Abstract

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Recent evidence indicates that tumors contain a subpopulation of cancer stem cells (CSCs) that are responsible for tumor maintenance and spread. CSCs have recently been linked to the occurrence of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Neurotrophins (NTs) are growth factors that regulate the biology of embryonic stem cells and cancer cells, but still little is known about the role NTs in the progression of lung cancer. In this work, we investigated the role of the NTs and their receptors using as a study system primary cell cultures derived from malignant pleural effusions (MPEs) of patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. We assessed the expression of NTs and their receptors in MPE-derived adherent cultures vs. spheroids enriched in CSC markers. We observed in spheroids a selectively enhanced expression of TrkB, both at the mRNA and protein levels. Both K252a, a known inhibitor of Trk activity, and a siRNA against TrkB strongly affected spheroid morphology, induced anoikis and decreased spheroid forming efficiency. Treatment with neurotrophins reversed the inhibitory effect of K252a. Importantly, TrkB inhibition caused loss of vimentin expression as well as that of a set of transcription factors known to be linked to EMT. These ex vivo results nicely correlated with an inverse relationship between TrkB and E-cadherin expression measured by immunohistochemistry in a panel of lung adenocarcinoma samples. We conclude that TrkB is involved in full acquisition of EMT in lung cancer, and that its inhibition results in a less aggressive phenotype.

Keywords: cancer stem cells, neurotrophins, pleural effusions, lung cancer, TrkB

Introduction

Despite considerable progress in both diagnosis and therapy, lung cancer, remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. It represents a huge medical burden and a major therapeutic challenge. Lung cancer, despite a generally good initial response to chemotherapy, displays a poor prognosis because of disease relapse and metastasis, which are responsible for the unfavorable clinical outcome.1,2 Usually, cancer cells display a wide spectrum of genetic, functional and morphological heterogeneity, and this represents a big obstacle to the development of therapies able to target all possible driver mutation in lung cancer.3 Furthermore, it has been shown that lung cancer is continuously sustained by a population of cancer stem cells (CSCs) with unique properties, such as longevity, quiescence and self-renewal potential.4,5 CSCs have recently been shown to acquire markers of epithelial-to-mesenchymal (EMT) transition, a phenotypic change of cancer cells associated with a more aggressive and metastatic behavior because of the reduced expression of cell-to-cell adhesion molecules and the increased expression of cell motility markers.6,7 The current hypothesis suggests that CSCs that have undergone EMT transition are responsible for the reconstitution of tumor masses after cytoreductive therapy because of their intrinsic resistance to chemotherapy and propensity to metastasize.8 Therefore it is of utmost importance to further identify molecular mechanisms deregulated in CSCs that contribute to disease aggressiveness.

The family of human neurotrophins (NTs) consists of four structurally and functionally related polypeptides: nerve growth factor (NGF); the prototypic NT, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF); neurotrophin (NT)-3 and neurotrophin 4/5 (NT-4/5). NTs may be distinguished based upon their distinct patterns of spatial and temporal expression and their different effects on cellular targets.9,10 NTs exert their biological effects through binding to two unrelated classes of cell surface receptors. All NTs bind to a trans-membrane protein, the p75 receptor, which belongs to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family and to distinct members of a super-family of high affinity tyrosine kinase receptors known as Trks.11 NGF is the preferred ligand for TrkA; BDNF and NT-4/5 are preferred ligands for TrkB and NT-3 for TrkC. NTs have an important role in the growth, development and maintenance of neurons in both the central and peripheral nervous systems. Recent evidences indicate that NTs may play a mitogenic role in the modulation of certain human malignancies, including those of neurogenic and ectodermal origin.12 They are involved in the stimulation of clonal growth of human lung cancer cells in vitro via high-affinity NT receptors.13-17 However, there are still limited data on the expression and the functional significance of NTs in the biology of lung cancer stem cells.

In this paper, we have investigated the role of Trk receptors and their ligands in cancer-initiating cells from adenocarcinoma of the lung, using as model system primary cell cultures derived from patients with malignant pleural effusions.18 This system has been shown to reproduce the natural heterogeneity of NSCLC and to constitute an excellent source of tumor-initiating cells because of their capability to give rise to tumors with histopathological features similar to those of original human tumors when propagated “in vivo” in immunodeficient hosts.19,20 We have also shown that the “in vitro” spheroid forming assay with MPE-derived cells allows the study CSC propagation and its relationship with EMT transition.21 Using this cell system, we demonstrate that TrkB has a key role in the acquisition of a full EMT phenotype in lung cancer cells.

Results

TrkB and its ligand BDNF are selectively upregulated in MPE-derived spheroids

We have previously shown that it is possible to establish tumor cultures from malignant pleural effusions (MPEs) of patients with lung adenocarcinoma with a high rate of success. When grown as spheroids, primary cultures from MPEs are enriched for the expression of cancer stem cell-associated markers such as ALDH and transcription factors Nanog and Oct-4.21

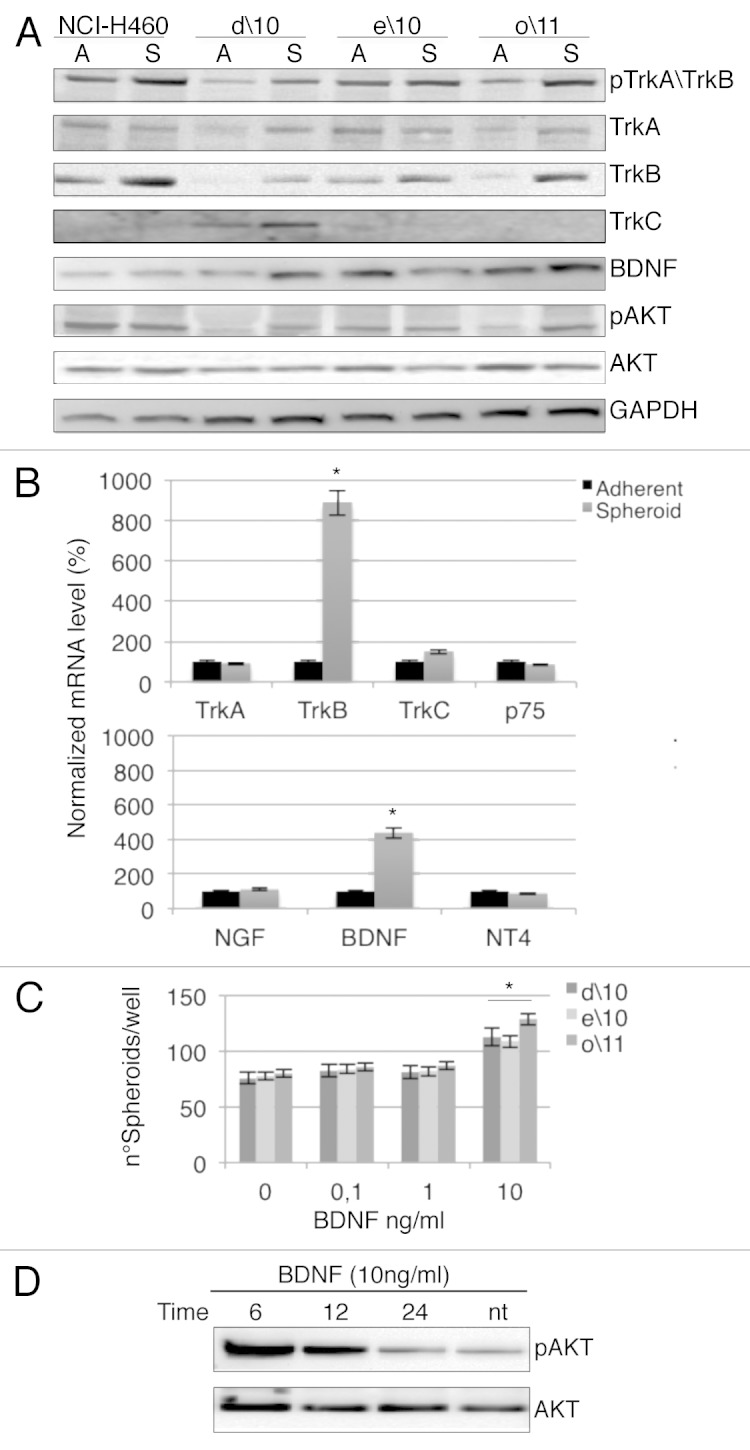

In the present study, we decided to focus our attention on three cultures derived from different patients, namely d\10, e\10, o\11 and the stable lung adenocarcinoma cell line NCI-H460. In order to study the involvement of Trk receptors, we assessed by western blotting the expression level of TrkA, TrkB and TrkC in adherent and spheroids cultures. Interestingly, we observed in almost all cases that the only neurotrophin receptor constantly upregulated in spheroids vs. adherent cultures was TrkB.22 Moreover, an increased level of phosphorylated TrkA/TrkB was detected in cancer spheroids. Consistent with this, phosphorylation of Akt, a downstream effector of Trk activation, was often increased in spheroids. Furthermore, upregulation of BDNF expression in spheroids was observed in o\11 and d\10 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. (A) Representative western blot obtained using anti-phosphorylated TrkA/TrkB and total TrkA, TrkB, TrkC, BDNF antibodies in adherent vs. spheroid cultures. Expression of phosphorylated Akt (phospho-Akt) or total Akt is also demonstrated in primary cell cultures. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Representative RT-PCR analysis in spheroid vs. adherent cultures of Trk and specific ligands. Normalization with housekeeping gene (GAPDH). The data are the mean +/− SD of three independent experiments. *p < 0. 01 vs. adherent cell cultures. (C) Spheroid cells were incubated in the presence of the indicated concentration of BDNF and evaluated for spheroid formation. *p < 0. 05 vs. untreated cells. The number of spheroids were evaluate by optically count. (D) Representative western blot of phosphorylation of Akt in o/11 spheroid culture stimulated at different times with 10 ng/ml of BDNF.

In agreement with western blotting data, when we measured transcriptional levels of neurotrophin receptors and their relative ligands by qPCR, we observed that in all cell lines, only TrkB and BDNF mRNA underwent significant upregulation in spheroids (Fig. 1B). In a spheroid-forming assay, the addition of recombinant BDNF caused a slight but significant increase of spheroid numbers at high doses (10 ng/ml) (Fig. 1C). Finally, to further confirm the involvement of TrkB signaling, we observed a strong but transient increase of Akt phosphorylation in o/11 spheroids treated with the same dose of BDNF (Fig. 1D).

Inhibition of TrkB by K252a impairs spheroidogenesis

We next analyzed the role of TrkB using K252a, a known inhibitor of Trk receptor function, in the formation of spheroids.23 d\10, e\10 and o\11 spheroid cells were generated in the presence of increasing doses of K252a, and the number of spheroids was assessed after 15 d of treatment. Interestingly, the number of spheroids decreased in a dose-dependent manner, reinforcing the hypothesis of a critical role of the Trks.

More importantly, inhibition of spheroid formation was partially but consistently restored by the addition of BDNF, suggesting that the effect was mainly due to inhibition of TrkB activity (Fig. 2A). Moreover, K252a caused a strong induction of anoikis on spheroid cultures (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. (A) d/10, e/10 and o/11 spheroids were incubated in the presence of the indicated concentration of K252a with or without constant 10 ng/ml of BDNF for 15 d, and spheroids were counted. The data are mean +/− SD of three independent experiments. (B) Spheroids were treated with K252a (3 μM) for 72 h. Annexin V was evaluated by flow cytometry. *p < 0.01 vs. untreated cells.

In contrast, when the effect of K252a on cell proliferation was assessed on adherent cell cultures we observed a much lower sensitivity, with IC50 values 14–55-fold higher than those observed on spheroids (Table 1). Hence, spheroid cultures are more sensitive to Trk inhibitors than adherent cultures, which suggests that Trk activity is specifically required for the propagation of CSCs.

Table 1. IC50 values of adherent and spheroids cultures.

| Cell cultures | IC50 K252a (μM) adherent | IC50 K252a (μM) spheroid | Fold of sensitization |

|---|---|---|---|

| d/10 | 4,5 | 0,21 | 21,48 |

| e/10 | > 10 | 0,18 | 55,5 |

| o/11 | 1,4 | 0,1 | 14 |

Primary cell cultures growth in the presence or absence of indicate concentration of K252a. Adherent cultures were evaluated using MTT assay (Sigma Aldrich) and spheroid conditions were evaluated by optically count. The dose-response curves were defined as 50% of the inhibitory concentration (IC50) with KaleidaGraph software.

TrkB and E-cadherin expression are inversely related in human adenocarcinoma of the lung

In order to establish a potential relationship between TrkB and EMT in human lung tumors, we compared by immunohistochemistry the expression of TrkB with that of the epithelial marker E-cadherin in paraffin-embedded sections from 62 adenocarcinomas of the lung. For TrkB immunoreaction, only cytoplasmatic immunopositivity was considered, while for E-cadherin only membrane immunoreactivity. Based upon the percentage of positive cells for each marker, all cases were assigned to one of three distinct groups: no expression, low expression (less than 50% positivity) and high expression (> 50% positive cells) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Immunohistochemistry staining of TrkB and E-cadherin in three human lung adenocarcinoma samples. All figures are 20×, the insert are 40×. (A) Refers to the expression of TrkB: A1, no expression; A2, low expression; A3, high expression. (B) Refers to the expression of E-cadherin: B1, high expression; B2, low expression; B3, no expression.

Forty-three of 62 (69.4%) cases were positive for TrkB (low plus high expressors); interestingly, of these, 29/43 (67.5%) showed only staining for TrkB with no expression of E-cadherin. Thirty-one of 62 cases (47%) were positive for E-cadherin expression (low plus high expressors), the majority of which, 17/31 (55%) displayed no expression of TrkB. Chi-square analysis of these data showed a statistically significant negative relationship (Pearson’s R = −0.649) between TrkB and E-cadherin expression (p < 0.001) (Table 2). These data strongly suggest a direct relationship between TrkB and EMT in adenocarcinoma of the lung.24

Table 2. TrkB and E-cadherin expression by immunohistochemistry staining (total cases 62).

| TrkB° | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No expression | Low expression | High expression | ||

| No expression | 2 | 11 | 18* | |

| E-cadherin° | Low expression | 9 | 9 | 5 |

| High expression | 8* | 0 | 0 | |

p value < 0.001; °cases of human lung adenocarcinoma.

K252a reduces the expression of vimentin in spheroid cultures

In the previous sections we have shown that expression of TrkB is inversely correlated with E-cadherin “in vivo” in human lung adenocarcinoma tissue sections and that its function is required for efficient spheroid formation ex vivo. Therefore, we decided to assess whether TrkB is also involved in the expression of EMT markers in lung cancer spheroids. We focused our attention on the o/11 cell line because it shows a remarkable ability to form large, compact and serially expandable spheroids (Fig. S1). Importantly o/11 cells area capable to give rise to tumor masses in immunodeficient mice when injected as spheroids but not when an equivalent number of adherent cells are implanted (Fig. S2). This culture has high basal levels of ALDHbr cells when grown in adherent conditions, which are further enhanced in spheroids. Furthermore, also Nanog and Oct-4 levels are enhanced at least 10-fold as measured by quantitative PCR in spheroid cultures.21 By immunocytochemistry o/11 spheroids express high levels of vimentin and not E-cadherin expression (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. (A) Immunocytochemistry staining of TrkB, vimentin and E-cadherin in spheroid cells after 72 h treatment with K252a (3 μM). (B) o/11 spheroid cultures treated with K252a [(3 μM) and/or BDNF (10 ng/ml)]. The expression of phosphorylated TrkA/TrkB and total TrkB, vimentin and E-cadherin was assessed by western blot. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

When we generated o/11 spheroids in the presence of K252a and or BNDF, we observed a strong reduction in the expression of vimentin; however, E-cadherin expression was not restored (Fig. 4B). These results were also confirmed by immunocytochemistry analysis: treatment with K252a induced a modification in morphology and size of spheroids, with prominent reduction of staining for vimentin but no reacquisition of E-cadherin (Fig. 4A).

Silencing of TrkB reduces the formation of spheroids and strongly affects vimentin expression in EMT spheroid cultures

In order to gain further insights into the role of TrkB in EMT in spheroid cultures, we performed gene-silencing studies with specific siRNA for TrkB able to strongly affect mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 5A). As expected, cells transfected with siTrkB decreased their capability to form spheroids (Fig. 5B), and this was accompanied by an increase of anoikis (Fig. S3). The role of TrKB in spheroids formation was also confirmed in a quantitative spheroid-forming assay (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. (A) Validation of siTrkB transfection in spheroid cultures by RT-PCR using scramble siRNA as control. *p < 0. 01 vs. scramble siTrkB. Correspondent low TrkB expression confirm by western blot (upper panel) and immunocytochemistry analysis (lower panel). (B) Alteration of morphology and size in siTrkB spheroids compared with control siRNA (scramble) transfected cells. (C) The spheroids proliferation assay was impaired after TrkB knockdown compared with scramble. *p < 0.05 vs. untreated cells.

We wondered whether silencing of TrkB could impair EMT. When we analyzed the mRNA levels of the main transcriptional factors involved in EMT process, indeed, we observed an increased level of Snail, Twist and Slug in CSC spheroids compared with adherent cultures (Fig. 6A). In contrast, silencing of TrkB determined a downregulation of the mesenchymal marker vimentin, both at the protein and mRNA level. These results were confirmed by immunocytochemical analysis (Fig. 6B). Moreover, TrkB silencing was associated with a statistically significant decrease of Slug, Twist and Snail (Fig. 6C), although, also in this case, no significant regain of E-cadherin expression was observed (Fig. 6D). Taken together these data suggest that TrkB is contributing to EMT, and that its inhibition causes a partial reversion (MET, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition) of this process.25-27

Figure 6. (A) Expression of transcriptional factor of EMT markers in primary cell cultures. RT-PCR showing increased mRNA level of Slug, Twist, Snail decreased in spheroid compared with adherent cells. (B) RT-PCR showing mRNA level of vimentin in siTrkB-transfected spheroids, confirmed by western blot analysis and immunocytochemistry staining. (C) siTrkB-transfected spheroid cultures showed statistically significant decrease of Slug, Twist and Snail compared with scramble. (D) Level of E-cadherin in TRkB-transfected spheroids was evaluated by RT-PCR, western blot and immunochemistry analysis. The present data are mean +/− SD of three independent experiments. **p < 0. 05 *p < 0. 01 vs. adherent cell cultures.

Discussion

The majority of cancer patients die of metastatic disease. The process of metastasis formation has been correlated with the ability of cancer cells in the primary tumor site to acquire a migratory mesenchymal state called epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), extravasate into vessels and migrate to a distant site, where they undergo the reverse process, called mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), in order to generate new tumor masses.28,29 This dynamic behavior of cancer-initiating (cancer stem) cells is most likely due to a metastable epigenetic program, which is modulated by microenvironmental cues.30 Based upon the clinical relevance of EMT and the reverse MET, several efforts have been directed in recent years to identify factors that influence EMT also because of the concept that their targeting may be a powerful strategy to improve therapy of cancer.

Growing evidence is accumulating in support of the role of neurotrophins and their receptors, in particular TrkB, in malignant transformation in several types of cancer of epithelial origin. In particular, Okamura et al. have recently reported that TrkB is a negative prognostic factor in lung cancer.24 In this respect, recent literature has suggested that TrkB is one of the inducers of EMT in various types of cancers, including lung, head and neck and colorectal.27,31,32 However, while previous work has been performed primarily on immortalized epithelial cells, we have decided to investigate the role of Trk receptors on a set of primary cultures derived directly from malignant pleural effusions of patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung because of their established capability to give rise to tumors “in vivo” and to propagate “in vitro” as spheroid cultures.20 The ability of cells to grow in conditions of non-adherence is linked to resistance to anoikis (detachment-induced apoptosis), and TrkB has been previously shown to act as a potent suppressor of anoikis.32-34 Indeed we observed in our collection of MPE-derived cultures that TrkB and its ligand BDNF, but not other members of the same families, are constantly upregulated upon switching from adherent cultures to spheroids.

We have previously shown that MPE-derived spheroids are enriched in CSC-related markers such as ALDH and transcription factors Nanog and Oct-4. Therefore, we went to examine whether inhibition of TrkB either by RNA interference, or by the small-molecule inhibitor K252a, would result in impaired spheroid formation. K252a was used because it was previously shown to prevent Akt activation in response to BDNF, to induce apoptotic cell death and diminish the ability of A549 lung cancer cells to grow in soft agar.23 In both cases we saw that TrkB inhibition resulted in a lower number of smaller and disaggregated spheroids where cells showed pronounced signs of anoikis. The most interesting finding, however, was the striking difference observed in the sensitivity of spheroids formation vs. proliferation of adherent cells, which ranged from 14- to approximately 55-fold. These data clearly indicate that TrkB is more required for the maintenance of cells with slow proliferation that are still capable of growing in non-adherent conditions, rather than for the survival of progenitor and terminally differentiated cells.

Previous studies have shown that the ability of TrkB to inhibit anoikis and to induce EMT is linked to the stimulation of a Snail-Twist-Zeb1 axis.32,35 Although in our study we have not assessed Zeb1 expression in our MPE-derived cultures, we also find a strict correlation between TrkB expression and function on one side and Snail, Twist and Slug transcription factors on the other. Conversely, TrkB inhibition during spheroid formation induces a strong inhibition in the expression of these factors, primarily Snail, and all this goes in parallel with a profound change in spheroid morphology. Recently, in breast cancer, microRNAs of the miR-200 family have been demonstrated to be able to target a TrkB/NT3 autocrine loop and to restore anoikis by destabilizing the expression of several factors involved in EMT.36,37 Therefore it will be interesting to assess whether in our system miR-200 family members are involved in a similar type of process.

In line with previous findings, we observed in our MPE-derived cells that TrkB inhibition causes a reversion of EMT with loss of vimentin expression. However, this was never complete, because we were unable to obtain restoration of E-cadherin expression. This is in contrast with previous data in other cellular systems and also with our findings in primary tumor lesions of a strong inverse relationship between TrkB and E-cadherin expression.33 Although we don’t have a precise explanation, we believe that this has to do either with incomplete inhibition of TrkB activity or with the involvement of redundant pathways. Indeed, in TrkB-silenced spheroids, we still observe some residual Twist and Slug expression. It is important to stress however, that the TrkB inhibitor K252a is still able to inhibit spheroid propagation with a submicromolar IC50, and that in preliminary in vivo studies, spheroids generated in the presence of siRNA against TrkB are unable to implant in immunodeficient mice (data not shown).

TrkB inhibition appears therefore as a promising approach to selectively affect cancer-initiating cells in MPE-derived cultures and impair their EMT switch. This deserves further investigations in in vivo studies designed to assess the ability of TrkB inhibitors to affect disease recurrence and metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Primary cell cultures from malignant pleural effusions

To purify tumor cells, malignant pleural effusions (MPEs) were subjected to discontinuous density gradient centrifugation. Recovered cells were cultured in adherent condition in RPMI-1640 (Gibco) supplement with 10% FBS (Gibco). Spheroids cultures were obtained by plating single cells at clonal density in serum-free medium supplemented with basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) and epidermal growth factor (Sigma Aldrich) as previously described.20 All the experiments were performed with the second spheroid cultures obtained by Accumax (Sigma Aldrich) disaggregation. All the experiments were approved by Hospital Ethics Committee 2010 (504/10), and all patients agreed to participate to the study and signed an informed consent form.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer. The primary antibodies used were the following: phospho-TrkA (tyr490)/TrkB (tyr516) (Cell Signaling), TrkA, TrkB, TrkC (Santa Cruz), BDNF, phospho-Akt (ser473), Akt (Cell Signaling), vimentin and E-cadherin (Dako Cytomatic) and GAPDH (Sigma Aldrich). Secondary antibodies were purchased from AbCam. The lysates were separated on SDS/PAGE acrylamide gel and transferred on nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked and incubated with the appropriate primary antibody, followed by the secondary antibody HRP-conjugated (Sigma Aldrich) and developed with ECL chemiluminescent substrate kit (GE Heathcare Amersham). Densitometric analysis was performed using ChemiDoc XRS System (Biorad), and all results were normalized over β-actin or GAPDH.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA of spheroids and adherent cells was extracted with TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen). Two hundred ng of RNA was treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed with Superscript™ first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR green (Bioline sensimix). The primers used for individual genes were indicated in Table S1. Forward and reverse primers for Nanog and Oct4 were described previously GAPDH was included for the normalization of the real time RT-PCR.20

MTT assay

Adherent cultures were plated and after 24 h were treated or not with the indicated concentration of K252a; cellular growth was evaluated using MTT assay (Sigma Aldrich). 96 h after treatments, MTT was added to cells to induce the MTT-formazan product. The dose-response curves were defined as 50% of the inhibitory concentration (IC50) with KaleidaGraph software.

siRNA transfection

A pool of three small interfering RNAs targeting TrkB (Santa Cruz) or control siRNA-A (Santa Cruz) were used to perform silencing experiments. Transfection was performed for 48 h using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagents (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Spheroid-forming assay

Cells were plated as single cells in ultralow attachment plates and were grown in sphere medium with 0.8% methylcellulose with or without the Trk inhibitor K252a (Sigma Aldrich), BDNF (Prepotech), at the indicated concentrations for 15 d. The number of formed spheroids was counted under an inverted optical microscope.

Immunocytochemistry

o/11 spheroid cells were subjected to cytospins centrifuged at 500 rpm for 2 min. The slides were allowed to dry overnight and fixed with formaldehyde 4% for intra-cytoplasmatic antigens. The primary antibodies used were anti-TrkB (Santa Cruz), anti-E-cadherin and anti-vimentin (Dako Cytomatic). Slides were treated with avidin-biotin complex using a DAKO Cytomatic LSAB+Syste-HRP detection system and following the manufacturer’s instructions. Staining was performed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidin and counterstaining with HE. The primary antibodies were omitted and replaced with pre-immune serum in the negative control.

Apoptosis assay

Analysis of apoptosis in adherent and spheroid cells was performed by flow cytometry using Alexa fluor 488-Annexin V (Invitrogen). For K252a treatments, o/11 spheroid cultures were treated or not with this inhibitor (3 μM) for 72 h before analysis. For silencing experiments, spheroids were transiently transfected with siTrkB or scramble for 48 h before analysis. Both samples were incubated with Annexin V antibody according to the recommendation of the manufacturer, and they were analyzed using MacsQuant Flow Cytometer (Miltenyi Biotech).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on slides from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues, corresponding to 62 surgical specimens of human lung adenocarcinoma cases, to evaluate the expression of TrkB, vimentin and E-cadherin markers. The slides were incubated with primary antibody against human TrkB (Santa Cruz), vimentin (Novocastra) and E-cadherin (DAKO Cytomatic). The sections were incubated with biotin-conjugated secondary antibody formulation that recognized mouse and rabbit immunoglobulin. Then the sections were incubated with Novocastra StreptavidinHRP (RE7104) and then peroxidase reactivity was visualized using a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB). Finally, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted. Results are interpreted using a light microscope. Human brain histological specimens were used as TrkB-positive controls.

ALDH activity assay

Growing cells in spheroid conditions were collected and analyzed for ALDH1 activity using ALDEFLUOR kit (Stem Cell Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells incubated with DEAB, a specific inhibitor of ALDH1, were used to establish the background signal that was defined as 0.2 for all samples. Data were analyzed on MACSQuant Analyzer Flow Cytometer.

Animal studies

All studies have been performed in accordance with “Directive 86/609/EEC on the protection of Animals used for Experimental and other scientific purposes” and made effective in Italy by the Legislative Decree DL 116/92. Animal used were 6-wk-old CD1 nude mice (Charles River Laboratories, Inc). After 1 week of acclimatization, they were housed five to a plastic cage and fed on basal diet (4RF24, Mucedola S.r.l.) with water ad libitum, in an animal facility controlled at a temperature of 23 ± 2°C, 60 ± 5% humidity and with a 12 h light and dark cycle. All animal protocols used for this study were reviewed and approved by TakisEthical Committee (n. TKEC-2012-02). Single-cell suspension was obtained by enzymatic digestion of the spheroids, and animals were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 viable cells resuspended in 100 ml of a 50% GFR Matrigel (BD Biosciences) solution. Tumors were measured with a caliper at weekly intervals, and tumor volumes were calculated using the formula; (length × width2)/2. At the end of the studies, mice were sacrificed and tumors excised.

Statistical analysis

All results were presented as ± standard deviations (SD) of three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using unpaired Student’s t-test. The association between TrKB and E-cadherin expression was conducted using Pearson chi-square test and was considered statistically significant with p value < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grant from AIRC [Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (IG 10334)] to G. Ciliberto.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/24759

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/24759

References

- 1.Collins LG, Haines C, Perkel R, Enck RE. Lung cancer: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giangreco A, Groot KR, Janes SM. Lung cancer and lung stem cells: strange bedfellows? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:547–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-984PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakobsen JN, Sørensen JB. Intratumor heterogeneity and chemotherapy-induced changes in EGFR status in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:289–99. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1791-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke MF, Fuller M. Stem cells and cancer: two faces of eve. Cell. 2006;124:1111–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eramo A, Haas TL, De Maria R. Lung cancer stem cells: tools and targets to fight lung cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4625–35. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soini Y. Tight junctions in lung cancer and lung metastasis: a review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:126–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Zhang L, Wang C. CCL21 modulates the migration of NSCL cancer by changing the concentration of intracellular Ca2+ Oncol Rep. 2012;27:481–6. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cioce M, Ciliberto G. On the connections between cancer stem cells and EMT. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:126–36. doi: 10.4161/cc.22809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zermeño V, Espindola S, Mendoza E, Hernández-Echeagaray E. Differential expression of neurotrophins in postnatal C57BL/6 mice striatum. Int J Biol Sci. 2009;5:118–27. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchman VL, Davies AM. Different neurotrophins are expressed and act in a developmental sequence to promote the survival of embryonic sensory neurons. Development. 1993;118:989–1001. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman WJ, Greene LA. Neurotrophin signaling via Trks and p75. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:131–42. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricci A, Greco S, Mariotta S, Felici L, Bronzetti E, Cavazzana A, et al. Neurotrophins and neurotrophin receptors in human lung cancer. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:439–46. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.4.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oelmann E, Sreter L, Schuller I, Serve H, Koenigsmann M, Wiedenmann B, et al. Nerve growth factor stimulates clonal growth of human lung cancer cell lines and a human glioblastoma cell line expressing high-affinity nerve growth factor binding sites involving tyrosine kinase signaling. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2212–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Påhlman S, Hoehner JC. Neurotrophin receptors, tumor progression and tumor maturation. Mol Med Today. 1996;2:432–8. doi: 10.1016/1357-4310(96)84847-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu ZW, Friess H, Wang L, Di Mola FF, Zimmermann A, Büchler MW. Down-regulation of nerve growth factor in poorly differentiated and advanced human esophageal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(1A):125–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Missale C, Codignola A, Sigala S, Finardi A, Paez-Pereda M, Sher E, et al. Nerve growth factor abrogates the tumorigenicity of human small cell lung cancer cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5366–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rakowicz-Szulczynska EM, Koprowski H. Antagonistic effect of PDGF and NGF on transcription of ribosomal DNA and tumor cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163:649–56. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(89)92186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricci A, Mariotta S, Pompili E, Mancini R, Bronzetti E, De Vitis C, et al. Neurotrophin system activation in pleural effusions. Growth Factors. 2010;28:221–31. doi: 10.3109/08977191003677402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basak SK, Veena MS, Oh S, Huang G, Srivatsan E, Huang M, et al. The malignant pleural effusion as a model to investigate intratumoral heterogeneity in lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mancini R, Giarnieri E, De Vitis C, Malanga D, Roscilli G, Noto A, et al. Spheres derived from lung adenocarcinoma pleural effusions: molecular characterization and tumor engraftment. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giarnieri E, De Vitis C, Noto A, Roscilli G, Salerno G, Mariotta S, et al. EMT markers in lung adenocarcinoma pleural effusion spheroid cells. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:1720–6. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pyle AD, Lock LF, Donovan PJ. Neurotrophins mediate human embryonic stem cell survival. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:344–50. doi: 10.1038/nbt1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez-Pinera P, Hernandez T, García-Suárez O, de Carlos F, Germana A, Del Valle M, et al. The Trk tyrosine kinase inhibitor K252a regulates growth of lung adenocarcinomas. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;295:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamura K, Harada T, Wang S, Ijichi K, Furuyama K, Koga T, et al. Expression of TrkB and BDNF is associated with poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;78:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan F, Samuel S, Evans KW, Lu J, Xia L, Zhou Y, et al. Overexpression of Snail induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and a cancer stem cell-like phenotype in human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Med. 2012;1:5–16. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujikawa H, Tanaka K, Toiyama Y, Saigusa S, Inoue Y, Uchida K, et al. High TrkB expression levels are associated with poor prognosis and EMT induction in colorectal cancer cells. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:775–84. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong D, Li Y, Wang Z, Sarkar FH. Cancer Stem Cells and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)-Phenotypic Cells: Are They Cousins or Twins? Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:716–29. doi: 10.3390/cancers30100716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Denderen BJ, Thompson EW. Cancer: The to and fro of tumour spread. Nature. 2013;493:487–8. doi: 10.1038/493487a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marjanovic ND, Weinberg RA, Chaffer CL. Cell plasticity and heterogeneity in cancer. Clin Chem. 2013;59:168–79. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.184655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kupferman ME, Jiffar T, El-Naggar A, Yilmaz T, Zhou G, Xie T, et al. TrkB induces EMT and has a key role in invasion of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:2047–59. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smit MA, Geiger TR, Song JY, Gitelman I, Peeper DS. A Twist-Snail axis critical for TrkB-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like transformation, anoikis resistance, and metastasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3722–37. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01164-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desmet CJ, Peeper DS. The neurotrophic receptor TrkB: a drug target in anti-cancer therapy? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:755–9. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5490-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geiger TR, Peeper DS. Critical role for TrkB kinase function in anoikis suppression, tumorigenesis, and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6221–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smit MA, Peeper DS. Zeb1 is required for TrkB-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition, anoikis resistance and metastasis. Oncogene. 2011;30:3735–44. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howe EN, Cochrane DR, Richer JK. Targets of miR-200c mediate suppression of cell motility and anoikis resistance. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R45. doi: 10.1186/bcr2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brabletz T. EMT and MET in metastasis: where are the cancer stem cells? Cancer Cell. 2012;22:699–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.