Abstract

Introduction

‘Exception from informed consent for research’ (EFIC) is a rigorous procedure regulated by the FDA that requires community assent but allows enrollment without patient or family consent. Recently, several acute stroke trials have explored the use of EFIC to improve enrollment. We obtained ischemic stroke survivors’ opinions regarding hypothetical enrollment into a clinical trial at the time of their stroke without personal or proxy consent.

Methods

During 2005, 460 ischemic stroke patients (or their proxy) who met case criteria were prospectively interviewed and followed. After 2 years, patients were asked to think back to the time of their stroke and indicate whether they would have wished to be enrolled in an acute stroke research study before individual or proxy consent could be obtained, understanding that consent would be sought as soon as possible thereafter, and they rated how agreeable they would have been to acute stroke research with different levels of invasiveness. Predictors of a positive opinion regarding the hypothetical research were analyzed using logistic regression. Variables included in the model were age, race, sex, education, initial NIHSS, modified Rankin Scale prior to stroke and 30 days after stroke, and proxy versus patient responder.

Results

At 2 years after stroke, after excluding patient deaths, missing data or refusals, there were 194 patient/proxy responses included in this analysis. Overall, 72–79% of responses were favorable for chart review or blood draw without consent. The proportions answering agreeably to questions about medications or invasive strategies were smaller (62.9 and 59.8%). Older subjects were less likely to offer an agreeable response regarding use of medications [OR 0.97 per year (95% CI 0.94–0.99)] and invasive procedures [OR 0.97 per year (95% CI 0.94–0.99)]. Nonblacks tended to be more agreeable than blacks to invasive procedures. Men had twice the odds of being agreeable to blood draws than women.

Conclusions

We found that the majority of interviewed ischemic stroke patients were agreeable to being enrolled in acute stroke research with exception from informed consent, although the rates of agreement were lower than we expected among a cohort of patients who had already agreed to research. Older subjects, black race, and women were less likely to agree to blood draws or treatment strategies.

Key Words: Acute stroke, Angiography, Brain imaging, Stroke care, Transient ischemic attack

Introduction

When research in the acute setting is conducted under the regulations governing exception from informed consent (EFIC), subjects can be enrolled in a study without their prior consent only if stringent criteria are met [1]:

(1) The patient must be in an immediately life-threatening situation.

(2) It must not be feasible to obtain informed consent because of the patient's condition, because the intervention must be delivered prior to informed consent being possible, and because it is not practical to prospectively identify potential participants.

(3) The therapy under study must show the potential for direct benefit to the subject.

(4) It must not be practical to conduct the research without the waiver.

(5) The therapeutic window must be defined based on scientific evidence and the investigator must attempt to obtain consent from a legally authorized representative during that therapeutic window.

(6) If feasible, informed consent must be obtained, and any family members must be provided with the opportunity to object to the patient's participation.

(7) Additional protections must be in place to protect the rights and welfare of participants, including public disclosure and community consultation.

Much debate currently surrounds this last requirement [2,3,4,5,6]. The purpose of community consultation is to ensure that the research is respectful of the community in which it is conducted and as such, understanding community perceptions and opinions of the research is paramount [7,8]. While many studies have been conducted regarding patient opinions of EFIC research, including patients being evaluated in the emergency department [8,9,10,11,12], stroke patients have largely been excluded from these studies since most are cognitively impaired upon arrival in the emergency department. Also, few of these studies explored the impact of varying levels of invasiveness of the proposed research. Since several acute-stroke treatment trials have recently considered the use of EFIC, we sought to explore stroke survivors’ opinions regarding hypothetical enrollment into clinical trials of varying levels of invasiveness at the time of their stroke, without personal or proxy consent.

Methods

The Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study (GCNKSS) is a population-based epidemiological study of stroke in blacks and whites designed to measure temporal trends and racial differences in the incidence of stroke. The study period for the current analysis included patients whose strokes occurred from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2005.

As part of the GCNKSS, a prospective cohort was assembled using ‘hot pursuit’ methodology at all 17 local hospitals. Study nurses prospectively screened inpatient admission logs and emergency department logs to identify ischemic stroke patients. Once cases were identified and the treating physician had given permission to approach the patient, nurses asked the patient or their proxy to consent to participate in the cohort. An extensive interview was performed by a study nurse at baseline, and a blood draw was performed for genetic analysis. Follow-up interviews were performed at 3 and 12 months after the index stroke. At 12 months, subjects were asked to consent to additional follow-up at 2 years after stroke. Proxies were identified as the most closely related individual competent to consent for the patient, preferably a person living with the patient prior to the stroke.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to the study initiation. If the patient failed a standardized assessment of competency, proxy consent was obtained at initial enrollment and again at 12 months. Each patient's medical record was abstracted by a research nurse; data pertinent to patient characteristics, medical history, and stroke were collected. Data included stroke severity, baseline disability, past medical and surgical history, medications prior to stroke, social history/habits, diagnostic tests performed and results, treatments, and short-term outcomes. All abstracts were reviewed by a study physician to verify whether or not a stroke or transient ischemic attack occurred.

For patients who consented to the 2-year follow-up, an interview was conducted within 30 days of the 2-year anniversary of their index ischemic stroke. Patients (or their proxies) were asked to think back to the time of their stroke and indicate whether they would have accepted being enrolled in an acute stroke research study before individual or proxy consent could have been obtained. Five questions, reflecting different perceived levels of invasiveness, were asked. Interviewers were instructed to read the questions verbatim. Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with being enrolled in a study at the time of their stroke without their consent, or lack thereof, using a five-point Likert scale.

The script for the interviewing study nurse was the following:

The next question I have is about giving permission to be in a study. When patients come to the emergency room with a stroke, sometimes they can't consent for studies. This is because of confusion or trouble talking. Stroke patients are often not in studies because they can't give permission. Sometimes researchers might put someone into a study without their permission at that time. When family arrives or when the patient is able, they hear about the study and can agree or disagree then. We are not doing studies this way now in the Cincinnati area. However, since the idea is being talked about in other places, we would like your opinion as a stroke survivor. We would like you to think back to the time of your stroke and answer the following questions:

What would you have thought about being put into a study without your permission at the time (understanding that you or your family would have been told as soon as possible, with a choice to leave the study if you wanted)? Please answer each of the following questions with one of these choices:

(1) I think it's a good idea.

(2) I wouldn't mind.

(3) I'm not sure.

(4) It would bother me.

-

(5) Absolutely not.

(a) A study involving a nurse reviewing your medical records only?

(b) A study involving getting some of your blood only?

(c) A study involving getting some of your blood for genetics (looking at your DNA and genes) only?

(d) A study involving getting medications to treat my stroke?

(e) A study involving an invasive procedure, such as an angiogram, where doctors put catheters inside the blood vessels to try and treat your stroke?

For analysis, responses of ‘I think it's a good idea’ or ‘I wouldn't mind’ were considered agreeable responses. Predictors of an agreeable response were identified using multivariable logistic regression. We hypothesized that younger subjects, nonblack race, being female, being better educated, and having poorer functional status or more severe stroke would increase the odds of providing an agreeable response, based on prior research participation studies [13,14]. We also tested whether responses were given by the patient or a proxy was predictive of an agreeable response. Functional status was assessed using the modified Rankin Scale, and stroke severity was assessed using an estimated NIH Stroke Scale Score (NIHSSS) [15].

Data were managed with SAS version 8.02 (SAS Institute), and descriptive and comparative analyses were performed using SPSS v15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA).

Results

There were 502 ischemic stroke patients (or proxies) enrolled in the cohort from the larger epidemiology study. After physician review of the patients’ medical abstracts, it was determined that 460 cases met case criteria for ischemic stroke. At 12 months, 62 of the 460 subjects had died, 46 were lost to follow-up, and 23 refused to be interviewed. Thus, 329 subjects were interviewed at 12 months, of whom 259 verbally agreed to be interviewed at 2 years. At 2 years, 19 of the 259 had died, 31 were lost to follow-up, and 7 refused to be interviewed. An additional 8 subjects were interviewed but did not answer questions about inclusion in research without consent. Thus, 194 sets of responses were available for analysis. Included patients were significantly less likely to be black than excluded patients, and included patients tended to have lower prestroke modified Rankin scores (table 1). There were no other significant differences between included and excluded patients.

Table 1.

Study patient demographics: comparison of included versus excluded prospective cohort patients

| Excluded (n = 262) | Included (n = 194) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proxy response at 2 years | 47 (24.2) | ||

| Age at time of stroke, years | 69 (25–104) | 67 (28–93) | 0.219 |

| Race | |||

| Black | 76 (29.0) | 37 (19.1) | 0.015 |

| Nonblack | 186 (71.0) | 157 (80.9) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 130 (49.6) | 89 (45.9) | 0.429 |

| Male | 132 (50.4) | 105 (54.1) | |

| Education | |||

| Less than 12th grade | 78 (30.2) | 46 (23.8) | 0.317 |

| 12th grade or equivalent | 84 (32.6) | 70 (36.3) | |

| More than 12th grade | 96 (37.2) | 77 (39.9) | |

| Estimated NIHSSS | 4 (0–25) | 4 (0–22) | 0.209 |

| mRS prior to stroke onset | 1 (0–5) | 1 (0–4) | 0.054 |

| mRS after stroke | 3 (0–5) | 3 (0–5) | 0.024 |

Figures in parentheses represent range or percentage. mRS = Modified Rankin Scale.

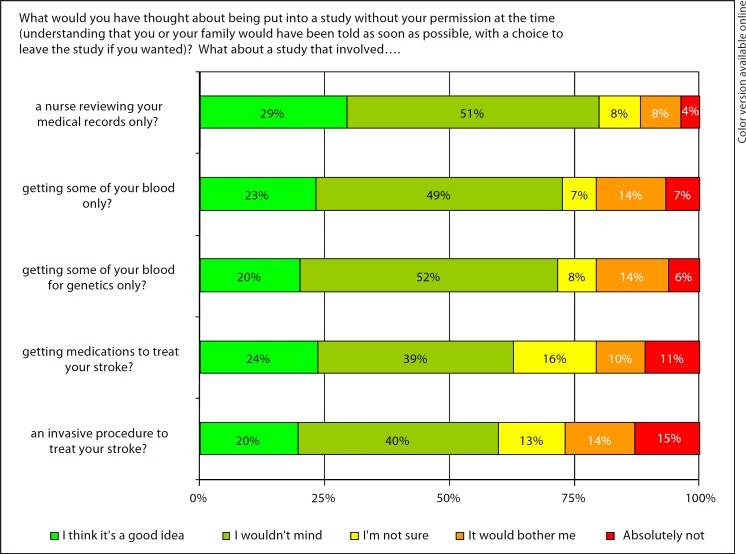

A large percentage (79.9%) of patients responded agreeably (‘I wouldn't mind’ or ‘I think it's a good idea’) to questions about chart review (question ‘a’) and obtaining blood with EFIC (question ‘b’ 72.7%; question ‘c’ 71.6%). The proportions answering agreeably to questions about treatment studies, including medications (question ‘d’) or invasive strategies (question ‘e’), were smaller (62.9 and 59.8%). Figure 1 describes the responses of the cohort to all questions.

Fig. 1.

Ischemic stroke survivors’ opinions regarding EFIC stroke research (n = 194).

Table 2 shows the effect of patient characteristics, functional status and stroke severity on the odds of providing an agreeable response. Older subjects were less likely to offer an agreeable response regarding use of medications and invasive procedures. Nonblacks tended to be more agreeable than blacks to invasive procedures, although the effect was only marginally significant. Men had twice the odds of being agreeable to blood draws for research purposes than women. Other factors were not predictive of whether or not a respondent would have been willing to participate in a research study with EFIC. The same pattern of findings was obtained when the outcome was modeled as a continuous variable (results not shown).

Table 2.

Logistic regression models testing the effect of age, race, sex, education, stroke severity and functional status on respondents’ willingness to have been enrolled in a research study with an EFIC, stratified by invasiveness of the proposed research (n = 194)

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A nurse reviewing your medical records only? | |||

| Age per year | 0.98 | 0.96−1.01 | 0.229 |

| Nonblack vs. black | 0.56 | 0.24−1.34 | 0.195 |

| Male vs. female | 1.54 | 0.71−3.33 | 0.277 |

| More than 12th grade vs. less than 12th grade education | 1.11 | 0.48−2.59 | 0.805 |

| Prestroke modified Rankin score | 1.29 | 0.89−1.86 | 0.174 |

| Estimated NIHSSS | 1.03 | 0.94−1.13 | 0.502 |

| Proxy vs. subject | 0.93 | 0.37−2.31 | 0.867 |

| Subsequent stroke | 0.95 | 0.34−2.66 | 0.914 |

| Getting some of your blood only? | |||

| Age per year | 0.98 | 0.95−1.00 | 0.088 |

| Nonblack vs. black | 0.84 | 0.36−1.96 | 0.680 |

| Male vs. female | 2.19 | 1.08−4.45 | 0.030 |

| More than 12th grade vs. less than 12th grade education | 0.93 | 0.43−2.01 | 0.844 |

| Prestroke modified Rankin score | 1.14 | 0.83−1.57 | 0.425 |

| Estimated NIHSSS | 1.00 | 0.93−1.08 | 0.962 |

| Proxy vs. subject | 0.64 | 0.29−1.44 | 0.283 |

| Subsequent stroke | 1.50 | 0.54−4.17 | 0.434 |

| Some of your blood for genetics only? | |||

| Age per year | 0.98 | 0.96−1.01 | 0.227 |

| Nonblack vs. black | 0.87 | 0.38−1.97 | 0.733 |

| Male vs. female | 1.59 | 0.80−3.15 | 0.183 |

| More than 12th grade vs. less than 12th grade education | 0.92 | 0.43−1.96 | 0.830 |

| Prestroke modified Rankin score | 1.00 | 0.73−1.36 | 0.989 |

| Estimated NIHSSS | 1.02 | 0.95−1.10 | 0.596 |

| Proxy vs. subject | 0.99 | 0.44−2.22 | 0.979 |

| Subsequent stroke | 1.02 | 0.40−2.58 | 0.965 |

| Getting medications to treat your stroke? | |||

| Age per year | 0.97 | 0.94−0.99 | 0.007 |

| Nonblack vs. black | 0.50 | 0.23−1.10 | 0.083 |

| Male vs. female | 1.44 | 0.75−2.75 | 0.274 |

| More than 12th grade vs. less than 12th grade education | 0.95 | 0.46−1.96 | 0.897 |

| Prestroke modified Rankin score | 0.92 | 0.68−1.24 | 0.577 |

| Estimated NIHSSS | 1.02 | 0.95−1.10 | 0.566 |

| Proxy vs. subject | 1.29 | 0.59−2.81 | 0.529 |

| Subsequent stroke | 1.51 | 0.60−3.77 | 0.378 |

| An invasive procedure to treat your stroke? | |||

| Age per year | 0.97 | 0.94−0.99 | 0.008 |

| Nonblack vs. black | 0.49 | 0.22−1.08 | 0.075 |

| Male vs. female | 1.66 | 0.87−3.17 | 0.125 |

| More than 12th grade vs. less than 12th grade education | 1.41 | 0.69−2.87 | 0.350 |

| Prestroke modified Rankin score | 0.95 | 0.71−1.28 | 0.741 |

| Estimated NIHSSS | 1.06 | 0.98−1.14 | 0.170 |

| Proxy vs. subject | 1.77 | 0.80−3.91 | 0.162 |

| Subsequent stroke | 0.94 | 0.39−2.26 | 0.885 |

Discussion

To our knowledge, stroke survivor opinion regarding EFIC stroke research has not been previously reported. We found that in every case, the majority of interviewed ischemic stroke patients were agreeable to being enrolled in acute stroke research with EFIC. However, opinions were more divided regarding studies involving medical treatments or invasive strategies. Agreement to participate in EFIC studies was not as high as we expected from this cohort of subjects who had already been enrolled in a longitudinal study of stroke outcomes that included blood draw, detailed interview and medical record review.

When exploring factors that might have affected a patient or proxy's opinions about being enrolled in studies conducted using EFIC, we found that increasing age was associated with less agreeable opinions regarding the use of medications and invasive treatments. Age was not a significant predictor for the less invasive strategies. We also found a gender difference: women were less likely to be agreeable to a blood draw with EFIC than men. However, this effect was not found for questions about invasive strategies. No other demographic and stroke severity variables were significantly associated with whether or not the subject (or proxy) would have been agreeable to participating in a study with EFIC. This is somewhat surprising, given that previous literature suggests gender and race often play an important role in willingness to participate in research [12], although this has not been entirely consistent [9,11]. Also, we had hypothesized that obtaining blood samples for genetics might be less agreeable to participants than a regular blood draw due to controversies surrounding genetics research. There did not appear to be a substantial difference between ‘getting a blood sample’ and ‘getting some of your blood for genetics (looking at your DNA and genes)’. Finally, educational level and stroke severity did not appear to impact the decision-making process at all, in contrast to our hypothesis that more educated subjects, as well as subjects who deal with serious deficits from their incident stroke, would be more willing to participate in research under the EFIC regulations.

There are several potential limitations to our analysis. Most importantly, we asked stroke survivors’ opinions about their experiences 2 years previously when they first had their strokes. In addition to removing the subject from the emotional and psychological stressors that exist proximal to the stroke event, there is likely a significant recall bias. However, our numbers are strikingly similar to other studies performed at the time of the acute event [9,11]. The cohort itself has a well-documented survival bias, which is exacerbated by asking these questions several years after the stroke. This survival bias might play into how agreeable potential participants are to EFIC research. Proxies were allowed to answer these questions, with the thought that the next of kin's opinion was valuable to evaluate. We found that it did not have a significant impact on the odds of agreeing to research with EFIC. A significant proportion of patients who agreed to the original interview declined to be followed for an additional 2 years. We hypothesize that patients who refused further follow-up may be even less likely to agree to these kinds of research questions, which might indicate that we have overestimated the proportion of stroke survivors agreeable to EFIC research. However, we are not able to test this hypothesis. A recent randomized trial evaluated the effect of a brief educational intervention on patients’ willingness to participate in EFIC research. Goldstein et al. [9] presented patients with either a standard questionnaire or a brief paragraph describing the EFIC research rationale and procedures. This intervention did have a positive effect, in that it improved willingness to participate by a modest amount. The format of our question asked in the current study essentially performed this kind of educational intervention, and so it is possible that we artificially improved our results. Finally, the FDA criterion that requires that there are no other possible treatments for the condition was omitted from the scripted questions, which may have altered the subjects’ agreement with the principles of EFIC.

Limitations notwithstanding, by asking those individuals who live with the sequelae of their stroke on a daily basis, we have queried those who would have been most impacted by research conducted with EFIC. As one might expect, enthusiasm for research conducted with EFIC declined as the level of invasiveness increased. Although research conducted with EFIC remains an important tool for researchers to test new, time-sensitive strategies, it should be applied judiciously and in full understanding that while a majority might be agreeable to such research, between 20 and 45% would not be agreeable to their inclusion. How this translates to societal acceptance of EFIC practices is as yet unknown and is a matter of ongoing debate.

References

- 1.Code of Federal Regulations 2008. 21CFR50.24.

- 2.Bateman BT, Meyers PM, Schumacher HC, Mangla S, Pile-Spellman J. Conducting stroke research with an exception from the requirement for informed consent. Stroke. 2003;34:1317–1323. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000065230.00053.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demarquay G, Derex L, Nighoghossian N, Adeleine P, Philippeau F, Honnorat J, et al. Ethical issues of informed consent in acute stroke. Analysis of the modalities of consent in 56 patients enrolled in urgent therapeutic trials. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:65–68. doi: 10.1159/000083250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosesso VN, Jr, Cone DC. Using the exception from informed consent regulations in research. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1031–1039. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichol G, Huszti E, Rokosh J, Dumbrell A, McGowan J, Becker L. Impact of informed consent requirements on cardiac arrest research in the United States: exception from consent or from research? Resuscitation. 2004;62:3–23. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitka M. Aiding emergency research aim of report on exceptions to informed consent. JAMA. 2007;298:2608–2609. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halperin H, Paradis N, Mosesso V, Jr, Nichol G, Sayre M, Ornato JP, et al. Recommendations for implementation of community consultation and public disclosure under the Food and Drug Administration's ‘Exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research’: a special report from the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative and Critical Care: endorsed by the American College of Emergency Physicians and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Circulation. 2007;116:1855–1863. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.186661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lecouturier J, Rodgers H, Ford GA, Rapley T, Stobbart L, Louw SJ, et al. Clinical research without consent in adults in the emergency setting: a review of patient and public views. BMC Med Ethics. 2008;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein JN, Delaney KE, Pelletier AJ, Fisher J, Blanc PG, Halsey M, et al. A brief educational intervention may increase public acceptance of emergency research without consent. J Emerg Med. 2008;39:419–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClure KB, DeIorio NM, Gunnels MD, Ochsner MJ, Biros MH, Schmidt TA. Attitudes of emergency department patients and visitors regarding emergency exception from informed consent in resuscitation research, community consultation, and public notification. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:352–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smithline HA, Gerstle ML. Waiver of informed consent: a survey of emergency medicine patients. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:90–91. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(98)90074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Triner W, Jacoby L, Shelton W, Burk M, Imarenakhue S, Watt J, et al. Exception from informed consent enrollment in emergency medical research: attitudes and awareness. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:187–191. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown M, Moyer A. Predictors of awareness of clinical trials and feelings about the use of medical information for research in a nationally representative US sample. Ethn Health. 2010;15:223–236. doi: 10.1080/13557851003624281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Giudice A, Plaum J, Maloney E, Kasner SE, Le Roux PD, Baren JM. Who will consent to emergency treatment trials for subarachnoid hemorrhage? Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:309–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams LS, Yilmaz EY, Lopez-Yunez AM. Retrospective assessment of initial stroke severity with the NIH Stroke Scale. Stroke. 2000;31:858–862. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]