Abstract

Lytic granule exocytosis is the major pathway used by CD8+ CTL to kill virally infected and tumor cells. Despite the obvious importance of this pathway in adaptive T cell immunity, the molecular identity of enzymes involved in the regulation of this process is poorly characterized. One signal known to be critical for the regulation of granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity in CD8+ T cells is Ag receptor-induced activation of protein kinase C (PKC). However, it is not known which step of the process is regulated by PKC. In addition, it has not been determined to date which of the PKC family members is required for the regulation of lytic granule exocytosis. By combination of pharmacological inhibitors and use of mice with targeted gene deletions, we show that PKCδ is required for granule exocytosis-mediated lytic function in mouse CD8+ T cells. Our studies demonstrate that PKCδ is required for lytic granule exocytosis, but is dispensable for activation, cytokine production, and expression of cytolytic molecules in response to TCR stimulation. Importantly, defective lytic function in PKCδ-deficient cytotoxic lymphocytes is reversed by ectopic expression of PKCδ. Finally, we show that PKCδ is not involved in target cell-induced reorientation of the microtubule-organizing center, but is required for the subsequent exocytosis step, i.e., lytic granule polarization. Thus, our studies identify PKCδ as a novel and selective regulator of Ag receptor-induced lytic granule polarization in mouse CD8+ T cells.

The CD8+ CTL play a central role in adaptive immunity to tumors and intracellular pathogens. They mediate the immune response by secreting cytokines, which can be cy-totoxic and/or activate other immune cells, and by directly killing target cells using Fas-mediated or granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxic mechanisms (1, 2). Granule exocytosis is the dominant pathway used by CTL to kill tumor or virally infected cells. De-granulation releases the pore-forming protein, perforin, and several serine proteases (or granzymes) that are stored in lytic granules (3). In mouse cytolytic cells, granzymes A, B, C, D, E, F, G, K, and M have been found, but granzymes A and B are the most abundant and are currently best characterized. Effector CTL granules can be characterized as secretory lysosomes because they, in addition to the cytolytic proteins, contain lysosomal proteins, such as cathe-psins B and D, β-hexosaminidase, and lysosome-associated membrane proteins (Lamp)4 1 (CD107a), Lamp-2 (CD107b), and Lamp-3 (CD63) (4).

Subcellular events that lead to granule exocytosis in CTL are clearly defined; TCR-mediated recognition of cognate Ag on target cells induces reorientation of the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) to the plasma membrane at the point of contact with the target cell. Subsequently, lytic granules polarize toward the contact area by moving along microtubules, granules fuse with the CTL plasma membrane, and the granule contents are exposed directly to the target cell membrane (3). However, the signaling pathways and downstream effector molecules involved in the regulation of these events are not fully characterized.

TCR-induced activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and increased intracellular calcium are two signals that are known to be critical in lytic granule release (5–12). In addition to these two events, there have been only a few signaling molecules whose role in the regulation of CTL granule exocytosis is well documented. Those include PI3K and MAPK/ERK (13–19). The extent to which each of these kinases contribute to the regulation of CD8+ T cell degranulation has not been established completely, and the order in which they make their contributions to the signaling cascade leading to CTL degranulation is not known.

Despite the major role of PKC in the regulation of CTL granule exocytosis, it is not known which step of this process is regulated by PKC. In addition, it is unknown exactly which PKC isoform(s) is involved in the regulation of this cytotoxic mechanism. The PKC family has been classified into three categories: conventional (α, βI, βII, and γ), which are regulated by calcium, diacylglycerol, and phospholipids; novel (δ, ε, η, and θ), which are regulated by diacylglycerol and phospholipids, and atypical (ζ and λ), which are insensitive to both calcium and diacylglycerol (20). Therefore, we set out to determine which of the PKC isoforms is involved in the regulation of lytic granule exocytosis in CD8+ CTL, and then to determine which step of granule exocytosis is regulated by the identified isoform.

By combination of pharmacological inhibitors and use of mice with targeted gene deletions, we identified PKCδ as a positive regulator of granule exocytosis in CD8+ CTL. Our studies show that upon Ag receptor engagement, PKCδ selectively regulates the polarized movement of lytic granules toward the CTL/target cell synapse.

Materials and Methods

Mice and cells

C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from Taconic Farms. PKCδ-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background were used for the studies. PKCθ-deficient mice (C57BL/6 background) used for the studies were obtained from Dr. D. Littman (New York University Medical Center, New York, NY). 2C11 hybridoma, P815, and L1210 cells (all from American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS. Experiments using mice were performed with the permission of the Children’s National Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, protocol number 133-03-22 (S. Radoja, principal investigator). All experiments on mice were performed in accordance with the institutional and national guidelines and regulations.

Abs and reagents

Splenocytes were stimulated in vitro with culture supernatants containing anti-CD3 Ab produced by 2C11 hybridoma. CD8+ spleen T cells were purified using the magnetic bead-coupled Ab MACS system (Miltenyi Bio-tec). Purified spleen T cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 Ab, clone 2C11 (BD Pharmingen). Hamster IgG1κ (BD Pharmingen) was used as an isotype control. The same Abs were used in a redirected chromium release assay. FITC-conjugated anti-CD107a Ab or the isotype-matched control, FITC-conjugated rat IgG2a, anti-mouse CD8-allophycocyanin, CD25-PE, CD44-PE, and CD69-PE (all from BD Pharmingen) were used for the cell surface staining, followed by flow cytometry. The following Abs were used for intracellular staining: PE-conjugated anti-human gran-zyme B and mouse IgG1-PE isotype control Ab (both from Caltag Laboratories), PE-anti-mouse IFN-γ and mouse IgG1-PE isotype control Ab (both from BD Pharmingen), mouse monoclonal anti-β-tubulin Ab (Boehr-inger Mannheim), and the secondary PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG Ab (BD Pharmingen). The following Abs were used for immunoblotting: rabbit anti-mouse perforin Ab (eBioscence), HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), mouse monoclonal anti-β-tubulin Ab (Boehringer Mannheim), and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). The Lysotracker Red was used for the labeling of lysosomes in T cells, whereas Cell Tracker Blue (both from Molecular Probes) was used for labeling P815 cells. EGTA was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Chromium 51 ra-dionuclide used in the redirected cytotoxic assay was from PerkinElmer.

In vitro T cell stimulation and MLR

To generate T cell blasts, 4 × 106 total splenocytes in 4 ml of complete RPMI 1640 per well of a 6-well plate were cultured in the presence of 1% (v/v) of supernatants containing anti-CD3 Ab produced by the 2C11 hy-bridoma. After indicated periods of time, splenocytes were either stained for CD8 cell surface expression in combination with the indicated cell surface markers and analyzed by flow cytometry, or CD8+ T cells were purified by magnetic immunobeading and used as described in Results. Purity of T cells was ≥95%, as determined by flow cytometry. To generate MLR, 5 × 106 total responder splenocytes (H-2b) were mixed with an equal number of irradiated stimulator splenocytes (H-2d) in 2 ml of complete RPMI 1640 per well of a 24-well plate and were cultured for 5 days. CD8+ T cells were then isolated from the responder population by magnetic immunobeading and used in chromium release assay.

Degranulation assays

Purified CD8+ T cells were incubated for the indicated periods of time with either anti-CD3 or hamster IgG Ab immobilized on plastic (10 μg/ml Ab in 100 μl of PBS/well of a 96-well plate was incubated for 60 min or longer at 37°C) and assayed for degranulation by β-hexosaminidase release, gran-zyme A release, or Lamp-1 flow cytometric analysis. Cells (2 × 105/well) were plated in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS in 96-well plates and were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. For β-hexosaminidase assay, 50 μl of the supernatant was mixed with 150 μl of 1 mM p-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide (Sigma-Aldrich) in citrate phosphate buffer and incubated at 37°C. The reaction was stopped after 1 h by the addition of 100 μl of 1 M Na2CO3, and the absorbance at 405 nm was recorded using a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices). For the granzyme A assay, 20 μl of the supernatant was mixed with 180 μl of substrate (PBS, 0.2 mM N-benzyloxy-carbonyl-L-lysine-thiobenzylester, 0.2 mM 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)) for 30 min, and the absorbance was read at 415 nm. For both β-hexosaminidase and granzyme A, maximal release from cells was determined by treatment of cells with 1% Triton X-100, whereas spontaneous release was determined from the supernatants of cells incubated with medium only. The supernatant activity for both enzymes was expressed as a percentage of the total enzyme in Triton X-100 cell lysates. For Lamp-1 cell surface translocation, 2 × 105 cells in 200 μl of complete RPMI 1640 were stimulated for 4 h at 37°C with the plate-bound anti-CD3 or hamster IgG isotype control Ab in the presence of 10 μM monensin and 5 μg/ml FITC-conjugated anti-Lamp-1 or FITC-conjugated rat IgG2a isotype control Ab, followed by flow cytometry analysis of Lamp-1 expression in the FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Chromium release assay

The chromium release assay was performed as previously described (16). In redirected assays, anti-CD3 or hamster IgG isotype control Abs were added to the cells at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml and were present during the assay. In some assays, effectors (CTL) were preincubated for 30 min at 37°C with 1 mM sodium salt of EGTA (pH 7.5– 8.0) and addition was maintained during the 4-h lysis assay.

Conjugate formation assay

CD8+ T cells were purified from the 5-day MLRs by magnetic immuno-beading and then labeled with Lyostracker Red. Two × 105 of the labeled CD8+ T cells were mixed with 1 × 105 of Cell-Tracker Blue-labeled P815 target cells and spun at 16,000 × g for 20 s to promote conjugate formation. Cells were resuspended in 200 μl of complete RPMI 1640, incubated for 15 min at 37°C, and transferred to coverslips coated with poly-L-lysine. After 5 min of incubation at room temperature, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and conjugates were enumerated by confocal microscopy by counting the number of CD8+ T cell/P815 cell conjugates per microscopic field and the total number of CD8+ T cells in the same field. In each experiment, 100 or more CD8+ T cells were scored for conjugate formation. Percent conjugates refer to the ratio of the number of CD8+ T cells that form conjugates with P815 cells to the total number of scored CD8+ T cells, multiplied by 100%. Lyostracker Red and Cell-Tracker Blue loading was performed as described in Intracellular staining and labeling and confocal microscopy and resulted in >99% labeling of CD8+ T cells or P815 cells, respectively, as determined by flow cytometry.

Generation of PKCδ expression vector

To create the PKCδ-internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-GFP expression vector, the PKCδ gene was amplified by PCR from cDNA generated from naive CD8+ splenocytes using the primers that introduced the HindIII restriction site at the 5′ end and BamHI site after the stop codon at the 3′ end of the gene. The PCR product was cloned into HindIII-BamHI sites of the bicistronic pIRES2-AcGFP-1 plasmid vector (BD Clontech). The identity and the absence of mutations in the cloned PKCδ genes was confirmed by sequencing.

Transfection

Total resting splenocytes were stimulated in the presence of anti-CD3 Ab for 36 h and then transfected with the plasmid DNA using a nucleofection kit for primary mouse T cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Amaxa Biosystems). After nucleofection, the cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS in the absence of anti-CD3 Ab and in the presence of IL-2 for an additional 16–24 h, and then were either analyzed by flow cytometry or CD8+ T cells were purified by magnetic immunobeading and used in chromium release assays.

Immunoblotting

CTL lysates with 1 × 107 CTL/ml were prepared in Nonidet P-40 buffer (20 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 157 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 2 mM EDTA) containing complete protease inhibitors (Roche). The lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE in reducing conditions and were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Amersham Biosciences). Membranes were incubated with blocking buffer (1× TBS, 0.1% Tween 20, 5% w/v ratio nonfat dry milk) for 60 min at room temperature. Primary and secondary Abs were individually diluted in blocking buffer and were incubated with the membrane at 4°C overnight and at room temperature for 60 min, respectively. Finally, membranes were rinsed with washing buffer for five 3-min washes and exposed to SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) for 2 min.

Intracellular staining and labeling and confocal microscopy

Intracellular staining for granzyme B and IFN-γ was performed using a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, followed by flow cytometry analyses. Lysotracker Red and Cell-Tracker Blue loading was performed by incubating CD8+ T cells or P815 cells, respectively, at 37°C for 60 min with the 60 nM dye. For the assessment of MTOC- or lytic granule polarization, 2 × 105 of CD8+ T cells were mixed with an equal number of P815 target cells in 200 μl of complete RPMI 1640 containing 1 μg/ml anti-CD3 Ab. The cells were spun at 5000 rpm for 30 s, incubated for 5–15 min at 37°C, and transferred to coverslips coated with poly-L-lysine. After 5 min of incubation at room temperature, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.01% saponin and 0.5% BSA, and stained intracellularly for β-tubulin (indirect staining using mouse monoclonal anti-β-tubulin Ab followed by PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG Ab staining) or granzyme B (direct staining using PE conjugate anti-human granzyme B Ab) and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM-510 META; Zeiss).

Live imaging

Two × 105 of Lysotracker Red-labeled CD8+ CTL were mixed with an equal number of Cell-Tracker Blue-labeled target P815 cells in 200 μl of complete RPMI 1640. Anti-CD3 Ab was added to the cells at 1 μg/ml and the cells were placed in a temperature-controlled chamber (heated open superfusion chamber (RC-25F; Warner Instruments)). Preheated serum-free medium was pumped over the slices for the length of the imaging experiment and the chamber and perfusate temperature was maintained at 37°C. Sequential confocal images were acquired every 4 s for 10–15 min with a Zeiss LSM 510 META NLO system equipped with an Axiovert 200M microscope (Zeiss), with 488-nm epifluorescence and Nomarski differential interference contrast for the transmitted light. The images were processed with Zeiss LSM version 3.2 software.

Results

PKCδ is required for granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity in CD8+ T cells

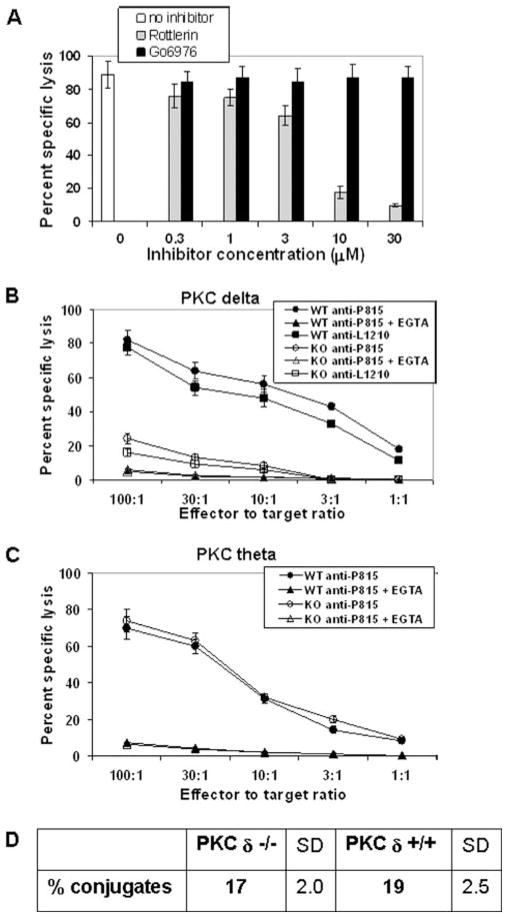

We tested the effects of Go6976, a pharmacological inhibitor of PKCα and β isoforms, and rottlerin, a pharmacological inhibitor of PKCδ and PKCθ isoforms, on cytolytic function of mouse allo-reactive CD8+ CTL. As shown in Fig. 1A, rottlerin inhibited al-loantigen-specific cytolytic activity by 50% at a concentration between 3 and 10 μM, which is close to the IC50 of this inhibitor for PKCδ and PKCθ isoforms (IC50 = 3– 6 μM). In contrast, Go6976 did not inhibit lytic activity even at 30 μM, which is well above the IC50 of this inhibitor for PKCα (IC50 = 2.3 nM) or PKCβ (IC50 = 6.2 nM). These experiments implied that PKCδ and/or PKCθ iso-forms are involved in the regulation of CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity.

FIGURE 1.

PKCδ is required for granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity of mouse CD8+ CTL. A, C57BL/6 spleen cells (H-2b) were stimulated in vitro with irradiated BALB/c splenocytes (H-2d) for 5 days. CD8+ T cells (effectors) were isolated from the responder population by magnetic immunobead-ing mixed with 51Cr-labeled target P815 cells (H-2d) at different E:T ratios and assessed for the ability to lyse the targets after 4 h of coculture in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of indicated inhibitors. Each E:T ratio was assayed in quadruplicate samples. For simplicity of the data interpretation, only the E:T of 10:1 is shown. This is a representative of four independent experiment yielding similar results. Error bars, SD. B and C, Cytolytic activity of in vitro-generated alloantigen-specific WT (H-2b) and (B) PKCδ-deficient (H-2b) or (C) PKCθ-deficient CTL (H-2b) against P815 cells, in the presence or absence of 1 mM EGTA, was tested in a 4-h chromium release assay at the indicated E:T ratios. Each E:T ratio was done in quadruplicate samples. B, In addition to P815 cells, Fas-resistant L1210 cells (H-2d) were used as targets. Data shown in B and C are representatives of five independent experiments yielding similar results. Error bars, SD. D, Quantification of conjugate formation of in vitro-generated alloantigen-specific WT (H-2b) and PKCδ-deficient (H-2b) CTL with P815 cells, as described in Materials and Methods. The mean values of three independent experiments are shown. KO, Knockout.

To validate the pharmacological inhibitor data and to determine whether both or only one of the two PKC isoforms is required for CTL cytotoxicity, we assessed alloantigen-specific cytolytic function of CTL from either PKCδ- or PKCθ-deficient mice. The chromium release assay results consistently showed that PKCδ-defi-cient CTL have significantly reduced cytolytic activity compared with wild-type (WT) CTL (Fig. 1B), while the cytotoxicity of PKCθ-deficient CTL was comparable to the activity of the control, WT CTL (Fig. 1C). Lytic activity of both WT and PKCδ-deficient CTL was almost completely inhibited by EGTA (Fig. 1B), a selective inhibitor of granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity (21). Similar results were obtained if concanamycin A, another selective inhibitor of perforin-mediated cytotoxicity, was used in the cyto-toxic assays (data not shown). When Fas-resistant L1210 cells were used as targets in the chromium release assay, cytotoxic activity of both PKCδ-deficient and WT CTL was further diminished compared with the lytic activity against the Fas-sensitive P815 cells, indicating that Fas ligand-mediated cytotoxicity is not defective in PKCδ-deficient CTL (Fig. 1B). Collectively, these experiments demonstrated that PKCδ but not PKCθ is required for lytic granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity in mouse CD8+ CTL.

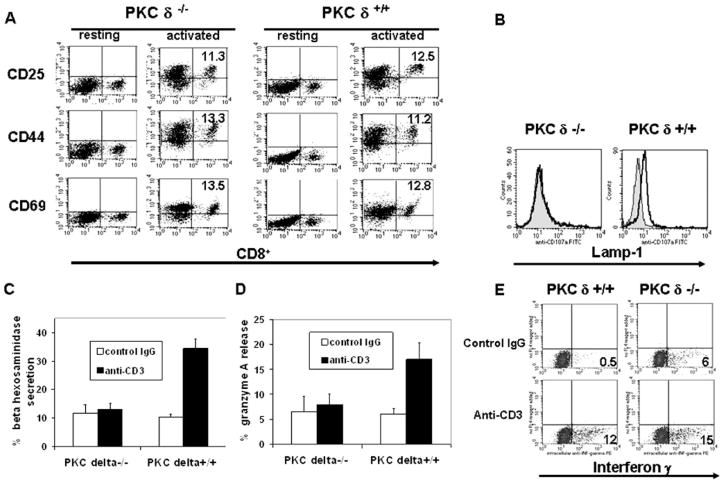

TCR-induced degranulation is defective in PKCδ-deficient CTL

PKCδ-deficient CTL showed a normal ability to form conjugates with target cells in vitro (Fig. 1D), which implied that the observed dysfunction in cytolytic activity is due to the inability of PKCδ-deficient CTL to release lytic granules. To test this, we used two TCR-induced degranulation assays: β-hexosaminidase release and increase in Lamp-1 cell surface translocation (22, 23). For this purpose, we used in vitro-activated spleen T cell blasts as CTL. In this system, in vitro culture of total spleen cells in the presence of anti-CD3 Ab results in >99% activation of CD8+ T cells from both WT and PKCδ-deficient mice, as evidenced by their forward and side scatter and their cell surface phenotype (Fig. 2A). We have previously shown that virtually all CD8+ T cells activated in this manner rapidly acquire granule exocytosis-mediated cytotox-icity (24), which facilitates the quantification of degranulation events in the given population of CTL. We used this system to compare the degranulating ability of PKCδ-deficient and WT CTL. Activated CD8+ T cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 Ab and assessed for both β-hexosaminidase release and increase in Lamp-1 cell surface translocation. As expected, these experiments demonstrated that PKCδ-deficient CTL are not able to degranulate in response to TCR ligation (Fig. 2, B and C). Also, TCR-induced exocytosis of lytic granules, as determined by gran-zyme A release, is defective in PKCδ-deficient CTL (Fig. 2D). This defect is specific, because the extent of production of IFN-γ, a major CD8+ T cell effector cytokine, in response to secondary TCR stimulation, was similar in PKCδ-deficient and WT CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 2.

TCR-induced degranulation is defective in PKCδ-deficient CD8+ T cells. Total splenocytes from WT or PKCδ-deficient mice were cultured in the presence of anti-CD3 Ab. A, After 24 h, cell surface activation marker expression on CD8+ T cells was assessed by flow cytometry. B, Purified 2-day in vitro-activated CD8+ T cells were stimulated for 4 h with plate-bound anti-CD3 (tracing) or isotype-matched control Ab (filled histogram) in the presence of 10 μM monensin and 5 μg/ml FITC-conjugated anti-Lamp-1 Ab, followed by flow cytometry analysis of Lamp-1 expression. Staining of the cells with the Lamp-1 isotype-matched control Ab resulted in the fluorescence intensity equivalent to the one observed in the unstained cells. This experiment was repeated four times, giving similar results. C and D, After 2 days of activation, CD8+ T cells were purified by magnetic immunobeading, stimulated for 4 h with the plate-bound anti-CD3- or isotype-matched control Ab and were assayed for β-hexosaminidase (C) or granzyme A (D) release in quadruplicate samples. Error bars, SD. C and D, A representative of three independent experiments is shown. In all degranulation experiments, no significant death of CD8+ T cells upon degranulation was observed, as determined by trypan blue exclusion and propidium iodide staining followed by flow cytometry. E, After 2 days of activation, CD8+ T cells were purified by magnetic immunobeading and stimulated for 4 h with plate-bound anti-CD3- or isotype-matched control Ab in the presence of brefeldin A, followed by intracellular staining for IFN-γ and flow cytometry analyses. Staining of the cells with the isotype-matched control Ab for IFN-γ resulted in the fluorescence intensity equivalent to the one observed in the unstained cells. The numbers in the flow cytometry dot plots refer to the percentage of cells in a given quadrant. A representative of three independent experiments giving similar results is shown.

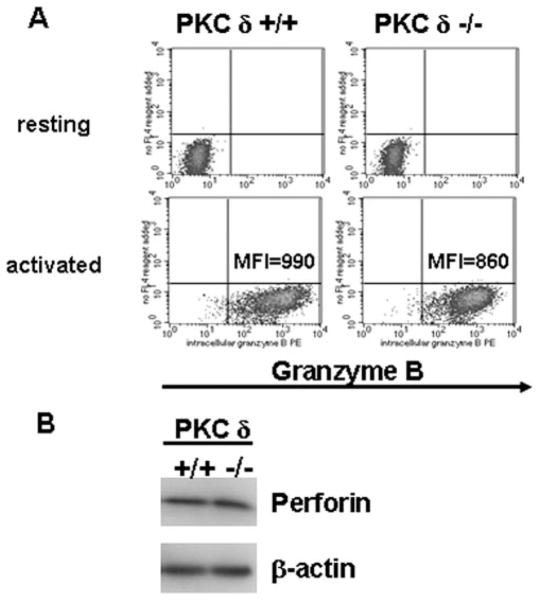

TCR-induced expression of lytic molecules is not inhibited in PKCδ-deficient CTL

The ability of the PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin to block lytic granule exocytosis demonstrates that PKCδ regulates the execution of this process in CD8+ CTL. However, this did not exclude the possibility that PKCδ may also be involved in the regulation of CTL maturation. To address this question, we assessed the levels of expression of cytolytic molecules in in vitro-generated PKCδ-de-ficient CD8+ CTL. Expression levels of both intracellular gran-zyme B (Fig. 3A) and perforin (Fig. 3B) were comparable between the PKCδ deficient and WT CTL, as determined by flow cytometry and immunoblotting, respectively, indicating that PKCδ is not required for the regulation of expression of cytolytic molecules during CTL maturation. Collectively, these results showed that, in contrast to lytic granule exocytosis, other TCR-mediated responses (activation marker cell surface expression, cytokine production, and expression of lytic molecules) are not inhibited in PKCδ-de-ficient CD8+ T cells.

FIGURE 3.

PKCδ-deficient CD8+ T cells express cytolytic molecules in response to TCR stimulation. A, Purified resting or 2-day in vitro-activated WT or PKCδ-deficient CD8+ T cells were stained intracellularly for granzyme B followed by flow cytometry. Staining of the cells with the granzyme B isotype-matched control Ab resulted in a fluorescence intensity equivalent to the one observed in the unstained cells. MFI, Mean fluorescent intensity. A representative of three independent experiments giving similar results is shown. B, Purified 2-day in vitro-activated WT or PKCδ-deficient CD8+ T cells were lysed and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using Abs specific for mouse perforin or β-actin (loading control). A representative of three independent experiments giving similar results is shown.

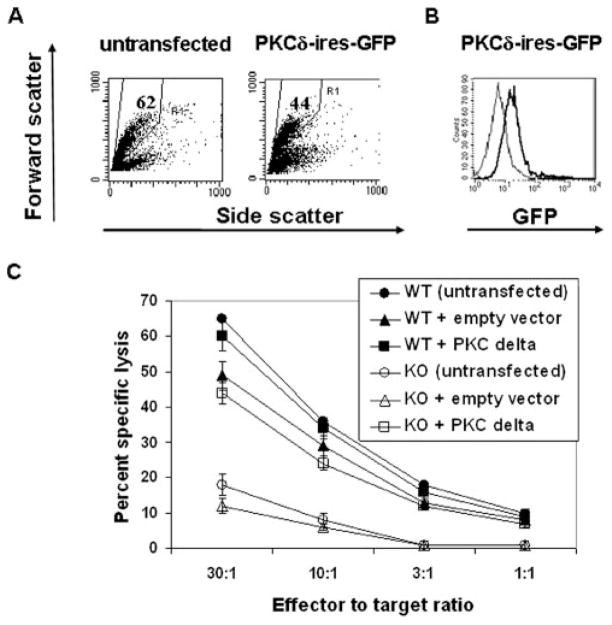

Ectopic expression of PKCδ reverses the lytic defect in PKCδ-deficient CD8+ T cells

It has been suggested that the retention of selectable marker cassettes in targeted loci can cause unexpected phenotypes in knockout mice due to the disruption of expression of neighboring genes within a locus (25). It was therefore plausible that the expression of a gene (or genes) required for lytic granule exocytosis is adversely affected in the PKCδ-deficient mice. To address these possibilities, we reconstituted PKCδ gene expression in PKCδ-defi-cient CTL. For this purpose, we cloned the full-length PKCδ gene into a bicistronic plasmid vector containing GFP under the control of IRES, positioned downstream of the CMV-driven PKCδ gene. To introduce the PKCδ gene into mature CTL, we modified nucleofection, an electroporation-based transfection method, such that we consistently achieved a high frequency of ectopic gene expression in polyclonally activated T cells. The PKCδ expression vector or the control vector was transfected into activated PKCδ-deficient or WT splenic T cells, and 16 h posttransfection, CD8+ T cells were purified and assessed for lytic function. Viability of transfected cells was ~70% that of control, non-nucleofected splenocytes, as determined by scatter analysis (Fig. 4A), trypan blue exclusion, and propidium iodide staining (data not shown). In this system, virtually the entire population of viable nucleofected T cells expressed exogenous gene, as determined by FACS analysis of GFP+ cells (Fig. 4B). As shown in Fig. 4C, the ectopic expression of PKCδ reversed defective cytolysis in PKCδ-defi-cient CD8+ CTL. Thus, these results confirmed that PKCδ is required for the execution of granule exocytosis-mediated cytotox-icity in CD8+ T cells.

FIGURE 4.

Ectopic expression of PKCδ restores cytolytic activity in PKCδ-deficient CTL. Total resting splenocytes from PKCδ-deficient mice were stimulated in the presence of anti-CD3 Ab for 36 h. A, The cells were either left untreated (untransfected), or nucleofected with the PKCδ-IRES-GFP expression vector. Sixteen to 24 h posttransfection, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Numbers in the gates in forward vs side scatter plots indicate the percentage of total cells. B, The cells were nucleo-fected with control, non-GFP coding, pcDNA3.1 plasmid vector (thin lines) or with PKCδ-IRES-GFP expression vector (thick lines). Sixteen to 24 h posttransfection, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The gated cells (A) were analyzed for GFP expression. Identical results were obtained if splenocytes from WT C57BL/6 mice were nucleofected. Representative of four independent experiments giving similar results is shown. C, WT or PKCδ-deficient splenocytes were stimulated with anti-CD3 for 36 h and then either left untreated (untransfected) or nucleofected with pIRES2-Ac-GFP1 vector (empty vector) or with PKCδ-IRES-GFP vector (PKCδ). After 16 h, CD8+ T cells were purified by magnetic immunobeading followed by a redirected 4-h chromium release assay against P815 cells. Each E:T ratio was done in triplicate samples. A representative of three independent experiments giving similar results is shown. Error bars, SD. KO, Knockout.

PKCδ regulates Ag receptor-induced lytic granule polarization in CD8+ T cells

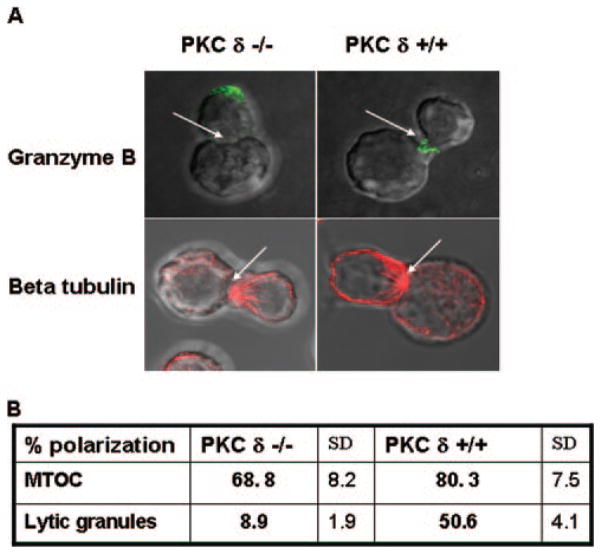

To determine exactly which step of lytic granule exocytosis is regulated by PKCδ, we assessed MTOC reorientation and lytic granule polarization in PKCδ-deficient CTL after target cell recognition. WT- or PKCδ-deficient allospecific CTL were allowed to form conjugates with target cells, followed by intracellular staining for β-tubulin or granzyme B, which enabled the visualization of MTOC and lytic granules, respectively. Target cell-induced polarization of MTOC or lytic granules was analyzed by confocal microscopy. We consistently observed that PKCδ-defi-cient CTL efficiently reorient MTOC in response to target cell recognition (Fig. 5). In a marked difference, PKCδ-deficient CTL were not able to polarize lytic granules toward the contact site with target cells (Fig. 5). The inability of PKCδ-deficient CTL to polarize lytic granules was confirmed by live imaging experiments in which the target cell recognition-induced polarization of lysosomal granules in the WT- or PKCδ-deficient CTL was monitored by two-photon live cell microscopy (supplemental video 1: lysosomal granule polarization in live WT CTL responding to target cell recognition and supplemental video 2: lysosomal granule polarization in live PKCδ-deficient CTL responding to target cell recognition).5 Collectively, these results demonstrated that PKC δ is dispensable for Ag receptor induced MTOC reorientation, but is required for the subsequent lytic granule exocytosis step that is lytic granule polarization.

FIGURE 5.

PKCδ regulates lytic granule polarization in CTL responding to target cell recognition. A, CD8+ T cells purified by magnetic im-munobeading from WT or PKCδ-deficient mouse splenocytes activated in vitro with anti-CD3 Ab for 2 days were allowed to form conjugates with P815 cells for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of anti-CD3 Ab. The cells were transferred to coverslips, stained intracellularly for β- tubulin or gran-zyme B as described in Materials and Methods, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Arrowheads, CTL/target cells synapse. A representative from three independent experiments is shown. B, Quantification of MTOC and lytic granule polarization frequencies in WT or PKCδ-deficient CTL responding to target cell recognition. Percent polarization refers to the ratio of the number of CTL that polarize MTOC/lytic granules to the total number of scored conjugates, multiplied by 100%. The mean values of four independent experiments are shown. In each experiment, 40 or more CTL target cell conjugates were scored for the polarization of MTOC or lytic granules toward the contact sites.

Discussion

There are several important findings resulting from this study. First, we identified PKCδ as a novel regulator of lytic granule exocytosis in mouse CD8+ CTL. Second, we showed that PKCδ is a specific and selective inducer of this effector function in T cells. (This is a first report of selective regulation of the cytotoxic effector function in CTL by a kinase.) Third, before our work, PKCδ was shown only to be a negative regulator of Ag receptor-mediated responses in immune cells. We now demonstrate that PKCδ is a positive regulator of an effector function in T lymphocytes.

Before our work, only two molecules (Rab27a and α subunit of Rab geranylgeranyl transferase (RGGTA)) had been reported to specifically regulate lytic granule exocytosis in mouse CD8+ CTL. Rab27a regulates the distal stages of TCR-induced lytic granule exocytosis and lytic granule movement from microtubules to the plasma membrane following granule polarization toward the target cell contact site (22, 26). Similar to what we found with PKCδ, it was demonstrated that Rab27a is not required for other TCR-mediated functions in mouse T cells, including cytokine production, lytic molecule expression, and Fas ligand expression. Phenotypes of Rab27a and PKCδ-deficient CTL, however, show that the two molecules regulate temporally and spatially distinct stages of lytic granule exocytosis. This is based on the fact that Rab27a regulates granule exocytosis at the stage of the detachment of lytic granules from microtubules, after lytic granule polarization had occurred. Our data clearly show that PKCδ regulates lytic granule polarization, a step that precedes the one regulated by Rab27a. Thus, this implies that PKCδ is placed upstream of Rab27a in the process of the regulation of lytic granule exocytosis. However, one cannot exclude the possibility that PKCδ regulates more than one stage of this process. PKCδ could potentially interact with Rab27a and/or modulate its function (e.g., recruitment of other molecule(s) involved in regulation of granule exocytosis).

The function of RGGTA is prenylation of a subset of Rab proteins, a posttranslational modification that allows the targeting of Rab proteins to intracellular membrane compartments, including lysosomal granules (27). Consequently, CTL from mice with diminished RGGTA activity (gunmetal mice) have defective granule exocytosis due to the inability of lytic granules to polarize toward the target cell contact site (26). Therefore, RGGTA and PKCδ regulate the same step of the process of lytic granule exocytosis. The roles of the two molecules in the regulation of this stage of granule exocytosis are, however, likely to be different. The role of RGGTA is probably indirect, as it was proposed that it prenylates a yet-unidentified Rab molecule(s) involved in regulation of lytic granule polarization (26).

Mutations in the Lyst gene, found in patients with Chediak-Higashi syndrome and its mouse model, the beige mouse, also result in defective granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity (28, 29). LYST protein is not directly involved in granule exocytosis, but it regulates lysosomal biogenesis/membrane fusion. As a consequence, LYST-deficient cells have abnormally enlarged lysoso-mal granules. It has been shown that CTL from Chediak-Higashi syndrome patients have defective cytotoxicity, due to the inability to release lysosomal granules upon TCR engagement (30). Mouse CTL lacking LYST probably have the same phenotype, but detailed phenotypic analyses of CTL from the beige mice have not been reported to date. Based on the function of LYST protein, it is likely that LYST deficiency results specifically in defective granule exocytosis and that it does not affect the other TCR-induced responses. However, there is currently no published data to support this assumption.

Other molecules that are established to have a role in the regulation of granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity in mouse CD8+ T cells are ERK1/2 and PI3K (13–19). These kinases are components of general TCR-mediated signaling cascade and are, in addition to the regulation of lytic function, involved in control of the other aspects of T cell function, including activation, proliferation, differentiation, and cytokine production (31). Previous studies (32, 33) and our work presented in this study indicate that PKCδ does not have a major role in positive regulation of these functions. In the present work, we show that PKCδ is required for Ag receptor-induced granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity in CD8+ T cells. Thus, PKCδ is the first kinase demonstrated to specifically regulate lytic function in CTL. This further suggests that PKCδ might be a component of the TCR-induced signaling pathway(s) that selectively regulates CTL cytotoxicity. Indications that the cytotoxicity-specific TCR pathway exists initially came from the studies describing split anergy in CD8+ T cells, characterized by the retention of lytic function, despite an inability to proliferate and produce cytokines in response to TCR stimulation (34, 35). However, molecular constituents of such a pathway remained uncharacterized to date. Identification of upstream and/or downstream PKCδ effectors in the future studies might allow the characterization of TCR signaling pathway(s) that selectively regulates granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity in CD8+ T cells.

Before our study, PKCδ was considered to be a negative regulator of Ag receptor-mediated responses in immune cells (20). In B cells, PKCδ regulates negative feedback important for immune homeostasis and prevention of autoimmune disease (33, 36). In mast cells, it inhibits Ag-receptor induced degranulation (37). Previous work suggested that PKCδ plays a role in the negative regulation of IL-2 cytokine production and proliferation in T cells (32). The work presented in this study demonstrates for the first time a role of PKCδ in the positive regulation of an Ag receptor-mediated function, that is lytic granule exocytosis, in immune cells. In contrast, positive regulation by PKCδ of stimulus-induced granule secretion has been described in nonimmune cell types. PKCδ was proposed to have a role in the induction of dense granule and insulin secretion in platelets and pancreatic β cells, respectively (38, 39). Interestingly, depending on the type of stimulus, PKC serves either as a positive or as a negative regulator of dense granule secretion in platelets. Similarly, in T cells, PKCδ attenuates proliferation and IL-2 secretion, but induces lytic granule exocytosis upon TCR engagement. Thus, PKCδ can act either as a positive or as a negative regulator of cellular responses, depending on the cell type and/or its selective interaction with distinct effectors within the same cell.

Another interesting aspect of our study is that PKCδ and PKCθ, two closely related members of the same subfamily of calcium-independent PKC, have specific and nonredundant functions in T cells. In direct contrast to PKCδ, PKCθ has been shown to have an important role in T cell activation, including the proliferation and IL-2 production in T cells (40). Recently, contradictory findings have been reported concerning the involvement of PKCθ in in vitro cytotoxic function of human and mouse CD8+ T cell clones/ lines (10–12). Our results now unequivocally show that (in contrast to PKCδ-deficient CD8+ T cells) primary CD8+ CTL from PKCθ-deficient mice do not have defective granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity in vitro.

Identification of PKCδ as a selective inducer of lytic granule exocytosis significantly advances our knowledge regarding the regulation of this T cell effector function. Determination of the exact mechanism of action of PKCδ and identification of PKCδ effectors in the future studies will further help the delineation of the TCR-induced regulatory pathway of lytic granule exocytosis. The knowledge gained by these studies might potentially allow selective manipulation of cytolytic activity by specifically modifying the function of PKCδ and/or its molecular partners. This, in turn, could enable the selective tuning of granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells in disease.

There has been increasing evidence in the literature that the dysregulation of granule exocytosis-mediated cytotoxicity in CD8+ CTL has a crucial role in initiation of familial hemophago-cytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL), a rare, fatal pediatric immune disorder (41). To date, mutations in the perforin (42), Munc 13-4 (43), and syntaxin 11 (44) genes have been shown to be associated with FHL2, FHL3, and FHL4 subtypes, respectively. Genetic defects responsible for the pathogenesis of the remaining FHL (some estimated 45–50% of the cases, excluding FLH4, for which the corresponding data are not yet available) have not be determined to date (45).

Thus, discovery of novel genes that regulate lytic granule release might potentially lead to the identification of the gene(s) responsible for pathogenesis of the remaining FLH subtype(s). The use of mouse models for such studies is of particular importance because the majority of the genes identified so far to be required for lytic granule exocytosis in mouse CTL have been demonstrated to have equivalent functions in human CTL. Furthermore, mutations in some of these genes (i.e., perforin, Rab27a, and Lyst) result in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like syndromes in humans (4, 41). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that PKCδ might be involved in regulation of FHL. Future studies concerning the requirement of PKCδ for lytic function in human CD8+ CTL and/or assessment of the functional status of PKCδ in CTL from FHL patients will address this possibility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dan Littman, New York University Medical Center, for providing PKCθ-deficient mice. We also thank Daniela Pappini for the assistance with flow cytometry analyses.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA108573 (to A.B.F.), National Institutes of Health Grant F32CA101449-02 Award and Research Advisory Council Grant (to S.R.), and National Institutes of Health Grants R01AI48837 and R01AI41573 (to S.V.).

Abbreviations used in this paper: MTOC, microtubule-organizing center; PKC, protein kinase C; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; WT, wild type; RGGTA, Rab geranylgeranyl transferase; FHL, familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Russell JH, Ley TJ. Lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:323–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100201.131730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kagi D, Ledermann B, Burki K, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity and their role in immunological protection and pathogenesis in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:207–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry M, Bleackley R. Cytotoxic lymphocytes: all roads lead to death. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nri819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blott EJ, Griffiths GM. Secretory lysosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:122–131. doi: 10.1038/nrm732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancki DW, Weiss A, Fitch FW. Requirements for triggering of lysis by cytolytic T lymphocyte clones. J Immunol. 1987;138:3646–3653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juszczak RJ, Russell JH. Inhibition of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated lysis and cellular proliferation by isoquinoline sulfonamide protein kinase inhibitors: evidence for the involvement of protein kinase C in lymphocyte function. J Biol Chem. 1989;254:810–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nesic D, Jhaver KG, Vukmanovic S. The role of protein kinase C in CD8+ T lymphocyte effector responses. J Immunol. 1997;159:582–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sitkovsky MV. Mechanistic, functional and immunopharmacological implications of biochemical studies of antigen receptor-triggered cytolytic T-lymphocyte activation. Immunol Rev. 1988;103:127–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1988.tb00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esser MT, Haverstick DM, Fuller CL, Gullo CA, Braciale VL. Ca2+ signaling modulates cytolytic T lymphocyte effector functions. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1057–1067. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardo J, Buferne M, Martinez-Lorenzo MJ, Naval J, Schmitt-Verhulst AM, Boyer C, Anel A. Differential implication of protein kinase C iso-forms in cytotoxic T lymphocyte degranulation and TCR-induced Fas ligand expression. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1441–1450. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puente LG, He JS, Ostergaard HL. A novel PKC regulates ERK activation and degranulation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes: plasticity in PKC regulation of ERK. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1009–1018. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grybko MJ, Pores-Fernando AT, Wurth GA, Zweifach A. Protein kinase C activity is required for cytotoxic T cell lytic granule exocytosis, but the θ isoform does not play a preferential role. J Leukocyte Biol. 2007;81:509–519. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0206109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowin-Kropf B, V, Shapiro S, Weiss A. Cytoskeletal polarization of T cells is regulated by an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-dependent mechanism. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:861–871. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller CL, Ravichandran KS, Braciale VL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent and -independent cytolytic effector functions. J Immunol. 1999;162:6337–6340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robertson LK, Mireau LR, Ostergaard HL. A role for phos-phatidylinositol 3-kinase in TCR-stimulated ERK activation leading to paxillin phosphorylation and CTL degranulation. J Immunol. 2005;175:8138–8145. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radoja S, Saio M, Schaer D, Koneru M, Vukmanovic S, Frey AB. CD8+ tumor-infiltrating T cells are deficient in perforin-mediated cytolytic activity due to defective microtubule-organizing center mobilization and lytic granule exocytosis. J Immunol. 2001;167:5042–5051. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berg NN, Puente LG, Dawicki W, Ostergaard HL. Sustained TCR signaling is required for mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and degranulation by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:2919–2924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lilic M, Kulig K, Messaoudi I, Remus K, Jankovic M, Nikolic-Zugic J, Vukmanovic S. CD8+ T cell cytolytic activity independent of mitogen-activated protein kinase / extracellular regulatory kinase signaling (MAP kinase/ ERK) Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3971–3977. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<3971::AID-IMMU3971>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fierro AF, Wurth GA, Zweifach A. Cross-talk with Ca2+ influx does not underlie the role of extracellular signal-regulated kinases in cytotoxic T lymphocyte lytic granule exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25646–25652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitaler M, Cantrell DA. Protein kinase C and beyond. Nat Immun. 2004;5:785–790. doi: 10.1038/ni1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacLennan IC, Gotch FM, Golstein P. Limited specific T-cell mediated cytolysis in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ Immunology. 1980;39:109–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haddad EK, Wu X, Hammer JA, III, Henkart PA. Defective granule exocytosis in Rab27a-deficient lymphocytes from Ashen mice. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:835–842. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubio V, Stuge TB, Singh N, Betts MR, Weber JS, Roederer M, Lee PP. Ex vivo identification, isolation and analysis of tumor-cytolytic T cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:1377–1382. doi: 10.1038/nm942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen DT, Ma JSY, Mather J, Vukmanovic S, Radoja S. Activation of primary T lymphocytes results in lysosome development and polarized granule exocytosis in both CD4+ and CD8+ subset whereas expression of lytic molecules confers cytotoxicity to CD8+ T cells. J Leukocyte Biol. 2006;80:827–837. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pham CT, MacIvor DM, Hug BA, Heusel JW, Ley TJ. Long-range disruption of gene expression by a selectable marker cassette. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13090–13095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stinchcombe JC, Barral DC, Mules EH, Booth S, Hume AN, Machesky LM, Seabra MC, Griffiths GM. Rab27a is required for regulated secretion in cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:825–834. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seabra MC, Wasmeier C. Controlling the location and activation of Rab GTPases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein M, Roder J, Haliotis T, Korec S, Jett JR, Herberman RB, Katz P, Fauci AS. Chediak-Higashi gene in humans, II: the selectivity of the defect in natural-killer and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function. J Exp Med. 1980;151:1049–1058. doi: 10.1084/jem.151.5.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biron CA, Pedersen KF, Welsh RM. Aberrant T cells in beige mutant mice. J Immunol. 1987;138:2050–2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baetz K, Isaaz S, Griffiths GM. Loss of cytotoxic T lymphocyte function in Chediak-Higashi syndrome arises from a secretory defect that prevents lytic granule exocytosis. J Immunol. 1995;154:6122–6131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radoja S, Frey AB, Vukmanovic S. T cell receptor signaling events triggering granule exocytosis. Crit Rev Immunol. 2006;26:265–290. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v26.i3.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruber T, Barsig J, Pfeifhofer C, Ghaffari-Tabrizi N, Tinhofer I, Leitges M, Baier G. PKCδ is involved in signal attenuation in CD3+ T cells. Immunol Lett. 2005;96:291–293. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyamoto A, Nakayama K, Imaki H, Hirose S, Jiang Y, Abe M, Tsukiyama T, Nagahama H, Ohno S, Hatakeyama S, Nakayama KI. Increased proliferation of B cells and auto-immunity in mice lacking protein kinase Cδ. Nature. 2002;416:865–869. doi: 10.1038/416865a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otten GR, Germain RN. Split anergy in a CD8+ T cell: receptor-dependent cytolysis in the absence of interleukin-2 production. Science. 1991;251:1228–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.1900952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jhaver KG, Rao TD, Frey AB, Vukmanovic S. Apparent split tolerance of CD8+ T cells from β 2-microglobulin-deficient (β2m−/−) mice to syngeneic β 2m+/+ cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:6252–6261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mecklenbrauker I, Saijo K, Zheng NY, Leitges M, Tarakhovsky A. Protein kinase Cδ controls self-antigen-induced B-cell tolerance. Nature. 2002;416:860–865. doi: 10.1038/416860a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leitges M, Gimborn K, Elis W, Kalesnikoff J, Hughes MR, Krystal G, Huber M. Protein kinase C-δ is a negative regulator of antigen-induced mast cell degranulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3970–3980. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.3970-3980.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murugappan S, Tuluc F, Dorsam RT, Shankar H, Kunapuli SP. Differential role of protein kinase C δ isoform in agonist-induced dense granule secretion in human platelets. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2360–2367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uchida T, Iwashita N, Ohara-Imaizumi M, Ogihara T, Nagai S, Choi JB, Tamura Y, Tada N, Kawamori R, Nakayama K, et al. PKC-δ plays non-redundant role in insulin secretion in pancreatic β cell. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2707–2716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arendt CW, Albrecht B, Soos TJ, Littman DR. Protein kinase C-θ: signaling from the center of the T-cell synapse. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:323–330. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menasche G, Feldmann J, Fischer A, de Saint Basile G. Primary hemophagocytic syndromes point to a direct link between lymphocyte cytotox-icity and homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2005;203:165–179. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stepp SE, Dufourcq-Lagelouse R, Le Deist F, Bhawan S, Certain S, Mathew PA, Henter JI, Bennett M, Fischer A, de Saint Basile G, Kumar V. Perforin gene defects in familial hemophagocytic lymphohis-tiocytosis. Science. 1999;286:1957–1959. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feldmann J, Callebaut I, Raposo G, Certain S, Bacq D, Dumont C, Lambert N, Ouachee-Chardin M, Chedeville G, Tamary H, et al. Munc13-4 is essential for cytolytic granules fusion and is mutated in a form of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL3) Cell. 2003;14:461–473. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.zur Stadt U, Schmidt S, Kasper B, Beutel K, Diler AS, Henter JI, Kabisch H, Schneppenheim R, Nurnberg P, Janka G, Hennies HC. Linkage of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL) type-4 to chromosome 6q24 and identification of mutations in syntaxin 11. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;15:827–834. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishii E, Ohga S, Imashuku S, Kimura N, Ueda I, Morimoto A, Yamamoto K, Yasukawa M. Review of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in children with focus on Japanese experiences. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;53:209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.