Abstract

Background

Cryptorchidism (undescended testis) is the most common genitourinary anomaly in male infants.

Methods

We reviewed the available literature on the diagnostic performance of ultrasound, CT, and MRI in localizing undescended testes.

Results

Ultrasound is the most heavily utilized imaging modality to evaluate undescended testes. Ultrasound has variable ability to detect palpable testes and has an estimated sensitivity and specificity of 45% and 78%, respectively, to accurately localize non-palpable testes. Given the poor ability to localize non-palpable testes, ultrasound has no role in the routine evaluation of boys with cryptorchidism. MRI has greater sensitivity and specificity, but is expensive, not universally available, and often requires sedation for effective studies of pediatric patients. Diagnostic laparoscopy has nearly 100% sensitivity and specificity for localizing non-palpable testes and allows for concurrent surgical correction.

Conclusions

While diagnostic imaging does not have a role in the routine evaluation of boys with cryptorchidism, there are clinical scenarios in which imaging is necessary. Children with ambiguous genitalia or hypospadias and undescended testes should have ultrasound evaluation to detect the presence of Mullerian structures. Future studies should examine whether pre-operative MRI has utility in re-operative orchiopexy.

Keywords: cryptorchidism; ultrasound, diagnostic performance; diagnostic imaging

Background

Cryptorchidism is the most common genitourinary anomaly in male infants. Cryptorchidism occurs in 1–3% of full-term and up to 30% of premature male infants.[1, 2] Boys with cryptorchidism are at increased for risk for infertility and testicular cancer. [3–5] Studies have shown that fertility parameters decrease the longer a testis remains undescended and that the risk of testis cancer can be decreased if orchiopexy is performed before puberty.[5] In order to possibly halt or reverse germ cell loss and decrease cancer risk, orchiopexy is recommended at 12 months of age. [6, 7] Initial diagnosis and referral of boys with undescended testes is made by primary care providers who diagnose cryptorchidism during routine physical examination.

An undescended testis may be found adjacent to the kidneys in the retroperitoneum to any point along the path of testicular descent into the dependent hemiscrotum. The testis may also be ectopic and found in areas such as the superficial pouch of Denis-Browne, along the penile shaft or on the contralateral side. Physical examination is the cornerstone of the diagnosis of cryptorchidism and determination of the position of the undescended testis. Careful examination of the scrotum including a contralateral descended testis, pre-inguinal space, pubic tubercle, and the inguinal canal in the clinic will usually demonstrate an undescended testis at or distal to the internal inguinal ring. In one series, over 70% of undescended testes are palpable.[8] That leaves approximately 30% of testes that cannot be localized by physical exam. A non-palpable testis may be \ intra-abdominal, absent, or ectopic or simply not appreciated on physical exam in the clinic in children that are uncooperative, obese, or have undergone previous surgery that has obscured inguinal-scrotal anatomy. Diagnostic imaging has been utilized to determine the anatomic location of non-palpable testes. Accurate pre-surgical localization of the testis could spare a child an operation in the setting of an absent testis or limit the extent of surgery if the testis can be definitively identified. However, the potential benefits of imaging must be weighed against its risks, costs, and whether it provides information critical to the care of the child with cryptorchidism.

Current US Department of Health and Human Services guidelines state that ultrasound, CT, or MRI do not provide additional information to the physical examination.[9] Given the increased emphasis on comparative effectiveness in medical practice, we believe it is necessary to understand the reasons to image and not image a child with cryptorchidism. We review the utility of ultrasound, CT, and MRI in the evaluation of boys with undescended testes and also address clinical scenarios in which the presence of associated abnormalities merits the use of diagnostic imaging.

Surgical approach

With the possible exception of undetectable serum testosterone after HCG stimulation in a boy with bilateral non-palpable testes, all boys with cryptorchidism require surgery to bring a viable testis down to scrotum, remove non-viable testicular tissue identified in the exploration, or to confirm that a testis is absent.[10] The operative approach for cryptorchidism is based upon the palpability of the testis at the time of exam under anesthesia.

When the testis is palpable, an inguinal or prescrotal orchiopexy is performed. If the testis remains non-palpable under anesthesia, laparoscopy is the preferred diagnostic and therapeutic approach, although open surgery is still a viable option. Initial diagnostic laparoscopy or inguinal exploration will identify a viable testis or confirm an absent testis by revealing blind-ending spermatic vessels or a non-viable nubbin.[11–15] With only rare reports of an inguinal testis misidentified during surgical exploration, laparoscopy has nearly 100% sensitivity and specificity to localize a testis or confirm its absence.[16–18] Indeed, diagnostic laparoscopy has become the gold standard against which diagnostic imaging studies are measured.[19–21] However, if diagnostic imaging could reliably determine the presence and location of a non-palpable testis, a child could be spared an operation (in the setting of an absent testis) or could undergo a more limited operation restricted to where the testis was seen on pre-operative imaging evaluation.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is non-invasive and does not emit ionizing radiation. It is heavily utilized in the evaluation of boys with cryptorchidism. In an on-line survey of a national sample of general pediatricians practicing in the United States, Tasian et al. reported 67% of respondents order imaging during the pre-surgical evaluation of boys with cryptorchidism, with 34% always or usually doing so. Of those who reported ordering imaging, 96% reported utilizing ultrasound.[22] While this study was limited by the weaknesses inherent to survey research such as recall and response bias, it is apparent that ultrasound is the most heavily utilized imaging modality in the evaluation of boys with cryptorchidism.

From the first reports of ultrasound evaluation of the undescended testicle in the 1970s, numerous subsequent studies have been conducted that have examined the utility of ultrasound in cryptorchidism.[23] Identification of the mediastinum testis, which appears as an echogenic band, is considered necessary to accurately identify a testis.[24] However, Weiss et al. reported a 10% false positive rate in ultrasound evaluation of undescended testes, with both instances due to incorrectly identifying the gubernaculum as the testis. Over the last twenty years, ultrasound technology has advanced with newer transducers having greater resolution and presumably greater ability to differentiate a gonad from surrounding structures. Using 5MHz and 7.5MHz transducers, Kullendorff et al. reported in 1985 correctly localizing 87% of palpable testes, which is higher than the 70% reported by Weiss in 1986.[25, 26] Twenty years later in 2007, using 5–12MHz and 7–10MHz transducers, Nijs reported that ultrasound failed to identify all 14 of viable intraabdominal testes. Thus, despite the advances in ultrasound technology, ultrasound cannot reliably identify intra-abdominal testes, which comprise 20% of all undescended testes.[8]

For palpable testes, there are widely discordant reports of the concordance between physical exam and ultrasound findings. Kullendorff et. al. reported that ultrasound demonstrated accordance with the physical exam 93% of the time. However, in 2002, Elder reported that of the 45 testes palpable either in the scrotum or in the inguinal canal on physical exam by a pediatric urologist only 12 were identified by ultrasound.[27] Therefore, for palpable testes, it appears that ultrasound, at best, adds little to the physical exam and, at worst, provides misleading information.

However, 80% pediatricians indicate that a non-palpable testis is the factor that most influences them to order an ultrasound and 86% reported the belief that ultrasound reliably identifies a non-palpable testis.[22] The question then becomes, in the setting of a non-palpable testis, how effective is ultrasound in accurately localizing a testis or confirming its absence? Kullendorff reported that ultrasound correctly located 33% of non-palpable testes.[25] Of the four non-palpable testes identified by ultrasound, one was at the internal ring, 2 in the inguinal canal and one at the external ring. No intraabdominal testes were identified.[25] Elder also reported on the cohort of patients who had non-palpable testes all of whom had negative ultrasounds. All of these boys were found to have either viable intra-abdominal testes or atrophic nubbins upon surgical exploration.[27] From these studies, we can draw the conclusion that ultrasound can potentially identify non-palpable testes in the inguinal canal but not within the abdomen.

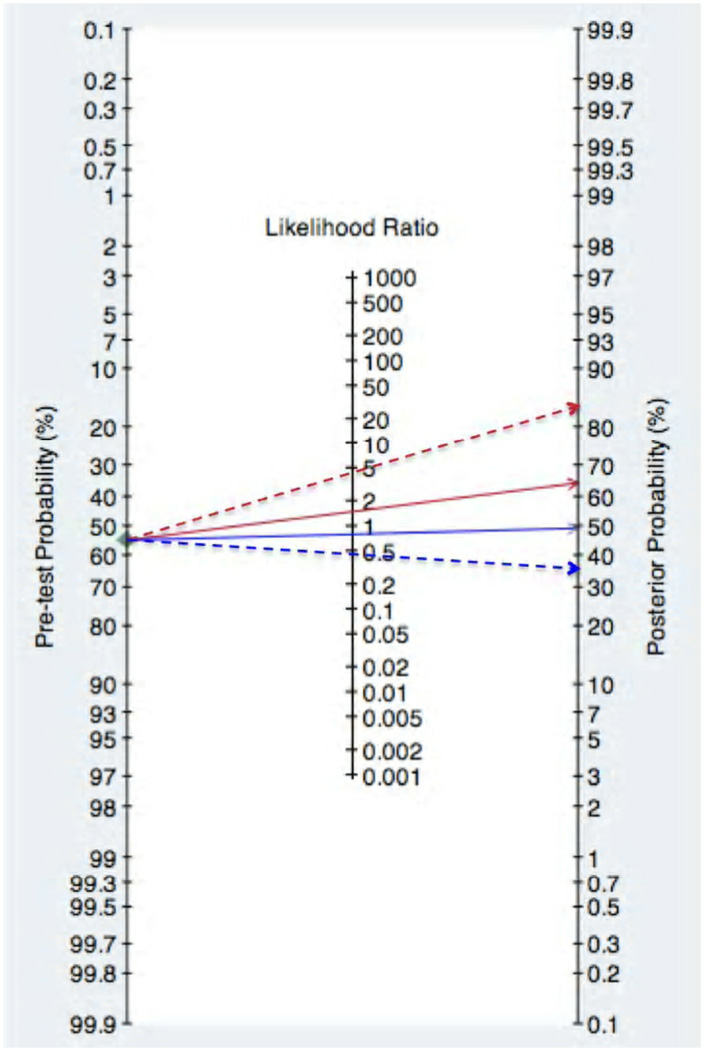

Tasian and Copp recently performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of literature on ultrasound evaluation of non-palpable undescended testes. They found that the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in correctly identifying a non-palpable testis was 45% and 78%, respectively. The positive and negative predictive values, which are the increase and decrease in the odds of a testis actually being in the position identified by ultrasound were 1.48 and 0.79, respectively.[28] Previously published studies on the anatomic location of consecutive subjects with non-palpable testes in whom testis location was prospectively recorded at the time of surgery demonstrated that the likelihood that a non-palpable testis is intra-abdominal is 55%. The remainders are located in the inguinal scrotal region (30%) or are absent (15%).[8, 29, 30] Using the positive and negative predictive values, a positive ultrasound increases and negative ultrasound changes the probability that a non-palpable testis is located within the abdomen from 55% to 64% and 49%, respectively. Using the upper and lower confidence limits of the positive and negative predictive values, which assumes the best possible performance of ultrasound, the probability that a non-palpable testis is located within the abdomen is 83% and 36% if the testis is seen or not seen on ultrasound, respectively (Figure 1). From this, the authors conclude that that pre-operative ultrasound does not reliably localize non-palpable testes and is not useful in determining the surgical management of these patients.[28]

Figure 1. Effect of Ultrasound on the Probability of Testis Location.

The pre-test probability that a non-palpable testis is within the abdomen is 55%. Using the positive likelihood ratio point estimate (solid red line) and upper confidence limit (dashed red line), an ultrasound that localizes a non-palpable testis within the abdomen increases the probability that the testis is truly in the abdomen to 64% and 83%, respectively. Using the negative likelihood ratio point estimate (solid blue line) and lower confidence limit (dashed blue line), an ultrasound that does not visualize a non-palpable testis decreases the probability that the testis is truly in the abdomen to 49% and 36%, respectively. (originally published in Pediatrics 127:119–128, 2011; permission for reproduction obtained from Pediatrics)

Reliance on ultrasound to detect or rule out intra-abdominal testes confers potential significant consequences. Because there is still a significant likelihood (up to 49%) that a testis is intra-abdominal even if it is not seen by ultrasound choosing not to operate in this setting potentially increases the risk that a testis is left in the abdomen and subsequently develops testicular carcinoma. Additionally, given the intra-abdominal location of the testis, the child would be at higher risk for presentation with advanced disease due to the inability to perform routine screening physical exams.[5, 31]

CT

In the early 1980s, Lee et al. reported that CT correctly localized 100% of 8 undescended testes; however, 5 of these were potentially palpable in the inguinal canal. [32, 33] Recent studies have demonstrated the risk of secondary malignancies conferred by ionizing radiation, which is especially pronounced in the pediatric population.[34] While CT has an important role in the staging of testis cancer for which boys with history of cryptorchidism are at risk, we believe there is no role for routine CT evaluation of boys with undescended testes.

MRI

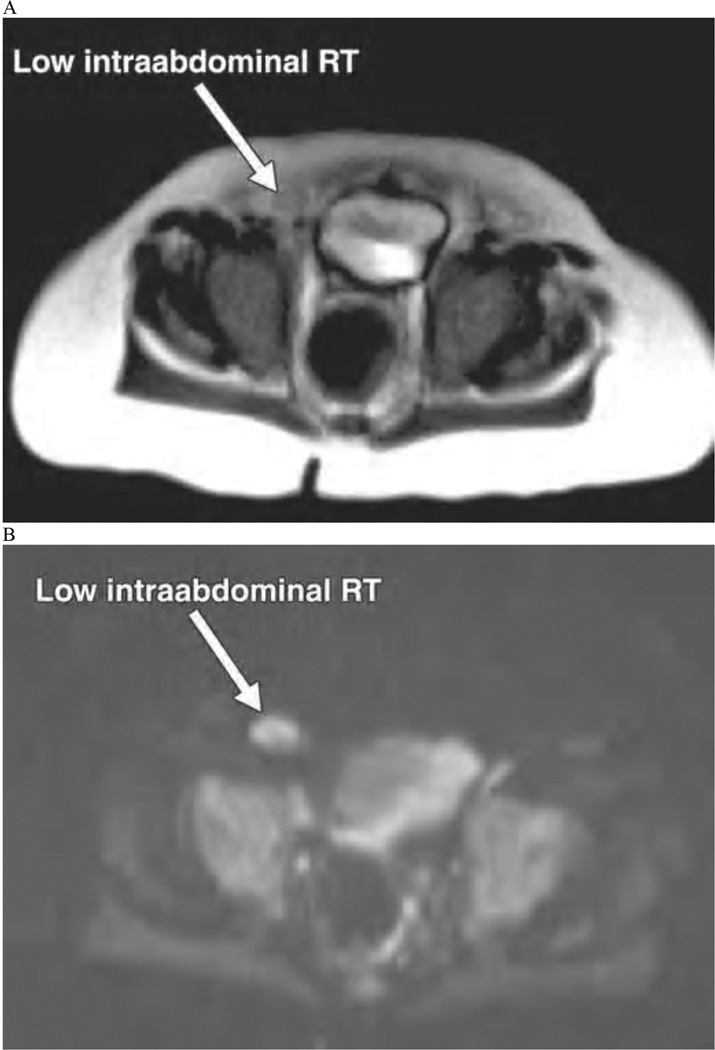

Unlike CT, MRI does not involve ionizing radiation and thus makes it a more attractive imaging modality for pediatric patients. However, MRI is expensive, not as readily available, and often requires that children are sedated or anesthetized. Undescended testes have similar MR signal characteristics to scrotal testes: there is low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high intensity of T2 weighted images (Figure 2). Miyano also reported that coronal images are the best plane for identification of undescended testes.[35] A number of studies have evaluated the diagnostic performance of MRI evaluation of undescended testes. In 1999, Yeung et al. reported the gadolinium-enhanced MRI identified 20 of 21 non-palpable testes of which 4 were intra-abdominal and 8 were intracanicular nubbins. These findings demonstrated that MRI had a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 100%, respectively. From this, the authors conclude that laparoscopy could have been avoided in 78% of patients who had pre-operative identification of inguinal testes or nubbins.[36] However, even for MRI, which has greater sensitivity and specificity compared to ultrasound, not identifying a testis does not completely exclude its absence.[35, 37]

Figure 2. MRI evaluation of non-palpable testes.

10-month-old boy with low intraabdominal nonpalpable undescended right testis (RT). A) T2-weighted MR image shows isointense testis close to internal ring. B) Diffusionweighted MR image with b value of 800 s/mm2 shows markedly hyperintense testis. 7-year-old boy with high intraabdominal nonpalpable undescended left testis (LT). C) T2-weighted MR image indistinctly shows isointense testis adjacent to iliac vessels. D) Diffusion-weighted MR image with b value of 400 s/mm2 clearly shows markedly hyperintense testis among loops of small bowel. (originally published in AJR Am J Roentgenol 195:W268–273, 2010; permission for reproduction has been requested)

This is supported by the findings of Kanemoto et al. who reported that MRI had a sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 79%, respectively.[38] More contemporary studies that have utilized conventional MRI in conjunction with diffusion weighted MRI to identify non-palpable testes have demonstrated similar performance characteristics. In this series, conventional MRI had a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 87.5%. When combined with diffusion-weighted imaging, the sensitivity increased marginally to 89.5% and the specificity remained the same. There was some inter-observer variability between the radiologists interpreting the MRIs.[19]

Economic Impact

Imaging is expensive. In the Medicare population, diagnostic imaging adds significantly to annual health care expenditures and is growing faster than any other physician-ordered service.[39, 40] Population-based studies assessing the economic impact of diagnostic imaging in children have not yet been performed. It is likely that the pediatric population mirrors the increasing use of and cost of imaging seen in the adult population. Charges vary by patient insurance status, region of the country, and whether the exam was performed in the hospital outpatient imaging department or in a freestanding imaging center.

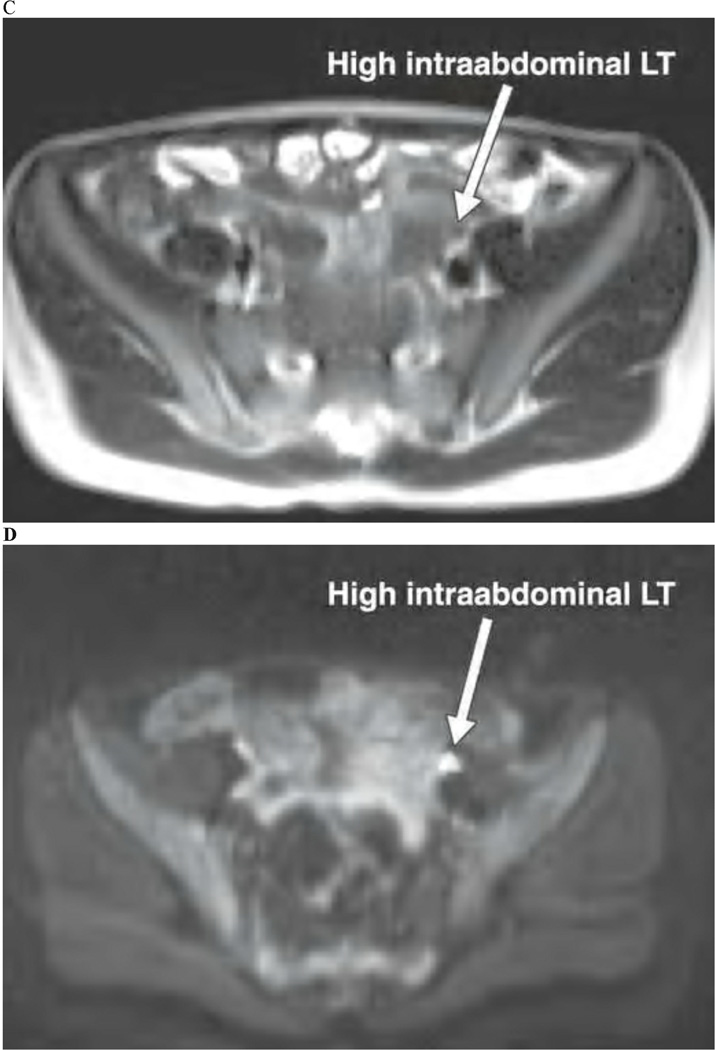

The need for studies that assess the cost of imaging is becoming more apparent and acute. It seems likely that in the short term that health care expenses will increase after implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.[41] Consequently, physicians and others in health care must develop new ways to decrease costs and improve resource utilization. In 2010, Brody, a medical ethicist, proposed that medical specialties identify and recommend against using heavily utilized and expensive diagnostic tests that offer little benefit for whom they are ordered.[42] Ultrasound evaluation of cryptorchidism, which its associated heavy utilization and poor diagnostic performance, meets these criteria. We recommend against routinely using ultrasound to evaluate children with cryptorchidism and propose that the diagnostic algorithm for the evaluation of a boy with cryptorchidism consist of physical exam and surgical evaluation (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Suggested algorithm for evaluation and treatment of a boy with cryptorchidism without the need for imaging.

Obese patients

In a survey of a national sample of general pediatricians, Tasian et al. observed that only 11% of pediatricians reported that an obese child was a factor influential in ordering ultrasound. However, obesity has been cited as a factor making detection of the undescended testis on physical exam more difficult and some authors have recommended MRI be used to localize testes in obese patients.[43, 44] In 2009, Breyer et al. classified patients by BMI and determined the ability of physical exam in the office and physical exam under anesthesia to predict operative findings. The overall predictive value of physical exam under anesthesia was less than 82%. While office physical exam was more reliable in non-obese patients, the accuracy of physical exam under anesthesia was similar between obese and non-obese patients.[45] Because all children with persistence of undescended testes require surgery, the equal ability of the physical exam under anesthesia to localize testes in obese patients, and the low-operative risk of laparoscopy, pre-operative imaging in obese boys with cryptorchidism is likely not necessary.

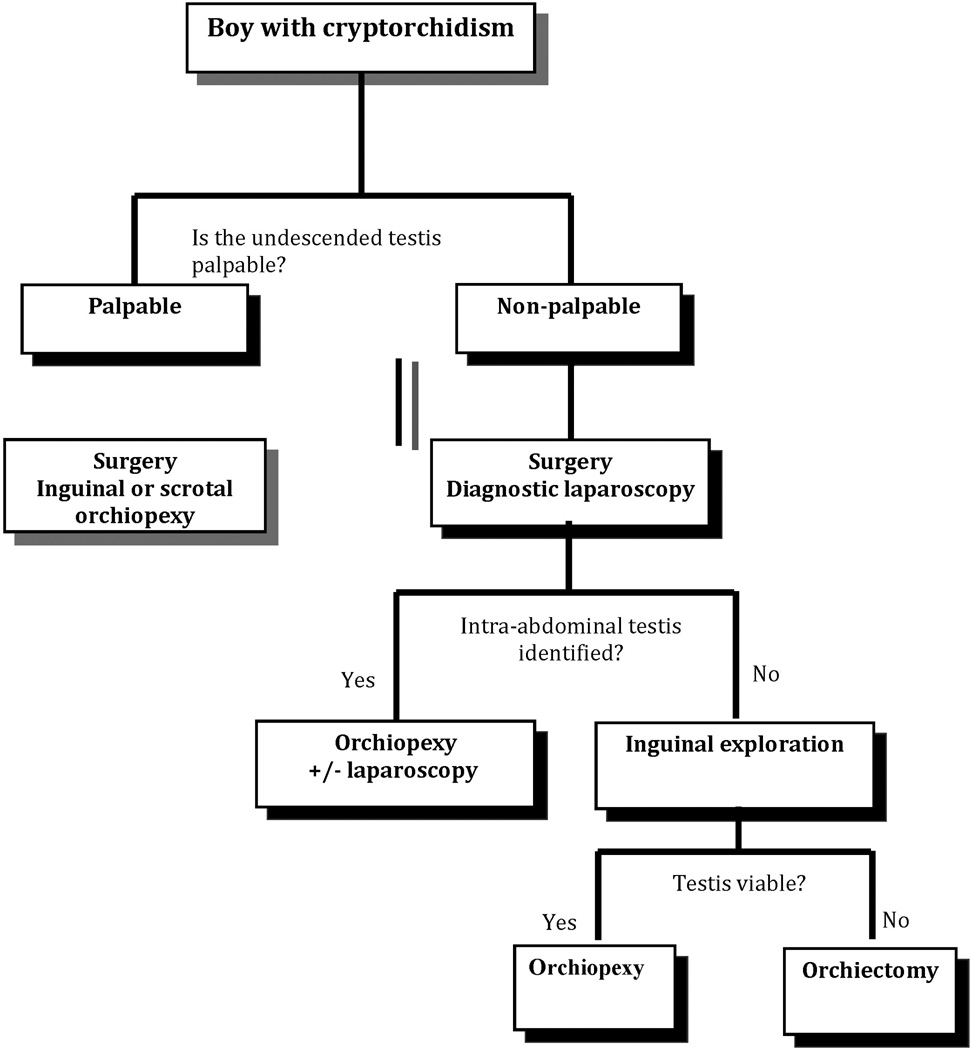

Ambiguous genitalia

Patients with undescended testes and ambiguous genitalia should have diagnostic imaging evaluation given the increased incidence of disorders of sexual development (DSD) in this cohort. For example, a presumed male with a normal phallus and bilateral nonpalpable testes requires a karyotype and sonogram to identify possible Mullerian structures, which would be seen in a XY female with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (Figure 4). It is critical to identify patients with DSD in order to make an accurate diagnosis of the specific disorder and to facilitate early multi-disciplinary care, which is crucial to the appropriate psychosocial development of these children. Identification of these patients will also avoid inappropriate surgery and, in the appropriate setting, allow early removal of precancerous gonads.[46–48]

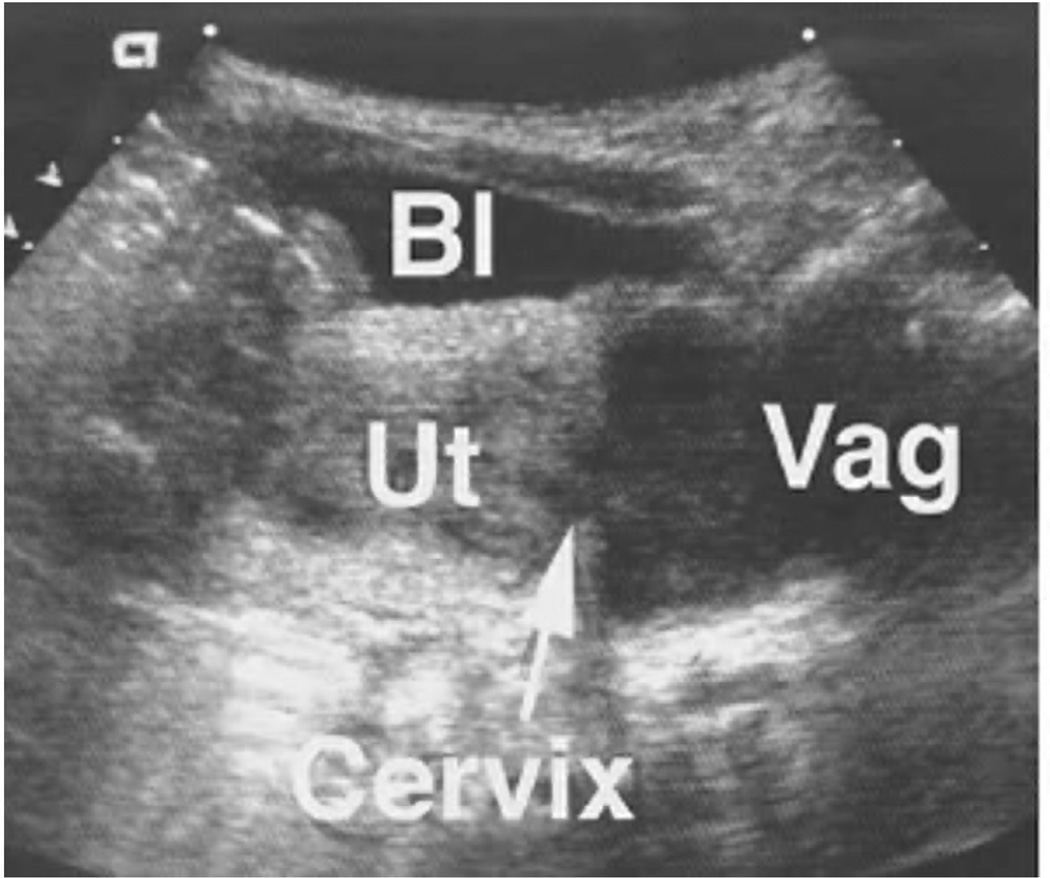

Figure 4. Neonate with ambiguous genitalia.

Examination of this patient (A) revealed a phallus, a hypoplastic empty scrotum, and non-palpable gonads. The karyotype was XX and abdominal-pelvic ultrasound (B) demonstrated Mullerian structures. Serum assays of adrenal steroids established the diagnosis of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Bl = urinary bladder, Ut = uterus, Vag = vagina

In addition to those with ambiguous genitalia, boys with both hypospadias and cryptorchidism have an approximately 30% likelihood of having DSD.[49] This risk increases 3-fold in those children with proximal hypospadias and non-palpable testes.[50] The disorders of sexual development identified in this group included mixed gonadal dysgenesis, incomplete testicular feminization, and ovotesticular DSD. Given the significant risk of having DSD, ultrasound is indicated in this population to look for the presence of a uterus and secondary assessment of testes. MRI can be obtained as clinically indicated.

In some children with DSD, one or both testes may be descended into the scrotum. Only 10% of boys with persistent Müllerian duct syndrome have bilateral nonpalpable testes; the remainder has at least one palpable testis. Therefore since ultrasound is not routinely performed for unilateral cryptorchidism, early diagnosis of this rare disorder may be missed.[51]

Reoperation

Identification of the testis can be quite difficult in children who have previously had inguinal or scrotal surgery. Due to the scarring, increased risk of injury to the testis, and limited mobility of the spermatic cord, accurate pre-surgical localization of the testis can provide the surgeon with anatomic knowledge that can be used to tailor the operative approach. However, in the setting of a child who has previously undergone inguinal or scrotal surgery, the specificity of ultrasound decreases significantly. Kullendorff et al. reports that of the 8 children who had previously been operated, the ultrasound findings in 5 were uninterpretable or were discordant with the operative findings.[25] In 2008, Kattak et al. confirmed these findings in a series of 11 boys undergoing reoperative orchiopexy following failed primary orchiopexy or other inguinal surgery. Physical exam detected approximately 50% of potentially palpable testes while ultrasound found only 36% of the testes. In one patient, no testicle was found at surgical exploration.[52] Although definitive studies have not yet been performed, it is our opinion that MRI, which has relatively high sensitivity and specificity in localizing testes, might be indicated in this population to guide the surgeon to the testis given the unreliable physical exam and obscured tissue plains in previously operated patients. We hope that future studies can provide evidence to test this hypothesis.

Conclusions

Diagnostic imaging has no role in the routine evaluation of boys with undescended testes. Given the poor diagnostic performance of ultrasound and its high utilization in this setting, we recommend that efforts be developed to discourage its routine use in the evaluation of a boy with cryptorchidism. Ultrasound is an appropriate screening evaluation for children with ambiguous genitalia or hypospadias and cryptorchidism. Future studies should examine whether pre-operative MRI has utility in re-operative orchiopexy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Cryptorchidism: a prospective study of 7500 consecutive male births, 1984-8. John Radcliffe Hospital Cryptorchidism Study Group. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:892–899. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.7.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acerini CL, Miles HL, Dunger DB, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of congenital and acquired cryptorchidism in a UK infant cohort. Arch Dis Child. 2009 doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.150219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee PA, O'Leary LA, Songer NJ, et al. Paternity after bilateral cryptorchidism. A controlled study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:260–263. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170400046008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasian GE, Hittelman AB, Kim GE, et al. Age at orchiopexy and testis palpability predict germ and Leydig cell loss: clinical predictors of adverse histological features of cryptorchidism. J Urol. 2009;182:704–709. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettersson A, Richiardi L, Nordenskjold A, et al. Age at surgery for undescended testis and risk of testicular cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1835–1841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kogan SJ, Tennenbaum S, Gill B, et al. Efficacy of orchiopexy by patient age 1 year for cryptorchidism. J Urol. 1990;144:508–509. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39505-8. discussion 512-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park KH, Lee JH, Han JJ, et al. Histological evidences suggest recommending orchiopexy within the first year of life for children with unilateral inguinal cryptorchid testis. Int J Urol. 2007;14:616–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smolko MJ, Kaplan GW, Brock WA. Location and fate of the nonpalpable testis in children. J Urol. 1983;129:1204–1206. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tekgul S, Riedmiller H, Gerharz E, et al. Guideline on paediatric urology, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 10.McEachern R, Houle AM, Garel L, et al. Lost and found testes: the importance of the hCG stimulation test and other testicular markers to confirm a surgical declaration of anorchia. Horm Res. 2004;62:124–128. doi: 10.1159/000080018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gapany C, Frey P, Cachat F, et al. Management of cryptorchidism in children: guidelines. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138:492–498. doi: 10.4414/smw.2008.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore RG, Peters CA, Bauer SB, et al. Laparoscopic evaluation of the nonpalpable tests: a prospective assessment of accuracy. J Urol. 1994;151:728–731. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lotan G, Klin B, Efrati Y, et al. Laparoscopic evaluation and management of nonpalpable testis in children. World J Surg. 2001;25:1542–1545. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papparella A, Parmeggiani P, Cobellis G, et al. Laparoscopic management of nonpalpable testes: a multicenter study of the Italian Society of Video Surgery in Infancy. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:696–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snodgrass WT, Yucel S, Ziada A. Scrotal exploration for unilateral nonpalpable testis. J Urol. 2007;178:1718–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellsworth PI, Cheuck L. The lost testis: Failure of physical examination and diagnostic laparoscopy to identify inguinal undescended testis. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5:321–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.02.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnbjornsson E, Mikaelsson C, Lindhagen T, et al. Laparoscopy for nonpalpable testis in childhood: is inguinal exploration necessary when vas and vessels are not seen? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1996;6:7–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1066456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaccara A, Spagnoli A, Capitanucci ML, et al. Impalpable testis and laparoscopy: when the gonad is not visualized. JSLS. 2004;8:39–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kantarci M, Doganay S, Yalcin A, et al. Diagnostic performance of diffusion-weighted MRI in the detection of nonpalpable undescended testes: comparison with conventional MRI and surgical findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W268–W273. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah A. Impalpable testes--is imaging really helpful? Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:720–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baillie CT, Fearns G, Kitteringham L, et al. Management of the impalpable testis: the role of laparoscopy. Arch Dis Child. 1998;79:419–422. doi: 10.1136/adc.79.5.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tasian GE, Yiee JH, Copp HL. Imaging use and cryptorchidism: determinants of practice patterns. J Urol. 2011;185:1882–1887. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martelli A, Bercovich E, Soli M, et al. A new use of echography: the study of the undescended testicle. Urologia. 1977;44:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedland GW, Chang P. The role of imaging in the management of the impalpable undescended testis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:1107–1111. doi: 10.2214/ajr.151.6.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kullendorff CM, Hederstr√∂m E, Forsberg L. Preoperative Ultrasonography of the Undescended Testis. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 1985;19:13–15. doi: 10.3109/00365598509180215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss RM, Carter AR, Rosenfield AT. High resolution real-time ultrasonography in the localization of the undescended testis. J Urol. 1986;135:936–938. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45928-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elder JS. Ultrasonography is unnecessary in evaluating boys with a nonpalpable testis. Pediatrics. 2002;110:748–751. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tasian GE, Copp HL. Diagnostic performance of ultrasound in nonpalpable cryptorchidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;127:119–128. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merguerian PA, Mevorach RA, Shortliffe LD, et al. Laparoscopy for the evaluation and management of the nonpalpable testicle. Urology. 1998;51:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denes FT, Saito FJ, Silva FA, et al. Laparoscopic diagnosis and treatment of nonpalpable testis. Int Braz J Urol. 2008;34:329–334. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382008000300010. discussion 335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh TJ, Dall'Era MA, Croughan MS, et al. Prepubertal orchiopexy for cryptorchidism may be associated with lower risk of testicular cancer. J Urol. 2007;178:1440–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.166. discussion 1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JK, Glazer HS. Computed tomography in the localization of the nonpalpable testis. Urol Clin North Am. 1982;9:397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JK, McClennan BL, Stanley RJ, et al. Utility of computed tomography in the localization of the undescended testis. Radiology. 1980;135:121–125. doi: 10.1148/radiology.135.1.6102403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2078–2086. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyano T, Kobayashi H, Shimomura H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for localizing the nonpalpable undescended testis. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:607–609. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90718-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeung CK, Tam YH, Chan YL, et al. A new management algorithm for impalpable undescended testis with gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance angiography. J Urol. 1999;162:998–1002. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)68046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maghnie M, Vanzulli A, Paesano P, et al. The accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography compared with surgical findings in the localization of the undescended testis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:699–703. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170070037006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanemoto K, Hayashi Y, Kojima Y, et al. Accuracy of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of non-palpable testis. Int J Urol. 2005;12:668–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dinan MA, Curtis LH, Hammill BG, et al. Changes in the use and costs of diagnostic imaging among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer, 1999–2006. JAMA. 2010;303:1625–1631. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iglehart JK. Health insurers and medical-imaging policy--a work in progress. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1030–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0808703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foster R. Proposed by the Senate Majority Leader on November 18, 2009. Department of Health & Human Services; 2009. Estimated Financial Effects of the “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2009,”; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brody H. Medicine's ethical responsibility for health care reform--the Top Five list. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:283–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Savage JG. Avoidance of inguinal incision in laparoscopically confirmed vanishing testis syndrome. J Urol. 2001;166:1421–1424. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200110000-00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Filippo RE, Barthold JS, Gonzalez R. The application of magnetic resonance imaging for the preoperative localization of nonpalpable testis in obese children: an alternative to laparoscopy. J Urol. 2000;164:154–155. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200007000-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breyer BN, DiSandro M, Baskin LS, et al. Obesity does not decrease the accuracy of testicular examination in anesthetized boys with cryptorchidism. J Urol. 2009;181:830–834. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berkmen F. Persistent mullerian duct syndrome with or without transverse testicular ectopia and testis tumours. Br J Urol. 1997;79:122–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.27226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muller J, Skakkebaek NE, Ritzen M, et al. Carcinoma in situ of the testis in children with 45,X/46,XY gonadal dysgenesis. J Pediatr. 1985;106:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80670-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manuel M, Katayama PK, Jones HW., Jr The age of occurrence of gonadal tumors in intersex patients with a Y chromosome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;124:293–300. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajfer J, Walsh PC. The incidence of intersexuality in patients with hypospadias and cryptorchidism. J Urol. 1976;116:769–770. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)59004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaefer M, Diamond D, Hendren WH, et al. The incidence of intersexuality in children with cryptorchidism and hypospadias: stratification based on gonadal palpability and meatal position. J Urol. 1999;162:1003–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)68048-0. discussion 1006–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brandli DW, Akbal C, Eugsster E, et al. Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome with bilateral abdominal testis: surgical approach and review of the literature. J Pediatr Urol. 2005;1:423–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khattak ID, Zafar A, Khan IA, et al. Re-do orchidopexy in a general surgical unit-reliability of clinical diagnosis and the outcome of surgery. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008;20:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]