Abstract

We have previously demonstrated that diminazene aceturate (DIZE), a putative angiotensin 1–7 converting enzyme activator, protects rats from monocrotaline (MCT)-induced pulmonary hypertension (PH). The present study was conducted to determine if the beneficial effects of DIZE are associated with improvements in autonomic nervous system (ANS) modulation. PH was induced in male rats by a single subcutaneous injection of MCT (50mg/kg). A subset of MCT rats were treated with DIZE (15mg/kg/day) for a period of 21 days, after which the ANS modulation was evaluated by spectral and symbolic analysis of heart rate variability (HRV). MCT administration resulted in a significant (P<0.001) increase in the right ventricular systolic pressure (62±14mmHg) when compared with other experimental groups (Control: 26±6; MCT+DIZE: 31±7mmHg), while DIZE treatment was able to decrease this pressure. Furthermore MCT-treated rats had significantly reduced total power of HRV than the controls. On the other hand, although not significant, a trend towards increased HRV was observed in the MCT+DIZE group (Control: 108±47; MCT: 12±8.86 and MCT+DIZE: 40±14), suggesting an improvement of the cardiac autonomic modulation. This observation was further confirmed by the low-frequency/high-frequency index of spectral analysis (Control: 0.74±0.62; MCT: 1.45±0.78 and MCT+DIZE: 0.34±0.49) which showed that DIZE treatment was able to recover the ANS imbalance observed in the MCT-induced pulmonary hypertensive rats. Collectively, our results demonstrate that MCT-induced PH is associated with a significant increase in sympathetic modulation and a decrease in HRV, which are markedly improved by DIZE treatment.

Keywords: DIZE, Pulmonary hypertension, Autonomic modulation, Sympathetic system, Parasympathetic system, ACE2, Diminazene, Autonomic nervous system

1. Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a fatal lung disease that negatively affects the patient's quality of life. Endothelial dysfunction, vasodilator/vasoconstrictor imbalance (Bradford et al., 2010) and disturbances in the autonomic nervous system (ANS) (Dimopoulos et al., 2009; Wensel et al., 2009) are some of the known factors that have been linked to the pathogenesis of PH. Although considerable efforts have been directed towards understanding the physiopathology of PH, management and cure of this disease still remains elusive.

Recent evidences suggest that PH may be associated with changes in heart rate (HR) dynamics. Studies involving pulmonary hypertensive patients have shown either an increase (Sanyal and Ono, 2002) or decrease (Hessel et al., 2006) in the HR mean value. On the other hand, it is widely recognized that PH is associated with increased sympathetic tone (Ciarka et al., 2007; Velez-Roa et al., 2004). Also, numerous studies have revealed a reduced spectral power of HR variability (HRV) (Sanyal and Ono, 2002) and increased low-frequency (LF) versus high-frequency (HF) spectral power ratio (LF/HF ratio) in pulmonary hypertensive subjects (Rosas-Peralta et al., 2006). These findings suggest that the cardiac ANS modulation is altered in PH, resulting in an increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic modulation. All of these changes can have profound effects on many organ systems leading to disease severity (Gillman et al., 1993).

Clinically, ANS function can be easily evaluated by performing HR measurements in the supine position or during postural changes (Petrofsky et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 1966). The ECG is a low cost diagnostic tool that provides essential information about Q-T series (Molnar et al., 1997). Moreover, the spectral and symbolic analyses are simple methods that would allow the physicians and researchers to collect valuable information about ANS modulation. Measurement of the ANS function in PH patients may be clinically relevant, since an improvement in the ANS modulation could potentially lower the risk factors for adverse cardiovascular events (Gillman et al., 1993).

Experimental studies from our group have demonstrated that diminazene aceturate (DIZE) treatment significantly prevented the development of PH probably due to an increase in the vasoprotective axis of the lung renin-angiotensin system, decreased inflammatory cytokines, improved pulmonary vasoreactivity and enhanced cardiac functions. These beneficial effects were abolished by C-16, an ACE2 inhibitor. Furthermore, initiation of DIZE treatment after the induction of PH arrested disease progression (Shenoy et al., 2013). DIZE is structurally similar to the previously reported angiotensin-(1–7) converting enzyme (ACE2) activator compond XNT, (1-[(2-dimethylamino) ethylamino]-4-(hydroxymethyl)-7-[(4-methylphenyl) sulfonyl oxy]-9H-xanthene-9-one), but has better physicochemical characteristics. Therefore, we hypothesized is that DIZE activates ACE2 to directly or indirectly modulate the cardiac ANS to produce its beneficial effects.

Despite the fact that autonomic nervous system imbalance is a common finding of many diseases, its treatment is still unmentioned. Moreover, once the right ventricular is the major determinants of the functional capacity and prognosis of the PH, the relevance of evaluating the ANS function in PH and the evidence that angiotensin converting enzyme 2 plays a key role in the physiopathology of this disease (Ferreira et al., 2009), our goal was to investigate whether DIZE, an ACE2 activator (Gjymishka et al., 2010), improves the autonomic modulation in the MCT-model of PH using the spectral and symbolic analysis methods. MCT-induced PH has been extensively used as a hemodynamically relevant animal model to study this disease. This model mimics several key aspects of the human disorder (Werchan et al., 1989).

We propose that DIZE treatment of the pulmonary hypertensive rats will not only decrease the sympathetic modulation and the sympathetic/parasympathetic ratio, but also reduce the ANS dysfunction and pulmonary pressure.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animals

Seven-week old male Sprague Dawley rats were housed in a temperature-controlled room (25 ± 1°C) and were maintained on a 12:12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to water and food. All procedures involving experimental animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida and complied with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

2.2 MCT-induced Pulmonary Hypertension and DIZE or saline treatment

PH was induced in two groups of rats by a single subcutaneous injection of MCT (50 mg/kg). One group was co-treated with DIZE subcutaneously (15mg/kg/day) for 21 days. The other experimental group was age matched control rats that were injected daily with saline (500µl, subcutaneously).

2.3 Cardiovascular evaluation

All the procedures and measurements were carried out on anesthetized rats. The right ventricular systolic pressure was measured using a silastic catheter inserted into the right descending jugular vein and advanced to the right ventricle, under the influence of a rodent anesthetic cocktail comprising of ketamine (70mg/kg), xylazine (8mg/kg), and acepromazine (1.5mg/kg).

The data were recorded (4000Hz/sample rate) after stabilization of the tracing using a liquid pressure transducer, which was interfaced to a PowerLab (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) signal transduction unit. The appearance of a waveform was used to confirm the positioning of the catheter in the right ventricle. Data were analyzed by using the Chart program supplied along with the PowerLab system.

2.4 Autonomic evaluation

After detecting the pulse intervals, the heart period was automatically calculated on a beat-to-beat basis as the time interval between two consecutive systolic peaks or pulse interval (PI). All detections were carefully checked to avoid erroneous or missed beats. Sequences of 200–250 beats were randomly chosen (Dabire et al., 1998; Dias da Silva et al., 2006) and if they presented non-stationary episodes, they were discarded and a new random selection was performed. Stationarity of the series was tested as previously reported (Porta et al., 2004). Frequency domain analysis of HRV was performed with an autoregressive algorithm (Porta et al., 2004) on the PI interval sequences (tachogram). The power spectral density was calculated for each time series.

In this study, two spectral components were considered: low frequency (LF), from 0.25 to 0.75 Hz; and high frequency (HF), from 0.75 to 3.00 Hz (Dabire et al., 1998; Dias da Silva et al., 2006; Murasato et al., 1998; Soares et al., 2004; Waki et al., 2006). The spectral components (ms2) were expressed in absolute (a) and normalized (nu) units. Normalization consisted of dividing the power of a given spectral component by the total power, then multiplying the ratio by 100. In a reduced variability condition, linear methodologies have poor applicability (Montano et al., 1994). Thus, the non-linear approach provides a new perspective in the investigation of neural control of the cardiovascular system (Casali et al., 2008; Porta et al., 2008). Symbolic analysis is a powerful tool already validated to detect changes in autonomic modulation of cardiovascular variability (Guzzetti et al., 2005; Porta et al., 2007) that transforms a time series into short, three beat long patterns. The sequences are spread on six levels and all possible patterns are divided into four groups, consisting of patterns with: i) no variations (0V, three symbols equal); ii) one variation (1V, two symbols equal and one different); iii) two like variations (2LV); and iv) two unlike variations (2UV) (Guzzetti et al., 2005).

2.5 Statistical analysis

The method used for statistical analysis was the non-parametric variance test of Kruskal-Wallis, complemented by Dunn test. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Animals treated with MCT exhibited a significant increase in right ventricle systolic pressure when compared to control rats (table 1), while rats treated with DIZE showed a decrease in this pressure. Heart rate was not different among the experimental groups.

Table 1.

Right Ventricular Arterial Pressure (mmHg) and Heart Rate (bpm) measurements

| RVSP | HR | |

|---|---|---|

| CO (n=7) | 26±6 | 145±16 |

| MCT (n=6) | 62±14a | 153±60 |

| MCT+DIZE (n=6) | 31±7 | 209±48 |

Values represent means ± standard deviation; CO= control rats; MCT= rats treated with monocrotaline; MCT+DIZE= rats treated with monocrotaline and Diminazene Aceturate. RVSP = Right Ventricular Systolic Pressure; HR = heart rate in beats per minute;

P<0.05 vs CO and MCT+DIZE.

MCT treatment significantly decreased the total power of HRV, HFa and LFa versus control rats. Although not significant, there was a trend towards an increase in HFa, the parasympathetic component, when comparing MCT+DIZE with MCT group. However, DIZE treatment of MCT-treated rats resulted in a significant improvement in power spectrum parameters, such as LFnu, HFnu and LF/HF ratio, versus MCT alone group. MCT-treated rats have impaired cardiac ANS modulation and DIZE improves the ANS balance in favor to parasympathetic modulation. The significant and inverse proportion between HFnu and LFnu components observed in MCT+DIZE rats as compared to MCT alone group confirm these results.

In addition, in the MCT+DIZE group there was 19% of sympathetic and 81% of parasympathetic modulation to the heart. In the MCT group, the proportion was 55% for sympathetic participation, and 45% for parasympathetic modulation. This observation is consistent with LF/HF ratio, which is significantly decreased in the MCT+DIZE group compared to MCT alone group but not from controls (table 2).

Table 2.

Spectral and symbolic analysis results

| Spectral Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | MCT | MCT+DIZE | P | |

| HRV (ms2) | 108±47 | 12±8.86a | 40±14 | 0.000 |

| LFa (ms2) | 36±26 | 6.1±5.04a | 6.2±5.3a | 0.02 |

| HFa (ms2) | 59±29 | 4.3±3.1a | 30±16 | 0.001 |

| LFnu | 38±17 | 55±15 | 19±20b | 0.009 |

| HFnu | 62±17 | 45±15 | 81±20b | 0.009 |

| LF/HFratio | 0.74±0.62 | 1.45±0.78 | 0.34±0.49b | 0.01 |

| Symbolic Analysis (%) | ||||

| 0V pattern | 5.66±2.54 | 19±14 | 4.06±3.51a | 0.02 |

| 1V pattern | 40±8.86 | 37±8.45 | 27±13 | 0.172 |

| 2LV pattern | 11±2.78 | 7.16±6.45 | 12±7.92 | 0.130 |

| 2UV pattern | 43±8.75 | 37±5.02 | 56±15 | 0.054 |

CO= control rats, (n=7); MCT= rats treated with monocrotaline, (n=6); MCT+DIZE= rats treated with monocrotaline + Diminazene Aceturate, (n=6). HRV=Heart rate variability; LF= Low frequency component; HF= High frequency component; a= absolute; nu= normalized; Data represent means ± standard deviation. A non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to detect differences between groups; Data represent means ± standard deviation P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

vs control;

vs MCT

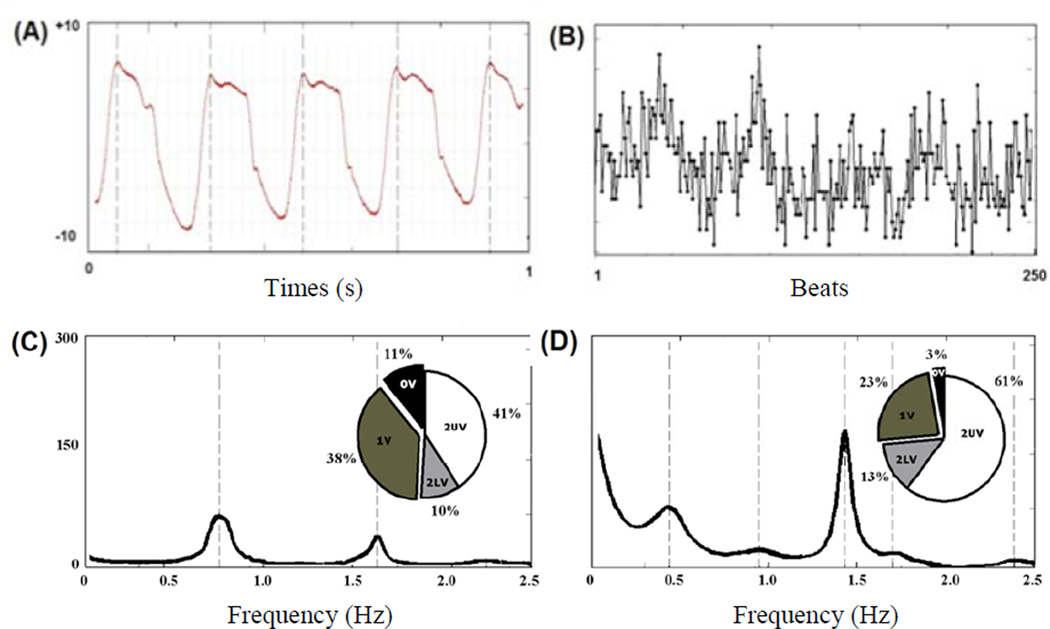

Symbolic analysis also showed that MCT induced an increase in 0V pattern (%), an indication of increased percentage of sympathetic modulation, compared to MCT+DIZE (table 2 and Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

An example of symbolic analysis of pulse interval (PI) series. The column shows the power spectrum of the time series: the frequency, expressed in Hz, is reported on the x-axis, while the power spectral density of PI series, expressed in ms2, is reported on the y-axis. The data expressed in the pie-chart represent the symbolic pattern distribution of the time series: all patterns are divided into the four families of patterns, i.e., 0V, 1V, 2LV, 2UV and the percentages of occurrence of the four families are shown. The upper panel shows an example of raw data obtained by intra-ventricular measurements (A) and a pulse interval series constructed from peak detection (B). On the lower panel are MCT treated animal (C) and MCT+DIZE (D) treated rats.

Collectively, symbolic and spectral analysis indicated that DIZE improved the autonomic modulation to the heart.

4. Discussion

The most significant observation of this study is that chronic treatment with DIZE improves the ANS modulation in the MCT-model of PH. DIZE increased the cardiac parasympathetic and decreased the sympathetic modulation, thus reversing the imbalance in the ANS modulation elicited by the pulmonary hypertensive state.

Our current findings agree with the published data showing that MCT treatment increases the cardiac sympathetic system participation (Fauchier et al., 2006; Goncalves et al.; Ishikawa et al., 2009). Moreover, activation of the sympathetic nervous system has been correlated with PH severity (Wensel et al., 2009) and development of right ventricle hypertrophy in humans (Ciarka et al., 2007; Dimopoulos et al., 2009; Folino et al., 2003; Velez-Roa et al., 2004; Wensel et al., 2009).

Our results are consistent with the previous reports involving animal models (Fauchier et al., 2006; Goncalves et al.) and clinical subjects (Dimopoulos et al., 2009; Fauchier et al., 2004; Fauchier et al., 2006; Folino et al., 2003; Rosas-Peralta et al., 2006; Wensel et al., 2009) whereupon, a decrease in the spectral power of HRV was observed with pulmonary hypertension.

In the current study, the MCT alone group showed a significant decrease in the spectral power of HRV, LFa and HFa as compared to the control group. The reduction in sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation observed in the MCT-treated rats has also been reported in pulmonary hypertensive patients (Fauchier et al., 2004). Similar to our findings in the MCT group, it has been shown in the literature that PH provokes a significant reduction in both LFa and HFa spectral power in animals (Fauchier et al., 2004) and subjects (Wensel et al., 2009).

The decrease in total power of HRV, seen in MCT group, indicates impairment in the ability of HR to blunt the increase in arterial blood pressure. On the other hand, there was an increase in parassympathetic and a decrease in sympathetic modulation to the heart in the MCT+DIZE group versus MCT alone. This conclusion is also based on the significant improvement in LF/HF ratio, seen after DIZE treatment. Likewise, similar findings have been reported in PH patients with an increase in LF versus HF spectral power ratio (LF/HF ratio) (Rosas-Peralta et al., 2006). The MCT+DIZE group showed a relative decrease in sympathetic modulation, as demonstrated by LFnu, and a corresponding increase in the parasympathetic modulation, as indicated by HFnu, compared with MCT rats. These findings strongly indicate that DIZE treatment alters the autonomic balance in favor of parasympathetic modulation in the MCT-induced PH.

Studies have reported that DIZE evoked either a decrease (Milner et al., 1997) or no change (Joubert et al., 2003) in arterial blood pressure. A possible explanation for this reduction in arterial blood pressure was put forward by Wien et al. (1943) who postulated that DIZE might induce parasympathetic modulation, by inhibiting acetyl-cholinesterase, an enzyme responsible for degrading the key parasympathetic mediator, acetylcholine (Wien, 1943). This might be the case since it has been reported that large doses of DIZE, when administered to animals, induces diarrhea and vomiting (Milner et al., 1997; Naude et al., 1970), classic symptoms of parasympathetic activation. However, contradicting this hypothesis were the findings of Milner et al., who demonstrated in dogs that DIZE did not change the concentration of acetyl-cholinesterase either in the plasma or red blood cells (Milner et al., 1997).

We believe that circulating acetyl-cholinesterase concentration may not reflect the parasympathetic nervous system modulation. As with the circulating levels of catecholamines in PH, which could be increased (Nagaya et al., 2000) or be within normal limits (Richards et al., 1990), the acetylcholinesterase levels may as well vary in circulation. Furthermore, another hypothesis could be that the parasympathetic system modulates the sympathetic nervous system activity centrally.

One of the limitations of our study is that all rats were under ketamine and xylazine anesthesia, which probably explains why our results show lower HR than in conscious Sprague Dawley rats. On the other hand, all groups were under anesthesia during the data collection, indicating that the differences found between the groups were not due to the procedure.

The exact mechanism by which DIZE acts remains to be determined. We had previously demonstrated that ACE2 activation can be a therapeutically relevant approach for treating and controlling PH (Ferreira et al., 2009). But, whether the beneficial effects of DIZE on autonomic function and right ventricle pressure in PH are due to ACE2 activation and/or to acetyl-cholinesterase inhibition are still important questions that need to be addressed. On the other hand, it is evident from our study that parasympathetic modulation, at least in part, is responsible for the beneficial effects against MCT-induced PH. We did provide evidences that DIZE treatment of PH rats alters the autonomic balance in favor of parasympathetic modulation.

It is very well established that for every mmHg that arterial blood pressure falls there is a proportional reduction in the risk for cardiovascular events. Similarly to arterial blood pressure, the HRV decrease may not always be significant, but its impact on patient survival may be very relevant.

It is also well recognized that under chronic left heart failure, the sympathetic activity is increased and blockade of the same improves symptoms, cardiac function and the prognosis of patients (Swedberg et al., 2005). Future studies need to focus on the function of ANS in PH. Measurement of cardiac autonomic function and its treatment may play an important role in prognostic risk stratification and effectively determine the clinical outcomes in patients suffering from PH.

5. Conclusion

Despite the efforts of the scientific community, the survival rate of patients with PH remains poor and unacceptable. Thus, a drug that improves the ANS balance and decreases the ventricle pressure, certainly will postpone the transition from compensated hypertrophy to maladaptive remodeling and dilatation, improving survival in PH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There is no conflict of interest

References

- Bradford CN, Ely DR, Raizada MK. Targeting the vasoprotective axis of the rennin-angiotensin system: a novel strategic approach to pulmonary hypertensive therapy. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:212–219. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0122-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali KR, Casali AG, Montano N, Irigoyen MC, Macagnan F, Guzzetti S, Porta A. Multiple testing strategy for the detection of temporal irreversibility in stationary time series. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2008;77:066204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.77.066204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarka A, Vachiery JL, Houssiere A, Gujic M, Stoupel E, Velez-Roa S, Naeije R, van de Borne P. Atrial septostomy decreases sympathetic overactivity in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2007;131:1831–1837. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabire H, Mestivier D, Jarnet J, Safar ME, Chau NP. Quantification of sympathetic and parasympathetic tones by nonlinear indexes in normotensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1290–H1297. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias da Silva VJ, Montano N, Salgado HC, Fazan Junior R. Effects of long-term angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on cardiovascular variability in aging rats. Auton Neurosci. 2006;124:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos S, Anastasiou-Nana M, Katsaros F, Papazachou O, Tzanis G, Gerovasili V, Pozios H, Roussos C, Nanas J, Nanas S. Impairment of autonomic nervous system activity in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a case control study. J Card Fail. 2009;15:882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauchier L, Babuty D, Melin A, Bonnet P, Cosnay P, Paul Fauchier J. Heart rate variability in severe right or left heart failure: the role of pulmonary hypertension and resistances. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauchier L, Melin A, Eder V, Antier D, Bonnet P. Heart rate variability in rats with chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 2006;55:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ancard.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira AJ, Shenoy V, Yamazato Y, Sriramula S, Francis J, Yuan L, Castellano RK, Ostrov DA, Oh SP, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK. Evidence for angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 as a therapeutic target for the prevention of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(11):1048–1054. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1678OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folino AF, Bobbo F, Schiraldi C, Tona F, Romano S, Buja G, Bellotto F. Ventricular arrhythmias and autonomic profile in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Lung. 2003;181:321–328. doi: 10.1007/s00408-003-1034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillman MW, Kannel WB, Belanger A, D'Agostino RB. Influence of heart rate on mortality among persons with hypertension: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1993;125:1148–1154. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90128-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjymishka A, Kulemina LV, Shenoy V, Kayovich MJ, Ostrov DA, Raizada MK. Diminazene aceturate is an ACE2 activator and a novel antihypertensive drug. FASEB J. 2010:1032.3. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves H, Henriques-Coelho T, Bernardes J, Rocha AP, Brandao-Nogueira A, Leite-Moreira A. Analysis of heart rate variability in a rat model of induced pulmonary hypertension. Med Eng Phys. 32:746–752. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzetti S, Borroni E, Garbelli PE, Ceriani E, Della Bella P, Montano N, Cogliati C, Somers VK, Malliani A, Porta A. Symbolic dynamics of heart rate variability: a probe to investigate cardiac autonomic modulation. Circulation. 2005;112:465–470. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.518449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessel MH, Steendijk P, den Adel B, Schutte CI, van der Laarse A. Characterization of right ventricular function after monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in the intact rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2424–H2430. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00369.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Sato N, Asai K, Takano T, Mizuno K. Effects of a pure alpha/beta-adrenergic receptor blocker on monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension with right ventricular hypertrophy in rats. Circ J. 2009;73:2337–2341. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert KE, Kettner F, Lobetti RG, Miller DM. The effects of diminazene aceturate on systemic blood pressure in clinically healthy adult dogs. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2003;74:69–71. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v74i3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecca AP, Regenhardt RW, O'Connor TE, Joseph JP, Raizada MK, Katovich MJ, Sumners C. Cerebroprotection by angiotensin-(1–7) in endothelin-1-induced ischaemic stroke. Exp Physiol. 96:1084–1096. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner RJ, Reyers F, Taylor JH, van den Berg JS. The effect of diminazene aceturate on cholinesterase activity in dogs with canine babesiosis. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1997;68:111–113. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v68i4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar J, Rosenthal JE, Weiss JS, Somberg JC. QT interval dispersion in healthy subjects and survivors of sudden cardiac death: circadian variation in a twenty-four-hour assessment. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:1190–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montano N, Ruscone TG, Porta A, Lombardi F, Pagani M, Malliani A. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability to assess the changes in sympathovagal balance during graded orthostatic tilt. Circulation. 1994;90:1826–1831. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murasato Y, Hirakawa H, Harada Y, Nakamura T, Hayashida Y. Effects of systemic hypoxia on R-R interval and blood pressure variabilities in conscious rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H797–H804. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.3.H797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaya N, Nishikimi T, Uematsu M, Satoh T, Kyotani S, Sakamaki F, Kakishita M, Fukushima K, Okano Y, Nakanishi N, Miyatake K, Kangawa K. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide as a prognostic indicator in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2000;102:865–870. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naude TW, Basson PA, Pienaar JG. Experimental diamidine poisoning due to commonly used babecides. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1970;37:173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrofsky JS, Lohman E, Lohman T. A device to evaluate motor and autonomic impairment. Med Eng Phys. 2009;31:705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta A, Casali KR, Casali AG, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Tobaldini E, Montano N, Lange S, Geue D, Cysarz D, Van Leeuwen P. Temporal asymmetries of short-term heart period variability are linked to autonomic regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R550–R557. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00129.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta A, Faes L, Mase M, D'Addio G, Pinna GD, Maestri R, Montano N, Furlan R, Guzzetti S, Nollo G, Malliani A. An integrated approach based on uniform quantization for the evaluation of complexity of short-term heart period variability: Application to 24 h Holter recordings in healthy and heart failure humans. Chaos. 2007;17:015117. doi: 10.1063/1.2404630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta A, Montano N, Furlan R, Cogliati C, Guzzetti S, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Malliani A, Chang HS, Staras K, Gilbey MP. Automatic classification of interference patterns in driven event series: application to single sympathetic neuron discharge forced by mechanical ventilation. Biol Cybern. 2004;91:258–273. doi: 10.1007/s00422-004-0513-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards AM, Ikram H, Crozier IG, Nicholls MG, Jans S. Ambulatory pulmonary arterial pressure in primary pulmonary hypertension: variability, relation to systemic arterial pressure, and plasma catecholamines. Br Heart J. 1990;63:103–108. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BF, Epstein SE, Beiser GD, Braunwald E. Control of heart rate by the autonomic nervous system. Studies in man on the interrelation between baroreceptor mechanisms and exercise. Circ Res. 1966;19:400–411. doi: 10.1161/01.res.19.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Peralta M, Sandoval-Zarate J, Attie F, Pulido T, Santos E, Granados NZ, Miranda T, Escobar V. Clinical implications and prognostic significance of the study on the circadian variation of heart rate variability in patients with severe pulmonary hypertension. Gac Med Mex. 2006;142:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal SN, Ono K. Derangement of autonomic nerve control in rat with right ventricular failure. Pathophysiology. 2002;8:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4680(02)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy V, Gjymishka A, Yagna J, Qi Y, Afzal A, Rigatto K, Ferreira AJ, Fraga-Silva RA, Kearns P, Yellowlees Douglas J, Agarwal D, Mubarak KK, Bradford C, Kennedy WR, Jun JY, Rathinasabapathy A, Bruce E, Gupta D, Cardounel AJ, Mocco J, Patel JM, Francis J, Grant MB, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK. Diminazene Attenuates Pulmonary Hypertension and Improves Angiogenic Progenitor Cell Functions in Experimental Models. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0880OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares PP, da Nobrega AC, Ushizima MR, Irigoyen MC. Cholinergic stimulation with pyridostigmine increases heart rate variability and baroreflex sensitivity in rats. Auton Neurosci. 2004;113:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedberg K, Cleland J, Dargie H, Drexler H, Follath F, Komajda M, Tavazzi L, Smiseth OA, Gavazzi A, Haverich A, Hoes A, Jaarsma T, Korewicki J, Levy S, Linde C, Lopez-Sendon JL, Nieminen MS, Pierard L, Remme WJ. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: executive summary (update 2005): The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1115–1140. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez-Roa S, Ciarka A, Najem B, Vachiery JL, Naeije R, van de Borne P. Increased sympathetic nerve activity in pulmonary artery hypertension. Circulation. 2004;110:1308–1312. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140724.90898.D3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waki H, Katahira K, Polson JW, Kasparov S, Murphy D, Paton JF. Automation of analysis of cardiovascular autonomic function from chronic measurements of arterial pressure in conscious rats. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:201–213. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensel R, Jilek C, Dorr M, Francis DP, Stadler H, Lange T, Blumberg F, Opitz C, Pfeifer M, Ewert R. Impaired cardiac autonomic control relates to disease severity in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:895–901. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00145708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werchan PM, Summer WR, Gerdes AM, McDonough KH. Right ventricular performance after monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H1328–H1336. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.5.H1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]