Ireland where telephone coverage is incomplete and travel to laboratory locations is difficult. Notably, interviewers employed by MRNI are drawn from local communities and therefore likely to build excellent rapport with these families. Notably, all 700 families from wave 1 agreed to be contacted again for wave 2. Thus, there are substantial bases for expecting the survey company to be successful in continuing to work with these families across multiple waves.

Measures

The core of the battery will remain the same each year to permit longitudinal analyses assessing changes in adolescents’ adjustment linked with ethnic conflict and community violence. As children develop into older adolescents or emerging adults in later phases of the study, new instruments will be added to more intensively assess mental health and adjustment outcomes and developmental issues in adolescents or emerging adulthood.

Emphasis was given to constructs likely to be particularly salient for working class youth in this high conflict area, focusing on behavior problems and civic engagement. To enhance validity of the measures, when possible, we chose instruments created or commonly used in Northern Ireland, and batteries were reviewed by Northern Ireland colleagues and MRNI, with adjustments made to ensure culturally sensitive language. All measures used in Phase 1 demonstrated adequate or excellent internal consistency. Mindful of the need to keep the battery lean for effective use door-to-door, we carefully selected instruments that assess primary constructs of interest without being overly burdensome for mothers and adolescents.

Testing the Social Ecological Model: Process-Oriented Directions

In the space below, we provide brief summaries of analyses around selected topics to illustrate findings from this approach. Theoretically-based model tests are rare in the study of political and community violence and child development. Process-oriented empirical studies are important next steps in research, essential to identifying the psychological bases for the impact of these forms of violence on children, and are ultimately needed for informed intervention or prevention for children and families in these areas.

Testing the Social Ecological Model: Pathways Through Marital Conflict, Parental Monitoring, and Emotional Security

Cummings, Merrilees, Schermerhorn, Goeke-Morey, Shirlow, and Cairns (2008) extended Emotional Security Theory to include multiple sources of emotional security, including emotional security about marital conflict and the community. The particular focus was the role of marital conflict and children’s emotional security in their adjustment in the context of politically-motivated community antisocial behavior. An extensive literature has shown that marital conflict affects children’s emotional security and adjustment (Cummings & Davies, 2002). However, many questions remain about whether community violence affects marital conflict, and whether pathways through marital conflict and other family processes (e.g., parenting, Davies & Cummings, 2006) account for child outcomes, including the role of sectarian and nonsectarian community violence in contexts of political violence.

Testing predictions of the social ecological model by means of structural equation modeling, an objective measure of histories of political violence (i.e., public records of politically motivated deaths) was related to elevations in both SAB and NAB. Distinctive pathways were identified for SAB in comparison to NAB. SAB was directly related to children’s increased emotional insecurity in the community, and also greater marital conflict. Marital conflict, in turn, was associated with greater insecurity in the interparental relationship. Internalizing problems were most proximally associated with children’s emotional insecurity, with regard to the community and the marital relationship. Marital conflict was also associated with less effective parental monitoring, with both marital conflict and parental monitoring associated with children’s externalizing problems. By comparison, fewer pathways were identified for NAB, with no pathways relating to emotional insecurity in the community, marital conflict, or problems in parental monitoring. Thus, unique links between sectarian antisocial behavior and marital conflict and parental monitoring in the family were found, with pathways also identified from emotional security about the marital relationship and community to child adjustment.

Thus, as hypothesized in the theoretical model, support was found for multiple family systems (marital conflict and parental monitoring) as proximal mediators of pathways of the effects of sectarian community violence on child adjustment. With regard to political violence and children, histories of political violence were linked with elevated levels of sectarian and nonsectarian community violence. A new finding was that SAB was more predictive of family functioning and children’s psychological processes of emotional insecurity than NAB. The findings are consistent with past reports of relations between marital conflict and parenting in affecting child adjustment (Cummings & Davies, 2002) and relations between marital conflict, emotional security about marital conflict and child adjustment (Cummings et al., 2006), with a new finding that emotional insecurity about community also related to child adjustment.

Future research will explore bidirectional relations between the social ecological model and child adjustment. Recent longitudinal work on bidirectional relations between marital conflict and children’s responding indicates that children and marital conflict are mutually influential (Schermerhorn, Cummings, Davies, & DeCarlo, 2007). For example, children’s dysregulated behavior during marital conflict (e.g., misbehavior, aggression) is linked with increased marital conflict over time. However, study of bidirectional relations between community and family conflict, on the one hand, and child adjustment, on the other, await the next waves of data collection, which will provide needed longitudinal data for these tests.

Testing the Social Ecological Model: Pathways Through Family Conflict, Cohesion and Emotional Security

Community violence also has implications for single parent families. Few studies have made comparisons of process-models as a function of family structure, or investigated relations between community violence and family conflict for multiple family structures. Single parent families are neglected in studies of interadult or family-wide conflict and child adjustment. Moreover, single parent families are more prevalent in areas of high sectarian conflict, making the inclusion of these families especially pertinent to the study of political violence and child development. Testing the generalizability of the social ecological model to all family forms is an important goal, so that all families may potentially benefit from information that may inform later intervention or prevention programs.

Path analysis was conducted to examine links between various levels of the social- ecological model (Cummings, Schermerhorn, Merrilees, Goeke-Morey, and Cairns, 2008). Specifically, sectarian antisocial behavior predicted higher levels of family conflict and insecurity about the community, and predicted lower levels of family security, security in the parent-child relationship, and prosocial behavior. Family and child emotional security processes thus played mediating roles via multiple pathways. Family conflict was related to higher levels of total problems and lower levels of prosocial behavior. Family cohesion, acting as a positive influence on child adjustment, was associated with higher levels of security in the parent-child relationship, security in the family, and prosocial behavior, and lower levels of total problems. Security in the parent-child relationship and security in the family both related to higher levels of prosocial behavior, and insecurity in the community was linked with total problems and (unexpectedly) prosocial behavior. This last finding may indicate that in contexts of political violence children are more prone to aggression against outsiders and prosocial behavior in their own communities (Sabatier, 2008). The pathways were generally similar for single- vs. two-parent families.

In summary, these initial tests of Emotional Security Theory in the context of a social ecological model provided promising support for notion that community violence affects child outcomes through family and child processes, and multiple forms of emotional security, in the context of political violence and children in Northern Ireland.

Testing Social Identity as an Explanatory Process

Another direction in a process-oriented account is to test social identity as a factor in the impact of the Troubles. In this regard, another theoretically-driven analysis is investigating the long term consequences of political violence by examining the relationship between mother’s childhood exposure to political violence and her current mental health (Cairns, Merrilees, et al., 2008). In addition we explore the transgenerational nature of this relationship by investigating the impact of mother’s childhood exposure to political violence on the current mental status of her child. All of this is done using Haslam and Reicher’s (2006) social identity model of stress which uses social identity as a framework for understanding the basis of different coping responses to stress - an idea which is particularly apt in the context of a social identity based conflict such as that in Northern Ireland (Cairns, 1982). Social identity has also been identified as a significant factor in the impact of the Croat/Serb conflict (Ajdukovic & Biruski, 2008). The results from model tests suggest that mother’s social identity is a significant moderator in the link between her experience of the troubles and her current mental health, even controlling for levels of religiosity. However, different patterns of results were found for Catholics and Protestants. For Catholics, having a high social identity acted as a buffer such that the link between experience with the troubles and current mental health was weaker for mothers with high social identity. For Protestants, high social identity appeared to be a negative factor strengthening the link between experience of the troubles and mothers’ mental health. Links were also found between mothers’ mental health symptoms and children’s current mental health symptoms, that is, mothers’ adjustment mediated child adjustment for Catholics and Protestants. Thus, the results support the notion that social identity is an important factor in understanding stress processes for families in the context of political conflict in Northern Ireland.

Religiosity as an Influence

Religion is meaningful to mothers in this socially and economically deprived area of Belfast, with two thirds reporting their religion is important to them, and that they attend religious services. The question arises, in the context of the segregation and conflict between the Catholic and Protestant communities, does religiosity influence child and family functioning for the better or the worse? Moreover, is mothers’ religiosity a buffer for children, or rather does it exacerbate the negative effects of family conflict and parental maladjustment so common in low SES areas such as this?

Preliminary analyses indicated that even in the context of deprivation and sectarianism, religiosity was associated with positive adjustment. Maternal religiosity, particularly church attendance, predicted more adaptive family functioning. In addition, mothers’ evaluation of the importance of religion and her Christian attitudes, in addition to church attendance, predicted fewer adjustment problems and more prosocial behavior in children, as well as stronger and warmer relations between mothers and children and greater general security in the family.

Furthermore, mothers’ religiosity moderated relations between family and child functioning. For example, mother’s religiosity buffered children from harmful effects of her adjustment problems on children’s emotional security. That is, when mothers had a strong faith and Christian attitudes, even if she was less psychologically healthy children felt more secure about their relationship with her and more secure about their family. However, the role of mothers’ religion in this social and political context was nuanced. Mothers’ religiosity intensified positive relations, such as mothers’ control promoting child prosocial behavior and family security to a greater degree when mothers were more religious, but it did not magically make all bad things good. In some cases, mothers’ religiosity magnified the negativity of family and parent problems. For example, mothers’ religiosity intensified the influence of her partner’s drinking on children’s adjustment problems, mother-child security, and children’s prosocial behavior (Goeke-Morey, Cairns, et al., 2008).

Extending the Social Ecological Model to Other Regions

From the beginning we have been interested in Northern Ireland as a starting point for the study of political, ethnic and social conflict and child development, including regions beyond Northern Ireland. The first step was developing the model and testing it in a pertinent context, such as the well-documented and important political conflict in Northern Ireland. Now that this research is underway, and the approach appears promising, we are considering the applicability to other regions. The regions we consider for the sake of this review as examples are Serbia and US inner-cities. However, before turning to these specific contexts, we will consider some of the principles, issues and concerns that arise from our work in Northern Ireland as relevant to generalizing the approach to other areas.

General Considerations

The History of the Sectarian Conflict

In order to apply a theoretical framework to another region of the world, one must have substantial knowledge of the history of the area. For example, many people know there was intense conflict and violence in Northern Ireland for several decades beginning in the late 1960s. However, knowing the long-standing nature of the conflict in Northern Ireland, including key figures in the conflict, advances the relevance of the past as context for the current-day conflict in the region. For those members of the team from other areas spending time in the region interviewing people, learning more about the relationships among individuals on different sides of the conflict, and simply observing the physical environment were important for developing a fuller understanding of the current conflict, including the relevance of the conflict history. For example, seeing the modern-day mural depicting King William of Orange at the 1690 Battle of the Boyne, which included the defeat of the Roman Catholic King James and is credited with the liberation of the Protestants, highlights the importance of historical events for the current conflict, and the salience for Catholics or Protestants of seeing such murals on a daily basis. As another example, observing first-hand an intense “parade” in Northern Ireland during the marching season provides another valuable perspective on these events, including how history is kept “alive” by marchers beating angrily and loudly on their drums.

It is also relevant to consider “when” a study is occurring in the course of the history of the conflict: pre-conflict tension, height of hostilities, midst of transition, post accord. This matter is also relevant for the evaluation of safety and practical issues of access to participants and ability to conduct the research. The point of entry into the chronology of a conflict is relevant to issues such as the possible scope of the project and the variables to be included. In the height of a conflict and its aftermath in war torn regions, children and families are dealing with many additional issues, including being physically safe (e.g., from kidnapping, murder), loss of parents or children, having enough food to eat, clean water, and medical care, availability of school and homes, electricity, freedom of movement, as well as significant psychological distress. The research design should include measurement appropriate for the region and point of entry into the chronology of a conflict.

A Culturally Informed Approach

Cultural matters are likely to heavily influence the specifics of any application of the general social ecological model. For example, there may also be cultural differences in perspectives on violence and aggression toward other groups, including proneness to engage in physical and verbal altercations with others and differences in attitudes and beliefs regarding the acceptability of engaging in violence against others, with implications for children’s involvement in violence. Cultural views may contribute to differences in particular social ecologies in terms of (a) norms for family relationships, including respect for elderly family members and extended family relationships, with the potential for secure relationships with additional family members beyond the nuclear family; (b) norms for marital relationships, including the degree to which marital violence is acceptable; and (c) the treatment of children, with implications for child abuse. Cultural views may also affect perceptions of war, terrorism or political conflict. For example, according to Barber (2008), Bosnian youth viewed the war as senseless, incomprehensible and a source of feelings of threat whereas Palestinian youth viewed the political conflict as insulting and intrusive, and an impetus to become involved in political violence.

Cultural contexts may act at the individual or family levels, with implications for the effects of violence. For example, differences between families in socioeconomic status may alter exposure to violence, as well as resources for responding to, and coping with, violent acts. Cultural, family, and individual child differences in views on religion may have implications for the impact of violence, with some youth and/or parents using religion as a strategy to cope with exposure to violence and losses resulting from the violence. Focus groups or other qualitative approaches are another useful avenue for further developing an understanding of the culture of a region from the perspective of groups or samples that are of particular interest.

Identifying cultural differences can contribute to research directions in other ways. Cultural norms about social desirability or authority, gender, social acceptability of discussing issues, taboos, or other matters may impact the way in which participants answer questions, or even their agreement to participate in the research in the first place. In some cultures, for example, multiple contacts may be needed before participants are comfortable being completely forthcoming with their responses. In some cases, other means of data collection such as observation or archival records may be necessarily to supplement the self report. These issues may influence the point of entry with participants. For example, in some cultures, it may be more appropriate to talk with the men in the community, or gain permission through the husband to talk with the wife. Researchers must be particularly attentive to ways to ensure a representative sample and valid responses. In our case in Northern Ireland, we engaged participants through a professional survey company that relied on predominantly middle aged, female interviewers native to the region to conduct interviews. Moreover, we edited the battery in consultation with those native to the area who told us that certain questions (corporal punishment, domestic violence) would be off-putting and could compromise the interview.

Research Team Representing the Region and Pertinent Aspects of the Discipline

When approaching research in a different region, there is value in members of the research team undergoing a process of introspection to avoid ethnocentrism, that is, fitting matters into the preconceived notions of our own culture or way of thinking. Ethnocentrism can color the questions asked, the way the research is conducted, and the way findings are interpreted and reported. Another imperative is to collaborate with colleagues from the country of interest (Cairns, 1996). Any research effort will be severely hindered without team members from within the culture, including team members who are highly knowledgeable about culture in those areas. In our case, we are fortunate that our research team included faculty who have lived in Northern Ireland for most of their lives, and thus knew a great deal about Northern Irish culture. Frequent contact and effective communication essential between members of the research team at different sites is essential, including in-person, video, phone, and email contacts. A research team with diverse and varied strengths from a scientific perspective contributes to obtaining a fuller picture of context, and adequately developing research design and conceptualizations to meet the standards of cutting-edge developmental research.

The Specific Types of Violent Acts

It is also important to know the specific types of violent acts that occur in that area, including the context in terms of the chronology of the Troubles. When we began our work in Northern Ireland, several excellent measures of children’s exposure to violence had been developed for other regions, but none were specifically designed for use in violent areas in the NI. From the outset, it was clear that there were differences between the types of violent acts that occur in other areas, such as US inner cities, compared with those acts occurring in high conflict areas in Northern Ireland. Qualitative research methods are particularly well suited to gaining insights regarding this sort of contextual information, as well as information about the wording about elements of the social ecological context that is in common use. For example, the focus groups we conducted were valuable in helping identify provocative forms of sectarian antisocial behaviors confronting children, such as witnessing the use of petrol bombs and seeing stones thrown over peace walls. Based solely on US research on community violence, we would have had little basis for including such items in the questionnaires we developed for this project.

The Context of the Conflict

Differences in the context of the conflict may also have important implications for understanding the impact of exposure to violence and conflict. For example, there may be important differences in meaning and effects of violence and antisocial behavior on children and families, depending on whether the violence occurs in the context of war; battles between paramilitary organizations; or fighting between individual members of society.

Another contextual factor is whether war has caused people to leave their homes. This context of war and ethnic conflict, resulting in many people becoming refugees, has significance for sectarian conflicts in many parts of the world. The reason for the conflict should be evaluated, such as disputes over land, religion, or political issues such as a desire to be an independent state. Another distinction is whether conflicts occur primarily between political figures compared to conflicts fundamentally originating at the grassroots level. The role of children in the violence may vary from one region to another.

Legal Matters in the Region and Reliability of Archival Sources

Another consideration is the degree to which police enforce the law or show favoritism for one side or the other, or the degree to which the community supports the legal system and the police. Areas may vary greatly with respect to these considerations, including relations between ethnic groups, police, and outside political forces. In Northern Ireland, for example, in the history of the Troubles police could come under physical attack when responding to emergency calls for assistance, historically most often in Catholic neighborhoods.

Reliance on the police may vary across groups, including whether one group regards the police as allies while another has more negative perceptions of them, with implications for the feasibility and interpretability of some types of archival data, such as police records. Other sources of archival data (e.g., newspapers) may be problematic due to potential biases. It may be important to triangulate reports from various sources, including multiple possible “sides” about the conflict, for example, “Catholic” or “Protestant” newspapers, census, governmental records, or crime records. These records can also be useful in ensuring representative sampling, or tracking intensity of conflict.

Developing or Adapting Instruments

As in our research on political violence and children in Northern Ireland, it may be the case that instruments are not currently available to test all the constructs in a theoretical model, or that measures need to be greatly adapted to suit the context provided by a region. Other challenges are translation and adaptation of established measurements when the instruments are not psychometrically validated. Researchers are encouraged to create and validate instruments, or use instruments that have been adapted for the target population and pilot tested to determine the cultural validity (Sue & Chen, 2003). When translating measures to another culture, researchers should attend to the semantic, content, technical, criterion and conceptual equivalence of the instruments (Bravo, 2003). Even when working in English speaking parts of the world, the instruments validated in the US may need to be adapted to be equivalent and valid.

This approach serves as a template for how researchers in communities in other regions can advance adequate, ecologically sound assessments of constructs. Culturally-distinct forms of sectarian antisocial behavior may vary widely across societal contexts. The generalizability of assessments developed in one culture may have limited generalizability to other cultures. Accordingly, it is essential to consider whether it is necessary to develop culturally-appropriate measures or make significant adaptations on existing measures so that they are appropriate.

Applying the Conceptual Model to Other Parts of the World: Serbia and Croatia

The History of the Sectarian Conflict

The social ecological model that developed for Northern Ireland has relevance in other areas of the world. The emphasis is on including multiple levels of the social ecology in areas of political violence in order to advance more sophisticated assessments of the pathways through which war, terrorism and political violence affect the children (Figure 1). To provide an example of some of the issues in generalizing the model, we briefly consider the case of Serbia and Croatia. This focus is not on a review of the political conflict but how to approach studying conflict from the perspective of the children.