Abstract

Sheep are seasonal breeders, experiencing a period of reproductive quiescence during spring and early summer. During the non-breeding period, kisspeptin expression in the arcuate nucleus is markedly reduced. This strongly suggests that the mechanisms that control seasonal changes in reproductive function involve kisspeptin neurons. Kisspeptin cells appear to regulate GnRH neurons and transmit sex-steroid feedback to the reproductive axis. Since the non-breeding season is characterized by increased negative feedback of estrogen on GnRH secretion, the kisspeptin neurons seem to be fundamentally involved in the determination of breeding state. The reduction in kisspeptin neuronal function during the non-breeding season can be corrected by infusion of kisspeptin, which causes ovulation in seasonally acyclic females.

Introduction

Most species exhibit seasonality of reproductive function and the means by which this is controlled remains a subject of scientific intrigue. Certainly it is well known that changes in day length (photoperiod) provide a means of measuring circannual time and this is perceived and translated into a physiological signal by the pineal gland, through the nighttime secretion of melatonin. Melatonin is produced at night in direct proportion to the period of darkness. The pattern of secretion of melatonin provides information that is apparently ‘read’ by cells within the brain that possess the relevant receptors and control reproductive function. To date, only limited information exists regarding the distal arm of this pathway, since it has been difficult to determine which cells possess melatonin receptors and how these cells change function with season.

Reproductive function is driven by the gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) cells of the brain, which provide stimulus to pituitary gonadotropes. The pulsatile secretion of GnRH into the hypophysial portal system determines the pattern of secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary and also stimulates the production of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) [5, 9] secretion is modulated by a wide range of brain systems, including those influenced by sex-steroid feedback, nutrition and stress as well as season. GnRH cells do not express the subtype of the estrogen receptor (ER) that transduces the feedback effects of estrogen, namely ERα, so considerable effort has focused on the means by which the feedback loop from the gonads to the GnRH cells is constructed [5]. The recent identification of the kisspeptin system and recognition that the kisspeptin cells express ERα [13] has led to a significant advance in our understanding of estrogen feedback. Since kisspeptin cells provide direct synaptic input to GnRH cells [20] and kisspeptin is a potent stimulator of GnRH secretion [26], these cells are ideally placed to transmit estrogen feedback information to the brain cells that drive the reproductive process.

A full dissertation on the role of kisspeptin cells in steroid feedback is provided in another chapter [35] of this volume, but the issue is relevant to seasonality of reproduction, because there is a marked seasonal change in the negative feedback effect of estrogen with season, that is fundamental to transition from breeding to non-breeding season and vice versa [22]. For the purpose of this chapter, it is sufficient to recognize that kisspeptin cells express ERα, that negative feedback effects of estrogen are important in determination of the pattern of GnRH secretion that dictates the seasonal breeding cycle and that the two are linked. This review focuses on data from the female sheep, which has been used extensively to examine neuroendocrine mechanism of seasonal breeding. Sheep are short-day breeders, so reproductive activity is stimulated by reducing photoperiod. Accordingly, ovarian cycles occur in the late summer-autumn period. Periods of reproductive activity or inactivity can be artificially imposed by short-day or long-day photoperiod respectively.

Patterns of GnRH and gonadotropin secretion during the breeding season and the non-breeding season

The pulsatile pattern of GnRH secretion from the brain determines the pattern of pulsatile LH secretion from the pituitary, although there are some modulatory effects of sex steroids that provide further control at the level of the gonadotrope [8]. It is the frequency of GnRH/LH pulses that appears to be the over-riding determinant of reproductive function, with upregulation during the follicular phase of the ovarian cycle, reaching a maximum at the time of the estrogen-induced preovulatory surge [7]. This cyclic pattern of GnRH/LH secretion ceases during the non-breeding season, when the ovaries become quiescent. There are two mechanisms that relate to this seasonal shift; steroid-independent and steroid-dependent effects [30]. Regarding the former, there is a reduction in the frequency of LH pulses in ovariectomised ewes during the time of year that normal (gonad-intact) ewes are acyclic [30]. In addition, in ovariectomised ewes bearing implants that release a constant amount of estrogen, the pulsatile release of GnRH and LH is markedly reduced during the non-breeding period [22]. This exemplifies the steroid-dependent effect of photoperiod to suppress the gonadotropic axis by increasing the negative feedback actions of estrogen in the non-breeding season. This is considered to be fundamental to the process that causes suppression of reproductive behaviour and cyclic gonadotropin secretion in the female [19]. Since kisspeptin cells possess ERα, they provide excellent candidates for the steroid-dependent effect and transmission of the negative feedback effect of estrogen to GnRH cells.

Changes in expression of kisspeptin cells with season

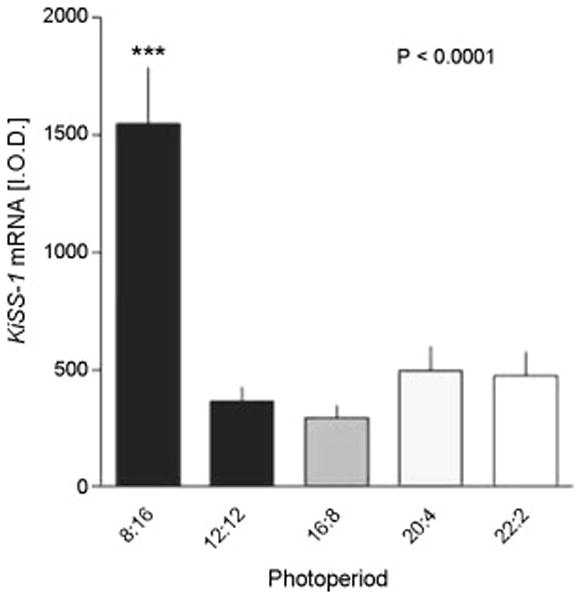

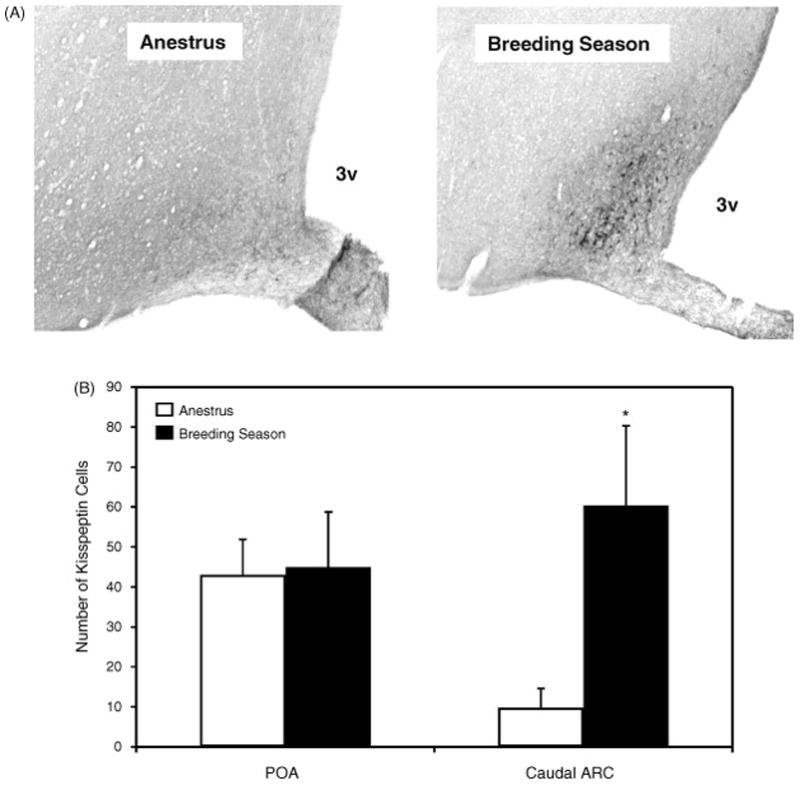

If kisspeptin cells are integral determinants of GnRH/LH secretion in the different seasons, one might expect changes in the expression of the kisspeptin gene (Kiss1) with season. Soay sheep are highly seasonal [18], so we conducted a study in this breed to determine gene expression on different photoperiods. The level of expression of Kiss1 in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus of ovary-intact ewes on a photoperiod of 8 light: 16 dark was at least 3-fold higher than that seen in animals on longer photoperiods (Figure 1) [39]. This could represent the effects of seasonal differences in endogenous ovarian steroid production. However, using ovariectomised Blackface ewes bearing estrogen implants in anestrus, we observed a similar marked reduction in the number of immunoreactive kisspeptin cells in the arcuate nucleus of (Figure 2) [36]. Importantly, the seasonal effect on the number of kisspeptin-positive cells was seen in the arcuate nucleus, but not in the preoptic area. These two populations of kisspeptin neurons may have different roles in relation to GnRH secretion. The arcuate nucleus population is larger than that of the preoptic area [35] and the former also varies with the stage of the ovine estrous cycle, with upregulation in the preovulatory period [12]. Furthermore, it is well accepted that negative and positive feedback effects of estrogen are transmitted to GnRH cells via the mediobasal hypothalamus in the ewe [1, 3]. Thus, it is considered that the arcuate nucleus kisspeptin neurons are highly relevant to the control of GnRH neurons, whereas the function of the preoptic kisspeptin neurons is less clear [35]. The higher Kiss1 expression in the arcuate nucleus of ewes exposed to short photoperiod and in the follicular phase of the cycle in the breeding season is consistent with this proposal and raised the possibility that annual changes in kisspeptin contribute to seasonal reproduction.

Figure 1.

Kiss1 expression in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the Soay ewe brain in different photoperiods. The animals were held in artificial photoperiods of 8h light (L), 16h dark (D), 12L:12D, 16L:8D, 20L:24D or 22L:2D. Integrated optical density measurements of Kiss1 expression at the level of the ARC are shown and data are mean ± SEM (n ≤ 8). ***P<0.0001 compared to other groups. Adapted from Reference [39] with permission.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of immunohistochemistry showing kisspeptin-ir cells in the ARC (A) of the ewe brain. 3V, third ventricle. The number of kisspeptin-ir cells in the POA and the caudal ARC.of the ovariectomised ewes bearing estrogen implants during the non-breeding and breeding seasons ewes are shown in panel B. Values are means (± SEM). *, P < 0.05 non-breeding v breeding season. Adapted from Reference [36], with permission.

There are 3 components of estrogen feedback that are relevant to the control of GnRH and gonadotropin secretion. These are short-term negative feedback, long-term negative feedback and a transient positive feedback [6]. The positive feedback effect occurs in response to rising estrogen levels during the follicular phase of the estrous cycle and does not occur in ewes during the non-breeding season because a normal follicular phase rise in estrogen does not occur [15]. It is important to distinguish the transient positive feedback effect of estrogen to stimulate preovulatory events from the chronic effect of estrogen to suppress GnRH function.

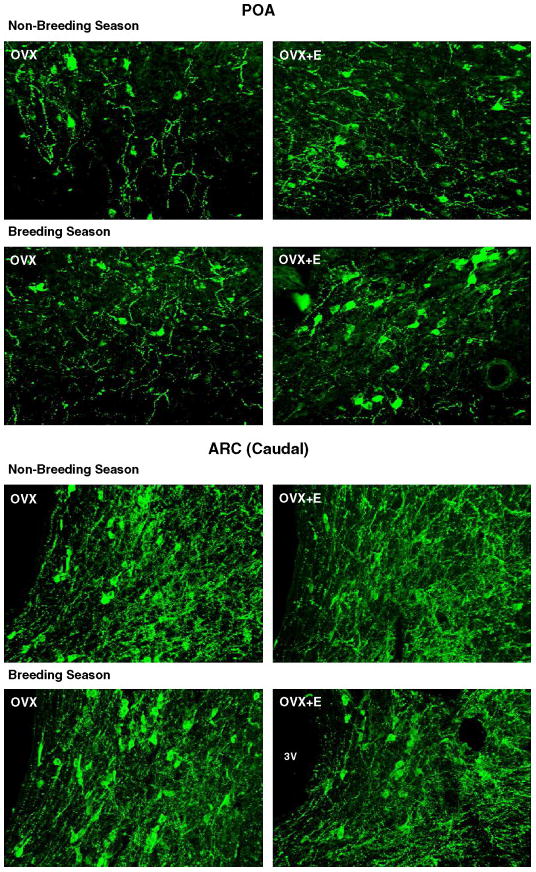

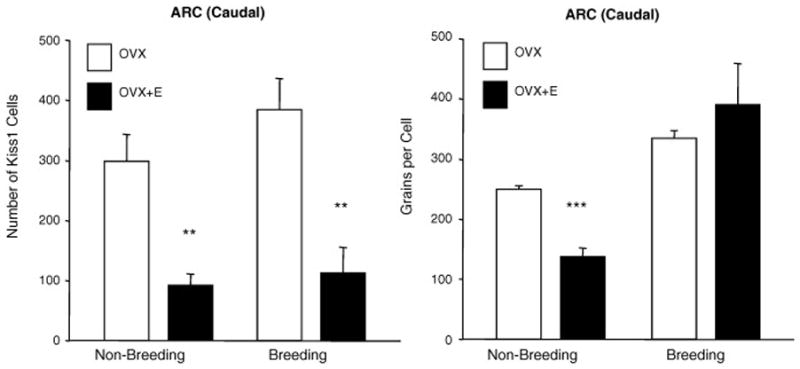

Working with ewes, it has been convincingly demonstrated that the over-riding determinant of seasonal cyclicity/acyclicity is the extent to which negative feedback suppresses GnRH activity [15] and the studies described below relate to the chronic effect of estrogen. Whereas the transient positive feedback effect that occurs in the preovulatory phase of the estrous cycle is associated with increased Kiss1 expression in the arcuate nucleus [12] the overriding effect of increased negative feedback during the non-breeding season is associated with an effect of estrogen to reduce Kiss1 expression and kisspeptin levels [36]. Marked reduction in Kiss1 (Fig 1) and kisspeptin cell number (Fig 2) is thought to be associated with reduced reproductive activity in the non-breeding season. Data from ovariectomised ewes suggest that the effect of season, which may integrally involve kisspeptin neurons, is estrogen-dependent. Thus, using immunohistochemistry, we found that the number of kisspeptin-positive cells in the arcuate nucleus and the preoptic area was similar in ovariectomised ewes at the times of the year when normal animals would be in the breeding and non-breeding seasons [15, 36]. On the other hand, chronic estrogen treatment reduced cell number in the arcuate nucleus [36] (Figure 3). The effect was seen in both seasons in the rostral and mid-arcuate region, but there was a seasonal effect in the caudal arcuate nucleus (Figure 3), such that chronic estrogen treatment reduced kisspeptin levels in the non-breeding season but not the breeding season. It is the caudal region in which a cyclic change in expression of Kiss1 is seen, with up-regulation occurring in the preovulatory period [12]. This suggests that the caudal region is most relevant to the positive feedback effect of estrogen to generate the preovulatory surge and it seems salient that this is the region in which a seasonal effect to reduce kisspeptin cell activity is clearly apparent when estrogen treatment is applied. In situ analysis of Kiss1 expression presented a more complex picture, since the number of cells expressing the gene in the caudal arcuate nucleus was seen to be lower with estrogen treatment in both seasons, whereas the level of expression/cell was lowered only in the non-breeding season [36] (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs showing kisspeptin-ir cells in sections of the POA and caudal ARC of ovariectomised (OVX) with or without estrogen (E) treatment during the non-breeding and breeding seasons. 3V, third ventricle. Adapted from Reference [36], with permission.

Figure 4.

Expression of KiSS1 expression in the caudal ARC of ovariectomised (OVX) with or without estrogen (E) treatment during the non-breeding and breeding seasons. Left panels show the number of Kiss1 mRNA-expressing cells and right panels show the number of silver grains/Kiss1 cell (expression per cell). Values are means (± SEM). **, P < 0.01 ***, P < 0.001 non-breeding v breeding season. Adapted from Reference [36], with permission.

It may be an apparent paradox to propose that kisspeptin neurons in the caudal arcuate nucleus are implicated in the positive feedback effect of estrogen and also the negative effect of estrogen that determines seasonal breeding status. Are the same cells or different cells involved in the two types of feedback? This is conceivable, based on the following reasoning. Firstly, positive feedback does not occur in the anestrous season because any rise in estrogen levels drives down LH pulsatility and a normal follicular phase cannot ensue [15]. On the other hand, if adequate estrogen is either administered or provided by some artificial stimulus of the ovaries (see below), then a positive feedback response occurs. Indeed, there is no difference in the ability of estrogen to elicit this transient positive response in either season [27]. An important feature of this system is that, in the normal animal, the overriding influence in the non-breeding season is the negative feedback effect of even very low levels of estrogen, such that a transient rise in estrogen to levels that stimulate positive feedback never occurs. Thus, available data suggests that in the non-breeding season the ability of chronic, low levels of estrogen to suppress kisspeptin is enhanced, while the ability of higher, follicular phase levels of estrogen to increase kisspeptin in the same cells remains unchanged. Understanding the cellular mechanisms responsible for these two feedback effects of estrogen on kisspeptin, and why one may be affected by season and not the other, would be a useful advance in our knowledge.

Estrogen treatment increases the number of kisspeptin cells seen with immunohistochemistry in the preoptic area and consistent changes are seen with expression of Kiss1 [36] (Figures 3 and 4). These changes are independent of season, further reinforcing the notion that the cells of the arcuate nucleus are most relevant to seasonal changes in regulation of GnRH cells. Whereas this work strongly suggests that kisspeptin cells are fundamentally involved in the seasonal regulation of reproduction, further work is required to resolve the discrepancies that exist between immunocytochemical and in situ hybridization data. Furthermore, some deeper investigation of the importance of the different subsets of kisspeptin neurons (arcuate nucleus subsets and preoptic subset) in the control of GnRH neurons is required.

Our recent immunohistochemical study of kisspeptin cells across the breeding and non-breeding seasons of female sheep also showed changes in RFRP/gonadotropin inhibitory hormone (GnIH) neurons that were opposite to those of kisspeptin neurons [36]. GnIH is an RF-amide peptide that exerts inhibitory control over the reproductive system and appears to be involved in changes that occur with season in birds and mammals [2, 21], but further work is required to consolidate the findings to date. In mammals, the relevant gene appears to encode RFRP-1 and RFRP-3 [10, 21, 29]. Work in the hamster [21, 29] and the sheep [10] indicate that this peptide is involved in the control of reproduction in mammals, with evidence that it may be a factor that determines seasonality of breeding. The data appear strong in the sheep and the fact that it is regulated by melatonin in hamsters [29] also provides a good reason for further investigation. The work in the hamster is reviewed in another chapter in this volume [33].

Evidence that Melatonin may drive the Seasonal Changes in Kisspeptin and Seasonal Change in input to GnRH cells

As mentioned in the Introduction, melatonin is an endocrine ‘readout’ of darkness, which measures photoperiod and signals to neuroendocrine systems controlling reproduction. In the sheep, various lines of evidence indicate that the site at which melatonin acts to regulate GnRH/gonadotropin secretion is the pre-mammillary nucleus of the basal hypothalamus [24]. It is not yet established how this is translated into a change in GnRH/gonadotropin secretion, but it seems particularly salient that the premammillary hypothalamic area of the ovine brain includes the caudal arcuate nucleus [34]

Work in both the Siberian and the Syrian hamster has investigated the role of melatonin in seasonal changes in kisspeptin activity and provides strong indications that these are dependent upon melatonin ( [29], and reviewed in [33] ). Even though Syrian hamsters are long-day breeders, whereas sheep are short-day breeders, Kiss1 expression is downregulated in both the AVPV and the arcuate nucleus under short-day (inhibitory) photoperiods in the Syrian hamster. Interestingly, the same is not true for the Siberian hamster and the reason for this is not clear at present [33]. The data from the Siberian hamster and the sheep concur, in that activity of kisspeptin neurons is reduced under inhibitory photoperiod.

In the sheep, the A15 nucleus of the hypothalamus, in which dopaminergic neurons are found, is thought to play a pivotal role in seasonal reproduction [1, 23]. ERα-expressing neurons in the arcuate nucleus, amongst others, project to the A15 nucleus, allowing for the possibility that kisspeptin cells transmit estrogen feedback information to the dopaminergic neurons that are thought to be involved in seasonality of reproduction. On the other hand, input to kisspeptin cells could arise from the A15 cells, with relay of information to GnRH cells. Such intra-hypothalamic circuitry remains to be deciphered.

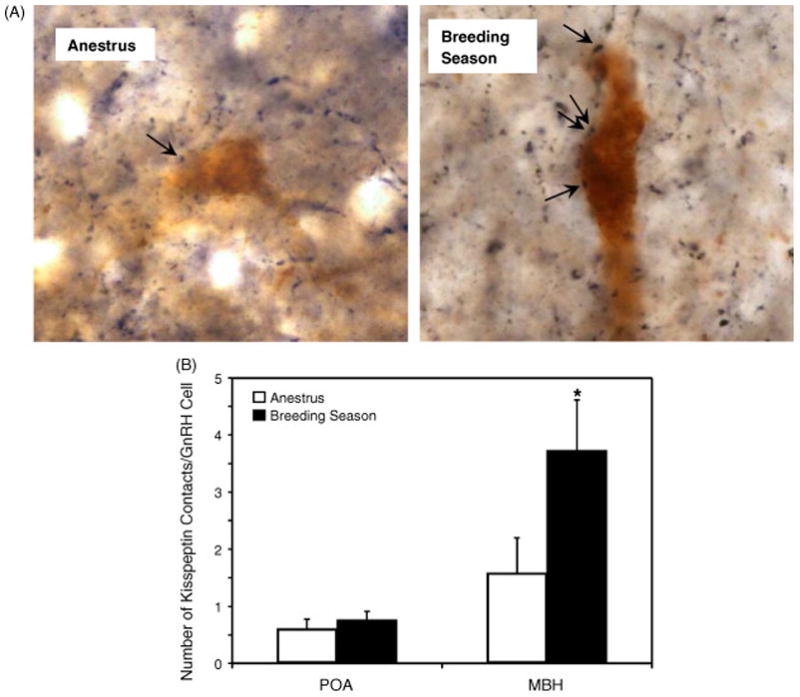

Kisspeptin cells project directly to GnRH neurons, underpinning the notion that the former are important regulators of the latter. In our recent studies of female sheep, we used dual immunocytochemistry to determine the number of kisspeptin-immunoreactive terminals that appear to directly contact GnRH cells and a clear seasonal effect was apparent. Thus, the level of kisspeptin input to GnRH neurons was higher in the breeding season than in the non-breeding season, although this was observed for the subset of GnRH cells located in the mediobasal hypothalamus and not for the subset in the preoptic area (Figure 5) [36]. The data obtained to date indicate that kisspeptin neurons are likely mediators of the seasonal change in estrogen feedback, but whether these cells are targets for melatonin is not yet known.

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of GnRH and kisspeptin double-label immunohistochemistry in the MBH of non-breeding and breeding season ewes showing kisspeptin-ir terminal (black) contacts with GnRH-ir cell bodies (brown). Arrows indicate points of contact. Panel B shows mean (± SEM) number of kisspeptin contacts per GnRH cell. *P < 0.05 non-breeding v breeding season. Adapted from Reference [36], with permission.

Pluripotent Nature of Kisspeptin Cells

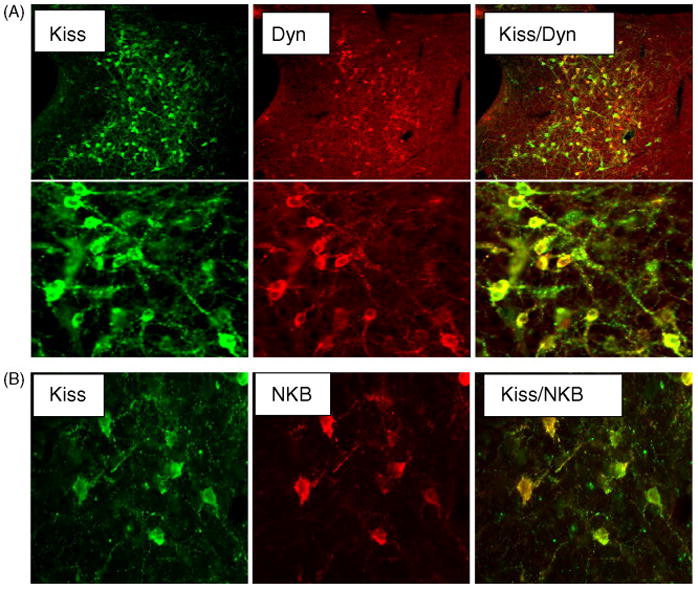

As mentioned in the introduction, GnRH cells are regulated by a wide range of systems within the brain and a number of neurotransmitters/neuropeptides are involved [38]. An interesting question, therefore, is whether kisspeptin cells co-express other neuropeptides that are known to regulate GnRH cells. In a study of the cells of the arcuate nucleus in the brains of ewes, we showed that essentially all kisspeptin cells also produce dynorphin and a very high percentage produce neurokinin B as well (Figure 6) [16]. This is relevant to the issue of seasonal breeding, since dynorphin inhibits the reproductive axis in ewes [14] and NKB has been found to have dual stimulatory and inhibitory effects [25, 31]. A very high percentage of NKB neurons were previously shown to express ERα [17] and NKB production is regulated by estrogen [28]. Dynorphin cells express both progesterone receptors and ERα [11] It is now apparent that both NKB and dynorphin are co-produced in the same cells as those that produce kisspeptin, suggesting that this single subpopulation is pivotal in feedback regulation of GnRH by estrogen. In addition, a majority of dynorphin cells of the arcuate nucleus receive synaptic input from dynorphin terminals [11], suggesting that they are reciprocally connected. The co-production of kisspeptin, dynorphin and NKB in the same cells of the arcuate nucleus raises the interesting question as to whether estrogen feedback (and/or non-steroid dependent effects of photoperiod) acts to differentially regulate the production of kisspeptin, dynorphin and NKB in these neurons.

Figure 6.

Confocal microscopic images of sections through the caudal ARC, showing kisspeptin cells that co-stain for either dynorphin (Dyn) (A) or neurokinin B (NKB) (B). The left panels show kisspeptin (green fluorescence) and the centre panels show either dynorphin (A) or NKB (B) (red fluorescence). Panels on right are computer-generated overlays of the left and middle panels. The upper panels in A are at low power and the lower panels are at a higher power to exemplify co-localisation of the two peptides. There is a high degree of co-localization of kisspeptin and dynorphin (yellow fluorescence). Adapted from Reference [16] with permission.

Restoration of Reproductive Function in the Non-Breeding Season with Kisspeptin

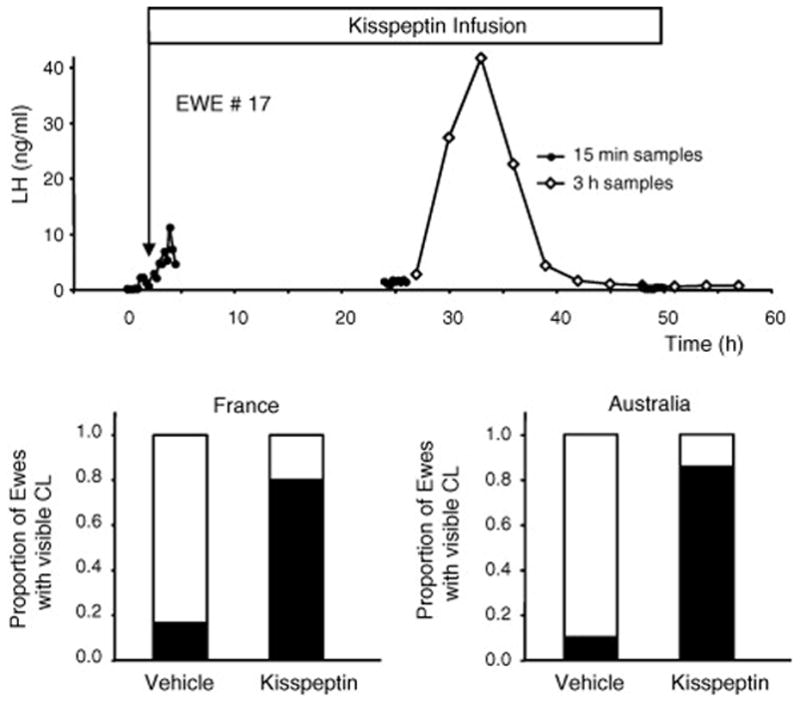

The above information strongly suggests that acyclicity in ewes during the non-breeding season is associated with reduced kisspeptin function in the arcuate nucleus. In order to determine whether kisspeptin treatment re-activates the gonadotropic axis and causes ovulation, we conducted studies in two breeds of sheep in both hemispheres. Intravenous infusion elevated gonadotropin secretion and caused ovulation [4]. In terms of mechanism, the data indicate that kisspeptin stimulated GnRH/LH secretion, simulating a follicular phase level of LH secretion that then activated the ovaries, leading to initiation of positive feedback circuits in the brain and subsequent induction of preovulatory LH surges (Figure 7). Accordingly a high percentage of the treated animals ovulated (Figure 7). One interesting question is why stimulation with kisspeptin could lead to a level of LH secretion that was sustained and not overcome by the negative feedback effect of estrogen that is pronounced in the non-breeding season. As indicated above, the possibility is that the negative feedback and positive feedback effects of estrogen may both involve kisspeptin cells and the treatment of animals with kisspeptin is distal to this, so that sustained GnRH secretion may occur with kisspeptin infusion in the anestrous season. Another interesting finding of this study was that constant infusion of kisspeptin was efficacious whereas pulsatile delivery of kisspeptin was not, an observation for which we have no ready explanation. Other work in the primate has suggested that constant infusion of kisspeptin causes downregulation of GPR54, the kisspeptin receptor [32]. Our treatment was by intravenous infusion which strongly suggests, but does not prove that kisspeptin can readily cross the blood-brain barrier. The effect of kisspeptin on the pituitary gland to regulate gonadotropin secretion seems relatively minor [37], compared to the effect in the brain to elicit GnRH release [26] The demonstration that intravenous infusion can stimulate ovulation in seasonally anestrous female sheep is consistent with findings in the hamster [33] offers a means of manipulating the reproductive axis of all seasonal mammals as well as stimulation of puberty.

Figure 7.

LH secretion and ensuing ovulation in ewes treated during the non-breeding season with an intravenous infusion of kisspeptin. The upper panel shows an example of plasma LH levels in a kisspeptin-infused ewe, indicating that the treatment led to increased secretion but the preovulatory surge did not occur until 25h later. This strongly suggests that the infusion initiated an artificial follicular phase and that the increased estrogen resulting from this activated a positive feedback response. The experiment was repeated in France and in Australia with similar results. Approximately 80% of the ewes treated with kisspeptin ovulated, as evidenced by resulting corpora lutea on the ovaries. Adapted from Reference [4] with permission.

Summary

Kisspeptin stimulates GnRH secretion and most, if not all, kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the ewe brain are estrogen responsive. Accordingly, this kisspeptin system is a prime candidate to participate in the seasonal regulation of reproduction. Evidence for this is now very compelling:-

Kisspeptin cells show changes in peptide and mRNA levels with season, consistent with a role in determining activity or quiescence of GnRH cells.

Some selective effects of estrogen are seen in kisspeptin cells in the breeding and non-breeding seasons.

Kisspeptin input to GnRH cells changes with season in a manner consistent with involvement in the determination of cyclicity

Reproductive function can be restored during the non-breeding season by kisspeptin treatment.

References

- 1.Adams VL, Goodman RL, Salm AK, Coolen LM, Karsch FJ, Lehman MN. Morphological plasticity in the neural circuitry responsible for seasonal breeding in the ewe. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4843–4851. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentley GE, Perfito N, Ukena K, Tsutsui K, Wingfield JC. Gonadotropin-inhibitory peptide in song sparrows (Melospiza melodia) in different reproductive conditions, and in house sparrows (Passer domesticus) relative to chicken-gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:794–802. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caraty A, Fabre-Nys C, Delaleu B, Locatelli A, Bruneau G, Karsch FJ, Herbison A. Evidence that the mediobasal hypothalamus is the primary site of action of estradiol in inducing the preovulatory gonadotropin releasing hormone surge in the ewe. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1752–1760. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.4.5904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caraty A, Smith JT, Lomet D, Ben Said S, Morrissey A, Cognie J, Doughton B, Baril G, Briant C, Clarke IJ. Kisspeptin synchronizes preovulatory surges in cyclical ewes and causes ovulation in seasonally acyclic ewes. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5258–5267. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke IJ. Effector mechanisms of the hypothalamus that regulate the anterior pituitary gland. In: Unsicker K, editor. The Autonomic Nervous System. Harwood; London: 1996. pp. 45–88. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke IJ. GnRH and ovarian hormone feedback. Oxf Rev Reprod Biol. 1987;9:54–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke IJ. Variable patterns of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion during the estrogen-induced luteinizing hormone surge in ovariectomized ewes. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1624–1632. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.4.8404603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke IJ, Cummins JT. Direct pituitary effects of estrogen and progesterone on gonadotropin secretion in the ovariectomized ewe. Neuroendocrinology. 1984;39:267–274. doi: 10.1159/000123990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke IJ, Cummins JT. The temporal relationship between gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion in ovariectomized ewes. Endocrinology. 1982;111:1737–1739. doi: 10.1210/endo-111-5-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke IJ, Sari IP, Qi Y, Smith JT, Parkington HC, Ubuka T, Iqbal J, Li Q, Tilbrook AJ, Morgan K, Pawson AJ, Tsutsui K, Millar RP, Bentley GE. Potent action of RFRP-3 on pituitary gonadotropes indicative of an hypophysiotropic role in the negative regulation of gonadotropin secretion. Endocrinology. 2008 doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0575. In Press, 1st July. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dufourny L, Skinner DC. Progesterone receptor, estrogen receptor alpha, and the type II glucocorticoid receptor are coexpressed in the same neurons of the ovine preoptic area and arcuate nucleus: a triple immunolabeling study. Biol Reprod. 2002;67:1605–1612. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.005066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estrada KM, Clay CM, Pompolo S, Smith JT, Clarke IJ. Elevated KiSS-1 expression in the arcuate nucleus prior to the cyclic preovulatory gonadotrophin-releasing hormone/lutenising hormone surge in the ewe suggests a stimulatory role for kisspeptin in oestrogen-positive feedback. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:806–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franceshini I, Lomet D, Cateau M, Delsol G, Tillet Y, Caraty A. Kisspeptin immunoreactive cells of the ovine preoptic area and arcuate nucleus co6express estrogen receptor alpha. Neurosci Lett. 2006;401:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman RL, Coolen LM, Anderson GM, Hardy SL, Valent M, Connors JM, Fitzgerald ME, Lehman MN. Evidence that dynorphin plays a major role in mediating progesterone negative feedback on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in sheep. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2959–2967. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman RL, Karsch FJ. Control of seasonal breeding in the ewe: Importance of changes in responses: Importance of changes in response to sex-steroid feedback. In: Reiter RJ, Follett BK, editors. Progress in Reproductive Biology, 5 Seasonal breeding in Higher Vertebrates. Karger AG; Basel: 1980. pp. 54–95. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman RL, Lehman MN, Smith JT, Coolen LM, de Oliveira CV, Jafarzadehshirazi MR, Pereira A, Iqbal J, Caraty A, Ciofi P, Clarke IJ. Kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the ewe express both dynorphin A and neurokinin B. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5752–5760. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goubillon ML, Forsdike RA, Robinson JE, Ciofi P, Caraty A, Herbison AE. Identification of neurokinin B-expressing neurons as an highly estrogen-receptive, sexually dimorphic cell group in the ovine arcuate nucleus. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4218–4225. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hazlerigg DG, Gonzalez-Brito A, Lawson W, Hastings MH, Morgan PJ. Prolonged exposure to melatonin leads to time-dependent sensitization of adenylate cyclase and down-regulates melatonin receptors in pars tuberalis cells from ovine pituitary. Endocrinology. 1993;132:285–292. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.1.7678217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karsch FJ, Dahl GE, Evans NP, Manning JM, Mayfield KP, Moenter SM, Foster DL. Seasonal changes in gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the ewe: alteration in response to the negative feedback action of estradiol. Biol Reprod. 1993;49:1377–1383. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod49.6.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinoshita M, Tsukamura H, Adachi S, Matsui H, Uenoyama Y, Iwata K, Yamada S, Inoue K, Ohtaki T, Matsumoto H, Maeda K. Involvement of central metastin in the regulation of preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge and estrous cyclicity in female rats. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4431–4436. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kriegsfeld LJ, Mei DF, Bentley GE, Ubuka T, Mason AO, Inoue K, Ukena K, Tsutsui K, Silver R. Identification and characterization of a gonadotropin-inhibitory system in the brains of mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2410–2415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511003103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legan SJ, Karsch FJ, Foster DL. The endocrin control of seasonal reproductive function in the ewe: a marked change in response to the negative feedback action of estradiol on luteinizing hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 1977;101:818–824. doi: 10.1210/endo-101-3-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehman MN, Coolen LM, Goodman RL, Viguie C, Billings HJ, Karsch FJ. Seasonal plasticity in the brain: the use of large animal models for neuroanatomical research. Reprod Suppl. 2002;59:149–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malpaux B, Tricoire H, Mailliet F, Daveau A, Migaud M, Skinner DC, Pelletier J, Chemineau P. Melatonin and seasonal reproduction: understanding the neuroendocrine mechanisms using the sheep as a model. Reprod Suppl. 2002;59:167–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McManus CJ, Valent M, Connors JM, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. A Neurokinin B agonist stimulates LH secretion in follicular, but not luteal phase, ewes. Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; 2005; Washington, USA. p. Abstract Number 760.8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Ma D, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Dixon J, Thresher RR, Malinge I, Lomet D, Carlton MB, Colledge WH, Caraty A, Aparicio SA. Kisspeptin directly stimulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone release via G protein-coupled receptor 54. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1761–1766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409330102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moenter SM, Caraty A, Karsch FJ. The estradiol-induced surge of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the ewe. Endocrinology. 1990;127:1375–1384. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-3-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pillon D, Caraty A, Fabre-Nys C, Bruneau G. Short-term effect of oestradiol on neurokinin B mRNA expression in the infundibular nucleus of ewes. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:749–753. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Revel FG, Saboureau M, Pevet P, Simonneaux V, Mikkelsen JD. RFamide-related peptide gene is a melatonin-driven photoperiodic gene. Endocrinology. 2008;149:902–912. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson JE, Radford HM, Karsch FJ. Seasonal changes in pulsatile luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion in the ewe: relationship of frequency of LH pulses to day length and response to estradiol negative feedback. Biol Reprod. 1985;33:324–334. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod33.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandoval-Guzman T, Rance NE. Central injection of senktide, an NK3 receptor agonist, or neuropeptide Y inhibits LH secretion and induces different patterns of Fos expression in the rat hypothalamus. Brain Res. 2004;1026:307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seminara SB, Dipietro MJ, Ramaswamy S, Crowley WF, Jr, Plant TM. Continuous human metastin 45–54 infusion desensitizes G protein-coupled receptor 54-induced gonadotropin-releasing hormone release monitored indirectly in the juvenile male Rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta): a finding with therapeutic implications. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2122–2126. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simonneaux V, Ansel L, Revel FG, Klosen P, Pevet P, Mikkelsen JD. Kisspeptin and the seasonal control of reproduction in hamsters. Peptides. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.06.006. This Volume. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sliwowska JH, Billings HJ, Goodman RL, Coolen LM, Lehman MN. The premammillary hypothalamic area of the ewe: anatomical characterization of a melatonin target area mediating seasonal reproduction. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1768–1775. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith JT. Sex steroid control of hypothalamic Kiss 1 expression in sheep and rodents: Comparative aspects. Peptides. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.08.013. This Volume. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith JT, Coolen LM, Kriegsfeld LJ, Sari LP, Jaafarzadehshirazi MR, Maltby M, Bateman K, Goodman RL, Tilbrook AJ, Ubuka T, Bentley GE, Clarke IJ, Lehman MN. Variation in kisspeptin and gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone expression and terminal connections to GnRH neurons in the brain: a novel medium for seasonal breeding in the sheep. Endocrinology. 2008 doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0581. In Press, 1st July. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith JT, Rao A, Pereira A, Caraty A, Millar RP, Clarke IJ. Kisspeptin is present in ovine hypophysial portal blood but does not increase during the preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge: evidence that gonadotropes are not direct targets of kisspeptin in vivo. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1951–1959. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tilbrook AJ, Turner AI, Clarke IJ. Stress and reproduction: central mechanisms and sex differences in non-rodent species. Stress. 2002;5:83–100. doi: 10.1080/10253890290027912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner GC, Johnston JD, Clarke IJ, Lincoln GA, Hazlerigg DG. Redefining the limits of day length responsiveness in a seasonal mammal. Endocrinology. 2008;149:32–39. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]