Abstract

Arginine residues are broadly employed for specific biomolecular recognition, including in protein-protein, protein-DNA, and protein-RNA interactions. Arginine recognition commonly exploits the potential for bidentate electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions. However, in arginine residues, the guanidinium functional group is located at the terminus of a flexible hydrocarbon side chain, which lacks the functionality to contribute to specific arginine-mediated recognition and may entropically disfavor binding. In order to enhance the potential for specificity and affinity in arginine-mediated molecular recognition, we have developed an approach to the synthesis of peptides that incorporates an α-guanidino acid as a novel arginine mimetic. α–Guanidino acids, derived from α-amino acids, with guanylation of the amino group, were incorporated stereospecifically into peptides on solid phase via coupling of an Fmoc amino acid to diaminoproprionic acid (Dap), Fmoc deprotection, guanylation of the amine on solid phase, and deprotection, generating a peptide containing an α-functionalized arginine mimetic. This approach was examined via the incorporation of arginine mimetics into ligands for the Src, Grb, and Crk SH3 domains at the site of the key recognition arginine. Protein binding was examined for peptides containing guanidino acids derived from Gly, l-Val, l-Phe, l-Trp, d-Val, d-Phe, and d-Trp. We demonstrate that paralog specificity and target site affinity may be modulated via the use of α-guanidino acid-derived arginine mimetics, generating peptides that exhibit enhanced Src specificity via selection against Grb and peptides that reverse the specificity of the native peptide ligand, with enhancements in Src target specificity of up to 15-fold (1.6 kcal/mol).

Keywords: Peptides, amino acids, peptidomimetics, guanidiniums, protein-protein interactions

Introduction

Arginine residues have unique biomolecular recognition properties owing to the guanidinium functional group, which displays 5 coplanar hydrogen bond donors, a diffuse positive charge, and delocalized pi electrons.[1] The guanidinium group is particularly adept at multidentate hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, leading to highly favorable interactions with phosphate, carboxylate, and sulfate anions.[2] These characteristics often result in the observation of obligatory arginine recognition in the interactions of proteins with DNA, RNA, lipids, carbohydrates, and other proteins, as observed in cell-cell communication and extracellular signaling, in intracellular signal transduction pathways, and in the control of transcription and translation, among many other applications.[1a, 3] Arginine-rich peptides also have special application as cell-penetrating peptides, in a manner that is dependent on the guanidinium functional groups of the peptides.[4]

One potential limitation of arginine-mediated recognition is the presence of the guanidinium group at the end of linear alkyl side chain. The three methylenes (−CH2- groups) of arginine residues may enhance target site affinity via the hydrophobic effect, but their inherent flexibility, which allows recognition through one or more of multiple side chain rotamers, imposes a potential cost in both entropy and in recognition specificity, as the linear alkyl side chain can readily adapt to different structures.[5] Moreover, the linear side chain lacks additional features (e.g. functional groups or stereochemistry) that could enhance specific target recognition.

A broad interest in the pharmacological control of arginine-mediated interactions has led to the development of a range of small molecule arginine mimetics.[6] We recently described the stereospecific synthesis of the novel arginine mimetic α-guanidino acids, in which the α-amino group of standard α-amino acids is guanylated to generate a guanidinium group with adjacent stereochemistry and functional groups.[7] In that work, we focused on the synthetic development of α-guanidino acids as arginine mimetics in small molecules. However, we envisioned that α-guanidino acids could function as arginine mimetics within peptides, via the conjugation of an amino acid to the β- or α-amino group of a diaminoproprionic acid (Dap) residue and subsequent guanylation (Figure 1). This approach would have the potential to introduce both stereochemistry and functional groups for molecular recognition adjacent to the key guanidinium, providing the possibility of enhanced target specificity and/or affinity. Moreover, because the approach is based on guanylated α-amino acids, it has the potential to introduce a wide range of α-functional groups, owing to the broad availability of structurally and functionally diverse α-amino acids. Indeed, in the work of Wells, Arkin, and coworkers, small molecules containing α-guanidino acids could dramatically modulate affinity for interleukin-2, with both stereochemistry and side chain significantly affecting target recognition.[7d-h] This work provided critical proof of concept for the application of α-guanidino acids in specific target recognition, although their synthetic approach involved separation of diastereomers of α-guanidino acid-containing compounds.

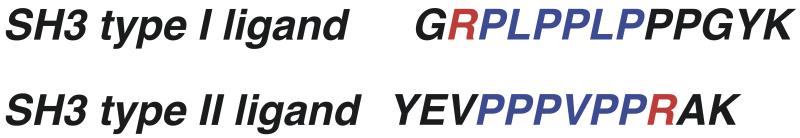

Figure 1.

Arginine, homoarginine, and Dap-derived α-guanidino acid arginine mimetics, which allow placement of functional groups and introduction of stereochemistry adjacent to the guanidinium. Incorporation of the α-guanidino acid on the β-amino group of Dap (yielding hArg(gXaa) residues) allows the incorporation of α-guanidino acids at any position in a peptide sequence. In contrast, incorporation on the α-amino group of Dap (yielding Arg(gXaa) residues) directly mimics the length of the arginine side chain, but can only be readily employed at the N-terminus of an α-peptide due to the resultant β-peptide backbone with this substitution.

To explore the application of α-guanidino acid-based arginine mimetics, we have developed approaches to the synthesis of peptides containing α-guanidino acids and tested these arginine mimetics in the challenging context of paralog-specific recognition of SH3 domains by proline-rich peptides.

Results

Design of peptides containing α-guanidino acids as novel arginine mimetics

We examined arginine-mediated recognition via α-guanidino acid arginine mimetics within the context of proline-rich ligands of SH3 domains.[8] SH3 domains are small (~60 amino acids) protein domains that are critical for protein-protein interactions in signal transduction. SH3 domains bind short proline-rich ligands with a typical PXXP motif. Because of the importance of SH3 domains in cell signaling, there has been substantial interest in developing inhibitors of SH3 domain-mediated protein-protein interactions.[9] However, the inherent flatness of the recognition surface has resulted in significant problems in achieving paralog specificity, that is, achieving specific recognition of one SH3 domain among the approximately 300 SH3 domains in the human proteome.[9f, 10] Challenges in achieving paralog specificity have resulted in a significant reduction in pharmaceutical efforts to target SH3 domains, compared to the peak interest in the 1990s, despite potential applications as therapeutics in cancer and other diseases.

SH3 domains typically bind peptides with one or more arginine residues at the N-terminus (type I) or the C-terminus (type II) of the recognition sequence.[8c, 9f, 11] Confounding attempts to achieve paralog specificity, it was recognized that a single SH3 domain could bind both type I and type II ligands, via a reversal of the orientation of ligand binding. Analysis of available high resolution structures of peptides bound to SH3 domains reveals that arginine recognition by SH3 domains involves a combination of electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions with the guanidinium and hydrophobic interactions with the arginine methylenes (Figure 2). Interestingly, there is considerable available hydrophobic surface area that is not employed in recognition, presumably to accommodate the diversity of ligands natively bound by SH3 domains. For example, in the Src SH3 domain (pdb 1qwf), the ligand arginine side chain is near the hydrophobic residues Trp42, Tyr55, and Thr22, whereas in the Grb2 SH3 domain (pdb 1sem) the ligand arginine is near Trp191, Ile202, Phe165, and the methylenes of Gln168 and Glu169.[11a, 11c, 11d, 12] We envisioned that the incorporation of functional groups adjacent to the guanidinium in an arginine mimetic could exploit the differences in the recognition surfaces in divergent SH3 domains and provide a locus to achieve paralog specificity. Given the importance of arginine residues in SH3 domain recognition of ligands, this approach provides the possibility of a general method to modulate target affinity in arginine-mediated recognition.

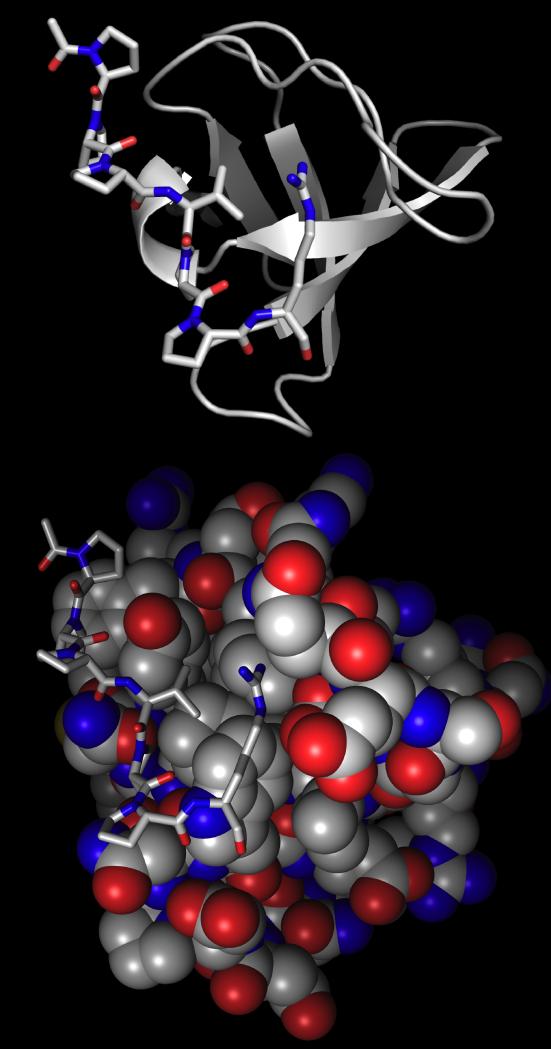

Figure 2.

SEM-5 (Grb2 homologue) SH3 domain (ribbon (top) or CPK (bottom)) (pdb: 1sem)[11c] bound to SH3 domain ligand from mSOS PPPVPPR (sticks). Bottom: CPK figure showing hydrophobic surface area (gray) around the arginine side chain.

To test this approach, we examined α-guanidino acid arginine mimetics in two peptide contexts: as a replacement for an N-terminal arginine in a type I SH3 domain ligand (hAMI and AMI) and as a replacement for a C-terminal arginine in a type II SH3 domain ligand (hAMII). In addition, within the context of a type I SH3 domain ligand, we examined both the use of the Dap α-amino and β-amino groups for conjugation of the α-guanidino acid, generating peptides that are formally (by side chain length) arginine (Arg(gXaa)) or homoarginine (hArg(gXaa)) equivalents. Both ligands were chosen to incorporate a single arginine residue, to simplify analysis and because a single properly-positioned arginine is both necessary and sufficient for SH3 domain binding.[11a, 11c, 11d, 12-13]

Stereospecific synthesis of peptides incorporating α-guanidino acids

In order to take advantage of the diversity of amino acid functionality and stereochemistry that is commercially available as standard Fmoc amino acids, as well as the benefits of solid phase peptide synthesis, we devised an approach to the synthesis of peptides containing α-guanidino acids that involves coupling of protected α-amino acids to an orthogonally (Mtt) protected diaminoproprionic acid (Dap) residue. In this approach, the peptide was fully synthesized, the protecting group on the Dap removed, and the Fmoc amino acid that is the α-guanidino acid precursor coupled by standard amide coupling conditions, followed by piperidine deprotection of the coupled α-amino acid and guanylation of the α-amino group using Moroder’s guanylating reagent[14] (Schemes 1-4). This approach was applied to the synthesis of both type I (Schemes 2-3) and type II (Scheme 4) SH3 domain ligand peptides. In order to test the application of α-guanidino acids in molecular recognition, including roles of stereochemistry and functional group identity, each peptide was synthesized to contain Dap conjugated to α-guanidino acids derived from glycine and from both l- and d- stereoisomers of the hydrophobic amino acids valine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan. These amino acids were chosen because of their hydrophobic surface area, their sterics, and because Phe and Trp are particularly prone to epimerization among canonical amino acids, and thus provide an appropriate test of the potential synthetic challenges in the synthesis of peptides containing α-guanidno acid arginine mimetics. As controls, the peptides with acetylated Dap were synthesized, which contain the side chain amide but lack the guanidinium group (i.e. equivalent to gGly with the guanidinium removed).

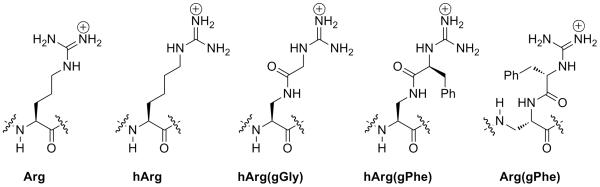

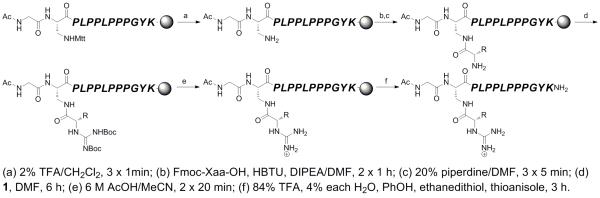

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Moroder’s guanylating reagent 1.[14] This synthesis differs from the published synthesis of 1 due to the replacement of HgCl2 employed in the original synthesis with the more convenient reagent EDCI.

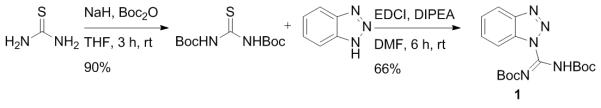

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of type II SH3 domain ligand peptides peptides containing N-terminal homoarginine-equivalent α-guanidino-acid arginine mimetics (hAMII(gXaa)).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of type I SH3 domain ligand peptides containing N-terminal homoarginine-equivalent α-guanidino acid arginine mimetics (hAMI(gXaa)).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of type I SH3 domain ligand peptides peptides containing N-terminal arginine-equivalent α-guanidino-acid arginine mimetics (AMI(gXaa)).

Previous work with small molecules containing α-guanidino acids suggested that typical peptide cleavage/deprotection conditions (i.e. 90% TFA) would lead to substantial or complete epimerization at the carbon α to the guanidinium group.[7a, 7c-h] Indeed, standard TFA cleavage of α-guanidino acid-containing peptides revealed evidence of significant epimerization (data not shown). However, in small molecules, after deprotection of the guanidine under mild conditions (0.5 M HCl), the free guanidium-containing α-guanidino acids were configurationally stable in 90% TFA.[7a] These results suggest that the Boc groups on α-guanidino acids are rather labile and might be removed under mild conditions.

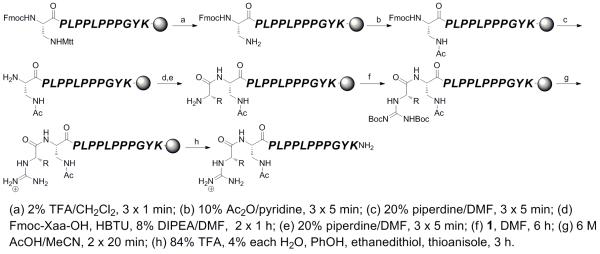

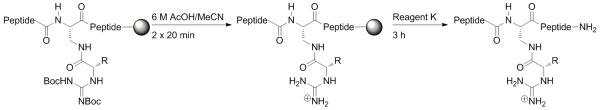

Based on these results, we devised a two-stage scheme for separate deprotection of the guanidine Boc groups and global deprotection/cleavage of the peptide from the resin (Scheme 5). A brief screening of deprotection conditions identified that guanidine Boc groups could be removed with no evidence of epimerization using 6 M AcOH in MeCN (2 × 20 minutes). This approach was then applied to all synthesized peptides, resulting in the generation of α-guanidino acid-containing peptides in good yield.

Scheme 5.

Two stage deprotection of peptides containing α-guanidino acid arginine mimetics. This approach was applied to the synthesis of all α-guanidino acid-containing peptides in this study, to prevent epimerization of the carbon α to the guanidinium group. The intermediate after guanidine Boc deprotection could be fully deprotected, as suggested by experiments with model compounds, or may potentially retain one guanidine Boc group.

In order to confirm the retention of stereochemical integrity in the synthesis of peptides containing α-guanidino acids, all peptides were characterized by NMR spectroscopy. TOCSY spectra of the peptides revealed that in all cases the diastereomers derived from l- and d-amino acids could be readily differentiated by NMR (Figure 4 and data not shown). Notably, in all cases the NMR data revealed no evidence of epimerization of the individual peptides, within the limits of detection (> 95% stereochemical purity). As Phe and Trp are the canonical amino acids most prone to epimerization, these data suggest generality of the methodology for the synthesis of α-guanidino acid-based arginine mimetics in peptides.

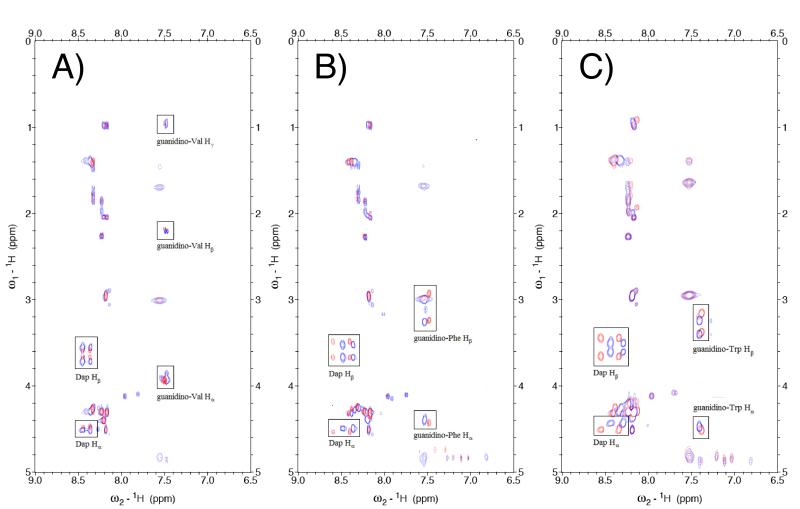

Figure 4.

Comparison of TOCSY crosspeaks of diastereomeric hAMII peptides (A) hAMII(gl-Val (red) versus hAMII(gd-Val) (blue); (B) hAMII(gl-Phe (red) versus hAMII(gd-Phe) (blue); and (C) hAMII(gl-Trp (red) versus hAMII(gd-Trp) (blue). Comparable spectra were obtained for diagnostic regions of the TOCSY spectra of all peptides, indicating stereoisomeric purity and the absence of epimerization on the conjugated α-guanidino acids. Critical crosspeaks from the Dap-conjugated α-guanidino acids are highlighted. Arginine mimetics have two amide protons for the Dap residue, from the backbone N-H and β N-H amides.

α-Guanidino acid-based arginine mimetics to modulate paralog-specific recognition of SH3 domains

All peptides were analyzed for their ability to function as ligands for the Src and Grb SH3 domains, which can bind identical ligands with similar affinity, and thus provide a test of the effects of α-guanidino acid-based arginine mimetics on both target affinity and specificity. As a control, to identify possible increases in affinity due to non-specific interactions, we also examined binding to the Crk SH3 domain, which can bind similar ligands but bound the parent single-arginine peptides in this study poorly. All peptides were labeled with fluorescein on the C-terminal lysine residue and dissociation constants (Kd) for all peptide-protein interactions determined via a fluorescence polarization-based binding assay (Figure 5, Tables 1-3).

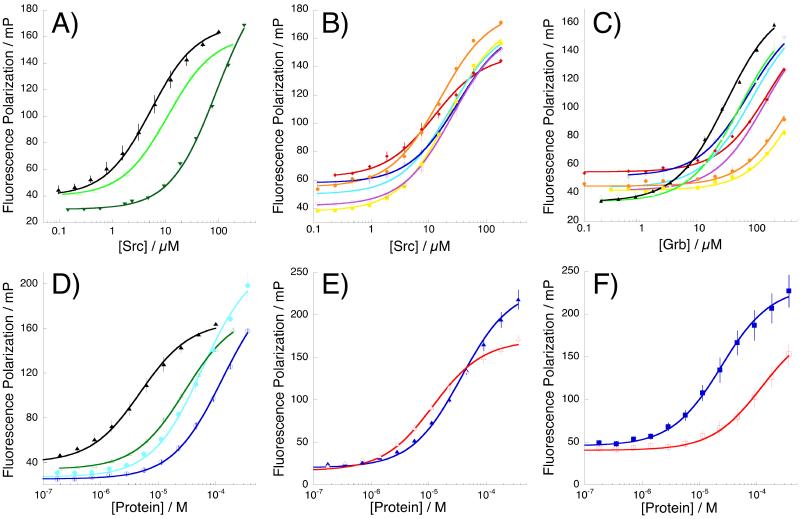

Figure 5.

Representative binding isotherms, showing data and comparisons of key arginine-mimetic peptides. mP = fluorescence polarization in millipolarization units (= polarization/1000). Error bars indicate standard error. (A) hAMI(Arg) (black triangles), hAMI(Dap-Ac) (dark green inverted triangles), and hAMI(gGly) (light green open triangles) binding to Src; (B) α-substituted hAMI arginine mimetic peptides binding to Src: hAMI(gl-Val) (magenta open squares), hAMI(gd-Val) (yellow closed squares), hAMI(gl-Phe) (cyan open circles), hAMI(gd-Phe) (orange closed circles), hAMI(gl-Trp) (blue open diamonds), hAMI(gd-Trp) (red closed diamonds); (C) α-substituted hAMI arginine mimetic peptides binding to Grb: hAMI(Arg) (black closed triangles); hAMI(gGly) (light green open triangles); hAMI(gl-Val) (magenta open squares), hAMI(gd-Val) (yellow closed squares), hAMI(gl-Phe) (cyan open circles), hAMI(gd-Phe) (orange closed circles), hAMI(gl-Trp) (blue open diamonds), hAMI(gd-Trp) (red closed diamonds); (D) hAMI(Arg) binding to Src (closed black triangles) and Grb (open green triangles); AMI(gl-Phe) binding to Src (closed cyan circles) and Grb (open blue circles); (E) hAMII(Arg) binding to Src (closed blue triangles) and Grb (open red triangles); (F) hAMII(gl-Trp) binding to Src (closed blue squares) and Grb (open red squares).

Table 1.

Dissociation constants of type I homoarginine-equivalent arginine mimetic peptides (hAMI).

|

Kd, μM |

Error | ΔG, kcal mol−1 |

ΔΔGaffinity, a kcal mol−1 |

ΔΔGspecificity, b kcal mol−1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Src | Arg | 5.3 | 0.3 | −7.2 | 0 | −1.0 |

| Dap-Ac | 91 | 5.3 | −5.5 | 1.68 | −0.7 | |

| hArg(gGly) | 11.1 | 0.2 | −6.7 | 0.44 | −0.9 | |

| hArg(gl-Val) | 25.5 | 1.3 | −6.2 | 0.93 | −1.0 | |

| hArg(gd-Val) | 22.5 | 1.1 | −6.3 | 0.86 | −1.9 | |

| hArg(gl-Phe) | 23.9 | 1.1 | −6.3 | 0.89 | −0.7 | |

| hArg(gd-Phe) | 15.9 | 0.6 | −6.5 | 0.65 | −2.0 | |

| hArg(gl-Trp) | 31.8 | 1.5 | −6.1 | 1.07 | −0.5 | |

| hArg(gd-Trp) | 12.6 | 1.1 | −6.7 | 0.52 | −1.5 | |

| Grb | Arg | 29 | 2 | −6.2 | 0 | |

| Dap-Ac | 320 | 104 | −4.8 | 1.42 | ||

| hArg(gGly) | 50 | 6 | −5.8 | 0.32 | ||

| hArg(gl-Val) | 141 | 12 | −5.2 | 0.93 | ||

| hArg(gd-Val) | 576 | 19 | −4.4 | 1.76 | ||

| hArg(gl-Phe) | 82 | 7 | −5.6 | 0.61 | ||

| hArg(gd-Phe) | 451 | 22 | −4.6 | 1.62 | ||

| hArg(gl-Trp) | 72 | 3 | −5.6 | 0.54 | ||

| hArg(gd-Trp) | 164 | 7 | −5.1 | 1.02 | ||

ΔΔGaffinity = ΔG (peptide) – ΔG (Arg).

ΔΔGspecificity = ΔGSrc – ΔGGrb for a given peptide. All peptides bound poorly to Crk (Kd > 250 μM). All experiments were conducted in PBS at 25 °C.

Table 3.

Dissociation constants of type II homoarginine-equivalent arginine mimetic peptides (hAMII).

|

Kd, μM |

Error | ΔG, kcal mol−1 |

ΔΔGaffinity, kcal mol−1 |

ΔΔGspecificity,b kcal mol−1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Src | Arg | 37 | 2 | −6.0 | 0 | +0.7 |

| Dap-Ac | 350 | 31 | −4.7 | 1.33 | −0.2 | |

| hArg(gGly) | 59 | 2.3 | −5.8 | 0.28 | −0.6 | |

| hArg(gl-Val) | 67 | 2.3 | −5.7 | 0.35 | −0.7 | |

| hArg(gd-Val) | 130 | 3.7 | −5.3 | 0.74 | −0.4 | |

| hArg(gl-Phe) | 58 | 1.8 | −5.8 | 0.27 | −0.5 | |

| hArg(gd-Phe) | 66 | 2.1 | −5.7 | 0.34 | −0.9 | |

| hArg(gl-Trp) | 24 | 1.2 | −6.3 | −0.26 | −1.0 | |

| hArg(gd-Trp) | 49 | 2.1 | −5.9 | 0.17 | −1.0 | |

| Grb | Arg | 12 | 0.7 | −6.7 | 0 | |

| Dap-Ac | 500 | 160 | −4.5 | 2.20 | ||

| hArg(gGly) | 166 | 12 | −5.1 | 1.56 | ||

| hArg(gl-Val) | 227 | 13 | −4.9 | 1.74 | ||

| hArg(gd-Val) | 270 | 31 | −4.9 | 1.84 | ||

| hArg(gl-Phe) | 128 | 8 | −5.3 | 1.40 | ||

| hArg(gd-Phe) | 319 | 44 | −4.8 | 1.94 | ||

| hArg(gl-Trp) | 121 | 10 | −5.3 | 1.36 | ||

| hArg(gd-Trp) | 244 | 24 | −4.9 | 1.78 | ||

ΔΔGaffinity = ΔG (peptide) – ΔG (Arg).

ΔΔGspecificity = ΔGSrc – ΔGGrb for a given peptide. All peptides except hAMII(Arg) (Kd = 102 ± 7 μM, ΔGCrk = −5.4 kcal mol−1), hAMII(gl-Trp) (Kd = 153 ± 9 μM, ΔGCrk = −5.2 kcal mol−1), and hAMII(gd-Trp) (Kd = 183 ± 11 μM, ΔGCrk = −5.1 kcal mol−1) bound poorly to Crk (Kd > 250 μM). All experiments were conducted in PBS at 25 °C.

Peptide affinity for target SH3 domain proteins was affected by replacement of Arg with arginine mimetic, with differential impact possible depending on the site (type I versus type II ligand), functional group (gGly, gVal, gPhe, or gTrp), stereochemistry (l- versus d-), and/or attachment (arginine versus homoarginine equivalent) of the arginine substitution. First considering type I mimics substituted on the Dap side chain (homoarginine equivalents, hAMI) (Table 1, Figure 5a-c), we observed, as expected, that loss of the polarity-determining arginine guanidinium resulted in a substantial loss of affinity (ΔΔGSrc = +1.7 kcal/mol, hAMI(Arg) versus hAMI(Dap-Ac) binding to Src; ΔΔGGrb = +1.4 kcal/mol, hAMI(Arg) versus hAMI(Dap-Ac) binding to Grb) (Figure 5a). In contrast, replacement of Arg with hArg(gGly) resulted in only a modest (ΔΔGSrc = +0.44 kcal/mol; ΔΔGGrb = +0.32 kcal/mol) loss in affinity, indicating that α-guanidino acids may substitute for Arg residues in peptides (Figure 5a). For peptides in this series, substitutions at the α-position to the guanidinium only modestly affected affinity for Src (Figure 5b). However, α-substitution more significantly affected affinity for Grb, in a manner highly dependent on the identity of the α-guanidino acid side chain and on its stereochemistry (Figure 5c). The hAMI peptides containing hArg(gd-Val), hArg(gd-Phe), and hArg(gd-Trp) substitution exhibited better specificity for Src over Grb (ΔΔGspecificity = −1.9, −2.0, and −1.5 kcal/mol, respectively) than the parent peptide (ΔΔGspecificity = −1.0 kcal/mol) or the glycine derivative (ΔΔGspecificity = −0.9 kcal/mol), indicating selection against binding to Grb when d-amino acid-based arginine mimetic peptides were employed. In contrast, the diastereomers hArg(gl-Phe) and hArg(gl-Trp) exhibited reduced specificity (ΔΔGspecificity = −0.7 and −0.5 kcal/mol, respectively), indicating that both the identity and stereochemistry of the α-substituted guanidinium significantly impacted target recognition and specificity.

In the series of arginine-equivalent peptides, in which substitution occurred on the Dap backbone nitrogen (AMI series), all arginine-mimetic peptides exhibited substantially reduced binding affinity for both Src and Grb (ΔΔGSrc = +1.3 to +1.8 kcal/mol, ΔΔGGrb = +0.8 to +1.6 kcal/mol) (Table 2) compared to the Arg-containing peptide. As was observed previously, replacement of Arg with a side chain lacking a guanidinium (AMI(Dap-Ac)) resulted in a substantial loss in Src affinity (ΔΔG = +1.6 kcal/mol). However, unexpectedly, in this case, and in contrast to the case with homoarginine-equivalent peptides, the arginine-mimetic peptide lacking a guanidium (AMI(Dap-Ac)) actually bound Src with an affinity similar to (or slightly better than) the analogous peptide with a guanidinium (AMI(gGly)) (ΔΔG = −0.1 kcal/mol). Analogous results were observed for binding to Grb, with the AMI(gGly) peptide binding with similar affinity as the peptide lacking a guanidinium (AMI(Dap-Ac)). For binding to both Src and Grb, the presence of an α-substituent on the α-guanidino acid in some case modestly increased binding compared to AMI(gGly), although in all cases binding was worse than observed in the hAMI series. The peptide AMI(gl-Phe) exhibited relative selectivity to Grb (ΔΔGspecificity = −0.5 kcal/mol, compared to ΔΔGspecificity = −1.0 kcal/mol for the parent peptide; ΔΔΔGspecificity = +0.5 kcal/mol), with a 0.7 kcal/mol increase in affinity for Grb compared to AMI(gGly), suggesting interaction of Grb with the α-guanidino acid side chain (Figure 5d). In total, these data suggest that in arginine-equivalent peptides, the guanidinium group is not readily able to interact favorably with the carboxylates in the SH3 domain, or alternatively that unfavorable interactions (e.g. with the amide group in the arginine mimetic, compared to the methylenes of an arginine) counteract favorable interactions with the guanidinium. In addition, this substitution is only readily incorporated at peptide termini due to the change in backbone structure (Figure 1). In sum, these data suggest that arginine-equivalent α-guanidino acids are functionally not readily able to substitute for arginine residues in molecular recognition within this peptide context.

Table 2.

Dissociation constants of type I arginine-equivalent arginine mimetic peptides (AMI).

|

Kd, μM |

Error | ΔG, kcal mol−1 |

ΔΔGaffinity, kcal mol−1 |

ΔΔGspecificity,b kcal mol−1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Src | Arg | 5.3 | 0.3 | −7.2 | 0 | −1.0 |

| Dap-Ac | 83 | 2.8 | −5.5 | 1.63 | −0.9 | |

| Arg(gGly) | 104 | 8.1 | −5.4 | 1.76 | −0.9 | |

| Arg(gl-Val) | 86 | 3.1 | −5.5 | 1.65 | −0.5 | |

| Arg(gd-Val) | 75 | 3.2 | −5.6 | 1.57 | −0.7 | |

| Arg(gl-Phe) | 54 | 4.8 | −5.8 | 1.37 | −0.5 | |

| Arg(gd-Phe) | 75 | 4.9 | −5.6 | 1.57 | −0.7 | |

| Arg(gl-Trp ) | 54 | 3.8 | −5.8 | 1.37 | −0.9 | |

| Arg(gd-Trp) | 51 | 3.6 | −5.8 | 1.34 | −1.1 | |

| Grb | Arg | 29 | 2 | −6.2 | 0 | |

| Dap-Ac | 388 | 75 | −4.6 | 1.53 | ||

| Arg(gGly) | 445 | 75 | −4.6 | 1.60 | ||

| Arg(gl-Val) | 210 | 21 | −5.0 | 1.17 | ||

| Arg(gd-Val) | 243 | 33 | −4.9 | 1.25 | ||

| Arg(gl-Phe) | 117 | 10 | −5.3 | 0.82 | ||

| Arg(gd-Phe) | 254 | 17 | −4.9 | 1.28 | ||

| Arg(gl-Trp) | 253 | 16 | −4.9 | 1.28 | ||

| Arg(gd-Trp) | 333 | 29 | −4.7 | 1.43 | ||

ΔΔGaffinity = ΔG (peptide) – ΔG (Arg).

ΔΔGspecificity = ΔGSrc – ΔGGrb for a given peptide. All peptides bound poorly to Crk (Kd > 250 μM). All experiments were conducted in PBS at 25 °C.

Replacement of arginine with α-guanidino acid arginine mimetics in type II SH3 domain peptide ligands (hAMII series peptides) resulted in significant modulation of protein affinity and specificity (Table 3), as was observed with type I homoarginine-equivalent ligands (hAMI). In the type II ligand series, the parent Arg-containing peptide bound preferentially to Grb over Src (ΔΔGspecificity = +0.7 kcal/mol). As expected, replacement of Arg with acetylated Dap resulted in a substantial loss of binding to both proteins. Interestingly, however, replacement of Arg with arginine mimetics resulted in a reversal of specificity in all cases, leading to a preference for binding to Src over binding to Grb, with ΔΔGspecificity = −0.4 to −1.0 kcal/mol, for an overall switch in target specificity from the parent peptide to the arginine-mimetic peptides ΔΔΔGspecificity = −1.1 to −1.6 kcal/mol (Figure 5e-f). The reversal of specificity was manifested almost entirely in selection against binding to Grb: all α-guanidino acid-containing peptides bound Grb with at least 10-fold worse affinity than the Arg peptide (ΔΔGGrb = +1.4 to +2.2 kcal/mol). In this series, there was only a modest preference in Src binding for l-amino acid-derived arginine mimetics compared to those derived from d-amino acids. Notably, the peptide hAMII(gD-Trp) exhibited enhanced overall affinity for Src compared to the Arg-containing peptide (ΔΔGSrc = −0.3 kcal/mol). This peptide also had the greatest specificity for Src over Grb (ΔΔGspecificity = −1.0 kcal/mol) among peptides in this series.

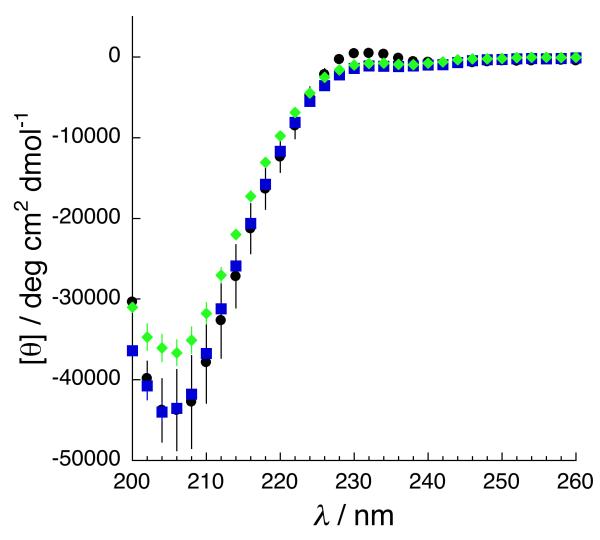

In order to confirm that the α-guanidino acid arginine mimetics were not globally changing the structure of the peptides, and thus impacting changes in affinity and specificity through a change in peptide structure, circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was conducted on the type II d-Trp arginine mimetic peptide (hAMII(gd-Trp), as well as on the guanidino-glycine derivative (hAMII(gGly)) and the parent arginine-containing peptide in this series (Figure 6). The CD spectra of all peptides exhibited maxima and minima at approximately 228 nm and 205 nm, respectively, indicative of polyproline II helix structure.[15] In addition, NMR data (Figure 4 and data not shown) reveal similar Hα and HN chemical shifts and 3JHNA coupling constants for all equivalent residues (other than conjugated Dap residues) in peptides within a given series. In combination, these data indicate that replacement of arginine with an α-guanidino acid-based arginine mimetic is minimally disruptive of peptide structure, and suggest that the effects of arginine mimetics observed above are more likely due to specific interactions with the target protein.[16]

Figure 6.

Circular dichroism spectra of representative peptides: squares, type II Arg peptide hAMII(Arg) (control, native peptide ligand); diamonds, type II gGly homoarginine-equivalent peptide (hAMII(gGly)); circles, type II gl-Trp homoarginine-equivalent arginine mimetic peptide (hAMII(gl-Trp)).

Discussion

We have developed an approach to stereospecifically synthesize peptides containing novel α-guanidino acid arginine mimetics. These arginine mimetics are derived from guanylation of α-amino acids and result in the placement of functional groups (i.e. amino acid side chains) and stereochemistry on the carbon adjacent to the guanidinium. The synthetic approach employs commercially available Fmoc-amino acids and thus allows the incorporation of a wide range of functionalities adjacent to the guanidinium, providing the possibility to increase target specificity and/or target affinity via a combination of functional groups for recognition and stereochemistry, and to disfavor binding to certain targets via unfavorable steric, electrostatic, hydrogen bonding, or other interactions. The reactions are all performed on solid phase using commercially available Fmoc amino acids. In this work, we employed one reagent, Moroder’s reactive benzotriazole-based guanylating reagent 1, that is not commercially available; 1 is readily prepared in one step from commercially available reagents (the intermediate compound bis(Boc)-thiourea is commercially available) or in two steps from inexpensive reagents (Scheme 1).[14a] This approach should also be readily applicable with other reactive guanylating reagents that can function for reactions on solid phase.[17]

In this work, we demonstrated the retention of stereochemistry in the solid phase synthesis of α-guaninido acid-containing molecules, via a two-stage deprotection that removes the guanidine Boc protecting group first and then subjects the peptide to standard peptide cleavage/deprotection conditions. Of note is the observation that coupled protected α-guanidino acids are prone to epimerization under acidic conditions, including those previously employed in low yield syntheses of diastereomeric small molecules containing α-guanidino acids.[7a, 7c, 7g] However, using the very mild guanidine Boc deprotection conditions developed herein of 6 M AcOH in MeCN, the stereochemical integrity of the α-guanidino acid was retained. Considering the reliance on readily available reagents and solid phase synthetic approaches, the methodology has broad potential application for the synthesis of stereochemically defined α-functionalized guanidiniums within peptides and small molecules and is a highly practical approach to synthesize peptides with arginine mimetics.

We examined the functional effects of α-guanidino acid-based arginine mimetics within the context of peptides for paralog-specific targeting of SH3 domains. Arginine mimetics were incorporated at the site of a critical polarity- and specificity-determining arginine residue at the N-terminus (type I ligand) or C-terminus (type II ligand) of the peptide. Two types of arginine mimetic were employed, one based on formal conjugation of the α-guanidino acid to the Dap side chain (generating a homoarginine equivalent, hAMI and hAMII series) and one based on formal conjugation to the Dap α-amino group main chain nitrogen (generating an arginine equivalent based on residue length, AMI series).

In the context of SH3 domain recognition, the arginine-equivalent arginine mimetic (AMI series), in which the peptide backbone structure is modified and thus is only suitable at peptide termini, was found to be inferior, leading to a reduction in SH3 domain affinity and no evidence that the guanidinium was able to participate in target recognition. Some peptides in this series exhibited a modest increase in preference for Grb over Src (ΔΔΔGspecificity up to +0.5 kcal/mol). The poor recognition characteristics of the arginine-equivalent α-guanidino acid-containing peptides could be due to the loss of hydrophobic interactions with the Arg methylenes, unfavorable interactions of the protein with the amide, or the loss in flexibility of the amide-containing side chain of the arginine mimetic preventing favorable interactions with the target, compared to the flexible hydrocarbon side chain in arginine.

In contrast, the homoarginine-equivalent arginine mimetic-containing peptides effectively induced specificity in SH3 domain recognition in a manner that was dependent on position (type I versus type II), stereochemistry, and side chain identity. In the type I peptides, all α-guanidino acid-containing peptides exhibited a modest loss in binding affinity for Src and Grb, while those with a d-amino acid-derived α-guanidino acid exhibited a more substantial loss in affinity for Grb. Thus, the (R)-α-guanidino acid-containing peptides all exhibited increased target specificity for Src over Grb compared to the native ligand, with the enhanced specificity achieved via selection against Grb. Negative selection is important to specific recognition. Indeed, native SH3 domains exhibit evidence of negative selection within the natural repertoire of ligands and SH3 domains.[18] This work provides a complementary strategy to achieve selection against alternative targets in guanidinium-mediated recognition.

Among type II SH3 domain ligands (hAMII), the native Arg-containing peptide bound preferentially to the Grb SH3 domain over the Src SH3 domain (ΔΔGspecificity = +0.66 kcal/mol). In contrast, all type II arginine-mimetic peptides preferentially bound Src over Grb, with specificities up to −0.95 kcal/mol, resulting in an overall reversal of SH3 domain specificity (ΔΔΔGspecificity = −1.1 to −1.6 kcal/mol) via the application of α-guanidino acid arginine mimetics. As was the case in type I (hAMI) ligands, the primary mechanism of modulated specificity was selection against Grb (ΔΔGGrb = +1.4 to +1.9 kcal/mol). Binding to Src was modestly affected by the stereochemistry and identity of the guanidino acid side chain (ΔΔGSrc = −0.3 to +0.7 kcal/mol), with (S) guanidino acid stereoisomers and tryptophan substitution leading to the highest Src affinity. Among the peptides examined, the tryptophan derivatives exhibited enhanced affinity for Src compared to the glycine derivative, indicative of a potentially favorable peptide side chain interaction with Src. In total, the results suggest that the employment of α-guanidino acid-based arginine mimetics is a strategy for achievement of paralog-specific SH3 domain recognition that is complementary to those previously described.[9f, 10]

Arginine residues and guanidiniums are widely employed in manners that exploit their unique molecular recognition properties. Examples where guanidinium groups are paramount or superior include specific recognition of RNA and DNA;[3a, 19]; intercellular communication via protein-protein interactions mediated by RGD motifs;[3b, 6, 20] polyarginine cell-penetrating peptides;[4] interactions with cell surface and intracellular sulfates and phosphates;[1a, 21] molecular recognition of bidentate anions by sensors;[1b, 2a, 2c, 2d, 22] Bronsted acid catalysis by guanidiniums;[2b, 7b, 23] intracellular signaling (including via SH3 domains and adaptor proteins);[8a, 10c, 24] and kinase substrate recognition,[25] among many other examples. In all of these cases, α-substitution of the guanidinium to introduce stereochemistry and functional groups could potentially lead to greater affinity and/or specificity in molecular recognition.[6]

Experimental Section

Peptide Synthesis

Peptides were synthesized using Rink amide resin on a PS3 peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies, Inc.) via standard Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis using HBTU as a coupling reagent. All peptides contained C-terminal amides. Homoarginine equivalent peptides (hArg(gXaa)) were acetylated on the N-terminus. Arginine equivalent peptides (Arg(gXaa)) were acetylated on the β-amino side chain of the diaminopropionic acid (Dap) residue.

Post-synthetic modification reactions were performed in capped disposable fritted columns (Image Molding, Inc.) with rotation on a Barnstead Thermoline Labquake rotary shaker. Mtt-protected Dap was selectively deprotected using 2% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/5% triethylsilane (TES) in CH2Cl2 (3 × 1 min). The resin was washed with CH2Cl2 (3×) and DMF (3×).

In order to synthesize the α-guanidino-acid containing peptides, Fmoc amino acids were coupled to Dap using standard solid phase peptide synthesis with HBTU as a coupling reagent (2 × 1 h). Fmoc removal was effected using 20% piperdine in DMF (3 × 5 min). Free amine groups were guanylated using a solution of 0.2 M N,N’-di-tert-butoxycarbonyl-1H-benzotriazole-1-carboxamidine (1) in DMF with slow shaking on a rotary shaker for 4-8 h, as judged for completion by cleavage and crude ESI-MS. Notably, this reaction proceeded to high conversions to the Dap-conjugated α-guanidino-acid without any added base. The solution was removed and the resin washed with CH2Cl2 (3×) and MeOH (3×).

Cleavage of the peptide from the resin and deprotection were achieved using a two-step protocol in order to minimize epimerization at the carbon α to the guanidine group. First, the Boc groups on the guanidine were removed using 6 M AcOH in MeCN (2 × 20 min). After removal of this solution, the resin was washed with CH2Cl2 (3×). Peptide cleavage and global deprotection was performed for 3 h using reagent K (84% TFA, 4% each of H2O, ethanedithiol, thioanisole, phenol). The solutions were concentrated by evaporation under nitrogen. After removal of most of the TFA by evaporation, the peptide was precipitated with ether and the precipitate dissolved in water.

Peptides were purified by reverse phase HPLC (Vydac semipreparative C18, 10 × 250 mm, 5 μm particle size, 300 Å pore). Peptides were purified to homogeneity using a linear gradient of 0-45% buffer B (20% water, 80% acetonitrile, 0.05% TFA) in buffer A (98% water, 2% acetonitrile, 0.05% TFA) over 60 minutes. Peptide purity was verified by reinjection on analytical HPLC (Varian Microsorb analytical C18, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, 300 Å pore). Peptides were characterized by ESI-MS (positive ion mode) on an LCQ Advantage (Finnigan) mass spectrometer. Expected and observed peptide masses were [M+H]+. Analytical data for the peptides: hAMI(Arg) (tR = 32.0 min, exp. 1429.7, obs. 1429.7); hAMI(Dap-Ac) (tR = 35.7 min, exp. 1403.7, obs. 1403.7); hAMI(gGly) (tR = 31.9 min, exp. 1461.1, obs. 1458.6); hAMI(gL-Val) (tR = 41.7 min, exp. 1502.8, obs. 1500.7); hAMI(gd-Val) (tR = 40.2, exp. 1502.8, obs. 1500.7); hAMI(gl-Phe) (tR = 45.8 min, exp. 1551.2, obs. 1548.7); hAMI(gd-Phe) (tR = 44.8 min, exp. 1551.2, obs. 1548.7); hAMI(gl-Trp) (tR = 45.7 min, exp. 1589.9, obs. 1587.6); hAMI(gd-Trp) (tR = 47.2 min, exp. 1589.9, obs. 1587.6); AMI(Dap-Ac) (tR = 48.0 min, exp. 1344.6, obs. 1344.5); AMI(gGly) (tR = 50.9 min, exp. 1401.7, obs. 1401.4); AMI(gl-Val) (tR = 50.6 min, exp. 1443.7, obs. 1443.6); AMI(gd-Val) (tR = 52.6 min, exp. 1443.7, obs. 1443.6); AMI(gl-Phe) (tR = 55.2 min, exp. 1491.8, obs. 1491.5); AMI(gd-Phe) (tR = 57.2 min, exp. 1491.8, obs. 1491.4); AMI(gl-Trp) (tR = 54.5 min, exp. 1530.8, obs. 1530.4); AMI(gd-Trp) (tR = 51.6 min, exp. 1530.8, obs. 1530.4); hAMII(Arg) (tR = 34.1 min, exp. 1461.7, obs. 1461.6); hAMII(Dap-Ac) (tR = 43.1 min, exp. 1433.7, obs. 1433.5); hAMII(gGly) (tR = 38.1 min, exp. 1490.7, obs. 1490.7); hAMII(gl-Val) (tR = 41.0 min, exp. 1532.8, obs. 1532.7); hAMII(gd-Val) (tR = 39.9 min, exp. 1532.8, obs. 1532.6); hAMII(gl-Phe) (tR = 45.1 min, exp. 1580.8, obs. 1580.6); hAMII(gd-Phe) (tR = 45.2 min, exp. 1580.8, obs. 1580.5); hAMII(gl-Trp) (tR = 41.7 min, exp. 1619.9, obs. 1619.6); hAMII(gd-Trp) (tR = 40.0 min, exp. 1619.9, obs. 1619.7).

N,N’-di-tert-butoxycarbonyl-1H-benzotriazole-1-carboxamidine (1)

To a solution of benzotriazole (0.70 g, 5.8 mmol) in anhydrous DMF were added N,N’-bis(t-butoxycarbonyl)thiourea[14b] (0.94 g, 3.4 mmol) and diisopropylethylamine (2.68 mL, 16.5 mmol). After 2 minutes, EDCI (0.95 g, 5.0 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture and the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 4 hours at room temperature. The DMF was evaporated under vacuum and the solid dissolved in ethyl acetate (30 mL). The ethyl acetate layer was washed with water, 5% NaHCO3, water, and brine (6 mL each); dried over sodium sulfate; and concentrated by rotary evaporation. Purification (SiO2, 80:20 hexanes:EtOAc) yielded a white solid (0.72 g, 56%) whose NMR spectra correlated to literature data.[14a]

Fluorescein Labeling of Peptides

Lyophilized peptides were dissolved in 100 mM NaHCO3 buffer (pH 10.0, 200 μL). 5-fluorescein isothiocyanate (isomer I) (200 μL of a 10 mg/mL solution in DMF) was added over 2 minutes to the peptide solution with gentle vortexing. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 1-2 hours at room temperature. The solution was filtered and the pH adjusted with 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5. Peptides were purified to homogeneity by reverse phase HPLC (Vydac semipreparative C18, 10 × 250 mm, 5 μm particle size, 300 Å pore) using a linear gradient of 15-65% buffer B in buffer A over 60 minutes. Peptide purity was verified by reinjection on analytical HPLC (Varian Microsorb analytical C18, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, 300 Å pore). Peptides were characterized by ESI-MS (positive ion mode) on an LCQ Advantage (Finnigan) mass spectrometer. Analytical data for the peptides: hAMI(Arg) (tR = 33.6 min, exp. 1819.1, obs. 1819.7); hAMI(Dap-Ac) (tR = 33.8 min, exp. 1793.1, obs. 1792.6); hAMI(gGly) (tR = 42.7 min, exp. 1850.5, obs. 1848.6); hAMI(gl-Val) (tR = 41.2 min, exp. 1892.2, obs. 1890.7); hAMI(gd-Val) (tR = 40.2 min, exp. 1892.2, obs. 1890.7); hAMI(gl-Phe) (tR = 40.1 min, exp. 1940.6, obs. 1939.6); hAMI(gd-Phe) (tR = 39.7 min, exp. 1940.6, obs. 1939.6); hAMI(gl-Trp) (tR = 43.0 min, exp. 1979.3, obs. 1977.5); hAMI(gd-Trp) (tR = 42.5 min, exp. 1979.3, obs. 1977.5); AMI(Dap-Ac) (tR = 42.2 min, exp. 1734.0, obs. 1734.5); AMI(gGly) (tR = 42.2 min, exp. 1791.0, obs. 1791.4); AMI(gl-Val) (tR = 45.5 min, exp. 1833.1, obs. 1833.4); AMI(gd-Val) (tR = 44.7 min, exp. 1833.1, obs. 1832.3); AMI(gl-Phe) (tR = 49.0 min, exp. 1881.2, obs. 1881.2); AMI(gd-Phe) (tR = 52.7 min, exp. 1881.2, obs. 1880.3); AMI(gl-Trp) (tR = 52.6 min, exp. 1920.3, obs.1920.3); AMI(gd-Trp) (tR = 53.7 min, exp. 1920.2, obs. 1920.3); hAMII(Arg) (tR = 35.5 min, exp. 1849.9, obs. 1850.4); hAMII(Dap-Ac) (tR = 37.2 min, exp. 1823.0, obs. 1823.4); hAMII(gGly) (tR = 36.0 min, exp. 1880.1, obs. 1880.6); hAMII(gl-Val) (tR = 38.3 min, exp. 1922.2, obs. 1921.5); hAMII(gd-Val) (tR = 38.2 min, exp. 1922.2, obs. 1922.5); hAMII(gl-Phe) (tR = 41.7 min, exp. 1970.2, obs. 1969.5); hAMII(gd-Phe) (tR = 40.7 min, exp. 1970.2, obs. 1970.5); hAMII(gl-Trp) (tR = 42.2 min, exp. 2009.2, obs. 2009.4); hAMII(gd-Trp) (tR = 43.1 min, exp. 2009.2, obs. 2009.5).

Protein Expression and Purification

Plasmids containing the coding regions for the Src (residues 87-148), nGrb2 (1-64) and Crk (134-190) SH3 domains were obtained from the lab of Wendell Lim.[10a, 10b] Plasmids encoded both a carboxy-terminal hexahistidine and an amino-terminal glutathione S-transferase. BL21(DE3) pLysS competent cells (EMD Biosciences) were transformed with the plasmids and incubated on ampicillin plates overnight. Single colonies were incubated into overnight cultures (100 mL) of luria broth with shaking at 37 °C. These cultures were seeded into cultures (1 L) of terrific broth (BD Diagnostic Systems). Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG added at an OD600 = 0.6-0.8, and the cells incubated for 1.5-5 h at 37 °C. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation, the supernatant removed, and the pellets stored at −20 °C until purification. Bacterial pellets were suspended in His-Tag binding buffer (50 mL of 500 mM NaCl, 40 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.9) and lysed by sonication, and the pellets cleared by centrifugation. Protein was purified via His-Tag resin (EMD Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Protein eluents were dialyzed into phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4 containing 5 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (5 × 10 min) using a Spectra/Por 6 membrane, MWCO 10,000 (Spectrum Laboratories). Protein size and purity were verified via SDS-PAGE. Bradford assays (BioRad) were used to determine protein concentrations.

SH3 domain-peptide fluorescence polarization binding assays

For fluorescence polarization assays, proteins and fluorescein-labeled ligands were diluted in 1× PBS (140 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.4) containing 0.1 mM DTT and 0.04 mg/mL BSA (BioRad). Concentrations of peptides were determined based on fluorescein absorbance (ε = 77,000 M−1 cm−1 at 495 nm). Two-fold serial dilutions of Src, nGrb2, and Crk proteins, ranging from 360 μM to 2.7 nM, were mixed with peptides (100 nM), BSA (0.04 mg/mL), and DTT (100 μM) (final concentrations) in 96-well flat bottom black opaque plates (Costar) at 200 μL per well. Individual trials on a protein with l- and d- guanidino acid-containing peptides of a given side-chain were conducted with a single serial dilution to ensure that any differences observed could be ascribed to stereochemistry. After 15 minutes equilibration at room temperature, plates were read on a Perkin Elmer Fusion plate reader in fluorescence polarization mode with a 485 nm fluorescein excitation filter and a 535 nm emission filter with polarizer. Data points were the average of at least three independent trials. Polarization data are in millipolarization units. Error bars indicate standard error.

The data were fit to equation 1 using a non-linear least squares fitting algorithm (Kaleidagraph version 4.0, Synergy Software), where Pol = polarization, Polmin = polarization in the absence of protein, Polmax = polarization at saturation, Pt = total protein concentration, Kd = dissociation constant of the peptide-protein complex, and [lig]t = total peptide concentration (0.1 μM). The data were fit to calculate Polmax and Kd.

| (1) |

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy was conducted to verify that no epimerization occurred during peptide synthesis, cleavage and global deprotection, and purification. Solutions contained 5 mM deuteratured sodium acetate (pH 4.0), 10 mM (hAMI series) or 100 mM (AMI and hAMII series) NaCl, 150 μM TSP[D4] and 90% H2O/10% D2O, with final peptide concentrations of 70 μM – 1.5 mM. NMR spectra were recorded at 296 K on a Brüker AVC 600 MHz NMR spectrometer with a cryoprobe. 1-D and TOCSY spectra were collected with water suppression using a Watergate pulse sequence. 1-D spectra were collected with a sweep width of 6009 Hz or 7183 Hz; 8192 or 16384 data points; and a relaxation delay of 2-3 s. TOCSY spectra were collected with sweep widths of 7183 Hz in t1 and t2, 512-600 × 4096 complex data points, 2-4 scans per increment, and a relaxation delay of 2 s.

Circular Dichroism

Solutions contained 5 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 25 mM KF, and 100 μM peptide. CD spectra were collected at 25 °C on a Jasco J-810 Spectropolarimeter in a 2 mm quartz cell (Starna). Data were collected every 2 nm with an averaging time of 4 s, 2 accumulations, and a 2 nm bandwidth. Data were baseline corrected but were not smoothed. Data points were the average of at least three independent trials. Error bars indicate standard error.

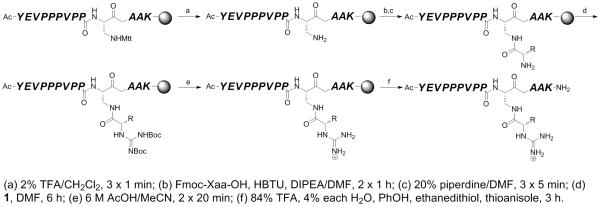

Figure 3.

Sequences of type I and type II SH3 domain ligand peptides. The proline-rich (PXXP-containing) core sequence is indicated in blue. The core sequence and Arg residues of the type I ligand are from the VSL12 protein (residues 76-82) observed bound to the Src SH3 domain (PDB 1qwf).[11a, 11d, 12] The type II ligand peptide is derived from the mSOS protein observed in the SEM-5 (Grb2 homologue) SH3 domain complex (PDB 1sem).[11c] The specificity- and polarity-determining arginine residue is indicated in red. The indicated Arg was replaced with diaminopropionic acid (Dap) for arginine mimetic-containing peptides. All peptides were acetylated on either the N-terminus (homoarginine equivalents, hArg(gXaa)) or on the Dap side chain (arginine equivalents, Arg(gXaa)). Peptides containing type I arginine equivalents (i.e. Arg(gXaa)) lacked the N-terminal Gly. The guanidino acid was conjugated via the Dap side chain (homoarginine equivalents, hAMI and hAMII) or the N-terminus (arginine equivalents, AMI). For fluorescence polarization experiments, peptides were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) on the side chain of the C-terminal lysine. All peptides contained C-terminal amides.

Acknowledgements

We thank Susan Carr Zondlo for the development of protein expression and purification protocols and for the development of direct binding assays of fluorescein-labeled peptides for SH3 domain-containing proteins. We thank Wendell Lim for providing us with plasmids encoding the Src, Grb, and Crk SH3 domains. We thank Richard Borch for helpful discussion. We thank NIH (1P20 RR17716) (COBRE), NSF (CAREER, CHE-0547973), and the University of Delaware for partial support of this work.

References

- [1] a).Schug KA, Lindner W. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:67–113. doi: 10.1021/cr040603j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Orner BP, Hamilton AD. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2001;41:141–147. [Google Scholar]; c) Berlinck RGS, Burtoloso ACB, Trindade-Silva AE, Romminger S, Morais RP, Bandeira K, Mizuno CM. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:1871–1907. doi: 10.1039/c0np00016g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Berlinck RGS, Burtoloso ACB, Kossuga MH. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008;25:919–954. doi: 10.1039/b507874c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2] a).Best MD, Tobey SL, Anslyn EV. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003;240:3–15. [Google Scholar]; b) Leow D, Tan CH. Chem. Asian J. 2009;4:488–507. doi: 10.1002/asia.200800361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Blondeau P, Segura M, Pérez-Fernández R, de Mendoza J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:198–210. doi: 10.1039/b603089k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Schmuck C. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006;250:3053–3067. [Google Scholar]

- [3] a).Battiste JL, Mao HY, Rao NS, Tan RY, Muhandiram DR, Kay LE, Frankel AD, Williamson JR. Science. 1996;273:1547–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ruoslahti E. Ann. Rev. Cell Devel. Biol. 1996;12:697–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4] a).Schmidt N, Mishra A, Lai GH, Wong GCL. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1806–1813. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wender PA, Galliher WC, Goun EA, Jones LR, Pillow TH. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2008;60:452–472. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Potocky TB, Silvius J, Menon AK, Gellman SH. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:917–926. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5] a).Chakrabarti P. Int. J. Pept. Prot. Res. 1994;43:284–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1994.tb00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dunbrack RL, Jr., Karplus M. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;230:543–574. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lovell SC, Word JM, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Proteins. 2000;40:389–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Peterlin-Masic L, Kikelj D. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:7073–7105. [Google Scholar]

- [7] a).Balakrishnan S, Zhao C, Zondlo NJ. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:9834–9837. doi: 10.1021/jo701766c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yu ZP, Liu XH, Zhou L, Lin LL, Feng XM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5195–5198. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Suhs T, König B. Chem.-Eur. J. 2006;12:8150–8157. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Thanos CD, Randal M, Wells JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15280–15281. doi: 10.1021/ja0382617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Arkin MR, Randal M, DeLano WL, Hyde J, Luong TN, Oslob JD, Raphael DR, Taylor L, Wang J, McDowell RS, Wells JA, Braisted AC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1603–1608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252756299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Braisted AC, Oslob JD, Delano WL, Hyde J, McDowell RS, Waal N, Yu C, Arkin MR, Raimundo BC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:3714–3715. doi: 10.1021/ja034247i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Raimunddo BC, Oslob JD, Braisted AC, Hyde J, McDowell RS, Randal M, Waal N, Wilkinson J, Yu CH, Arkin MR. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:3111–3130. doi: 10.1021/jm049967u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Thanos CD, DeLano WL, Wells JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:15422–15427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607058103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Rowley GL, Greenleaf AL, Kenyon GL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:5542–5551. doi: 10.1021/ja00750a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Miller AE, Bischoff JJ. Synthesis. 1986:777–779. [Google Scholar]; k) Jursic BS, Neumann D, McPherson A. Synthesis. 2000:1656–1658. [Google Scholar]; l) Siemion IZ, Gawlowska M, Slepokura K, Biernat M, Wieczorek Z. Peptides. 2005;26:1543–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Poss MA, Iwanowicz E, Reid JA, Lin J, Gu ZX. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:5933–5936. [Google Scholar]; n) Drake B, Patek M, Lebl M. Synthesis. 1994:579–582. [Google Scholar]; o) Lal B, Gangopadhyay AK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:2483–2486. [Google Scholar]; p) Yong YF, Kowalski JA, Lipton MA. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:1540–1542. [Google Scholar]; q) Yong YF, Kowalski JA, Thoen JC, Lipton MA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- [8] a).Zarrinpar A, Bhattacharyya RP, Lim WA. Sci. STKE. 2003;2003:re8. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.179.re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Musacchio A. Protein Modules and Protein-Protein Interactions. 2003;Vol. 61:211–268. [Google Scholar]; c) Macias MJ, Wiesner S, Sudol M. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:30–37. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kay BK, Williamson MP, Sudol P. FASEB J. 2000;14:231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9] a).Smithgall TE. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 1995;34:125–132. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(95)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dalgarno DC, Botfield MC, Rickles RJ. Biopolymers. 1997;43:383–400. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)43:5<383::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Vidal M, Gigoux V, Garbay C. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2001;40:175–186. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Rickles RJ, Botfield MC, Zhou X-M, Henry PA, Brugge JS, Zoller MJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:10909–10913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Cobos ES, Pisabarro MT, Vega MC, Lacroix E, Serrano L, Ruiz-Sanz J, Martinez JC. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;342:355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Li SSC. Biochem. J. 2005;390:641–653. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Zellefrow CD, Griffiths JS, Saha S, Hodges AM, Goodman JL, Paulk J, Kritzer JA, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16506–16507. doi: 10.1021/ja0672977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10] a).Nguyen JT, Turck CW, Cohen FE, Zuckerman RN, Lim WA. Science. 1998;282:2088–2092. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nguyen JT, Porter M, Amoui M, Miller WT, Zuckermann RN, Lim WA. Chem. Biol. 2000;7:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bedford MT, Frankel A, Yaffe MB, Clarke S, Leder P, Richard S. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:16030–16036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909368199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Cesareni G, Panni S, Nardelli G, Castagnoli L. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Fernandez-Ballester G, Blanes-Mira C, Serrano L. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:619–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11] a).Feng SB, Chen JK, Yu HT, Simon JA, Schreiber SL. Science. 1994;266:1241–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.7526465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yu H, Chen JK, Feng S, Dalgarno DC, Brauer AW, Schreiber SL. Cell. 1994;76:933–945. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lim WA, Richards FM, Fox RO. Nature. 1994;372:375–379. doi: 10.1038/372375a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Feng S, Kasahara C, Rickles RJ, Schreiber SL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:12408–12415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yu HT, Chen JK, Feng SB, Dalgarno DC, Brauer AW, Schreiber SL. Cell. 1994;76:933–945. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McDonald CB, Seldeen KL, Deegan BJ, Farooq A. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4074–4085. doi: 10.1021/bi802291y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14] a).Musiol HJ, Moroder L. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3859–3861. doi: 10.1021/ol010191q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Iwanowicz EJ, Poss MA, Lin J. Synth. Commun. 1993;23:1443–1445. [Google Scholar]

- [15] a).Woody RW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8234–8245. doi: 10.1021/ja901218m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sreerama N, Woody RW. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10022–10025. doi: 10.1021/bi00199a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Rucker AL, Pager CT, Campbell MN, Qualls JE, Creamer TP. Proteins. 2003;53:68–75. doi: 10.1002/prot.10477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kelly MA, Chellgren BW, Rucker AL, Troutman JM, Fried MG, Miller AF, Creamer TP. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14376–14383. doi: 10.1021/bi011043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Shi Z, Chen K, Liu Z, Ng A, Bracken WC, Kallenbach NR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17964–17968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507124102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Ding L, Chen K, Santini PA, Shi Z, Kallenbach NR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8092–8093. doi: 10.1021/ja035551e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Shi ZS, Olson CA, Rose GD, Baldwin RL, Kallenbach NR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9190–9195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112193999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lam SL, Hsu VL. Biopolymers. 2003;69:270–281. doi: 10.1002/bip.10354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Katritzky AR, Rogovoy BV. Arkivoc. 2005;(iv):49–87. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zarrinpar A, Park SH, Lim WA. Nature. 2003;426:676–680. doi: 10.1038/nature02178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19] a).Ellenberger TE, Brandl CJ, Struhl K, Harrison SC. Cell. 1992;71:1223–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Luedtke NW, Baker TJ, Goodman M, Tor Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:12035–12036. [Google Scholar]; c) Xuereb H, Maletic M, Gildersleeve J, Pelczer I, Kahne D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:1883–1890. [Google Scholar]; d) Puglisi JD, Chen L, Blanchard S, Frankel AD. Science. 1995;270:1200–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Bailly C, Arafa RK, Tanious FA, Laine W, Tardy C, Lansiaux A, Colson P, Boykin DW, Wilson WD. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1941–1952. doi: 10.1021/bi047983n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Zondlo NJ, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:6938–6939. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Galler KM, Aulisa L, Regan KR, D’Souza RN, Hartgerink JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3217–3223. doi: 10.1021/ja910481t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Colvin RA, Campanella GSV, Manice LA, Luster AD. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:5838–5849. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00556-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22] a).Kneeland DM, Ariga K, Lynch VM, Huang CY, Anslyn EV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:10042–10055. [Google Scholar]; b) Albert JS, Goodman MS, Hamilton AD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:1143–1144. [Google Scholar]; c) Peczuh MW, Hamilton AD, SanchezQuesada J, deMendoza J, Haack T, Giralt E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:9327–9328. [Google Scholar]; d) Tobey SL, Anslyn EV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14807–14815. doi: 10.1021/ja030507k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Echavarren A, Galán A, Lehn J-M, de Mendoza J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:4994–4995. [Google Scholar]

- [23] a).Piatek AM, Gray M, Anslyn EV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9878–9879. doi: 10.1021/ja046894v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ait-Haddou H, Sumaoka J, Wiskur SL, Folmer-Andersen JF, Anslyn EV. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:4014–4016. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021104)41:21<4013::AID-ANIE4013>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lovick HM, Michael FE. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1016–1019. [Google Scholar]; d) Sohtome Y, Hashimoto Y, Nagasawa K. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:2894–2897. [Google Scholar]; e) Terada M, Ube H, Yaguchi Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128 doi: 10.1021/ja057848d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Terada M, Nakano M, Ube H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16044–16045. doi: 10.1021/ja066808m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Ishikawa T, Kumamoto T. Synthesis. 2006:737–752. [Google Scholar]; h) Uyeda C, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9228–9229. doi: 10.1021/ja803370x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Fu X, Loh W-T, Zhang Y, Chen T, Ma T, Liu H, Wang J, Tan C-H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7387–7390. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Leow D, Tan C-H. Synlett. 2010:1589–1605. [Google Scholar]; k) Fu X, Tan C-H. Chem. Comm. 2011;47:8210–8222. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03691a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Uyeda C, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5062–5075. doi: 10.1021/ja110842s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Corey EJ, Grogan MJ. Org. Lett. 1999;1:157–160. doi: 10.1021/ol990623l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24] a).Pawson T, Nash P. Genes & Development. 2000;14:1027–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bedford MT, Sarbassova D, Xu J, Leder P, Yaffe MB. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:10359–10369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25] a).Songyang Z, Blechner S, Hoagland N, Hoekstra MF, Piwnica-Worms H, Cantley LC. Curr. Biol. 1994;4:973–982. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hutti JE, Jarrell ET, Chang JD, Abbott DW, Storz P, Toker A, Cantley LC, Turk BE. Nat. Methods. 2004;1:27–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Mok J, Kim PM, Lam HYK, Piccirillo S, Zhou XQ, Jeschke GR, Sheridan DL, Parker SA, Desai V, Jwa M, Cameroni E, Niu HY, Good M, Remenyi A, Ma JLN, Sheu YJ, Sassi HE, Sopko R, Chan CSM, De Virgilio C, Hollingsworth NM, Lim WA, Stern DF, Stillman B, Andrews BJ, Gerstein MB, Snyder M, Turk BE. Science Signaling. 2010;3 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]