Abstract

While there is strong evidence that bisphosphonates prevent certain types of osteoporotic fractures, there are concerns that these medications may be associated with rare atypical femoral fractures (AFF). Recent published studies examining this potential association are conflicting in regards to the existence and strength of this association. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies examining the association of bisphosphonates with subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and AFF. The random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled estimates of adjusted risk ratios (RR). Subgroup analysis was performed by study design, for studies that used validated outcome definitions for AFF, and for studies reporting on duration of bisphosphonate use. Eleven studies were included in the meta-analysis: five case-control and six cohort studies. Bisphosphonate exposure was associated with an increased risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and AFF with adjusted RR of 1.70 (95% CI 1.22–2.37). Subgroup analysis of studies using the ASBMR-criteria to define AFF suggests a higher risk of AFF with bisphosphonate use with RR of 11.78 (95% CI 0.39–359.69) as compared to studies using mainly diagnosis codes (RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.18–2.22), although there is a wide confidence interval and severe heterogeneity (I2=96.15%) in this subgroup analysis. Subgroup analysis of studies examining at least 5 years of bisphosphonate use showed adjusted RR of 1.62 (95% CI 1.29–2.04). This meta-analysis suggests there is an increased risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and AFF among bisphosphonate users. Further research examining the risk of AFF with long-term use of bisphosphonates is indicated as there was limited data in this subgroup. The public health implication of this observed increase in AFF risk is not clear.

Keywords: Atypical femur fracture, bisphosphonates, osteoporosis, subtrochanteric fracture, femoral shaft fracture

Introduction

Over half of the United States population greater than age 50 has osteoporosis or low bone mass, and the prevalence is expected to grow with the aging population.(1) Medications to prevent and treat osteoporosis, such as bisphosphonates, are therefore increasingly used. Bisphosphonates prevent common osteoporotic fractures in patients with osteoporosis, particularly in the hip and vertebrae.(2) Bisphosphonates remain among the most commonly used medications for prevention of fracture in osteoporotic patients, with a recent study estimating that over 4 million women in the US greater than 45 years of age were taking bisphosphonates in 2008.(3)

While bisphosphonates prevent typical osteoporotic fractures,(2) prior studies raise concern that these agents may actually cause atypical femoral fractures (AFF). While the mechanism of this is unknown, studies suggest that bisphosphonates may negatively affect bone remodeling and lead to increased microdamage.(4, 5) Unlike typical hip fractures found in the femoral neck, trochanteric, and intertrochanteric regions of the femur, AFF occur in the subtrochanteric and femoral shaft regions. Fractures in the subtrochanteric or femoral shaft regions are rare, with some studies estimating 3 fractures per 10,000 person-years in certain populations.(6) Hip fractures are more common, with an estimated incidence of 103 fractures per 10,000 person-years.(6) However, while the incidence of hip fractures is decreasing in the US, the incidence of subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures is stable or possibly increasing.(7, 8)

One potential reason for this rise in incidence may be the growing use of bisphosphonates. Several epidemiologic studies demonstrated an increased risk of subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures with use of bisphosphonates, particularly with long-term use of these medications.(9–11) However, other observational studies and re-analysis of randomized controlled trials of bisphosphonates found no increased risk of subtrochanteric and femoral fractures or AFF, although this may due to limited statistical power.(12–14)

This study aimed to systematically review all published studies that examined the potential association of AFF with bisphosphonate use. We did not impose age, gender, or geographic limitation for included studies. We summarized this published data in a meta-analysis, to determine the risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and AFF with use of bisphosphonates, particularly with long-term use.

Methods

A full study protocol is available online, titled “Study protocol for Bisphosphonates and Risk of Atypical Femur Fracture: A Meta-analysis”. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses statement to guide our methods for this study.(15)

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE databases (January 1st, 1990 - October 19th, 2012) for studies examining the association of bisphosphonate use and AFF, as well as subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures. These dates were chosen as the initial reports of the association of AFF with bisphosphonates occurred after the 1990s. We performed the search using the following keywords and Medical Subject Headings: [“diphosphonates” (this term includes alendronate, clodronic acid, and etidronic acid) OR “bisphosphonate” OR “ibandronic acid” OR “pamidronate” OR “zoledronic acid” OR “risedronic acid”] AND [“femoral fractures” OR “femur fracture” OR “hip fractures” OR “diaphyseal AND femoral fracture” OR “atypical AND femoral fractures”] AND [“subtrochanteric” OR “diaphyseal” OR “midshaft” or “atypical”]. We included only studies published in English. We also searched available abstracts from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), American Society of Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR), and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) annual meetings from 2006–2011. If potential studies were found in abstract form, we then searched MEDLINE and EMBASE to determine whether the abstracts were published in full manuscript form. Only fully published data were used for the meta-analysis.

Study eligibility and selection

We included prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, and secondary analysis of randomized controlled trials in our review. Eligible studies compared bisphosphonate use to 1) no bisphosphonate-use, 2) placebo, or 3) a non-bisphosphonate osteoporosis medication. We used subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, or atypical femur fractures as the reported outcomes required for inclusion into the study. We allowed for heterogeneity in outcomes as the types of reports available for each potential study were variable; certain studies only had access to International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes to identify fracture, while other studies identified fractures based on imaging and could identify atypical features. Case reports, case series, studies on animal models, review articles, letters or editorials were excluded from the study. Studies examining bisphosphonate use in patients with malignancies or metabolic syndromes such as Paget’s disease were also excluded. Studies reporting only crude-estimates of association between subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, or AFF and bisphosphonate use were not included in the study, as we believed important potential confounders such as age and sex should be controlled. Two authors (LG and SCK) independently reviewed abstracts and/or full-texts to determine study eligibility using a study screening form the authors created to determine eligibility for inclusion in our analyses (see online supplementary material, eFigure 1). If there was disagreement on eligibility between the two authors this was resolved by author consensus.

Data abstraction and quality assessment

Independent data collection forms were used by two authors (LG and SCK) to extract data from each eligible study. The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was then used independently by the two authors (LG and SCK) to help determine quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis. This commonly used quality assessment scale gives points to nonrandomized studies on quality of definition of selection groups (0–4), ascertainment of exposures and outcomes (0–3 points), as well as comparability of the two populations to be studied (0–2 points).(16) The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment scale determines that a larger total number of points attributed to a study correlates with increased quality of the study. The scale can be modified a priori in order to be tailored to the proposed meta-analysis. We determined a priori that studies radiologically confirming AFF and reporting on duration of bisphosphonate treatment received increased number of points in the ascertainment of exposures and outcomes (see online supplementary material, eTable 1).

Statistical analysis

The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled estimates of adjusted risk ratios (RR) as we assumed that either odds ratio or hazard ratio was equivalent to RR as the probability of the outcome, AFF, was expected to be very low.(17, 18) This statistical technique weights individual studies by sample size and variance (both within-and between-study variance) and yields a pooled point estimate of RR and a 95% confidence interval (CI). The DerSimonian and Laird technique was considered an appropriate pooling technique because of the relative heterogeneity of the source population in each study. Subgroup analysis was performed by study design (case-control or cohort design), for studies that used validated outcome definitions, and for studies reporting on duration of bisphosphonate use. The I2 statistic was calculated to determine the amount of variability in the study results that is attributed to the heterogeneity of included studies.(19) To assess the potential for publication bias, we performed the Begg’s and the Egger’s tests and constructed funnel plots to visualize possible asymmetry.(20) Due to the limited number of studies, meta-regression was not performed. All statistical analyses were performed in Comprehensive Meta Analysis version 2.2 (www.meta-analysis.com) and Stata 10 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). We followed the Meta-analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines in the report of this meta-analysis.(21)

Results

Study characteristics and quality

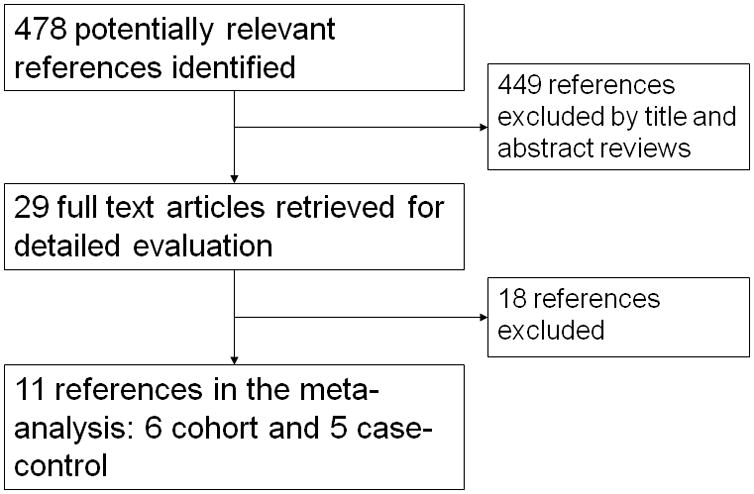

The electronic literature search resulted in 478 potential studies examining bisphosphonates and subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femoral fracture. Further search of abstracts from the ACR, ASBMR, and AAOS meetings from 2006–2012 yielded an additional 24 abstracts for review. After review of study titles and abstracts from these studies, the exclusion criteria listed in the methods section were applied. A total of 29 studies remained and underwent more detailed examination to determine whether they met study criteria. Duplicate studies and studies where fully published study data was not obtainable were excluded. Studies that met all requirements except used only crude estimates of association were excluded from the analysis(22, 23), as were studies that did not present data that allowed for calculation of adjusted relative risk ratio(24). Eleven studies, composed of five case-control and six cohort studies, including one study presenting results from three randomized controlled trials, were used in the final analysis. Figure 1 illustrates our study selection process. Four studies were included in analyses examining long-term bisphosphonate use, which was defined for this meta-analysis as greater than 5 years.

Figure 1.

Selection of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Descriptions of the included studies are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. The study populations were from the U.S, Canada, Europe, and Taiwan. The number of study participants ranged from 477 to 1,521,131 participants. Many studies only included women.(9, 10, 12, 14, 25) Mean ages in the study populations ranged from 68 to 84 years. Most studies examined use of oral bisphosphonates; however, three studies also described intravenous use of zoledronic acid.(11, 12, 26) Most studies compared fractures in users of bisphosphonates to non-users of bisphosphonates, although three studies also compared fracture rates in users of non-bisphosphonate osteoporosis medications.(11, 13, 14) All studies used medical record review and/or ICD codes to find the main outcome of interest, subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures. Several studies confirmed features of atypical fractures with radiologic review(9, 10, 12, 25–27) and two of these studies used the ASBMR criteria for definition of AFF.(26,27) Several studies also examined long-term use of bisphosphonates in a subset of patients.(9, 10, 13, 14, 26, 28, 29) Long-term use was defined differently in each study, varying from greater than one year of bisphosphonate use to greater than six years of bisphosphonate use. Only studies that presented adjusted estimates of association for long-term use were included in the subgroup analysis of long-term bisphosphonate use, which for this study was defined as bisphosphonate use of 5 years or greater. (9, 13, 28, 29) Based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment scale, all the included studies were of moderate to high quality.

Table 1.

Summary of included cohort studies examining the association of bisphosphonate use and subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fractures

| Study, year, country | Subjects | Type of bisphosphonate | Outcome definition and number of events | Variables matched and/or controlled | Quality assessment scores b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrahamsen a, 2009, Denmark 27 | 15,561 women with history of non-hip fracture in a national patient registry (1997–2005) | Alendronate | ST/FS fractures 76 |

Matched on: Sex, birth year, baseline fracture location Adjusted for: Age, sex, and comorbidities |

s3/c2/o2 |

| Abrahamsen a, 2010, Denmark 28 | 197,835 patients without previous hip fracture in a national patient registry (1996–2005) | Alendronate | ST/FS fractures 1049 |

Matched on: Age, sex, index year Adjusted for: Sex, Charlson index, hormone therapy, steroid use, fracture history, and number of co-medications |

s4/c2/o1 |

| Black, 2010, USA 12 | 14,195 women enrolled in three randomized controlled trials examining bisphosphonate use | Alendronate Zoledronic acid |

ST/FS fractures 12 |

Placebo-controlled | s3/c2/o2 |

| Hsiao, 2011, Taiwan 14 | 11,278 women with osteoporosis and prior vertebral/hip fracture in a national insurance database (2001–2007) | Alendronate | ST/FS fractures 61 |

Adjusted for: Age, fracture history, comorbidities, and co-medications | s3/c2/o1 |

| Kima, 2011, USA 13 | 33,815 new-users of bisphosphonates, raloxifene, or calcitonin enrolled in Medicare (1996–2006) | Alendronate Etidronate Risedronate |

ST/FS fractures 104 |

Matched on: Propensity score (encompassing age, race, sex, health care utilization, comorbidities, and co-medications) | s3/c2/o1 |

| Vestergaard, 2011, Denmark 11 | 414,245 patients from a national patient registry (1996–2006) | Alendronate Etidronate Clodronate Ibandronate Pamidronate Risedronate Zoledronic acid |

ST/FS fractures 4,179 |

Matched on: Age, sex Adjusted for: Steroid use, hormone therapy, alcoholism, fracture history |

s3/c2/o2 |

AFF, atypical femur fractures; ST, subtrochanteric; FS, femoral shaft. All studies used International Statistical Classification of Diseases to identify cases, either 8th, 9th or 10th revision, and/or medical record review to identify cases

These studies examined risk associated with bisphosphonate use ≥ 5 years

Maximum score using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale16 is s4/c2/o3. The scoring system is based on selection of cohorts (s), comparability of cohorts (c), and outcome assessment criteria (o).

Table 2.

Summary of included case control studies examining the association of bisphosphonate use and subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fractures

| Study, year, country | Subjects | Type of bisphosphonate | Case definition and number of events | Control definition and number of events | Variables matched and/or controlled | Quality assessment scoresc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenart, 2009, USA 24 | Postmenopausal women at one institution (2000–2007) | Any | ST/FS fractures 41 |

IT/FN fractures 82 |

Matched on: Age, race, body mass index | s2/c2/e3 |

| Park-Wyllie a, 2011, Canada 9 | Women using bisphosphonates in a prescription database (2002–2008) | Alendronate Risedronate Etidronate |

ST/FS fractures 716 |

No ST/FS fractures 3580 |

Matched on: Age, cohort entry period Adjusted for: SES, co-medications, comorbidities, resource utilization, BMD |

s2/c2/e3 |

| Schilcher, 2011, Sweden 10 | Women with age greater than 55 in a national patient registry (2008) | Alendronate Etidronate Ibandronate Risedronate |

Atypical ST/FS fractures 59 |

Typical ST/FS fractures 263 |

Matched on: none Adjusted for: Age, steroid use, Charlson index, hormone therapy, antiepileptic use, antidepressant use, PPI use |

s3/c2/e3 |

| Feldstein b, 2012, USA 26 | Patients in a managed care database (1996–2009) | Any oral bisphosphonate | Atypical FS fractures 75 |

Typical FS fractures 122 |

Matched on: none Adjusted for: Age, sex, steroid use, number of co-medications |

s4/c2/e3 |

| Meier b, 2012 Switzerland 25 | Patients admitted with ST or FS fractures at one institution (1999–2010) | Alendronate Risedronate Pamidronate Ibandronate Etidronate Zoledronic acid |

AFF 39 |

Typical ST/FS fractures 438 |

Matched on: none Adjusted for: Age, sex, vitamin D, steroid, and PPI use |

s2/c2/e3 |

AFF, atypical femur fractures; ST, subtrochanteric; FS, femoral shaft; IT, intertrochanteric; FN, femoral neck; SES, socio-economic status; PPI, proton-pump inhibitors; BMD, bone mineral density; N/A, not available.

All studies used International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 9th or 10th revision, to initially identify outcome. Outcome was then validated with radiologic review.

This study examined risk associated with bisphosphonate use ≥ 5 years

These studies used ASBMR criteria to define AFF.

Maximum score using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale16 is s4/c2/e3. The scoring system is based on selection of cases and controls (s), comparability of cases and controls (c), and

ascertainment of exposure (e).

Bisphosphonates and atypical femur fracture

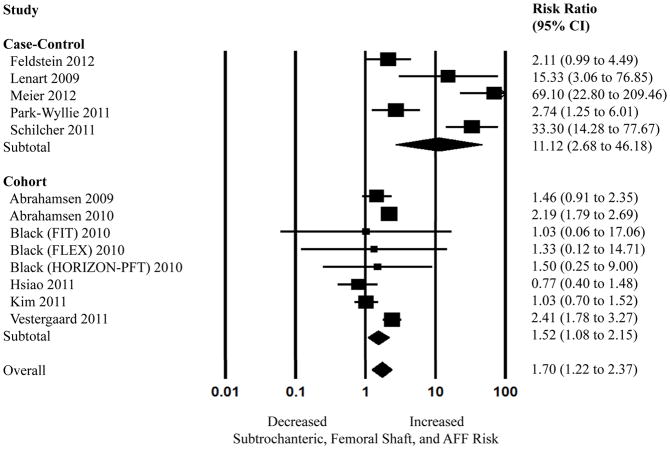

The overall pooled estimate of adjusted risk ratio (RR) for AFF associated with bisphosphonates using data from the five case-control and six cohort studies was 1.70 (95% CI, 1.22–2.37) (Figure 2). A large amount of heterogeneity was noted (I2=89.19%, P<0.05). Exclusion of individual studies that appeared to have much higher RR as compared to the rest of the included studies (10,25,26) did not significantly change the overall pooled adjusted RR. The pooled adjusted RR based on five case-control studies(9, 10, 25–27) was 11.12 (95% CI, 2.68–46.18) with severe heterogeneity (I2=91.13%, P<0.05) and the pooled adjusted RR using only the cohort studies(11–14, 28, 29) was 1.52 (95% CI, 1.08–2.15) with moderate heterogeneity (I2=68.91%, P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Random effects analysis of the studies for the association between bisphosphonate use and subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fracture (AFF), stratified by study design. Point (square) and overall (diamond) estimates are given as risk ratios with 95% confidence interval (CI) (horizontal bar).

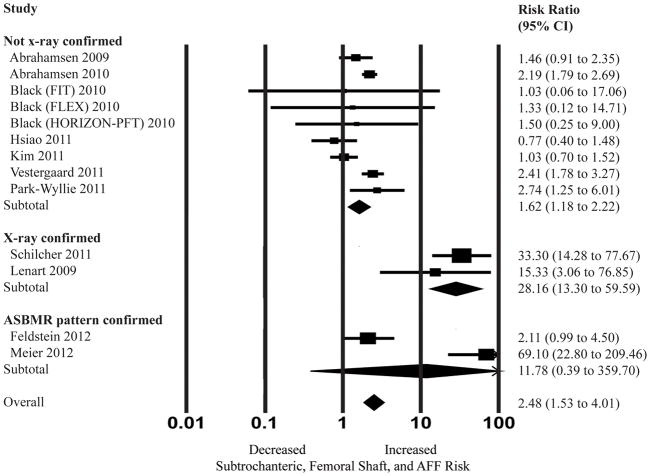

Subgroup analysis was then performed stratifying by outcome definition. The outcome was defined by either; 1) no x-ray confirmation, 2) x-ray confirmation, and 3) ASBMR-pattern confirmation (Figure 3). The pooled adjusted RR based on the two studies which used ASBMR-defined AFF (25, 26) was 11.78 with a wide 95% confidence interval (0.39–359.69) and severe heterogeneity (I2=96.15%, p<0.05). The pooled adjusted RR based on the studies that used x-ray confirmation of fractures (not using ASBMR-defined criteria) as part of their definition for AFF (10, 24) was 28.16 (95% CI 13.30 – 59.59, I2=0% with p=0.40). Lastly, the pooled adjusted RR based on the remaining studies that used primarily ICD codes to define subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures (9, 11–14, 27, 28) was lower at 1.62 (95% CI, 1.18–2.22, I2=65.92% and P<0.05).

Figure 3.

Random effects analysis of the studies for the association between bisphosphonate use and subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fracture (AFF), stratified by outcome definition (x-ray confirmation of fractures and/or confirmation of fractures meeting ASBMR criteria for AFF). Point (square) and overall (diamond) estimates are given as risk ratios with 95% confidence interval (CI) (horizontal bar). aAlthough most cases met the ASBMR-criteria, Feldstein et al did include a small number of cases which did not have the classic “transverse” or “short oblique” fracture angle required for ASBMR definition of AFF.

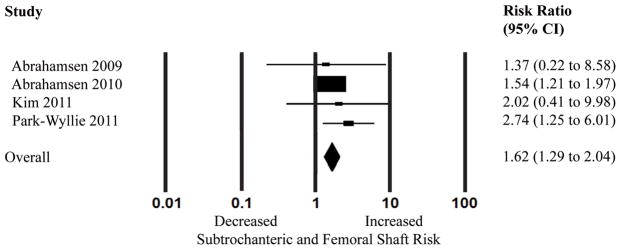

Another subgroup analysis was performed examining long-term use of bisphosphonates (Figure 4). When examining the subset of studies reporting 5 years or greater of bisphosphonate use,(9, 13, 28, 29) the pooled adjusted RR was 1.62 (95% CI 1.29–2.04, I2=0% and p=0.575). None of these studies examining long-term use used the ASBMR criteria for defining AFF.

Figure 4.

Random effects analysis of the studies for the association between long-term bisphosphonate use (5 years or greater) and subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures. Point (square) and overall (diamond) estimates are given as risk ratios with 95% confidence interval (CI) (horizontal bar).

Publication bias assessment

There was no statistical evidence of publication bias among the included studies by using Egger’s (P=0.4) and Begg’s (P=0.5) tests. However, the funnel plot shows minor asymmetry suggesting a small potential publication bias (eFigure 2).

Discussion

Considering the widespread use of bisphosphonates in the United States(3), even rare events that could be associated with these medications raise concern. Atypical femur fractures are one such rare event that is associated with bisphosphonates in several studies. This meta-analysis summarized the available data in published literature exploring a possible association of bisphosphonates and risk of subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures and AFF, and found an increased risk of these fractures with use of bisphosphonates.

We found that this increased risk persists for long-term users of bisphosphonates in our meta-analysis. However, these data should be interpreted with caution, as not only were there a small number of studies included in this sub-group analysis, but it is possible that the risk we found was underestimated considering that the studies included in the long-term analysis did not radiologically confirm atypical fractures.

In our analyses, we noted that three of the case-control studies appeared to have higher RR as compared to the rest of the studies. One potential explanation for this observation is the selection of the controls, which in all these studies were “typical” fractures. In choosing controls that had an outcome for which bisphosphonates are known to have a beneficial effect, these studies could exaggerate any potential harmful association of “atypical” fractures attributable to bisphosphonates (see eFigure 3). In addition, only one of these studies used the ASBMR-criteria for AFF; therefore the other two studies may over-estimate the number of atypical fractures seen in their cohorts. Aspenberg et al. recently presented an abstract re-analyzing the Schilcher et al. published study data using ASBMR-criteria for defining AFF. (30) This study found the RR of AFF with bisphosphonate decreased by more than half using the ASBMR-criteria for AFF as compared to their prior published RR. Similarly, the included Feldstein article27, which in general used ASBMR criteria to define AFF, also included a small number cases which did not have the classic “transverse” or “short oblique” fracture angle required for the ASBMR definition; this may be why the RR is lower than the other study in our meta-analysis which used ASBMR criteria for the outcome definition26. Lastly, it is also possible that part of the discrepancy lies in the studies that used solely ICD codes to diagnosis subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures, which may include a significant portion of fractures that are not AFF and therefore show falsely low RR associated with use of bisphosphonates.

A main limitation in our study is the varying definition of AFF used in the included studies. A task force of the ASBMR suggests that in addition to the subtrochanteric or femoral shaft location, AFF should be defined by additional radiologic and histologic features, such as non-comminuted fractures that occur in a short oblique or transverse configuration with minimal or no trauma.(31) Some studies suggest that only a subset, 17–29%, of subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures meet these criteria for AFF.(31) However, due to inability to radiologically confirm several of these features, many epidemiologic studies have used the location of the fracture, subtrochanteric or femoral shaft, as a marker for AFF, while other studies were able to use the more precise criteria. Nevertheless, including the studies with the broader definition of AFF would likely bias our study towards the null, and despite this we have found a significant risk of AFF with use of bisphosphonates. When only examining the subset of studies that used ASBMR-criteria to confirm AFF we still found a significant association of AFF with bisphosphonates; however, caution should be used in the interpretation of this sub-analysis considering the small amount of studies using ASBMR-criteria, leading to a wide confidence interval and severe heterogeneity.

As is common with meta-analyses, we were also limited by the significant heterogeneity of the studies, with some I2 values greater than 90%. Potential causes of heterogeneity between the studies include variations in the study design and size, patient characteristics (age, gender, race, geographic location, underlying comorbidities and use of other drugs), type of bisphosphonates, type of comparison group (non-users or non-bisphosphonate osteoporosis medications), outcome definition or ascertainment methods, choice of control fracture, statistical methods, and the overall study quality. We used a random effects model to account for both within- and between-study variance for our analysis. We also performed a subgroup analysis by study design, outcome definition, and long-term bisphosphonate use to further explore a potential source of heterogeneity.

All meta-analyses are vulnerable to publication bias, but we attempted to minimize this bias by searching two major electronic databases and abstracts for major scientific meetings related to the topic. We also further examined for publication bias using three different statistical tests. In order to minimize confounding and selection bias that are inherent to observational studies, we objectively assessed the quality of individual studies and all the included studies were of medium to high quality. In addition, we only included studies in the analysis if they reported adjusted relative risks to minimize potential confounding. However, despite these efforts, potential confounding may remain, particularly in some of the included cohort studies that compare bisphosphonate users to those receiving no treatment at all – these studies could be subject to confounding by indication even with full adjustment.

Despite these limitations, this meta-analysis adds to the current literature by providing an in-depth summary and analysis of recent data describing the association of bisphosphonates with subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and AFF. However, while the relative risk of these atypical fractures appears increased among bisphosphonate users in our study, the public health consequences are likely minimal considering the rarity of AFF as compared to typical osteoporotic fractures, especially in the first several years of bisphosphonate treatment. A recent study by Dell and others that did not meet pre-specified criteria to be included for this meta-analysis, found the estimated incidence of AFF among patients older than 45 years was 1.78/100,000 person-years in those taking bisphosphonates for less than two years.(24) Comparatively, in this same population typical hip fracture incidence was 463/100,000 person-years in those taking bisphosphonates for 0–1 years. However, duration of bisphosphonate use increased the incidence of AFF: the incidence of AFF/100,000 person-years ranged from 38.9 for those taking bisphosphonates for 6–8 years, to 107.5 in those taking bisphosphonates for greater than 10 years.(24)

Therefore, while the benefit of bisphosphonates likely outweighs the risk of the rare AFF early on in treatment, this benefit is less clear for long-term users. The US Food and Drug Administration recently reviewed the limited published randomized control trial data examining long-term use of bisphosphonates, and found no clear benefit of long-term use (defined as greater than 5 years) of bisphosphonates in prevention of typical osteoporotic fractures.(32) Black and others however suggest that there may be benefit for the subgroup of patients with persistent T scores less than −2.5 at the femoral neck after 3–5 years of bisphosphonate therapy or those with vertebral fracture.(33)

Considering the above findings, the results of this meta-analysis suggest increased caution may be indicated for bisphosphonate use beyond five years, particularly in the subgroup of patients with no vertebral fractures or T scores greater than −2.5, where there is unclear benefit of typical osteoporotic fracture prevention with bisphosphonates. Further research examining long-term use of bisphosphonates is indicated in order to better define the continued effectiveness of bisphosphonates in osteoporotic fracture prevention and the risk of associated rare side effects.

This meta-analysis shows an increased risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and AFF with bisphosphonate use. However, these atypical femur fractures are rare events even in bisphosphonate users, and their risk is likely to be outweighed by bisphosphonate’s reduction of typical osteoporotic fractures in most patients. Increased caution may be indicated in long-term users where the benefit of bisphosphonates in prevention of typical osteoporotic fractures is less clear; however there is a paucity of data about AFF risk among long-term bisphosphonate users.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

National Institute of Health grants helped to fund this study (author LG - T32AR055885-04, author SCK - K23 AR059677, and author DHS- K24 AR055989, P60 AR047782, R21 DE018750, and R01 AR056215). Author SCK has also received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America and Pfizer, and author DHS has received research support from Abbott Immunology, Amgen and Lilly.

Footnotes

Requests for reprints should be sent to above address.

Supplementary Data: Supplementary data has been included with this submission.

Authors’ roles: Study design: DHS, SCK. Data collection: LG, SCK. Data analysis and interpretations: LG, DHS, SCK. Drafting manuscript: LG. Revising manuscript: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors. LG and SCK take responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Disclosures

Author LG is supported by the NIH grant T32AR055885-04. Author DHS is supported by the NIH grants K24 AR055989, P60 AR047782, R21 DE018750, and R01 AR056215, and has received research support from Abbott Immunology, Amgen and Lilly. Author DHS serves in unpaid roles on two Pfizer sponsored trials. Author SCK is supported by the NIH grant K23 AR059677, and received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America and Pfizer. Author SCK received tuition support for the Pharmacoepidemiology Program at the Harvard School of Public Health funded by Pfizer and Asisa.

References

- 1.National Osteoporosis Foundation. [Access date: April 2012. ];Prevalence report. http://www.nof.org/advocacy/resources/prevalencereport.

- 2.Bilezikian JP. Efficacy of bisphosphonates in reducing fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2009;122:S14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siris ES, Pasquale MK, Wang Y, Watts NB. Estimating bisphosphonate use and fracture reduction among US women aged 45 years and older, 2001–2008. J Bone Miner Res. 26:3–11. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odvina CV, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS, Maalouf N, Gottschalk FA, Pak CY. Severely suppressed bone turnover: a potential complication of alendronate therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1294–301. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mashiba T, Hirano T, Turner CH, Forwood MR, Johnston CC, Burr DB. Suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates increases microdamage accumulation and reduces some biomechanical properties in dog rib. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:613–20. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly MP, Wustrack R, Bauer DC, Palermo L, Burch S, Peters K, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE, Black DM. Incidence of subtrochanteric and diaphyseal fractures in older white women: Data from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. ASBMR Annual Meeting; Toronto, Canada. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieves JW, Bilezikian JP, Lane JM, Einhorn TA, Wang Y, Steinbuch M, Cosman F. Fragility fractures of the hip and femur: incidence and patient characteristics. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0962-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Bhattacharyya T. Trends in incidence of subtrochanteric fragility fractures and bisphosphonate use among the US elderly, 1996–2007. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:553–60. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Hawker GA, Gunraj N, Austin PC, Whelan DB, Weiler PJ, Laupacis A. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. Jama. 2011;305:783–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schilcher J, Michaelsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vestergaard P, Schwartz F, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Risk of femoral shaft and subtrochanteric fractures among users of bisphosphonates and raloxifene. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:993–1001. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1512-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black DM, Kelly MP, Genant HK, Palermo L, Eastell R, Bucci-Rechtweg C, Cauley J, Leung PC, Boonen S, Santora A, de Papp A, Bauer DC. Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur. N Engl J Med. 2010;362 (19):1761–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY, Schneeweiss S, Katz JN, Levin R, Solomon DH. Oral bisphosphonates and risk of subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur fractures in a population-based cohort. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26 (5):993–1001. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsiao FY, Huang WF, Chen YM, Wen YW, Kao YH, Chen LK, Tsai YW. Hip and subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femoral fractures in alendronate users: a 10-year, nationwide retrospective cohort study in Taiwanese women. Clin Ther. 2011;33 (11):1659–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells GS, BO’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. [Access date: July 2012. ];The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2011 www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm.

- 17.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. Jama. 1998;280 (19):1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7 (3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21 (11):1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54 (10):1046–55. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama. 2000;283 (15):2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Dekkers OM, Ramautar SR, Dijkstra S, Papapoulos SE. Atypical fractures and bisphosphonate therapy: a cohort study of patients with femoral fracture with radiographic adjudication of fracture site and features. Bone. 2011;48 (5):966–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo JC, Huang SY, Lee GA, Khandewal S, Provus J, Ettinger B, Gonzalez JR, Hui RL, Grimsrud CD. Clinical correlates of atypical femoral fracture. Bone. 2012;51 (1):181–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.02.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dell RM, Adams AL, Greene DF, Funahashi TT, Silverman SL, Eisemon EO, Zhou H, Burchette RJ, Ott SM. Incidence of atypical nontraumatic diaphyseal fractures of the femur. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(12):2544–50. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenart BA, Neviaser AS, Lyman S, Chang CC, Edobor-Osula F, Steele B, van der Meulen MC, Lorich DG, Lane JM. Association of low-energy femoral fractures with prolonged bisphosphonate use: a case control study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20 (8):1353–62. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0805-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meier RPH, Perneger TV, Stern R, Rizzoli R, Peter RE. Increasing occurrence of atypical femoral fractures associated with bisphosphonate use. Arch Intern Med. 2012 doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldstein A, Black D, Perrin N, Rosales AG, Friess D, Boardman D, Dell R, Santora A, Chandler JM, Rix MM, Orwoll E. Incidence and demography of femur fractures with and without atypical features. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:977–86. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R. Subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures in patients treated with alendronate: a register-based national cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24 (6):1095–102. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R. Cumulative alendronate dose and the long-term absolute risk of subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures: a register-based national cohort analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95 (12):5258–65. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aspenberg P, Schilcher J, Koeppen V. Atypical femoral shaft fractures are a separate entity, easily diagnosed by its radiographic stress fracture characteristics: Analaysis of 59 atypical fractures and 218 controls; Abstract LB-SU18, ASMBR annual meeting; 2012; Minneapolis, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shane E, Burr D, Ebeling PR, Abrahamsen B, Adler RA, Brown TD, Cheung AM, Cosman F, Curtis JR, Dell R, Dempster D, Einhorn TA, Genant HK, Geusens P, Klaushofer K, Koval K, Lane JM, McKiernan F, McKinney R, Ng A, Nieves J, O’Keefe R, Papapoulos S, Sen HT, van der Meulen MC, Weinstein RS, Whyte M. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25 (11):2267–94. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, Benson G. Bisphosphonates for Osteoporosis - Where Do We Go from Here? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2048–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, Cummings SR, Rosen CJ. Continuing bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis--for whom and for how long? N Engl J Med. 2012;366 (22):2051–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.