Abstract

It is likely that patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have a limited understanding of their illness. Here we studied the relationships between objective and perceived knowledge in CKD using the Kidney Disease Knowledge Survey and the Perceived Kidney Disease Knowledge Survey. We quantified perceived and objective knowledge in 399 patients at all stages of non-dialysis dependent CKD. Demographically, the patient median age was 58 years, 47% were women, 77% had stages 3-5 CKD, and 83% were Caucasians. The overall median score of the perceived knowledge survey was 2.56 (range: 1-4), and this new measure exhibited excellent reliability and construct validity. In unadjusted analysis, perceived knowledge was associated with patient characteristics defined a priori, including objective knowledge and patient satisfaction with physician communication. In adjusted analysis, older age, male gender, and limited health literacy were associated with lower perceived knowledge. Additional analysis revealed that perceived knowledge was associated with significantly higher odds (2.13), and objective knowledge with lower odds (0.91), of patient satisfaction with physician communication. Thus, our results present a mechanism to evaluate distinct forms of patient kidney knowledge, and identify specific opportunities for education tailored to patients with CKD.

Keywords: Patient knowledge, kidney disease, health literacy, perceived knowledge, objective knowledge

INTRODUCTION

Educating patients about chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an essential component of comprehensive predialysis care,1-4 and is linked to improved clinical outcomes. In patients who are near renal replacement therapy, educational interventions increase patient disease and treatment knowledge, delay initiation of dialysis, and extend survival.5-7 In end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients, more disease knowledge is associated with increased use of preferred hemodialysis access types,8 and increased participation in self-management behaviors.9

Studies that have descriptively examined patient kidney disease knowledge of patients are useful because they identify areas of low knowledge and inform educational interventions. However, studies vary in the types of knowledge measured. Some focus on patients’ perceptions of what they know about kidney disease (perceived knowledge),10,11 and others examine what patients actually know (objective knowledge).5,9,12-14 Conclusions about the effect that low knowledge has on outcomes often imply that these two measures of knowledge are the same—most often assuming perceived knowledge sufficiently represents actual knowledge. But the extent of the relationship between perceived and objective CKD knowledge is unclear, and research indicates the impact of different types of knowledge on behaviors15 and patient outcomes,16 may vary.

In addition, little information is available describing the specific impact that provider communication has on either type of patient kidney disease knowledge. Recent data examining audio recordings between primary care providers and patients at risk for CKD reveal that discussion rarely focuses on the topic of kidney disease.17 The findings suggest low patient awareness and knowledge about CKD are due, at least in part, to lack of specific provider communication on the topic. When effective communication does occur, however, it significantly increases patient knowledge about medication risks18 and treatment benefits.19 Furthermore, effective patient-provider communication influences patient satisfaction with care,20 which significantly contributes to treatment adherence.21

In patients with kidney disease unanswered questions remain about types of knowledge important to patient outcomes, and the relationship of knowledge to patient satisfaction with provider communication. This cross-sectional study captured concurrent measures of patient knowledge and patient satisfaction. The aim of the study was to develop and validate a measure of perceived knowledge in patients with CKD who are not yet receiving renal replacement therapy. We then examined our measure of patient perceived knowledge for associations with objective kidney knowledge and patient satisfaction with their provider’s interpersonal and communication skills. We hypothesized that perceived knowledge would be low in patients with CKD, but that higher perceived knowledge would be associated with higher objective knowledge and more satisfaction with provider communication.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Of 604 patients asked to participate, 406 agreed to take the Perceived Kidney Disease Knowledge survey, that is, PiKS (67% response rate). Sex and age data on the nonresponders were available, and there were no differences in these demographics compared with responders. Of the 406 participants enrolled, five withdrew for the following reasons: illness (2 patients), patient did not have time (2 patients), and 1 patient did not want to finish. Of the 401 remaining patients, 399 answered ≥ 7 of the 9 perceived knowledge items, and were included in the final analysis. The patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | N | median (IQR) or n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 399 | 58(46, 67) |

| Sex | 399 | |

| Female | 187 (47%) | |

| Male | 212 (53%) | |

| Education | 399 | |

| High School and greater | 374 (94%) | |

| Less than High School | 25 (6%) | |

| Race | 399 | |

| Non-White | 68 (17%) | |

| White | 331 (83%) | |

| Average eGFR£, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 399 | 41(28, 57) |

| Stage of CKD | 399 | |

| CKD stages 1-2 | 92 (23%) | |

| CKD stage 3 | 194 (49%) | |

| CKD stages 4-5 | 113 (28%) | |

| Number of kidney doctor visits past one year | 399 | |

| ≤ 2 visits | 168 (42%) | |

| ≥ 3 visits | 231 (58%) | |

| Income, in thousands per year | 379 | |

| ≤ $25,000 | 70 (18%) | |

| $25,001 - $55,000 | 128 (34%) | |

| > $55,000 | 181 (48%) | |

| Know someone with CKD | 397 | |

| No | 196 (49%) | |

| Yes | 201 (51%) | |

| Attending code | 399 | |

| 1 | 113 (28%) | |

| 2 | 71 (18%) | |

| 3 | 126 (32%) | |

| 4 | 46 (12%) | |

| 5 | 43 (11%) | |

| Health Literacy | 399 | |

| ≥ 9th grade level | 328 (82%) | |

| < 9th grade level | 71 (18%) | |

| Attendance in kidney education class | 399 | |

| Did attend a class | 67 (17%) | |

| Did not attend a class | 332 (83%) | |

| Awareness of kidney problem | 399 | |

| Not aware | 26 (7%) | |

| Aware | 373 (93%) | |

| Awareness of CKD Diagnosis | 399 | |

| Not aware | 122 (31%) | |

| Aware | 277 (69%) | |

| Perceived Kidney Knowledge summary score (On scale of: 1-4) | 399 | 2.56 (2.11, 3.00) |

| Kidney Knowledge score (% total correct) | 399 | 68% (57, 75) |

| Provider communication satisfaction summary score (On scale of: 1-5) |

398 | 5(4.51, 5.00) |

| Provider communication satisfaction responses: | 398 | |

| All excellent ratings | 221 (56%) | |

| Not all excellent ratings | 177 (44%) |

Perceived Kidney Knowledge Survey (PiKS)

Factor analysis revealed one underlying subscale for PiKS (Eigen value = 4.9) with the factor loadings ranging from 0.63 to 0.84. This means that PiKS variation was primarily accounted for by one underlying construct which we defined as “perceived kidney disease knowledge.” We further evaluated the PiKS for internal consistency and found the reliability coefficient (alpha) was 0.91, considered in the range of excellent.22 The median (IQR) of PiKS score was 2.56 (2.11, 3.00).

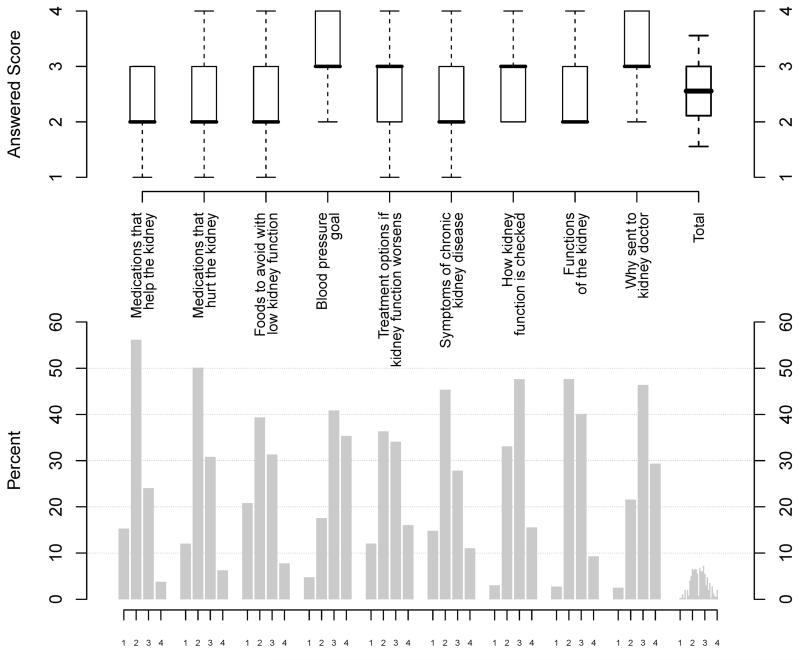

Table 2 lists responses to individual PiKS items. The majority of participants felt they had a “good amount” or “a lot” of knowledge about why they were sent to a kidney doctor (75%), how kidney function is checked by a doctor (64%), and their goal blood pressure (77%). More than 50% of the participants reported they had little or no knowledge about medications that help the kidney (72%), medications that hurt the kidney (63%), foods that should be avoided in case of low kidney function (61%), symptoms of chronic kidney disease (61%), and functions of the kidney (51%). Additional details showing box plots and frequencies of the responses for each PiKS item are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Perceived Kidney Disease Knowledge Survey item responses

| Perceived Kidney Knowledge Survey Item | N | n (%) of patients reporting little or no knowledge |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of medications that help the kidney | 396 | 285 (72%) |

| Knowledge of medications that can hurt the kidney | 396 | 248 (63%) |

| Knowledge of foods to avoid if kidney function is low | 396 | 240 (61%) |

| Knowledge of blood pressure goal | 393 | 89 (23%) |

| Knowledge of treatment options if kidney function gets worse |

393 | 193 (49%) |

| Knowledge of symptoms of chronic kidney disease | 395 | 240 (61%) |

| Knowledge of how kidney function is checked | 396 | 144 (36%) |

| Knowledge of the functions of the kidney | 398 | 201 (51%) |

| Knowledge of why patient was sent to a kidney doctor | 398 | 96 (25%) |

N indicates the number of nonmissing values

Figure 1.

Graphical summary of perceived knowledge--itemized and overall.

The upper graph presents box plots (median in bold line and interquartile range as top and bottom of box) for each Perceived Kidney Disease Knowledge Surve (PiKS) question, with a box plot of the total PiKS summary score at the far right. The box and whisker plots present 0.05 and 0.95 percentiles. The bottom graph presents frequencies of each possible response (1,2,3,or 4) for each PiKS question, with the rightmost distribution representing the distribution of total PiKS survey scores.

Associations with perceived kidney knowledge

Table 3 shows the unadjusted associations of PiKS summary score with participant characteristics including objective knowledge and patient satisfaction with provider communication. Increasing age was significantly associated with decreasing perceived knowledge (Spearman correlation −0.17, p<0.001). Women had higher PiKS scores than men (median (IQR) 2.67 (2.22, 3.11) for women vs. 2.44 (2.00, 2.89) for men; p=0.006). In addition, PiKS score was significantly associated with income, education, health literacy, attending code, knowing someone with kidney disease, awareness of kidney problem, attendance in kidney education class, average eGFR, and CKD stage. Perceived knowledge was also associated with objective knowledge (Kidney Disease Knowledge Survey (KiKS); Spearman correlation 0.32; p<0.0001), as well as satisfaction with provider communication (Communication Assessment Tool (CAT); 0.15; p=0.003). Neither race nor number of doctor visits were associated with overall perceived knowledge.

Table 3.

Unadjusted associations between PiKS and patient characteristics, including KiKS, and CAT

| Characteristics - categorical | PiKS Median (IQR) Score | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.006 | |

| Male | 2.44(2.00, 2.89) | |

| Female | 2.67(2.22, 3.11) | |

| Race | 0.89 | |

| Non-White | 2.59 (2.22, 2.89) | |

| White | 2.56 (2.11, 3.00) | |

| Attending Code | 0.017 | |

| 1 | 2.44 (2.22, 2.89) | |

| 2 | 2.25 (2.00, 2.87) | |

| 3 | 2.63 (2.22, 3.11) | |

| 4 | 2.59 (2.11, 2.89) | |

| 5 | 2.89 (2.28, 3.06) | |

| Know someone with CKD? | <0.0001 | |

| No | 2.33 (2.00, 2.80) | |

| Yes | 2.67 (2.22, 3.11) | |

| Aware of kidney problem? | <0.001 | |

| No | 2.22 (1.89, 2.49) | |

| Yes | 2.56 (2.11, 3.00) | |

| Aware of “Chronic Kidney Disease?” | <0.0001 | |

| No | 2.22 (1.89, 2.62) | |

| Yes | 2.67 (2.22, 3.11) | |

| Education | 0.027 | |

| < High School | 2.33 (2.00, 2.67) | |

| ≥ High School | 2.56 (2.11, 3.00) | |

| Number of kidney doctor visits past one year | 0.081 | |

| ≤ 2 | 2.44 (2.47, 3.44) | |

| > 2 | 2.56 (2.12, 3.00) | |

| Attendance in kidney education class | <0.0001 | |

| Yes | 2.89 (2.47, 3.44) | |

| No | 2.44 (2.11, 2.89) |

| Characteristics – continuous / ordinal | Spearman’s Correlation | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | −0.17 | <0.001 |

| Average eGFR£, mL/min/1.73 m2 | −0.14 | 0.005 |

| CKD (stages 1-2, 3, and 4-5) | 0.11 | 0.031 |

| Income (<$25,000, $25,000-55,000, and >$55,000) | 0.17 | 0.001 |

| Health Literacy (REALM) | 0.19 | <0.0001 |

| Kidney Knowledge Survey (KiKS) Score | 0.32 | <0.0001 |

| Satisfaction with Provider Communication (CAT) | 0.15 | 0.003 |

We performed adjusted analysis to examine which variables were independently associated with overall perceived kidney knowledge. We found that older age (β= −0.11, CI (−0.15, −0.07); p<0.001 per ten years), male sex (−0.13, (−0.24, −0.025); p=0.02), higher average eGFR (−0.02, (−0.03, −0.005); p=0.03 per 5 ml/min/1.73m2), not attending CKD education class (−0.42, (−0.58, −0.26); p<0.001), and less than ninth-grade health literacy (−0.21, (−0.36. −0.06); p=0.006) were independently associated with less overall perceived knowledge. A household income > $55,000 per year compared to ≤ $25,000 was associated with higher perceived knowledge (0.18, (0.004, 0.36); p=0.046), as well as knowing someone else with kidney disease (0.19, (0.07, 0.31); p=0.002). Years of education and number of doctor visits were not significantly associated with perceived kidney knowledge. Subgroup analysis of patients with an eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 revealed similar associations.

Associations with communication satisfaction

We examined associations between patient satisfaction with provider communication (CAT score as a continuous variable) and other patient characteristics including PiKS and KiKS. As shown in Table 1, the median (IQR) of the CAT was 5.0 (4.5, 5.0) and 56% of participants gave “excellent” ratings to all questions. In unadjusted analyses, CAT was only significantly associated with PiKS score (Table 4). In adjusted analysis, patients of older age (OR 1.21, 95% confidence interval (1.08, 1.35); p=0.001 per 10 years), higher eGFR (1.03 (1.01, 1.05); p<0.001 per 5 ml/min per 1.73 m2), and higher PiKS (2.13 (1.59, 2.86); p<0.0001 per 1.0-unit increase) were likely to have higher odds of being satisfied with communication with their provider. These associations were also adjusted for gender, race, health literacy, income, number of provider visits, and objective kidney knowledge. Patient satisfaction with provider communication was not associated with race, health literacy, income, or number of provider visits. Interestingly, in adjusted analysis, higher objective knowledge scores were associated with lower odds of satisfaction with provider communication (0.91 (0.84, 0.98); p=0.015, per 10% increase in KiKS).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted models of association of CAT with patient characteristics, using proportional odds logistic regression

| Patient characteristic | Unadjusted odds ratio (CI) |

P-value | Adjusted odds ratio (CI) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, per 10-year increase | 1.10 (0.96, 1.26) | 0.16 | 1.21 (1.08, 1.35) | 0.001 |

| Sex, female vs. male | 1.15 (0.72, 1.85) | 0.57 | 1.10 (0.64, 1.90) | 0.74 |

| Race, non-white vs. white | 0.69 (0.48, 1.01) | 0.06 | 0.78 (0.56, 1.08) | 0.14 |

| eGFR£, per 5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.61 | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | <0.001 |

| Yearly household annual income | ||||

| ≤$25,000 vs. > $55,000 | 0.74 (0.54, 1.02) | 0.06 | 0.95 (0.57, 1.60) | 0.85 |

| $25,000-$55,000 vs. > $55,000 | 0.94 (0.75, 1.17) | 0.57 | 0.98 (0.78, 1.22) | 0.85 |

| Health Literacy Level | ||||

| < 9th grade vs. ≥ 9th grade | 0.86 (0.50, 1.48) | 0.58 | 1.00 (0.44, 2.26) | 0.99 |

| Kidney doctor visits | ||||

| ≤ 2 in the past year vs. ≥ 3 | 1.06 (0.70, 1.61) | 0.78 | 1.09 (0.71, 1.68) | 0.70 |

| KiKS, per 0.1 (10%) increase | 0.97 (0.90, 1.05) | 0.50 | 0.91 (0.84, 0.98) | 0.015 |

| PiKS, per 1-unit increase | 1.75 (1.28, 2.38) | <0.001 | 2.13 (1.59, 2.86) | <0.0001 |

DISCUSSION

Similar to objective knowledge, perceived kidney disease knowledge is very limited in patients established within nephrology care, and shows similar associations with patient characteristics.14 Particularly striking is that nearly three-quarters of patients feel their knowledge about medications that can help the kidney is limited, and two thirds are not confident in their understanding about medications that harm the kidney, foods to avoid in case of low kidney function, or symptoms of CKD. Although 58% of participants had seen a kidney doctor at least three times in the past year, 25% reported they knew little or nothing about why they were sent to a kidney doctor. In addition, characteristics that put patients at risk for low perceived knowledge are nearly identical to objective knowledge. Interestingly, although the two types of knowledge share these similarities, their low-moderate association indicates they are not one and the same. In fact, the 0.32 correlation between the PiKS and the KiKS means that they only share ~10% common variance. Our observations of their unique and opposite associations with patient satisfaction further suggest that important distinctions exist between the two. Thus, in our study, perceived knowledge and objective knowledge appear largely to be two separate constructs.

Our study findings are consistent within the context of current literature where similarly designed research is found outside medicine. In one study exploring the associations between types of military knowledge in youths, perceived and objective knowledge scores showed a correlation of r = 0.29, p<0.01.15 While perceived knowledge influenced propensity (inclination for enlistment in the military) only factual knowledge was associated with actually joining. Similar to military knowledge, perceived and objective knowledge within the medical context are moderately associated,23,24 and appear to contribute differently not only to actions, but potentially to outcomes as well. Studies in adolescents exploring the relationship between knowledge and sexual behavior, show both perceived and objective knowledge serve as antecedents to predicting safer sex practices.16,25 Higher perceived knowledge is associated with safer sex practice and more confidence in ability to take actions to prevent sexually transmitted disease.25 Perhaps most interesting is research showing those with low objective knowledge about appropriate condom use along with high perceived knowledge are three times more likely not to use condoms during sex than those with other levels of objective and perceived knowledge.16 Recent work in patients with common medical conditions showed there was no relationship between medical knowledge and perceptions of being well informed.26 Collectively, these studies indicate perceived and objective knowledge are both important, and at best, moderately associated. However, they have an impact at different steps in the process of executing behaviors, and depending on their interactions, may have opposite effects on patient outcomes.

There have been several initiatives effective in improving kidney disease knowledge. The Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) is a screening program shown successful in identifying persons with poorly controlled CKD risk factors and reduced kidney function.27 This program enables people to gain insight about risk factors and, potentially, knowledge of a CKD diagnosis. In addition, the National Kidney Disease Education Program (NKDEP) has developed tools that clinicians can use in practice with patients to optimize communication about CKD.28 World-wide efforts are prominent as well, both for CKD screening and providing health education to patients, as exemplified by the International Society of Nephrology’s “Program for Detection and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease, Hypertension, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease in Developing Countries”.29 The potential benefits of these programs are many, including mitigating and preventing CKD by increasing patient awareness and objective knowledge. Our study revealed an interesting association of higher perceived knowledge with attendance in one kidney specific education session. Although this session targets increasing patient objective knowledge about disease and how to manage it, positive reinforcement and recognition techniques are incorporated into these visits. Such techniques reinforce patient confidence, which is both associated with25 and mediated by30 perceived knowledge, and which has been shown to have positive associations with optimal self-care behaviors in dialysis.31 Proactive endorsement by providers to patients using recognition, goal-setting, and positive reinforcement techniques are promoted to improve health care in chronic illness.32 Physician-patient communication incorporating these techniques could be used to increase knowledge, both objective and perceived, in patients with CKD.

Our study showed a positive relationship between perceived knowledge and satisfaction with provider communication, but a negative relationship was observed between satisfaction and objective knowledge. The reason for this is not entirely clear, but research in cancer indicates more factual knowledge has a distressful psychological impact on patients.33 Possibly similar feelings of stress and anxiety occur when patients gain insight and knowledge about CKD. In turn this may leave them less satisfied with communication on the topic. It is also conceivable that providers use the same educational approach to every patient and fail to recognize the heterogeneity in objective knowledge of their patient population. This in turn might lead to inadequate communication with patients who have higher objective knowledge but, perhaps, too sophisticated an approach with ones who have less objective knowledge. In any case, these findings highlight the importance of assessing disease knowledge level of patients prior to any intervention requiring provider communication. It also suggests that a person’s perception of their knowledge and what they actually know are not the same construct as revealed by very different associations with satisfaction.

Finally, our research has implications to existing and future studies examining the impact that educational interventions have on clinical outcomes. Although increased patient kidney disease knowledge is associated with improvements in dialysis patients, these associations are not large,6 and research in other chronic diseases show findings that are equivocal.34 Perhaps it is differences in the types of knowledge, or the fact that not all types are measured, that contribute to inconsistent findings of knowledge as a strong predictor of patient outcomes. Our study highlights the importance of accurately measuring and clearly defining all types of knowledge in this type of research.

There are limitations to this study. First, it is a cross sectional assessment whereby all survey questions were given to the participant to answer at one visit, thus causality cannot be inferred. Temporally, the objective knowledge questions were administered prior to the questions related to perceived knowledge and patient satisfaction; feasibly, difficulty answering objective knowledge questions could have influenced one or both of the other measures (PiKS and CAT). Although this design artifact was not intentional, we believe this strengthens our study findings. The observation of the two types of knowledge as largely different measures becomes even more valid when we acknowledge that the positive correlation between the two might be inflated due to a design artifact. If temporal sequence of questions influenced CAT scores, than the negative association observed could be diluted. Second, our study population is derived from several nephrology clinics within one tertiary referral center. Although race, sex, and age are very similar to patients with CKD in the U.S. population, 35 the results may not generalizable to patients seen in other practice settings, or in patient populations with end stage renal disease. This survey was not designed to capture knowledge in patients who may also face language barriers, where there may exist greater risk for lower disease knowledge. Third, there may be question as to whether the topics within our measures of perceived and actual knowledge were related, thus contributing to unexplained variance between them. We attempted to maximize overlap in their content by developing the questions in concert. We concurrently delivered the measures to eliminate the potential impact of temporal changes in either type of knowledge measured. Fourth, the CAT evaluates general satisfaction with overall communication during the visit, and it is feasible not all dialog was specific to CKD. Finally, there was limited variability in the CAT scores, with over half the participants showing a ceiling effect, thus also potentially attenuating the correlations with the two knowledge measures.

In conclusion, our study presents a valid measure of perceived kidney disease knowledge in patients with CKD, revealing much opportunity for improvement. Supporting our original hypothesis, we observed perceived knowledge is positively associated with objective knowledge and that the two types of knowledge are similar in many ways. However, of particular interest is the fact that the association between the two types of knowledge is not as high as originally anticipated. Additionally, perception of what one knows about disease is important but does not exhibit the same associations as objective knowledge, as evidenced by their very different relationships with the outcome, that is, patient satisfaction with communication. More research is needed in the area of patient disease-specific knowledge to inform and optimize our educational efforts along with examination of the impact these educational interventions have on outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design, Measures, and Procedures

This cross-sectional study was designed to capture concurrent measures of patients’ perceptions of their knowledge (perceived knowledge), patients’ objective disease knowledge and patient satisfaction with provider communication. Patients at one academic nephrology clinic were asked to complete a paper-and-pencil survey after their routine clinic appointments. The survey included nine questions on perceived knowledge (see Appendix online). To create the perceived knowledge questionnaire we first reviewed existing knowledge surveys used with patients with chronic diseases, including advanced CKD.5,8,11,13,36-38 We then developed an initial list of items relevant to areas important in CKD management. Those items were also designed to align with topic areas and questions in an existing objective survey of actual kidney disease knowledge. Initially there were 12 perceived knowledge questions. We convened experts from different disciplines involved with CKD care to evaluate questions for face and content validity. After an iterative process of feedback from our expert panel, a final perceived kidney knowledge survey of nine items was administered, where patients subjectively rated their perceived knowledge for each of the nine items on a scale from 1 (“I don’t know anything”) to 4 (“I know a lot”). Additional data were collected, including a previously validated measure of objective knowledge, KiKS,14 and a measure of patient satisfaction with provider communication, CAT.39 The CAT is a 15-item scale measuring patient satisfaction with physician interpersonal and communication skills, and uses a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 (“poor”) to 5 (“excellent”). The CAT assessed the nephrology doctor’s communication for the visit, including questions about whether the patient felt they received adequate information, whether the information was clearly understood, whether the patient felt involved in management decisions, and a rating of the interpersonal skills of the physician. Our patients may attend a specific kidney education class, where they learn information about CKD, nutrition, and have individualized discussion provided by an educator, and we asked patients if they had participated in this class. Literacy was assessed prior to administration of the survey using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), a measure of word recognition and pronunciation that exhibits high correlation with reading comprehension.40

Each attending physician in the nephrology clinic was assigned a unique code; however, additional provider characteristics were not collected. The majority of participants (89%) were seen by four attending physicians, coded 1-4. Code 5 (“other”) designated the five other attending doctors who saw the remaining participants.

Study Population

Patients at least 18 years of age, with established CKD stages 1-5, were enrolled from April through October 2009. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of CKD stages 1-5 as defined by National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF K/DOQI) guidelines and the ability to speak and read English.41 Patients completed at least one other visit with a nephrologist in the nephrology clinic prior to enrollment. Patients who were receiving dialysis or who had a working kidney transplant were excluded from the study. In addition, patients with a pre-existing cognitive or vision impairment were also excluded. The Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were offered $10.00 (USD) for completion of the study.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated as median and IQR for continuous variables, or frequency (%) for categorical variables. Stage of CKD was determined using laboratory serum creatinine and urinary protein measurements abstracted from the medical record. The 4-variable MDRD equation was applied to calculate estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).42,43 Where available, patient eGFR was an average taken from the two laboratory values most recent to the patient visit. When only one value was available, this value was used as the patient’s eGFR.

We evaluated the nine-item perceived knowledge survey in the following manner. An overall PiKS score was created by calculating an average of the patient’s ratings among items answered. Factor analysis allows us to examine whether more than one latent variable underlies a set of items (questions), and we used principal factor analysis to determine if there were separate sub-scales in our survey or if all nine items loaded on a single factor.22 Reliability for the final nine-item perceived kidney knowledge survey was calculated using Cronbach’s α, a measure of internal consistency for surveys with interval or ordinal responses.22 We established evidence of construct validity by defining a priori patient characteristics we hypothesized to be associated with kidney disease perceived knowledge (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The a priori associations between patient characteristics, perceived knowledge, and outcomes. CKD, chronic kidney disease.

The KiKS score (objective knowledge measure) was calculated as the percentage of correct responses on the 28-item objective kidney knowledge test.14 The CAT was analyzed as follows: first, a summary score was calculated by summing the patient responses and dividing by the total number of questions answered. The result is displayed as median (IQR). Second, a categorical variable was created by dividing participants into two groups: (1) those patients answering “excellent” to all 15 questions or (2) those who did not. We created this second, categorical variable, because the original investigators who developed the CAT suggested it was more useful, descriptively, to categorize the variable in this manner.39

To examine the association between PiKS and patient characteristics, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for categorical variables and Spearman’s rank-order correlations were calculated for continuous and ordinal variables. The independent effects of age, gender, race, education, average eGFR, doctor visits, income, knowing someone with CKD, taking a kidney education class, and health literacy were assessed in multivariable linear regression using the generalized estimating equation method with Huber-White robust sandwich estimator and exchangeable correlation structure,44 to account for clustering in outcome for patients by attending physician. Residuals of the generalized estimating equation regression were checked for normality, and all covariates were selected a priori and retained in the model regardless of statistical significance.

Additional exploratory analyses were performed examining adjusted effects on CAT of a priori-defined patient characteristics, including age, gender, race, average eGFR, number of doctor visits, income, health literacy, PiKS, and KiKS scores. Because the CAT was heavily skewed, the analysis was performed using proportional odds logistic regression with Huber-White robust sandwich estimator to account for a clustering by types of attending physician. Findings with a 2-sided p value ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Factor analysis and reliability calculations for the PiKS were assessed using STATA version 10.0 (College Station, TX). All other statistical calculations were performed using R software version 2.12.0.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by T32 DK007569, K23 DK080952 and K24 DK062849 from the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and The American Kidney Fund, Clinical Scientist in Nephrology Fellowship Grant (J.A.W.N.). The funding agencies did not have a role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study. This research has been presented, in part, at 2010 and 2011 NKF spring clinical meetings.

APPENDIX

Perceived Kidney Knowledge Survey (PiKS)

Please choose the response which most closely reflects HOW MUCH KNOWLEDGE YOU HAVE about each kidney topic:

| I don’t know anything (1) |

I know a little amount (2) |

I know a good amount (3) |

I know a lot (4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Medications that help the kidney | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. Medications that hurt the kidney | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. Foods that should be avoided if a person has low kidney function |

□ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. Your goal blood pressure | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. Understanding treatment options if kidney function gets worse |

□ | □ | □ | □ |

| 6. Symptoms of CHRONIC kidney disease |

□ | □ | □ | □ |

| 7. How kidney function is checked by a doctor |

□ | □ | □ | □ |

| 8. The functions of the kidney | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 9. Knowledge about why you have been sent to see a kidney doctor |

□ | □ | □ | □ |

The Kidney Disease Knowledge Survey (KiKS) is available at www.ajkd.org

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclosures

All the authors declared no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wingard R. Patient education and the nursing process: meeting the patient’s needs. Nephrol Nurs J. 2005 Mar-Apr;32(2):211–214. quiz 215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plantinga LC, Tuot DS, Powe NR. Awareness of chronic kidney disease among patients and providers. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010 May;17(3):225–236. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereira BJ. Optimization of pre-ESRD care: the key to improved dialysis outcomes. Kidney Int. 2000 Jan;57(1):351–365. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Burrows NR, et al. Comprehensive public health strategies for preventing the development, progression, and complications of CKD: report of an expert panel convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009 Mar;53(3):522–535. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devins GM, Binik YM, Mandin H, et al. The Kidney Disease Questionnaire: a test for measuring patient knowledge about end-stage renal disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(3):297–307. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90010-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devins GM, Mendelssohn DC, Barre PE, et al. Predialysis psychoeducational intervention and coping styles influence time to dialysis in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003 Oct;42(4):693–703. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00835-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devins GM, Mendelssohn DC, Barre PE, et al. Predialysis psychoeducational intervention extends survival in CKD: a 20-year follow-up. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005 Dec;46(6):1088–1098. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanaugh KL, Wingard RL, Hakim RM, et al. Patient dialysis knowledge is associated with permanent arteriovenous access use in chronic hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 May;4(5):950–956. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04580908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtin RB, Sitter DC, Schatell D, et al. Self-management, knowledge, and functioning and well-being of patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2004 Jul-Aug;31(4):378–386. 396. quiz 387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan AU, Hoffman B, Rosas SE. Patient perception of risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease morbidity and mortality. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(2):106–110. Spring. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelstein FO, Story K, Firanek C, et al. Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int. 2008 Nov;74(9):1178–1184. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon EJ, Wolf MS. Health literacy skills of kidney transplant recipients. Prog Transplant. 2009 Mar;19(1):25–34. doi: 10.1177/152692480901900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambers JK, Boggs DL. Development of an instrument to measure knowledge about kidney function, kidney failure, and treatment options. ANNA J. 1993 Dec;20(6):637–642. 650. discussion 643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright JA, Wallston K, Elasy TA, et al. Development and Results of a Kidney Disease Knowledge Survey Given to Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2011 Mar;57(3):387–395. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiggins B, March K, Luciano V, et al. Military Knowledge Study: Measuring Military Knowledge and Examining its Relationship with Youth Propensity. In: Joint Advertising MRaS, editor. Department of Defense. Defense Human Resources Activity. 2005. JAMRS Report No. 2005-2. ArlingtonSeptember. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rock EM, Ireland M, Resnick MD, et al. A rose by any other name? Objective knowledge, perceived knowledge, and adolescent male condom use. Pediatrics. 2005 Mar;115(3):667–672. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greer RC, Cooper LA, Crews DC, et al. Quality of Patient-Physician Discussions About CKD in Primary Care: A Cross-sectional Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010 Dec 3; doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitt MR, Miller MJ, Harrison DL, et al. Communicating non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug risks: Verbal counseling, written medicine information, and patients’ risk awareness. Patient Educ Couns. 2010 Dec 1; doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King K. Patients’ perspective of factors affecting modality selection: a National Kidney Foundation patient survey. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 2000 Jul;7(3):261–268. doi: 10.1053/jarr.2000.8123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004 Sep;27(3):237–251. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovac JA, Patel SS, Peterson RA, et al. Patient satisfaction with care and behavioral compliance in end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002 Jun;39(6):1236–1244. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeVellis R. Scale Development. Theory and Applications. 2nd Edition Vol. 26. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, California: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan MF, Zang YL. Nurses’ perceived and actual level of diabetes mellitus knowledge: results of a cluster analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2007 Jul;16(7B):234–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.el-Deirawi KM, Zuraikat N. Registered nurses’ actual and perceived knowledge of diabetes mellitus. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2001 Jan-Feb;17(1):5–11. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goh DS, Primavera C, Bartalini G. Risk behaviors, self-efficacy, and AIDS prevention among adolescents. J Psychol. 1996 Sep;130(5):537–546. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1996.9915020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sepucha KR, Fagerlin A, Couper MP, et al. How does feeling informed relate to being informed? The DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making. 2010 Sep-Oct;30(5 Suppl):77S–84S. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10379647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown WW, Peters RM, Ohmit SE, et al. Early detection of kidney disease in community settings: the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) Am J Kidney Dis. 2003 Jul;42(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narva AS, Briggs M. The National Kidney Disease Education Program: improving understanding, detection, and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009 Mar;53(3 Suppl 3):S115–120. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atkins R, Perico N, Codreanu I, et al. For ISN COMGAN Research Committee . Program for Detection and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease, Hypertension, Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease in Developing Countries. International Society of Nephrology; Feb 15, 2005. KHDC Program. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jerant A, Moore M, Lorig K, et al. Perceived control moderated the self-efficacy-enhancing effects of a chronic illness self-management intervention. Chronic Illn. 2008 Sep;4(3):173–182. doi: 10.1177/1742395308089057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curtin RB, Walters BA, Schatell D, et al. Self-efficacy and self-management behaviors in patients with chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008 Apr;15(2):191–205. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorig K. Partnerships between expert patients and physicians. Lancet. 2002 Mar 9;359(9309):814–815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07959-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tavoli A, Mohagheghi MA, Montazeri A, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with gastrointestinal cancer: does knowledge of cancer diagnosis matter? BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradley C. Health beliefs and knowledge of patients and doctors in clinical practice and research. Patient Educ Couns. 1995 Sep;26(1-3):99–106. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00725-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS . Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2010. 2010. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.White SL, Polkinghorne KR, Cass A, et al. Limited knowledge of kidney disease in a survey of AusDiab study participants. Med J Aust. 2008 Feb 18;188(4):204–208. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schatell D, Ellstrom-Calder A, Alt PS, et al. Survey of CKD patients reveals significant GAPS in knowledge about kidney disease. Part 1. Nephrol News Issues. 2003 Apr;17(5):23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schatell D, Ellstrom-Calder A, Alt PS, et al. Survey of CKD patients reveals significant gaps in knowledge about kidney disease. Part 2. Nephrol News Issues. 2003 May;17(6):17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Makoul G, Krupat E, Chang CH. Measuring patient views of physician communication skills: development and testing of the Communication Assessment Tool. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 Aug;67(3):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993 Jun;25(6):391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines and Clinical Practice Recommendations for Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007 Feb;49(2 Suppl 2):S12–154. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Jul 15;139(2):137–147. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Mar 16;130(6):461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1994. [Google Scholar]