Abstract

The synthesis of new trimethoxybenzylidene–indolinones is reported. Their cytotoxic activity was evaluated according to Developmental Therapeutics Program, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, drug screen protocols. The study of the mechanism of action suggests that inhibition of Nox4 in B1647 cells (acute myeloid leukemia) could contribute to the antiproliferative effect of some compounds. Moreover, inhibition of tubulin assembly was observed for the most cytotoxic compound, and the structural basis for this activity was delineated by binding models.

Keywords: Oxindole, Knoevenagel reaction, Antiproliferative activity, NADPH oxidase 4, Tubulin assembly

1. Introduction

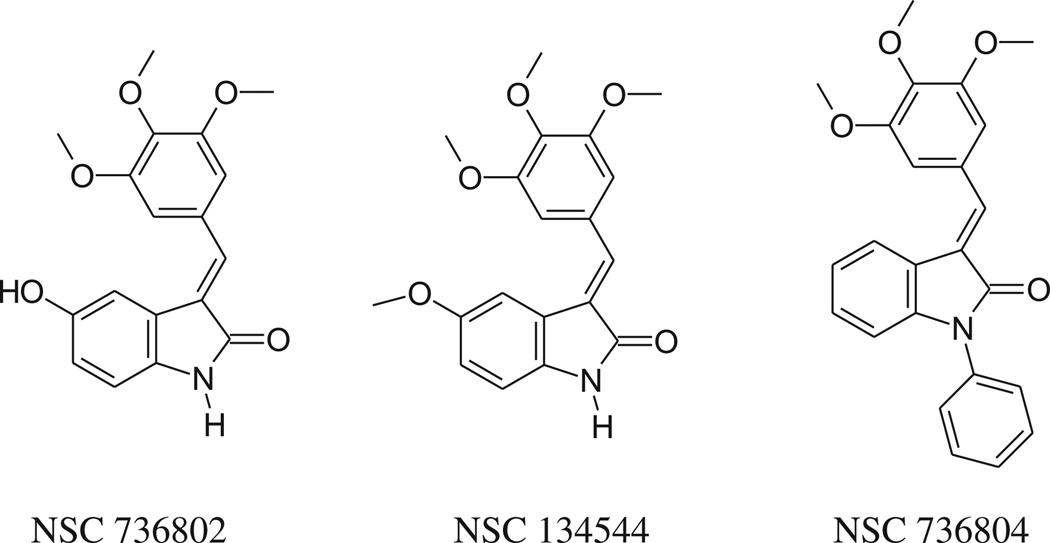

The 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl group is present, free or hindered, in well known antitumor agents, such as combretastatin A-4 (CSA4), colchicine and podophyllotoxin. With this in mind, we started to study the antiproliferative activity of Knoevenagel adducts in which the oxindole moiety is linked to a 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl group by means of a methine bridge, and in 2006 we published a paper describing an initial group of compounds [1]. Three derivatives (Chart 1) showed interesting activity profiles, encouraging us to develop new analogs (3–15, 18, 19, see Scheme 1) in which the variations concerned primarily the indolinone moiety.

Chart 1.

Most active derivatives described in Ref. [1].

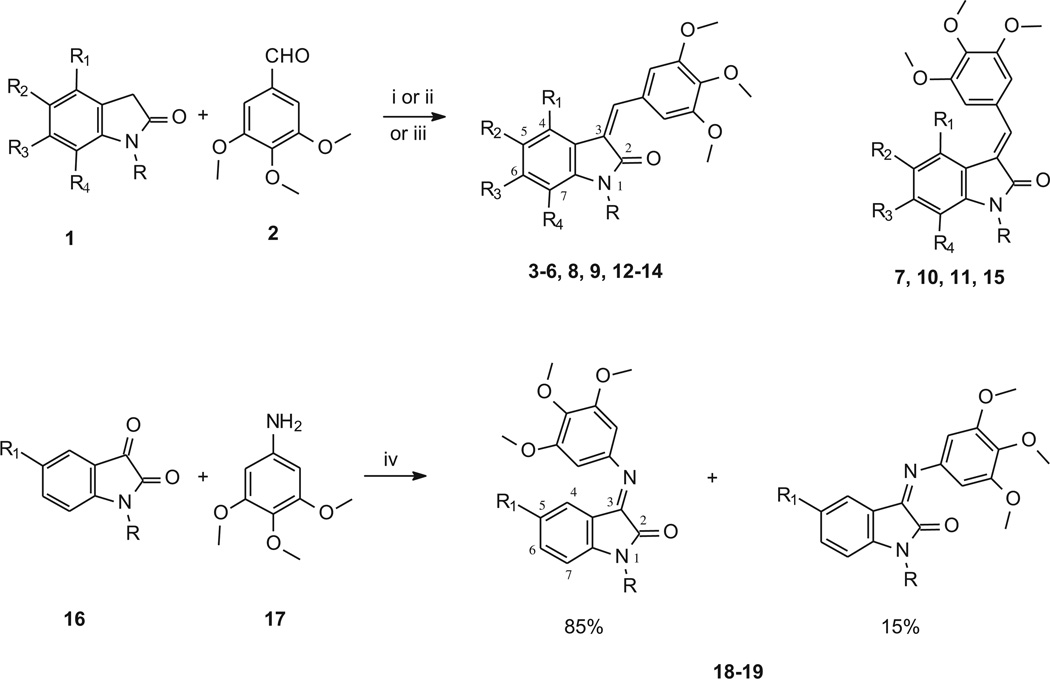

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzylidene)- and 3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)imino]-1,3-dihydroindol-2-ones derivatives.

aReagents and conditions: (i) methanol, piperidine; (ii) acetic acid, 37% HCl; (iii) anhydrous sodium acetate, acetic acid; (iv) ethanol.

Compounds 7, 10 and 11 were prepared to evaluate the effect of the addition of a methyl group at the 6 position (7) or at the nitrogen (10, 11), in order to compare their activity with those of NSC 736802 and NSC 134544. Moreover, considering that, as observed for compound NSC 736804, the presence a bulky substituent at the oxindole nitrogen is tolerated, substituted benzyl groups were introduced at the nitrogen (compounds 13–15). This type of substitution gave good cytotoxicity results when performed in other indolinone derivatives that we had studied previously [2,3]. Meanwhile, studies examining introduction of new substituents, such as bromine, dimethylamino, or trifluoromethyl, and exploration of different positions for the oxindole ring were also undertaken (compounds 3–6, 8 and 9). Finally, we took into consideration the replacement of the methine bridge linking the oxindole and the 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzene with an imino group (compounds 18, 19).

The cytotoxic activities of all new compounds were evaluated according to Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP), National Cancer Institute (NCI), Bethesda, MD, drug screen protocols. We also studied two possible mechanisms of action: inhibition of tubulin assembly and inhibition of NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4).

It is well known that anticancer agents such as colchicine and combretastatin A-4 interfere with the dynamic equilibrium of microtubules by inhibition of tubulin polymerization. Moreover 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylthioindoles, along with the corresponding ketone and methylene analogs, have been described as tubulin assembly inhibitors [4]. The structural analogy prompted us to test compounds 3–19 and derivatives reported in Chart 1 as inhibitors of tubulin polymerization.

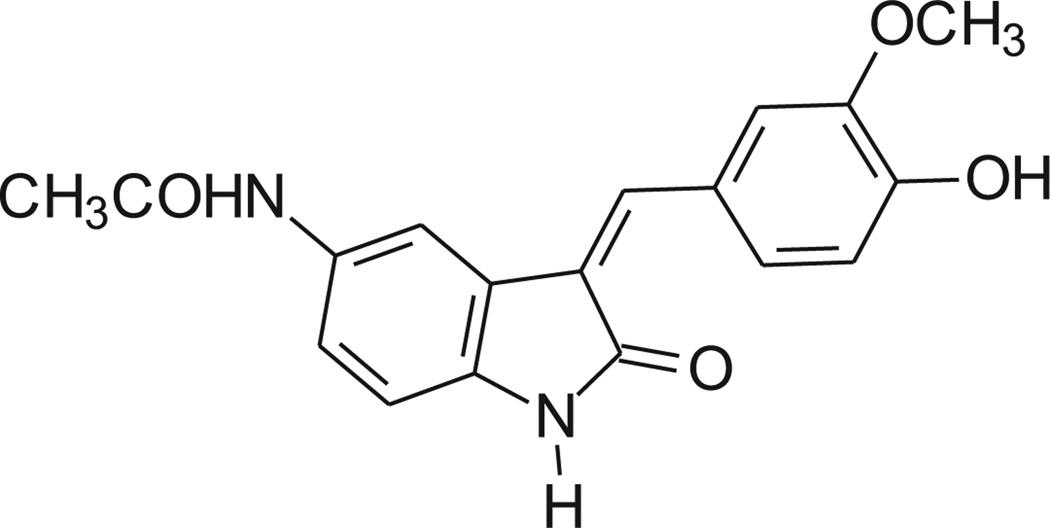

Recently, the Nox4 inhibitory activity shown by some oxindole derivatives was described [5]. The chemical structure of the most active compound 9d is shown in Chart 2. As in our 3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzylidene)-1,3-dihydroindol-2-ones, the indolinone moiety is linked to a substituted phenyl ring by means of a methine bridge. We therefore decided to determine whether Nox4 was a possible target for the compounds described here.

Chart 2.

Potent Nox4 inhibitor described as 9d in Ref. [5].

NAD(P)H oxidase enzymes (Nox) constitute a family of structural homologs of phagocytic Nox (Nox2 or gp91phox) and are one of the major sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in many cell types [6,7]. It is well known that ROS can act as messengers in cellular signaling transduction pathways and that an increase of ROS supports cellular growth and proliferation, contributing to cancer development [8]. In addition, accumulating evidence suggests that specific Nox isoforms, in particular Nox4, are associated with ROS production and proliferation of cancer cells. The ROS generated by this enzyme have been implicated in numerous biological functions, including signal transduction, cell differentiation and tumor cell growth. ROS produced by Nox4 in pancreatic cancer has been shown to transmit cell survival signals via the AKT-ASK1 pathway, while inhibition of Nox4 activates apoptosis [9]. It has been demonstrated that Nox4 overexpression plays an oncogenic role in breast tumorigenesis and that treatment of Nox4 overexpressing cells with catalase resulted in decreased tumorigenicity [10]. In glioblastoma multiforme, cycling hypoxia triggers ROS production via Nox4, and this is associated with increased tumor cell growth in vitro and in mouse xenografts. Inhibition of Nox4 with siRNA or antioxidant in vitro and Nox4 knockdown in mice were able to block cell growth or tumor progression [11]. Moreover, it has been shown that Nox4 derived ROS are required for proliferation of acute leukemia cells, and inhibition of Nox or siRNA against Nox4 resulted in a decrease in intracellular ROS and decreased cell viability [12]. Nox4 is also the main isoform in endothelial cells (ECs) [13], and it plays an important role in angiogenesis [14]. Since angiogenesis in cancer is essential for tumor growth and metastasis, the inhibition of specific Nox isoforms has been proposed as a therapeutic strategy for treatment of cancer and other angiogenesis-dependent pathologies [15].

| Compd | R | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | H | OCH3 | H | H | OCH3 |

| 4 | H | Cl | H | H | Cl |

| 5 | H | H | Br | H | H |

| 6 | H | H | N(CH3)2 | H | H |

| 7 | H | H | OH | CH3 | H |

| 8 | H | H | H | Cl | H |

| 9 | H | H | H | OCF3 | H |

| 10 | CH3 | H | OH | H | H |

| 11 | CH3 | H | OCH3 | H | H |

| 12 | CH3 | H | Cl | H | H |

| 13 | CH2–(C6H4) –pCl | H | H | H | H |

| 14 | CH2– (C6H4) –pOCH3 | H | H | H | H |

| 15 | CH2– (C6H4) –pOCH3 | H | OCH3 | H | H |

| 18 | H | OCH3 | – | – | – |

| 19 | CH2–C6H5 | H | – | – | – |

2. Chemistry

Compounds 3–15 (Scheme 1, Table 1) were synthesized by means of the Knoevenagel reaction between 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde and the appropriate oxindole. The reaction was performed in methanol in the presence of piperidine (Method A). The only exceptions were compounds 9 and 15: the former was prepared in AcOH/HCl (Method B) and the latter in AcOH/AcONa (Method C).

Table 1.

Compounds 3–15, 18, 19.

| Comp. | Formula | MW | Method | Mp °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | C20H21NO6 | 371.39 | A | 138–140 |

| 4 | C18H15Cl2NO4 | 380.22 | A | 210–212 |

| 5a | C18H16BrNO4 | 390.23 | A | 255–256 |

| 6 | C20H22N2O4 | 354.40 | A | 188–190 |

| 7 | C19H19NO5 | 341.36 | A | 160–163 |

| 8 | C18H16ClNO4 | 345.78 | A | 260–262 |

| 9 | C19H16F3NO5 | 395.33 | B | 195–197 |

| 10 | C19H19NO5 | 341.36 | A | 175–180 |

| 11 | C20H21NO5 | 355.39 | A | 120–124 |

| 12 | C19H18ClNO4 | 359.81 | A | 102–105 |

| 13 | C25H22ClNO4 | 435.90 | A | 135–137 |

| 14 | C26H25NO5 | 431.48 | A | 100–105 |

| 15 | C27H27NO6 | 461.51 | C | 115–120 |

| 18 | C18H18N2O5 | 342.35 | – | 180–182 |

| 19 | C24H22N2O4 | 402.44 | – | 125–130 |

Compound described in Ref. [16] but not fully characterized.

The imino-derivatives 18 and 19 were obtained by reacting the properly substituted isatin with 3,4,5-trimethoxyaniline.

The 1H NMR spectra are in agreement with the assigned structures.

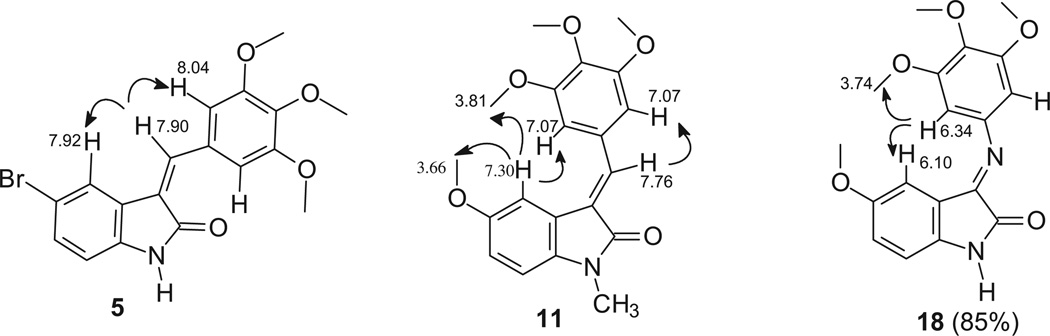

Geometrical configuration was determined by performing NOE experiments on some of the synthesized derivatives in order to evaluate whether the methine bridge and the proton at the 4 position of the indole (ind-4) are close in space (Z configuration) or not (E configuration).

Compounds 3, 5, 6, 13 and 14 were found to be Z isomers. In fact, after irradiation of the methine bridge, NOE was observed not only on protons at positions 2′and 6′of the phenyl group, but also on the proton (or group) at position 4 of the indole. As an example, NOE connectivities found in compound 5 are reported in Chart 3.

Chart 3.

NOE connectivities in compounds 5, 11 and 18.

On the other hand, NOE experiments on compounds 7 and 11 showed that they were E isomers.

For compound 7, first it was necessary to perform some NOE experiments in order to assign the aromatic singlets. Irradiation of the methyl at position 6 of the indole (2.10 ppm) gave NOE at 6.58 ppm. This singlet was thus assigned to the indole proton at the 7 position (ind-7). Afterward, irradiation of the singlet at 7.42 ppm gave NOE only at phenyl protons (7.00 ppm) and not at OH. As a consequence, the singlet at 7.42 ppm was assigned to the methine bridge and the one at 7.32 ppm to ind-4. This last NOE experiment was also in agreement with the E configuration because it excluded the spatial proximity of the methine bridge and ind-4. The E configuration was also confirmed through irradiation of the phenyl protons at 7.00 ppm. In fact, NOE was observed not only at the methine bridge, but also at ind-4, thus revealing the spatial closeness of the phenyl protons and ind-4.

For compound 11, two NOE experiments were performed (see Chart 3), both in agreement with the E configuration: i) irradiation of ind-4 (7.30 ppm) gave NOE at 3.66 ppm (indole OCH3), at 3.81 ppm (phenyl OCH3) and at 7.07 ppm (phenyl protons); ii) irradiation of the methine bridge (7.66 ppm) gave NOE only at the phenyl protons (7.07 ppm).

The geometrical configuration of compounds 4, 8–10, 12, 15 was assigned by comparing the signals of the 1H NMR spectra, since we noticed that in E isomers protons at positions 2′and 6′of the trimethoxyphenyl ring gave a singlet at about 7 ppm, whereas in Z isomers the singlet was around 8 ppm.

As far as the imino derivatives 18 and 19 are concerned, they were obtained as mixtures of E (85%) and Z (15%) isomers by refluxing 3,4,5-trimethoxyaniline and the appropriate isatin in ethanol. The configuration of the prevalent isomer was determined by means of NOE experiments. For both the compounds, irradiation of the protons at positions 2′and 6′of the phenyl ring gave NOE not only at the OCH3, but also at ind-4, thus confirming the E configuration (NOE connectivities observed in compound 18 are reported in Chart 3).

3. Biology

3.1. Cell-based assays

Compounds 3–19 were initially tested at a single high concentration (10−5 M) in the full NCI 60 cell panel (NCI 60 Cell One-Dose Screen). This panel is organized into subpanels representing leukemia, melanoma and cancers of lung, colon, kidney, ovary, breast, prostate and central nervous system. Only compounds which satisfy predetermined threshold inhibition criteria in a minimum number of cell lines will progress to the full 5-concentration assay. The threshold inhibition criteria for progression to the 5-concentration screen were selected to efficiently capture compounds with antiproliferative activity based on the analysis of historical DTP screening data. The result is expressed as the percent growth of treated cells relative to the control following a 48 h incubation. Twelve of fifteen evaluated compounds were active in the preliminary test and progressed to the five-concentration assay. The compounds were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and evaluated using five concentrations at ten-fold dilutions (the highest being 10−4 M) following a 48 h incubation. Table 2 reports the results obtained (vincristine is reported for comparison purposes), at three assay endpoints: 50% growth inhibition (GI50), total cytostatic effect (TGI = Total Growth Inhibition) and cytotoxic effect (LC50, loss of 50% of the initial cell protein). For some compounds, the 5-concentration test was repeated, and no significant differences were found. For these compounds, the data reported in Table 2 are the mean values of the two experiments.

Table 2.

Nine subpanels at five concentrations: growth inhibition, cytostatic and cytotoxic activity (µM) of 12 selected compounds.

| Comp.a | Modes | Leukemia | NSCLC | Colon | CNS | Melanoma | Ovarian | Renal | Prostate | Breast | MG-MIDb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | GI50 | 2.6 | 7.1 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 4.3 |

| TGI | 14.1 | 25.1 | 15.5 | 20.4 | 18.6 | 23.4 | 18.6 | 22.9 | 19.0 | 19.5 | |

| LC50 | 79.4 | 74.1 | 41.7 | 54.9 | 44.7 | 77.6 | 54.9 | 58.9 | 64.6 | 58.9 | |

| 5c | GI50 | 2.1 | 9.5 | 6.2 | 14.8 | 10.2 | 17.0 | 14.1 | 11.0 | 3.2 | 7.9 |

| TGI | 49.0 | 77.6 | – | 56.2 | 76.0 | 69.2 | 75.9 | – | 45.7 | 67.6 | |

| 6c | GI50 | 1.1 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.8 |

| TGI | 9.3 | 41.7 | 34.7 | 25.1 | 42.7 | 32.4 | 49.0 | 43.6 | 37.1 | 32.4 | |

| LC50 | 81.3 | – | 81.3 | 81.3 | – | 81.3 | 83.2 | – | – | 89.1 | |

| 7c | GI50 | 1.8 | 5.7 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 3.6 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 2.5 | 4.3 |

| TGI | 8.7 | 31.6 | 18.2 | 25.7 | 16.6 | 37.1 | 25.1 | 30.9 | 14.4 | 20.9 | |

| LC50 | 70.8 | 79.4 | 53.7 | 85.1 | 53.7 | 87.1 | 66.1 | 91.2 | 74.1 | 69.2 | |

| 8c | GI50 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| TGI | 3.6 | 8.3 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 4.1 | 5.4 | |

| LC50 | 56.2 | 29.5 | 22.9 | 18.6 | 19.0 | 17.4 | 14.1 | 17.0 | 31.6 | 24.0 | |

| 9 | GI50 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 4.6 | 2.1 | 2.7 |

| TGI | 27.5 | 14.1 | 10.2 | 7.4 | 10.7 | 11.2 | 12.6 | 29.5 | 8.7 | 12.3 | |

| LC50 | – | 51.3 | 37.1 | 33.9 | 44.7 | 49.0 | 34.7 | 83.2 | 60.3 | 49.0 | |

| 10 | GI50 | 2.2 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 4.4 |

| TGI | 8.3 | 24.6 | 18.2 | 17.4 | 16.2 | 26.3 | 22.4 | 6.3 | 15.1 | 17.4 | |

| LC50 | 81.3 | 77.6 | 47.9 | 53.7 | 43.6 | 79.4 | 70.8 | 22.9 | 61.7 | 61.7 | |

| 11c | GI50 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| TGI | 7.6 | 46.8 | 16.6 | 14.1 | 21.9 | 28.2 | 24.0 | – | 21.9 | 21.9 | |

| LC50 | 87.1 | 83.2 | 63.1 | – | 85.1 | – | – | – | – | 89.1 | |

| 12 | GI50 | 2.3 | 7.4 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.5 |

| TGI | 14.4 | 28.2 | 18.2 | 24.5 | 21.4 | 36.3 | 24.0 | 11.2 | 17.4 | 21.4 | |

| LC50 | 67.6 | 85.1 | 67.6 | 81.3 | 69.2 | 93.3 | 85.1 | – | – | 81.3 | |

| 13c | GI50 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| TGI | 4.9 | 14.4 | 5.9 | 15.1 | 8.9 | 22.9 | 10.7 | 7.6 | 12.9 | 10.7 | |

| LC50 | 50.1 | 56.2 | 14.4 | 46.8 | 26.9 | 51.3 | 43.6 | 33.1 | 95.5 | 41.7 | |

| 14 | GI50 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| TGI | 27.5 | 9.3 | 3.6 | 10.5 | 4.5 | 21.4 | 9.1 | 26.3 | 17.4 | 9.3 | |

| LC50 | – | 38.9 | 8.3 | 26.3 | 19.5 | 67.6 | 45.7 | – | 93.3 | 35.5 | |

| 15c | GI50 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| TGI | 27.5 | 11.2 | 3.8 | 7.4 | 5.7 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 8.9 | |

| LC50 | – | 33.1 | 7.9 | 33.9 | 23.4 | 50.1 | 28.8 | 83.2 | 79.4 | 34.7 | |

| Vincristined | GI50 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| TGI | 15.8 | 15.8 | 4.0 | 6.3 | 7.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 6.3 | 7.9 | 10.0 | |

| LC50 | 630.9 | 251.2 | 79.43 | 199.5 | 251.2 | 316.2 | 251.2 | 316.2 | 316.2 | 251.2 |

Highest conc. = 10−4 M unless otherwise specified; only values <100 µM are reported. The compound exposure time was 48 h.

Mean Graph MIDpoint; i.e., the calculated panel mean.

Mean of two separate experiments.

Highest conc. = 10−3 M.

The tested compounds showed a mean GI50 range between 1.3 and 7.9 µM, and compounds 5, 8, 13 and 15 were submitted to the Biological Evaluation Committee of the NCI for possible future development.

The results obtained do not show a substantial difference in cytotoxic activity, on the basis of the geometrical configuration (E/Z). The substitution of the methine bridge with an imino group (18, 19) led to lack of cytotoxic activity, and the introduction of a methyl group at position 1 or 6 of the indolinone system (7, 10 and 12) did not improve activity. The introduction of a benzyl ring at position 1 (13–15) gave compounds endowed with a high cytotoxic activity, with GI50 values of 2.1–2.6 µM. Among the other substituents on the indole system, the most interesting was chlorine at the 6 position, since compound 8 was the most active in the whole series.

3.2. Inhibition of tubulin assembly

The compounds were evaluated for potential inhibition of tubulin assembly, in comparison with the potent colchicine site agent combretastatin A-4, and for their effects at 5 µM on the binding of [3H]colchicine to tubulin. In the assembly assay used, the IC50 is defined as the concentration of compound that inhibits by 50% the extent of assembly of 10 µM tubulin after a 20 min incubation at 30 °C.

Compound 19 showed growth inhibition versus RXF 393 (kidney cancer) cells as well as CCRF-CEM and RPMI-8226 (leukemia) and HOP-92 (non-small cell lung cancer) cells in the NCI 60 Cell One-Dose Screen (data not shown). Moreover, it had the greatest inhibitory effect on tubulin assembly (IC50, 3.3 ± 0.3 µM vs. 1.1 ± 0.1 µM for combretastatin A-4), but it was much less effective than combretastatin A-4 as an inhibitor of colchicine binding (31 ± 3% vs. 99% inhibition for combretastatin A-4). All other compounds had assembly IC50 values >20 µM, except for NSC 134544 (IC50, 6.1 ± 0.2 µM with 35 ± 3% inhibition of colchicine binding) and compound 8 (IC50 15 ± 0.8 µM). These results showed that there was no correlation between inhibition of tubulin assembly and cytotoxicity, since compound 19 gave poor inhibition of cell growth, whereas compound 8 caused significant cell death. An explanation for these findings with tubulin is in the modeling section.

3.2.1. Binding models delineate structural basis for activity with tubulin

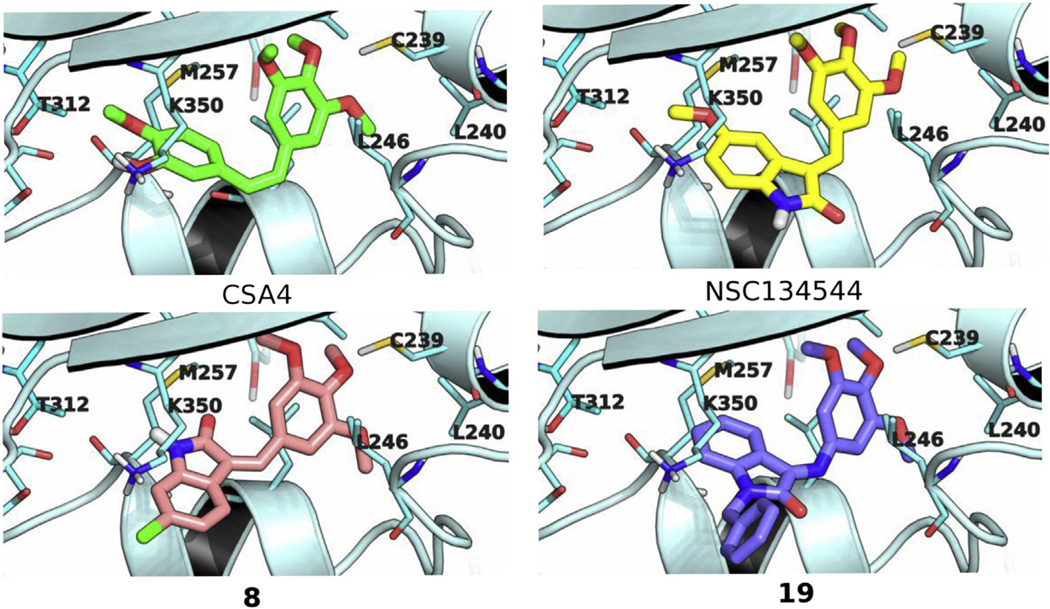

As depicted in Fig. 1, the modeled binding poses of NSC 134544, 8, and 19 occupied similar conformational space in the colchicine site of tubulin, as did the docked pose of CSA4. The trimethoxyphenyl moieties of NSC 134544, 8, and 19 each mapped similarly onto the trimethoxyphenyl motif of CSA4. At this segment of the colchicine site, the trimethoxy groups formed stabilizing hydrophobic interactions with the Leu240 and Leu246 side chains and, simultaneously, stabilizing polar interactions with the thiol of Cys239. At the other segment of the colchicine site, NSC 134544, 8, and 19 differed in their molecular components that packed onto the hydrophobic patch formed by the side chains of Met257, Thr312, and Lys350. For NSC 134544, its indolinone motif was directed toward this hydrophobic patch with its methoxy group wedged against the hydrophobic side chain of Met257 at the interior of the binding pocket. In contrast, for compound 8, its inverted E/Z stereochemistry relative to NSC 134544 resulted in a flip of its indolinone motif relative to that of NSC 134544. The aryl portion of the 8 indolinone was solvent exposed, in contrast to that of NSC 134544. However, in this alternative orientation, the indolinone of compound 8 retained favorable contacts with tubulin. As delineated in the model, the 8 indolinone moiety was packed lengthwise against the Lys350 side chain, with the arylchloro group of 8 making a favorable terminal interaction with the γ-carbon of Lys350. Lastly, for compound 19, the indolinone group assumed a similar orientation as that of NSC 134544 with its aryl ring positioned toward the interior of the colchicine site. The N-substituted benzyl group of compound 19 was packed against the hydrophobic Lys350 side chain, and this hydrophobic contact contributed to its ligand binding affinity.

Fig. 1.

Binding models of CSA4, NSC 134544, 8, and 19 in the colchicine site. β-Tubulin is rendered in light blue ribbon with amino acid side chains shown in stick with carbon atoms colored cyan. CSA4, NSC 134544, 8, and 19 are depicted in stick with carbon atoms colored green, yellow, pink and purple, respectively. Nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur and chlorine atoms are colored blue, red, yellow, and green, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2.2. Structure–activity relationship

Besides delineating a structural basis for the antitubulin activity of NSC 134544, 8, and 19, the binding models may also explain the inactivity of their close congeners. Docking of compound 13, which differs from compound 19 by the addition of a para-chlorine group and inversion of the geometric isomer to Z, suggests that the inactivity of compound 13 may be due, at least in part, to the inversion of configuration of the double bond, which creates an incompatible molecular shape for the colchicine site, as well as to an additional para-chlorine group, which produces potentially unfavorable steric bulk. Furthermore, the inactivity of compound 15 may also be rationalized using the binding models, which predicted a markedly lower binding affinity for 15 as compared with 19. Compound 15 has two methoxy groups that are not present in the active congener 19. Modeling showed that the indolinone-attached methoxy group of compound 15 shifts the indolinone from the interior of the binding pocket relative to the analogous moiety of compound 19. This shift in the binding pose of compound 15 reduced the binding surface contacts between the indolinone aromatic ring and the Met257 side chain and concomitantly moves the N-substituted arylmethoxy group into a more solvent exposed position and, thus, lessens its binding affinity. Additionally, the displacement of the indolinone positioned the 4-methoxy in the benzyl ring against the amino group of Lys350, creating an unfavorable hydrophobic-polar contact between the two functionalities. While this hydrophobic-polar contact was slightly unfavorable in the static binding model, as indicated by a carbon-to-nitrogen distance of 4.2 Å, in the native dynamics of ligand binding, these two functionalities may be brought closer together due to the inherent conformational flexibility of the torsional bond angles of the Lys350 side chain and the –O–CH3 bonds of the methoxy group. This would result in highly unfavorable hydrophobic-polar contacts that should preclude efficient ligand binding.

Additionally, the binding model for compound 8 may explain the weaker activity of its close congener compound 9, which has a –OCF3 substituent at the 6-position rather than the –Cl group of 8. With 9, this –OCF3 group is positioned at the solvent front, making it possible to accommodate the additional four heavy atoms relative to the –Cl moiety. However, the binding space of the –OCF3 group is restricted by the Lys350 side chain. Highly unfavorable interactions between this side chain and the –OCF3 moiety can result from bond rotation between the oxygen atom and the CF3 group during binding dynamics. Thus, the Lys350 side chain may be a stereoelectronic hindrance to binding by 9 in the colchicine site.

3.3. Nox4 inhibition

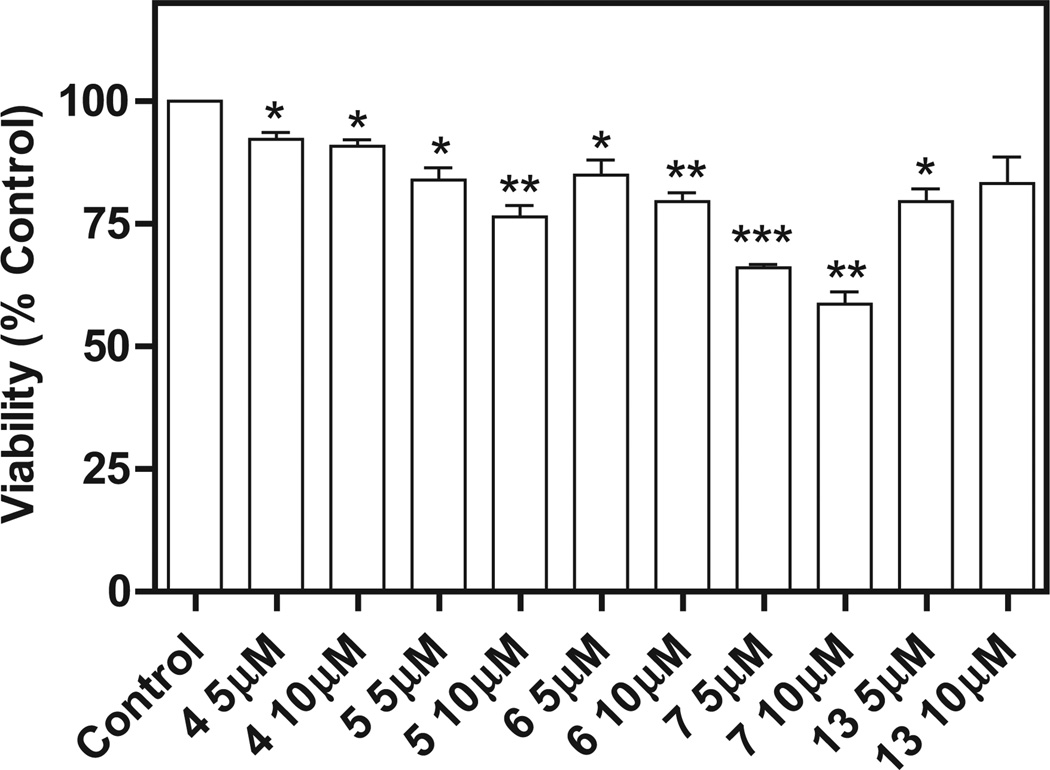

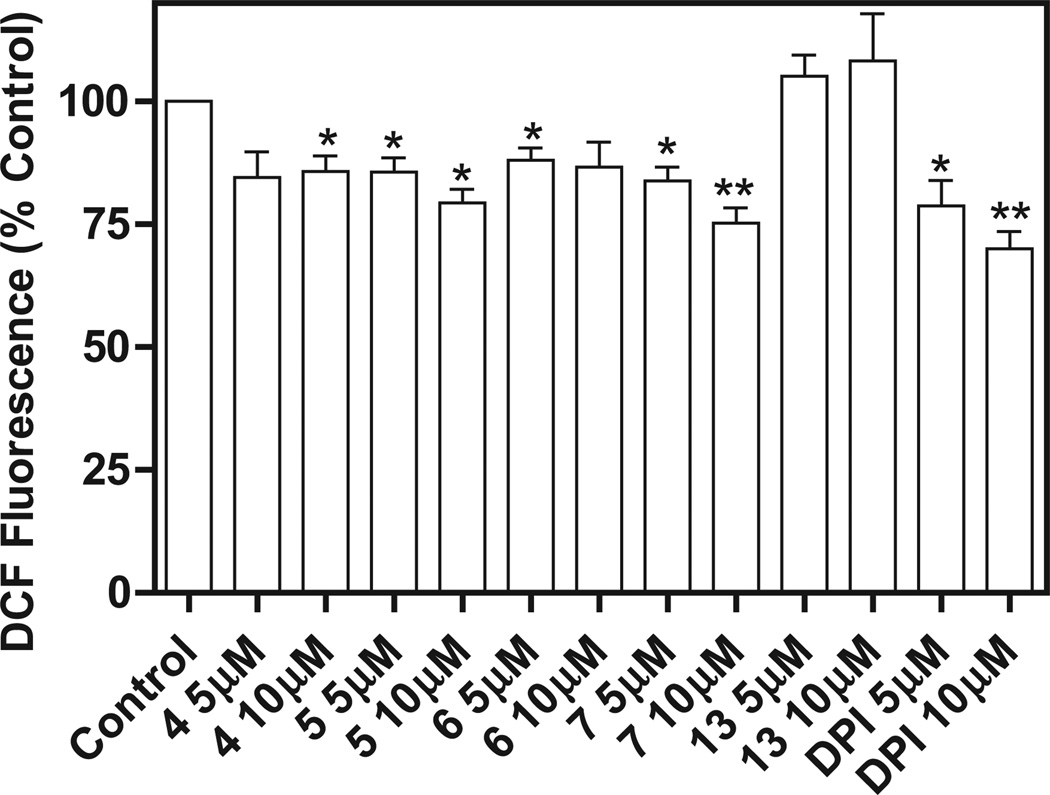

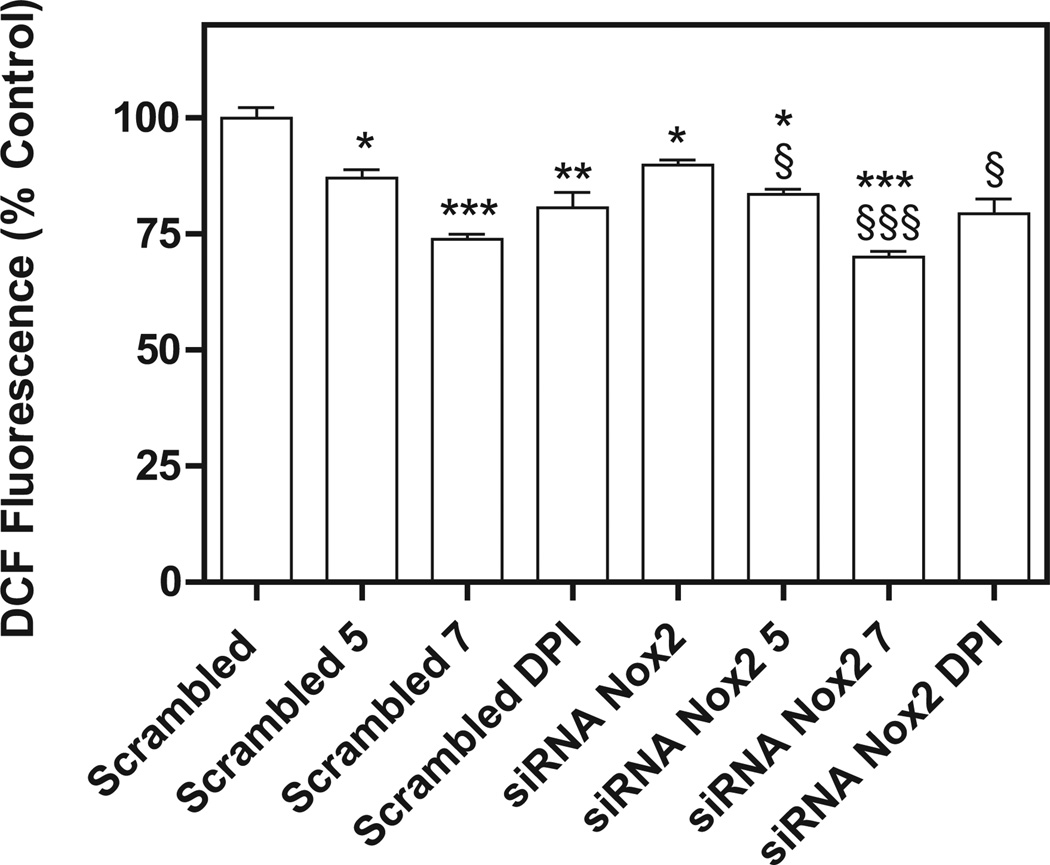

Compounds active against different NCI leukemia cell lines were tested for their ability to inhibit Nox4 in B1647 cells, a human acute myeloid leukemia cell line [12]. Compound 8 was not examined since measurement of ROS levels was not possible due to its intrinsic fluorescence. Nox4 is known to be constitutively active [17] and to play the major role in the generation of ROS required for sustaining cellular growth and proliferation of the B1647 cell line [12]. Initially, the cells were incubated with four compounds among the most effective against the NCI cell lines (5, 6, 7, and 13), and with compound 4 as a negative control, in order to assay the effect on viability after a 24 h treatment with the compounds at 5 or 10 µM. The MTT assay confirmed the antiproliferative activity of the 5 compounds (Fig. 2). Then, ROS production was measured in B1647 cells after a 30 min treatment with each compound at a concentration of 5 or 10 µM. We found that ROS generation was partially inhibited by the treatment with compounds 5 and 7 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3). As B1647 cells express Nox2 and Nox4 [18], in order to rule out the role of Nox2-derived ROS, the acute inhibition of ROS production was also measured following RNA silencing of Nox2. The data showed that both compounds 5 and 7 inhibited ROS production to the same extent either in Nox2 silenced cells or in the scrambled cells used as the control. These data confirmed the hypothesis that the ROS decrease was due to Nox4 inhibition (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Effect of compounds 4, 5, 6, 7 and 13 on viability of acute leukemia B1647 cells. Viable cells were evaluated by the MTT test. Cells (106 per well in 1 mL) were pretreated for 24 h with each compound dissolved in DMSO prior to adding 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT). MTT reduction was measured in a microplate reader. Results are averages of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 significantly different from the control.

Fig. 3.

Effect of compounds 4, 5, 6, 7, 13 and DPI on intracellular ROS level in B1647 cells. After a 30 min treatment with each compound dissolved in DMSO, cells (1 × 106/mL) were washed twice in PBS and incubated with 5 µM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin-diacetate (DCFH-DA) for 20 min at 37 °C. DCFH-DA is a small nonpolar, nonfluorescent molecule that diffuses into the cells where it is enzymatically deacetylated by intracellular esterases to the polar nonfluorescent compound, which is then oxidized to the fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF). The fluorescence of oxidized probes was measured in a multiwell plate. Results are averages of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 significantly different from control.

Fig. 4.

Effects of compounds 5, 7 and DPI on intracellular ROS after Nox2 silencing in B1647 cells. RNA interference experiments were performed as described in the Experimental section. Briefly, for transient siRNA transfection, B1647 cells were nucleofected with siRNA against Nox2 or nonspecific RNA (scrambled) at a final concentration of 50 nM. Intracellular ROS levels were measured as described in Fig. 3. The nonspecific control (scrambled) did not give a significant effect compared with the electroporated sample and was considered as control. Results are averages of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 significantly different from scrambled. §P < 0.05; §§§P < 0.001 significantly different from siRNA Nox2.

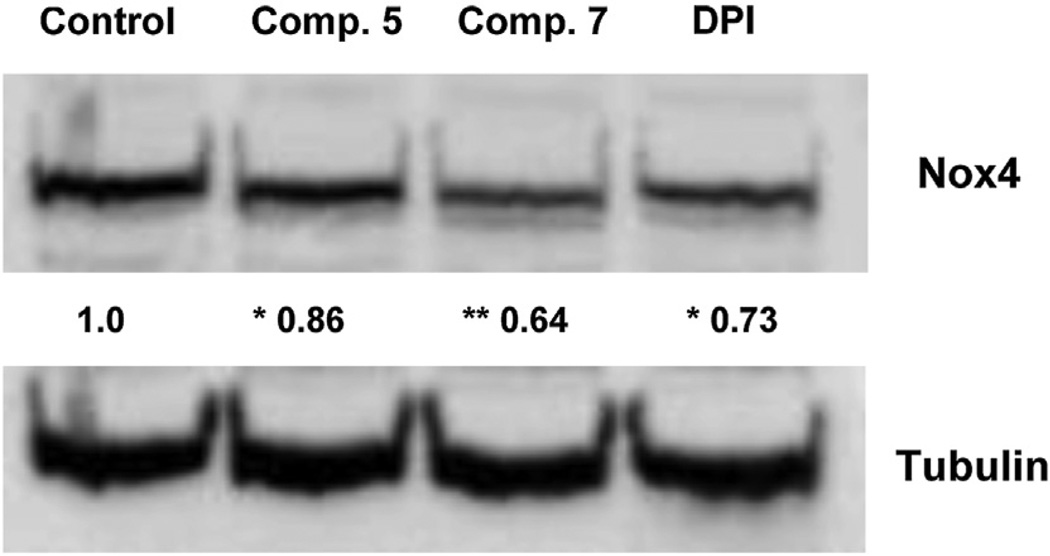

Finally, since recent evidence suggests that Nox4 could modulate its own expression and that a natural extract endowed with antioxidant activity is also able to downregulate Nox4, we investigated the potential effect on Nox4 expression exerted by compound 5 and 7 [19,20]. Western blotting analysis was performed with B1647 cells after a 24 h treatment with the two compounds. Data showed that treatments with compounds 5 and 7 were able to downregulate Nox4 expression (Fig. 5). Most notably, compound 7 inhibited ROS production and downregulated Nox4 more effectively than the nonspecific Nox inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium (DPI). In conclusion, our results indicate that Nox4 could be a target for compounds 5 and 7 and that Nox4 inhibition seems to contribute to their antiproliferative activity in acute leukemia B1647 cells. These compounds thus may have promise as a novel antileukemic therapy that attacks an unexploited target.

Fig. 5.

Nox4 expression in B1647 cells after a 24 h treatment with 5, 7 or DPI. Representative immunoblots showing Nox4 expression level in B1647 cells after a 24 h treatment with compounds 5, 7 or DPI (10 µM). 40 µg of protein per lane were electrophoresed and immunoblotted, as described in the Experimental section. Tubulin immunoblots confirm that each lane was loaded with the same amount of protein. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Relative amounts determined by scanning densitometry are expressed in arbitrary units. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 significantly different from control.

4. Conclusions

Biological data indicate that the growth-inhibiting activity of the compounds investigated was associated with both cytotoxic and cytostatic effects. Data obtained in the acute leukemia B1647 cell line revealed that Nox4 could be a target for compounds 5 and 7 contributing to their antiproliferative effect and suggested a potential role of these compounds in a novel multitarget antileukemic therapy. The antitubulin activity of the previously synthesized NSC 134544 was only observed in compounds 8 and 19, but cellular evidence (increased proportion of cells in G2/M) for this mechanism of action (data not presented) was only obtained for the more cytotoxic compound 8, which was less active than 19 with purified tubulin.

We conclude that Nox4 and tubulin assembly inhibition could explain, at least in part, the cytotoxic and cytostatic effects of the described compounds, which, however, probably act by means of further targets and, indeed, could have multiple targets. Molecules acting by means of multiple mechanisms could be useful for tackling the multifactorial nature of cancer.

5. Experimental section

5.1. Chemistry

All compounds synthesized had a purity of at least 95% as determined by combustion analysis. The melting points are uncorrected. TLC was performed on Bakerflex plates (Silica gel IB2-F) and column chromatography on Kieselgel 60 (Merck): the eluting solution was a mixture of petroleum ether/acetone in various proportions. The IR spectra were recorded in nujol on a Nicolet Avatar 320 E.S.P.; νmax is expressed in cm−1. The 1H NMR spectra were recorded in (CD3)2SO on a Varian MR 400 MHz (ATB PFG probe); the chemical shift (referenced to solvent signal) is expressed in δ (ppm) and J in Hz (abbreviations: ph = phenyl, bz = benzyl, ind = indole). 3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzaldehyde, 6-chloro-2-indolinone and 5-methoxy-isatin are commercially available, whereas 1-benzyl-isatin [21] and the other indolinones [22–31] were prepared according to the literature.

5.1.1. Synthesis of the 3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzylidene)-1,3-dihydroindol-2-ones

5.1.1.1. Method A (3–8, 10–14)

3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzaldehyde (10 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (100 mL) and treated with the equivalent of the appropriate indolinone and piperidine (1 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 1–6 h (according to a TLC test), and the precipitate formed on cooling was collected by filtration. Compounds 3–6, 8, 11–13 were crystallized from ethanol, 7 from acetone/petroleum ether and 10 from toluene (yield 20–40% for 3, 4, 6, 7, 10–12, 14, 60–70% for 5, 8, 13). Compound 14 was purified by column chromatography and crystallized from ethanol (yield 25%).

3. I.R.: 3165, 1690, 1573, 1112. 1H NMR: 3.70 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.75 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.81 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 3.87 (3H, s, OCH3 ind-4), 6.57 (1H, d, ind, J = 9), 6.85 (1H, d, ind, J = 9), 7.77 (2H, s, ph), 8.04 (1H, s, CH), 10.59 (1H, s, NH). Anal. Calcd for C20H21NO6 (MW 371.39): C, 64.68; H, 5.70; N, 3.77. Found: C, 64.57; H, 5.76; N, 4.02.

4. I.R.: 3181, 1685, 1568, 994. 1H NMR: 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.84 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 7.05 (1H, d, ind, J = 8.8), 7.29 (1H, d, ind, J = 8.8), 7.78 (2H, s, ph), 8.47 (1H, s, CH), 11.23 (1H, s, NH). Anal. Calcd for C18H15Cl2NO4 (MW 380.22): C, 56.86; H, 3.98; N, 3.68. Found: C, 56.94; H, 4.05; N, 3.55.

5. I.R.: 3145, 1701, 1573, 1127. 1H NMR: 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.85 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 6.80 (1H, d, ind-7 J = 8), 7.35 (1H, dd, ind-6, J = 8, J = 1.6), 7.90 (1H, s, CH), 7.92 (1H, d, ind-4, J = 1.6), 8.04 (2H, s, ph), 10.71 (1H, s, NH).

6. I.R.: 3155, 1685, 1578, 1122. 1H NMR: 2.87 (6H, s, 2× CH3), 3.75 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.85 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 6.67 (2H, m, ind), 7.20 (1H, d, ind-4, J = 2), 7.74 (1H, s, CH), 8.05 (2H, s, ph), 10.22 (1H, s, NH). Anal. Calcd for C20H22N2O4 (MW 354.40): C, 67.78; H, 6.26; N, 7.90. Found: C, 68.03; H, 6.03; N, 8.02.

7. I.R.: 3365,1680,1624,1127. 1H NMR: 2.10 (3H, s, CH3), 3.75 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.82 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 6.58 (1H, s, ind-7), 7.00 (2H, s, ph), 7.32 (1H, s, ind-4), 7.42 (1H, s, CH), 8.94 (1H, broad, OH),10.19 (1H, s, NH). Anal. Calcd for C19H19NO5 (MW 341.36): C, 66.85; H, 5.61; N, 4.10. Found: C, 67.02; H, 5.79; N, 3.94.

8. I.R.: 3135–3120, 1690, 1573. 1H NMR: 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.85 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 6.86 (1H, s, ind-7), 7.05 (1H, d, ind, J = 8), 7.69 (1H, d, ind, J = 8), 7.81 (1H, s, CH), 8.00 (2H, s, ph),10.73 (1H, s, NH). Anal. Calcd for C18H16ClNO4 (MW 345.78): C, 62.52; H, 4.66; N 4.05. Found: C, 62.77; H, 4.82; N, 3.97.

10. I.R.: 1690, 1634, 1578, 1009. 1H NMR: 3.14 (3H, s, CH3), 3.75 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.82 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 6.71 (1H, dd, ind-6, J = 8.4, J = 2.2), 6.85 (1H, d, ind-7, J = 8.4), 7.04 (2H, s, ph), 7.33 (1H, d, ind-4, J = 2.2), 7.60 (1H, s, CH), 9.18 (1H, s, NH). Anal. Calcd for C19H19NO5 (MW 341.36): C, 66.85; H, 5.61; N, 4.10. Found: C, 67.01; H, 5.73; N, 4.27.

11. I.R.: 1716, 1588, 1127, 717. 1H NMR: 3.17 (3H, s, CH3), 3.66 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.74 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.81 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 6.94 (1H, dd, ind-6, J = 8.8, J = 2.4), 6.97 (1H, d, ind-7, J = 8.8), 7.07 (2H, s, ph), 7.30 (1H, d, ind-4, J = 2.4), 7.66 (1H, s, CH). Anal. Calcd for C20H21NO5 (MW 355.39): C, 67.59; H, 5.96; N, 3.94. Found: C, 67.89; H, 6.03; N, 4.04.

12. I.R.: 1701, 1603, 1096, 815. 1H NMR: 3.21 (3H, s, CH3), 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.85 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 7.01 (1H, d, ind-7, J = 8.4), 7.32 (1H, dd, ind-6, J = 8.4, J = 2.2), 7.83 (1H, d, ind-4, J = 2.2), 7.93 (1H, s, CH), 8.06 (2H, s, ph). Anal. Calcd for C19H18ClNO4 (MW 359.81): C, 63.42; H, 5.04; N, 3.89. Found: C, 63.27; H, 4.98; N, 4.01.

13. I.R.: 1701, 1573, 1132, 723. 1H NMR: 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.87 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 5.02 (2H, s, CH2), 6.93 (1H, d, ind-7, J = 7.6), 7.07 (1H, t, ind, J = 7.6), 7.23 (1H, t, ind, J = 7.6), 7.34 (2H, d, bz, J = 9), 7.39 (2H, d, bz, J = 9), 7.77 (1H, d, ind-4, J = 7.6), 7.91 (1H, s, CH), 8.07 (2H, s, ph). Anal. Calcd for C25H22ClNO4 (MW 435.90): C, 68.88; H, 5.09; N, 3.21. Found: C, 69.01; H, 4.98; N, 3.44.

14. I.R.: 1685, 1568, 1127, 717. 1H NMR: 3.70 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.87 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 4.94 (2H, s, CH2), 6.88 (2H, d, bz, J = 8.6), 6.95 (1H, d, ind-7, J = 7.4), 7.05 (1H, t, ind-5, J = 7.4), 7.22 (1H, t, ind-6, J = 7.4), 7.27 (2H, d, bz, J = 8.6), 7.74 (1H, d, ind-4, J = 7.4), 7.89 (1H, s, CH), 8.07 (2H, s, ph). Anal. Calcd for C26H25NO5 (MW 431.48): C, 72.37; H, 5.84; N, 3.25. Found: C, 72.60; H, 5.69; N, 3.36.

5.1.1.2. Method B (9)

3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzaldehyde (10 mmol) was dissolved in acetic acid (50 mL) and treated with one equivalent of 6-trifluoromethoxy-2-indolinone and 37% HCl (1 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 20 h, and the precipitate formed on cooling was collected by filtration (yield 20%) and crystallized from ethanol.

9. I.R.: 3093, 1696, 1511, 994. 1H NMR: 3.75 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.85 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 6.77 (1H, s, ind), 6.99 (1H, d, ind, J = 8.3), 7.79 (1H, d, ind, J = 8.3), 7.86 (2H, s, ph), 8.01 (1H, s, CH), 10.79 (1H, s, NH). Anal. Calcd for C19H16F3NO5 (MW 395.33): C, 57.72; H, 4.08; N, 3.54. Found: C, 57.88; H, 3.99; N, 3.26.

5.1.1.3. Method C (15)

3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzaldehyde (15 mmol) was treated with one equivalent of 5-methoxy-1-(4-methoxybenzyl)-2-indolinone, 30 mmol of anhydrous sodium acetate and 130 mL of acetic acid. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 7 days, evaporated under reduced pressure and poured into ice water. The resulting precipitate was collected by filtration, purified by column chromatography and crystallized from ethanol (yield 30%).

15. I.R.: 1690, 1240, 1122, 717. 1H NMR: 3.63 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.70 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.74 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.81 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 4.87 (2H, s, CH2), 6.89 (4H, m, bz), 7.09 (2H, s, ph), 7.28 (3H, m, ind), 7.38 (1H, s, CH). Anal. Calcd for C27H27NO6 (MW 461.51): C, 70.27; H, 5.90; N, 3.03. Found: C, 69.98; H, 4.98; N, 2.89.

5.1.2. Synthesis of the 3-[(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)imino]-1,3-dihydroindol-2-ones 18, 19

3,4,5-Trimethoxyaniline (10 mmol) was dissolved in ethanol (100 mL) and refluxed for 3 h with one equivalent of the appropriate isatin. The precipitate formed on cooling was collected by filtration and crystallized from ethanol (18, yield 40%) or acetone/petroleum ether (19, yield 50%).

Data for 18. I.R.: 3140–3100, 1731, 1132. 1H NMR: 3.47 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.68 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.74 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 6.10 (1H, d, ind-4, J = 2.4), 6.34 (2H, s, ph), 6.82 (1H, d, ind-7, J = 8.4), 6.98 (1H, dd, ind-6, J = 8.4, J = 2.4), 10.77 (1H, s, NH). Anal. Calcd for C18H18N2O5 (MW 342.35): C, 63.15; H, 5.30; N, 8.18. Found: C, 63.03; H, 5.54; N, 8.03.

Data for 19. I.R.: 1711, 1578, 1127, 728. 1H NMR: 3.71 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.74 (6H, s, 2× OCH3), 4.99 (2H, s, CH2), 6.41 (2H, s, ph), 6.72 (1H, d, ind, J = 7.6), 6.86 (1H, t, ind, J = 7.6), 7.03 (1H, d, ind, J = 7.6), 7.35 (6H, m, 5bz + 1ind). Anal. Calcd for C24H22N2O4 (MW 402.44): C, 71.63; H, 5.51; N, 6.96. Found: C, 71.45; H, 5.67; N, 7.02.

5.2. Biology

5.2.1. Cell-based screening assay

The NCI screening is a two stage process [32], beginning with the evaluation of all compounds against the 60 cell lines at a single concentration of 10−5M. Compounds exhibiting significant growth inhibition were evaluated against the 60 cell panel at five concentration levels by the NCI according to standard procedures (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/btb/ivclsp.html). In both cases the exposure time was 48 h.

5.2.2. Inhibition of tubulin assembly

Combretastatin A-4 was a generous gift of Dr. G. R. Pettit, Arizona State University. Bovine brain tubulin was purified as described previously [33]. The tubulin assembly assay was performed with 10 µM tubulin and varying compound concentrations as described previously [34]. The IC50 is the compound concentration that inhibits extent of assembly after 20 min at 30 °C. The colchicine binding assay was performed with 1.0 µM tubulin, 5.0 µM [3H]colchicine and 5.0 µM inhibitor. Incubation was for 10 min at 37 °C. At this time point, about 40–60% maximum colchicine binding occurs in the control reactions. Details of the method were described previously [35].

5.2.2.1. Molecular modeling

The scientific program Maestro 9 (Schrödinger, LLC, New York) was used in this modeling study. Computer simulations were performed using the OPLS 2005 force-field, and a distance-dependent dielectric with a nonbonded interaction limited to within 13 Å. Minimizations involved up to 500 steps of Polak-Ribiere conjugate gradient.

The 3.58 Å 1SA0 crystal structure of αβ-tubulin in complex with DAMA-colchicine was selected as the template for docking studies. The β-tubulin subunit with bound DAMA-colchicine was extracted, and the amino acid sequence of β-tubulin was renumbered using as the basis the Uniprot code Q6B856 for bovine β-tubulin, which was the construct for the crystal structure. This was followed by transformation of bound DAMA–colchicine to colchicine. The β-tubulin–colchicine complex was refined using the standard protein preparation protocol in Maestro that allowed for energy minimization with a maximal deviation limited to 0.3 Å. Manual adjustment of the torsional bond angles of the Lys350 side chain optimized the colchicine site for docking studies. Subsequently, the protein–ligand complex was energy minimized with tethered restraints of 100 kcal to the polypeptide backbone. A docking grid for β-tubulin was created using bound colchicine as the reference molecule, and this grid was used as the template for modeling the reported binding poses.

As a reference, CSA4 was docked into the β-tubulin docking grid using the Glide program in Maestro. Among the binding poses, CSA4 assumed the expected conformation in the colchicine site, with its trimethoxyphenyl motif mapped onto that of colchicine and its arylhydroxyl motif mapped onto the tropolone functionality of colchicine. CSA4 gave a Glide XP docking score of −6.3, which indicates favorable binding. The docked poses of the active compounds 19 and 8 gave scores of −5.2 and −4.1, respectively. Additionally, consistent with experimental results, the docking program Glide gave a binding pose for compound 15 with a docking score of −3.7, which indicates markedly less binding affinity. Furthermore, the Glide program quantified a highly unfavorable docking score (>1000) for the binding pose of the inactive compound 13 that was modeled on the binding pose of the active congener 19.

5.3. Nox4 inhibition

5.3.1. Cell culture

Human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) B1647 cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere (37 °C, 5% CO2) in IMDM (PAA, Cölbe, Germany) supplemented with 5% human serum (PAA) [12].

5.3.2. Cell viability and proliferation

Viable cells were evaluated by the MTT assay. Cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL MTT (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 4 h at 37 °C. At the end of the incubation, purple formazan salt crystals were formed and dissolved by adding the solubilization solution (10% SDS, 0.01 M HCl), then the plates were incubated overnight in a humidified atmosphere (37 °C, 5% CO2). Absorption at 570 nm was measured in a multiwell plate reader (Wallac Victor2, Perkin–Elmer).

5.3.3. Measurement of intracellular ROS

Cells (1 × 106/mL) were washed twice in PBS and incubated with 5 µM DCFH-DA for 20 min at 37 °C. DCFH-DA is a small nonpolar, nonfluorescent molecule that diffuses into the cells where it is enzymatically deacetylated by intracellular esterases to a polar nonfluorescent compound that is in turn oxidized to the fluorescent DCF. The fluorescence of oxidized dye was measured in a multiwell plate reader (Wallac Victor2, Perkin–Elmer). DCFH-DA was purchased from Sigma– Aldrich.

5.3.4. RNA interference

For transient siRNA transfection, B1647 cells were nucleofected with Cell Line Nucleofector™ Kit C (Amaxa Biosystems, Cologne, Germany) program X-05 following the manufacturer’s instructions, with siRNA against Nox2 and Nox4 or nonspecific control siRNA (final siRNA concentration 50 nM). Oligos were obtained from Sigma-Genosys (Suffolk, UK). Specific oligos with maximal knockdown efficiency were selected among three different sequences for each gene. Subsequently, cells were immediately suspended in complete medium and incubated in a humidified 37 °C/5% CO2 incubator. After 24–48 h, cells were used in the following experiments: evaluation of Nox expression by Western blotting, detection of intracellular ROS levels and measurement of cell viability.

5.3.5. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed with a lysis buffer (1% Igepal, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM TLCK, 0.1 mM TPCK, 1 mM orthovanadate and protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 8.0) in ice for 15 min. Cell lysates were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel using a Mini-Protean II apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Proteins were transferred electrophoretically to a supported nitrocellulose membrane at 100 V for 90 min. Nonspecific binding to membrane was blocked by incubating the membrane in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)/Tween, pH 8.0, containing 5% non-fat dried milk for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the nitrocellulose membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. Blots were washed with TBS/Tween and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with secondary antibodies in TBS/Tween containing 5% non-fat dried milk. Membranes were washed with TBS/Tween and developed using Western Blotting Luminol Reagent. Anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and anti-Nox4 antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and anti-β-tubulin was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. Western Blotting Luminol Reagent was purchased from GE Healthcare (Buckinghamshire, UK).

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by a grant from the University of Bologna, Italy (RFO), and from MIUR (PRIN 2009).We are grateful to the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD) for the anticancer tests. We are grateful to Prof. Laura Landi for her scientific suggestions and comments, which have contributed to the performance of this study.

Abbreviations

- DTP

Developmental Therapeutics Program

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- CSA4

combretastatin A-4

- Nox

NAD(P)H oxidase enzyme

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- ECs

endothelial cells

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- GI

growth inhibition

- TGI

total growth inhibition

- LC

lethal concentration

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- DPI

diphenyleneiodonium

- DCFH-DA

2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin-diacetate

- DCF

2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein

- AML

human acute myeloid leukemia

References

- 1.Andreani A, Burnelli S, Granaiola M, Leoni A, Locatelli A, Morigi R, Rambaldi M, Varoli L, Kunkel MW. Antitumor activity of substituted E-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzylidene)-1,3-dihydroindol-2-ones. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:6922–6924. doi: 10.1021/jm0607808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreani A, Granaiola M, Leoni A, Locatelli A, Morigi R, Rambaldi M, Garaliene V, Farruggia G, Masotti L. Substituted E-3-(2-chloro-3-indolylmethylene)1,3-dihydroindol-2-ones with antitumor activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:1121–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreani A, Burnelli S, Granaiola M, Leoni A, Locatelli A, Morigi R, Rambaldi M, Varoli L, Calonghi N, Cappadone C, Farruggia G, Zini M, Stefanelli C, Masotti L. Substituted E-3-(2-chloro-3-indolylmethylene)1,3-dihydroindol-2-ones with antitumor activity. Effect on the cell cycle and apoptosis. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:3167–3172. doi: 10.1021/jm070235m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Regina G, Sarkar T, Bai R, Edler MC, Saletti R, Coluccia A, Piscitelli F, Minelli L, Gatti V, Mazzoccoli C, Palermo V, Mazzoni C, Falcone C, Scovassi AI, Giansanti V, Campiglia P, Porta A, Maresca B, Hamel E, Brancale A, Novellino E, Silvestri R. New arylthioindoles and related bioisosteres at the sulfur bridging group. 4. Synthesis, tubulin polymerization, cell growth inhibition, and molecular modeling studies. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:7512–7527. doi: 10.1021/jm900016t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borbély G, Szabadkai I, Horvath Z, Marko P, Varga Z, Breza N, Baska F, Vantus T, Huszar M, Geiszt M, Hunyady L, Buday L, Orfi L, Keri G. Small-molecule inhibitors of NADPH oxidase 4. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:6758–6762. doi: 10.1021/jm1004368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambeth JD, Krause KH, Clark RA. NOX enzymes as novel targets for drug development. Semin. Immunopathol. 2008;30:339–363. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelicano H, Carney D, Huang P. ROS stress in cancer cells and therapeutic implications. Drug Resist. Updates. 2004;7:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mochizuki T, Furuta S, Mitsushita J, Shang WH, Ito M, Yokoo Y, Yamaura M, Ishizone S, Nakayama J, Konagai A, Hirose K, Kiyosawa K, Kamata T. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase 4 activates apoptosis via the AKT/apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 pathway in pancreatic cancer PANC-1 cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:3699–3707. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham KA, Kulawiec M, Owens KM, Li X, Desouki MM, Chandra D, Singh KK. NADPH oxidase 4 is an oncoprotein localized to mitochondria. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010;10:223–231. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.3.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh CH, Shyu WC, Chiang CY, Kuo JW, Shen WC, Liu RS. NADPH oxidase subunit 4-mediated reactive oxygen species contribute to cycling hypoxia-promoted tumor progression in glioblastoma multiforme. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maraldi T, Prata C, Caliceti C, Vieceli Dalla Sega F, Zambonin L, Fiorentini D, Hakim G. VEGF-induced ROS generation from NAD(P)H oxidases protects human leukemic cells from apoptosis. Int. J. Oncol. 2010;36:1581–1589. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goettsch C, Goettsch W, Muller G, Seebach J, Schnittler HJ, Morawietz H. Nox4 overexpression activates reactive oxygen species and p38 MAPK in human endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;380:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craige SM, Chen K, Pei Y, Li C, Huang X, Chen C, Shibata R, Sato K, Walsh K, Keaney JF., Jr NADPH oxidase 4 promotes endothelial angiogenesis through endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation. Circulation. 2011;124:731–740. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.030775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ushio-Fukai M, Nakamura Y. Reactive oxygen species and angiogenesis: NADPH oxidase as target for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balderamos M, Ankati H, Kumar Akubathini S, Patel AV, Kamila S, Mukherjee C, Wang L, Biehl ER, D’Mello SR. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship studies of 3-substituted indolin-2-ones as effective neuroprotective agents. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008;233:1395–1402. doi: 10.3181/0805-RM-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nisimoto Y, Jackson HM, Ogawa H, Kawahara T, Lambeth JD. Constitutive NADPH-dependent electron transferase activity of the Nox4 dehydrogenase domain. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2433–2442. doi: 10.1021/bi9022285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prata C, Maraldi T, Fiorentini D, Zambonin L, Hakim G, Landi L. Noxgenerated ROS modulate glucose uptake in a leukaemic cell line. Free Radic. Res. 2008;42:405–414. doi: 10.1080/10715760802047344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haurani MJ, Cifuentes ME, Shepard AD, Pagano PJ. Nox4 oxidase over-expression specifically decreases endogenous Nox4 mRNA and inhibits angiotensin II-induced adventitial myofibroblast migration. Hypertension. 2008;52:143–149. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ugusman A, Zakaria Z, Hui CK, Nordin NA. Piper sarmentosum inhibits ICAM-1 and Nox4 gene expression in oxidative stress-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011;16:11–31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katritzky AR, Fan W-Q, Liang De-S, Li Q-L. Novel dyestuffs containing dicyanomethylidene groups. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1989;26:1541–1545. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta LK, Parrick J, Payne F. Preparation of 3-ethyloxindole-4,7-quinone. J. Chem. Res. S. 1998:190–191. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva BV, Ribeiro NM, Pinto AC, Vargas MD, Dias LC. Synthesis of ferrocenyl oxindole compounds with potential anticancer activity. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2008;19:1244–1247. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andreani A, Granaiola M, Leoni A, Locatelli A, Morigi R, Rambaldi M, Garaliene V. Synthesis and antitumor activity of 1,5,6-substituted 3-(2-chloro-3-indolylmethylene)1,3-dihydroindol-2-ones. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:2666–2669. doi: 10.1021/jm011123c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter JC, Robinson R, Wyler M. Monothiophthalimide and some derivatives of oxindole. J. Chem. Soc. 1941:620–624. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minisci F, Galli R, Cecere M. Amminazione Radicalica di Composti Aromatici Attivati: Acetammidi. Nuovo Processo per la Sintesi di para-Ammino-N, N-dialchilaniline. La Chim. e ’Industria. 1966;48:1324–1326. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen T, Madsen R. Ruthenium-catalyzed alkylation of oxindole with alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:3990–3992. doi: 10.1021/jo900341w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poondra RR, Turner NJ. Microwave-assisted Sequential amide bond formation and intramolecular amidation: a rapid entry to functionalized oxindoles. Org. Lett. 2005;7:863–866. doi: 10.1021/ol0473804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huisgen R, Konig H, Lepley AR. Nucleophilic aromatic substitutions. XVIII. New ring closures through arynes. Chem. Ber. 1960;93:1496–1506. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andreani A, Burnelli S, Granaiola M, Leoni A, Locatelli A, Morigi R, Rambaldi M, Varoli L, Landi L, Prata C, Vieceli Dalla Sega F, Caliceti C, Shoemaker RH. Antitumor activity and COMPARE analysis of bis-indole derivatives. Biorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:3004–3011. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun L, Tran N, Tang F, App H, Hirth P, McMahon G, Tang C. Synthesis and biological evaluations of 3-substituted indolin-2-ones: a novel class of tyrosine kinase inhibitors that exhibit selectivity toward particular receptor tyrosine kinases. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:2588–2603. doi: 10.1021/jm980123i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monks A, Scudiero D, Skehan P, Shoemaker R, Paull K, Vistica D, Hose C, Langley J, Cronise P, Vaigro-Wolff A, Gray-Goodrich M, Campbell H, Mayo J, Boyd M. Feasibility of a high-flux anticancer drug screen using a diverse panel of cultured human tumor cell lines. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1991;83:757–766. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.11.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamel E, Lin CM. Separation of active tubulin and microtubule-associated proteins by ultracentrifugation, and isolation of a component causing the formation of microtubule bundles. Biochemistry. 1984;23:4173–4184. doi: 10.1021/bi00313a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamel E. Evaluation of antimitotic agents by quantitative comparisons of their effects on the polymerization of purified tubulin. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2003;38:1–21. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verdier-Pinard P, Lai J-Y, Yoo H-D, Yu J, Marquez B, Nagle DG, Nambu M, White JD, Falck JR, Gerwick WH, Day BW, Hamel E. Structure-activity analysis of the interaction of curacin a, the potent colchicine site antimitotic agent, with tubulin and effects of analogs on the growth of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:62–67. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]