Abstract

In the context of obesity epidemic, no large population study has extensively investigated the relationships between total and abdominal adiposity and large artery structure and function nor have such relationships been examined by gender, by age, by hypertensive status. We investigated these potential relationships in a large cohort of community dwelling volunteers participating the SardiNIA Study.

Methods and Results

Total and visceral adiposity and arterial properties were assessed in 6,148 subjects, aged 14–102 in a cluster of 4 towns in Sardinia, Italy. Arterial stiffness was measured as aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV), arterial thickness and lumen as common carotid artery (CCA) intima-media thickness (IMT) and diameter – respectively. We reported a nonlinear relationship between total and visceral adiposity and arterial stiffness, thickness, and diameter. The association between adiposity and arterial properties was steeper in women than in men, in younger than in older subjects. Waist correlated with arterial properties better than BMI. Within each BMI quartile, increasing waist circumference was associated with further significant changes in arterial structure and function.

Conclusion

The relationship between total or abdominal adiposity and arterial aging (PWV and CCA IMT) is not linear as described in the current study. Therefore, BMI- and/or waist-specific reference values for arterial measurements might need to be defined

Keywords: arteries, arterial stiffness, carotid intima-media thickness, obesity, waist circumference, population study

INTRODUCTION

Obesity has become an increasingly alarming epidemic. Approximately 65% of the US population (1) and more than one billion people worldwide (2) are overweight or obese. Increases have been observed in men and women, at all ages and at all educational levels (3).

Obesity represents a major independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (4–5). However, there is considerable heterogeneity in the risks associated with excess adiposity. Large studies have suggested that waist circumference, as an indicator of abdominal obesity rather than total adiposity, is a better predictor of the risk of CV disease than adiposity or body-mass index (BMI) (6–9). Abdominal adiposity is significantly associated with the development of cardiovascular diseases independent of total adiposity (4, 10). Thus, we also focused on the effect of increasing waist circumference within each quartile of BMI – from the normal weight to the obese range of BMI.

The CV burden associated with obesity may differ by gender, in younger and older subjects, in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. The prevalence of obesity is usually greater in women than in men (11) and increases with advancing age (12). Obesity is associated with greater mortality in younger than in older men, but no age-specific difference is observed in women (13). Despite a greater prevalence of hypertension among obese subjects, obese subjects with hypertension have been reported to have paradoxically fewer CV events than individuals of normal weight (14–16)

One mechanism by which obesity can promote arterial damage and its progression to the occurrence of cardiovascular events may be an effect due to remodeling of large arteries. Numerous studies suggest that obesity is associated with large artery stiffening and thickening (17–21), i.e. established risk factors for adverse CV outcomes (22–24).

To date, there are no large population studies that have extensively investigated the relationships between total and abdominal adiposity and large artery stiffness and thickness – estimated as aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV) and carotid intima-media thickness (IMT), respectively – nor have such relationships been examined by gender, by age, by hypertensive status. The purpose of the present study is to investigate these potential relationships in a large cohort of community dwelling volunteers participating the SardiNIA Study.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study population

The SardiNIA Study investigates the genetics and epidemiology of complex traits/phenotypes, including CV risk factors and arterial properties, in a Sardinian founder population (25–26). Over a 3-yr period, from November 2001 to December 2004, all residents aged 14 years and older in 4 towns of Sardinia Region, Italy were invited to participate in the Study. The response rate was 60%, resulting in enrolment of 6148 participants aged 14–102 years old. Study design and measurements have described previously (25–26).

All subjects gave written informed consent to participate the Study: The entire study was approved by our Institutional Reviewe Board and it has been conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Hypertension was defined as an average BP ≥ 140/90 mm Hg or if the participant was taking antihypertensive medications.

Adiposity and obesity definition

Height, weight and waist circumference (midway between the inferior margin of the last rib and the crest of the ileum, in a horizontal plane) were determined for all participants. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg)/height (m)2. BMI was adopted as indicator of total adiposity and waist circumference as indicator of abdominal adiposity.

As previously indicated (26), we defined normal weight (BMI < 25 Kg/m2), overweight (BMI = 25–29.9 Kg/m2), and obese individuals (BMI ≥ 30 Kg/m2). Abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference ≥ 88 cm for women and ≥ 102 cm for men.

Arterial stiffness, thickness, and lumen

Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV) was measured as previously described (26). A minimum of 10 arterial flow waves from the right common carotid artery and the right femoral artery were recorded simultaneously using nondirectional transcutaneous Doppler probes (Model 810A, 9 to 10-Mhz probes, Parks Medical Electonics, Inc, Aloha, OR), and averaged using the QR interval on ECG trace for synchronization. The foot of the flow, i.e., the point of systolic flow onset, was identified off-line by a custom-designed computer algorithm, and verified or manually adjusted by the reader after visual review. The time differential between the feet of simultaneously recorded carotid and femoral flow waves was then measured. The distance traveled by the flow wave was measured with an external tape measure over the body surface, as the distance from the right carotid sampling site to the manubrium subtracted from the distance from the manubrium to the right femoral sampling site. PWV was calculated as the distance traveled by the flow wave divided by the time differential.

High-resolution B-mode carotid ultrasonography was performed by use of a linear-array 5-to 7.5-MHz transducer (HDI 3500-ATL Ultramark Inc) as previously described (26). The subject lay in the supine position in a dark, quiet room. The stabilized BP after 15 minutes from the onset of testing was used for subsequent analyses. The right common carotid artery (CCA) was examined with the head tilted slightly upward in the midline position. The transducer was manipulated so that the near and far walls of the CCA were parallel to the transducer footprint and the lumen diameter was maximized in the longitudinal plane. A region 1.5 cm proximal to the carotid bifurcation was identified, and the IMT of the far wall was evaluated as the distance between the luminal-intimal interface and the medial-adventitial interface. CCA intima-media thickness (IMT) was measured on the frozen frame of a suitable longitudinal image with the image magnified to achieve a higher resolution of detail. The IMT measurement was obtained from 5 contiguous sites at 1-mm intervals, and the average of the 5 measurements was used for analyses. CCA diastolic diameter was individuated through an ECG gating and measured similarly to IMT.

PWV, CCA IMT and diameter measurements were performed off-line by a single observer (A. Scuteri) who was blinded to the identity of participants.

Medications

All the analyses of the current study were run in the whole population and, separately, in the 5310 subjects not on antihypertensive, antidiabetic, or lipid-lowering medications.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. All analyses are performed using the SAS package for Windows (9.1 Version Cary, NC). Differences in mean values for each of the measured variables among groups are compared by ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons. An ANCOVA analysis is employed to test for interactions among adiposity and age, gender, and hypertension.

Univariate and multivariable linear regression analyses for continuous variables are conducted to detect associations of covariates and arterial structure or function. These models are constructed with arterial stiffness or thickness, alternatively, as dependent variables. A two-sided p value < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

RESULTS

Study population characteristics are listed in Table 1, whereas the Table 2 illustrates the study population profile according to different age group. Increasing age was accompanied by a progressive increase in PWV, CCA IMT, and CCA diameter values.

Table 1.

Description of study population (The SardiNIA Study)

| Mean ± SD | Median | Interquartile Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.7 ± 17.6 | 42.2 | 27.7 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 25.4 ± 4.7 | 24.8 | 6.3 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 84.8 ± 13.1 | 84.0 | 20.0 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 90.1 ± 23.6 | 85.7 | 15.0 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 208.6 ± 42.2 | 206.9 | 57.8 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 127.0 ± 35.0 | 124.9 | 47.6 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 64.2 ± 14.9 | 62.7 | 19.2 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 85.2 ± 52.7 | 70.8 | 53.5 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 125.8 ± 18.4 | 122.5 | 24.0 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.6 ± 10.5 | 77.0 | 14.0 |

| PP (mmHg) | 48.7 ± 13.0 | 47.0 | 15.0 |

| MBP (mmHg) | 93.6 ± 12.1 | 92.0 | 16.3 |

| PWV (cm/sec) | 672 ± 227 | 615 | 238 |

| CCA IMT (mm) | 0.55 ± 0.11 | 0.52 | 0.12 |

| CCA diameter (mm) | 5.41 ± 0.68 | 5.3 | 0.9 |

| Women (%) | 57.5 | N/A | N/A |

| Overweight (%) | 17.1 | N/A | N/A |

| Obese (%) | 15.7 | N/A | N/A |

| Abdominal obesity (%) | 22.1 | N/A | N/A |

| Hypertension (%) | 29.1 | N/A | N/A |

| Antihypertensive medication (%) | 9.7 | N/A | N/A |

| Antidiabetic medications (%) | 2.1 | N/A | N/A |

| Insulin (%) | 0.7 | N/A | N/A |

| Statin (%) | 2.5 | N/A | N/A |

| Prevalent Myocardial Infarction (%) | 0.9 | ||

| Prevalent Stroke (%) | 0.8 |

Table 2.

Study population profile according to different age group

| Age group | P (ANOVA) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 35 yrs (n = 2161) | 35–49 yrs (n = 1760) | 50–64 yrs (n = 1325) | ≥ 65 yrs (n = 877) | ||

| Age (years) | 25.1 ± 6.1 | 42.1 ± 4.3 | 57.1 ± 4.3 | 72.5 ± 6.1 | 0.0001 |

| Women (%) | 58.0 | 58.7 | 56.1 | 55.8 | 0.32 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 22.5 ± 3.5 | 25.4 ± 4.2 | 27.9 ± 4.4 | 28.4 ± 4.4 | 0.0001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 76.8 ± 9.9 | 84.3 ± 11.6 | 91.8 ± 12.0 | 94.9 ± 11.9 | 0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 82.2 ± 16.6 | 87.9 ± 16.7 | 97.9 ± 28.9 | 102.2 ± 31.5 | 0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 186.4 ± 37.0 | 213.5 ± 38.2 | 229.3 ± 39.9 | 221.7 ± 40.6 | 0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 109.9 ± 29.8 | 131.5 ± 32.5 | 143.2 ± 34.2 | 135.7 ± 36.0 | 0.0001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 62.4 ± 14.7 | 64.1 ± 14.6 | 65.6 ± 14.9 | 66.5 ± 15.6 | 0.0001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 69.2 ± 42.5 | 86.8 ± 55.0 | 101.1 ± 57.2 | 97.6 ± 52.2 | 0.0001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 115.7 ± 11.7 | 122.4 ± 15.1 | 135.3 ± 18.3 | 142.9 ± 19.3 | 0.0001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 71.2 ± 7.4 | 78.2 ± 9.9 | 83.2 ± 10.2 | 82.5 ± 10.0 | 0.0001 |

| PP (mmHg) | 44.9 ± 9.7 | 44.4 ± 10.0 | 52.1 ± 12.9 | 60.6 ± 15.8 | 0.0001 |

| MBP (mmHg) | 86.1 ± 7.7 | 92.9 ± 10.9 | 97.9 ± 28.9 | 102.5 ± 11.5 | 0.0001 |

| PWV (cm/sec) | 521 ± 111 | 637 ± 135 | 781 ± 197 | 970 ± 273 | 0.0001 |

| CCA IMT (mm) | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 0.53 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.10 | 0.70 ± 0.14 | 0.0001 |

| CCA diameter (mm) | 5.1 ± 0.5 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 6.0 ± 0.8 | 0.0001 |

| Overweight (%) | 6.4 | 16.6 | 28.8 | 27.1 | 0.0001 |

| Obese (%) | 3.7 | 12.7 | 27.1 | 34. | 0.0001 |

| Abdominal Obesity(%) | 4.8 | 15.9 | 38.5 | 52.9 | 0.0001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 4.4 | 21.1 | 50.9 | 73.7 | 0.0001 |

| Antihypertensive medication (%) | 0.1 | 3.0 | 17.2 | 35.7 | 0.0001 |

| Antidiabetic medications (%) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 7.3 | 0.0001 |

| Insulin (%) | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.0001 |

| Statin (%) | - - | 0.9 | 4.1 | 9.7 | 0.0001 |

Univariate linear regression revealed that BMI is significantly positively correlated with arterial stiffness (r2 = 0.230, p < 0.0001), thickness (r2 = 0.139, p < 0.0001), and diameter (r2 = 0.230, p < 0.0001). Significant positive relationship between waist circumference and large artery properties was observed and appeared to be stronger (higher correlation coefficients) than those for BMI: specifically, for arterial stiffness (r2 = 0.245, p < 0.0001), thickness (r2 = 0.176, p < 0.0001), and diameter (r2 = 0.240, p < 0.0001).

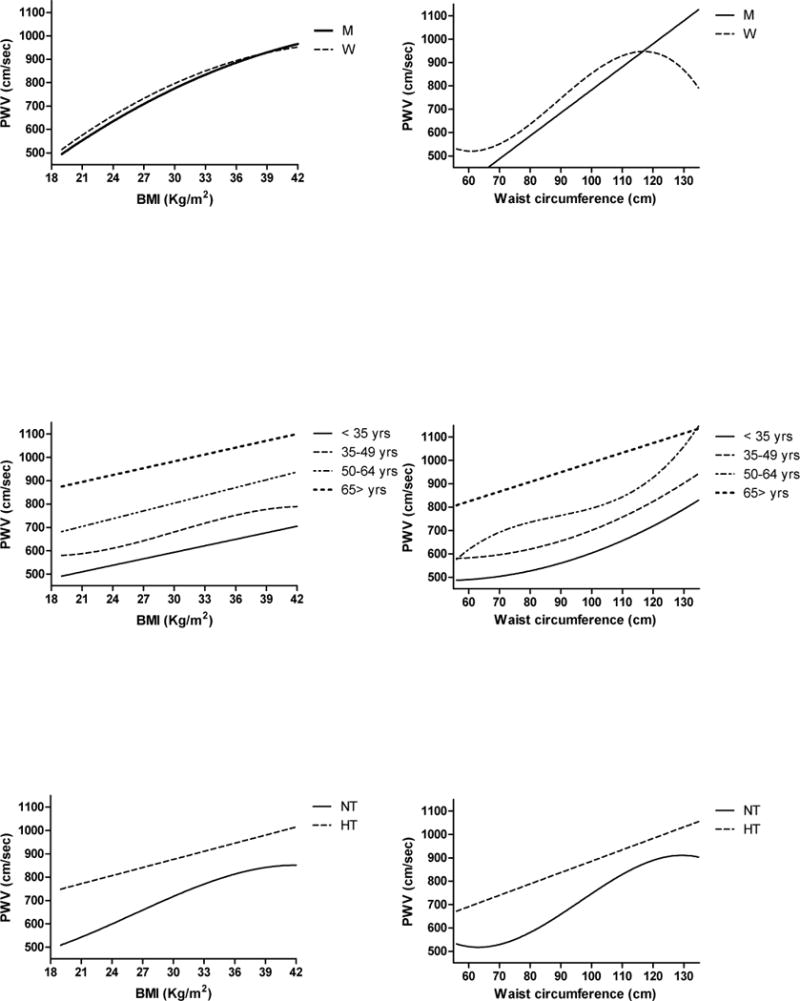

Total adiposity relationship with arterial stiffness

The relationship between BMI and arterial stiffness, measured as PWV, is best described by a quadratic relationship in the entire SardiNIA population and in both men and women (Figure 1 top left panel) – in which was stronger (r2 = 0.263, p < 0.0001) than in men (r2 = 0.175, p < 0.0001). This relationship remained significant even after controlling for age, sex, SBP, DBP, LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose levels.

Figure 1.

Best-fit lines describing the association between arterial stiffness (PWV) and total adiposity (BMI) (left column) or abdominal adiposity (waist circumference) (right column) according to gender (top panels), age group (middle panels), or hypertension (bottom panels). Best fit line and coefficient of determination (r2) of each line are listed in Table 3.

While age is strongly correlated with PWV, the effects of BMI on PWV do not differ significantly across age groups (interaction term p = 0.62), although the association appears weaker in subjects > 65 years. The best fit line indicated a linear relationship between BMI and PWV at all ages, except in subjects 35 to 49 years old in whom the best fit line is a cubic relationship (Table 2 and Figure 1 middle left panel). No gender difference in the relationship between total adiposity and arterial stiffness is observed across age groups (interaction term BMI*gender*age group p = 0.08).

BMI is a stronger correlate of PWV in normotensive than in hypertensive subjects (interaction term BMI* hypertensive status p < 0.0001). Of note the best fit line for the relationship between total adiposity and arterial stiffness is cubic in normotensive subjects (r2 = 0.209, p < 0.0001) and linear in hypertensive ones (r2 = 0.043, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1 bottom left panel and Table 3).

Table 3.

Total (left columns) and visceral (right columns) adiposity association with arterial properties

| BMI | Waist circumference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best fit | r2 | Best fit | r2 | |

| PWV | ||||

| All | Q | 0.224 | C | 0.243 |

| Men | Q | 0.175 | L | 0.228 |

| Women | Q | 0.263 | C | 0.289 |

| Age group | ||||

| < 35 yrs | L | 0.083 | Q | 0.070 |

| 35–49 yrs | C | 0.117 | Q | 0.102 |

| 50–64 yrs | L | 0.062 | C | 0.078 |

| 65 > yrs | L | 0.026 | L | 0.032 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Normotensive | C | 0.209 | C | 0.209 |

| Hypertensive | L | 0.043 | L | 0.051 |

| CCA IMT | ||||

| All | C | 0.141 | C | 0.174 |

| Men | C | 0.119 | C | 0.175 |

| Women | Q | 0.155 | L | 0.166 |

| Age group | ||||

| < 35 yrs | Q | 0.012 | C | 0.020 |

| 35–49 yrs | C | 0.037 | L | 0.037 |

| 50–64 yrs | L | 0.011 | L | 0.031 |

| 65 > yrs | L | 0.003 | L | 0.013 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Normotensive | C | 0.125 | C | 0.141 |

| Hypertensive | L | 0.015 | L | 0.035 |

| CCA Diameter | ||||

| All | Q | 0.182 | Q | 0.239 |

| Men | Q | 0.151 | Q | 0.183 |

| Women | Q | 0.159 | L | 0.166 |

| Age group | ||||

| < 35 yrs | Q | 0.146 | Q | 0.180 |

| 35–49 yrs | Q | 0.116 | Q | 0.179 |

| 50–64 yrs | Q | 0.063 | L | 0.122 |

| 65 > yrs | L | 0.011 | L | 0.030 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Normotensive | Q | 0.163 | Q | 0.210 |

| Hypertensive | Q | 0.035 | Q | 0.077 |

L = linear ; Q = quadratic ; C = cubic

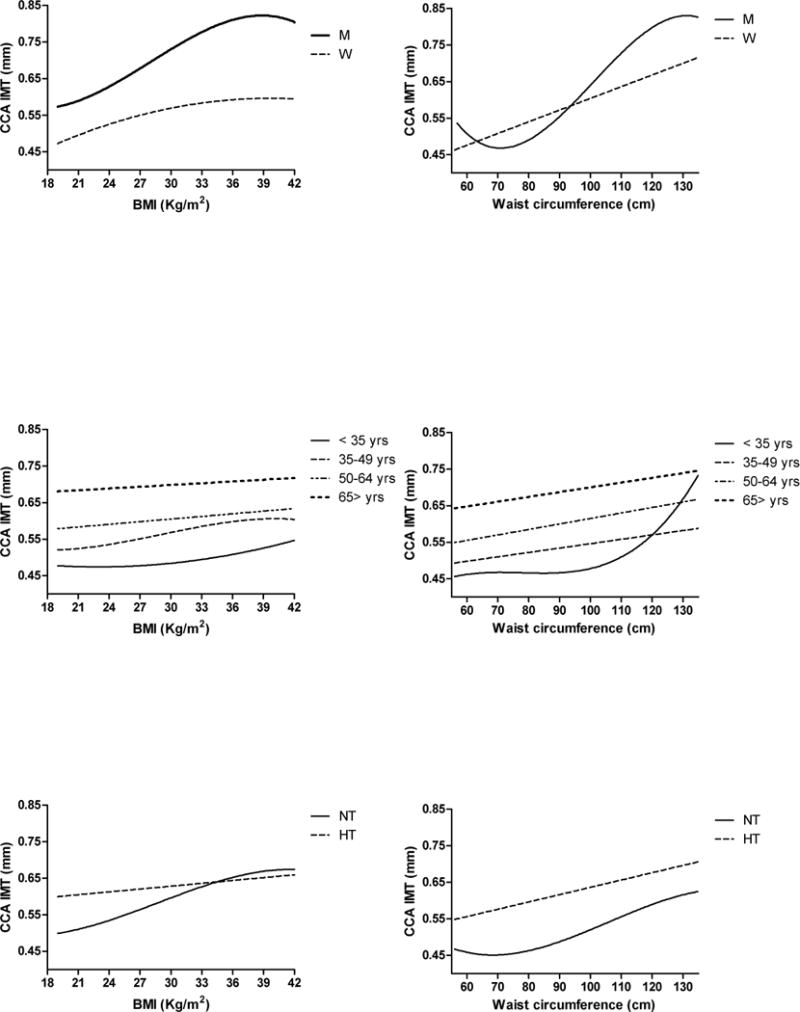

Total adiposity relationship with arterial thickness

The relationship between BMI and arterial thickness, measured as CCA IMT, is best described by a cubic relationship in the entire SardiNIA population and in men, whereas a quadratic shape best describes th is relationship in women (Figure 2 top left panel) – in which it was stronger (r2 = 0.155, p < 0.0001) than in men (r2 = 0.119, p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Best-fit lines describing the association between arterial thickness (CCA IMT) and total adiposity (BMI) (left column) or abdominal adiposity (waist circumference) (right column) according to gender (top panels), age group (middle panels), or hypertension (bottom panels). Best fit line and coefficient of determination (r2) of each line are listed in Table 3.

This relationship remained signifcant even after controlling for age, sex, SBP, DBP, LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose levels.

Age is significantly correlated with CCA IMT and the association of BMI and CCA IMT significantly differs across age groups (interaction term p < 0.01) and is weaker and statistically not significant in subjects 65 years and older. The best fit line for the relationship between BMI and CCA IMT is quadratic in subjects < 35 years (r20.012, p < 0.001), cubic in those 35 to 49 years (r2 = 0.037, p < 0.0001), and linear in those 50 to 64 years old (r2 = 0.011, p < 0.001) (Figure 2 middle left panel).

BMI is a stronger correlate of CCA IMT in normotensive than in both men and women hypertensive subjects (interaction term BMI* hypertensive status p < 0.0001). The best fit line for the relationship between total adiposity and arterial thickness is cubic in normotensive subjects (r2 = 0.125, p < 0.0001) and quadratic in hypertensive ones (r2 = 0.015, p < 0.0001) (Figure 2 bottom left panel).

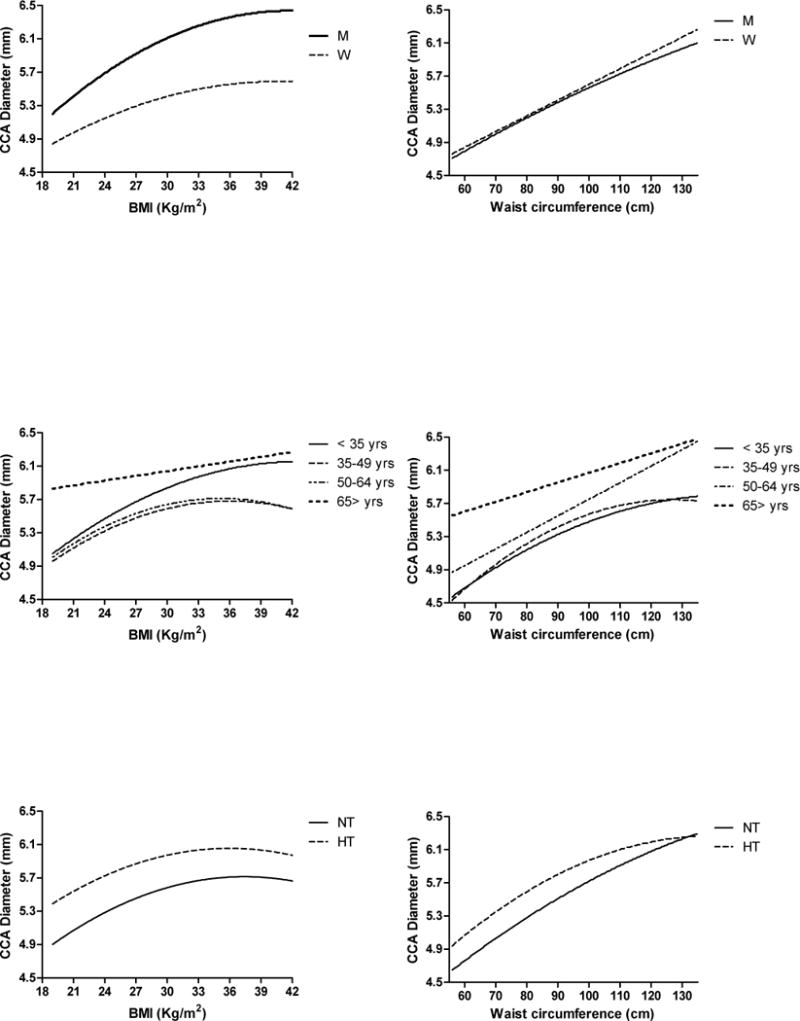

Total adiposity relationship with arterial lumen

The relationship between BMI and arterial lumen, measured as CCA diameter, is best described by a quadratic relationship for the entire SardiNIA population and in each gender (Figure 3 top left panel), that was significantly stronger in women (r2 = 0.159, p < 0.0001) than in men (r2 = 0.151, p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Best-fit lines describing the association between arterial lumen (CCA Diameter) and total adiposity (BMI) (left column) or abdominal adiposity (waist circumference) (right column) according to gender (top panels), age group (middle panels), or hypertension (bottom panels). Best fit line and coefficient of determination (r2) of each line are listed in Table 3.

This relationship remained signifcant even after controlling for age, sex, SBP, DBP, LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose levels.

Age is significantly correlated with CCA diameter. The effects of BMI on CCA diameter significantly differs across age groups (interaction term p < 0.0001) and becomes progressively weaker with advancing age. The best fit line for the relationship between BMI and CCA diameter is quadratic in subjects < 35 years (r2 = 0.146, p < 0.0001), in those 35 to 49 years (r2 = 0.116, p < 0.0001), and in those 50 to 64 years old (r2 = 0.063, p < 0.0001), but linear in subjects 65 years and older (r2 = 0.011, p < 0.001) (Figure 3 middle left panel).

BMI is a stronger correlate of CCA diameter in normotensive than in hypertensive subjects (interaction term BMI* hypertensive status p < 0.0001), with no gender difference. The best fit line for the relationship between total adiposity and arterial lumen diameter is quadratic in both normotensive (r2 = 0.163, p < 0.0001) and hypertensive subjects (r2 = 0.035, p < 0.0001) (Figure 3 bottom left panel).

Abdominal adiposity relationship with arterial properties

The analysis of the correlation between waist circumference and arterial properties resulted in a slightly higher r2 than those observed for the correlation with BMI in each and every group of subjects (see Table 3 right columns). The best fit line describing the association between waist circumference and arterial stiffnes, or thickness, or lumen has virtually the same shape (linear or higher-order correlation) as described for BMI.

These relationships remained significant independently of age, sex, SBP, DBP, LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose levels.

Secondary analyses conducted in the 5310 subjects not on anti-hypertensive, antidiabetic, or lipid-lowering medications, showed that the relationship of total or abdominal adiposity with arterial properties was similar to that described in the general population.

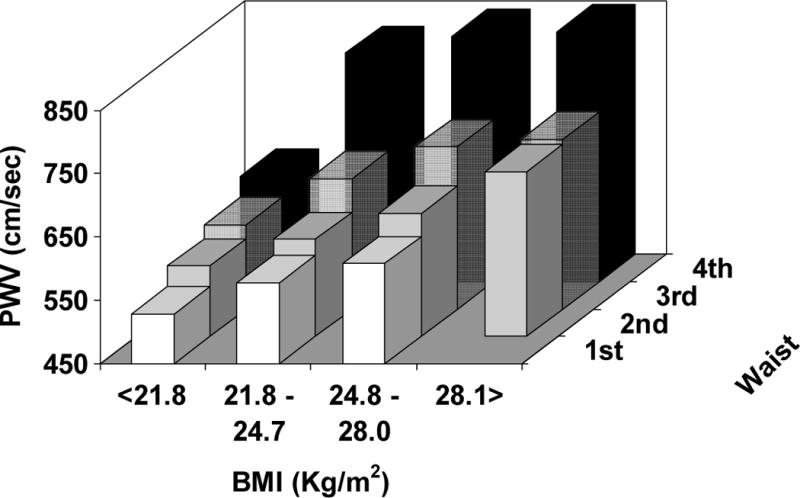

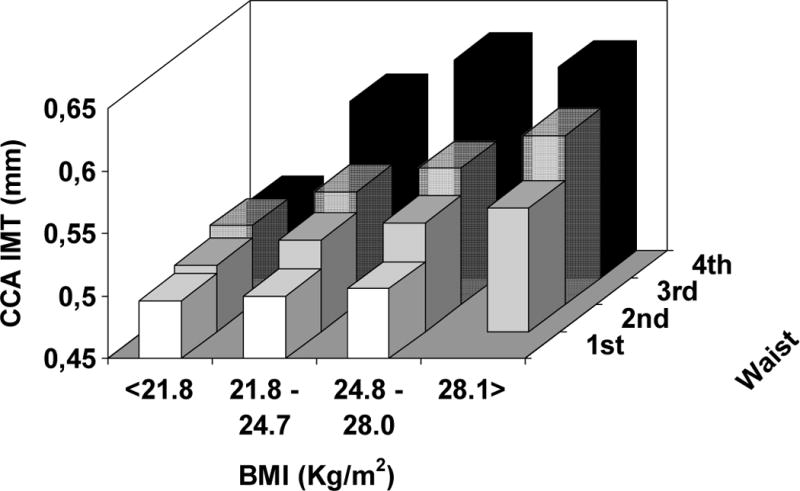

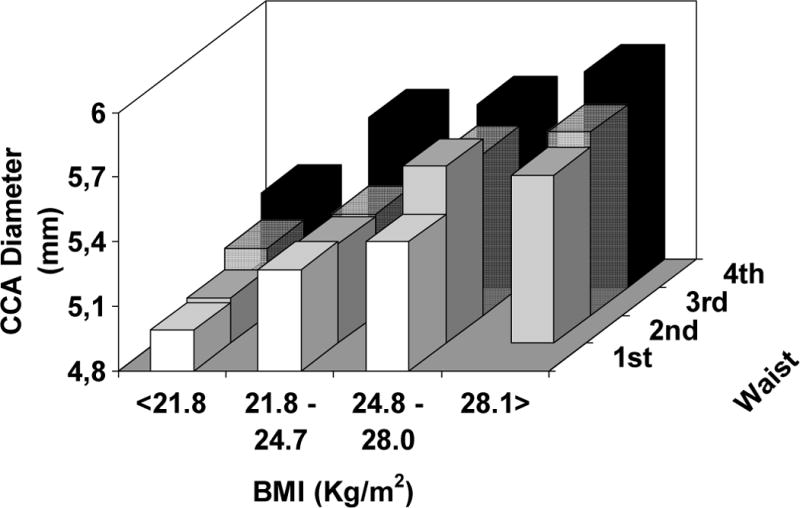

When we focused on the effect of increasing waist circumference within each quartile of BMI – from the normal weight to the obese range of BMI, increasing abdominal adiposity significantly magnifies the arterial remodeling in each BMI group, both in lean and in the obese subjects by standard clinical definition (see Figure 4) (p < 0.001 for PWV and CCA IMT, p < 0.05 for CCA diameter – after controlling for age, sex, SBP, DBP, LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose levels).

Figure 4.

Average levels of arterial stiffness (top panel), thickness (middle panel), and lumen diameter (bottom panel) according to quartiles of BMI (21.8 – 24.8 – 28.1 Kg/m2) and gender-specific quartiles of waist circumference (men: 82 – 90 – 98 cm ; women: 71 – 79 – 89 cm).

DISCUSSION

The present study in a large cohort of community dwelling men and women of broad age range demonstrates nonlinear relationships between total and visceral adiposity and arterial stiffness, thickness, and diameter. Indeed, a non-linear relationship between total adiposity and mortality has recently been reported (13). Specifically, a higher risk for deaths was observed in the lower (< 23 Kg/m2) and in the higher (≥ 26.6 Kg/m2) BMI groups than in the middle BMI groups (13). Obesity and central obesity are more prevalent in women with coronary disease than in men (11). Obesity is also more prevalent in older subjects (12), in whom a higher BMI, in the “near-obese” range, has been associated with optimal survival (27–29).

The significant association between adiposity and arterial stiffness and thickness in the SardiNIA population has been reported in other study populations and has been found to be independent of blood pressure levels, age, ethnicity (19–21, 30–31). This association was stronger with visceral than with total adiposity (19–20, 32), as we confirmed in the present study.

Recently, a large prospective collaborative study clearly showed that the burden of BMI and waist circumference on the risk of CV disease was three-to-four times stronger in the age group 40–59 than in subjects older than 70 years, but it did not differ between men and women (33). However, the observation of the present study of a steeper association between total or abdominal adiposity and arterial properties in women than in men as well as in younger than in older subjects is novel.

The relationship between adiposity and arterial properties has been described even in children and teenagers (34–35), indicating that a long exposure to increased fatness is not necessarily a prerequisite for arterial stiffening and thickening. Rather, the association between adiposity and arterial problems in children may reflect lifestyle or genetic factors operating in very early phase of life (36–37), or may indicate that the complexity of age-associated changes in arterial remodeling (38) are not “active” and the response of arteries to individual traditional CV risk factors (adiposity in our case) is functional, i.e. occurring without “organized” structural wall changes (39). However, it is noteworthy that even at older ages, excess adiposity is associated with stiffer and thicker large arteries.

Surprisingly, the relationship of total or abdominal adiposity and arterial remodeling is stronger in normotensive than in hypertensive subjects of our population. Although the relationship between adiposity and higher blood pressure is linear, and is evident even in the nonobese range (40) and although hypertension is a major determinant of arterial thickening and stiffening (39, 41), obese hypertensives have been reported to have a “paradoxically” lower risk of CV events than lean hypertensives (14–15). Whether this paradox may, at least partly, be related to the relatively weaker impact of obesity on arterial structure and function in hypertensive than in normotensive subjects remains to be determined. Certainly, higher PWV or CCA IMT values in hypertensive subjects might influence the weaker observed relationship with adiposity markers in hypertension.

Within each BMI quartile, increasing waist circumference was associated with further significant changes in arterial structure and function. Indeed, waist circumference has been reported as a significant predictor of new onset metabolic syndrome (42–43), that, in turn, significantly increases arterial stiffness and thickness at any age and in both men and women (39, 44). However, two prior studies reported that the significant association between visceral adiposity and PWV (45) or CCA IMT (46) was dependent upon BMI, so that further adjustment for BMI led to non-significant findings.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional analysis presented does not allow pathophysiological speculations. Secondly, the relatively larger representation of younger subjects in this cohort of South-European (lower CV risk) population does not allow generalization of our findings to other populations. Rather, cross-cultural comparison of the reported relationship are welcome even though the study population consisted of more than 6000 subjects. A potential additional limitation is sub-stratification of subjects into small groups when combining adiposity and gender or age groups or hypertension. Waist-to-hip ratio has been reported to show a graded and highly significant association with myocardial infarction risk in different ethnic populations (47). It was not available in our population, so it was not possible to test the correlation between arterial stiffness and thickness with this additional measure of adiposity.

Clinical implications

The observed non.linear association between adiposity and arterial properties in specific groups of subjects has relevant clinical implications. In fact, it implies that smaller reduction in adiposity (for instance, by lifestyle interventions) will results in a dramatically greater impact on arterial stiffness or thickness – and, thus, on individual CV risk profile – in specific groups (women, middle-age subjects).

Accordingly, resources should be allocated to try reference and normative values for arterial stiffness and thickness accounting also for obesity or specific for different adiposity groups (overweight, obese). Indeed, a recent study firstly provided reference values for arterial stiffness (48). However, in this remarkable study no stratification for adiposity was specifically analysed.

Additionally, it might be relevant to identify subjects with greater adiposity and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines circulating levels. In fact, higher leptin and hsCRP have been found to be associated with stiffer and low adiponectin and high interleukin 6 levels with thicker large arteries, respectively, independently from traditional CV risk factors and metabolic syndrome (49). Thus, those subjects might have an accelerated arterial aging and a greater risk for CV events.

Waist circumference can be a useful measurement to discriminate and follow-up subjects who are at risk for accelerated arterial aging (and, thus, likely of CV events) above and beyond the measurement of BMI. The present findings recall the relevance of routine clinical measurement of waist circumference. Although measurement of waist circumference is easy and not time-consuming, yet it has not widely adopted in clinical practice (50).

Our results contribute to further emphasize the recent findings of 58 studies investigating the association between total or abdominal adiposity and CV disease (33). Indeed, the Authors remarked that adiposity may represent an intermediate CV risk factor whose clinical assessment is critical at least because it provides a useful clinical tool to promote lifestyle and behavioural changes and to improve CV risk communication (33).

Another relevant clinical implication of the present findings is a need to establish “normal” or reference values for adiposity to facilitate a more accurate individual CV risk stratification. In fact, the current waist circumference cut points were derived by regression from an “obese” BMI (51). However, approximately 14% of women and 1% of men with normal BMI (18.5–24.9kg/m2) have a “fat” waist circumference (52). Thus, waist circumference may identify patients who are “metabolically obese” and at risk of accelerated arterial aging, independent of their level of total adiposity (BMI)

Indeed, it has been showed that BMI-specific waist threshold values provided a better indicator of CV risk than the currently recommended waist circumference cut offs (53). Studies are needed to establish waist cut offs that can assess CV risk that is not adequately captured by BMI and routine clinical assessments. These reference values likely need to be specific by gender, age groups, ethnicity, hypertension. Such an identification could imply allocation to lifestyle and pharmacological therapy of subjects who would not have been considered for treatment because of a normal BMI.

Acknowledgments

We thank Monsignore Piseddu, Bishop of Ogliastra, the Mayors of Lanusei, Ilbono, Arzana, and Elini, the head of the local Public Health Unit ASL4, and the residents of the towns, for their volunteerism and cooperation. In addition we are also grateful to the Mayor and the administration in Lanusei for providing and furnishing the clinic site.

The SardiNIA team was supported by Contract NO1-AG-1-2109 from the NIA

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging (USA)

Glossary

- AS

conceived and designed the research; acquired the data; analyzed and interpreted the data; performed statistical analysis; drafted the manuscript

- KT

made critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

- MO

acquired the data; made critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

- CHM

made critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

- DS

handled funding and supervision; made critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

- MU

handled funding and supervision; made critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

- EGL

conceived and designed the research; made critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galuska DA, Serdula M, Pamuk E, Siegel OZ, Byers T. Trends in overweight among US adults from 1987 to 1993: a multistate telephone survey. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1729–17. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.12.1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113:898–918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Despres JP. Cardiovascular disease under the influence of excess visceral fat. Crit Path Cardiol. 2007;6:51–59. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e318057d4c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366:1197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Expert Panel on the Identification Evaluation and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1855–67. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Comparison of abdominal adiposity and overall obesity in predicting risk of type 2 diabetes among men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:555–63. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Bautista L, Franzosi MG, Commerford P, Lang CC, Rumboldt Z, Onen CL, Lisheng L, Tanomsup S, Wangai P, Jr, Razak F, Sharma AM, Anand SS. INTERHEART Study. Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet. 2005;366:1640–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Despres JP, Lemieux I, Prud’homme D. Treatment of obesity: need to focus on high risk abdominally obese patients. Brit Med J. 2001;322:716–720. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pyorala K, Lehto S, De Bacquer D, De Sutter J, Sans S, Keil U, Wood D, De Backer G, EUROASPIRE I Group. EUROASPIRE II Group Risk factor management in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. Findings from the EUROASPIRE I AND II surveys. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1257–1265. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1438-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Bergmann M, Schulze MB, Overvad K, van der Schouw YT, Spencer E, Moons KG, Tjønneland A, Halkjaer J, Jensen MK, Stegger J, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Chajes V, Linseisen J, Kaaks R, Trichopoulou A, Trichopoulos D, Bamia C, Sieri S, Palli D, Tumino R, Vineis P, Panico S, Peeters PH, May AM, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, van Duijnhoven FJ, Hallmans G, Weinehall L, Manjer J, Hedblad B, Lund E, Agudo A, Arriola L, Barricarte A, Navarro C, Martinez C, Quirós JR, Key T, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Boffetta P, Jenab M, Ferrari P, Riboli E. General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2105–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uretsky S, Messerli FH, Bangalore S, Champion A, Cooper-Dehoff RM, Zhou Q, Pepine CJ. Obesity paradox in patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 2007;120:863–870. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wassertheil-Smoller S, Fann C, Allman RM, Black HR, Camel GH, Davis B, Masaki K, Pressel S, Prineas RJ, Stamler J, Vogt TM. Relation of low body mass to death and stroke in the systolic hypertension in the elderly program. The SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:494–500. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stamler R, Ford CE, Stamler J. Why do lean hypertensive patients have higher mortality rates than other hypertensive patients?: Findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. Hypertension. 1991;17:553–564. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuomilehto J. Body mass index and prognosis in elderly hypertensive patients: a report from the European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly. Am J Med. 1991;90:34S–41S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90434-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danias PG, Tritos NA, Stuber M, Botnar RM, Kissinger KV, Manning WJ. Comparison of aortic elasticity determined by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in obese versus lean adults. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:195–199. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnick L, Militianu D, Cunnings A, Pipe J, Evelhoch J, Soulen R. Direct magnetic resonance determination of aortic distensibility in essential hypertension: relation to age, abdominal visceral fat, and in situ intracellular free magnesium. Hypertension. 1997;30:654–659. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.3.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wildman RP, Mackey RH, Bostom A, Thompson T, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Measures of obesity are associated with vascular stiffness in young and older adults. Hypertension. 2003;42:468–473. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000090360.78539.CD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke GL, Bertoni AG, Shea S, Tracy R, Watson KE, Blumenthal RS, Chung H, Carnethon MR. The impact of obesity on cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical vascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:928–935. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taniwaki H, Kawagishi T, Emoto M, Shoji T, Kanda H, Maekawa K, Nishizawa Y, Morii H. Correlation between the intima-media thickness of the carotid artery and aortic pulse-wave velocity in patients with type 2 diabetes: vessel wall properties in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1851–1857. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.11.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boutouyrie P, Tropeano AI, Asmar R, Gautier I, Benetos A, Lacolley P, Laurent S. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of primary coronary events in hypertensive patients: a longitudinal study. Hypertension. 2002;39:10–15. doi: 10.1161/hy0102.099031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laurent S, Katsahian S, Fassot C, Tropeano AI, Gautier I, Laloux B, Boutouyrie P. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of fatal stroke in essential hypertension. Stroke. 2003;34:1203–1206. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000065428.03209.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, Burke GL, Wolfson SK., Jr Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pilia G, Chen WM, Scuteri A, Orru M, Albai G, Dei M, Lai S, Usala G, Lai M, Loi P, Mameli C, Vacca L, Deiana M, Olla N, Masala M, Cao A, Najjar SS, Terracciano A, Nedorezov T, Sharov A, Zonderman AB, Abecasis GR, Costa P, Lakatta E, Schlessinger D. Heritability of cardiovascular and personality traits in 6,148 Sardinians. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Orru℉ M, Albai G, Strait J, Tarasov KV, Piras MG, Cao A, Schlessinger D, Uda M, Lakatta EG. Age- and gender-specific awareness, treatment, and control of cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical vascular lesions in a founder population: The SardiNIA Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19:532–4. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens J, Cai J, Pamuk ER, Williamson DF, Thun MJ, Wood JL. The effect of age on the association between body mass index and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801013380101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bender R, Jockel KH, Trautner C, Spraul M, Berger M. Effect of age on excess mortality in obesity. JAMA. 1999;281:1498–1504. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.16.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabowski DC, Ellis JE. High body mass index does not predict mortality in older people: analysis of the Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:968–979. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toto-Moukouo JJ, Achimastos A, Asmar RG, Hugues CJ, Safar ME. Pulse wave velocity in patients with obesity and hypertension. Am Heart J. 1986;112:136–140. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90691-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li SX, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Bond MG, Tang R, Urbina EM, Berenson GS. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and carotid vascular changes in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. JAMA. 2003;290:2271–2276. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hegazi RA, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Evans RW, Kuller LH, Belle S, Yamamoto M, Edmundowicz D, Kelley DE. Relationship of adiposity to subclinical atherosclerosis in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Obes Res. 2003;11:1597–1605. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Separate and combined associations of body-mass index and abdominal adiposity with cardiovascular disease: collaborative analysis of 58 prospective studies. Lancet. 2011;377:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60105-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tounian P, Aggoun Y, Dubern B, Varille V, Guy-Grand B, Sidi D, Girardet JP, Bonnet D. Presence of increased stiffness of the common carotid artery and endothelial dysfunction in severely obese children: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358:1400–1404. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06525-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iannuzzi A, Licenziati MR, Acampora C, Salvatore V, Auriemma L, Romano ML, Panico S, Rubba P, Trevisan M. Increased carotid intima-media thickness and stiffness in obese children. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2506–2508. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scuteri A, Sanna S, Chen WM, Uda M, Albai G, Strait J, Najjar S, Nagaraja R, Orrú M, Usala G, Dei M, Lai S, Maschio A, Busonero F, Mulas A, Ehret GB, Fink AA, Weder AB, Cooper RS, Galan P, Chakravarti A, Schlessinger D, Cao A, Lakatta E, Abecasis GR. Genome-Wide Association Scan Shows Genetic Variants in the FTO Gene Are Associated with Obesity-Related Traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(7):e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scuteri A, Tesauro M, Rizza S, Iantorno M, Federici M, Lauro D, Campia U, Turriziani M, Fusco A, Cocciolillo G, Lauro R. Endothelial function and arterial stiffness in normotensive normoglycemic first-degree relatives of diabetic patients are independent of the metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;18:349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Lakatta EG. Arterial aging: is it an immutable cardiovascular risk factor? Hypertension. 2005;46:454–62. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000177474.06749.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scuteri A, Chen CH, Yin FC, Chih-Tai T, Spurgeon HA, Lakatta EG. Functional correlates of central arterial geometric phenotypes. Hypertension. 2001;38:1471–5. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.099291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones DW, Kim JS, Andrew ME, Kim SJ, Hong YP. Body mass index and blood pressure in Korean men and women: the Korean National Blood Pressure Survey. J Hypertens. 1994;12:1433–7. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199412000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Orru’ M, Usala G, Piras MG, Ferrucci L, Cao A, Schlessinger D, Uda M, Lakatta EG. The central arterial burden of the metabolic syndrome is similar in men and women: the SardiNIA Study. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:602–13. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scuteri A, Morrell CH, Najjar SS, Muller D, Andres R, Ferrucci L, Lakatta EG. Longitudinal paths to the metabolic syndrome: can the incidence of the metabolic syndrome be predicted? The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:590–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Czernichow S, Bertrais S, Oppert JM, Galan P, Blacher J, Ducimetière P, Hercberg S, Zureik M. Body composition and fat repartition in relation to structure and function of large arteries in middle-aged adults (the SU.VI.MAX study) Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:826–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takami R, Takeda N, Hayashi M, Sasaki A, Kawachi S, Yoshino K, Takami K, Nakashima K, Akai A, Yamakita N, Yasuda K. Body fatness and fat distribution as predictors of metabolic abnormalities and early carotid atherosclerosis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1248–52. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.7.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palaniappan L, Carnethon MR, Wang Y, Hanley AJG, Fortmann SP, Haffner SM, Wagenknecht L. Predictors of the incident metabolic syndrome in adults. The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:788–793. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Muller DC, Andres R, Hougaku H, Metter EJ, Lakatta EG. Metabolic syndrome amplifies the age-associated increases in vascular thickness and stiffness. JACC. 2004;43:1388–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Bautista L, Franzosi MG, Commerford P, Lang CC, Rumboldt Z, Onen CL, Lisheng L, Tanomsup S, Wangai P, Jr, Razak F, Sharma AM, Anand SS, INTERHEART Study Investigators Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet. 2005;366:1640–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness’ Collaboration. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: ‘establishing normal and reference values’. European Heart Journal. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, Kelley DE, Leibel RL, Nonas C, Kahn R, Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention. NAASO. Obesity Society. American Society for Nutrition. American Diabetes Association Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: a consensus statement from shaping America’s health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1647–52. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scuteri A, Orru M, Morrell C, Piras MG, Taub D, Schlessinger D, Uda M, Lakatta EG. Independent and additive effects of cytokine patterns and the metabolic syndrome on arterial aging in the SardiNIA Study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215:459–64. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. 1998;6:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ardern CI, Janssen I, Ross R, Katzmarzyk PT. Development of health-related waist circumference thresholds within BMI categories. Obes Res. 2004;12:1094–1103. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]