Abstract

A new device and method to measure rabbit knee joint angles are described. The method was used to measure rabbit knee joint angles in normal specimens and in knee joints with obvious contractures. The custom-designed and manufactured gripping device has two clamps. The femoral clamp sits on a pinion gear that is driven by a rack attached to a materials testing system. A 100 N load cell in series with the rack gives force feedback. The tibial clamp is attached to a rotatory potentiometer. The system allows the knee joint multiple degrees-of-freedom (DOF). There are two independent DOF (compression-distraction and internal-external rotation) and two coupled motions (medial-lateral translation coupled with varus-valgus rotation; anterior-posterior translation coupled with flexion-extension rotation). Knee joint extension-flexion motion is measured, which is a combination of the materials testing system displacement (converted to degrees of motion) and the potentiometer values (calibrated to degrees). Internal frictional forces were determined to be at maximum 2% of measured loading. Two separate experiments were performed to evaluate rabbit knees. First, normal right and left pairs of knees from four New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits were subjected to cyclic loading. An extension torque of 0.2 Nm was applied to each knee. The average change in knee joint extension from the first to the fifth cycle was 1.9 deg ± 1.5 deg (mean ± sd) with a total of 49 tests of these eight knees. The maximum extension of the four left knees (tested 23 times) was 14.6 deg ± 7.1 deg, and of the four right knees (tested 26 times) was 12.0 deg ± 10.9 deg. There was no significant difference in the maximum extension between normal left and right knees. In the second experiment, nine skeletally mature NZW rabbits had stable fractures of the femoral condyles of the right knee that were immobilized for five, six or 10 weeks. The left knee served as an unoperated control. Loss of knee joint extension (flexion contracture) was demonstrated for the experimental knees using the new methodology where the maximum extension was 35 deg ± 9 deg, compared to the unoperated knee maximum extension of 11 deg ± 7 deg, 10 or 12 weeks after the immobilization was discontinued. The custom gripping device coupled to a materials testing machine will serve as a measurement test for future studies characterizing a rabbit knee model of post-traumatic joint contractures.

Introduction

Injury to a human joint leads to a risk of motion loss in that joint. It has been estimated that there is complete loss of motion following 5% of elbow injuries [1]. Permanent loss of motion (contracture) can affect joint function. For example, an inability to flex the elbow completely makes it difficult to position the hand about the neck and face. Similarly, an inability to straighten the knee completely limits running capability. An anatomic basis for the development of joint contracture is well recognized [1]. Intrinsic joint factors (surface incongruity, joint capsule/ligaments, peri-articular osteophytes) and extrinsic joint factors (muscle-tendon units, skin contractures) contribute to joint contracture in varying degrees [1]. Operative intervention to improve human elbow joint motion focuses on division or excision of the joint capsule [2–5]. Despite a sound anatomic basis for the development of joint contracture, there is little understanding of what changes in the joint capsule in the first place. Our research group is developing an animal model of post-traumatic joint contracture with the goal of investigating the underlying changes in the joint capsule.

Several authors have studied joint contractures using animal models [6–12]. Most have immobilized otherwise normal joints, which has limitations when considering the issue of post-traumatic joint contractures [6,12,13]. First, the effect of the injury on the contracture process is not modelled. Second, and most important, while immobilization of a normal rabbit knee joint leads to joint contracture when the joint is immobilized, these joint contractures are reversible if the immobilization is stopped [7]. This reversibility does not model the human scenario of permanent contracture following injury. There have been models of peri-articular injury with joint immobilization that do lead to joint contractures, but the permanency of the joint contractures has not been reported once the immobilization was discontinued [8–11]. In the development of our animal model of post-traumatic contractures, the ultimate goal is to describe the natural history of the joint contractures to determine whether permanent joint contractures develop and remain even after discontinuing the immobilization. A prerequisite to describe this model is a standardized method to measure joint angles.

Only a few authors have reported methods for systematic biomechanical measurement of joint contractures in animal models [6,8,9,12,14,15]. Trudel et al., used a rat knee and had a 1-degree-of-freedom (DOF) device [12]. Fukui et al., made knee measurements on a live anaesthetised rabbit [8,9]. They used a relatively simple method of a wire looped around the leg to apply a torque and used plain radiographs to measure the joint angles. Limitations of this method include difficulty in consistently placing the wire a standard distance from axis of rotation (without slippage of the wire on the leg), variable compression of the calf soft-tissue by the wire, the requirement to move the pulley used to suspend the weight manually as the knee moved, and the level of anaesthesia of the rabbits [8,9]. Woo et al., designed a device to measure knee joint angles [15]. They used it originally on live animals, but later used it on isolated lower extremity specimens due to testing difficulties on live anaesthetised rabbits [7]. The device measured joint stiffness and the energy required for flexion-extension joint motion. The device was not used to measure maximum joint extension (which is the clinical measure of joint contracture) and the DOF were not mentioned [15]. Akai et al., measured rat knees using a plastic goniometer with the femur clamped and the tibia free to extend with gravity [6,14]. Maximum knee extension was not measured with their system, rather they reported joint stiffness using fast Fourier transform testing of joint vibrations.

The equipment mentioned in the previous paragraph was custom made: commercial apparati are not available. Thus, we designed and manufactured our own device modifying and selecting certain attributes of the other apparati reviewed [6,8,9,12,14,15]. Our methodology incorporates a custom gripping device attached to a materials testing system. The custom gripping device clamps the femur and tibia of the rabbit knee. The device incorporates multiple-DOF, including two sets of coupled motions, that allows motion through the three translations and the three rotations about the joint. This clamping device interacts with a materials testing system through a rack and pinion arrangement, allowing the application of a standard torque to measure maximum knee joint extension. Ionizing radiation exposure, with its attendant long-term health risk to research personnel, is avoided with this methodology. Consistent gripping of the limbs and consistent application of a torque are assured in this device. Finally, maximum joint extension is measured to correspond to the clinical measure used to define joint contractures.

The apparatus is described together with the standardized rabbit knee joint angle measurement methodology. The methodology was then used on rabbit knees with and without joint contracture. Our objectives were: 1) to cycle rabbit knees repetitively to evaluate preconditioning effects; 2) to compare normal left and right knee joint angle measures; 3) to determine whether obvious post-traumatic joint contractures could be detected in a new rabbit knee model of such contractures using gross estimations under general anaesthesia or immediately at sacrifice, and 4) to determine whether post-traumatic rabbit knee joint contractures in the new rabbit knee model could be measured using our standardized in vitro measurement system.

Methods and Materials

Device Description and Joint Angle Measurement

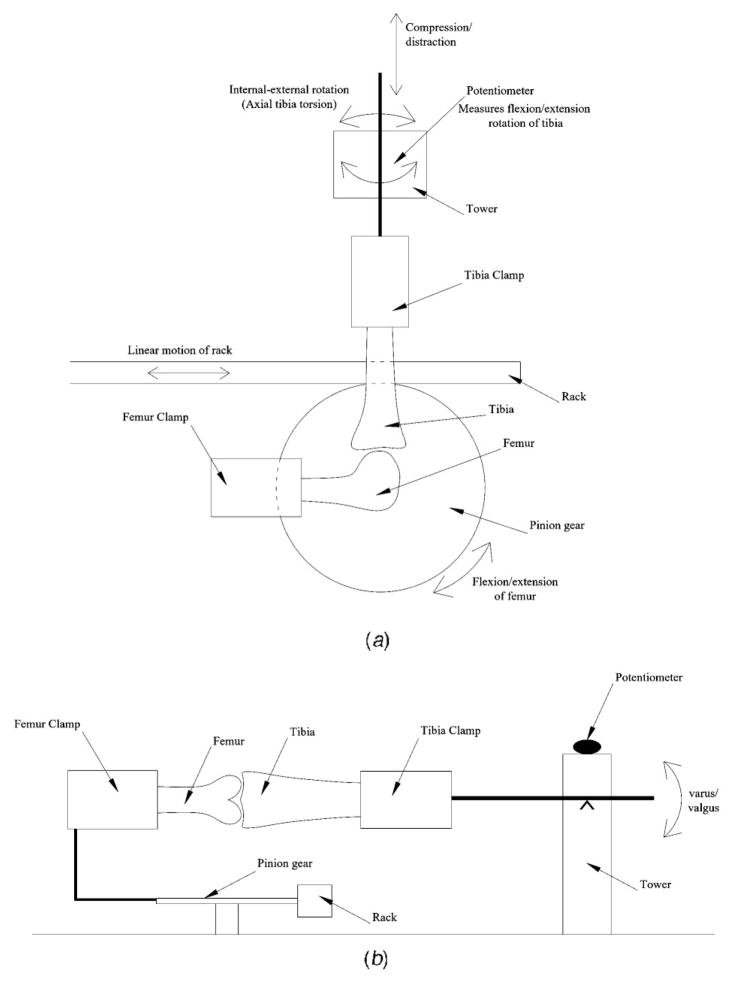

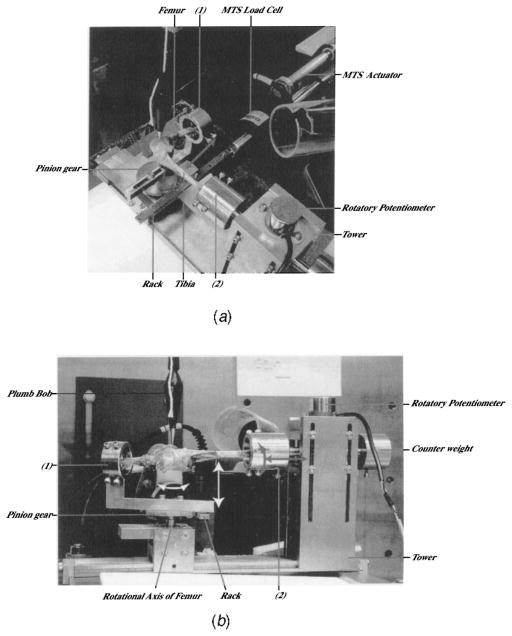

The custom-designed and manufactured device has clamps to grip the bones (tibia, femur) of the knee joint (Figs. 1 and 2). The femur is gripped in a bone clamp that is rigidly attached to a pinion gear. The pinion gear has a 63.5 mm (2.5″) pitch diameter. This fixture is supported by two instrument grade stainless steel ball bearings. The pinion gear is rotated by linear motion of the accompanying rack, induced by a linear hydraulic actuator (MTS, Eden Prairie, MN). The MTS actuator is controlled by MTS TestStar II software, providing motion control and load measurement. The knee joint is positioned such that displacement of the actuator creates a flexion-extension moment at the knee (Fig. 1a). A 100 N load cell (MTS) is placed in series with the rack to detect force in the system. The tibia is gripped in the other bone clamp attached to a tower (Figs. 1 and 2). The tibia bone clamp is free to rotate in all directions (flexion-extension, varus-valgus, and internal-external) and translate in compression-distraction (Fig. 1a and b). A counter weight balances the tibial clamp (Fig. 2b). While the femur is forced to follow a specific flexion-extension path of motion through the rack and pinion arrangement, the tibia can rotate and translate freely (Fig. 1a and b). The arrangements and freedoms of the femur and tibia clamps accommodate multiple-DOF of the knee joint, with two sets of coupled motions and two sets of independent motions. Thus, as the joint flexes/extends through the imposed in vitro range of motion, anterior-posterior translation is coupled with flexion-extension rotation (Fig. 2a), while medial-lateral translation is coupled with varus-valgus rotation (Fig. 2b). Compression-distraction and internal-external rotation are independent DOF (Fig. 2b). Knee joint flexion-extension values are a combination of the MTS actuator displacement converted to degrees and tibial flexion-extension rotation measured with the rotatory potentiometer on top of the tower (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

(a) Sagittal schematic. The femur clamp is rigidly attached to the pinion gear. The tibia clamp is free to rotate in the sagittal plane (flexion-extension ) and along its axis (internal-external rotation), and to translate longitudinally (compression-distraction).(b) Coronal schematic. The tibia clamp is free to rotate in the coronal plane (varus-valgus).

Fig. 2.

(a) Adult female rabbit right knee specimen mounted for testing. (1) Femur clamp. (2) Tibia clamp. Coupled knee extension-flexion rotation and anterior-posterior translation are shown (grey arrows). (b) A demonstration of varus-valgus rotation coupled with medial-lateral translation (white arrows) and the independent degrees-of-freedom knee compression-distraction and internal-external rotation (grey arrows). (1) Femur clamp. (2) Tibia clamp.

The custom device is constructed from stainless steel. Three sets of two screws each allow secure gripping of the femur and tibia in their respective clamps (Fig. 2). Accuracy of the flexion/ extension moment was determined for the custom-designed and fabricated device itself by using the manufacturer’s stated linear load cell accuracy and one-half the pitch diameter. Accuracy is calculated to be ± 0.003 Nm. Frictional loads internal to the custom device are determined to be, at most, 2% of the measured load when the device is moved by the MTS with no specimen mounted.

Maximum knee joint extension is measured as the posterior soft-tissue knee joint structures are the source of contracture in the animal model to be described. To ensure consistent mounting of the knees, the femur clamp on the pinion is placed at 90 deg to the tower housing the second clamp (tibia). Consistent position of the knee joint relative to the pinion axis of rotation is ensured by placing the femoral epicondyles, located just superior to the collateral ligament insertions, over the pinion axis. The medial collateral ligament faces up. While the true axis of rotation of a rabbit knee is not known, the human knee axis of rotation is the femoral epicondyles [16]. A plumb bob is suspended above the center of the pinion to aid in positioning the knee axis of rotation over the pinion axis of rotation (Fig. 2). Quasi-static testing (0.4 mm/s) is used to minimize inertial effects while self-weight of the system is neglected due to flexion-extension measurements taking place perpendicular to gravity. Testing begins with the knee joint at 90 deg of flexion. An extension torque is applied to a maximum of 0.2 Nm or to a maximum of 55 mm displacement of the MTS actuator. The maximum torque is calculated based on in vivo loading of the intact rabbit hind limbs [8,9]. Fukui et al. used 0.49 Nm on anaesthetised rabbits and intact lower limbs. We use 0.2 Nm for our in vitro model of an isolated lower extremity with the thigh and leg muscles largely resected. The soft-tissues are kept moist with intermittent irrigation of normal saline solution. Extension is recorded as a number between 0 deg and 90 deg, with values near 0 deg representing maximum extension. Negative numbers are termed hyperextension. Thus, a larger maximum extension angle actually represents a more severe contracture, or loss of motion, as normally extension is closer to 0 deg.

Animal Experiments

Two experiments were performed to investigate the four objectives. Female New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits were obtained from Reimans Furrier, St. Agatha, ON in both experiments. Institutional Animal Review Committee approval was obtained prior to the animal experiments. First, the knees of four rabbits (9–12 months old, 4.5 ± 0.7 kg) were used to assess preconditioning, and left versus right measures (Objectives 1 and 2). No operative interventions were performed on these rabbits. In the second experiment (Objectives 3 and 4), nine rabbits (12–15 months old, 5.7 ± 0.5 kg) were used. Under general anaesthesia, incisions over the lateral thigh and anterior aspect of the mid-tibia of the right hind limb were made. The lateral thigh incision allowed access to the knee joint. Medial and lateral para-patellar arthrotomies were made and 5-mm2-cortical windows were removed from the non-articular cartilage portion of the medial and lateral femoral condyles using an osteotome. Bleeding from the condyles represented an intra-articular fracture. Care was taken not to detach the collateral ligaments. The arthrotomies were not closed.

The knee joint was then immobilized with a 1.6-mm-diameter Kirschner wire (Zimmer, Mississauga, ON) [13,17]. The lateral thigh incision was used to expose the femur. The tibial incision allowed the drilling of the Kirschner wire (K-wire) through the tibia; the K-wire was passed posterior (extra-articular) to the knee joint and bent around the femur with the knee at 150 deg of flexion. This method has been used by several authors without report of damage to posterior vessels or nerves [7,13,17,18]. All skin incisions were closed with 3-0 Ethilon (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Peterborough, ON). The rabbits were allowed free cage activity (0.1 m3) following the operation. The left knees served as an unoperated control.

The knees were immobilized five, six or 10 weeks at which time the K-wires were cut under general anaesthesia and the tibial portion of the K-wires were removed (Table 1). Different times were selected to see if obvious differences in the severity of joint contractures could be detected at the time of K-wire removal. Another general anaesthetic was given five or six weeks after K-wire removal to determine whether joint contractures were still present. The rabbits were then sacrificed 10 or 12 weeks after the K-wires were removed (Table 1). These remobilization times represented 1 or 2× greater intervals than the immobilization times. Whole knee joint angle measurements were estimated at K-wire removal, five or six weeks after K-wire removal, and at sacrifice (Objective 3). This was performed with the rabbit supine. The foot was grasped and lifted toward the ceiling, extending the knee until the pelvis was elevated from the table. Hip and ankle motion was not constrained. The knee joint angle was estimated with a hand held goniometer such that one arm followed the mid portion of the thigh, and the second arm followed the tibia. The axis of the goniometer was aligned on the lateral side of the femoral condyles.

Table 1.

Allocation of rabbits for objectives 3 and 4

| IMMOBILIZATION | REMOBILIZATION | NUMBER OF RABBITS |

|---|---|---|

| 5 weeks | 10 weeks | 3 |

| 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 3 |

| 10 weeks | 10 weeks | 3 |

After sacrifice, the hind limbs were disarticulated at the hips and ankles, and stored at −80 degC. For biomechanical tests, the limbs were thawed overnight to room temperature. The muscle, tendons and skin were removed from the femur and tibia. All tissue (except the skin) from the superior border of the patella to 1 cm distal to the patellar tendon insertion on the tibia was left intact to protect the joint capsule (Fig. 2). One control knee specimen was damaged in preparation for biomechanics and was excluded (Objective 4).

For Objectives 1 and 2, the 8 normal knees underwent a total of 49 tests. Each knee was tested on 2–3 separate days over 2–3 months. The knees were stored frozen at 80 degC between test days. Tests (of five consecutive cycles) on the same day had at least 10 minutes rest between the end of one test and the start of the second test. Maximum extension angles were measured. Knee extension values of the individual cycles, average of the five cycles and difference between first and fifth cycles were calculated to evaluate preconditioning (Objective 1). Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine if any differences existed between the various cycles for Objective 1 with paired t-tests to detect differences between each cycle group mean for posthoc analysis. Left versus right comparisons were made using first cycle, fifth cycle and the average of the five cycles (Objective 2). The experiments using rabbits with post-traumatic knee contractures (Objectives 3 and 4) had a single test of one extension-flexion cycle. A paired t-test was used for the left versus right comparisons of Objective 2 and the experimental versus control knees of Objective 4. Significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

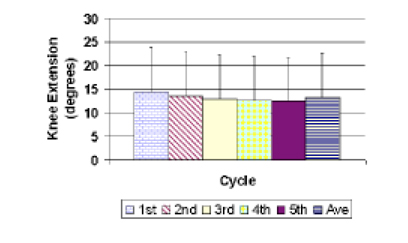

In the first experiment, preconditioning in normal knees was evaluated by considering the change in maximum extension in relation to the cycle number (Objective 1, Fig. 3). Forty-nine separate tests of the 8 knees spread over several days during 2–3 months determined that the average difference between the maximum extension angle obtained in first and fifth loading cycles was 1.9 deg ± 1.5 deg. The difference between successive cycles became smaller (Fig. 3). There was a significant difference on repeated measures ANOVA and posthoc analysis determined that the only significant difference between individual cycles occurred when comparing the average of the first cycle and the average of the fifth cycle (p<0.05). The average maximum extension on the first cycle was 14.4 deg ± 9.5 deg while the average maximum extension on the fifth cycle was 12.5 deg ± 9.2 deg (Fig. 3). Averaging cycles one to five showed that maximum extension was 13.2 deg ± 9.3 deg (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Preconditioning

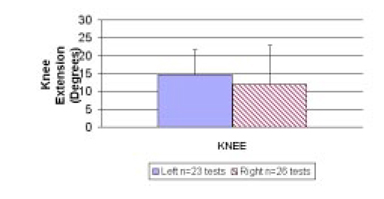

For left versus right comparisons (Objective 2), there were no significant differences in the maximum knee joint extension group means, whether the first cycle, fifth cycle or an average of the five cycles was used for comparison (p>0.05). There were 23 separate tests of the four left knees and 26 separate tests of the four right knees. The maximum extension values using the average of the five cycles are shown in Fig. 4. The maximum extension of left knees measured 14.6 deg ± 7.1 deg and maximum extension of right knees measured 12.0 deg ± 10.9 deg using the average of 5 cycles.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of normal right and left knee extension (Objective 2). Average of five cycles

The serial estimates of the knee joint contractures in the animal model showed that obvious contractures developed in the experimental knee (Objective 3). The whole limb knee joint maximum extensions for the injured/immobilized knees were estimated between 90 deg–100 deg at pin removal, approximately 45 deg five or six weeks after pin removal and remained around 45 deg at the time of sacrifice. There were no obvious differences in the maximum extension based on the length of immobilization. The estimated maximum knee joint extension of the contralateral knees was 0 deg at all times. Thus, there appeared to be obvious post-traumatic joint contractures to measure with the custom gripping device/MTS method 10 or 12 weeks following K-wire removal.

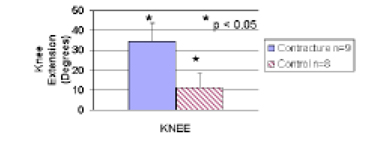

Significant differences between the experimental (right) knees and the control (left) knees (p<0.05, Fig. 5) were found using the new method described to measure rabbit knee joint angles (objective 4). The average measured maximum extension of the experimental knees was 35 deg ± 9 deg while the control knees averaged 11 deg ± 7 deg, 10 or 12 weeks after the immobilized knee had been remobilized. Thus, the experimental knee had a larger number which reflects a greater lack of extension, representing a post-traumatic joint contracture.

Fig. 5.

Experimental (Contracture) versus unoperated (Control) knees (Objective 4)

Discussion

The new method of rabbit knee joint angle measurement incorporates a custom-designed and manufactured gripping device that clamps the bones (femur and tibia), allows multiple-DOF, and uses a rack and pinion device to convert linear displacement of a materials testing machine actuator into flexion-extension rotation. Flexion-extension rotation is a combination of the displacement of the actuator and the flexion-extension rotation as measured on the potentiometer of the tower clamp holding the tibia (Figs. 1 and 2). The rabbit knee model of post-traumatic contracture consisted of a stable, intra-articular fracture, combined with immobilization of the joint, to produce the contracture. The immobilization was discontinued and measurements of knee joint flexion contractures were made 10 or 12 weeks after the knees were remobilized, using the new method.

The measures of joint angle with cycling using the custom device and MTS showed changes in the maximum extension achieved with each cycle such that there was more extension (joint angle value closer to 0 deg) with each cycle (Objective 1, Fig. 3). The differences between successive cycles became smaller (Fig. 3). These observations suggest that the soft tissues were stretching with each repeated loading, consistent with cyclic loads of ligaments [19]. There was a statistically significant difference between the first and fifth cycles (p<0.05). The average differences between the first and fifth cycle in the normal legs (1.9 deg ± 1.5 deg) represent about 10%–15% of the average maximum extension joint angles of normal right and left knees of the rabbits used for Objectives 1 and 2 and control left knees from the rabbits used in Objective 4. Normal left versus right knee comparisons showed no statistically significant differences. This was true whether the comparison used the first cycle, the fifth cycle, or an average of the five cycles as shown in Fig. 4. Thus, while cycling or preconditioning does have an effect on joint angle measures, comparisons between different groups of knees can be made as long as the same cycle (or average) is used.

The normal rabbit knee does not extend to 0 deg as does the human knee since the maximum extension values were between 11 deg and 14 deg short of “full” extension in our study. This has been observed by other authors [8,9]. Several factors may contribute to this “lack of full extension.” First, the rabbit knee is held in a predominantly flexed position (>90 deg). This predominantly flexed position could lead to adaptation in bone shape around the knee joint, which prevents full extension. Previous work by Walsh et al., at our research center studied the effects of immobilization on ligament development in immature rabbit knees [17]. The knees were immobilized in flexion, and with continued growth the shapes of the femur and tibia were distorted affecting joint extension. Alternatively, a predominantly flexed position may predispose the posterior soft-tissues (joint capsule, tendons, muscles) to be relatively shorter than in other species, and hence to become taut before 0 deg extension. A second factor unrelated to rabbit knee joint anatomy that may contribute to the observed normal rabbit knee extension is the torque used to extend the knee. We selected a torque that will “easily” extend the normal rabbit knee maximally without damaging posterior soft-tissue structures. Using this same torque on knees with “contractures” should demonstrate the contracture without irreparably damaging the posterior soft-tissues for subsequent histological and biochemical analyses in future studies. The goal was to develop a standard torque to detect differences between “normal” knees and knees with contractures, not to find a torque that may extend the normal knee to 0 deg.

Another goal was to measure joint angles in knees subjected to different interventions. The experimental knees had a stable intra-articular fracture in association with immobilization for five, six or 10 weeks. The knees were then remobilized for 10 or 12 weeks or 1-2× longer than the joint were immobilized. Examination of intact whole knee joints showed obvious loss of extension (i.e., flexion contractures) at the time of K-wire removal, five or six weeks after K-wire removal and at sacrifice when compared to the contralateral knees that were neither injured nor immobilized (Objective 3). There was no obvious difference in the degree of joint contracture between the three different combinations of immobilization and remobilization at any of the time periods observed. An encouraging observation was that the contracture severity initially decreased but seemed to stabilize with the later time periods. This observation is in contrast to the model of normal rabbit knees being immobilized for nine weeks, then remobilized for nine weeks where the joint contractures were resolved within the 1st time period of remobilization [7]. Further study is required on the natural history of post-traumatic joint contractures over time with a more rigorous system such as the custom gripping device/MTS methodology reported here. While not the focus of the current study, future work will investigate the role of immobilization alone in the contracture development.

The knees of the rabbits in these studies (obvious right knee post-traumatic contractures and uninjured left knees, Objective 3) were used to determine whether the custom gripping device/MTS methodology could detect the joint contractures (Objective 4). Under conditions of a 0.2 Nm torque, the system detected a significant difference in the knee joint angles between these two groups of knees. The absolute difference in group means was approximately 24 deg (Fig. 5). Thus, the developed methodology could detect post-traumatic rabbit knee joint contractures, even with remobilization of the limbs. Statistically significant differences in contracture severity could not be detected between the three groups of immobilization/remobilization (Table 1) with this new method described to measure rabbit knee joint contractures. The small numbers in each group (n = 3) limit the power to determine if small but significant differences do exist between the groups.

There was discrepancy in the absolute values assigned to knee joint extension when estimating with intact whole joints and goniometers manually or dissected hind limbs and the new methodology. With whole intact limbs, the experimental knees were estimated to have 45 deg maximum extension at sacrifice (Objective 3), while the measure of the dissected limb using the custom device/MTS was 35 deg ± 9 deg (Objective 4). The control intact whole limb maximum free extension was estimated to be 0 deg while the measure of the dissected limb was 11 deg ± 7 deg. Several factors may contribute to these discrepancies. There were limitations with the whole limb estimates. The most likely source of error in the whole limb estimates is the consistent locating of surface land marks. The rabbit thigh is relatively short and is covered by a relatively thick muscle mass when compared to the human thigh. This makes it difficult to define the femur. The rabbit femoral condyles are smaller than human femoral condyles making it difficult to locate the epicondyles by palpation for placing the goniometer axis of rotation. The rabbit tibia is easier to define from surface landmarks. Most other authors have not reported the use of goniometers in manual measurements preferring instead methods using plain radiographs or mechanical linkages that gripped the bones directly while measuring joint angles with potentiometers [7–9,11–13,15]. The implication for these authors is that the methods they chose were more accurate than manual measures made with goniometers with surface landmarks. The discrepancies between the manual whole joint goniometer measures and the measures of the new methodology described in our study support the implied improved accuracy of the more sophisticated measures described by these authors.

Other sources of error when comparing the two methods of joint contracture measurement in our study pertain to the degree of muscle stiffness (dynamic contraction), and static connective tissue shortening/fibrosis within the muscle of the whole limbs. The muscle-tendon units were completely intact in the whole limbs but not in the dissected limbs. Factors such as level of anaesthesia and consequent dynamic control of the joints or fibrosis in certain parts of the muscle may not have been equal in the two groups. While a direct comparison of the absolute values of these two measurement methods is not appropriate, the evaluation of the whole joint contractures under anaesthesia or at the time of sacrifice does provide a reality check confirming the presence of contractures detected with the new methodology we have described. This estimation of joint contractures manually with goniometers has been useful in developing our animal model of contractures as we have determined that obvious joint contractures do not develop when the injury alone was made (preliminary work, data not shown).

In conclusion, we have designed and manufactured a multiple-DOF custom gripping device that is coupled to a materials testing system to measure rabbit knee joint extension angles using a standardized torque. Measurements are made without the use of ionizing radiation. This methodology simulates the clinical measure of joint angles where the patient actively moves the joint to its motion limit. The clinical test of joint motion is not a load to failure test; thus, the in vitro measure of joint motion is not a load to failure test. The new methodology we have described to measure rabbit knee joint angles has successfully measured joint contractures in a newly developed animal model of posttraumatic joint contractures in this study. This new device and methodology will be used for future studies to measure severity of joint contractures as we further characterize the natural history of the post-traumatic joint contractures in this new animal model.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carla Gronau for preparing the manuscript and Mei Zhang, Kent Paulson and Craig Sutherland for technical support. This work was funded by grants from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, the Canadian Orthopaedic Foundation and the University of Calgary. Michael Holmberg received support from the National Science and Engineering Research Council.

Contributor Information

Kevin A. Hildebrand, Department of Surgery, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB Canada T2N 4N1.

Michael Holmberg, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB Canada T2N 4N1.

Nigel Shrive, Department of Surgery and Department of Civil Engineering, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB Canada T2N 4N1.

References

- 1.Cooney WP., III . Contractures of the elbow. In: Morrey BF, editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 2. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1993. pp. 464–475. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Hastings IH. Post-Traumatic Contracture of the Elbow. J Bone Jt Surg. 1998;80-B:805–812. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b5.8528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mansat P, Morrey BF. The Column Procedure: A Limited Lateral Approach for Extrinsic Contracture of the Elbow. J Bone Jt Surg, Am Vol. 1998;80-A:1603–1615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timmerman L, Andrews J. Arthroscopic Treatment of Posttraumatic Elbow Pain and Stiffness. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:230–235. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urbaniak JR, Hansen PE, Beissinger SF, Aitken MS. Correction of Post-Traumatic Flexion Contracture of the Elbow by Anterior Capsulotomy. J Bone Jt Surg, Am. 1985;67-A:1160–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akai M, Shirasaki Y, Tateishi T. Viscoelastic Properties of Stiff Joints: A New Approach in Analyzing Joint Contracture. Biomed Mater Eng. 1993;3:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akeson W, Woo SLY, Amiel D, Doty D. Rapid Recovery from Contracture in Rabbit Hindlimb: a Correlative Biomechanical and Biochemical Study. Clin Orthop. 1977;122:359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukui N, Nakajima K, Tashiro T, Oda H, Nakamura K. Neutralization of Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 Reduces Intra-articular Adhesions. Clin Orthop. 2001;383:250–258. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200102000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukui N, Tashiro T, Hiraoka H, Nakamura K. Adhesion Formation Can Be Reduced by the Suppression of Transforming Growth Factor-Beta 1 Activity. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:212–219. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meals RA. An Improved Rabbit Restraint for Chronic Hind Limb Studies. Clin Orthop. 1985;192:275–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Namba R, Kabo M, Dorey F, Meals R. Intra-Articular Corticosteroid Reduces Joint Stiffness After an Experimental Periarticular Fracture. J Hand Surg [Am] 1992;17A:1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(09)91083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trudel G, Uhthoff H. Contractures Secondary to Immobility: Is the Restriction Articular or Muscular? An Experimental Longitudinal Study in the Rat Knee. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:6–13. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(00)90213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akeson W, Amiel D, Woo SLY. Immobility Effects on Synovial Joints the Pathomechanics of Joint Contracture. Biorheology. 1980;17:95–110. doi: 10.3233/bir-1980-171-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akai M, Shirasaki Y, Tateishi T. Electrical Stimulation on Joint Contracture: An Experiment in Rat Model With Direct Current. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:405–409. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo SLY, Matthews JV, Akeson W, Amiel D, Convery FR. Connective Tissue Response to Immobility. Arthritis Rheum. 1975;18:257–264. doi: 10.1002/art.1780180311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollister AM, Jatana S, Singh AK, Sullivan WW, Lupichuk AG. The Axes of Rotation of the Knee. Clin Orthop. 1993;290:259–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh S, Frank CB, Hart DA. Immobilization Alters Cell Metabolism in an Immature Ligament. Clin Orthop. 1992;277:277–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akeson W, Amiel D, Mechanic G, Woo SLY, Harwood F, Hamer M. Collagen Cross-Linking Alterations in Joint Contractures: Changes in the Reducible Cross-Links in Periarticular Connective Tissue Collagen After Nine Weeks of Immobilization. Connect Tiss Res. 1977;5:15–19. doi: 10.3109/03008207709152607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thornton GM, Oliynyk A, Frank CB, Shrive NG. Ligament Creep Cannot be Predicted From Stress Relaxation at Low Stress: A Biomechanical Study of the Rabbit Medial Collateral Ligament. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:652–656. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]