Abstract

Background

Professional and patient groups have called for increased participation of patients’ informal support networks in chronic disease care, as a means to improve clinical care and self-management. Little is known about the current level of participation of family and friends in the physician visits of adults with chronic illnesses or how that participation affects the experience of patients and physicians.

Methods

Written survey of 439 functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure and 88 of their primary care physicians (PCPs). Patients were ineligible if they had a memory disorder, needed help with activities of daily living, or were undergoing cancer treatment.

Results

Non-professional friends or family (“companions”) regularly participated in PCP visits for nearly half (48%) of patients. In multivariable models, patients with low health literacy (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] 2.9, CI 1.4-5.7), more depressive symptoms (AOR 1.3, CI 1.1-1.6), and 4 or more comorbid illnesses (AOR 3.7, CI 1.3-10.5) were more likely to report companion participation. Patients reported that they were more likely to understand PCP advice (77%) and discuss difficult topics with the physician (44%) when companions participated in clinic visits. In multivariable models, companion participation was associated with greater patient satisfaction with their PCP (AOR 1.7, CI 1.1-2.7). While most PCPs perceived visit companions positively, 66% perceived one or more barriers to increasing companion participation, including increased physician burden (39%), inadequate physician training (27%), and patient privacy concerns (24%).

Conclusion

Patients’ companions represent an important source of potential support for the clinical care of functionally independent patients with diabetes or heart failure, particularly for patients vulnerable to worse outcomes. Companion participation in care was associated with positive patient and physician experiences. Physician concerns about companion participation are potentially addressable through existing training resources.

Introduction

Chronic diseases, such as diabetes and heart failure, cause significant morbidity in U.S. adults and place large demands on patients’ visits with their primary care physicians (PCPs).1, 2 PCPs need to review home monitoring and clinical test results, assess symptom trends, adjust medication regimens, monitor completion of recommended care processes, encourage healthy behavior changes, and provide emotional support. Effective patient-provider communication is crucial,3, 4 yet patients and physicians often understand each other poorly5, 6 and lack the information they both need to make important decisions about illness management.7

Family members and friends of these patients could potentially provide effective support for these complex clinical encounters. Family and friends of chronically ill adults often provide significant support for day-to-day self-management, through emotional support, direct assistance with tasks, and facilitation of healthy behaviors.8, 9 However, little is known about family and friend roles in clinical care of patients with chronic illness. Studies of general primary care patients find that 36-39% of elderly patients10-12 and 15%-26% of all adult patients13-15 are accompanied to their clinic visits. In this paper, we use the term “companion” for any non-professional family member or friend who accompanies the patient into the exam room. These companions often aim to facilitate patient-PCP communication and give emotional support during the visit.12, 15, 16 For example, companions might list questions for the provider, take notes during the visit, organize records of home symptoms or test results, manage prescriptions, support patient discussion of difficult topics, or help the patient negotiate medical decisions.16 Due to growing recognition of companions’ potential contributions to adults’ clinical care, healthcare organizations17-19 are advocating increased companion participation in care. For example, the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s Patient-Centered Medical Home certification criteria include recognition for increased involvement of family in self-management support programs and clinical care.20

Companion participation in clinical encounters could be particularly important to chronically ill patients, due to the complexity of their visits, their need for frequent clinical monitoring, and the importance of self-management to disease outcomes. However most studies of companion participation in clinical care have focused on elderly or severely disabled patients.10-12, 16, 21-23 In this study, we examine how often companions participate in primary care visits for adults with diabetes or heart failure who are functionally independent (defined as independence with basic activities of daily living). We then examine which patient characteristics are associated with higher likelihood of regular companion participation in care, focusing on patient characteristics that have been associated in other studies with a greater risk of poor chronic illness outcomes, such as low health literacy and depression symptoms.

Because patient-centered decision making and a strong patient-provider relationship is important for functionally independent chronically ill patients, companions may also interfere with patient-provider communication or even diminish patients’ confidence in self-management.9, 24 Therefore, we asked patients about their positive and negative experiences with companion participation and examined whether companion participation in clinical encounters was associated with patient satisfaction with their PCP. PCPs may also struggle with companion participation, due to high demands on the chronic illness visit and difficulties handling triadic (patient-companion-physician) communication. For example, companions may use visit time to discuss their own health issues or may take attention away from shared patient-physician decision making.25 Therefore we asked PCPs about their experiences with companion participation and examined PCP training and practice attributes associated with negative perceptions of companion participation.

Methods

Sample

We surveyed adult patients and physicians affiliated with the University of Michigan Healthcare System by mail. Patients were identified through health system diabetes and heart failure registries (See Appendix A for registry inclusion criteria). Patients are removed from the registry if their physician designates permanent cognitive impairment or limited life expectancy. Five hundred diabetes patients were randomly sampled from two strata: glycemic control at American Diabetes Association (ADA) goal (last HbA1C<7%) or not at ADA goal (last HbA1C>=7%). We were unable to distinguish type 1 from type II diabetes using registry data, but patients seeing an endocrinologist as their primary care physician were excluded. 500 heart failure patients were randomly sampled from four strata based on heart failure severity (lower ejection fraction (EF) is correlated with more severe symptoms, normal EF=55-80%): last measured EF < 40%, last EF 40-55%, last EF 55-80% with previous EF <40%, and last EF 55-80% with no history of abnormal EF. Respondents were ineligible if they indicated they were not aware of their diabetes or heart failure diagnosis (N=90), receiving cancer treatment (N=16), diagnosed with a memory disorder (N=16), receiving help with basic activities of daily living (N=29), or unable to understand English (N=1). All 126 health system physicians with assignments in general internal medicine, family medicine, or geriatrics were mailed a survey. Physicians who later reported they did not see primary care patients were ineligible (N=6). This study was approved by the University of Michigan Health System Institutional Review Board.

Patient Measures

Patient Independent Variables

See Appendix B for item wording, response options, and scaling methods. Each patient model contained a subset of the independent variables described here.

Sociodemographics and Health Literacy

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education were determined through survey questions. Inadequate health literacy was measured with one of three questions individually validated against the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults.26 The two other questions ask whether help is obtained from others to read or understand health information, so they could confound patient literacy with our measure of companion participation in care.

Health Status

Respondents who reported any activity limitations were considered to have functional limitations. Self-rated health status (SRHS) was measured using a standard 5 point scale.27 Because functional limitations were highly correlated with SRHS only one could be included in each model. We included functional limitations in models of companion participation, based on links to family assistance with medical care,10, 11 and we included SRHS in models of satisfaction with physician, as SRHS is associated with patient satisfaction.28 Respondents indicated whether they had any of 13 chronic comorbid conditions. Depressive symptoms were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-2.29

Family Structure and Function

Individual survey items measured marital/partner status and active care of minor children. Satisfaction with family function was measured with the Family APGAR.30

Patient Outcome Measures

Companion Participation in Patient PCP Visits

Patients answered whether “one of your family members or friends comes in the exam room with you for your doctor’s visit”. Patients who had a visit companion at all in the last 12 months were then asked, “When a friend or family member talks to your doctor, how often have you had the following experiences:”, followed by specific experiences. Respondents whose family or friends never talk to their PCP (N=162) were asked to skip the experience questions.

Patient satisfaction with PCP care

Patient satisfaction was measured with a three-item scale adapted from the Endorsement of Physician Scale.31 One item from the scale was changed from ‘patient willingness to make a special effort to see their physician again’ to ‘patient satisfaction with the diabetes/heart failure care they receive from their PCP’.

PCP Measures

PCP Independent Variables

Physician sociodemographics

Age, sex, and race/ethnicity were determined with survey items.

Physician practice attributes

Physician follow-up visit length was determined with one survey item. Physician satisfaction with their practice environment was assessed with items adapted from the Physician Satisfaction Scale.32

PCP Outcome Measures

Physician experiences with companion participation

First, physicians were asked to estimate the percentage of their adult patients who had diabetes or heart failure and who did not need assistance with activities of daily living. Instructions explained that all survey questions pertained to these patients. Then physicians were asked, “When your diabetes or heart failure patients’ family members or friends talk to you about your patients’ care, how often have you had the following experiences?”, followed by specific experiences.

Physician barriers to companion participation

Physicians were asked, “How would you feel about talking with family members or friends of diabetes and heart failure patients more often? Talking to family members or friends of diabetes and heart failure patients…” followed by positive and negative items. These items were adapted from the Physician Belief Scale,33 which measures physician attitudes toward the biopsychosocial model of care.

Analysis

Patient Attributes Associated with Companion Participation

This multivariate logistic regression included independent variables empirically or hypothetically relevant to companion participation: patient sociodemographics, family structure, functional limitations, depressive symptoms, health literacy level, and whether other family members were patients of the same physician. Companion participation was indicated by companion accompaniment in the exam room some visits or more. An ordinal logistic regression model, including all five categories of companion participation as the dependent variable, was used in an alternate analysis. The bivariate association between number of comorbid conditions and companion participation significantly differed by patient registry condition, so an interaction term between comorbidities and registry condition was included.

Association Between Companion Participation and Patient Satisfaction with PCP Care

This multivariate logistic regression included independent variables empirically or hypothetically related to satisfaction with physician care: patient sociodemographics, functional limitations, comorbidities, depression symptoms, length of patient-PCP relationship, and patient visit frequency.

Imputation of Missing Data for Patient Independent Variables

While each independent patient variable had < 5% missing data, only 81% of the respondents had the full set of variables needed for these analyses. Therefore, we used multiple imputation by chained equations to create 10 replicates of the dataset that replaced missing independent variables with imputed values.34 Model results were comparable between non-imputed estimates and the average estimates over the 10 imputed datasets, so results from imputed data are reported. Outcome measures were not imputed and descriptive results are based on non-imputed data only.

PCP Attributes Associated With Physician Barriers to Companion Participation

Because very little data was missing on the physician surveys, this multivariate logistic regression model used non-imputed data. Model independent variables were PCP sociodemographics, specialty training, and practice environment. The outcome was agreement with at least one barrier to companion participation.

Results

Of 590 returned patient surveys, 439 were from eligible participants (Council of American Survey Research Organizations [CASRO] response rate35 59%). 88 eligible PCP surveys were returned (CASRO response rate 73%).

Respondent Characteristics

Forty-eight percent of patient respondents were sampled from the heart failure registry and 52% from the diabetes registry. Fifty-four percent of all patient respondents were male, 68% were married, and 25% were caring for minor children. Patient age ranged from 25 to 95 years, with 40% of respondents between the ages of 51 and 64 years old. Fifty-eight percent reported functional limitations, and 36% reported fair or poor health status. Among PCPs, 48% were men, 57% were trained in general internal medicine, and 43% in family practice.

PCP relationship with patients and companions

Patients had known their PCP an average of 6.9 years with a mean of 3.7 PCP appointments in the past year. Forty-two percent of patients reported that their PCP provided health care for other family members. Fourty-eight percent of patients had companions in the PCP exam room at least sometimes. 13% of respondents reported regular companion – PCP phone contact, and 2% regular letter or email contact. However, only 3 respondents had regular phone or mail contact between friends or family and physicians without having regular PCP visit companions, so we could not examine those patients’ experiences separately.

Patient characteristics associated with companion participation in the PCP visit

In multivariate models adjusted for patient sex and age (Table 2), independent patient correlates of accompaniment into the exam room included being married/partnered (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] 3.7, CI 1.9-7.1) and satisfaction with family function (AOR 2.4, CI 1.4-4.2). Caring for minor children was associated with lower odds of companion participation in clinic visits (AOR 0.5, CI 0.3-0.98). Patients with low health literacy (AOR 2.9, CI 1.4-5.7), no college education (AOR 2.4, CI 1.4-4.1) or higher levels of depression symptoms (AOR 1.3, CI 1.1-1.6) were more likely to have companion participation in their visits. Patients with functional limitations (AOR 1.9, CI 1.1-3.4) were also more likely to have companion participation, but the effect of comorbid illness varied by the patient’s registry condition (interaction term p=0.01). This interaction indicated that heart failure registry patients were accompanied regardless of patient comorbidities, while diabetes registry patients were more likely to have companions when patients had 4 or more comorbid illnesses. The alternate ordinal logistic regression model gave similar results (not reported).

Table 2. Patient Characteristics Associated with Companion Participation in Clinic Visits Multivariable Logistic Regression Results#.

|

Dependent Variable:

Visit companion at least sometimes (Model N=422) |

|

|---|---|

| Independent Variables | OR [95% CI] |

| Married/Partnered | 3.7 [1.9, 7.1]*** |

| Inadequate Health Literacy | 2.9 [1.4, 5.7]** |

| Less than college education | 2.4 [1.4, 4.1]** |

| High Satisfaction with Family Function | 2.4 [1.4, 4.2]** |

| PCP cares for other family members | 2.2 [1.3, 3.8]** |

| Have Functional Limitations | 1.9 [1.1, 3.4]* |

| Increasing Depressive Symptoms | 1.3 [1.1, 1.6]** |

| Age (reference: <50) | |

| 51 - 64 | 0.7 [0.3, 1.4] |

| 65 - 74 | 0.7 [0.3, 1.7] |

| > 75 | 2.0 [0.8, 5.1] |

| Male | 1.1 [0.6, 1.9] |

| Hispanic/Non-Caucasian | 0.8 [0.4, 1.8] |

| Caring for one or more minor children | 0.5 [0.3, 0.98]* |

| Heart Failure Registry | 10.2 [3.7, 27.9]*** |

| Comorbidities (reference: 0-1) | |

| 2-3 | 2.3 [0.9, 5.9] |

| 4-10 | 3.7 [1.3, 10.5]* |

| Heart Failure * 2-3 Comorbidities | 0.4 [0.1, 1.5] |

| Heart Failure * 4-10 Comorbidities | 0.2 [0.1, 0.7]* |

Using dataset with imputed values for missing data

See Appendix B for items/calculations used to create Independent Variables

p <0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Patient experiences when companions talk to their PCP

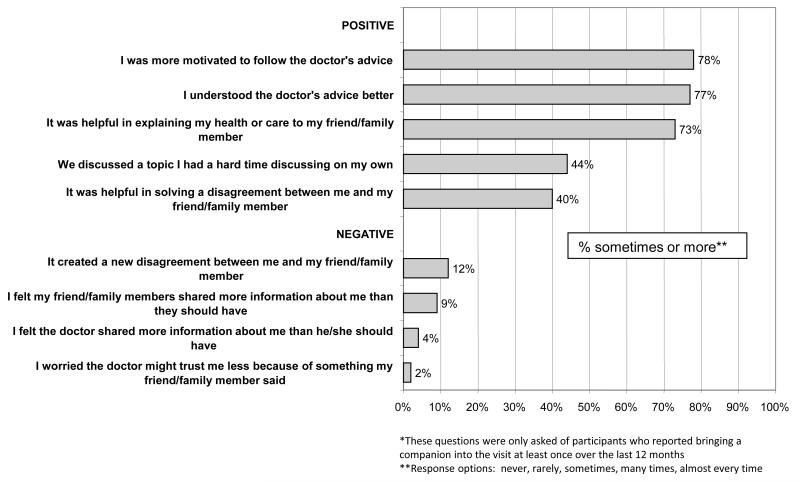

Looking at survey responses from only those patients that reported bringing a companion into the visit, more patients reported positive experiences much more frequently than negative experiences (Figure 1). Over 70% felt more motivation to follow the physician’s advice and better understanding of physician instructions when a companion participated. Forty-four percent said companion participation facilitated a difficult discussion with their PCP, and 40% solved a family disagreement about their health care. However, 12% said companion participation created new disagreements about their care, and 4% reported physicians shared “more information than they should have”.

Figure 1. Companion Experiences With Family Participation In PCP Care.

“When your friends or family talk to your [primary care] doctor, how often have you had the following experiences?” (N=193*)

Association between companion participation and patient satisfaction with PCP care

In multivariate analysis, patients who had regular companion participation in visits were more likely to have high satisfaction with their PCP (AOR 1.7, CI 1.1-2.7). See Table 3 for full model results.

Table 3.

Association between Companion Participation in Doctor Visit with Patient Satisfaction with PCP Care: Multivariate Logistic Regression Results#

| Dependent Variable: Patient Satisfaction with PCP Model N = 411 AOR (95%CI) |

|

|---|---|

| Independent Variables | |

| Visit companion at least sometimes | 1.7 (1.1-2.7)* |

| Age (reference: <50 years) | |

| 51 - 64 | 0.97 (0.5-1.8) |

| 65 - 74 | 1.2 (0.6-2.3) |

| > 75 | 0.8 (0.4-1.7) |

| Male | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) |

| Hispanic/Non-Caucasian | 2.3(1.3-4.3)** |

| Less than college education | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) |

|

Self-Rated Health Status

(reference: excellent/very good) |

|

| Good | 1.2 (0.7-2.1) |

| Fair/Poor | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) |

| Comorbidities (reference: 0-1) | |

| 2-3 | 0.7 (0.4-1.3) |

| 4-10 | 0.8 (0.4-1.5) |

| Increasing Depressive Symptoms | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) |

| Months known PCP | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) |

| Appointments with PCP in last 12 months | 1.1 (1.03-1.2)** |

Based on imputed data set, however key independent variable “Visit companion at least sometimes” and outcome variable were not imputed

p<0.05

p<.01

See Appendix B for item wording and scaling and Table 1 for variable distributions

PCP experiences when families participate in patient care

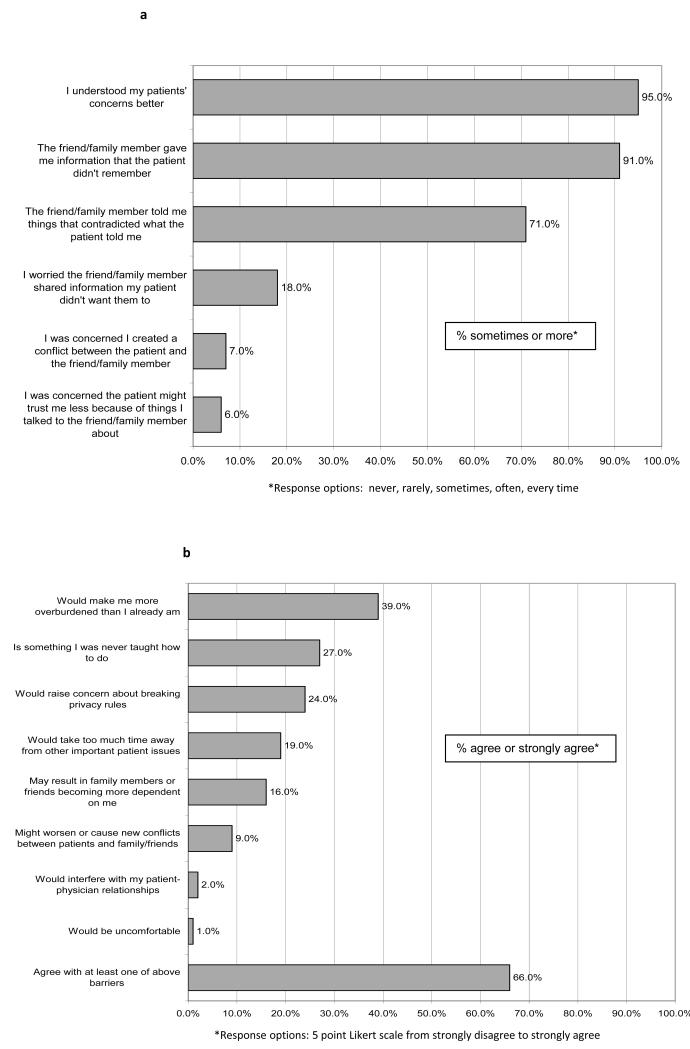

As shown in Figure 2a, 95% of PCPs felt they understood patient concerns better when companions participated in patient visits. While 71% reported companions often contradict things the patient told them, only 18% felt companions were sharing information the patient did not want them to share, and 6-7% experienced patient-companion conflicts or worse doctor-patient relationships when companions participated in care.

Figure 2. a: Physician Experiences when Companions Participate in Patient’s PCP Care.

“When your diabetes or heart failure patients’ friends or family talk to you about your patient’s care, how often have you had the following experiences?”

b: Physician Barriers to More Companion Participation

“How do you feel about talking with family and friends of diabetes or heart failure patients more often?”

PCP barriers to increasing companion participation

Sixty-six percent of PCPs endorsed at least one barrier to increased companion participation (Figure 2b). Thirty-nine percent of PCPs felt companions would cause them to be more overburdened, 19% felt they would take too much time away from important patient issues, and 16% worried companions would become too dependent on them. Twenty-seven percent of PCPs said they were not trained in companion communication techniques. In a multivariate analysis, general internists were more likely to report barriers to increased companion participation (AOR 3.9, 95% CI 1.4,11.3) than family practitioners (reference group, analysis not shown in tables). Follow-up appointment length and satisfaction with practice environment were not independently associated with physician barriers to companion participation.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of companion participation in clinical encounters of adult, functionally independent, chronically ill patients over a wide range of ages. Almost half of these adults with diabetes or heart failure had regular companions in patients’ PCP visits, regardless of patient sex and age. Companion participation was increased for patients with depressive symptoms or low health literacy. Patients who reported having a companion accompany them to clinic visits and physicians reported positive experiences with companion participation much more often than negative experiences, and in adjusted models companion participation was associated with patient satisfaction with PCP care. However 66% of PCPs reported at least one barrier to increasing companion participation in patient encounters.

These findings indicate that many patients with diabetes or heart failure may have family members or friends who participate in their clinic visits. This has significant implications for patients and clinicians alike, as companions represent a potential source of support for the clinical care of these patients. This study assesses companion participation among a population-based sample, instead of participation per visit as most previous studies have done.8, 10, 13-15, 23 This method better defines the potential impact of companion participation for this patient population. Clinical programs could tap into this existing support resource by developing explicit roles for companions in supporting clinical care, and tools to help them carry out these roles more effectively.

While patient functional limitations, depression and low education level have been associated with visit companionship in studies of elderly primary care patients,10-12, 22 our study is unique in examining the relative effects of a wide range of patient and family level determinants of participation among patients with chronic illnesses. We found that patients with more complex management issues and those particularly vulnerable to worse outcomes are also more likely to involve companions in their clinical care. These findings suggest that participation programs could focus on companion roles specifically targeted to these patients. For example, companions of diabetes or heart failure patients with low-health literacy might support patient understanding of provider instructions and record keeping. Companions of patients with multiple chronic conditions might help patients prioritize concerns for their physician visit and assist in monitoring lower priority conditions. Companions of diabetes or heart failure patients with co-morbid depression might use tools to support prescription adherence, or receive training in techniques to increase patient confidence in executing self-management tasks.36, 37 These findings also raise important questions about the reasons why patients with low literacy, more depressive symptoms, and more comorbidities are more likely to report companion participation in their clinic visits. Are these patients more likely to ask the companions? Do they need the companions more? Do the companions insist on joining more? These are questions that should be examined in future research to better understand and address factors that influence rates of companion participation in clinic visits with patients with heart failure or diabetes.

The benefits of companion participation in clinic visits that a majority of respondents reported, such as better patient understanding of provider advice and easier discussion of difficult topics, reinforce previous findings that companions of elderly patients see their role as enhancing patient-provider communication and providing emotional support. Studies examining the prospective impact of companion participation on patient comprehension, self-efficacy, care processes completed, and clinical outcomes are needed. Two studies of elderly patients16, 25 also found that accompanied patients had negative experiences, including less speaking time and less shared decision making with their provider. However patients in our study rarely reported patient-companion conflict. Direct observation of companion-patient-physician interactions could help define future areas of intervention to minimize negative impacts of visit companions.

Our study was unique in assessing physician experiences with visit companions and found several addressable clinic based barriers. For example, 24% of PCPs reported concern about privacy rules, yet the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has published guidelines for HIPPA compliant physician communication with companions.38 Simple tools, such as asking all patients to designate companions with whom they are willing to share information, could further reduce clinician concerns about privacy. Barriers involving disagreements or conflicts among physicians, patients, and companions could be more difficult to address. Our data do not reveal whether these conflicts have positive or negative effects on physician-patient understanding. For example, companions who contradict the patient could help clarify important information, or increase confusion and damage patient-physician trust. Physician management of conversations with accompanied patients could help keep companion contributions positive, yet physicians in our survey felt they lacked training in handling companion participation. Of note, family practitioners, who are more likely to have training in family communication than internists, reported significantly less barriers to companion participation. There is evidence that provider training can improve these skills,39, 40 and existing practical guides to physician-companion communication could be used in physician training.41 In addition, tools designed to help caregivers of disabled patients optimize their communication with clinicians42 could be adapted for companions of chronically ill patients.

Increased physician burden was the most frequent physician concern in our survey, although time allotted for follow-up visits and physician satisfaction with practice support were not associated with perceived barriers to companion participation in multivariate analysis. The scant evidence we have suggests that companion participation does not lengthen the visit,25, 43 and clinicians can bill Medicare for time spent counseling companions as part of a medically necessary patient visit.44 In addition, if effectively executed, companion assistance with patient-provider communication and record keeping might streamline visits for patients with complex chronic illness. However programs that increase companion participation in care will have to balance new care processes against concerns about physician burden. Strategies to ameliorate additional physician burden from companion participation could include physician training in managing triadic communication, delegating some companion communication to non-physician clinicians,45 and tools which help companions focus on key issues during the visit.

Our study must be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the generalizability of our results is limited by our sample, which was drawn from one hospital-based health system, serving a relatively educated patient population with little racial/ethnic variation. In addition, patients with other chronic diseases, such as rheumatologic diseases, might have different patterns of results. The experiences of patients without current companion participation, who may have had negative experiences with companion participation in the past, are not represented. Furthermore, our sample of clinicians did not include non-physician clinicians, who may be more confident and experienced with companion interactions than physicians. Second, while our study design allowed us to make patient population based estimates, rather than visit based estimates, patient reports of visits up to 12 months earlier are subject to recall bias. Third, all estimates were based on self-report, which could produce less accurate descriptions of experiences than direct observation. Fourth, the presence of companions in the exam room does not reveal the specific level or type of companion participation in patient care. Development of new measures of companion participation in clinical care for this patient population are needed, as companion roles are likely to differ from those for more debilitated patients.46 Finally, all analyses were done with cross-sectional data, making causal inference difficult. This is most concerning when evaluating patient satisfaction, as more satisfied patients may be more likely to include companions in their physician visits.

In conclusion, family members and friends who accompany patients could represent an important source of support for the clinical care of diabetes and heart failure patients of all ages. Future interventions to increase effective companion participation in the clinical encounters of these patients should target vulnerable patient groups, develop companion roles that enhance patient-provider communication, and aim to efficiently integrate companions into the clinical team.

Supplementary Material

Table 1. Patient and Physician Participant Characteristics# (Total N surveyed 439).

| Patients | Total N (not-missing) | % (n) with highlighted value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampled from Heart Failure Registry a | 439 | 48% (211) | |

| Age (years) | 421 | ||

| < 50 | 16 % (62) | ||

| 51 - 64 | 40% (162) | ||

| 65 - 74 | 23% (101) | ||

| > 75 | 21% (96) | ||

| Male | 426 | 54% (223) | |

| Hispanic/Non-Caucasian | 426 | 13% (61) | |

| Less than College Education | 430 | 32% (149) | |

| Inadequate Health Literacy | 425 | 19% (90) | |

| Married/Partnered | 434 | 68% (293) | |

| Currently caring for minor children | 418 | 25% (106) | |

| High Satisfaction with Family Function | 412 | 41% (169) | |

| Comorbidities | 424 | ||

| 0-1 | 30% (121) | ||

| 2-3 | 42% (174) | ||

| 4-10 | 29% (129) | ||

| Have Functional Limitations | 404 | 58% (233) | |

| Self-Rated Health Status | 419 | ||

| Excellent/Very Good | 23% (93) | ||

| Good | 40% (169) | ||

| Fair/Poor | 36% (157) | ||

| Mean | SD | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | 413 | 3.2 | 1.6 |

| Primary Care Physicians (Total N 88) | N | % (n) | |

| Male | 87 | 48% (42) | |

| Non-Caucasian b | 87 | 15% (13) | |

| Specialty | 88 | ||

| General Medicinec | 57% (50) | ||

| Family Practice | 43% (38) | ||

| Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 87 | 43.8 | 9.0 |

| Physician satisfaction with practice environment | 87 | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| Time for typical follow-up appointment (minutes) | 86 | 19.1 | 6.3 |

|

Patient-Reported Characteristics of Physician- Patient and Physician–Companion Relationships (Total N surveyed 439) |

Total N (not-missing) | % (n) with highlighted value | |

| Patient’s PCP cares for other family members | 422 | 42% (180) | |

| Patient accompanied into PCP exam room | 422 | ||

| Every Visit | 18% (77) | ||

| Most Visits | 13% (56) | ||

| Some Visits | 18% (74) | ||

| Rarely | 15% (62) | ||

| Never | 36% (153) | ||

| High patient satisfaction with PCP care | 419 | 42% (174) | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Months known PCP | 414 | 82.8 | 70.5 |

| Appointments with PCP in last 12 months | 419 | 3.7 | 2.7 |

Based on non-imputed data

Patients were sampled from either a Heart Failure or a Diabetes Registry. Patients in one registry could have the other condition, however once patients were sampled from the heart failure registry they were ineligible to be sampled from the diabetes registry.

No physician respondents reported Hispanic ethnic background

General Medicine includes General Internal Medicine, Geriatrics and dual Medicine/Pediatrics training

See Appendix B for item wording, scoring, and scaling

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program, the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (NIH # DK020572) and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (NIH #UL1RR024986). John Piette is a VA HSR&D Research Career Scientist. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. We are grateful to Alice Beckman, Jessica Forestier, Aleksandra Jankovic, Susan Lopez, Melissa Mashni, Amanda Pudenz, the UMHS Chronic Disease Registries staff, and the AAVA/UM QUICCC staff for their assistance with this project.

References

- 1.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases . National Diabetes Statistics, 2007 Fact Sheet Bethesda, MD. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobbs FDR. Clinical burden and health service challenges of chronic heart failure. Oxford University Press; 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, Smith DM, Kerr EA. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002 Apr;17(4):243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heisler M, Cole I, Weir D, Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Does physician communication influence older patients’ diabetes self-management and glycemic control? Results from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007 Dec;62(12):1435–1442. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.12.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rost K, Roter D. Predictors of recall of medication regimens and recommendations for lifestyle change in elderly patients. Gerontologist. 1987 Aug;27(4):510–515. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.4.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the patient’s agenda: have we improved? Jama. 1999 Jan 20;281(3):283–287. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. Missing clinical information during primary care visits. Jama. 2005 Feb 2;293(5):565–571. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayers SL, Riegel B, Pawlowski S, Coyne JC, Samaha FF. Social support and self-care of patients with heart failure. Ann Behav Med. 2008 Feb;35(1):70–79. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosland AM, Heisler M, Choi H, Silveira M, Piette JD. Family influences on self management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: Do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illness. doi: 10.1177/1742395309354608. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasser M. Elderly Patients and Their Accompanying Caregivers on Medical Visits. Research on aging. 2001;23(3):326. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silliman RA, Bhatti S, Khan A, et al. The care of older persons with diabetes mellitus: families and primary care physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996 Nov;44(11):1314–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01401.x. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Hidden in plain sight: medical visit companions as a resource for vulnerable older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Jul 14;168(13):1409–1415. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Botelho RJ, Lue BH, Fiscella K. Family involvement in routine health care: a survey of patients’ behaviors and preferences. J Fam Pract. 1996 Jun;42(6):572–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Main DS, Holcomb S, Dickinson P, Crabtree BF. The effect of families on the process of outpatient visits in family practice. J Fam Pract. 2001 Oct;50(10):888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schilling LM, Scatena L, Steiner JF, et al. The third person in the room: frequency, role, and influence of companions during primary care medical encounters. J Fam Pract. 2002 Aug;51(8):685–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y, Takayama T. Physician-elderly patient-companion communication and roles of companions in Japanese geriatric encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2005 May;60(10):2307–2320. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Healthcare Workforce. 2008 http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2008/Retooling-for-an-Aging-America-Building-the-Health-Care-Workforce.aspx.

- 18.Rosland A-M. Sharing the Care:The Role of Family in Chronic Illness. [Accessed 08-16-2009]. 2009. http://www.chcf.org/documents/chronicdisease/FamilyInvolvement_Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.United Hospital Fund Next Step In Care: Family Caregivers & Healthcare Professionals Working Together. nextstepincare.org.

- 20.National Committee for Quality Assurance Standards and Guidelines for Physician Practice Connections – Patient Centered Medical Home (PC-PCMH) 2010 www.ncqa.org/tabid/629/Default.aspx.

- 21.Clayman ML, Roter D, Wissow LS, Bandeen-Roche K. Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Apr;60(7):1583–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prohaska TR, Glasser M. Patients’ Views of Family Involvement in Medical Care Decisions and Encounters. Research on aging. 1996;18(1):52–69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayers S, White T, Zubritsky C, Oslin D. Family involvement in the care of healthy medical outpatients. Fam Pract. 2006;23:317–324. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiIorio C, Shafer PO, Letz R, et al. Project EASE: a study to test a psychosocial model of epilepsy medication managment. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2004 Dec;5(6):926–936. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene MMG, Majerovitz SSD, Adelman RRD, Rizzo CC. The effects of the presence of a third person on the physician-older patient medical interview. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(4):413–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb07490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Family Medicine. 2004 Sep;36(8):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997 Mar;38(1):21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao H, Barber JP. The Effect of Perceived Health Status on Patient Satisfaction. Value in Health. 2008;11(4):719–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003 Nov;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smilkstein G, Ashworth C, Montano D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J Fam Pract. 1982 Aug;15(2):303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kravitz R, Bell R, Azari R, Krupat E, Kelly-Reif S, Thom D. Request fulfillment in office practice: antecedents and relationship to outcomes. Med Care. 2002;40(1):38–51. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grembowski D, Ulrich CM, Paschane D, et al. Managed care and primary physician satisfaction. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003 Sep-Oct;16(5):383–393. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.5.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashworth CD, Williamson P, Montano D. A scale to measure physician beliefs about psychosocial aspects of patient care. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19(11):1235–1238. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90376-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlin JB, Galati JC, Royston P. A new framework for managing and analyzing multiply imputed data in STATA. STATA Journal. 2008;8(1):49–67. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynn P, Beerten R, Laiho J, Martin J. Recommended standard final outcome categories and standard definitions of response rate for social surveys. The Institute for Social and Economic Research; Colchester, Essex: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams GC, Deci EL, Ryan RM. Building health-care partnerships by supporting autonomy: Promoting maintained behavior change and positive health outcomes. In: Suchman A, Hinton-Walker P, Botelho RJ, editors. Partnerships in healthcare: Transforming relational process. University of Rochester Press; Rochester: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams GC, Gagne M, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Facilitating autonomous motivation for smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 2002 Jan;21(1):40–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.US Department of Health and Human Services A Patient’s Guide to the HIPAA Privacy Rule: When Healthcare Providers May Communicate About You with Your Family, Friends, or Others Involved in Your Care. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/consumers/consumer_ffg.pdf.

- 39.Shapiro J, Lenahan P, Masters M. Psychosocial performance of family physicians. Fam Pract Res J. 1993 Sep;13(3):249–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medalie JH, Zyzanski SJ, Langa D, Stange KC. The family in family practice: is it a reality? The Journal of family practice. 1998;46(5):390–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDaniel S, Campbell T, Hepwroth J, Lorenz A. Family Oriented Primary Care. 2nd ed. Springer; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Family Caregivers Association Making the most of a visit to the doctor: what every family caregiver needs to know. http://thefamilycaregiver.org/pdfs/Visit_To_The_Doctor_Brochure.pdf.

- 43.Beisecker AE. The influence of a companion on the doctor-elderly patient interaction. Health Commun. 1989;1(1):55–70. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc0101_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Tip sheet for providers: Caregiving Education. CMS Publication No. 11390-P www.caregiving.org/data/CMS_Tip_Sheet_for_Providers_Caregiving_Education.pdf.

- 45.Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Siminerio LM. Physician and nurse use of psychosocial strategies in diabetes care: results of the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study. Diabetes Care. 2006 Jun;29(6):1256–1262. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosland AM, Piette JD. Emerging models for mobilizing family support for chronic disease management: A structured review. Chronic Illness. doi: 10.1177/1742395309352254. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.