Abstract

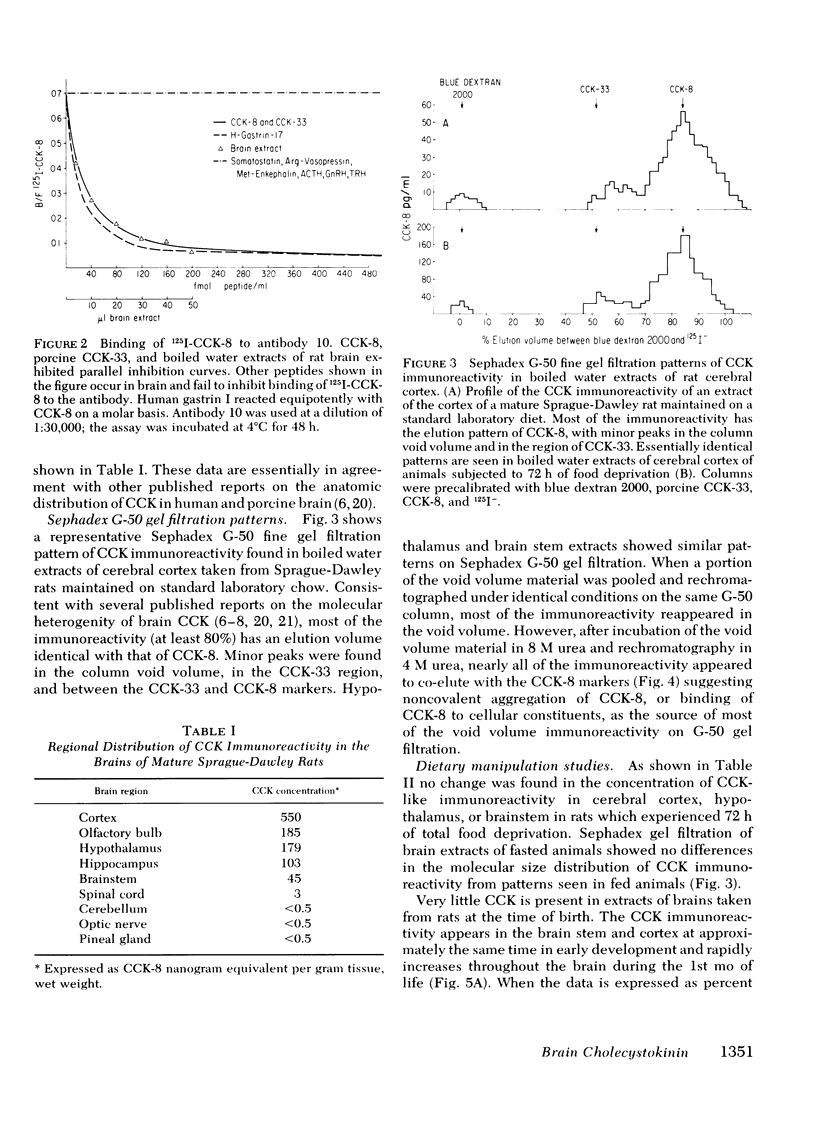

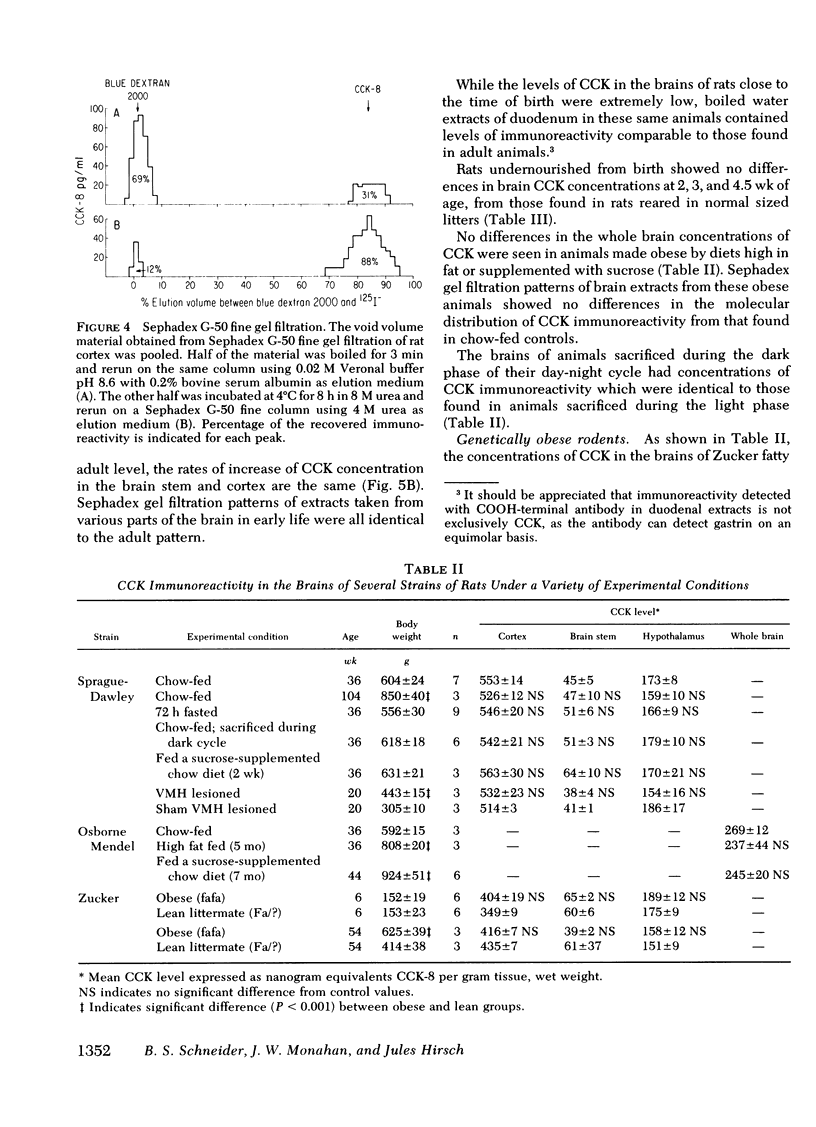

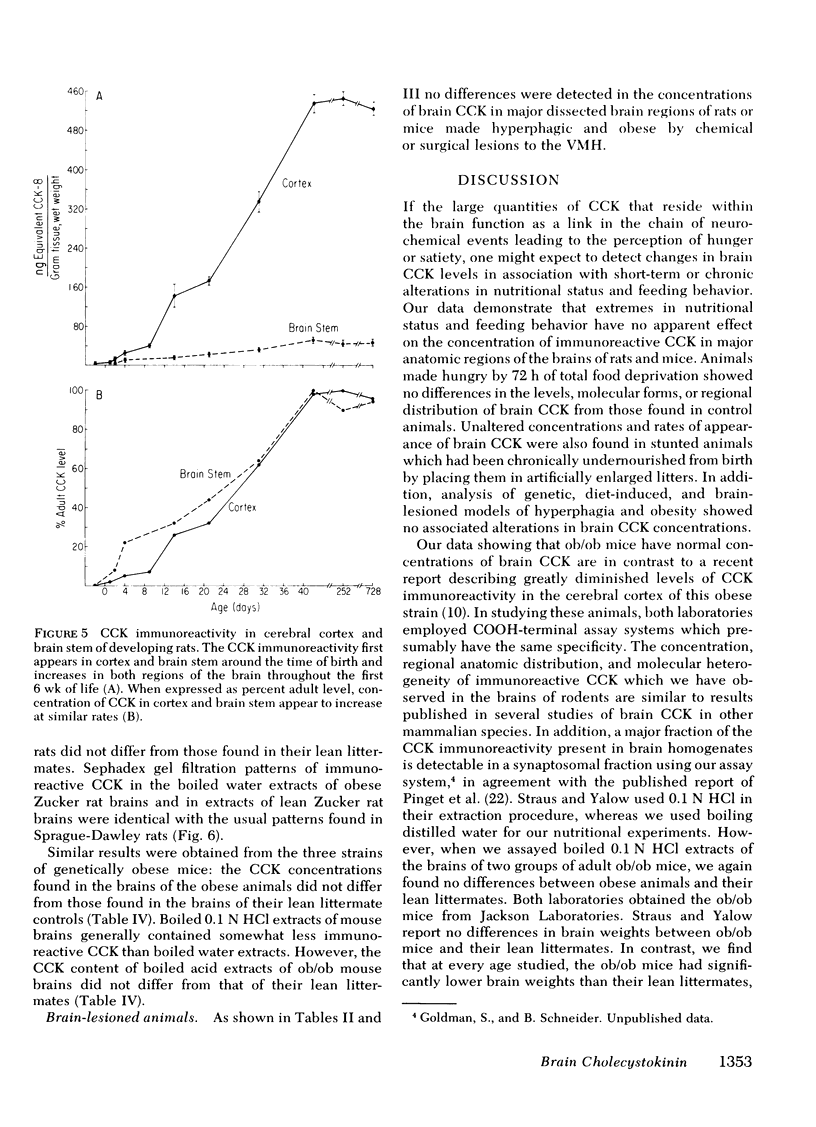

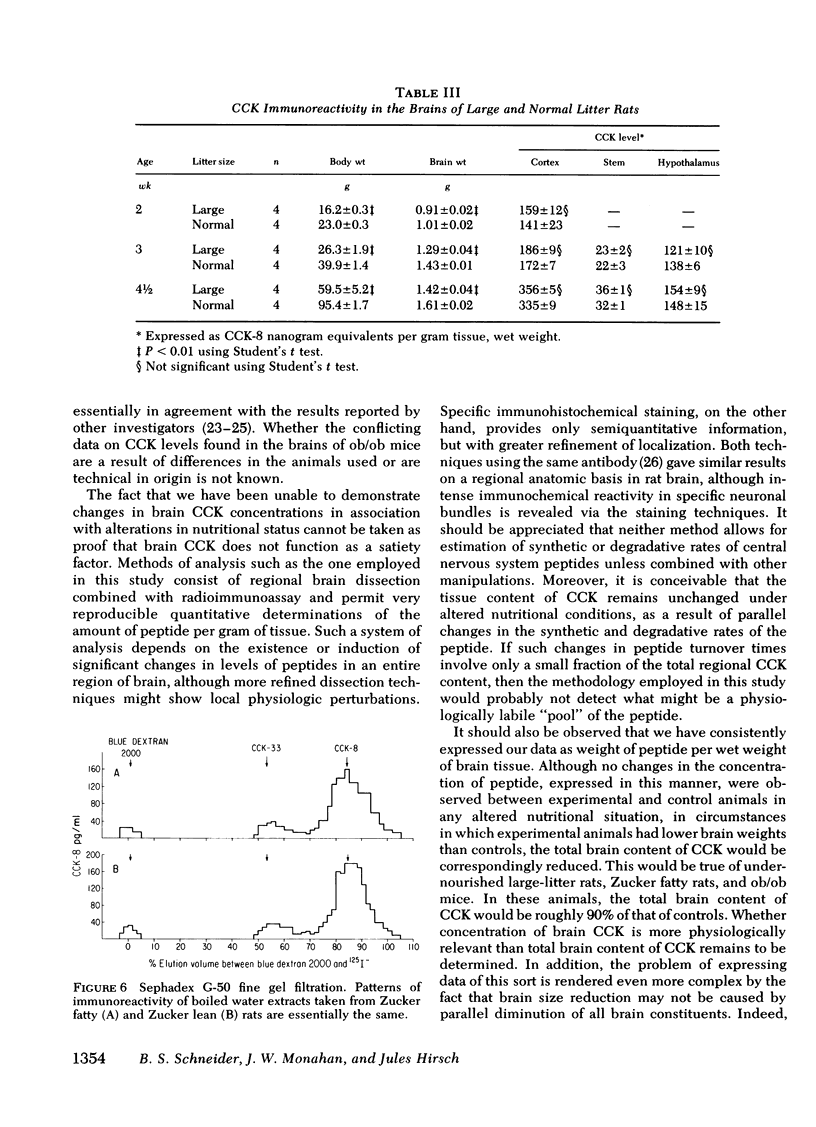

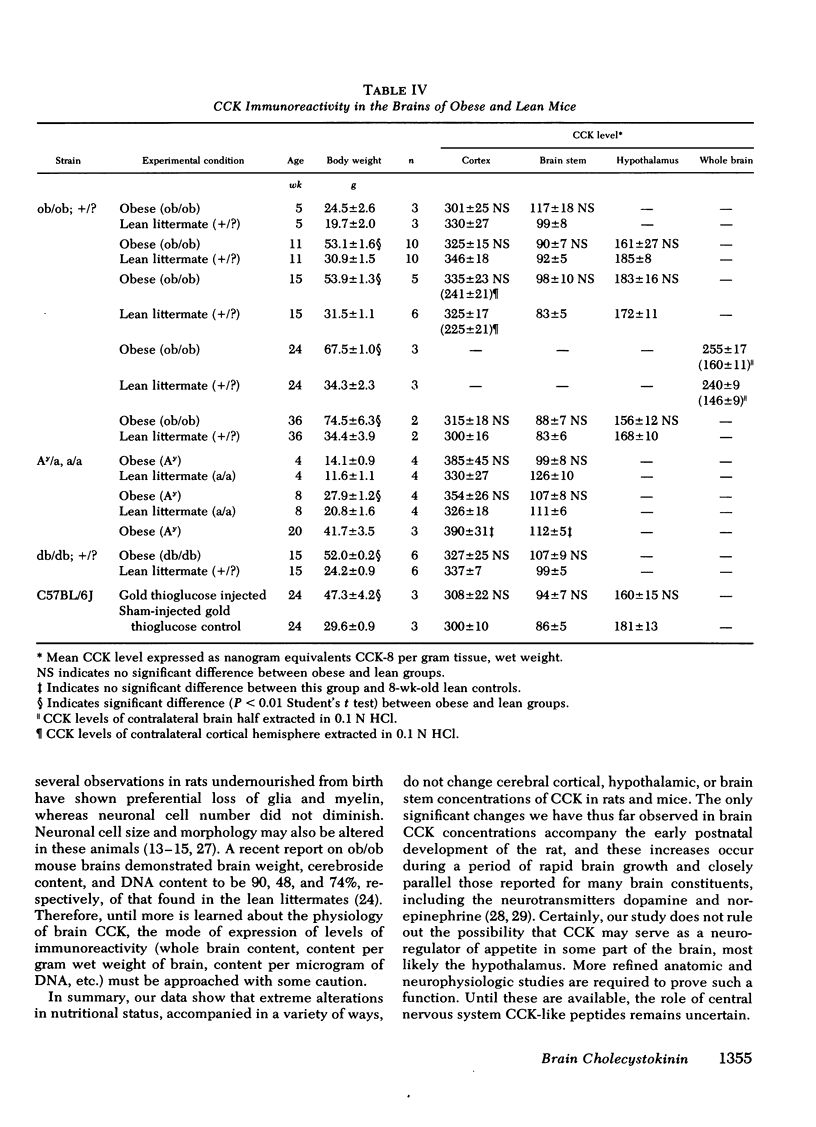

Under certain conditions, exogenously administered cholecystokinin (CCK) or its COOH-terminal octapeptide can terminate feeding and cause behavioral satiety in animals. Furthermore, high concentrations of CCK are normally found in the brains of vertebrate species. It has thus been hypothesized that brain CCK plays a role in the control of appetite. To explore this possibility, a COOH-terminal radioimmunoassay was used to measure concentrations of CCK in the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and brain stem of rats and mice after a variety of nutritional manipulations. CCK, mainly in the form of its COOH-terminal octapeptide, was found to appear in rat brain shortly before birth and to increase rapidly in cortex and brain stem throughout the first 5 wk of life. Severe early undernutrition had no effect on the normal pattern of CCK development in rat brain. Adult rats deprived of food for up to 72 h and rats made hyperphagic with highly palatable diets showed no alterations in brain CCK concentrations or distribution of molecular forms of CCK as determined by Sephadex gel filtration of brain extracts. Normal CCK concentrations were also found in the brains of four strains of genetically obese rodents and in the brains of six animals made hyperphagic and obese by surgical or chemical lesioning of the ventromedial hypothalamus. It is concluded that despite extreme variations in the nutritional status of rats and mice, CCK concentrations in major structures of the brain are maintained with remarkable constancy.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Antin J., Gibbs J., Holt J., Young R. C., Smith G. P. Cholecystokinin elicits the complete behavioral sequence of satiety in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975 Sep;89(7):784–790. doi: 10.1037/h0077040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese G. R., Traylor T. D. Developmental characteristics of brain catecholamines and tyrosine hydroxylase in the rat: effects of 6-hydroxydopamine. Br J Pharmacol. 1972 Feb;44(2):210–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1972.tb07257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbing J., Sands J. Vulnerability of developing brain. IX. The effect of nutritional growth retardation on the timing of the brain growth-spurt. Biol Neonate. 1971;19(4):363–378. doi: 10.1159/000240430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockray G. J. Immunochemical evidence of cholecystokinin-like peptides in brain. Nature. 1976 Dec 9;264(5586):568–570. doi: 10.1038/264568a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish I., Winick M. Effect of malnutrition on regional growth of the developing rat brain. Exp Neurol. 1969 Dec;25(4):534–540. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(69)90096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J., Smith G. P. Cholecystokinin and satiety in rats and rhesus monkeys. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977 May;30(5):758–761. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.5.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J., Young R. C., Smith G. P. Cholecystokinin decreases food intake in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1973 Sep;84(3):488–495. doi: 10.1037/h0034870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J., Young R. C., Smith G. P. Cholecystokinin elicits satiety in rats with open gastric fistulas. Nature. 1973 Oct 12;245(5424):323–325. doi: 10.1038/245323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER W. M., GREENWOOD F. C. Preparation of iodine-131 labelled human growth hormone of high specific activity. Nature. 1962 May 5;194:495–496. doi: 10.1038/194495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis R. B., Corrêa F. M., Uhl G. R., Schneider B., Snyder S. H. Cholecystokinin octapeptide-like immunoreactivity: histochemical localization in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Jan;76(1):521–525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. R., Hirsch J. Cellularity of adipose depots in six strains of genetically obese mice. J Lipid Res. 1972 Jan;13(1):2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. R., Zucker L. M., Cruce J. A., Hirsch J. Cellularity of adipose depots in the genetically obese Zucker rat. J Lipid Res. 1971 Nov;12(6):706–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison S. Intraperitoneal and intracranial cholecystokinin depress operant responding for food. Physiol Behav. 1977 Dec;19(6):819–824. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margules D. L., Moisset B., Lewis M. J., Shibuya H., Pert C. B. beta-Endorphin is associated with overeating in genetically obese mice (ob/ob) and rats (fa/fa). Science. 1978 Dec 1;202(4371):988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.715455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J. E., Straus E., Yalow R. S. Cholecystokinin and its COOH-terminal octapeptide in the pig brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Jul;74(7):3035–3037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinget M., Straus E., Yalow R. S. Localization of cholecystokinin-like immunoreactivity in isolated nerve terminals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Dec;75(12):6324–6326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.12.6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeld J. F. Immunochemical studies on cholecystokinin. II. Distribution and molecular heterogeneity in the central nervous system and small intestine of man and hog. J Biol Chem. 1978 Jun 10;253(11):4022–4030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier J., Rogers J., Shibasaki T., Guillemin R., Bloom F. E. Opioid peptides and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone in genetically obese (ob/ob) mice during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Apr;76(4):2077–2080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus E., Muller J. E., Choi H. S., Paronetto F., Yalow R. S. Immunohistochemical localization in rabbit brain of a peptide resembling the COOH-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Jul;74(7):3033–3034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus E., Yalow R. S. Cholecystokinin in the brains of obese and nonobese mice. Science. 1979 Jan 5;203(4375):68–69. doi: 10.1126/science.758680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus E., Yalow R. S. Species specificity of cholecystokinin in gut and brain of several mammalian species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Jan;75(1):486–489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhaeghen J. J., Signeau J. C., Gepts W. New peptide in the vertebrate CNS reacting with antigastrin antibodies. Nature. 1975 Oct 16;257(5527):604–605. doi: 10.1038/257604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winick M., Noble A. Cellular response in rats during malnutrition at various ages. J Nutr. 1966 Jul;89(3):300–306. doi: 10.1093/jn/89.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kroon P. H., Speijers G. J. Brain deviations in adult obese-hyperglycemic mice (ob/ob). Metabolism. 1979 Jan;28(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(79)90160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]