Abstract

CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) lack in vivo and in vitro lytic function due to a signaling deficit characterized by failure to flux calcium or activate tyrosine kinase activity upon contact with cognate tumor cells. Although CD3ζ is phosphorylated by conjugation in vitro with cognate tumor cells, showing that TIL are triggered, PLCγ-1, LAT, and ZAP70 are not activated and LFA-1 is not affinity-matured, and because p56lck is required for LFA-1 activation, this implies that the signaling blockade is very proximal. Here, we show that TIL signaling defects are transient, being reversed upon purification and brief culture in vitro, implying a fast-acting “switch”. Biochemical analysis of purified nonlytic TIL shows that contact with tumor cells causes transient activation of p56lck (~10 s) which is rapidly inactivated. In contrast, tumor-induced activation of p56lck in lytic TIL is sustained coincident with downstream TCR signaling and lytic function. Shp-1 is robustly active in nonlytic TIL compared with lytic TIL, colocalizes with p56lck in nonlytic TIL, and inhibition of Shp-1 activity in lytic TIL in vitro blocks tumor-induced defective TIL cytolysis. Collectively, our data support the notion that contact of nonlytic TIL with tumor cells, and not with tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells, causes activation of Shp-1 that rapidly dephosphorylates the p56lck activation motif (Y394), thus inhibiting effector phase functions.

Introduction

Although variable in the magnitude of response, cancers have been conclusively shown to be immunogenic (1). Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) accumulate in tumors which contain differentiated, antigen-specific T cells (2–4) supporting the notion that tumor growth results in the priming of antitumor T cells. Cancer patients also produce circulating antitumor IgG which has been used to identify new tumor antigens (5). Tumor-specific T cells can home to and accumulate in tumors, as evidenced by experiments using transgenic mice expressing a TCR specific for a cognate antigen (6). In addition, some tumors have been shown to regress spontaneously as well as in response to vaccine therapy or adoptive immunotherapy demonstrating the active role of the immune system in controlling tumor growth (7). Nevertheless, spontaneous tumor remission is rare and the 5-year survival rate of patients receiving experimental immunotherapy has been estimated by Rosenberg to be <5%, with most patients eventually relapsing. The failure to eliminate antigenic cancers shows tumor immune evasion and several potential mechanisms of escape have received experimental support (8).

There are various postulated mechanisms of tumor escape, implicating multiple phases of the immune response. In a study of tumor immune evasion using multiple model systems, one consistent observation is that TIL are deficient in effector phase functions, implying tumor-induced suppression within the tumor microenvironment. The observation that human TIL are antigen-specific but nonlytic (4), together with our description of the defective lytic function of murine TIL (9) and the lack of systemic suppression of the immune system in tumor-bearing mice (10), supports the notion that tumor-induced inhibition of TIL lytic function is common and might contribute to cancer growth in spite of antitumor immune response. Freshly isolated TIL are nonlytic memory/effector cells (11) but recover lytic function following brief in vitro culture permitting direct comparison of lytic and nonlytic TIL purified from the same tumor. Because cytolysis is dependent on TCR-mediated signaling and TIL are unable to exocytose lytic granules (9, 12), we considered that the residence of antitumor T cells in the tumor microenvironment induces defective signal transduction. Supporting this notion, when conjugated with cognate tumor cells in vitro, signal transduction in nonlytic TIL is blocked such that tyrosine kinase activity is weak and calcium flux is abrogated (9), deficiencies that undoubtedly underlie lytic dysfunction.

Using a murine model of colon carcinoma, MCA38, we show herein that tumor cells (and not host tumor-infiltrating stromal cells, soluble factors, or regulatory T cells) are responsible for the induction of defective TIL proximal signaling defects. Inhibition of TCR signaling is manifested by the failure to activate ZAP70 (9) and involves activation and recruitment to the immune synapse of the protein tyrosine phosphatase Shp-1, which inactivates p56lck, the most proximal tyrosine kinase in the TCR signaling cascade, therein effectively blocking all downstream signaling in TILs and inhibiting effector phase functions.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 male mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory, and used as described previously (9, 13). Experiments involving animals were conducted with the approval of the New York University School of Medicine Committee on Animal Research.

Tumors

MCA38 adenocarcinoma (provided by N. Restifo, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) was passaged by incubation in HBSS containing 3 mmol/L of EDTA. Viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion, and 0.1 to 0.3 × 106 cells were injected i.p. in HBSS. Cells were passaged in vitro for 3 to 5 weeks, following which new frozen stocks were thawed for usage.

Tissue culture

RPMI 1640 (Bio Whittaker) was used for the growth of tumor cell lines and for the culture of T cells as described (13).

Isolation of TIL

TIL were isolated as described previously (12). In each experiment, aliquots of isolated T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and were routinely ~95% CD8+.

Isolation of tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells

Single cell suspensions of tumors were prepared and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) were isolated by immunomagnetic separation as described previously (14).

Coculture of primary tumor cells/tumor cell lines and TIL

Cells (2 × 106) from the total primary tumor or different tumor cell lines were cocultured with 1 × 106 nonlytic or lytic CD8+ TIL in 12-well plates with 4 mL of complete medium per well. At different times following coculture (1–16 h), TIL were recovered by harvesting and repurification on a column (without additional anti-CD8 beads). For coculture experiments in trans-well plates, 2 × 106 cells of total primary tumor or different tumor cell lines were cultured in the bottom chamber and 1 × 106 nonlytic or lytic CD8+ TIL were cultured in the transwell insert.

Antibodies

Antibodies were used as described except CD3ζ (rabbit IgG; D. Wiest, Fox Chase Cancer Institute, Philadelphia, PA), iNOS/NOS type II (clone pAB; BD Transduction Laboratories), Shp-1 (rabbit IgG; Upstate USA), Shp-2 (clone sc280; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Csk (rabbit IgG, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), pErk (rabbit IgG; Cell Signaling), phosphotyrosine (clone 4G10; Upstate), phospho-p56lck Y505, and phospho-p56lck Y394 (rabbit IgG; A. Shaw, Washington University, St. Louis, MO).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analyses and conjugate formation and confocal microscopy were performed as described (9). More than 50 conjugates were analyzed for each confocal experiment. The percentage of conjugates showing a specific phenotype is shown in the legends to corresponding micrographs for each confocal analysis (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Figs. S2, S4, and S5).

Figure 5.

Shp-1 is activated in nonlytic TIL. A, localization of Shp-1 and pErk in nonlytic TIL and lytic TIL. TIL/tumor conjugates were formed for 2.5 min and assessed for protein localization by confocal microscopy as described (9). Arrows, TIL/tumor cell contact site. Thirty-six percent of nonlytic TIL conjugates show Shp-1 localization at the contact site compared with only 13% in lytic TIL conjugates. This experiment was performed more than five times with equivalent results. B, phosphorylation status of Shp-1 in nonlytic TIL and lytic TIL. Nonlytic TIL were isolated from MCA38 tumors and a portion was allowed to recover lytic function in vitro as described previously. Both TIL samples were detergent-extracted and immunoprecipitated with anti–Shp-1 (0.002 mg per sample). Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using antiphosphotyrosine or anti–Shp-1. Blots were exposed to X-ray films for different times in order to record images of different band saturations; films were scanned as described above. There was 300% (3×) more tyrosine-phosphorylated Shp-1 in nonlytic TIL compared with lytic TIL. This experiment was performed more than five times with equivalent results. C, phosphatase activity of Shp-1. Shp-1 protein was antibody-captured from cell lysates of nonlytic and lytic TIL (or as controls, HL60 cells and MCA38 cells) and production of p-nitrophenolate ion was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Shp-1 activity was determined from MCA38 cells using a number of tumor cells in the approximate range of potential contamination (1–5%). This experiment was performed thrice with equivalent results.

Chromium release assay

The cytolytic activity of TIL was determined in standard 51Cr release assays as previously described (9, 12), and the formula used for the determination of specific lysis was [(experimental release × spontaneous release)/(maximal release × spontaneous release)]/100.

Nitrite assay

Nitric oxide production was assayed in supernatants collected from replicate wells of primary tumor cultures, tumor cell lines, and cocultures of tumor cell lines and TIL by the method of Griess (15). Supernatant (0.1 mL) was mixed with 0.01 mL of Griess reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min at room temperature and A550 nm was recorded. Nitrite concentration was determined using NaNO2 as a standard curve.

Urea assay

Arginase activity was assayed in cells by the modified Schimke method (16). Cells were harvested, washed with PBS, lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100–containing protease inhibitors (0.01 mg/mL each of aprotinin, antipain, and pepstatin) at 2 × 105 to 106/0.05 mL and mixed at room temperature for 30 min. Equal volumes of 10 mmol/L of MnCl2 and 50 mmol/L of Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) were added before heating (55°C for 10 min). Subsequently, 0.025 mL of 0.5 mol/L arginine (pH 9.7) was added to equal volumes of lysate, incubated at 37°C for 60 min and the reaction stopped with 0.4 mL of a 1:3:7 mixture of H2SO4/H3PO4/H2O. Finally, 0.025 mL of 9% 1-phenyl-1,2-propanedione-2-oxime (in ethanol) was added, heated at 95°C for 30 min, cooled at room temperature in the dark for 10 min before A540 nm was recorded. A standard curve was made using urea dissolved in cell lysis buffer.

Analysis of Shp-1 phosphatase activity

Shp-1 activity was determined by immunoprecipitation of Shp-1 from TIL (or positive control HL60 or negative control MCA38 cells) and reaction with pNPP as substrate (17). Cells were lysed in NP40 lysis buffer, centrifuged to prepare cleared cell lysates, 0.001 mg anti–Shp-1 (or control IgG) were added (2 h at 4°C), immunocomplexes were isolated by the addition of 0.015 mL of protein G-Sepharose (1 h at 4°C), beads were washed in phosphatase assay buffer, pNPP was added (0.5 mmol/L), and A405 nm recorded at 30 min.

Preparation of vector expressing dnShp-1

Plasmids containing either a deletion allele (17) or a point mutation (active site Cys-Ser) dominant-negative of Shp-1 (“MDSCV-SHP-1δP” or “SHP Cys-Ser”, both provided by U. Lorenz, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA), or the “empty” vector, was cotransfected with a plasmid expressing packaging functions (“pCI-VSV-G”, provided by B. Schneider, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY) into 293GP cells. Thirty-six hours later, producer cells were cocultured with TIL following which TIL were isolated by magnetic immunobeading.

Short interfering RNA silencing in TIL

The Shp-1 cDNA sequence: 5′-aacgc agctg acatt gagaat-3′ (GenBank AK 132509)1 was targeted (this sequence was successfully targeted in human models; refs. 18, 19). Short interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes were created using 5′-cgc agcug acauu gagaaudtdt-3′ and antisense 3-dtdtgcg ucgac uguaa cucuua-5′ (InvitroGen, Inc.). 0.002 mg Shp-1 siRNA (or the equivalent amount of control siRNA; Ambion) was transfected into 106 TIL in 0.3 mL using Hiperfect (InvitroGen). Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were harvested and used in “reversion” assays as described above. The effectiveness of siRNA silencing was also assessed by immunoblotting TIL total protein detergent extracts. Following blotting with anti–Shp-1, blots were stripped and reprobed with anti–Shp-2.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as described (12) and blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Roche Diagnostics). For analysis of tumor-TIL conjugates, cells were mixed at a 1:1 ratio in RPMI (without serum) at 4°C and induced to form conjugates (pulse spun at 16,000 × g), solubilized, immunoprecipitated, and immunoblotted as described (9). Densitometric analysis of selected bands was performed using different exposures of the X-ray films.

Results

An assay was established to test if tumor cell isolation affected the phenotype of either TIL or tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. S1). MCA38 primary tumor cells were isolated by collagenase digestion and plated in vitro. After overnight incubation, CD8+ TIL were isolated (“p-TIL”, for “plated TIL”) and assayed for lytic function in comparison to freshly isolated TIL (“nonlytic TIL”) and also TIL that were purified and cultured briefly (“lytic TIL”), a treatment that allows the recovery of lytic function (9, 12). Similar to freshly isolated nonlytic TIL, TIL recovered following overnight culture in vitro (p-TIL) are nonlytic (Fig. 1A), thus inhibition of TIL function by primary tumor cells is not abrogated by enzymatic digestion nor overcome by in vitro culture. p-TIL can recover lytic function if purified and briefly cultured in the absence of tumor (“p-TIL recovered”), similar to TIL that are purified and briefly cultured (lytic TIL). Furthermore, TCR signaling defects that characterize freshly isolated nonlytic TIL are maintained in p-TIL during in vitro culture (Supplementary Fig. S2). These data support the notion that a cell in the primary tumor is responsible for the inhibition of TIL lytic function.

Figure 1.

Primary MCA38 tumor cells or MCA38 cell line inhibits TIL lytic function. A, nonlytic TIL recover lytic activity after purification and brief culture in vitro. Freshly-isolated TIL (Nonlytic TIL) were prepared and tested for lytic function using the cognate cell line as targets as previously described (22). A portion of nonlytic TIL was cultured for ~6 h in vitro before cytolysis assay (Lytic TIL). Separately, but from the same tumor (as described diagrammatically in Supplementary Fig. S1), primary tumor cells were plated overnight at 200 × 106 cells/15 cm dish in complete medium. After incubation, cells were harvested and CD8+ TIL isolated by immunomagnetic beading. TIL recovered from the total primary tumor were immediately tested for lytic function against cognate MCA38 target cells (p-TIL) or following in vitro culture (p-TIL recovered). B, nonlytic TIL recover lytic activity after culture with primary tumor cells in separation (Transwell) chambers. Primary tumor cells were prepared, plated (2 × 106 cells/well in 12-well dishes), and incubated at 37°C for 3 h before nonlytic TIL were added to the Transwell inserts. Freshly isolated TIL were prepared and plated at 106 cells/Transwell insert. Cells were incubated overnight, after which TIL were reisolated from the Transwell inserts before cytolysis assay using cognate MCA38 cells as targets. C, nonlytic TIL recover cytolysis after culture in conditioned medium from primary tumor cells and MCA38 cells. Primary MCA38 tumor cells were prepared and plated (200 × 106 cells/15 cm dish), and 107 of the MCA38 cell line was plated in a T175 flask for 24 h in 40 mL of medium. Conditioned medium was collected and nonlytic TIL were cultured in this conditioned medium for 20 h (2 × 106 cells/24-well; 2 mL) or in RPMI 1640 (Lytic TIL) before cytolysis assay. D, lytic TIL retain function after culture with MCA38 cells in separation chambers. CD8+ TIL were prepared and plated (2 × 106 cells/well in 24-well tissue culture dishes) overnight. TIL were then plated (106 cells/Transwell insert) in 12-well tissue culture dishes [±2 × 106 MCA38 cells previously plated overnight in the bottom well, Lytic TIL + cell line (Transwell, bottom)], in coculture with tumor cells (Lytic TIL + cell line), or in Transwell inserts with a mixture of lytic TIL plus cognate tumor cell line in the bottom well. After 6 h of incubation, TIL were reisolated from the Transwell inserts and analyzed for lytic activity [Lytic TIL + cell line in contact with lytic TIL (Transwell, bottom)]. Points, mean of triplicate wells for each E/T ratio; bars, SE. This experiment was repeated six times with equivalent results.

To determine if tumor-induced defective cytolysis is mediated by a soluble or contact-dependent factor, we used cell separation chambers in coculture experiments (described in Supplementary Fig. S3). Nonlytic TIL cultured above primary tumor cells recover lytic function (Fig. 1B), thus primary tumor cells, shown to inhibit the recovery of lytic function if cultured in contact with TIL (Fig. 1A), do not secrete a soluble inhibitory factor. To confirm this finding, nonlytic TIL were cultured in conditioned medium collected from total primary tumor cells or the cognate tumor cell line before assay (Fig. 1C). Conditioned medium does not contain a constitutively secreted inhibitory factor. Similar to nonlytic TIL, lytic TIL are not inhibited by exposure to shared medium of the MCA38 cell line (Fig. 1D, or total primary tumor cells; data not shown). However, lytic TIL cultured in contact with primary tumor or the cognate cell line lose lytic function (Figs. 1D and 2A). Lytic TIL cocultured with syngeneic MC57G fibrosarcoma (or B-16 or MB49 cells; data not shown) maintain lytic function (Fig. 2A) inferring that, because MC57G TIL are also transiently suppressed in lytic function (12), antigen recognition is required to induce suppression.

Figure 2.

Characterization of tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived cells. A, MC57G tumor cells do not suppress TIL lytic activity. Nonlytic TIL were isolated from MCA38 tumors and allowed to recover lytic function in vitro as described previously in contact with either cognate MCA38 cells or syngeneic MC57G cells (2 × 106 MC57G or MCA38 cells as indicated plus 106 lytic anti-MCA38 TIL in 12-well plates for 6 h). After coculture, TIL were reisolated by magnetic immunobeading (without additional magnetic immunobeads) and analyzed for lytic activity against cognate MCA38 target cells. Points, mean of triplicate wells for each E/T ratio; bars, SE. B, iNOS expression is induced by IFN-γ in MDSC isolated from primary MCA38 tumors. Primary MCA38 tumor cells were depleted of CD11b+ MDSC by two rounds of magnetic immunobeading as described (16) and purified MDSC collected as indicated. Cells (2 × 106) were cultured for 6 h with either no additions or supplemented with IFN-γ or IL-4 (both at 100 ng/mL) before the equivalent of 0.25 × 106 cells per gel lane were detergent-lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting for iNOS and actin. Aliquots of tumor cells used for the immunoblot analysis, before and after depletion of MDSC, were analyzed by flow cytometry using FITC-conjugated anti-F4/80 and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD11b (bottom). The percentage of labeled cells in each quadrant is shown. C, nitrite determination of cultured MCA38 primary tumor cells. Primary tumor cells (total tumor cells, tumor cells after magnetic immunobead depletion of MDSC, or purified MDSC as indicated) were plated in the presence or absence of IFN-γ or IL-4 as described above. Supernatants were collected after 6 h and analyzed for nitrite concentration. D, arginase assay of primary MCA38 tumor cells or MCA38 cell line. Arginase activity in primary MCA38 tumor cells was determined by plating 2 × 106 cells/12-well dishes in the presence or absence of IFN-γ or IL-4 (both at 100 ng/mL). After 6 h, cells were harvested, washed with HBSS, and then assayed for urea production. Cell lysates equivalent to 25 × 103 primary tumor cells were used for individual arginase determinations. Columns, mean of triplicate wells for different combinations of cells; bars, SE (C and D). Each component of this figure was repeated more than six times with equivalent results.

Robust literature suggests that altered L-arginine metabolism in the tumor environment (20) or secondary lymph organs (21) are inhibitory for immune cell function, therefore, we asked if TIL lytic dysfunction is mediated by iNOS and/or arginase. Primary tumor cells, tumor cells depleted of MDSC, or purified MDSC were tested for the expression of iNOS after culture in the presence or absence of IL-4 (which induces arginase) or IFN-γ (which induces iNOS; Fig. 2B). Total primary tumor cells and purified MDSC express iNOS that is inducible by IFN-γ. Culture supernatants from primary tumor cells or MDSC were assayed for nitrite production, which showed that iNOS was active in MDSC even without IFN-γ treatment (Fig. 2C). Similarly, primary tumor cells were assayed for arginase and showed strong arginase activity in MDSC (Fig. 2D; arginase activity in MDSC is particularly robust, ~20 × 10−5 μg urea/cell/6 h, increasing to 38 × 10−5 μg urea/cell/24 h, as opposed to <0.5 × 10−5 μg urea/cell/24 h in MCA38 cells).

To test the role of MDSC in the induction of TIL lytic dysfunction, coculture of nonlytic or lytic TIL in contact with either purified MDSC or primary tumor cells depleted of MDSC was performed (Fig. 3A and B, respectively). Surprisingly, in spite of the evident iNOS and arginase activities expressed by MDSC, non-lytic TIL cultured with MDSC recover lytic function; similarly, lytic TIL are not induced to the nonlytic phenotype. However, primary tumor cells effectively depleted of MDSC (Fig. 2B) both prevent the recovery of lytic function in freshly isolated nonlytic TIL and induce lytic dysfunction in lytic TIL.

Figure 3.

MCA38 tumor cells rapidly induce cytolytic dysfunction in TIL. A and B, MCA38 tumor cells suppress TIL lytic activity. Primary tumor cells (2 × 106) after magnetic immunobead depletion of MDSC or purified MDSC were cocultured (in 12-well plates with 4 mL of medium) with 106 nonlytic TIL or 106 lytic TIL (B) for 12 and 6 h, respectively. After coculture, TIL were reisolated by one round of magnetic immunobeading (without additional magnetic immunobeads) and analyzed for lytic activity. C, MCA38 cells rapidly suppress TIL lytic activity after contact in vitro. MCA38 tumor cells (2 × 106) were cocultured with nonlytic TIL (106) for the indicated times (1–15 h) after which they were reisolated by magnetic immunobeading and analyzed for lytic activity. Points, mean of triplicate wells for each E/T ratio; bars, SE. This experiment was performed thrice with equivalent results.

These data show that it is tumor cells, not tumor MDSC (or regulatory T cells), which suppress TIL lytic activity in a contact-dependent manner. To further understand this phenotype, a kinetic analysis was performed in which the tumor cell line was cultured with lytic TIL for different times before cytolytic assay (Fig. 3C). Complete inhibition of TIL lytic function was seen after 3 h of coculture, and substantial (but partial) inhibition was observed after 1 h, suggesting that tumor-induced TIL suppression is achieved very rapidly.

Based on the observation that both CD3ζ (Supplementary Fig. S4) and ZAP-70 (9) localizes to the tumor contact site in nonlytic TIL/tumor cell conjugates, we analyzed the phosphorylation status of CD3ζ by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies to test the authenticity of the in vitro TIL stimulation protocol. At early times of TIL/tumor conjugation, nonlytic TIL and lytic TIL phosphorylate CD3ζ equivalently, proving that contact with cognate tumor cells trigger TIL in vitro (Fig. 4A). However, at later times of conjugation, CD3ζ phosphorylation in nonlytic TIL is diminished compared with lytic TIL conjugated at equivalent times. We similarly analyzed the phosphorylation status of the activation p56lck motif (Y394) as a function of conjugation in vitro by immunoprecipitation of p56lck from TIL/tumor conjugates and reciprocal blotting. p56lck pY394 in nonlytic TIL is initially phosphorylated upon binding to cognate tumor cells (Fig. 4B, compare “TIL only” to time “10 s”) but is rapidly dephosphorylated (ca. <30 s) both suggesting that CD45 is functioning appropriately but that Y394 is dephosphorylated with increasing times of conjugation. By stripping the blots and reprobing with antibody reactive with the phosphorylated form of the p56lck inhibitory motif (pY505), we similarly determined the phosphorylation status of the inhibitory motif as a function of conjugation in vitro. We found that Y505 is not phosphorylated in nonlytic TIL upon conjugation (Fig. 4B), supporting the notion that p56lck is not regulated by Csk-mediated phosphorylation of the Y505 inhibitory motif, even though Csk localizes to the TIL/tumor cell contact site (Supplementary Fig. S5). The inhibitory Y505 motif becomes phosphorylated at later times of conjugation in vitro (ca. >8 min).

Figure 4.

p56lck in nonlytic TIL is rapidly dephosphorylated upon conjugation with cognate tumor cells. A, phosphorylation status of CD3ζ. Nonlytic or lytic TILs (106) were mixed with 106 MCA38 cells, pulse-centrifuged, and incubated at 37°C for the indicated times. Cell pellets were lysed and immunoprecipitated with 0.002 mg of anti-CD3ζ per sample before immunoblotting with either anti-CD3ζ or antiphosphotyrosine. B, analysis of p56lck pY505 and pY394 levels. Nonlytic or lytic TILs (106) were mixed with 106 MCA38 cells, pulse-centrifuged, and incubated at 37°C for the indicated times before detergent extraction and analysis by immunoblotting as described (9). TIL/tumor conjugate extracts were immunoprecipitated with 0.002 mg of anti-p56lck per sample (clone 3A5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and immunoblotted sequentially with 0.0002 mg/mL of p56lck pY394, 0.000175 mg/mL of p56lck pY505 (Cell Signaling), or 0.0002 mg/mL of total p56lck (clone 2102, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The films were scanned using Adobe Photoshop and densitometry was performed using Kodak 1D3.5.4USB software. For analysis of p56lck, in each case, the signal for the “TIL only” samples was set to “1.0” and the signals for different times of conjugation were compared and shown as that ratio under each gel lane. This experiment was repeated (using the same and several different times of conjugation) five times with equivalent results.

In contrast, lytic TIL phosphorylate p56lck Y394 upon conjugation with tumor cells in vitro, which is maintained at increased times of conjugation when this nonlytic TIL motif is dephosphorylated (Fig. 4B, bottom). In lytic TIL, the p56lck inhibitory motif (Y505) remains in the nonphosphorylated state until later times of conjugation (>8 min). Collectively, these data highlight that p56lck is being regulated in nonlytic TIL by dephosphorylation of the activation motif (Y394) and not by increased (or maintained) phosphorylation of its inhibitory motif (Y505).

Because the p56lck activation motif is a major target of Shp-1 (22), we asked if Shp-1 displayed a localization phenotype in TIL. Confocal microscopy of lytic TIL showed that Shp-1 dispersed throughout the cell but was localized at the tumor contact site in conjugates formed with nonlytic TIL (Fig. 5A), supporting the notion that Shp-1 is in physical proximity with p56lck in nonlytic TIL. Because Erk has been suggested to be a positive regulator of T cell signaling (23), we also stained TIL/tumor conjugates and showed that activated Erk was excluded from the tumor contact site in nonlytic TIL conjugates (in which p56lck is localized; Supplementary Fig. S4), a pattern that is reversed in lytic TIL. That observation supports the notion that in conjugates of nonlytic TIL, Erk cannot provide positive feedback regulation of Shp-1 inhibition (24).

Shp-1 activity is reflected by its tyrosine phosphorylation status (17); therefore, to infer Shp-1 activity, we analyzed Shp-1 phosphorylation by reciprocal immunoblotting. Shp-1 was immunoprecipitated from nonlytic or lytic TIL and blotted with anti-phosphotyrosine (Fig. 5B), which showed that Shp-1 is robustly tyrosine-phosphorylated in nonlytic TIL compared with lytic TIL (~3- to 4-fold more). In vitro phosphatase assays showed that Shp-1 immunoprecipitated from nonlytic TIL is ~3.8-fold more active than from lytic TIL, corroborating the phosphotyrosine blotting (Fig. 5C) and directly demonstrating elevated Shp-1 activity in nonlytic TIL (assay of Shp-1 isolated from MCA38 cells, which may potentially contaminate TIL preparations, showed that Shp-1 activity in likely numbers of MCA38 cells in TIL preparations is negligible).

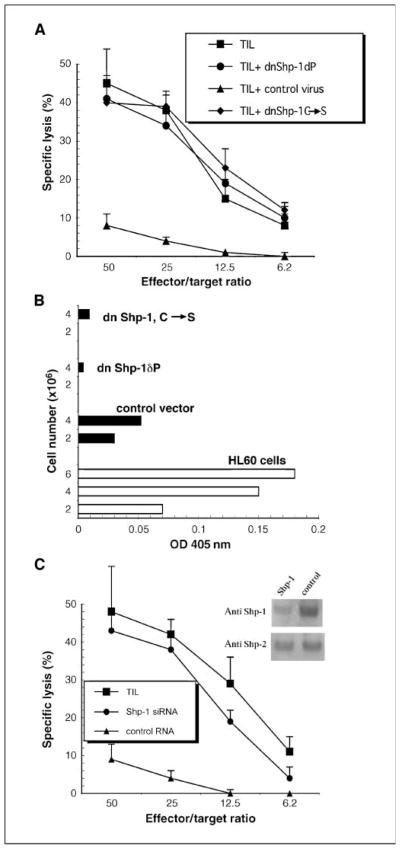

An additional experimental approach showed the essential role of Shp-1 in defective TIL signaling. We asked if targeted inhibition of Shp-1 in lytic TIL would block in vitro tumor-induced lytic dysfunction by expression of dominant-negative Shp-1 alleles before the reversion assay. TIL were isolated, cultured briefly, transduced with virus expressing one of two different dnShp-1 constructs (a mutant in which the kinase domain is deleted or a point mutant in which the active site Cys is changed to Ser; ref. 17) or a control virus lacking dnShp-1. After recovery, TIL were briefly cultured in contact with cognate tumor (reversion) and then assayed for lytic function. Lytic TIL transduced with retrovirus expressing dnShp-1 before coculture with cognate MCA38 cells retain lytic function (Fig. 6A). However, TIL infected with the control virus do not resist tumor-induced induction of defective cytolysis and are efficiently rendered nonlytic. Those observations show that functional Shp-1 in TIL is required in order to be susceptible to reversion to the nonlytic phenotype. In vitro assay of Shp-1 activity in transduced TIL is consistent with in vitro Shp-1 phosphatase activity (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Lytic TIL expressing dominant-negative Shp-1 resist tumor-induced reversion of the lytic phenotype. A, TIL were isolated from MCA38 tumors, cultured in vitro for 6 h, and then cocultured overnight with retrovirus-producer cell lines expressing either dnShp-1 or control virus. TIL were then collected by passage over magnetic columns, cultured with MCA38 cells for 3 h (2 × 106 TIL/well, 24-well plate containing 2 × 105 adherent MCA38 cells/well), repurified, and tested for cytolysis using MCA38 cells as targets. B, in vitro phosphatase assays were done on lytic TIL that were transduced with virus expressing dnShp-1 alleles or the control virus (as in A above) exactly as described in the legend to Fig. 5C. Either 2 or 4 × 106 TIL were analyzed as indicated and HL60 cells were used as positive controls for Shp-1 immunoprecipitation and the phosphatase assay. C, TIL were isolated from MCA38 tumors, cultured in vitro for 6 h, and then transfected with Shp-1 or control siRNA as described in Materials and Methods. Forty-eight hours later, TIL were collected by centrifugation and used in reversion assays followed by cytolysis as described in A. Total TIL cell extracts immunoblotted for Shp-1 followed by Shp-2 as indicated (inset).

In additional corroborative experiments, TIL were transfected with siRNA (targeting a Shp-1 sequence shown by others to inhibit Shp-1 activity; refs. 18, 19) before use in reversion assays (Fig. 6C). After transfection, Shp-1 levels were assessed by immunoblotting (Fig. 6C) and Shp-1 levels were <20% of TIL which were transfected with a control RNA. The specificity of siRNA targeting was shown by blotting TIL extracts for expression levels of a related phosphatase, Shp-2, whose levels were unaffected by transfection of Shp-1 siRNA. Similar to TIL in which dnShp-1 alleles were expressed before short-term coculture with cognate MCA38 cells (Fig. 6A), TIL receiving Shp-1 siRNA did not revert to the nonlytic phenotype (Fig. 6C). Thus, two different experimental approaches that inhibit either the function or the levels of expression of Shp-1 show that TIL require Shp-1 in order to be susceptible to the tumor-induced, contact-dependent induction of lytic dysfunction.

Discussion

Confocal microscopic, biochemical, and fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis previously showed that nonlytic TIL in our tumor model are triggered by conjugate formation in that the TCR, p56lck, CD3ζ, LFA-1, lipid rafts, ZAP-70, and LAT localize at the TIL/tumor cell contact site, and that CD43 and CD45 are excluded. However, proximal TCR signaling is blocked in that activation of ZAP-70 (pY493) is only modest (9). This level of activated ZAP-70 is unable to propagate the activation signal, as total cell phosphotyrosine is not increased and cells do not elevate calcium levels. Because nonlytic TIL and lytic TIL contain similar levels of p56lck and CD3ζ proteins which localize to the contact site in tumor cell conjugates (Supplementary Fig. S4), weak ZAP-70 activation in nonlytic TIL is not due to deficient levels or exclusion of CD3ζ or p56lck from the signaling complex. In our current experiments, we analyzed the kinetics of activation of p56lck upon in vitro conjugation with cognate tumor cells. Freshly isolated nonlytic TIL are triggered by conjugation in that CD3ζ is phosphorylated coincident with phosphorylation of the activation motif of p56lck, Y394. CD3ζ remains phosphorylated for times at which p56lck Y394 is dephosphorylated (ca. >10 s), suggesting that CD3ζ is not a substrate for the phosphatase that dephosphorylates p56lck.

When TIL are purified and briefly cultured in vitro in the absence of tumor, lytic function is restored. In biochemical terms, activation of p56lck is significantly sustained compared with nonlytic TIL. Thus, inactivation of p56lck (dephosphorylation of Y394) in nonlytic TIL is rapid, but in lytic TIL, this inactivation is much slower. The activation status of p56lck in the two TIL populations reflects the lytic activity of these respective populations. Based on the rapid kinetics of induction of defective T cell signaling observed when lytic TIL are cultured in vitro with tumor cells, the mechanism of signaling blockade involves a fast-acting initiator. Delivered in a contact-dependent manner by the tumor cell to the TIL, this trigger acts as a dominant switch that is able to override the positive signal generated by antigen recognition. This may explain the lytic defect in TIL which are CD69+ and thus have recently interacted with antigen (11).

Our data show that defective TIL signaling is likely mediated by Shp-1 in that Shp-1 activity is enhanced in nonlytic TIL, inhibition of p56lck activity and lytic function is rapidly induced upon tumor contact, and inhibition of Shp-1 activity in lytic TIL prevents tumor-induced TIL lytic dysfunction (Fig. S6). Other potential targets of Shp-1 may also be inactivated in nonlytic TIL (e.g., ZAP70 or Vav-1) but being positioned at the top of the TCR signaling cascade, p56lck inactivation efficiently inhibits all TIL effector functions, therein preventing T cell elimination of tumor. Activation of Shp-1 in TIL by tumor contact is interpreted to mean that MDSC do not inhibit the effector phase of CD8+ antitumor T cells in spite of robust metabolic activity in tumor MDSC. It is possible that our in vitro analysis of the consequences of TIL interaction with MDSC do not faithfully represent MDSC function in situ in that TIL have been manipulated by isolation and brief culture in vitro. However, the observation that re-exposure of lytic TIL to tumor cells in vitro induces the same functional and biochemical phenotypes of freshly isolated nonlytic TIL argues that purified TIL maintain responsiveness to inhibitory environmental cues, and that MDSC do not provide that signal.

Several essential aspects of this novel tumor escape mechanism from antitumor T cell killing remain unresolved: rapid induction of Shp-1 activity is likely to depend on TIL recognition of a tumor cell surface ligand, which by analogy to Shp-1 activation and function in B cell signaling (25), results in the tyrosine phosphorylation of a TIL-inhibitory receptor protein that in turn causes recruitment of Shp-1 into proximity with its target p56lck (Supplementary Fig. S6). The identity of the TIL-inhibitory receptor, and its tumor counter-ligand, are currently unknown.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: NIH CA108573 from the NIH.

For generous provision of reagents we thank: D. Wiest (Basic Science Division, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA) for anti-CD3ζ, U. Lornez (Department of Microbiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA) for dnShp-1 alleles, J. Zhao (Department of Pathology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK) for siRNA plasmids, and the M. Philips (Department of Cell Biology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY) and R. Dasgupta (Department of Pharmacology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY) labs for control siRNAs. We thank Miranda Kim for help in the arginase assays.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Schreiber H, Wu TH, Nachman J, et al. Immunodominance and tumor escape. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:25–31. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Disis ML, Calenoff E, McLaughlin G, et al. Existent T-cell and antibody immunity to HER-2/neu protein in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pittet MJ, Speiser DE, Valmori D, et al. Ex vivo analysis of tumor antigen specific CD8+ T cell responses using MHC/peptide tetramers in cancer patients. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1235–47. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiteside TL, Parmiani G. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes: their phenotype, functions and clinical use. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1994;39:15–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01517175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahin U, Tureci O, Pfreundschuh M. Serological identification of human tumor antigens. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:709–16. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prevost-Blondel A, Zimmermann C, Stemmer C, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes exhibiting high ex vivo cytolytic activity fail to prevent murine melanoma tumor growth in vivo. J Immunol. 1998;161:2187–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–15. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frey AB, Monu N. Effector-phase tolerance: another mechanism of how cancer escapes antitumor immune response. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:652–62. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koneru M, Schaer D, Monu N, et al. Defective proximal TCR signaling inhibits CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte lytic function. J Immunol. 2005;174:1830–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radoja S, Rao TD, Hillman D, et al. Mice bearing late-stage tumors have normal functional systemic T cell responses in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;164:2619–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radoja S, Saio M, Frey AB. CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are primed for Fas-mediated activation-induced cell death but are not apoptotic in situ. J Immunol. 2001;166:6074–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radoja S, Saio M, Schaer D, et al. CD8(+) tumor-infiltrating T cells are deficient in perforin-mediated cytolytic activity due to defective microtubule-organizing center mobilization and lytic granule exocytosis. J Immunol. 2001;167:5042–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koneru M, Monu N, Schaer D, et al. Defective adhesion in tumor infiltrating CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:6103–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saio M, Radoja S, Marino M, et al. Tumor-infiltrating macrophages induce apoptosis in activated CD8(+) T cells by a mechanism requiring cell contact and mediated by both the cell-associated form of TNF and nitric oxide. J Immunol. 2001;167:5583–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misko TP, Schilling RJ, Salvemini D, et al. A fluorometric assay for the measurement of nitrite in biological samples. Anal Biochem. 1993;214:11–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schimke RT. The importance of both synthesis and degradation in the control of arginase levels in rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:3808–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilgore NE, Carter JD, Lorenz U, et al. Cutting edge: dependence of TCR antagonism on Src homology 2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase activity. J Immunol. 2003;170:4891–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.4891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen D, Iijima H, Nagaishi T, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellular adhesion molecule 1 isoforms alternatively inhibit and costimulate human T cell function. J Immunol. 2004;172:3535–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang N, Li Z, Ding R, et al. Antagonism or synergism. Role of tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 in growth factor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21878–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605018200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bronte V, Serafini P, Mazzoni A, et al. L-Arginine metabolism in myeloid cells controls T-lymphocyte functions. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:302–6. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabrilovich D. Mechanisms and functional significance of tumour-induced dendritic-cell defects. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:941–52. doi: 10.1038/nri1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiang GG, Sefton BM. Specific dephosphorylation of the Lck tyrosine protein kinase at Tyr-394 by the SHP-1 protein-tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23173–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watts JD, Sanghera JS, Pelech SL, et al. Phosphorylation of serine 59 of p56lck in activated T cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23275–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkler DG, Park I, Kim T, et al. Phosphorylation of Ser-42 and Ser-59 in the N-terminal region of the tyrosine kinase p56lck. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5176–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nitschke L. The role of CD22 and other inhibitory co-receptors in B-cell activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.