Abstract

Objective

Many adolescents with substance use problems show poor response to evidence based treatments. Treatment outcome has been associated with individual differences in impulsive decision making as reflected by delay discounting (DD) rates (preference for immediate rewards). Adolescents with higher rates of DD were expected to show greater neural activation in brain regions mediating impulsive/habitual behavioral choices and less activation in regions that mediate reflective/executive behavioral choices.

Method

Thirty adolescents being treated for substance abuse completed a DD task optimized to balance choices of immediate versus delayed rewards and a control condition accounted for activation during magnitude valuation. A group independent component analysis on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) time courses identified neural networks engaged during DD. Network activity was correlated with individual differences in discounting rate.

Results

Higher discounting rates were associated with diminished engagement of an executive attention control network involving the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal cortex, cingulate cortex, and precuneus. Higher discounting rates were also associated with less deactivation in a “bottom up” reward valuation network involving the amygdala, hippocampus, insula, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. These 2 networks were significantly negatively correlated.

Conclusions

Results support relations between competing executive and reward valuation neural networks and temporal decision making, an important potentially modifiable risk factor relevant for prevention and treatment of adolescent substance abuse.

Clinical trial registration information—The Neuroeconomics of Behavioral Therapies for Adolescent Substance Abuse; http://clinicaltrials.gov/; NCT01093898.

Keywords: adolescent substance abuse, delay discounting, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), neuroeconomics

Introduction

A primary model of decision making used to explain substance use behavior is intertemporal decision making or choices between two alternatives that occur at different points in time.1 There is a general tendency for rewards to lose value the farther away they are in the future, a phenomenon referred to as delay discounting. Delay discounting (DD) rates generally follow a hyperbolic function, in which reward valuation decreases very rapidly across short delays, and then more slowly across longer delays.2 DD is hypothesized to be particularly relevant to substance use because substance use can be characterized as a choice between the tangible and immediate rewards of consumption and the delayed rewards of abstinence. There is a large literature supporting the association between DD rate and adult and adolescent substance abuse onset and severity.1,3,4 Further, studies have reported worse adult and adolescent substance abuse treatment outcomes for high discounters.5–7 For example, we reported that treatment-enrolled teens with higher DD rates were less likely to achieve abstinence.8

Neural Mechanisms of Delay Discounting

A meta-analysis9 identified 25 regions of significant neural activation during DD tasks. Three primary regions of robust activation include value-related regions (ventral striatum), value consideration regions (medial prefrontal cortex), and future forecasting regions (posterior cingulate cortex). These regions are consistent with the valuation network proposed by Peters and Buchel,10 who also propose 2 additional networks important in DD: a cognitive control network, involving activation of the anterior cingulate cortex and reduced top-down regulation of the medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and a prospection/episodic imagery network, involving activity in the medial temporal lobe (hippocampus and amygdala). However, there are developmental differences between adolescent and adults in these regions that may impact DD. Adolescents show maturation similar to adults in limbic and paralimbic “bottom up” brain regions that function with respect to primary reinforcers;11,12 and slower maturation of the “top down” frontal and prefrontal cortex, which regulate executive function and decision making.11,13 This asymmetric development is theorized to be related riskier decision making among adolescents than adults.14,15 This combination of heightened neural response to reward and motivational cues and delayed behavioral and cortical control may contribute to adolescent preferences for immediate rewards.16

There are relatively few studies of neural mechanisms of DD in adolescence. Several studies have examined age-related functional and structural brain changes related to DD, and 2 have identified relations between neural function and structural connectivity and DD rates that were independent of age-related changes.17,18 For example, strengthening of functional coupling among the ventromedial (VM) PFC, ventral striatum (VS), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and the temporal lobe was associated with decreased discounting, suggesting that developing connectivity between the VMPFC and VS systems may account for individual differences in DD rates.17 Increased ventral PFC white matter organization is also associated with decreased DD rates.18 These results suggest that there may be individual brain and behavioral differences evident in adolescence that confer risk independent of developmental changes.

Several studies have also documented neural structural and activation differences between adolescent substance users and controls.19,20 There is longitudinal evidence that alcohol use in adolescence may negatively impact both memory and attention,21 and evidence of neural activation differences between substance users even at the earliest stages of tobacco use and demographically matched same age peers.22 However, most informative for treatment development is identifying the utility of individual neural differences among youth who display problem use and/or who meet diagnostic criteria in predicting individual differences in treatment relevant constructs such as decision making in order to ultimately improve treatment outcomes.

The current study was designed to identify individual differences in neural network activation related to decision making (DD) among adolescents with substance use problems. Adolescent substance users were assessed at treatment entry using laboratory and fMRI methods while making intertemporal choice decisions. Analyses explored relations between the neural processing patterns that occur when making choices between immediate and delayed rewards and DD rate. We hypothesized that the DD task would activate neural networks consistent with reward valuation and cognitive control, and that the patterns of activation in these networks would be correlated with individual differences in DD.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from 2 ongoing studies investigating behavioral treatments for adolescent substance abuse (Marijuana Trial and Alcohol Trial). A total of 52 subjects enrolled in the treatment studies during recruitment for the current study. Two teens refused screening and 9 screened eligible but declined to participate in this study. A total of 6 subjects were not eligible for MRI due to metal in their body (most often braces), and 2 reported claustrophobia and were not scanned. In addition, data for 3 scanned subjects were removed from the dataset due to head movement (n=1), incomplete discounting data (n=1), and removal from scanner due to claustrophobia (n=1). A total of 30 scanned subjects were included in the analyses. These participants were ages 12 to 18 (M age = 15.7; SD =1.7; 80% male; 63.3% Caucasian and 36.7% African American).

Teens in the Marijuana Trial (n=14) reported marijuana use in the past 30 days or provided a tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)–positive urine test, plus met DSM criteria for marijuana abuse or dependence. Teens in the Alcohol Trial (n=16) reported alcohol use in the past 30 days, and either met DSM criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence or had had one binge episode (≥5 drinks in one day) in the past 90 days. A bachelor’s level research assistant administered the Vermont Structured Diagnostic Interview (VSDI23) to assess DSM-IV substance use and mental health disorders. Interviewers were trained to administer the instruments via manual review, observation, and supervised practice interviews. The interview has demonstrated good psychometric properties.23 Binge drinking was assessed using the Time-Line Follow-Back method24 for 90 days prior to intake. Alcohol-dependent youth were excluded from the Marijuana Trial and were assigned to the Alcohol Trial. Youth eligible for both trials were assigned to the Alcohol Trial. Eighteen (60%) adolescents met criteria for marijuana abuse or dependence only, 3 (10%) met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence only, 6 (20%) met criteria for marijuana abuse or dependence and alcohol abuse or dependence, and 3 (10%) reported binge drinking only. On average, adolescents reported smoking marijuana on 9.40 days (SD = 9.66) and drinking alcohol on 1.87 days (SD = 2.97) in the 30 days prior to the intake appointment. In addition, adolescents reported drinking an average of 3.29 (SD = 4.74, range = 0–16) drinks per drinking day in the 30 days prior to the intake appointment. Based on caregiver and/or teen report, subjects also met criteria for one or more of these disorders: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; caregiver: 36.7%, teen: 13.3%; caregiver and/or teen: 36.7%), conduct disorder (caregiver:16.7%, teen: 6.7%; caregiver and/or teen: 16.7%), oppositional defiant disorder (caregiver: 36.7%; teen: 16.7%; caregiver and/or teen:43.3%), major depression (caregiver: 6.7%; teen: 13.3%; caregiver and/or teen:16.7%), and generalized anxiety disorder (caregiver: 10.0%; teen: 13.3%; caregiver and/or teen:16.7%). Tables S1 and S2, available online, provide individual and group level demographic, DD, diagnostic, and substance use data.

Measurement of Delay Discounting

A delay discounting (DD) task was administered to each subject immediately prior to MRI acquisition using a computerized program. Adolescents were asked to choose between receiving a (hypothetical) $1,000 after a delay and receiving a smaller amount of money immediately. For each delay, the subject was presented with six consecutive decision-making trials. The delay intervals were one day, one week, one month, 6 months, one year, 5 years, and 25 years. For each delay, the amount of money offered “now” started at $500, and the amount increased or decreased based on the subject’s choice for trials 2–6.

DD rate was estimated using Mazur’s2 equation: Vd = V / (1 + kD), where Vd represents the discounted value at D delay, V is the undiscounted amount, and k is the estimated discounting parameter. High values of k indicate greater discounting or preference for immediate rewards. Vd was derived by calculating individuals’ indifference point, which is the value of the immediate reward that is considered as attractive as the $1,000 delayed reward. Indifference points were calculated for each delay and fit to the hyperbolic model of DD rate (k) and then log transformed (lnk).

fMRI Procedures

Delay Discounting Task

The DD task completed in the scanner was optimized for functional neuroimaging, using an event-related trial design. Functional T2*-weighted echoplanar images (EPIs) were acquired using a Philips Achieva 3.0 Telsa X-series MRI and an 8-channel head coil (Philips Healthcare, USA) with the following parameters: 3×3×3 mm3 isotropic voxels, repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, field of view (FOV) = 240mm×240mm, flip angle (FA) = 90°, matrix = 80×80, 37 slices. T1-weighted structural images were acquired for alignment and tissue segmentation purposes using an MPRAGE sequence (matrix=192×192, 160 slices, TR/TE/FA=2600 msec/3.02 msec/80, final resolution=1×1×1 mm3). In the scanner, the subject was presented with discounting trials at each of 4 delay intervals (one month, 6 months, 1 year, and 5 years) plus control trials (choice between 2 different amounts of money, both received “today”) presented in a randomized sequence. The fMRI DD task used each individual’s indifference points from the pre-MRI DD task as the starting value for the smaller, sooner (SS) amount at each delay. This starting point was designed to produce equal numbers of SS and larger, later (LL) choices at each delay, making the task similarly challenging for all subjects. The smaller value was always offered “today” and presented on the left side of the screen and $1,000 was offered at 1 of the delay intervals and displayed on the right. The subject made a decision by pressing 1 of 2 buttons on a button box corresponding with their choice. Following the decision, the selected option was surrounded with a bold rectangle for one second to confirm that a response was recorded. Choices involved the same delay intervals and LL amount ($1,000) for all subjects, with variable SS amounts based on the subject’s starting indifference point and subsequent choices at each delay.

The task was divided into two runs, each consisting of 2 sets of 25 trials and 3 sets of rest periods (25 seconds), for a total of 100 decision making trials. The task was self-paced and lasted approximately 20 minutes. Each set of 25 trials consisted of 5 trials of each of the four delays and 5 control trials with a fixed interstimulus interval of 5 seconds. The subject’s response on each trial of each delay determined whether or not the smaller amount offered “today” on the next trial of that delay increased (prior selection of $1,000) or decreased (prior selection of smaller amount) (algorithm available on request from first author).

Data Processing and Analyses

Image preprocessing and statistical analyses were performed using Analysis of Functional Neuroimages (AFNI; afni.nimh.nih.gov) software. Functional images underwent the following preprocessing steps: slice time correction, deobliquing, motion correction, despiking, alignment to the subject’s structural image, warping to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standardized space, removal of signal fluctuations in white matter and cerebral spinal fluid from voxel time courses, spatial smoothing with a 6 mm full-width at half-maximum Gaussian kernel, scaling to percent signal change, and, for voxel-wise contrasts, masking of non-gray matter voxels with masks created using FSL software from the subject’s structural image.

Voxel-wise general linear model analyses were conducted in AFNI. Decision trials were modeled as epochs beginning at the presentation of choices and ending with a response. Participants’ mean response time ranged from 1.69 to 6.96 seconds (M=3.31, SD=1.16). Neural activation associated with making 2 types of decisions, SS or LL, was compared to that of control ‘no delay’ trials (CON) in voxel-wise contrasts. In addition, DD rate (lnk value) was correlated with neural activity while making DD decisions in the scanner (i.e., SS vs. CON; LL vs CON). Results from whole brain voxel-wise analyses were subjected to multiple comparison correction based on 10,000 Monte-Carlo simulations conducted using the 3dClustSim command in AFNI. To obtain a corrected p-value of 0.05, only clusters composed of 17 or more voxels surviving a p-value threshold of 0.005 were considered significant.

In addition, a group independent component analysis (ICA) on fMRI timecourses25 was conducted with Group ICA of fMRI toolbox (GIFT) in Matlab,26 solving for 20 components. ICA was conducted with the infomax algorithm and the following selected options: data entry (2 runs per subject), no dummy scans, using spatial temporal regression for back-reconstruction, removal of image mean at each timepoint, standard PCA with stacked datasets, 2-step data reduction, no batch estimation, and scaling values to z-scores. ICA was repeated 5 times using the ICASSO algorithm to identify the most reliable and stable components across all 5 ICA iterations.

For each subject, the experimental design was convolved with the SPM27 canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF) to estimate the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal response for 3 decision types: SS, LL, and CON. Estimated BOLD responses for each trial type were modeled in regression analyses in GIFT as predictors of each component time course, with 6 directions of head motion included as covariates. This method is analogous to the general linear model approach to voxel-wise analysis of fMRI task data, except that data were reduced from thousands of voxels to 20 independent components. The association of each component with each trial type (SS, LL, and CON) was represented by beta estimates and t-values. Thirteen components representing head motion, noise and sensory processing were excluded from further analysis. For the remaining 7 components, contrast values were calculated for each subject for SS-CON trials and LL-CON trials using beta estimates from the regression analysis. A positive contrast value indicates that the network was more active during SS or LL than during CON trials, and a negative contrast value indicates that the network was more active during CON than SS or LL trials. Individual SS-CON and LL-CON contrast values for each of the 7 retained components were correlated with lnk. Additional analyses controlled for age, sex, and past 30 day substance use (number of alcoholic drinks, number of days of marijuana and/or K2 (synthetic cannabis) use, and number of days of tobacco use). We hypothesized that adolescents with substance abuse problems who have higher discounting rates, reflecting a greater preference for immediate rewards, would show greater activation in neural regions mediating impulsive/habitual behavioral choices and less activation in neural regions mediating more reflective/executive behavioral choices compared to individuals exhibiting lower rates of discounting.

Results

Localization of Whole Brain Activations Related to Intertemporal Choice Behavior

Pair-Wise Contrasts

Voxel-wise, brain-wide planned contrasts of SS-CON and LL-CON choices resulted in distributed neural activations typically attributed to impulsive and deliberative choice behavior. Task-related activations are reported in the Tables S3 and S4, available online, and represent those that survived a cluster-level correction for multiple comparisons.

Smaller/Sooner versus Control

Compared to the judgment of relative monetary amount in the CON trials, the choice of SS rewards was associated with activation of dorsomedial, dorsolateral and polar prefrontal cortex, precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, fusiform and lingual gyri, superior temporal gyrus, cerebellum, and paracentral lobule (Table S3, available online). Relative to CON choices, SS choices were associated with less activation of the inferior parietal cortex, right precentral gyrus extending into the inferior frontal cortex, bilateral parahippocampal gyri, and temporal and parietal cortex.

Larger/Later versus Control

Compared to CON choices, the choice of LL rewards was associated with activation of the pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA), polar and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, cuneus extending into the inferior occipital gyrus, cerebellum, posterior cingulate cortex, bilateral dorsal caudate nucleus, and parietal cortex (Table S4, available online). Choice of LL rewards relative to CON choices were associated with less activation of the bilateral middle temporal gyrus, right inferior frontal cortex extending into the amygdala, right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal cortex, cuneus, middle cingulate cortex, left inferior frontal cortex, and left amygdala.

Smaller/Sooner versus Larger/Later

Compared to the LL decision trials, SS choices were associated with greater activation of the right lingual gyrus (7.5, −70.5, −6.5 mm) and occipital cortex (34.5, −85.5, 17.5 mm). No other relative activations for LL versus SS trials survived multiple comparison correction.

Regression Analyses

Brain-wide analyses assessed the relationship between individual differences in discounting rate (lnk) and the magnitude of task-related regional brain activation. Significantly correlated brain regions (p < 0.05, corrected) are reported in Table S5, available online. For SS-CON, lnk was significantly correlated with activation of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, bilateral middle/posterior insula, right posterior superior temporal sulcus, precuneus, and posterior parietal cortex. For LL-CON, lnk was significantly correlated with activation of the bilateral middle insula, superior and middle temporal gyri, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, and precuneus. For SS-LL, no regions of activation were significantly correlated with lnk following whole-brain correction.

Group ICA results

Of the seven components of activation assessed in correlation analyses for their relationship to individual differences in discounting rates, two components were significantly correlated with lnk (p<0.05), though neither survived a Bonferroni correction for the number of components tested (p<.05/[2 contrast types (SS vs. CON and LL vs. CON) × 7 components=14]=.00357). Those 2 components are described below, and activation patterns for the other 5 networks are shown in Figure S1, available online.

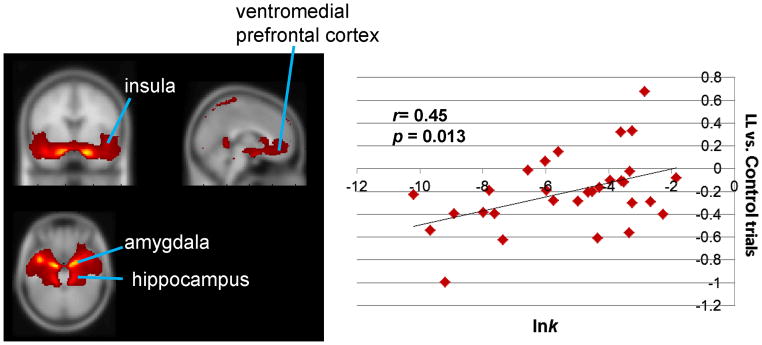

Valuation Network

As shown in Figure 1b, lnk positively correlated (r=0.45, p=0.013) with relative activation for LL versus CON choices for a component comprising the amygdala and hippocampus, paralimbic cortex involving the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, insula and posterior cingulate cortex, and the ventral striatum (see Figure 1a). These coactivated regions are involved in motivation, valuation, prospection, and salience processing,10,28,29 suggesting that this component represents a valuation network. This association remained after controlling for age, sex, and substance use frequency (r=0.56, p=0.004).

Figure 1.

Valuation network: larger, later (LL) choice trials versus control trials. Note: (A) Network map: Depicted regions were coactivated by task, as identified from group independent component analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging time course. (B) Correlation between log-transformed delay discounting rate (lnk) and network activation. Individual contrast values for LL versus control trials (positive value indicates greater activity for LL versus control; negative value indicates less activity for LL versus control) are on the y axis; individual values of lnk are on the x axis.

Cognitive Control/Executive Function Network

As shown in Figure 2b, lnk negatively correlated (r=−0.41, p=0.023) with activation for SS-CON choices in a bilateral frontal-parietal network (right>left). Coactivated regions included the ventrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, superior parietal cortex, and precuneus (see Figure 2a). These regions are involved in executive functions such as goal representation, cognitive control, and response selection.10,30,31 This association remained after controlling for age, sex, and substance use frequency (r=−0.44, p=0.029).

Figure 2.

Cognitive control/executive function network: smaller, sooner (SS) choice trials versus control trials. Note: (A) Network map. A second network of coactivated brain regions as determined from group independent component analysis of functional neuroimaging time courses. (B) Correlation between log-transformed delay discounting rate (lnk) and network activation. Individual contrast values for SS versus control trials (positive value indicates greater activity for SS versus control; negative value indicates less activity for SS versus control) are on the y axis; individual values of lnk are on the x axis.

Network Correlations

To assess the role of functional network interactions in DD, the correlation was computed between activity in these 2 networks during decision making trials (mean activation during SS and LL choices). As shown in Figure 3, activity in these networks was highly negatively correlated (r=−0.67, p<.0001), suggesting that the two networks function in a reciprocal manner in contributing to individual differences in DD.

Figure 3.

Correlation between valuation and cognitive control networks. Note: Individuals’ mean brain activity for the cognitive control network (x-axis) plotted against mean brain activity for the valuation network (y-axis) for all decision making trials (irrespective of choice) versus control trials.

Discussion

Whole brain pairwise contrasts indicated extensive activations broadly consistent with many other delay discounting fMRI studies.9 Group ICA yielded 7 components reflecting theoretically consistent regions of neural coactivation during all trials. Activation in two components or networks showed significant relations with individual DD rates. However, neither effect survived the Bonferroni correction, supporting the need to replicate these findings. One, a putative valuation network, showed ventral limbic activations involving the amygdala and hippocampus, paralimbic cortex involving the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, insula and posterior cingulate cortex, and the ventral striatum. These regions are involved in multiple cognitive functions integral to intertemporal decision making, including valuation, prospection/future forecasting, and episodic imagery.9,10 Others have reported similar relations between ventral striatal activity and adolescent risk taking.32 These findings uniquely demonstrate via ICA that these separate neural processes related to DD are organized into a higher-order network. Further, activation of this higher-order network predicted individual differences in DD rates. There was less activity among lower discounters in this “bottom up” reward valuation network when choosing LL (compared to simple immediate reward magnitude valuation) and lesser suppression of activity among higher discounters.

Activation in a network that likely reflects cognitive control and executive function was also related to individual DD rates. Similar to the cognitive control, regulatory network proposed by Peters and Buchel,10 this network showed bilateral frontal-parietal activations encompassing the ventrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, superior parietal cortex, and precuneus. Higher DD teens show less engagement in this executive network than lower DD teens during impulsive decision making, with SS choices reflecting less involvement of this cognitive control network for higher discounters. In other words, SS choices involve more executive processing for lower discounters.

The Group ICA results are consistent with 2 independent neural processing networks mediating the valuation and choice processes related to DD with decreasing activation of a frontal-parietal network and increasing activation of a limbic-paralimbic network both predicting greater discounting. These results were consistent with a study showing that higher risk taking on a gambling task was associated with reduced activity in control-related regions in the dorsal medial PFC and greater activity in reward (valuation) regions in the VMPFC among nonreferred adolescents.33 In the current study, similar relations were observed between DD rate and activation in these regions in the dorsal medial PFC (integrated into a larger cognitive control network) and in these regions in the VMPFC (integrated into a larger valuation network).

The strong negative correlation observed between the 2 networks suggests that the balance in activity between these networks influences temporal decision making. Several studies have suggested that there are interacting (competing) networks involved in reward valuation,34,35 with an evolutionarily older impulsive system (limbic and paralimbic regions) primarily involved in the valuation of immediate rewards, and the more recently developed executive system (prefrontal regions) involved in the consideration of the future and the selection of delayed rewards. The balance (or imbalance) in activation and connectivity between these competing valuation systems is hypothesized to underlie individual DD rates.1 Alternatively, others have suggested that reward valuation is better conceptualized as reflecting the activity of a single neural network that tracks subjective value at all delays.36 Because we collapsed across all delays, we cannot specifically address the role of delay in the activity of these networks. However, our results do support the involvement of 2 distinct neural networks that function in opposition during temporal decision making, with lower discounters showing greater activity in executive control regions and greater suppression of activity in valuation regions.

The period of mid adolescence (ages 14–16) appears to be the time of greatest developmental change in DD,15 suggesting that adolescence might be a unique and ideal time to attempt to reduce DD. Interventions like contingency management that attempt to shift preferences to delayed rewards might be most effective during this developmental period. The use of rewards may also influence decision making and its neural correlates among adolescent substance users. For example, adolescents with substance use problems have shown greater activation than control adolescents in prefrontal cognitive control regions an inhibition task when rewards were available.37 Similarly, the use of rewards facilitates cognitive control among adolescents to a greater extent than for adults.38 Thus, treatment approaches that offer consistent and tangible rewards might be particularly effective in adolescence, and the mechanism for such enhanced effects might be enhanced engagement of cognitive control or executive brain regions related to DD.

Working memory training may also influence neural function related to DD leading to reductions in substance use. For example, individual differences in DD among healthy adults are correlated with activity in the left anterior prefrontal cortex while performing a working memory task.39 Further, Bickel et al.40 showed that working memory training resulted in reductions in DD rates among adult stimulant abusers. Similarly, Houben et al.41 showed working memory training led to significant reductions in alcohol intake among problem drinkers. These results suggest that interventions involving working memory training might enhance treatment response by influencing the activity or functional balance of neural networks that underlie DD.

Overall, this study was intended as an initial exploratory study, and these results should be considered preliminary until they are replicated with a larger, independent sample. Beyond the tested variables of age, sex, and recent substance use frequency, the sample was heterogeneous for other substance use and/or mental health history and problems, which may have influenced the findings. Overall, the sample size precluded a cross-sectional assessment of developmental changes in these networks or in DD. It was also unable to control exposure to specific substances in specific quantities. This study tested individual differences among substance users entering treatment. It will be important in future studies to assess the generalizability of these networks to teens who do not use substances, teens with substance use problems but not seeking treatment, and similar samples of adults. There are also differing methods and fMRI task parameters that have been used to study DD which may contribute to differences in activation across studies. For example, ensuring comparability in decision difficulty across subjects and balancing frequency of SS and LL choices may maximize relations between behavioral measures and neural activity42, but may minimize differences in neural activity for SS vs. LL.

Delay discounting is related to many forms of substance abuse, and it may be an informative marker of individual differences that could predict treatment response and/or improve as a result of treatment. Two neural processing networks were found to relate to individual differences in DD rates. These bottom up (e.g., limbic and paralimbic) and top down (e.g., parietal and prefrontal) networks functioned in opposition while subjects made temporal decisions about rewards. Developmental differences in the maturation of these networks may make teens both more vulnerable to impulsive decision making and substance use and more responsive to interventions targeting these systems. Neuroeconomic approaches can contribute to the understanding of neural mechanisms that underlie DD behavior, and thereby may offer additional clues to better direct prevention or treatment approaches. These results showing discounting-related differences in neural activation are consistent with competing neurobehavioral decision systems theory. Interventions to modify DD and its underlying neural mechanisms including those targeting working memory might lead to enhanced treatment outcome among adolescent substance users.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grants DA029442, DA015186, and DA022981, and by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grant AA016917.

Footnotes

Supplemental material cited in this article is available online.

Disclosure: Dr. Stanger has received support from National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Sturgis Foundation. Dr. Budney has received support from NIH. Dr. Kilts has received support from NIH and has attended a scientific advisory board meeting for Allergan and a National Advisory Board meeting for a mental health facility (Skyland Trail). He is a co-holder of US Patent No. 6,373,990 (“Method and device for the transdermal delivery of lithium”). Drs. Elton, James and Ryan report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Catherine Stanger, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

Dr. Amanda Elton, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Dr. Stacy R. Ryan, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

Dr. G. Andrew James, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Dr. Alan J. Budney, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

Dr. Clinton D. Kilts, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

References

- 1.Bickel WK, Miller ML, Yi R, Kowal BP, Lindquist DM, Pitcock JA. Behavioral and neuroeconomics of drug addiction: Competing neural systems and temporal discounting processes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 Sep;90:S85–S91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Commons ML, Mazar JE, Nevin JA, Rachlin H, editors. Quantitative analysis of behavior: The effect of delay and of intervening events on reinforcement value. Vol. 5. Hillside, NJ: 1987. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Field M, Christiansen P, Cole J, Goudie A. Delay discounting and the alcohol stroop in heavy drinking adolescents. Addiction. 2007 Apr;102(4):579–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Epstein LH, Goldman P, Wileyto EP. Applying a behavioral economic framework to understanding adolescent smoking. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004 Mar;18(1):64–73. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon JH, Higgins ST, Heil SH, Sugarbaker RJ, Thomas CS, Badger GJ. Delay discounting predicts postpartum relapse to cigarette smoking among pregnant women. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007 Apr;15(2):176–186. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Washio Y, Higgins ST, Heil SH, et al. Delay discounting is associated with treatment response among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011 Jun;19(3):243–248. doi: 10.1037/a0023617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnan-Sarin S, Reynolds B, Duhig AM, et al. Behavioral impulsivity predicts treatment outcome in a smoking cessation program for adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 Apr 17;88(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanger C, Ryan S, Fu H, et al. Delay discounting predicts treatment outcome among adolescent substance abusers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20:205–212. doi: 10.1037/a0026543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter R, Meyer J, Huettel S. Functional neuroimaging of intertemporal choice models: A review. J Neurosci Psychol Econ. 2010;3(1):27–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters J, Buchel C. The neural mechanisms of inter-temporal decision-making: Understanding variability. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011 May;15(5):227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blakemore SJ, Choudhury S. Development of the adolescent brain: Implications for executive function and social cognition. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006 Mar-Apr;47(3–4):296–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci. 1999 Oct;2(10):861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 May;101(21):8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green L, Fry AF, Myerson J. Discounting of delayed rewards: A life-span comparison. Psychol Sci. 1994;5(1):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinberg L, Graham S, O’Brien L, Woolard J, Cauffman E, Banich M. Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Dev. 2009 Jan-Feb;80(1):28–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casey BJ, Jones RM, Somerville LH. Braking and accelerating of the adolescent brain. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21(1):21–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christakou A, Brammer M, Rubia K. Maturation of limbic corticostriatal activation and connectivity associated with developmental changes in temporal discounting. Neuroimage. 2011 Jan;54(2):1344–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olson EA, Collins PF, Hooper CJ, Muetzel R, Lim KO, Luciana M. White matter integrity predicts delay discounting behavior in 9-to 23-year-olds: A diffusion tensor imaging study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009 Jul;21(7):1406–1421. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdullaev Y, Posner MI, Nunnally R, Dishion TJ. Functional MRI evidence for inefficient attentional control in adolescent chronic cannabis abuse. Behav Brain Res. 2010 Dec;215(1):45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez-Larson MPL-LMP, Bogorodzki P, Rogowska J, et al. Altered prefrontal and insular cortical thickness in adolescent marijuana users. Behav Brain Res. 2011 Jun;220(1):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tapert SF, Granholm E, Leedy NG, Brown SA. Substance use and withdrawal: Neuropsychological functioning over 8 years in youth. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002 Nov;8(7):873–883. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702870011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubinstein ML, Luks TL, Moscicki AB, Dryden W, Rait MA, Simpson GV. Smoking-related cue-induced brain activation in adolescent light smokers. J Adolesc Health. 2011 Jan;48(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudziak JJ, Copeland W, Stanger C, Wadsworth M. Screening for DSM-IV externalizing disorders with the Child Behavior Checklist: A receiver-operating characteristic analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004 Oct;45(7):1299–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Human Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;14(3):140–151. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MATLAB [computer program]. Version 6.5.1. Natick, Massachusetts: The Mathworks Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frackowiak RSJ, Friston KJ, Frith CD, Dolan RJ, Mazziotta JC, editors. Human Brain Function. Academic Press; USA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zink CF, Pagnoni G, Martin-Skurski ME, Chappelow JC, Berns GS. Human striatal responses to monetary reward depend on saliency. Neuron. 2004 May 13;42(3):509–517. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benoit RG, Gilbert SJ, Burgess PW. A neural mechanism mediating the impact of episodic prospection on farsighted decisions. J Neurosci. May. 2011;31(18):6771–6779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6559-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridderinkhof K, van den Wildenberg W, Segalowitz S, Carter C. Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: The role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward based learning. Brain Cogn. 2004 Nov 2004;56(2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hare TA, Camerer CF, Rangel A. Self-control in decision-making involves modulation of the vmPFC valuation system. Science. 2009 May;324(5927):646–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1168450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galvan A, Hare T, Voss H, Glover G, Casey BJ. Risk-taking and the adolescent brain: Who is at risk? Dev Sci. Mar. 2007;10(2):F8–F14. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Leijenhorst L, Moor BG, Op de Macks ZA, Rombouts SARB, Westenberg PM, Crone EA. Adolescent risky decision-making: Neurocognitive development of reward and control regions. Neuroimage. 2010;51(1):345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: A neurocognitive perspective. Nat Neurosci. 2005 Nov;8(11):1458–1463. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClure SM, Laibson DI, Loewenstein G, Cohen JD. Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Science. 2004 Oct 15;306(5695):503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.1100907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monterosso JR, Luo S. An argument against dual valuation system competition: Cognitive capacities supporting future orientation mediate rather than compete with visceral motivations. J Neurosci Psychol Econ. 2010;3(1):1–14. doi: 10.1037/a0016827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung T, Geier C, Luna B, et al. Enhancing response inhibition by incentive: Comparison of adolescents with and without substance use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011 May;115(1–2):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jazbec S, Hardin M, Schroth E, McClure E, Pine D, Ernst M. Age-related influence of contingencies on a saccade task. Exp Brain Res. 2006;174(4):754–762. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0520-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shamosh NA, DeYoung CG, Green AE, et al. Individual differences in delay discounting relation to intelligence, working memory, and anterior prefrontal cortex. Psychol Sci. 2008 Sep;19(9):904–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bickel WK, Yi R, Landes RD, Hill PF, Baxter C. Remember the future: Working memory training decreases delay discounting among stimulant addicts. Biol Psychiatry. 2011 Feb;69(3):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Houben K, Wiers RW, Jansen A. Getting a grip on drinking behavior: Training working memory to reduce alcohol abuse. Psychol Sci. 2011 Jul;22(7):968–975. doi: 10.1177/0956797611412392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monterosso JR, Ainslie G, Xu JS, Cordova X, Domier CP, London ED. Frontoparietal cortical activity of methamphetamine-dependent and comparison subjects performing a delay discounting task. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007 May;28(5):383–393. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.