Senescence is an inbuilt cellular response that leads to irreversible cell cycle arrest.1 It plays a critical role in both aging and tumor suppression. While first observed in culture, cellular senescence happens in vivo. Premature senescence can be triggered by various insults, such as oncogene activation, telomere erosion, irradiation, DNA damage, oxidative stress and toxins, which emphasize the importance of the senescence pathway in arresting growth of prospective cancer cells that have accumulated potentially harmful genetic mutations.1

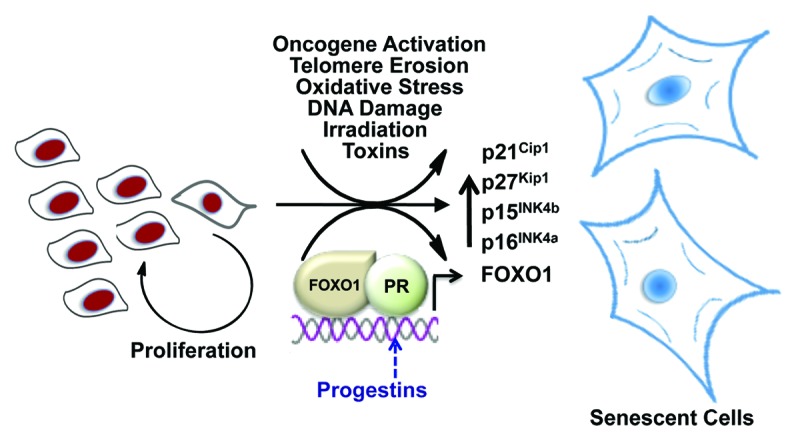

In the May 1, 2013 issue of Cell Cycle, Diep and colleagues report that the progesterone receptor (PR) cooperates with the Forkhead transcription factor FOXO1 to trigger cellular senescence in ovarian cancer cells.2 The authors found that PR not only regulates FOXO1 expression, but also cooperates with this transcription factor to activate genes that encode senescence-associated cell cycle inhibitors, such as p15INK4b, p16INK4a, p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 (Fig. 1). Importantly, they show that this response is induced upon treatment of cells with a synthetic PR agonist, dependent on the B isoform of PR and attenuated upon FOXO1 knockdown. The inference is that progestins, compounds widely used for a variety of clinical indications, could also be valuable in the management of ovarian cancer, the most lethal of all gynecological malignancies.

Figure 1. Progestin-dependent activation of the senescence pathway. Cancer cells have increased capacity to proliferate. Cellular senescence can be triggered by various insults. Progesterone promote ovarian cancer cells to enter senescence through activation of the progesterone receptor (PR), which cooperates with FOXO1 to induce expression of senescence-associated cell cycle inhibitors, including FOXO1, p15INK4b, p16INK4a, p21Cip1 and p27Kip1.

These observations are unexpected for more than one reason. It is generally believed that most cancer cells have disabled the senescence pathway, thus achieving immortality.1 However, the present study shows that PR- and FOXO1-positive ovarian cancer cells can be tricked into entering senescence in response to progestins. The role of FOXO proteins in cellular senescence is well documented.3 In keeping with the findings of Diep et al.,2 it has been shown previously that overexpression or activation of FOXO proteins through inhibition of the upstream phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling cascade promotes senescence via induction of cell cycle inhibitors, such as p27Kip1. Intriguingly, the cellular senescence induced in this way appears to be independent of p53 and p16INK4a, molecules important for the maintenance of senescence-associated cell cycle arrest.3

The present study not only identifies the PR-FOXO1 axis as a potential therapeutic target in ovarian cancer, but also helps to explain why expression of PR is a prognostic marker for ovarian cancer associated with longer progression-free survival. Similarly, this study provides a mechanistic explanation for why pregnancy, which is associated with high circulating progesterone levels, and the use of progestin-containing oral contraceptives may suppress the growth of premalignant cells in the ovarian cortex, thus protecting against ovarian cancer.4 There are, however, major obstacles that limit the clinical use of progestins in ovarian cancer. Foremost, ovarian cancer is a heterogeneous disease that consists of etiologically distinct tumors that share an anatomical site. Consequently, progestin sensitivity is likely restricted to certain histological types, such endometrioid and serous cancers.4 Further, PR as well as FOXO1 are frequently lost in ovarian cancer; the robustness of the senescence response in vivo has not yet been studied, and the contribution of putative non-genomic progestin receptors in modulating cellular responses to hormonal therapies remains poorly understood and controversial.5 Nevertheless, the observations of Diep and colleagues should help to define molecular markers that identify those tumors likely to be responsive to progestin treatment, alone or combined with a PI3K/AKT inhibitor.

Notably, PR and FOXO1 interactions have also been studied in normal and malignant endometrium.6,7 In fact, these two transcription factors are also putative determinants of the responsiveness of endometrial cancer cells to chemotherapy and progestin treatment. In the context of reproduction, the induction of FOXO1 and subsequent binding to PR triggers the differentiation of endometrial stromal cells into secretory decidual cells,7 a process that is indispensable for embryo implantation and the formation of a functional placenta. Few studies have as yet examined senescence in decidual cells, although there is evidence that deregulation of this process can cause preterm labor.8 Approximately 12.9 million babies are born too soon every year, and more than 1 million die each year as a direct consequence of prematurity. Thus, targeting the FOXO1-PR axis to modulate cellular senescence in the uterus or ovary may unlock hitherto unrecognized therapeutic options of immense clinical value.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/25070

References

- 1.Collado M, Serrano M. Senescence in tumours: evidence from mice and humans. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:51–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diep CH, Charles NJ, Gilks CB, Kalloger SE, Argenta PA, Lange CA. Progesterone receptors induce FOXO1-dependent senescence in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:1433–49. doi: 10.4161/cc.24550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collado M, Medema RH, Garcia-Cao I, Dubuisson ML, Barradas M, Glassford J, et al. Inhibition of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway induces a senescence-like arrest mediated by p27Kip1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21960–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modugno F, Laskey R, Smith AL, Andersen CL, Haluska P, Oesterreich S. Hormone response in ovarian cancer: time to reconsider as a clinical target? Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:R255–79. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gellersen B, Fernandes MS, Brosens JJ. Non-genomic progesterone actions in female reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:119–38. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goto T, Takano M, Albergaria A, Briese J, Pomeranz KM, Cloke B, et al. Mechanism and functional consequences of loss of FOXO1 expression in endometrioid endometrial cancer cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:9–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Labied S, Kajihara T, Madureira PA, Fusi L, Jones MC, Higham JM, et al. Progestins regulate the expression and activity of the forkhead transcription factor FOXO1 in differentiating human endometrium. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:35–44. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirota Y, Daikoku T, Tranguch S, Xie H, Bradshaw HB, Dey SK. Uterine-specific p53 deficiency confers premature uterine senescence and promotes preterm birth in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:803–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI40051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]