Abstract

Background

THAP1 was recently identified as the gene causing DYT6 primary dystonia; a founder mutation was detected in Amish–Mennonite families and a different mutation identified in an additional family. To determine the role of this gene more broadly, we screened for mutations in early-onset primary dystonia families with diverse ancestries.

Methods

We identified 36 non-DYT1 multiplex families in which at least one individual had non-focal involvement and onset <22 years. All THAP1 coding exons were sequenced. Clinical features of those with DYT6 mutations were compared to mutation negative individuals and genotype-phenotype differences assessed.

Findings

Nine of 36 families (25%) harbored mutations and most were of German, Irish or Italian ancestry. One had the Amish-Mennonite founder mutation, while the remaining 8 families each harbored unique truncating or missense mutations. Clinical features in families with mutations conformed to the previously described DYT6 phenotype; age–onset, however, extended to 49 years. Compared to non-carriers, mutation carriers were younger at onset; their dystonia was more likely to begin in brachial, and not cervical, muscles and was more likely to become generalized including speech involvement. Genotype–phenotype differences were not found.

Interpretation

THAP1 mutations underlie a substantial proportion of early-onset primary dystonia in non-DYT1 families of differing European ancestry. Characteristic clinical features include involvement of both limb and cranial muscles and speech is often affected.

Search terms: genetics, dystonia, movement disorders, THAP1

Introduction

The clinical spectrum of primary dystonia is wide, ranging from childhood-onset disease that often generalizes to adult onset localized contractions commonly affecting cervical or cranial muscles. From its earliest descriptions over 100 years ago genetic etiologies were suspected, especially in the subset with early onset 1. Over the last twenty years, five loci (DYT1, 6, 7, 13, and 17) have been mapped using linkage in families with primary, pure forms of dystonia; genes for only two, DYT1 and DYT6, have been identified, DYT6 very recently 2,3,4. DYT1 is a major cause of early limb onset disease 5,6. DYT6, like other mapped loci 7,8, was considered to be of limited import, restricted to Amish-Mennonite families all sharing a founder haplotype 9,10. With identification of the gene its role can now be directly assessed.

In identifying the gene for DYT6, THAP1, we found two different heterozygous mutations in five families 4. Four of the five families shared the same 5bp insertion/3bp deletion, haplotype, and Amish-Mennonite ancestry, indicating a founder mutation. Further, all 5 families with THAP1 mutations shared similar clinical features, a phenotype that was described as “mixed” 4,9,10; this term was chosen because most, but not all, affected family members expressed clinical features that were intermediate (or mixed) yet distinct from 1) early-onset limb predominant dystonia associated with DYT1 and 2) late–onset localized cervical and cranial dystonia, which constitutes the majority of primary dystonia. Like DYT1, DYT6 symptoms tended to begin early and dystonia usually spread to involve multiple body regions. However, compared to DYT1, DYT6 was more likely to begin in cervical or cranial muscles, and when it started in the limbs was much more likely to spread to cranial muscles; on the other hand, disabling leg and gait abnormalities were less common in DYT6 compared to DYT1.

In identifying THAP1, aside from finding the Amish-Mennonite founder mutation, we also discovered a unique missense mutation in one clinically similar family. This family had European but not Amish-Mennonite ancestry, suggesting that THAP1 may be a cause of dystonia outside the Amish-Mennonite population. We now report DYT6 screening of DYT1 negative families not ascertained because of Amish-Mennonite ancestry, and having early onset non-focal primary dystonia, a phenotype consistent with DYT6.

Methods

Participants

Participating families were ascertained from a database that includes subjects recruited from the Movement Disorders Center at Beth Israel Medical Center (New York), Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center (New York), and Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and through research advertisements. We identified 37 multiplex families in which at least one family member had childhood or adolescent-onset (beginning before age 22 years) of dystonic symptoms and muscle involvement that was segmental, multifocal or generalized. These families were not recruited because of Amish-Mennonite ancestry, and in all families we endeavored to examine living family members reported to be affected or screening positive for dystonic symptoms. For all affected individuals there were no clinical signs or laboratory findings to suggest secondary dystonia, and mutation screening for the DYT1 GAG deletion was negative. One of these 37 families (family S) was included in our report identifying THAP1 4, leaving 36 families newly screened for mutations. Family S, along with the four Amish-Mennonite families (M, C, R and W) also described in the report identifying THAP1, are included here as a separate group to more fully describe the phenotype associated with THAP1 mutations and for phenotype-genotype analysis.

There were a total of 104 affected family members in these 36 newly screened families with clinical information and DNA available for analyses. Of these 104 affected family members, 86 had in person and videotaped exams, and an additional 4 had video examinations and records available. The remaining 14 individuals were evaluated by a neurologist specializing in movement disorders, and information was derived from medical records and telephone interviews. Interviews, record reviews, and examinations followed published protocols to ensure the diagnosis and distribution of sites affected with definite primary dystonia 11. Final clinical status blinded to DYT6 genotype and using all available clinical information was determined by two of the authors (SBB and RSP). Age and site at onset were determined by self report and review of medical records.

All subjects gave informed consent before their participation in this study, which was approved by the Beth Israel Medical Center, Columbia–Presbyterian Medical Center, and Mount Sinai School of Medicine review boards.

Molecular Analysis

Blood samples were collected from participants and DNA was extracted using standard methods. Screening for the three base pair deletion in the DYT1 locus was performed as previously described 12. For THAP1, we initially screened the index case from each of the 36 families. The three coding exons of the gene were fully sequenced including 5′ and 3′ UTRs. In order to look for splice site mutations, at least 50 bp of upstream and downstream intronic sequence surrounding each exon was also sequenced. Standard PCR amplification was performed using primers and conditions available upon request, except for THAP1 Exon 1, for which AccuPrime™ GC-rich DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used in the amplification. Standard dideoxy cycle sequencing was performed on amplified fragments. In 277 Human Random DNA control samples representing UK healthy Caucasian blood donors (Sigma-Aldrich), the 5′UTR and entire coding region of THAP1 including splice sites was sequenced. The Amish-Mennonite haplotype was determined as previously described 4.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical features of all affected individuals from families with a DYT6 mutation were compared to individuals from mutation negative families. Since more than one member of a family was included, we used generalized estimating equation (GEE) models (for dichotomous variables) and random effects model within generalized least squares regression (for continuous or ordinal variables) to control for the nonindependence of individuals within the same family. These models were used to compare age at onset, site onset, final distribution, sex and final sites involved using STATA8 software (Stata, TX). We also assessed for differences between subjects with THAP1 deletions or nonsense mutations, all producing truncations, compared to THAP1 missense mutations.

Role of Funding Sources

The sponsors of this study had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

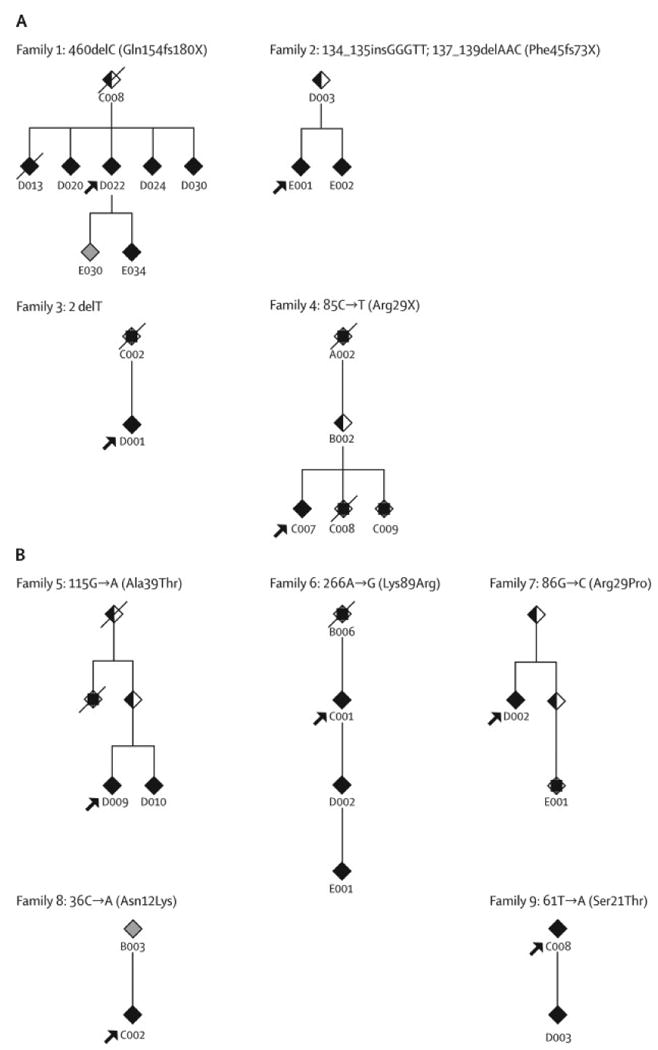

Of the 36 families, 9 (25%) harbored mutations; this group includes 19/104 (18%) affected individuals. The pedigrees and mutations in these families are shown in Figure 1. Of note, in families 1 and 8, a family member considered affected did not have the family THAP1 mutation. Both of these individuals were men and had symptomatic brachial dystonia for 20 years with writing only (writer's cramp), beginning at ages 6 and 34. They were considered phenocopies and not included in either genetic group of families.

Figure 1.

Partial pedigrees showing affected individuals and intervening relatives. Individuals D013, D020, and D022 from Family 1 were reported in Kramer et al 1994 21. Each family number is followed by the corresponding mutation and protein designation. Truncating mutations are shown in panel A; missense mutations in panel B. Solid symbols denote affected individuals included in our analysis; half filled symbols denote asymptomatic obligate carriers; a square inside a symbol denotes someone with a clear history of dystonia whose records/exam we were unable to obtain.

Eight of the nine families had unique mutations (Figures 1 and 2). Seven of these 8 mutations occurred in the DNA binding domain and include: one nonsense mutation, five missense mutations, each resulting in the substitution of a residue that is highly conserved across species (Figure 2b), and one small deletion mutation that removes the start codon. The eighth mutation is a deletion of a single basepair which results in truncation of the protein, leaving the DNA binding domain intact, but disrupting the nuclear localization signal. These mutations were not observed in over 500 chromosomes from European Caucasians.

Figure 2.

A. Schematic representation of the THAP1 protein depicts the THAP domain (purple), low-complexity proline rich region (blue), coiled-coil domain (violet) and nuclear localization signal (dark purple). The identified mutations are shown to scale, with the substitution (missense) mutations on the top and the truncating (nonsense and frameshift) mutations on the bottom. “p.?” represents the deletion of “G” in the “ATG” codon of the first Methionine of the protein and reflects the fact that there is no experimental evidence on the expression of the protein product of this mutant. Previously identified mutations are indicated by “^” 4. Mutation nomenclature was taken from den Dunnen and Antonarakis (2001) 22 with numbering beginning at the start ATG. B. Alignment of the THAP domain sequences of THAP1 orthologs. Protein sequences of the THAP1 orthologs were withdrawn from NCBI Gene database and aligned using ClustalW. The alignment corresponding to the THAP domain is shown. The residues encoding the missense mutations and first Methionine are highlighted in purple.

The ninth family had the same insertion deletion mutation and haplotype identified in our Amish-Mennonite kindreds. This family was not aware of Amish-Mennonite background and had mixed European ancestry. Ancestral countries of origin in the remaining eight families included: Ireland (3), Italy (2), Germany (2) and Russia (1). None described Jewish ancestors. The 27 families without identified mutations included 85 individuals with dystonia. Self reported ancestry included mixed European (13), Ashkenazi Jewish (6), Irish (3), African (2), Italian (2), and French Canadian (1).

Clinical features in individuals with THAP1 mutations

Clinical features of those with identified mutations are summarized in the Table. Among the newly described mutation positive families, most individuals had childhood or adolescent onset; while 3/19 began in adulthood (> 21 years) at ages 25, 29 and 49. First symptoms often involved an arm, although 5/15 with arm onset reported simultaneous onset in other regions including the other arm in three, a leg in one, and the other arm, neck, and tongue in another. Dystonia spread widely in most, with 12/19 having generalized or multifocal distributions; even though one or both legs were involved in all, none required a wheelchair and most had only mild or moderate disability related to gait. Further, all 12 also had cranial muscle involvement including face, tongue and larynx. When considering the group overall including the previously reported mutation positive group, cranial muscles were involved in 77% and speech was affected in 67%. Although most affected individuals had widespread dystonia affecting limbs, neck and cranial muscles, 5 had more restricted disease, 4 with writer's cramp and 1 with spasmodic dysphonia.

Table. Comparison of THAP1 Mutation Positive and Negative Groups.

| Clinical Features | Mutation Positive | Mutation Negative (Families=27, n=85) | p Value (combined positive vs. negative) a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newly Reported (Families=9, n=19) | Previously Reported (Families=5, n=29) | Combined (Families=14, n=48) | |||

| Female (%) | 63 | 59 | 60 | 67 | NS |

| Median Age Onset | 12.0 (2-49) | 13.5 (5-38)* | 13.0 (2-49)* | 20.0 (1-59)**** | 0.002 |

| Median Age Exam (range) | 39.0 (14-58) | 43.0 (10-79) | 42.5 (10-79) | 47.0 (4-78) | NS |

| Duration of Dystonia (range) | 31.0 (0-47) | 17.5 (2-66)* | 20.0 (0-66)* | 20.0 (0-72)**** | NS |

| Site Onset % (n) | Arm: 79% (15) | Arm: 45% (13) | Arm: 58% (28) | Arm: 19% (16) | Arm: <0.001 |

| Leg: 5% (1) | Leg: 14% (4) | Leg: 10% (5) | Leg: 22% (19) | Leg: 0.113 | |

| Cranial: 21% (4) | Cranial: 34% (10) | Cranial: 29% (14) | Cranial: 20% (17) | Cranial: 0.233 | |

| Face: 5% (1) | Face: 14% (4) | Face: 10% (5) | Face: 11% (9); | Cervical: <0.001 | |

| Jaw/tongue: 11% (2) | Jaw/tongue: 10% (3) | Jaw/tongue: 10% (5) | Jaw/tongue: 2% (2) | ||

| Larynx: 5% (1) | Larynx: 10% (3) | Larynx: 8% (4) | Larynx: 9% (8) | ||

| Cervical: 11% (2) | Cervical: 21% (6) | Cervical: 17% (8) | Cervical: 60% (51) | ||

| Sites At Exam % (n) | Arm: 100% (19) | Arm: 86% (25) | Arm: 92% (44) | Arm: 51% (43) | Arm: <0.001 |

| Leg: 63% (12) | Leg: 52% (15) | Leg: 56% (27) | Leg: 32% (27) | Leg: 0.028 | |

| Cranial: 79% (15) | Cranial: 76% (22) | Cranial: 77% (37) | Cranial: 51% (43) | Cranial: 0.001 | |

| Face: 58% (11) | Face: 55% (16) | Face: 56% (27) | Face: 31% (26) | ||

| Jaw/tongue: 37% (7) | Jaw/tongue: 45% (13) | Jaw/tongue: 42% (20) | Jaw/tongue: 15% (13) | ||

| Larynx: 21% (4) | Larynx: 41% (12) | Larynx: 33% (16) | Larynx: 21% (18) | ||

| Cervical: 63% (12) | Cervical: 59% (17) | Cervical: 60% (29) | Cervical: 71% (60) | Cervical: 0.706 | |

| Speech: 63% (12) | Speech: 69% (20) | Speech: 67% (32) | Speech: 33% (28) | Speech: 0.001 | |

| Distribution % (n) | Focal: 11% (2) | Focal: 10% (3) | Focal: 10% (5) | Focal: 36% (31) | 0.002 b |

| Segmental: 26% (5) | Segmental: 38% (11) | Segmental: 33% (16) | Segmental: 34% (29) | ||

| Multifocal: 5% (1) | Multifocal: 14% (4) | Multifocal: 10% (5) | Multifocal: 7% (6) | ||

| Generalized: 58% (11) | Generalized: 38% (11) | Generalized: 46% (22) | Generalized: 22% (19) | ||

The number of stars indicates the number of individuals in that group whose age onset could not be determined.

Analyses adjusted for within family correlations using generalized estimating equations (categorical) and random effects GLS (continuous or ordinal)

For each one-unit increase in distribution severity (focal, segmental, multifocal, generalized)

The oldest age of onset in the newly identified group was greater than previously described for DYT6 (49 years vs. 38), however, the median age of onset was not different between these groups. Clinical features were similar otherwise except that the arm was more commonly the first site affected in the newly identified group.

Clinical features in those without THAP1 mutations and comparison to those with mutations

Affected individuals from families without identified mutations had a higher age at onset compared to the mutation positive group (Table), despite the narrow inclusion criteria requiring at least one family member with early-onset non-focal dystonia. Their dystonia commonly began in the cervical muscles, unlike those with THAP1 mutations (60% vs. 17%), whereas the arm was first affected in only 19% of negative individuals compared to 58% in those with mutations. Similarly there was a difference in the frequency of an arm ever being involved (51% vs. 92%). Compared to the mutation positive group speech was less frequently affected, and there was less extensive muscle involvement with a smaller proportion progressing to a generalized distribution (22% vs. 46%). Conversely a higher proportion, 36%, remained focal, with the neck being the most common focal site. Despite these differences, there were several mutation negative families that displayed clinical features similar to those observed in mutation positive families, including early onset with spread to multiple regions and prominent cranial involvement affecting speech.

Genotype / Phenotype

To examine the relationship between genotype and clinical expression, we divided the 14 THAP1 positive families into two groups: those with truncating mutations (8 families including the original Amish Mennonite kindred) and those with missense mutations (6 families). We identified no differences in age onset, sites of onset or final distribution (data not shown).

Discussion

We found that mutations in the DYT6 gene, THAP1, underlie a significant proportion of familial early-onset primary dystonia; 25% of our 36 families harbored mutations. Of the nine families with mutations, one shared the 5bp insertion/3bp deletion and haplotype identified in the Amish-Mennonite kindreds in which DYT6 was initially mapped. The remaining eight families each had unique mutations involving all 3 exons and also represented a diversity of ancestries, although all had European non-Jewish origins. There were no phenotype differences corresponding to THAP1 mutation type. However, all identified mutations affected the DNA binding domain or removed the nuclear localization signal, pointing to this region of the protein as being functionally important (Figure 2). Beyond its role in binding DNA, this domain is also essential for the pro-apoptotic function associated with this protein 13. THAP1 is a nuclear proapoptotic factor that interacts with prostate-apoptosis-response-4 (Par-4) and co-localizes with it to PML nuclear bodies 13.

In our report identifying THAP1 4, we proposed a role for this gene outside the Amish-Mennonite population based on a single German family that was found to have a different missense mutation. That family, like the Amish-Mennonite kindred, had a “mixed” phenotype, and so our first step in elucidating the role of THAP1 was to screen families with a consistent phenotype, i.e. containing at least one member with early onset and non-focal dystonia. Despite our clinical restrictions in defining the group of families for screening, we identified differences between those with and without mutations; mutation positive cases have an earlier onset with a greater tendency to generalize and more commonly involve brachial, facial and oromandibular muscles. These differences are consistent with the characteristic “mixed” phenotype of DYT6 previously reported 9,10.

Because we specifically excluded individuals with the DYT1 GAG deletion, we did not fully depict the range of early onset dystonia and distinct clinical features associated with THAP1 in this population as they compare to DYT1. That is, although many with THAP1 mutations had onset in childhood and 90% began before age 30, more than 30% had onset after age 18 years, a larger proportion than reported for DYT1 5,14. Also, compared to DYT1, leg–onset in DYT6 was less common 5. Perhaps most characteristic of DYT6, distinguishing it from DYT1, was the proportion of individuals with onset (29%) or subsequent involvement (77%) of cranial muscles 12,15. In most of these individuals this produced disabling dysarthria or dysphonia. Finally, unlike DYT1, there was a preponderance of women. An excess of affected women in DYT6 families has been noted previously 10 and remains unexplained. DYT6 lifetime penetrance is estimated to be 57-60% with no sex differences identified 10; however, the number of male gene carriers studied was small. The families reported here also contained unaffected mutation carriers, supporting reduced penetrance (Figure 1); future systematic assessment of DYT6 families should help resolve whether, indeed, sex differences in penetrance can be demonstrated.

Although we were able to confirm an overall clinically distinct DYT6 phenotype there are several caveats to our study. One important caveat is the recognition that DYT6 expression is broad and overlaps other non-DYT6 dystonia subtypes. This applies to other dystonia subgroups that have prominent speech involvement (e.g., DYT4, DYT17, DYT12) and the common phenotype of brachial and bi-brachial dystonia. Indeed, we identified two family members within mutation positive families with writer's cramp who did not harbor the family mutation. Writer's cramp represents a particularly problematic phenotype for genetic studies 16,17, and caution in classifying individuals as “affected” for gene mapping is reinforced by our study. Also, mutation analysis was restricted to sequence variants within the regions screened. Screening for other genetic changes including exonic deletions/multiplications and variants in intronic regions may underlie additional cases and requires further study. Finally, we only assessed a population consistent with the DYT6 phenotype as initially described; other dystonia populations, especially sporadic and late-onset focal dystonias, remain to be tested.

Future studies should help clarify the role of THAP1 mutations in dystonia and their pathogenic effects. Based on identified mutations, THAP1 DNA binding and pro-apoptotic functions are implicated; transcription factors and apoptosis have not been previously associated with primary dystonia, although the gene causing X-linked dystonia parkinsonism (XDP), encodes a transcription factor, TAF118. Of further interest is the potential diverging and shared effects of THAP1 and torsinA, the DYT1 gene product. Mutations in these genes produce clinical phenotypes with relatively subtle differences. Additionally, PET and MRI studies have demonstrated that DYT6 “manifesting” gene carriers share metabolic 19 and anatomic 20 abnormalities with DYT1, yet metabolic differences between DYT1 and DYT6 genotypes were also demonstrated. This suggests that torsinA and THAP1 have distinct pathogenic origins that may converge on key brain targets to produce shared motor expression. Understanding the function of THAP1 and probing potential interactions with torsinA should provide novel mechanistic clues and targets for therapy.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all patients and family members who participated in this study. We thank Paul Greene*, Anthony Lang*, Mitchell Brin*, Michael Hutchinson*, Timothy Lynch*, Sean O'Riordan*, Richard Walsh, Fabio Danisi*, Ann Hunt, Neng Huang, Rowena Desailly-Chanson, Kyra Blatt, Edward Chai, Sylvain Chouinard, Patricia Kavanagh, Stanley Fahn, Gizelle Petzinger, John Hammerstad, Robert Burke, Cordelia Schwarz, Vicki Shanker for help with examination of the families, Jeannie Soto-Valencia, Kristina Habermann, Deborah de Leon and Carol Moskowitz for organizing and coordinating family visits, Natalia Lyons and Amber Buckley for technical help. We thank the physicians indicated with a * for referring families included in our analysis. This work was supported by research grants from the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation (LO, SBB, RSP), the Bachmann-Strauss Dystonia Parkinson Disease Foundation (SBB, LO), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS26636, LJO, DR & SBB; K23NS047256, RSP), and the Aaron Aronov Family Foundation (SBB and DR).

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: All of the authors contributed to the content and revision of the manuscript, table and figures. In addition, Dr. Susan Bressman is the Principal Investigator for the study. She wrote the manuscript and reviewed patient videotapes to confirm affected status. Deborah Raymond coordinated and participated in the collection of much of the data and worked on the statistical analysis. Dr. Tania Fuchs and Dr. Laurie Ozelius did the molecular analysis. Dr. Rachel Saunders-Pullman examined study subjects and reviewed videotapes on patients she did not examine. She also supervised statistical analyses on the study data. Dr. Gary Heiman performed additional statistical analyses.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Role of Funding Sources

The sponsors of this study had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- 1.Ozelius LJ, Bressman SB. DYT1 dystonia. In: Warner TT, Bressman SB, editors. Clinical Diagnosis and Management of Dystonia. London: Informa healthcare; 2007. pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bressman SB. Genetics of dystonia: an overview. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(3):S347–355. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(08)70029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chouery E, Kfoury J, Delaugue V, et al. A novel locus for autosomal recessive primary torsion dystonia (DYT17) maps to 20p11.22-q13.12. Neurogenetics. 2008;9:287–293. doi: 10.1007/s10048-008-0142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs T, Saunders-Pullman R, Raymond D, et al. Mutations in the THAP1 gene are responsible for DYT6 primary torsion dystonia. Nat Genet Epub. 2009 Feb 1; doi: 10.1038/ng.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bressman SB, Sabatti C, Raymond D, et al. The DYT1 phenotype and guidelines for diagnostic testing. Neurology. 2000;54:1746–1752. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.9.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gambarin M, Valente EM, Liberini P, et al. Atypical phenotypes and clinical variability in a large Italian family with DYT1-primary torsion dystonia. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1782–1784. doi: 10.1002/mds.21056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leube B, Rudnicki D, Ratzlaff T, Kessler KR, Benecke R, Auburger G. Idiopathic torsion dystonia: assignment of a gene to chromosome 18p in a German family with adult onset, autosomal dominant inheritance and purely focal distribution. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1673–1677. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valente EM, Bentivoglio AR, Cassetta E, et al. DYT13, a novel primary torsion dystonia locus, maps to chromosome 1p36. 13-36.32 in an Italian family with cranial-cervical or upper limb onset. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almasy L, et al. Idiopathic torsion dystonia linked to chromosome 8 in two Mennonite families. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:670–673. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunders-Pullman R, et al. Narrowing the DYT6 dystonia region and evidence for locus heterogeneity in the Amish-Mennonites. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:2098–2105. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bressman SB, de Leon D, Brin MF, et al. Idiopathic dystonia among Ashkenazi Jews: evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:612–620. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozelius LJ, et al. The early-onset torsion dystonia gene (DYT1) encodes an ATP-binding protein. Nat Genet. 1997;17:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roussigne M, Cayrol C, Clouaire T, Amalric F, Girard JP. THAP1 is a nuclear proapoptotic factor that links prostate-apoptosis-response-4 (Par-4) to PML nuclear bodies. Oncogene. 2003;22:2432–2442. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bressman SB, de Leon D, Kramer PL, et al. Dystonia in Ashkenazi Jews: clinical characterization of a founder mutation. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:771–777. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fasano A, Nardocci N, Elia AE, Zorzi G, Bentivoglio AR, Albanese A. Non-DYT1 early-onset primary torsion dystonia: comparison with DYT1 phenotype and review of the literature. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1411–1418. doi: 10.1002/mds.21000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer PL, et al. Rapid-onset dystonia-parkinsonism:linkage to chromosome 19q13. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:176–182. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199908)46:2<176::aid-ana6>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bressman SB, Raymond D, Wendt K, et al. Diagnostic criteria for dystonia in DYT1 families. Neurology. 2002;59:1780–1782. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000035630.12515.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makino S, Kaji R, Ando S. Reduced neuron-specific expression of the TAF1 gene is associated with X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:393–406. doi: 10.1086/512129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carbon M, Su S, Dhawan V, Raymond D, Bressman S, Eidelberg D. Regional metabolism in primary torsion dystonia: effects of penetrance and genotype. Neurology. 2004;62:1384–1390. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000120541.97467.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carbon M, Kingsley PB, Tang C, Bressman S, Eidelberg D. Microstructural white matter changes in primary torsion dystonia. Mov Disord. 2008;23:234–239. doi: 10.1002/mds.21806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer PL, Heiman GA, Gasser T, et al. The DYT1 gene on 9q34 is responsible for most cases of early limb-onset idiopathic torsion dystonia in non-Jews. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:468–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis E. Nomenclature for the description of human sequence variations. Hum Genet. 2001;109:121–124. doi: 10.1007/s004390100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]