Abstract

The current study explores the intersection of ethnic identity development and significance in a sample of 354 diverse adolescents (mean age 14). Adolescents completed surveys 5 times a day for 1 week. Cluster analyses revealed 4 identity clusters: diffused, foreclosed, moratorium, achieved. Achieved adolescents reported the highest levels of identity salience across situations, followed by moratorium adolescents. Achieved and moratorium adolescents also reported a positive association between identity salience and private regard. For foreclosed and achieved adolescents reporting low levels of centrality, identity salience was associated with lower private regard. For foreclosed and achieved adolescents reporting high levels of centrality, identity salience was associated with higher private regard.

Empirical interest in ethnic identity has grown substantially in the past few decades. Despite the increased attention to the topic, there remain divergent approaches to its study. Some scholars approach the study of ethnic identity from an Erikson developmental perspective, employing statuses to track changes in identity processes over time (Phinney, 1989). Others are more focused on the content of ethnic identity, including the significance and meaning of ethnic identity at given point in time (Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997). While both approaches have contributed significantly to our understanding of how important it is to consider ethnic identity among adolescents, the two approaches have existed largely in parallel. Moving forward, in order to advance the study of ethnic identity, it seems important to integrate our understanding of how ethnic identity unfolds over time with our understanding of what it means to adolescents. Indeed, leading scholars in the field have long recognized the synergy between the two perspectives (Chatman, Eccles, & Malanchuk, 2005; Phinney, 1992; Sellers, et al., 1997), such that identity developmental status can be considered as a lens through which identity content is experienced on a daily basis (Syed & Azmitia, 2008). Despite the potential gain from empirically integrating developmental perspectives with ones that focus more on identity content, there are only a few recent examples of research that has done so.

The current study addresses this gap by integrating developmental theories of how ethnic identity changes over the life course with the immediate content of ethnic identity as adolescents move through their natural environments. For example, the notion of “salience” measures the relevance of ethnic identity at a particular point in time as a function of the interaction between a person’s cross-situationally stable characteristics (in this case, ethnic identity status) and the immediate environment (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998). The current study seeks to combine knowledge about the developmental process of an adolescent’s ethnic identity (i.e., identity status) with the content and significance of that identity across situations. Moreover, the current study seeks to explore how positively adolescents feel about their ethnic identity in situations where their ethnic identity is more or less salient and to see if this association might differ depending upon one’s ethnic identity status. Finally, the current study also seeks to explore whether this same association might exist between ethnic identity salience and general positive mood.

Scholars have long acknowledged the importance of integrating process and content approaches, since the two are conceptually distinct, yet functionally related (Phinney, 1989, 1993; Sellers, et al., 1997). For example, process and content likely share a reciprocal association such that salience is a necessary component of the developmental process, which in turn, informs the formation of content. In order to facilitate this integration, the current study poses three, interrelated research questions in a diverse sample of adolescents. First, how is an adolescent’s ethnic identity developmental status related to his/her experience of ethnic identity content on a daily basis? Specifically, how is identity status related to how salient ethnic identity is across naturally-occurring situations? Next, the current study explores the psychological consequence of ethnic identity salience and how it relates to identity status. For example, are adolescents who are further along in their ethnic identity development (i.e., process) more likely to feel good about their ethnic identity (i.e., content) when that identity is salient? Finally, the current study explores how an adolescent’s ethnic identity developmental status might interact with the centrality of that identity to influence feelings about group membership when ethnic identity is salient. In other words, do adolescents who are further along in their ethnic identity development (i.e., process), and who make ethnicity central to their identity (i.e., content), feel better about their identity when it is salient compared to adolescents who may be in the same ethnic identity development status (i.e., process) and who decide that ethnicity is not central to their identity (i.e., content)? In the following sections, the literature on process and content approaches to the study of ethnic identity are reviewed, followed by in integration of the two perspectives to highlight new areas of knowledge that can arise.

Process approaches to the study of ethnic identity: Theories and links to psychological adjustment

Theoretical models based on Erikson’s ego identity development and measures based on Marcia’s and Phinney’s (1992) scholarship have made significant contributions to the current literature on ethnic identity. Process is defined as “the way in which individuals come to understand the implications of their ethnicity and make decisions about its role in their lives” (Phinney, 1993, p. 64). Erikson’s theory (1968) suggests that beginning in adolescence, individuals progress through a sequence of identity statuses ranging from low to high levels of identity exploration and commitment. Exploration is defined as the extent to which an individual actively seeks information about his/her ethnic group. Commitment is considered to be the extent to which the individual has come to terms with the role of ethnicity in his/her life. The combination of low to high levels of identity exploration and commitment yield four identity statuses used to chart the progression of identity change over time. The developmental sequence includes a diffused status in which individuals have neither explored nor committed to an identity. The foreclosed status is characterized by committing to an identity but not undergoing extensive exploration or search. Moratorium status includes having explored an identity but not committing to it. Finally, an identity is considered achieved once an individual has both undergone an extensive period of exploration and committed to making that identity important to one’s self-construal (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1966). Although the original theory suggests an inherent sequence in the movement from one status to the next, recent revisions of the identity development models have allowed for individuals to move from one status to the next without specifying a prescribed developmental trajectory (Parham, 1989).

Applied to the study of ethnic identity development, recent research has lent empirical support to the existence of identity statuses (Syed & Azmitia, 2008). Using cluster analytic methods, Seaton et al. (Seaton, Scottham, & Sellers, 2006) found support for the diffused, foreclosed, moratorium, and achieved ethnic identity statuses in a sample of African American adolescents. Similar methods were employed to observe the same identity statuses in a sample of African American adolescents, young adults and adults (Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2006). Importantly, with a sample including adolescents (ages 13–17) through adults (ages 18–78), the study was able to examine if there was support for the theorized developmental sequence in identity statuses by exploring differences in identity status membership according to age. Indeed, the study found that adolescents were more likely to report being in the moratorium status and less likely to be achieved compared to young adults and adults. In addition, young adults and adults were more likely to be in the achieved status compared to diffused, foreclosed or moratorium. Thus, using cross-sectional data, there is preliminary support for an underlying developmental progression through the identity statuses.

Importantly, not only does Erikson’s theory outline the existence of identity statuses, but the theory also provides guidelines for how these statuses should relate to psychological adjustment. Specifically, achieved identities have been theorized to be associated with the highest level of psychological adjustment with diffused identities reporting the lowest levels, and moratorium and foreclosed identities falling somewhere in between. Indeed, empirical support is available for this hypothesis. Among African American adolescents, achieved youth reported fewer depressive symptoms and higher well-being compared to diffused youth and foreclosed youth reported fewer symptoms and higher well-being than diffused and moratorium youth (Seaton, et al., 2006). Similar patterns were observed in a study including adolescents, young adults and adults where young adults who were diffused reported higher levels of depressive symptoms compared to those reporting achieved identities (Yip, et al., 2006). The scant research that does exist on the topic seems to align with Erikson’s original theories of how identity statuses should be related to psychological adjustment. Despite evidence to suggest that identity statuses have predictable associations with general psychological adjustment, and that an achieved identity confers positive psychological benefits between persons (i.e., comparing one person to another), it is unclear whether these benefits also exist within persons (i.e., comparing one person to him/herself over time). In other words, how is having an achieved identity related to how adolescents feel about themselves from one situation to the next?

To address this gap in the literature, the current study examines whether adolescents with more advanced ethnic identities (i.e., relatively high levels of exploration and commitment) are more likely to think about their ethnic identity across situations. Adolescents who have spent time thinking about and deciding that ethnicity is a part of their identity may be more likely to think about that identity on a daily basis. And if so, do these same adolescents feel better about their ethnic identity when it is salient? In other words, are achieved adolescents more likely to feel good about themselves when they are thinking about their ethnic identity? First, the current study seeks to determine if the positive benefits that have been observed for achieved individuals exist at the level of the specific situation. Second, the current study explores whether the positive benefits of having an achieved identity extend beyond the observed effects for general psychological well-being to ethnic-specific positive feelings.

Content approaches to the study of ethnic identity: Theories and links to psychological adjustment

Rather than outlining a developmental sequence, another line of research on ethnic identity has focused on the content, meaning, and significance of ethnic identity at a given point in time. Ethnic identity content has been defined as “the actual ethnic behaviors that individuals practice, along with their attitudes toward their ethnic group” (Phinney, 1993, p. 64). In focusing on the meaning and significance of ethnic identity, the current study focuses on the latter dimension of content. Based on the African American experience, Sellers and colleagues developed the MMRI to theorize the multidimentionality of ethnic identity content (Sellers, Smith, et al., 1998). There are 2 primary components of the MMRI: significance and meaning. The current study will focus on the significance component which includes: centrality, salience, and regard. Centrality is a situationally-stable construct that measures how primary ethnicity is to one’s overall sense of self. Its complement, salience, is situationally-variable and measures how relevant ethnicity is at a specific moment in time. Salience is a function of the on-line interaction between centrality and the immediate setting characteristics. Regard captures feelings about one’s ethnic group membership, including private and public dimensions. Private regard measures an individual’s own feelings of positivity about his/her ethnic group membership. Public regard captures how individuals think that others view their ethnic group. The MIBI operationalizes all dimensions of the MMRI (Sellers, et al., 1997), with the exception of salience.

Unlike the process approach, the content approach does not specify a priori associations between ethnic identity and psychological adjustment; instead the association between identity and outcomes depends upon which dimension of ethnic identity one is interested in. For example, one might not expect to find a positive association between centrality and self-esteem since an individual’s feelings of self-worth could be grounded in other social identities (e.g., gender, occupation). Indeed, empirical studies do not find a direct link between the two (Rowley, Sellers, Chavous, & Smith, 1998). Focusing on private regard, however, one would expect that an individual’s positive evaluation of his/her ethnic group would have a positive association with one’s overall sense of self-worth, particularly if that identity is central to the individual’s self-definition. And in fact, research supports this contention; ethnic centrality interacts with feelings of private regard such that individuals who report that ethnicity is central to their self-concept report a stronger positive association between private regard and self-esteem (Rowley, et al., 1998). Hence, centrality, or the importance of ethnicity to one’s overall identity, in combination with other indices of ethnic identity (i.e., developmental status) may provide additional insight into psychological well-being.

The current paper seeks to focus on how the salience, centrality and private regard dimensions of the MMRI might be related to identity development status. In addition, how process and content may come together to influence psychological well-being and positive feelings specific to ethnicity is explored. In particular, the study examines how centrality might interact with an adolescents’ ethnic identity developmental status to influence how the adolescent feels about his/her ethnic identity (private regard) when that identity is salient. Consistent with existing research, it is expected that adolescents reporting achieved identities and high levels of centrality should predict stronger psychological benefits when identity is salient. Finally, how centrality and development status might interact to influence general feelings of positive mood is also explored.

Integrating process and content approaches to the study of ethnic identity: Theories and links to psychological adjustment

Scholars, whether taking a process or a content perspective, have acknowledged the importance of integrating the two approaches (Phinney, 1989; Sellers, et al., 1997). In service of this goal, recent research has begun to take an integrative approach. In a diverse sample of college students, Syed and Azmitia (2008) also recreate identity development statuses employing exploration and commitment measures and find a link between process and content. Specifically, employing a narrative approach, the authors assessed content through interviews geared towards asking participants to recall “self-defining” memories. The results of the study found that the group reporting low levels of exploration and commitment were more likely to recall memories where their ethnic group was different or under-represented. In contrast, the moratorium and achieved identity clusters reported much less frequent encounters with such memories. Finally, young adults reporting an achieved identity status were also mostly likely to report feeling connected to their cultural group. In addition, researchers have found that individuals (ranging from adolescents to adults) who report an achieved identity, also report higher levels of centrality (Syed & Azmitia, 2008) and private regard (Syed & Azmitia, 2008; Yip, et al., 2006) compared to other identity development configurations. Hence, it is clear that centrality has some association with identity status, but what are the day-to-day consequences of this association? The current study attempts to fill an important gap in the field by exploring the association between ethnic identity process and content within a person, across situations. As such, the study addresses three interrelated research goals.

The first goal of this paper is to examine possible differences in situation-level experiences of salience according to identity development status. According to the process approach, ethnic identity achievement is theorized to indicate that an adolescent has explored the significance and meaning of ethnicity as well as committed to its importance in one’s overall sense of self. According to the content approach, identities that are important, are more central, and individuals with higher levels of centrality are also more likely to find that their ethnicities are more likely to become salient across everyday situations. Therefore, the integration of process and content approaches would predict that adolescents who report relatively higher levels of exploration and commitment would also report that their ethnic identity is more salient across situations. While there is evidence to suggest that individuals with higher levels of exploration and commitment also report higher levels of centrality (Yip, et al., 2006), there is no research examining how identity status might be related to salience across situations. How does where an adolescent is in his/her ethnic identity development, influence how often ethnic identity is salient across situations? Based on existing research, adolescents who report more advanced ethnic identity statuses (i.e., relatively high levels of exploration and/or commitment) are hypothesized to report that their identity is more salient across situations. Similarly, adolescents reporting less advanced ethnic identity statuses (i.e., relatively low levels of exploration and commitment) are expected to report that identity is less salience across situations. The foreclosed and moratorium clusters are often characterized as intermediary points between diffused and achieved identities (Phinney & Ong, 2007), they are expected to report levels of identity salience that fall somewhere between those reported by diffused and achieved adolescents, but do not have a priori hypotheses about differences between these two identity configurations.

In addition to ethnic identity being more salient across situations, adolescents with more advanced ethnic identity statuses (i.e., relatively high levels of exploration and/or commitment) are hypothesized to report feeling better about their ethnic identity (i.e., private regard) when ethnic identity is salient. To test the second goal of the study, differences in the situation-level association between salience and psychological adjustment by identity development status are explored. Moreover, the study differentiates non-specific positive feelings (i.e., general positive mood) from positive feelings that result from one’s ethnic identity (i.e., private regard). Process approaches theorize that with identity achievement, an adolescent has some resolution around the role of ethnicity and with that resolution comes a general positivity about oneself. Similarly, in the content approach, although centrality and private regard are conceptualized and measured as separate constructs, they are related such that an adolescent who chooses to make ethnicity central to his/her identity likely feels positively towards that identity (Sellers, Smith, et al., 1998). Indeed, empirical work consistently finds a positive association between centrality and private regard (e.g., Byrd & Chavous, 2011; Rowley, et al., 1998). Although related to centrality, less work has focused on the association between salience and private regard for individuals differing on levels of identity achievement. However, given theories linking identity achievement to more positive psychological outcomes (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1966; Meeus, Iedemaa, Helsen, & Vollebergh, 1999), adolescents who report higher levels of exploration and commitment are hypothesizes to report stronger positive associations between salience and private regard. In other words, when ethnic identity is salient, adolescents with achieved identities should report feeling better about being a member of their ethnic group. It is predicted that there will be no association between salience and private regard for adolescents reporting a diffused identity, and moderate associations for adolescents in the foreclosed and moratorium statuses. Consistent with existing research (Bracey, Bamaca, & Umana-Taylor, 2004; Phinney, 1991), similar associations between salience and non-specific positive mood are also predicted.

Finally, the current study will examine how process and content come together to influence how an adolescent feels about his/her ethnic identity when it is salient. Specifically, how identity achievement status interacts with levels of centrality to predict the situation-level association between salience and private regard is explored. Because of the positive psychological benefits conferred to having an achieved ethnic identity, adolescents with more advanced ethnic identity statuses (i.e., relatively high levels of exploration and/or commitment) and who have high levels of centrality, are hypothesized to report higher levels of private regard when their ethnic identity is salient. For adolescents reporting foreclosed or moratorium identity statuses, high levels of centrality may confer positive psychological benefits of ethnic identity salience. Similarly, the positive benefits of identity status and centrality are expected to hold true for non-specific positive mood.

Method

Participants

Adolescents were recruited from 5 New York City public high schools. Schools were chosen to represent varying degrees of racial/ethnic composition including: a predominantly Asian, predominantly Latino, predominantly White and 2 racially heterogeneous schools. Once schools were selected, all 9th grade students were invited to participate in the study. The sample includes 354 adolescents ranging in age from 13–16 years old (M = 14.18, SD = .46). The sample is diverse; using self-report measures, the sample includes 1% American Indian, 12% African American, 25% Hispanic/Latino, 34% Asian and 23% White. The sample represents a roughly equal distribution of adolescents selected from the 5 schools with approximately 20% of the sample selected from each school. Females are over-represented in the sample (63%). The sample is predominantly United States-born (82%) with those who were not born in the United States coming from countries such as China, Poland, Bangladesh, Columbia, Ecuador and the Philippines. Forty percent of the sample reported that they did not know their father’s highest level of education completed, with the next most frequent response being high school (17%), followed by 4-year college (10%). As for mother’s highest level of education completed, 34% of students reported not knowing, followed by 16% reporting high school and 13% reporting 4-year college educations. Based on Census track information, on average adolescents reported living in neighborhoods in which 17% of families lived below the poverty line with the modal response recorded as 15% of families reporting incomes between $50–$75,000.

Procedure

Groups of participants ranging in size from 5–25 students met with a research team to complete paper and pencil demographic surveys and measures of ethnic identity. Next, for the experience sampling portion of the study, participants were given cellular phones and instructed to complete a brief 2–3 minute online survey using the cellular phones’ browser each time the phone prompted the participant. To familiarize participants with the protocol, the research team demonstrated how to complete surveys on the phones and participants completed a sample survey in the presence of the research team. The cellular phones were programmed to prompt participants 5 times a day starting in the afternoon when participants were dismissed from school and throughout the evening until 10pm. Participants were unaware of when the cellular phones were programmed for prompts. Participants completed these experience sampling reports 5 times a day for 7 days. At the end of the week, researchers administered another paper and pencil survey including ethnic identity measures and collected the cellular phones. Participants were compensated $50 for their time.

To encourage compliance, participants who completed 100% of their experience sampling reports were entered into a raffle to win an additional $100. Because the cellular phones prompted participants at times that were not known to the participant, and participants completed surveys in natural settings (i.e., sports training, music lesson, doctor’s appointment) missing data could not be avoided. Compliance for the study is estimated to be 3.99 surveys per day (range 0 – 5).

Measures

Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure

Consistent with existing research exploring the role of identity achievement statuses, to operationalize developmental statuses, the current study focused on the exploration and commitment subscales of the MEIM (Roberts et al., 1999). Exploration includes 5 items and assesses the extent to which an adolescent has actively examined the role of ethnicity in his/her identity, for example, “I have spent time trying to find out more about my own ethnic group, such as history, traditions, and customs”. The response scale ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree (M = 2.61, SD = .54, α = .74). Commitment includes 7 items and taps into a sense of resolution around the role of ethnicity in one’s life, for example, “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means to me” (M = 2.97, SD = .44, α = .87). Because the sample included adolescents from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, it was important to establish measurement invariance between the White and the adolescents of color. Comparing an unconstrained model to a constrained weights model taking into account White and adolescents of color, the differences in the χ2 between the two models was not significantly different (Δ χ2 = 19.46, Δ df = 21), suggesting that that adding the constraints and taking into account the 2 groups did not worsen the fit of the model.

Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity

To operationalize the content of ethnic identity, the MIBI (Sellers, et al., 1997) was adapted for use with a multi-ethnic population by replacing “Black” in the original scale with “my race/ethnicity”. For example, centrality, which includes 7 items and measures the relative importance of ethnicity to one’s overall identity, for example, “My race/ethnicity is an important reflection of who I am”. The response scale ranges from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree (M = 4.23, SD = .93, α = .70). The study also includes private regard, which includes 7 items and taps an individual’s feeling about his/her ethnic group membership, such as “I am happy that I am a member of my racial/ethnic group” (M = 5.22, SD = .89, α = .71). Tests of measurement invariance suggested that there were no measurement differences between the White adolescents and the adolescents of color. Comparing an unconstrained model to a constrained weights model taking into account White and adolescents of color, the differences in the χ2 between the two models was not significantly different (Δ χ2 = 5.31, Δ df = 21), suggesting that that adding the constraints and taking into account the 2 groups did not worsen the fit of the model.

Situation-level Salience

Situation-level salience may operate with or without a person’s awareness (Sellers et al., 1998). Because the current study relies on self-report measures, salience is operationalized as one’s awareness of his/her ethnic identity. At each prompt on the cellular phones, adolescents were asked to respond to a set of questions about their immediate experiences in their current context, including the salience of his/her ethnic identity at that specific moment in time. Respondents completed a single item indicating “How aware are you of your race/ethnicity right now” on a scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 7 = extremely (M = 4.27, SD = 2.09). To deflect attention away from race/ethnicity, participants also responded to questions about the salience of 5 other social identities including: age, gender, national identity, friend and student.

Situation-level Private Regard

To assess daily ethnic private regard, the MIBI-S private regard scale was adapted for how participants felt in a specific situation (Martin, Wout, Nguyen, Sellers, & Gonzalez, 2005). Participants completed two items (e.g., “I was happy that I am my race/ethnicity” (M = 3.72, SD = 1.53, r = .70).

Situation-level Positive Mood

To assess non-specific positive mood, 4 items were employed (i.e., happy, calm, joyful, excited). At each prompt, adolescents indicated the extent to which each item described their feelings “right now” ranging from 1 = “not at all” to 5 “extremely” (M = 4.20, SD = 1.40, r = .84).

Results

Although this is not the first study to include the conceptually distinct, yet likely related, constructs of identity commitment and centrality, it was important to establish that the two were independent constructs. As such, a confirmatory factor analyses was conducted including the 7 commitment items and the 7 centrality items. The results suggested that a 2-factor model fit better than a 1-factor model and that each of the commitment and centrality items loaded on to their respective scales (Δ χ2 = 132.26, df = 1, p < .01, RMSEA = .80, CFI = .90).

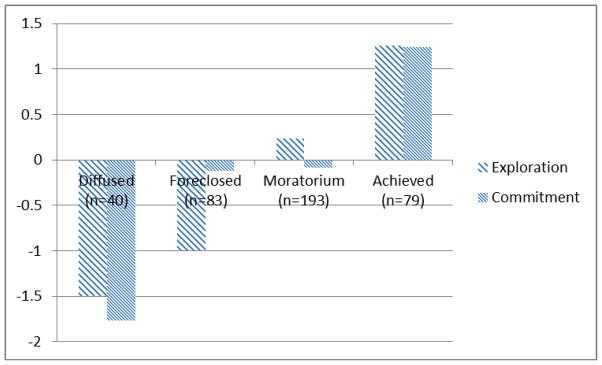

Consistent with existing research that has operationalized identity development statuses (Seaton, et al., 2006; Syed & Azmitia, 2008), to create the identity achievement statuses, standardized exploration and commitment scores on the MEIM were included in cluster analyses. Because theory and previous empirical research finds evidence for 4 distinct clusters, KMeans analyses were conducted to identify the 4 identity statuses. To validate the clusters extracted using the KMeans method, a Monte Carlo procedure was used where a 50% subset of the sample was randomly selected, and the KMeans cluster technique was repeated on this subset (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). Cluster membership for this subset was compared with the initial membership in the full sample. This procedure was repeated twice and the cluster memberships for the subset and full sample were consistent 84% of the time.

The four-cluster solution is theoretically and empirically consistent with previous research (Marcia, 1966; Seaton, et al., 2006; Yip, et al., 2006). A cluster consistent with a diffused identity (i.e., low exploration, low commitment), was the smallest of the 4 clusters (N = 40; Figure 1). A cluster mapping on to a foreclosed status (marked by low levels of exploration and moderate levels of commitment) was identified (n = 83). The largest cluster consisted of a moratorium group with above average levels of exploration and moderate levels of commitment (n = 193). Finally, a cluster consistent with an achieved identity (i.e., high exploration, high commitment; n = 79) was also extracted. While the foreclosed and moratorium clusters have similar levels of commitment, their difference seems to be characterized by levels of exploration with the foreclosed cluster reporting markedly lower levels. Therefore, the clusters are largely consistent with theorized statuses and consistent with existing empirical work using different samples across different age groups.

Figure 1.

Ethnic identity development statuses

Correlations among the key study variables indicate that all variables (i.e., exploration, commitment, centrality, private regard, situation-level awareness of salience, situation-level private regard and situation-level positive mood) were significantly positively associated with each other with the exception of centrality and positive mood (Table 1). For situation-level variables of ethnic identity awareness of salience, private regard and positive mood, situation-level data were averaged across each person.

Table 1.

Correlations Among Key Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exploration | -- | .58** | .45** | .35** | .26** | .21** | .16** |

| 2. Commitment | -- | .40** | .52** | .37** | .26** | .12* | |

| 3. Centrality | -- | .32** | .31** | .19** | .10 | ||

| 4. Private Regard | -- | .40** | .21** | .15** | |||

| 5. Mean of Situation-level Identity Awareness of Salience | -- | .42** | .22** | ||||

| 6. Mean of Situation-level Private Regard | -- | .14** | |||||

| 7. Mean of Positive Mood | -- |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Data Analyses Overview

Due to the nested nature of these data, the study hypotheses were tested using Hierarchical Linear Models (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992) which accounts for how situations are nested within adolescents and adolescents are nested within schools. HLM allows for simultaneous analyses at more than one level. In this case, situations are considered to be Level 1, adolescent characteristics are modeled at Level 2, and possible school effects are modeled at Level 3. In all analyses, beep (1–5) and day of the study (1–7) were adjusted for in the Level 1 model. Since beep and day of study were observed to influence the situation-level outcomes, they are retained in the models presented here. Possible effects of gender (male versus female), nativity status (foreign- versus US-born), and ethnicity (American Indian, Black, Hispanic, Asian, White) were adjusted for all models at Level 2, however, no significant effects were observed; for ease of presentation, these variables are omitted from the models presented here.

To address the first goal of the study, the extent to which adolescents who report more advanced identity statuses (i.e., higher levels of exploration and/or commitment) would also be more likely to report that their ethnic identity is salient across situations was explored. To test this hypothesis, ethnic identity awareness of salience at the level of the specific situation (Level 1) was estimated as the outcome and cluster membership (Level 2) as the predictor. Dummy variables were created to represent each of the 4 identity statuses, with the diffused cluster serving as the reference group. Since there were possible school-level effects, the analyses included nesting effects at Level 3.

- Level 1 (Situation level):

- Level 2 (Individual level):

- Level 3 (School level):

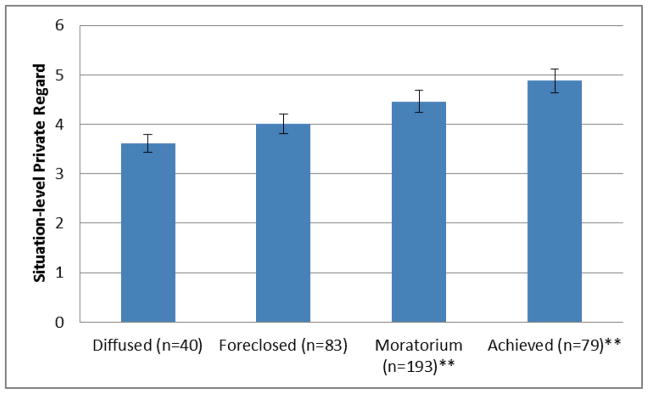

Results from the HLM analyses suggest that there were differences in levels of ethnic identity awareness of salience across situations such that adolescents in the moratorium (b = .84, SE = .28, p < .01; Figure 2) and achieved (b = 1.26, SE = .31, p < .01; Figure 2) statuses (both characterized by above-average levels of exploration) reported higher ethnic identity awareness of salience compared to adolescents in the diffused cluster. To explore whether the observed differences between the moratorium and achieved identity clusters were significantly different from each other, another analysis was conducted using the achieved group as the reference group. Results suggest that the moratorium cluster reported significantly lower levels of ethnic identity awareness of salience across situations compared to the achieved identity cluster (b = −0.48, SE = .22, p < .05). Consistent with hypotheses, adolescents who were in the moratorium or achieved identity statuses reported higher ethnic identity awareness of salience across situations compared to adolescents who reported a diffused identity status. There were no differences observed between the foreclosed and the diffused clusters.

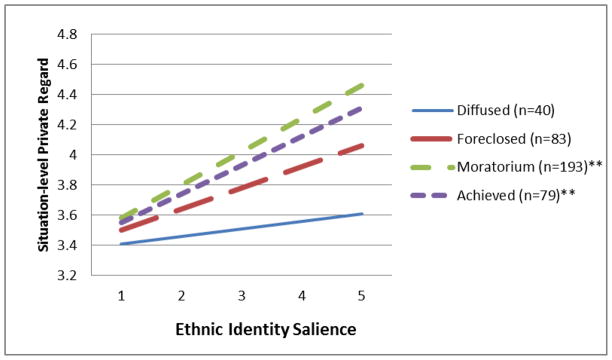

Figure 2.

Differences in situation-level private regard by ethnic identity status

Note: Moratorium > Diffused, Achieved > Moratorium.

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Next, the study examined potential differences in feelings of private regard, when ethnic identity is salient, and if this association might differ by identity achievement status. This analysis builds off the previous models by replacing the Level 1 outcome with situation-level private regard and including situation-level ethnic identity awareness of salience as a predictor. As with the previous analysis, the identity status clusters are included at Level 2 as potential moderators of the intercept (average levels of awareness of salience) and the association between awareness of salience and private regard. Stable private regard is also included at Level 2 to adjust for possible effects of stable private regard on situation-level private regard. The Level 3 model remains unchanged from previous analyses.

- Level 1 (Situation level):

- Level 2 (Individual level):

Consistent with the previous analysis and with hypotheses, the moratorium and achieved identity clusters reported significantly different patterns compared to adolescents in the diffused cluster (Table 2). Specifically, adolescents who reported moratorium (b = .15, SE = .05, p < .01; Figure 3) or achieved (b = .15, SE = .06, p < .01; Figure 3) identities reported positive associations between ethnic identity awareness of salience and private regard compared to the diffused cluster. In other words, for adolescents in the moratorium or achieved identity clusters, when ethnic identity was salient in a situation, adolescents also reported feeling better about being a member of their ethnic group. Unlike the previous set of analyses, there were no significant differences between the moratorium and achieved identity clusters. As before, no significant effects were observed for adolescents in the foreclosed identity status.

Table 2.

HLM Estimates of Private Regard as Predicted by Ethnic Identity Awareness of Salience and Moderated by Identity Status

| B | SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Situation-level Private Regard (L1) | B00, G000 | 3.19*** | 0.19 |

| Stable Private Regard (L2) | B01, G010 | 0.58*** | 0.06 |

| Foreclosed Dummy (L2) | B02, G020 | 0.85*** | 0.19 |

| Moratorium Dummy (L2) | B03, G030 | 0.87*** | 0.18 |

| Achieved Dummy (L2) | B04, G040 | 1.48*** | 0.20 |

| Situation-level Ethnic Identity | B10, G100 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Awareness of Salience (L1) | |||

| Stable Private Regard (L2) | B11, G110 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Foreclosed Dummy (L2) | B12, G120 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Moratorium Dummy (L2) | B13, G130 | 0.15** | 0.05 |

| Achieved Dummy (L2) | B14, G140 | 0.15* | 0.06 |

| Day of Study (L1) | B20, G200 | −0.05*** | 0.00 |

| Beep (L1) | B30, G300 | −0.02** | 0.01 |

Note: Diffused status serves as the reference group.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 3.

Differences by ethnic identity status in the situation-level association between ethnic identity salience and private regard

Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

As a related goal, the study explores whether the positive benefits of awareness of salience were isolated to ethnicity-related feelings of private regard or whether the benefits would generalize to overall positive feelings. In service of this goal, parallel analyses were conducted with positive mood as the outcome, replacing private regard. Surprisingly, these analyses suggested that there is no association between awareness of salience and general positive mood, regardless of identity achievement status. Therefore, it seems that the data patterns observe describe a unique association between ethnic identity awareness of salience and ethnicity-related feelings of positivity.

Finally, to address the third goal of the study, examining whether centrality might interact with identity achievement status to influence the association between ethnic identity awareness of salience and private regard, a potential interaction between stable centrality and identity cluster at Level 2 was included. The Level 1 and 3 models remain unchanged.

- Level 2 (Individual level):

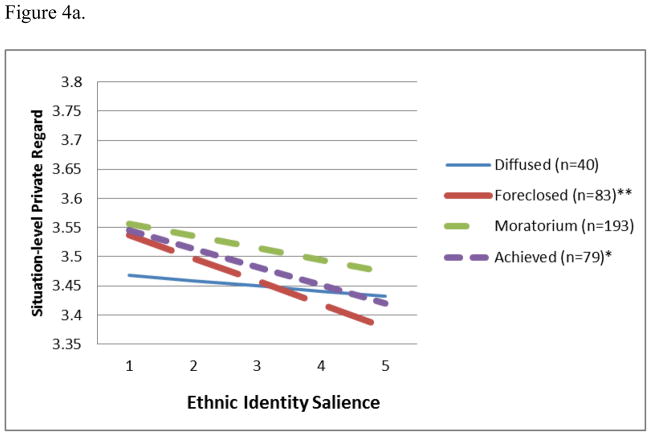

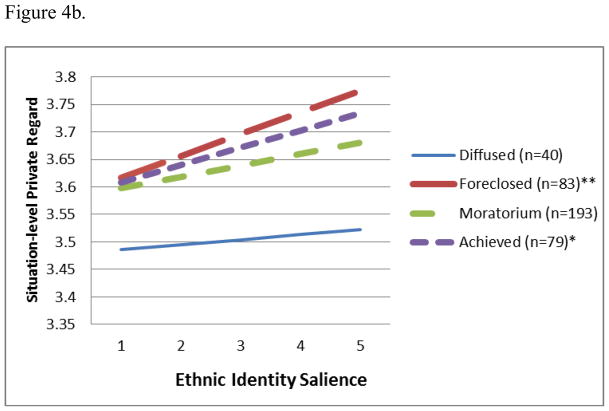

Consistent with hypotheses, the results suggest that there was an interaction between centrality and identity status cluster for the foreclosed and achieved adolescents (Table 3). Specifically, for adolescents in the foreclosed identity status, who also reported low levels of centrality, there was a strong negative association between ethnic identity awareness of salience and private regard (Figure 4a). In other words, for adolescents who reported particularly low levels of exploration and moderate levels of commitment, those who reported that their ethnicity was not central to their identity also reported less positivity about belonging to their ethnic group when their identity was salient. A similar pattern was observed for adolescents reporting an achieved identity, characterized by high levels of exploration and commitment. In contrast, among adolescents reporting high levels of centrality, foreclosed and achieved adolescents reported a positive association between awareness of salience and private regard such that as ethnic identity awareness of salience increased, so did feelings of private regard (Figure 4b). Adolescents in the diffused and moratorium statuses did not report differences in the association between awareness of salience and private regard according to centrality.

Table 3.

HLM Estimates of Private Regard as Predicted by Ethnic Identity Awareness of Salience and Moderated by Identity Status and Centrality

| B | SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Situation-level Private Regard (L1) | B00, G000 | 3.48** | 0.23 |

| Stable Centrality (L2) | B01, G010 | 0.35* | 0.16 |

| Stable Private Regard (L2) | B02, G020 | 0.50*** | 0.07 |

| Foreclosed Dummy (L2) | B03, G030 | 1.55* | 0.76 |

| Moratorium Dummy (L2) | B04, G040 | 0.76 | 0.68 |

| Achieved Dummy (L2) | B05, G050 | 2.31** | 0.87 |

| Centrality x Foreclosed (L2) | B06, G060 | −0.22 | 0.20 |

| Centrality x Moratorium (L2) | B07, G070 | −0.04 | 0.18 |

| Centrality x Achieved (L2) | B08, G080 | −0.26 | 0.21 |

| Situation-level Ethnic Identity | B10, G100 | 0.10** | 0.03 |

| Awareness of Salience (L1) | |||

| Stable Centrality (L2) | B11, G110 | 0.09** | 0.03 |

| Stable Private Regard (L2) | B12, G120 | −0.03** | 0.01 |

| Foreclosed Dummy (L2) | B13, G130 | 0.44** | 0.12 |

| Moratorium Dummy (L2) | B14, G140 | 0.23* | 0.11 |

| Achieved Dummy (L2) | B15, G150 | 0.35* | 0.14 |

| Centrality x Foreclosed (L2) | B16, G160 | −0.11** | 0.03 |

| Centrality x Moratorium (L2) | B17, G170 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Centrality x Achieved (L2) | B18, G180 | −0.07* | 0.03 |

| Day of Study (L1) | B20, G200 | −0.06** | 0.00 |

| Beep (L1) | B30, G300 | −0.01* | 0.01 |

Note: Diffused status serves as the reference group.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 4.

Figure 4a. Interaction of identity status and centrality moderating the situation-level association between ethnic identity awareness of salience and private regard - Low Centrality Adolescents

Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Figure 4b. Interaction of identity status and centrality moderating the situation-level association between ethnic identity awareness of salience and private regard - High Centrality Adolescents

Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

As before, to explore whether these associations were specific to ethnicity, parallel analyses replacing private regard as the outcome with general positive mood were conducted. Again, contrary to hypotheses, no significant associations were observed between awareness of salience, according to identity achievement status, centrality, nor their interaction. Taken together, it seems that the observed effects are unique to positive feelings related to ethnicity.

Discussion

The current study attempts to bridge two, largely parallel, literatures on ethnic identity among adolescents. In particular, employing sample of diverse, urban adolescents, the study explores how where they are in their ethnic identity development influences how they experience that identity on a daily basis. Consistent with existing research that has attempted to integrate these literatures, robust and expected associations between identity development and content were observed. Namely, in general, adolescents who represent the more “advanced” identity development status, as marked by higher levels of exploration and commitment, reported having higher ethnic identity awareness of salience across situations. Moreover, these same adolescents also tend to report feeling better about their ethnic group membership, as measured by private regard, when their ethnic identity is salient. Finally, the current study observes a further interaction between identity development status and centrality such that the effects of development are amplified for adolescents who also report that ethnicity is central to their identity. Taken together, this study highlights the new knowledge to be gained from integrating developmental process and identity content approaches to understanding the complexity with which ethnic identity impacts the everyday lives of youths in the United States.

To begin, the current study ventured to replicate previous work exploring support for the existence of the 4 identity statuses as outlined by Erikson (1968) and further elaborated by Marcia (1966) and Phinney (1992). While previous research has focused primarily on African American samples (Seaton, et al., 2006; Yip, et al., 2006), this study included a diverse, multi-ethnic and multi-racial sample of adolescents attending schools specifically selected to represent differing racial/ethnic compositions. Despite this difference, consistent with existing research, this study also found support for 4 identity development statuses. In the current sample, the means for exploration and commitment, which were used to create the identity statuses, were relatively high, above the midpoint on the response scale. As such, since the identity clusters were created using standardized scores, there were possible ceiling effects for how “high” adolescents could score relative to the mean. It is possible that this explains why the moratorium status, the largest of the four, was characterized by somewhat muted levels of exploration and commitment. That is, while the moratorium status was theoretically aligned with being “high” on exploration and “low” on commitment, the levels of “high” and “low” need to be interpreted relative to the sample. These data patterns may also represent a developmental phenomenon; recall that all participants were in the 9th grade, perhaps moderate levels of exploration and commitment represents a developmental norm for urban adolescents living in a diverse environment and attending diverse schools. While data has suggested that the presence of an out-group highlights intergroup differences (Rutland, Cameron, Bennett, & Ferrell, 2005), there may be a tipping point, after which, a certain level of ethnic diversity may influence identity exploration and commitment in the form of an inverted U-shape.

Following up on the discussion about developmental norms, the next largest group was the foreclosed status, which in theory is characterized by low levels of exploration and high levels of commitment. In the current sample, commitment levels were lower than theory would suggest, again perhaps due to possible ceiling effects in these data. The achieved status, characterized by high levels of exploration and commitment was the third largest group. This observation seems consistent with identity development theory (Erikson, 1968), where one would expect the representation in the achieved cluster to increase with an older sample (Yip, et al., 2006). Finally, the diffused status was the smallest of the four and represents adolescents who report particularly low levels of exploration and commitment. Given the age of the current sample (ages 13–16), theory would predict the presence of some, but not many, adolescents in this stage, particularly since the sample lives in a racially-diverse, urban area. If the sample were to be followed longitudinally into young adulthood and adulthood, one would predict that the number of individuals who report diffused identities would decline with age (Erikson, 1968).

Having replicated the identity statuses, the first goal of the study was to determine if identity development statuses were related to everyday experiences of ethnic identity awareness of salience across situations. Indeed, this study observed that adolescents in the moratorium and achieved statuses reported higher levels of ethnic identity awareness of salience, at the level of the situation, as compared to diffused and foreclosed adolescents. Common across the moratorium and achieved statuses, is above-average levels of exploration. Therefore, perhaps, awareness of salience serves as a mechanism through which adolescents explore their identities. Consistent with this hypothesis, the achieved status (which reports the highest level of exploration of the 4 statuses) reported the highest level of awareness of salience across situations, even when compared to moratorium. Taken together, it appears that adolescents who have either explored, or explored and committed to their identities to report an increased relevance in their ethnic identity across situations. Since these data are cross-sectional, it is not clear whether exploration alone, or in combination with commitment, begets awareness of salience or whether the opposite is true, but this is an area that is ripe for future research. What is clear is that there seems to be reliable associations between identity development status and adolescents’ everyday experiences of ethnic identity awareness of salience. Why would adolescents who have reported above-average levels of exploration be more likely to report that their ethnic identity is relevant across situations? It seems likely that the process of exploring an identity rendered that identity salient across various contexts and situations. As such, the adolescent who has explored an identity has also thought about that identity more than an adolescent who has not engaged in exploration. One way in which adolescents may have experienced more salient identities through identity exploration is through enacting that identity across contexts. Cross and Strauss (1998) discuss 5 ways in which identity is enacted across situations including: buffering, bonding, bridging, code-switching and individualism. All of these processes are likely to invoke identity awareness of salience and to be involved in identity exploration. For example, bonding involves forming connections with one’s ethnic group – a process likely involved in identity exploration and likely to invoke identity awareness of salience. Therefore, the data seem to suggest that once an adolescent has explored ethnicity as a component of identity, that process then renders identity more salient in the future.

The second, related goal of this study was to determine, what, if any, consequences accompany the awareness of salience of ethnic identity. In service of this goal, this study explored the situation-level association between ethnic identity awareness of salience and private regard, as well as with non-specific positive mood. Consistent with existing literature, while one would expect to find an association for both private regard and positive mood, however, the data only supported evidence for an association between ethnic identity awareness of salience and private regard. In particular, consistent with the results of the first goal of the study, it was only among adolescents who reported some level of exploration (i.e., moratorium and achieved) that this positive association was observed. For adolescents in the moratorium and achieved identity statuses, the more salient one’s ethnic identity, the more positive adolescents felt about being a member of his/her ethnic group. The data suggest that above-average levels of exploration, seem to be associated with feeling good about one’s ethnic group membership across situations, particularly when ethnic identity is salient. In light of these data, it seems possible that the decision to explore an identity is associated with positive feelings about that identity. In other words, for an adolescent to choose to explore an ethnic (as opposed to another social category) identity may mean that s/he already feels positively toward that group. This hypothesis is supported by research that finds a positive link between exploration and positive psychological outcomes (Umana-Taylor, Vargas-Chanes, Garcia, & Gonzales-Backen, 2008) (Umana-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009) however, additional longitudinal research is necessary.

Although the associations between awareness of salience and private regard were robust at the situation-level, notably, parallel associations between awareness of salience and non-specific feelings of general mood according to identity development statues were on observed. This observation seems in contrast to existing theory and research at the person-level suggesting that more achieved identities have been associated with better psychological outcomes (Erikson, 1968). Instead, at the level of the situation, awareness of salience is positively associated only with private regard and not non-specific positive feelings. While seemingly inconsistent with existing research, it seems possible that if awareness of salience and private regard are consistently paired in everyday situations, over time, the positive feelings associated with private regard would generalize to positive feelings about oneself overall. In other words, the repeated pairing of awareness of salience and private regard at the level of the situation may eventually lead to a pairing of an adolescent’s stable ethnic identity and general psychological health. This possible longitudinal association would explain the apparent inconsistency between the between-and within-person results.

In this vein, the final goal of this study explored whether centrality, an individual difference in how important ethnicity is to one’s overall identity, may interact with identity development status to influence the situation-level association between ethnic identity awareness of salience and psychological well-being. Since identity development processes and identity content are separate, but related constructs, it seemed possible that the two would come together to influence the psychological consequence of ethnic identity awareness of salience at the level of the situation. And indeed, the data support the notion that identity development status matters for identity experiences across situations. In particular, adolescents in the foreclosed and achieved statuses, report similar patterns where adolescents in both groups who also report that ethnicity is not central to their identity, report lower levels of private regard when ethnic identity is salient. In contrast, adolescents in the same identity development status reporting high levels of centrality, report a strong positive association between ethnic identity awareness of salience and private regard. Since the foreclosed and achieved statuses do not share common levels of exploration or commitment, but do report similar data patterns at the situation level, it is likely that different underlying processes are responsible for these effects. Among the low centrality adolescents reporting a foreclosed identity (low exploration and moderate commitment), identity awareness of salience was associated with marked decreases in private regard. Despite being in a diverse area, these adolescents have decided to minimize the role of ethnic identity in their identity. They have avoided developmental associations with exploration and commitment and have indicated that ethnicity is not central to how they live their lives. For such adolescents, the awareness of salience of ethnic identity is associated with feeling worse about that ethnic group membership. It is likely because these students have chosen to de-emphasize the role of ethnicity in their lives, when they are reminded of it, they feel bad about their group membership. In contrast, adolescents who have spent time exploring and committing to an ethnic identity (i.e., achieved) can also decide that it is not a defining component of their identity. For these adolescents, awareness of salience is also associated with lower private regard. Since these adolescents have undergone a process of exploration and commitment, they are clear that low centrality means that ethnicity is not a defining feature of their identity. When these adolescents are reminded of a component of their identity that they have decided is not central, they report feeling bad about their group membership – possibly because they have made the explicit decision to de-emphasize this component of their identity. When an identity that adolescents have decided not to make central becomes salient in a particular situation, it is a form of identity denial. There is a growing body of literature to show that identity denial has negative mental health implications (Cheryan & Monin, 2005; Huynh, Devos, & Smalarz, 2011; Kim, Wang, Deng, Alvarez, & Li, 2011), and the results here seem to bolster this claim.

While this study makes a significant contribution to the study of ethnic identity among adolescents, particularly in terms of integrating two largely parallel approaches to its study, it is not without limitations. Highlighting the limitations of the current study can help outline direction for future work. Sample-related limitations include the over-representation of female and United States-born adolescents. Also, the sample was selected from a large, urban area, precluding generalization to rural or suburban populations. Although the study includes intensive repeated measures, the cross-sectional nature of the data leave open the question of how identity development status and content are related over time. For example, it seems likely that there is a reciprocal association between process and content where developmental status serves as a lens through which content is perceived, and where content then subsequently shapes development. This area seems particularly ripe for future research since adolescents show evidence of movement between identity status from one year to the next (Seaton et al., 2006). This study also leaves unaddressed the situation-level context that leads to awareness of salience. For instance, identity can become salient due to positive interactions (e.g., celebrating ethnic holiday) or negative interactions (e.g., being the target of discrimination). Future research should focus on disentangling the valence of how ethnic identity becomes salient.

Before concluding, it is worth highlighting the diversity of the current sample. In addition to ethnic minorities, the current study also included 23% non-Hispanic white adolescents. Because the field of ethnic identity has historically focused on the former, the analyses presented here were conducted including and excluding the white subsample. Since no differences were observe between these two approaches, the current study presents the sample as a whole. In light of the racial ethnic diversity of New York City and because only 20% of the sample was selected from a predominantly White school, the results observed here may not generalize to other non-Hispanic populations. Finally, 18% of the non-Hispanic white adolescents in this current sample were not born in the United States, so that may account for some of the similarities with the ethnic minority sample.

In conclusion, this study attempts to bridge an important gap between developmental and content approaches to the study of ethnic identity. In doing so, the two perspectives are found to be related. Namely, adolescents reporting more advanced identity development statuses reported that their ethnic identity had more relevance and consequence in their daily lives. By integrating these perspectives, we gain insight into the complex ways in which adolescents negotiate ethnicity into their formation of self-concept. Such knowledge can help us better understand the role that ethnicity plays in the developmental processes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a NICHD grant 1R01HD055436-01A1 awarded to the author and to J. Nicole Shelton. The authors thank the many research assistants of the Youth Experience Study for their help with data collection. The authors also thank the school personnel and students for participating in this study.

References

- Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK. Cluster Analysis. Iowa City: Sage University Papers; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bracey JR, Bamaca MY, Umana-Taylor AJ. Examining ethnic identity and self-esteem among biracial and monoracial adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33(2):123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd CM, Chavous TM. Racial identity, school racial climate, and school intrinsic motivation among African American youth: The importance of person-context congruence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(4):849–860. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman CM, Eccles JS, Malanchuk O. Identity negotiation in everyday settings. In: Downey G, Eccles JS, Chatman CM, editors. Navigating the Future: Social Identity, Coping and Life Tasks. New York, NY: Russell Sage Press; 2005. pp. 116–139. [Google Scholar]

- Cheryan S, Monin Bt. ‘Where Are You Really From?’: Asian Americans and Identity Denial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89(5):717–730. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Jr, Strauss L. The everyday functions of African American identity. In: Swim JK, editor. Prejudice: The target’s perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc; 1998. pp. 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q, Devos T, Smalarz L. Perpetual foreigner in one’s own land: Potential implications for identity and psychological adjustment. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2011;30(2):133–162. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2011.30.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Wang Y, Deng S, Alvarez R, Li J. Accent, perpetual foreigner stereotype, and perceived discrimination as indirect links between English proficiency and depressive symptoms in Chinese American adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(1):289–301. doi: 10.1037/a0020712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;3:551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PP, Wout D, Nguyen H, Sellers RM, Gonzalez R. Investigating the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity in two samples: The development of the MIBI-S 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Meeus W, Iedemaa J, Helsen M, Vollebergh W. Patterns of adolescent identity development: Review of literature and longitudinal analyses. Developmental Review. 1999;19:419–461. [Google Scholar]

- Parham TA. Cycles of psychological Nigresence. The Counseling Psychologist. 1989;17:187–226. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Stages of ethnic identity in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1989;9:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: A review and integration. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1991;13(2):193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. In: Bernal ME, editor. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. SUNY series, United States Hispanic studies. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1993. pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19(3):301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, Sellers RM, Chavous TM, Smith MA. The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(3):715–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutland A, Cameron L, Bennett L, Ferrell J. Interracial contact and racial constancy: A multi-site study of racial intergroup bias in 3–5 year old Anglo-British children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26(6):699–713. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Scottham KM, Sellers RM. The Status model of racial identity development in African American adolescents: Evidence of structure, trajectories and well-being. Child Development. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, Smith MA. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:805–815. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN, Cooke DY, Chavous TM, Rowley SAJ, Smith MA, editors. A Multidimentional Model of Racial Identity: Assumptions, Findings, and Future Directions. Hampton, VA: Cobb & Henry; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM. Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2(1):18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, Azmitia M. A Narrative approach to ethnic idenitty in emerging adulthood: Bringing lifet to the identity status model. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(4):1012–1027. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ, Gonzales-Backen MA, Guimond AB. Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity: Is there a developmental progression and does growth in ethnic identity predict growth in self-esteem? Child Development. 2009;80(2):391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ, Vargas-Chanes D, Garcia CD, Gonzales-Backen M. A longitudinal examination of Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity, coping with discrimination, and self-esteem. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28(1):16–50. [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, Sellers RM. African American Racial Identity Across the Lifespan: Identity Status, Identity Content, and Depressive Symptoms. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1504–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]