Abstract

The European Commission (EC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) jointly sponsored a workshop on October 18–20, 2011 in Brussels to discuss the feasibility and benefits of an international collaboration in the field of traumatic brain injury (TBI) research. The workshop brought together scientists, clinicians, patients, and industry representatives from around the globe as well as funding agencies from the EU, Spain, the United States, and Canada. Sessions tackled both the possible goals and governance of a future initiative and the scientific questions that would most benefit from an integrated international effort: how to optimize data collection and sharing; injury classification; outcome measures; clinical study design; and statistical analysis. There was a clear consensus that increased dialogue and coordination of research at an international level would be beneficial for advancing TBI research, treatment, and care. To this end, the EC, the NIH, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research expressed interest in developing a framework for an international initiative for TBI Research (InTBIR). The workshop participants recommended that InTBIR initially focus on collecting, standardizing, and sharing clinical TBI data for comparative effectiveness research, which will ultimately result in better management and treatments for TBI.

Key words: geriatric brain injury, head trauma, human studies, pediatric brain injury

Introduction

The European Commission (EC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a workshop on October 18–20, 2011 in Brussels to explore the feasibility of an international initiative for traumatic brain injury (TBI) research. The stimulus for the workshop stemmed from two previous symposia: “Promoting Effective Traumatic Brain Injury Research: EU and USA Perspectives,” National Neurotrauma Society, June 20101 and “Transatlantic Synergies to Promote Effective Traumatic Brain Injury Research,” American Association for the Advancement of Science, February 2011 (http://aaas.confex.com/aaas/2011/webprogram/Session2973.html). These meetings explored the scientific rationale and benefits of an international collaborative effort in the field of clinical TBI research and concluded that an international collaboration would be timely and of significant added value.

The Brussels workshop built on the work of the two previous symposia and brought together some 60 policy makers, scientists, clinicians, and patient and industry representatives from the European Union (EU), United States, Canada, China, and Australia to discuss the feasibility of an international collaboration in the field of TBI and define its scientific priorities. This article summarizes the contributions in each session and the rationale for establishing a program-level cooperation in the area of TBI.

TBI: Bottlenecks and Priorities for Action

Clinical bottlenecks: David Menon

There is good evidence of a global pandemic in TBI, culminating in significant costs to all societies, in terms of mortality, residual disability, health economic costs, and reduced productivity.2 Current figures may substantially underestimate the true incidence of TBI, because a community-based survey from Indiana suggests that 45% of mild TBIs (mTBIs)) are missed by standard criteria.3 Although most patients recover at least partially, others may continue to worsen over the years after TBI.4,5 Improvements in clinical care, coupled with the development of authoritative guidelines, have reduced mortality from severe TBI (sTBI) from 40 years ago,6 but improvement has slowed,7 and whereas there seems to be a benefit from treatment in specialist centers, improvements in favorable outcome are less obvious.8 Moreover, wide discrepancies in outcomes exist between centers and among countries. Reduction of mortality from trauma across the EU to levels in the Netherlands could potentially save 100,000 lives per year.9 The organization of health care systems can also have a major effect on the outcome of patients with a TBI. Several of these factors may have contributed to the failure of a number of novel neuroprotective interventions to translate into benefit in patients with a head injury.10,11 Multiple treatments are currently available, but there are still limitations to characterization and prognostication in individual patients. More rational approaches are needed for assigning or tailoring treatments to specific patients.

Modern imaging techniques, especially magnetic resonance (MRI), offer substantial advantages in understanding the progress of pathophysiology in TBI.12 A clear definition of the variance and sample size in MRI studies would potentially allow its use as a tool for elucidating mechanisms of injury. Also, the development of quantitative techniques to image target mechanisms (e.g., neuroinflammation and amyloid deposition) could provide valuable mechanistic endpoints in drug development. Neuropathology will be critical for validating imaging and other emerging biomarkers.

Management of TBI: The need for a global approach: Ji-yao Jiang

The opportunities for clinical TBI research are substantial in China, which reports approximately 1 million patients hospitalized with moderate to sTBI per year. The figures for mTBI are unknown, but are likely to be many multiples of this number. Centers in China have a substantial record of subject recruitment to both national and international TBI studies, including trials of hypothermia and decompressive craniectomy. A recently initiated observational study reported recruitment of over 7000 in-patients with sTBI in less than a year, with a plan to recruit 20,000 patients. Patterns of Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) at admission, outcomes, and other epidemiological data are concordant with similar case series from Western centers, suggesting similar clinical populations. The major cause of TBI in this cohort was motor vehicle incidents. Although regulatory processes can be slow, they are facilitated by local collaboration; rehabilitation and long-term follow-up may also be less accessible. At least some pharmaceutical firms have overcome those factors and involve Chinese centers in trials; overall, China provides substantial opportunities for clinical research.

Why is industry withdrawing from the TBI field?: Marie-Noelle Castel

Most pharmaceutical companies withdrew from the TBI field subsequent to the failure of clinical trials over the last 10–20 years. However, the discovery of new potential neuroprotective molecules has renewed interest in the field. Behavioral outcomes, biomarkers, imaging studies [including positron emission tomography (PET) ligands], and late endpoints (>6 months) in humans and animal models are needed to guide translational programs.

Companies such as Sanofi-Aventis have been encouraged by the increased recognition of TBI as a significant public health issue, both in armed conflict and in amateur and professional contact sports, which has resulted in substantial government funding by the Department of Defense (DoD) and National Institutes of health (NIH) in the United States, and now by the EU. They have also been encouraged by the recent development of more-integrated research strategies, which include tools for clinical research [e.g., Common Data Elements (CDEs); www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov], and the formation of effective national and multi-national research consortia. Participation in an international TBI research collaboration is attractive because it mitigates risk. Harmonization of the data-collection process and the resulting effects on clinical trial design are also significant advantages. The data obtained from new patient populations, particularly with mTBI, may facilitate subsequent clinical trials with this study population. Thus, involvement in a large multi-disciplinary consortium may help accelerate global development. However, pharmaceutical industry participation in an international collaboration requires an adequate framework for sharing intellectual property and risk, because the data will be shared and compounds may originate from academic research labs. Pharmaceutical companies do not object, but underscore that both risks and benefits of successful drug development need to be shared.

Although supportive of the plans to develop better disease classification and outcome measures, industry partners would need to ensure that such measures had regulatory approval before use in their trials. Indeed, early involvement of regulatory agencies in this endeavor is a distinct advantage, especially because the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has no fast-track route for TBI and other orphan conditions. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does have a fast-track process, but there is a significant latency before drugs can lock into this scheme, and more-effective implementation would be beneficial. However, it was also noted that data obtained from patients participating in trials in one country were usually admissible for regulatory approval in other countries, provided that an appropriate number or proportion of patients in the trial came from the country where regulatory approval was being sought. Last, there is a different regulatory system for biomarkers that also needs to be considered.

The needs of patients: Mary Baker

The public health effect of TBI raised in earlier talks was reinforced. In addition, the economic effect of disorders of the brain in the EU was described. It was estimated to be €798 billion in 2010,13 a proportion of which is because of TBI (€33 billion). At least in the UK, individuals viewed as in-patients in a neuroscience service represent the tip of the iceberg—only 1.5% of patients with TBI are treated by neurosurgeons. The effect on the young—TBI is the largest cause of disability in individuals under the age of 45—was highlighted. However, it was also noted that an increasing proportion of individuals who sustain TBI are older, in keeping with an aging population. TBI presents substantial, but different, sociological challenges in the young and old, changes life expectancies and family relationships, and can impose crippling financial burdens on individuals and their families.

Summary of discussion and recommendations for InTBIR

• Data sharing and intellectual property. To promote the involvement of pharmaceutical companies in InTBIR, strategies for sharing risks as well as benefits of successful drug development should be considered. The Innovative Medicine Initiative (http://www.imi.europa.eu/) successfully achieved this balance and may serve as an informative model.

• Involvement of regulatory agencies. The early involvement of (or communication with) regulators is desirable, in particular, if a new disease classification and new outcome measures are to be implemented in clinical studies. Participants recommended that the EMA makes available a fast-track route for TBI and other orphan conditions. In the United States, such a fast-track process is in place, but it could be streamlined for faster, more efficient implementation.

• Imaging for TBI diagnosis, prognosis, and drug development process. Modern imaging is critical for understanding the evolution of pathophysiology in TBI and, increasingly, as a diagnostic and therapy stratification tool (particularly in mTBI). However, imaging and other biomarkers need correlation with the gold standard of pathology for validation. Participants recommended that InTBIR provides an imaging platform for drug development, which would develop aspects of imaging directly relevant to the translational process.

• Outcome assessment. Variations in rehabilitation interventions (e.g., insurance limits in the United States and limited rehabilitation and follow-up in emerging countries) affect the quality of clinical care and confound outcome assessment. This variability should be taken into careful consideration when planning a clinical study.

Collecting and Sharing TBI Patient Data

Overview: Sir Graham Teasdale

The presentations focused first on new approaches for acquiring data about patients with TBI. The ways that such data might be used were then considered from clinical and physiological monitoring viewpoints, and the encouraging experience of a pilot project was presented. Several potential benefits of these approaches emerged from the ensuing discussions.

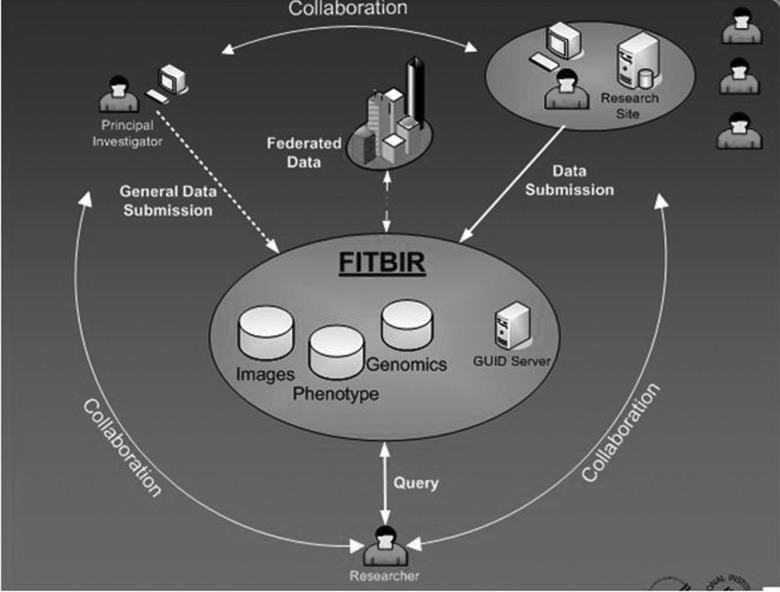

Progress toward building a federated TBI database (FITBIR): Matt McAuliffe

Limitations in current approaches to collection of data include disparate, inconsistent methods, incomplete coverage, and restricted ability to share or compare findings. The aims of FITBIR are to promote the use of consistent defined standards within a CDE approach and to develop and implement a system for storing and sharing patient-level information on phenotypic, genomic, and imaging features (Fig. 1). Key to the success of the approach will be (1) collaboration between local investigators, principal investigators, and repository managers to ensure that data are validated and deidentified, but connected by a Global Unique Identifier (GUID), (2) requirements for security, linking, and sharing by controlled access, and (3) developing the policies and governance of the system. The repository was to begin testing in November 2011 and be ready for general use in July 2012.

FIG. 1.

Main components of a federated traumatic brain injury database system.

The lessons learned from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): Ramon Diaz-Arrastia

Beginning in 2004, 58 sites in the United States and Canada have contributed data on clinical disease progression, blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples, and imaging findings in 800 people: 400 with mild cognitive impairment; 200 with Alzheimer's disease; and 200 healthy controls. Standardization of imaging information had been achieved despite the use of 89 different MRI instruments and a diversity of protocols. Open access to the data has led to impressive sharing and utilization and to more than 400 publications thus far. The lessons learned from ADNI include the following: leadership is fundamental; inclusiveness is essential for building research capacity; an open-source research model accelerates progress; and although there are difficulties, success is possible.

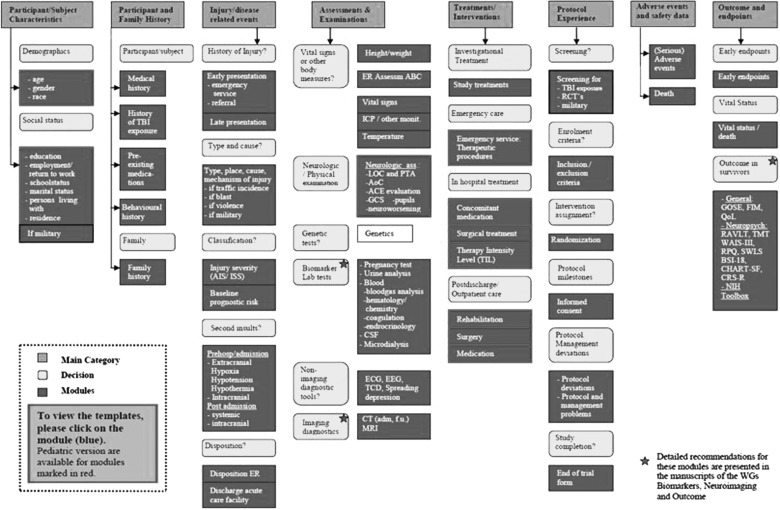

Standardized, open-access clinical data collection for the TBI community: Andrew Maas

Data standardization such as that embedded in the CDE concept is critical. The CDE structure is built around progressive elaboration of categories of Modules and Data Elements, differentiating the details of coding into Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced fields of information (http://www.tbi-impact.org and http://www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov; Fig. 2). Scientific benefits include increased comparability between studies, individual patient analysis across studies, and facilitation of clinical effectiveness research. There are also cost-efficiency benefits, including the simplification of the development of case report forms (CRFs). The CDE project is still very much in a development phase. However, software for creating an electronic CRF and a web-based data entry system has recently been developed for FITBIR. The options for data sharing include investigators being able to use their own (i.e., familiar) database structure or to have modules available within a shared database structure—visualizing only selected fields. Critical issues for successful implementation are user friendliness, flexibility, and standardization (e.g., with xml format for modules, elements, and unique identifiers). A large-scale, prospective data collection, of varying granularity, would offer a good opportunity to test and refine the flexibility and user friendliness of the system.

FIG. 2.

Generic structure of a Common Data Elements system.

Standardized, open-access data system for the intensive care unit (ICU): Ian Piper

The experience in the Brain IT project (http://ww.brainit.org) has pointed to opportunities for research and advances in care arising from improving the use of the extensive data acquired from monitoring in the ICU. Supported by the EU, units across Europe have produced standards for collection, analysis, and reporting and accumulating a database of >2 million records of periodic physiological data, thereby demonstrating feasibility of the system. These data led to new ways to investigate intracranial disorders and demonstrated how advances in data integration and analysis can yield sophisticated insights by using computer science approaches. Such data can be incorporated into an extension of the CDE, drawing on newer supportive ontology and semantic web technologies. The Avert IT project (http://www.avert-it.org), in which several centers are piloting real-time capture and sharing of high-quality data, has demonstrated feasibility of a clinical laboratory research infrastructure that can both optimize the detection of treatment effects and improve the efficiency of collecting valid, high-quality data.

Beta testing the CDEs: lessons learned from Transforming Research and Clinical Care in TBI (TRACK-TBI) study: Alex Valadka

This multi-center observational pilot study (http://www.tracktbi.net/tracktbi/), supported by the NIH, aims to assess the collection of the proposed CDEs thorough a web-based data entry system with open-source access and input. Information being collected includes the value of factors, such as biomarkers and advanced neuroimaging, for improving injury classification, a multi-dimensional approach to outcome assessment and the relation between early endpoints and outcome of care. Despite having almost 3000 fields, the CDE collection instrument has been implemented successfully in four centers and data collected within 9 months on 602 acute cases (77% with a mild injury) and on 50 patients in a rehabilitation facility. Neuroimaging protocols have been standardized and data accumulated from MRIs in 235 patients. Techniques for collecting and processing biomarkers have been established and 475 biospecimens stored. Data on 10 measures of outcome at 3 and 6 months are being obtained from most subjects. Important lessons from the success thus far include the need to secure resources for the substantial costs of recruitment, data collection and follow-up and to be receptive and flexible to accommodate the diversity of hospitals and specialities that contribute to the care of patients with TBI.

Summary of discussion and recommendations for InTBIR

• Participants agreed that there is a need to generate new data rather than continue analysis of previous data sets.

• There is also a need for an easy data entry tool, with maximum utility. The recently developed FITBIR ProForms tool may serve this purpose, but will depend on feedback from users in the future.

• The use of the TBI CDE is both desirable and feasible.

• A common repository for TBI data is both desirable and feasible.

• Several technical, operational, and conceptual issues were identified that need to be resolved. These include the need for consent from subjects to use their information, the interactions between local investigators and central coordination, data sharing, access, and ownership, quality assurance, long-term sustainability, and governance.

• The density of data collection needs to match the goals and objective of the research.

• Methods for electronic data capture and artefact rejection in the ICU need further development, along with data quality assurance, to enable accurate quantification of patient management.

Toward an Improved Injury Classification and Patient Stratification in TBI

Why we need to revise the current classification of TBI: Geoff Manley

Current approaches to rational diagnosis and targeted intervention have limitations. Clinical assessment of sTBI is increasingly difficult because of confounders (e.g., sedation, ventilation, neuromuscular blockade, and intoxicants). Genomics and comorbidities introduce additional variables that can influence outcomes. The GCS and computed tomography (CT) are commonly used to detect and stratify severity of TBI. Though the GCS retains substantial clinical utility, it does not, on its own, provide a full description of the type of injury for rational therapy selection. Instead, the GCS was developed for specific clinical purposes (i.e. “to assess depth and duration of loss of consciousness”) and was not meant to be a mechanistic diagnostic tool.14 Better insights into the extent, location, and mechanisms of tissue damage are needed in clinical practice.15 Options include a combination of imaging, biomarkers, and neurophysiology (this latter especially for mTBI). Neuropathology retains its value for understanding mechanisms of injury. To better diagnose and predict prognosis of TBI, multi-dimensional models that are valid across the broad spectrum of TBI (from concussion to coma) need to be developed. Better models would also inform the design of future clinical trials and identify new targets for therapeutic interventions.

How biomarkers can inform TBI classification: Ron Hayes

There is a growing interest in biomarkers after TBI, with new evidence rapidly accumulating. Therefore, their role, potential, and validity need refining. Biomarkers may be useful to diagnose the presence of mTBI, stratify the severity of TBI, provide early prognostic information, and/or identify the prevailing mechanisms of injury. Traditionally, biomarkers have been used to verify the presence or absence of brain damage and as an index of its severity. New data, however, indicate that specific biomarkers may be linked to specific processes. For example, alpha-spectrin breakdown products can differentiate between necrosis and apoptosis after TBI.16 The relative merits of biomarkers in CSF versus plasma need further investigation. Sample acquisition, processing, and analysis need to be conducted to high standards, and clear thresholds for abnormality should be defined. The translation from investigative to widespread clinical use also requires accurate cost-benefit analysis.

A new way to use TBI biomarkers: Olli Tenovuo

The increasing number of risk-adjustment variables that can be measured and the types and grades of intervention raise the issue of statistical rigor because consideration of all possible combinations totals 2100 possibilities. Options to address this problem include computer-aided diagnosis, decision support, and prognostication. The process would be facilitated by direct communication between the computers analyzing the data and electronic patient records. However, the automated import of physiological data, such as intracranial pressure (ICP) and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), carries a risk of being overwhelmed by artefacts. A commercial, academic (but proprietary) software solution is available that incorporates the CDEs for TBI17; the compatibility of this method with clinical monitoring devices requires further exploration.

New concepts in neuroimaging for TBI classification and monitoring: Paul Parizel

CT remains the most commonly used neuroimaging tool in sTBI and is often repeated sequentially after TBI. Nevertheless, the most appropriate protocol or scan (e.g., initial or worst CT) for research and for choice of therapy remains to be clarified. There is clearly a role for MRI, and for mTBI, it may well become the preferred option, but some concerns persist about safety in critically ill patients, especially very soon after injury when collection of sequences may be difficult. MRI may be particularly appropriate in children, because it avoids radiation exposure, but it may be difficult to ensure that they lie still unless sedation is given. Some centers have implemented ultrashort imaging protocols (<2 min), during which children are accompanied by a parent.18 Development of a head-only magnet design may also facilitate the imaging of children as well as critically ill adults. The choice of sequence(s), compatibility between different MRI device vendors, and the reading of images need to be considered. Lessons about data compatibility and sharing may be learned from the ADNI19 and from the value of central storage and analysis of images learned from several clinical trials.

Summary of discussion and recommendations for InTBIR

-

• Current approaches to rational diagnosis and targeted intervention are hampered by problems with injury characterization because of:

- Confounders in severe TBI (e.g., alcohol and sedative drugs).

- Insensitivity of conventional diagnostic methods (GCS and CT) to detect and stratify mTBI.

• An adequate description of injuries for rational therapy selection requires better insights into the extent, location, and mechanisms of tissue damage. Options include imaging (CT and MRI), biomarkers, and neurophysiology (particularly for mTBI), in combination with neuropathology, to provide robust validation.

• CSF and plasma biomarkers that could be used for diagnostic and prognostic purposes as well as for stratifying TBI patients according to injury mechanisms and/or severity are needed. For biomarker validation, it will be essential to standardize the methodology for sample acquisition, processing, analysis, and thresholds for declaring abnormality.

• Choice of imaging techniques. CT remains the initial choice in sTBI, with data from both initial and worst CT likely to contribute important information. Regarding MRI, some concerns persist about safety at early time points in sTBI and the cost of the technique. Novel developments in open magnet design might facilitate the imaging of critically ill TBI patients. On the other hand, MRI may well become the preferred option for mTBI (more sensitive than CT) and in children (it avoids radiation exposure).

There was a strong recommendation that any InTBIR-supported data collection must include central storage and analysis of images. The experience of ADNI should be taken into account to solve data compatibility and sharing issues.

Using Observational Data and Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) To Identify Best Practices and Improve Quality of Care in TBI

Benefits of CER in TBI: Geoffrey Manley

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines CER as follows: “…the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care. The purpose of CER is to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers to make informed decisions that will improve health care at both the individual and population levels.”20 The CER view of primary research is that (1) Inclusion criteria should be broad, based on the patient population implied by the clinical situation, (2) the relevant comparators are the best proven presently applied interventions, (3) the study duration should be such that the patient outcomes can be reliably assessed, and (4) studies comparing the presently applied, but never directly compared, best interventions have high value. CER encompasses the translation of clinical research to patient care, including the development of guidelines, implementation and training, capacity building, access and reimbursement, and monitoring and evaluating quality of care. CER has a natural link with personalized medicine by determining which of the interventions is best for which patients, given the situation and preferences of the patient.

Methods for bridging the gap between clinical studies and personalized medicine include using multi-variable prediction rules to relate many biomarkers simultaneously to outcome. Careful thought should be given to defining the patient population and the interventions (e.g., primary or hospital care or both, all ages or only adults, all degrees of seriousness of the situation, contraindications, and so on). Determining what health care facilities should participate in the CER for the best coverage of the patient population also needs to be carefully considered. Observational studies for CER require complete patient population databases with continuous influx, standardization, many biomarkers, and few missing data, especially outcome data. An observational database with embedded trials may be an ideal CER approach because it would produce a large, complete patient data set, including long-term outcomes, have a continuous influx of data, and it would make it possible to relate trial patients to total patient population. CER does not change the strengths and weaknesses of the study design; it only influences the choice and use of the design. Methods for indirect comparison of competing interventions should be applied to a broad framework of the patient population and include long-term outcomes. The TBI community should welcome the CER paradigm and try to contribute to its methodology and use.

Research design and analysis considerations for CER: Steve Wisniewski

There are three key components of CER, as defined by IOM (http://www.iom.edu/). The first is the aspect of “comparative research.” CER must include a direct comparison of at least two interventions, which, if one was found to be superior, would be considered the standard of care after the completion of the study. The second is the aspect of “effectiveness” research. Effectiveness research is conducted in a typical day-to-day clinical setting. Thus, the goal is to provide a more generalizable, real-world evaluation of the treatments being compared. Last, outcomes of CER are to include patient-centered outcomes, which are described as outcomes that are important to patients and typically do not involve biological markers of clinical outcomes. CER encompasses many different types of research and study designs. This may include systematic reviews of the study literature, the retrospective evaluation of large database and prospectively designed studies, such as registries, observational cohort studies, and randomized clinical trials (RCTs). To conduct CER research for treatments of TBI, researchers must first identify the clinical questions to be answered. Next, the suitability of a CER study for those clinical questions should be determined in the context of the three key components of a CER study. Finally, the most appropriate design to answer the question should be applied.

TBI: identifying and getting good practice into practice: Sir Graham Teasdale

In 1977, Jennett and colleagues21 reported wide variations in management among patients treated in the UK, Netherlands, and United States without effects on outcome. A further comparison of two participating studies in the Netherlands led Gelpke and colleagues, in 1983,22 to state, “our results do not support aspects of such an ‘aggressive’ or ‘multimodality’ management regimen to improve outcome.” Since then, reports have continued to show variations between centers,23,24 countries,25 and continents.25 Most recently, the IMPACT study, which enrolled 9578 patients, noted 3.3-fold differences in outcomes between centers after moderate and sTBI.24 The reasons for such large differences are unknown, and rigorous investigation may clarify the role of different approaches to care—including wider perspectives that are thus far little explored in TBI.

There is currently evidence from many other clinical fields of differences in the quality of “routine” care and of consequent occurrence of adverse events and poorer outcome.27 Investigations into the link between management and outcome in TBI need to consider both the role of “specific” components of care and of variations in the “general” standard of care. Information collected for CER, therefore, in addition to patient- and intervention-specific facts, needs to characterize the safety and reliability of the whole system of care. To this end, an important question is, “What indicators should we use in head injury?” ICP monitoring has been proposed as a “surrogate” quality assurance indicator,28 but it will be important to develop, validate, and apply additional indices of the quality of care provided to the patient with a TBI.

Pediatric TBI issues that could be addressed by CER: Mike Bell

TBI is the leading killer of children, with over 7000 deaths reported in the United States in 2005. In addition to this loss of life, the yearly costs of TBI on the health and welfare of children in the United States is estimated to be greater than $2 billion for acute care alone, and more than a million life-years are potentially at risk. Advances in care for children with sTBI have been disappointingly slow. RCTs of novel therapeutic agents and approaches have universally failed when applied in multiple centers. Evidenced-based guidelines are not sufficiently robust to generate meaningful recommendations because the literature has failed to demonstrate best practices for most aspects of TBI care. Variability in practices, such as intracranial hypertension control, mitigation of secondary insults, and metabolic support, are substantial in contemporary clinical practice, leading to wide variations in patient outcomes and may ultimately overwhelm treatment effects that might be observed in a well-designed RCT.

Within a consortium envisioned by the InTBIR, we propose an observational cohort study of 1000 children with sTBI to compare the effectiveness of pediatric TBI therapies from centers in the United States, Canada, UK, and EU. The aim would be to test three specific aspects that cover a total of six TBI therapies: (1) intracranial hypertension strategies—CSF diversion and hyperosmolar therapies; (2) secondary insult detection—prophylactic hyperventilation and brain tissue oxygen monitoring (PbO2); and (3) metabolic support—nutritional support and glucose management. Several statistical approaches, often used in CER to control for confounders, should be employed, including propensity score adjustments, regression analyses, and novel statistical modelling. Successful completion of this proposal would provide compelling evidence to change clinical practices, provide evidence for several new recommendations for future guidelines, and lead to improved research protocols that would limit variability in TBI treatments—helping children immediately through better clinical practices and, ultimately, through more-effective investigation.

Summary of discussion and recommendations for InTBIR

Optimum study design to advance the TBI field requires a clear, concise clinical question to be answered. In some instances, an RCT would best define the efficacy of a therapy. In other instances, an observational study, using the proper statistical design, could inform the field and generate hypotheses to be tested in further studies.

Examples of clinical questions that could be addressed by an observational study include the following:

• Understanding the natural history of TBI. Approaches should include the better stratification of injuries classified as mild based on current methodologies.

• Development of better diagnostic models of injury

• Development of better prognostic models

• Understanding “bio-signatures”; these could include serological markers along with other diagnostic tests.

• Understanding the effectiveness or efficacy of various treatments where standards have not been established

Meeting participants estimated that a sample size for such an observational study would be in the “four digit” range. Any models that were developed needed to be validated on an independent sample. Such models should explore and dissect two sources of variability. First, efforts should be made to determine the patient-specific variability that naturally exists in TBI (e.g., age, sex, race, genetics, and comorbidities). Second, efforts should be made to determine system-based variability. Potential contexts for such variability include the following:

• Clinical care (prehospital, hospital, or rehab)

• Intra- and interhospital variability

• Intra- and intercountry variability

• Quality

Linking Acute and Postacute Research

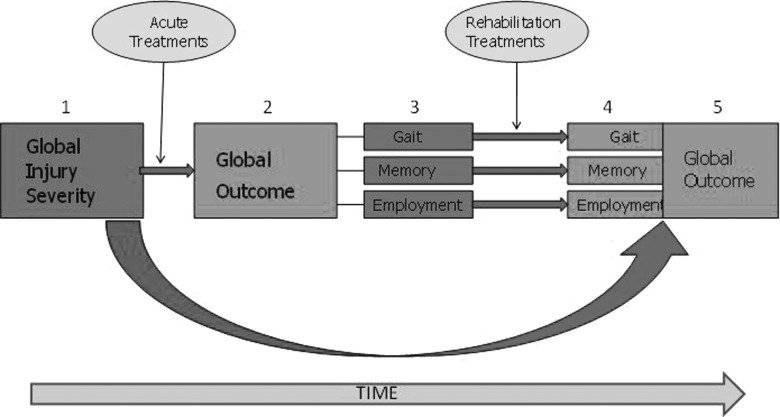

Linking acute and postacute research: Conceptual overview: John Whyte

Acute and rehabilitation studies each address two important kinds of questions: prediction of outcome and the efficacy and effectiveness of treatments. Prediction studies attempt to relate demographic and clinical patient factors to clinical and functional outcomes. Such studies control for variations in treatments that may confound this relationship. In contrast, treatment effectiveness studies control for variations in patient characteristics that directly affect outcome. Thus, both forms of research must grapple with the relationship among patient characteristics, treatments received, and outcomes achieved (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Confounds from the perspective of acute and postacute care researchers. Patient characteristics and rehabilitation interventions produce confounds to the assessment of the effectiveness of acute care interventions on long-term outcome. Initial injury characteristics (1) result in acute treatments that moderate the effect of injury and begin to influence global outcome (2), which is the product of multiple specific functional domains (here illustrated with gait function, memory ability, and employment potential; 3). Soon, one or more rehabilitation interventions are introduced, which alter one or more of these functions (4), in turn affecting long-term outcome (5).

Acute intervention after TBI generally aims to lessen the overall burden of brain damage and, consequently, a general lessening of impairment. Thus, global summary measures of function may provide reasonable outcome measures of the effectiveness of such treatments. Rehabilitation treatments generally begin soon after acute stabilization and aim to lessen the residual impairments and disabilities. However, rehabilitation interventions in patients with TBI typically have more-focused treatment goals. For example, physical therapy may concentrate on lessening contractures, improving muscle tone, and practicing basic movements for improved ambulation, whereas speech therapy may focus on oral motor control for improved swallowing function. The aggregate goal of these modalities is to improve overall self-care and mobility function. Thus, at this postacute stage, focused outcome measures may help assess the effect of individual treatments, whereas relatively global measures of function may assess their collective effect. At still later times, rehabilitation treatment may focus on more specific and limited goals, such as enhanced performance of memory-demanding tasks or improved vocational skills, and more treatment-specific outcome measures become most relevant.

Challenges in measuring outcome in TBI: Nicole von Steinbuechel

Sociodemographic, genetic, and physiologic factors that affect various aspects of outcome are available, though they continue to be refined. The CDE effort in the United States made initial recommendations for a number of measures of patient and injury characteristics, including biomarkers29,30 and imaging.31–33 Biological characteristics tend to predominate in determining early and global outcomes (e.g., GCS predicting early mortality and functional outcome), whereas a range of social and environmental factors become increasingly important predictors of postacute outcomes (e.g., previous employment history predicting return to work). Many acute interventions can be operationally defined either in specific terms (e.g., drugs and physiologic algorithms) or as adherence to broad evidence-based guidelines, but there are currently no validated taxonomies or measures of rehabilitation treatments. To date, most large rehabilitation studies have relied on crude measures of “dose” (e.g., length of stay and treatment hours) without regard to the content or active ingredients.

Linking acute and postacute care research: Recommendations from the Common Data Elements working group for TBI Outcomes: Gale Whiteneck

The CDE effort has made initial recommendations about both the outcome domains that are important to measure, informed by the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, and the specific tools that are currently recommended for measuring them. These include core measures with wide applicability (Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Trail Making Test, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III/IV, Brief Symptom Inventory-18, Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire, Functional Independence Measure-Cognitive, Functional Independence Measure-Motor, Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Tool-SF, and Satisfaction With Life Scale), supplemental measures to augment assessment of specific outcome dimensions or more-specific populations and promising tools on the horizon.34 Pediatric modifications to some of the CDEs have also been recommended to enable data collection in younger patients as well as adults.35

Selecting measures that can be used in longitudinal observational studies is challenging. Such measures need to be brief, but sufficiently comprehensive, to cover key aspects of outcome. They need to be applicable to all levels of injury severity and at as many post-traumatic stages as possible. Global and functional outcome assessment should be complemented by measures assessing cognition, as well as generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life. This can be achieved with “emerging measures” in the initial CDE recommendations. Supplementary measures of social support, important life events, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorders should also be included in a comprehensive assessment as moderator variables. The patient-reported health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures become increasingly important and measureable over time as cognitive status improves, because, in this concept, the patient is viewed as the best expert of his or her subjective health and well-being. The physical and social environment is a crucial influence on functioning, particularly at the activity and participation levels, and, most strongly, in the postacute phase. The CDE effort did not make conceptual or measurement recommendations in this area, so this is an area that requires additional development.

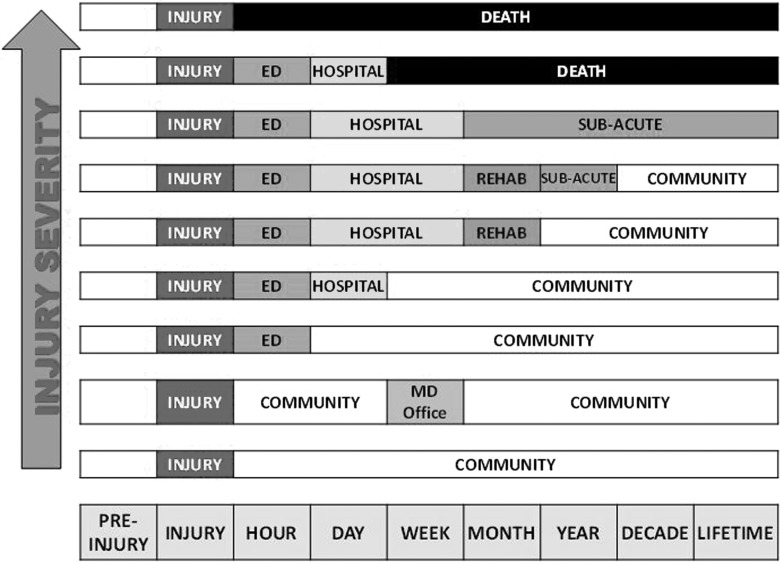

The effect of transitions in care on clinical studies: Ross Zafonte

Transitions have important implications for the linking of acute and rehabilitation treatment research. Rehabilitation interventions typically begin before the long-term effect of acute neuroprotective and neurosurgical treatment interventions can be assessed. Indeed, rehabilitation interventions are intended to minimize the effect of differences in acute neurologic factors. Thus, rehabilitation interventions unavoidably produce confounds to the assessment of the effectiveness of acute care interventions on long-term outcome, as shown in Figure 3. The relevance of acute factors to rehabilitation effectiveness research is less clear because these factors do not intervene between the rehabilitation treatment and its outcomes. Because rehabilitation treatments are typically preceded by functional assessment, early injury and treatment factors often fail to account for additional variance after inclusion of pretreatment functional measures. For example, measures of brain injury severity, such as the GCS, and duration of post-traumatic amnesia often fail to enter models where later functional variables are included. Thus, the utility of variables reflecting acute factors and treatments to the assessment of later rehabilitation treatments is an empirical question. However, accurate assessment of the efficacy of acute care interventions would benefit from the measurement of intermediate functional outcomes before delivery or rehabilitation treatments as well as accurate recording of the rehabilitation treatments received.

There are many logistical obstacles to overcome in linking acute and postacute research. Patients' acute injury severity and later functional level lead them to receive care in different service systems and, as their function changes over time, they tend to move from facility to facility or system to system (see Fig. 4). In some countries, it may be more feasible to link administrative and electronic medical record data sets over time than in others. However, there is reason to be concerned about the accuracy of treatment and outcome data recorded during the course of routine clinical care, as opposed to prospective research databases.

FIG. 4.

Treatment system transitions and injury severity.

Summary of discussion and recommendations for InTBIR

There are clear linkages between acute and postacute care. Acute care influences postacute interventions, and postacute care is a confounder of acute outcome. The participants made the following general points and recommendations:

• Clinical studies should only be initiated in high-caliber centers with research infrastructures.

• Automatic electronic data capture is not recommended for rehabilitation studies.

• We need to continue to invest in development of taxonomies for rehabilitation. Current approaches can only provide a binary description of such care (whether or not patients receive any rehabilitation). Further work may enable the time spent in rehabilitation to be quantified.

• We need to review all candidate outcome measures for language in participating countries.

• The group recognized the importance of social support and the prevailing local health care environment. We need a CDE effort on measures of environment, particularly social support.

-

• A potential CER longitudinal study supported by InTBIR should:

○ Collect biomarkers on all enrolled subjects and MRI within 1–2 weeks on all.

○ Reassess patient characteristics (medical complications, physical and cognitive function, and social support) at points of care transition so that comparable samples of patients who do or do not get the next stage of therapy are documented.

○ Document acute interventions (including early rehabilitation) and use validated patient/family interviews for quantifying the amount of rehabilitation received.

○ Collect an additional outcome measure at 1–2 weeks for out-patients and at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Research Priorities in TBI

The workshop participants identified the following key research themes that would benefit from an international collaborative effort:

• Comparative effectiveness research to determine the benefits of current and new treatments

• Prediction of outcome and how this is affected by patient, injury, and the quality of general and specific management across the continuum of care

• Development and validation of surrogate markers of injury and recovery

• A pathoanatomical and mechanistic patient classification system to enable targeted therapies

Within these themes, specific aims could be to:

• Revise concepts of injury mechanisms and classifications and validate these against neuropathological findings.

• Explore the consequences of novel classification schemes.

• Address the feasibility and benefits of individualized versus protocol-driven management in ICU.

• Examine the basis and implications of intercenter variability in management and outcome.

• Ddevelop methods for defining and measuring quality assurance and quality improvement in the care of TBI.

• Define the effects of age and the interactions of age-related cognitive changes, cerebral atrophy, and the influence of the characteristics of a brain injury.

• Enroll patients as early as possible with the aims of outcome prediction and acute treatment assessment, controlling for later rehabilitation treatment.

The InTBIR

Representatives from funding agencies and organizations* agreed that international collaboration would accelerate TBI research and discussed the framework for an international initiative in the field of TBI research. As a result, the EC, the NIH, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) expressed interest in developing a framework for an InTBIR. The initial objective of the InTBIR will be to collect standardized clinical data and build a shared database that would be later used for comparative effectiveness research. The ultimate goal of the InTBIR will be to identify effective interventions for TBI patients within the next 10 years.

The InTBIR is open to all funding agencies interested in contributing to InTBIR goals. Criteria for participation in the InTBIR will be further discussed among participating agencies, and a complete document setting InTBIR goals, governance, strategies, and rules for participation will be developed and made public in 2013.

Funding agencies will aim to coordinate research investments while working within their existing frameworks. They may publish similar calls for proposals (or other appropriate funding mechanisms) and/or use a modular approach to fund complementary research or infrastructures. Supported projects will be expected to network and collaborate. Finally, it was recommended that a governance structure similar to previous successful international consortia be established.

Summary and Recommendations

• Representatives from the European Commission, the NIH, and the CIHR agreed to work together to develop a framework for the InTBIR.

• There was a clear consensus that increased dialogue and coordination of research at international level would be beneficial for advancing TBI research, treatment, and care.

• Particular importance was given to standardizing clinical data collection and creating a shared database for future comparative effectiveness research applications because the ultimate InTBIR goal is to identify effective TBI interventions.

• The InTBIR will enable the high-priority themes and specific aims of TBI research to be connected through a broad, but coherent, fundamental purpose and strategy.

Appendix

The Workshop Participants include: David Adelson, St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona; Beth Ansel, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, Bethesda, Maryland; Mary Baker, European Brain Council, European Federation of Neurological Associations, West Sussex, UK; William Barsan, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; Michael Bell, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Andras Buki, Pecs University, Pecs, Hungary; Marie-Noelle Castel, Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France; Anne-Christine Cayssiols, Codman-Johnson & Johnson, Lyon, Rhone-Alpes, France; Philippe Cupers, European Commission, DG RTD, Brussels, Belgium; Rafael De Andres Medina, Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain; Thomas DeGraba, National Intrepid Center of Excellence, Bethesda, Maryland: Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland; Christina Duhaime, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; Per Enblad, Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden; Rita Formisano, IRCCS Santa Lucia Foundation, Rome, Italy; Sten Grillner, International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden; Magali Haas, One Mind for Research Partner of Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey; Dik Habbema, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands; Ronald Hayes, Banyan Biomarkers, Alachua, Florida; Deborah Hirtz, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland; Stuart Hoffman, Department of Veteran Affairs, Washington, DC; Andy Jagoda, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York; Ji-yao Jiang, Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China; James Kelly, National Intrepid Center of Excellence, Bethesda, Maryland; Andrew Maas, Antwerp University Hospital, Edegem, Belgium; Thomas McAllister, BHR Pharma, LLC, Herndon, Virginia; Matthew McAuliffe, National Institutes of Health, Center for Information Technology, Bethesda, Maryland; Geoffrey T. Manley, University of California, San Francisco, California; David K. Menon, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK; Pratik Mukherjee, University of California, San Francisco, California; David Okonkwo, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Paul Parizel, Antwerp University Hospital, Edegem, Belgium; Anthony Phillips, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; Ian Piper, Southern General Hospital, Glasgow, UK; Silvana Reggio, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York; Claudia Robertson, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas; Juan Sahuquillo, Vall d'Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain; Norman Saunders, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; Carlos Segovia Perez, Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain; Kevin Smith, One Mind for Research, Boston, Massachusetts; Nino Stocchetti, University of Milan, Milan, Italy; Graham M. Teasdale, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK; Nancy Temkin, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; Olli Tenovuo, Finnish Brain Injury Research and Development, Turku, Finland; Alex Valadka, Seton Brain and Spine Institute, Austin, Texas; Nicole Von Steinbuechel, Gottingen Medical University, Gottingen, Denmark; Michael Weinrich, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, Bethesda, Maryland; John Whyte, Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania; Gale Whiteneck, Craig Rehabilitation Center, Englewood, Colorado; Steve Wisniewski, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and Ross Zafonte, Harvard Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation, Boston, Massachusetts.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: and the Workshop Participants

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or any other agency of the U.S. government, the CIHR, or any other agency of the Canadian government, or the EC or any other agency of the EU.

References

- 1.Maas A.I.R. Menon D.K. Lingsma H.F. Pineda J.A. Sandel M.E. Manley G.T. Re-orientation of clinical research in traumatic brain injury: report of an international workshop on comparative effectiveness research. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:32–46. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyder A.A. Wunderlich C.A. Puvanachandra P. Gururaj G. Kobusingye O.C. The impact of traumatic brain injuries: a global perspective. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22:341–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leibson C.L. Brown A.W. Ransom J.E. Diehl N.N. Perkins P.K. Mandrekar J. Malec J.F. Incidence of traumatic brain injury across the full disease spectrum: a population-based medical record review study. Epidemiology. 2011;22:836–844. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318231d535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobsson L.J. Westerberg M. Söderberg S. Lexell J. Functioning and disability 6–15 years after traumatic brain injuries in northern Sweden. Acta. Neurol. Scand. 2009;120:389–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavett B.E. Stern R.A. McKee A.C. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a potential late effect of sport-related concussive and subconcussive head trauma. Clin. Sports Med. 2011;30:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clayton T.J. Nelson R.J. Manara A.R. Reduction in mortality from severe head injury following introduction of a protocol for intensive care management. Br. J. Anaesth. 2004;93:761–767. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein S.C. Georgoff P. Meghan S. Mizra K. Sonnad S.S. 150 years of treating severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic review of progress in mortality. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1343–1353. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulger E.M. Nathens A.B. Rivara F.P. Moore M. MacKenzie E.J. Jurkovich G.J. the Brain Trauma Foundation. Management of severe head injury: Institutional variations in care and effect on outcome. Crit. Care Med. 2002;30:1870–1876. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauer R. Steiner M. Injuries in the European Union. statistics Summary. 2009. https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/idb/documents/2009-IDB-Report_screen.pdf. [Jul 2;2013 ]. pp. 2005–2007.https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/idb/documents/2009-IDB-Report_screen.pdf

- 10.Narayan R.K. Michel M.E. Ansell B. Baethmann A. Biegon A. Bracken M.B. Bullock M.R. Choi S.C. Clifton G.L. Contant C.F. Coplin W.M. Dietrich W.D. Ghajar J. Grady S.M. Grossman R.G. Hall E.D. Heetderks W. Hovda D.A. Jallo J. Katz R.L. Knoller N. Kochanek P.M. Maas A.I. Majde J. Marion D.W. Marmarou A. Marshall L.F. McIntosh T.K. Miller E. Mohberg N. Muizelaar J.P. Pitts L.H. Quinn P. Riesenfeld G. Robertson C.S. Strauss K.I. Teasdale G. Temkin N. Tuma R. Wade C. Walker M.D. Weinrich M. Whyte J. Wilberger J. Young A.B. Yurkewicz L. Clinical trials in head injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2002;19:503–557. doi: 10.1089/089771502753754037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tolias C.M. Bullock M.R. Critical appraisal of neuroprotection trials in head injury: what have we learned? NeuroRx. 2004;1:71–79. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janowitz T. Menon D.K. Exploring new routes for neuroprotective drug development in traumatic brain injury. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010;2:27rv1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olesen J. Gustavsson A. Svensson M. Wittchen H.-U. Johsson B. the CDBE2010 Study Group and the European Brain Council. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012;19:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teasdale G. Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saatman K.E. Duhaime A.C. Bullock R. Maas A.I. Valadka A. Manley G.T the Workshop Scientific Team and Advisory Panel Members. Classification of traumatic brain injury for targeted therapies. J. Neurotrauma. 2008;25:719–738. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mondello S. Robicsek S.A. Gabrielli A. Brophy G.M. Papa L. Tepas J. Robertson C. Buki A. Scharf D. Jixiang M. Akinyi L. Muller U. Wang K.K. Hayes R.L. αII-spectrin breakdown products (SBDPs): diagnosis and outcome in severe traumatic brain injury patients. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1203–1213. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honeybul S. An update on the management of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2011;55:343–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duhaime A.C. Holshouser B. Hunter J.V. Tong K. Common data elements for neuroimaging of traumatic brain injury: pediatric considerations. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:629–633. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiner M.W. Veitch D.P. Aisen P.S. Beckett L.A. Cairns N.J. Green R.C. Harvey D. Jack C.R. Jagust W. Liu E. Morris J.C. Petersen R.C. Saykin A.J. Schmidt M.E. Shaw L. Siuciak J.A. Soares H. Toga A.W. Trojanowski J.Q. the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: a review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:S1–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.09.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine. Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. www.iom.edu/∼/media/Files/Report%20Files/2009/ComparativeEffectivenessResearchPriorities/CER%20report%20brief%2008-13-09.pdf. [Jul 2;2013 ];2009 2:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennett B. Teasdale G. Galbraith S. Pickard J. Grant H. Braakman R. Avezaat C. Maas A. Minderhoud J. Vecht C.J. Heiden J. Small R. Caton W. Kurze T. Severe head injuries in three countries. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psych. 1977;40:291–298. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.40.3.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelpke G.J. Braakman R. Habbema J.D. Hilden J. Comparison of outcome in two series of patients with severe head injuries. J. Neurosurg. 1983;59:745–750. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.59.5.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clifton G.L. Choi S.C. Miller E.R. Levin H.S. Smith K.R., Jr. Muizelaar J.P. Wagner F.C., Jr. Marion D.W. Luerssen T.G. Intercenter variance in clinical trials of head trauma—experience of the National Acute Brain Injury Study: Hypothermia. J. Neurosurg. 2001;95:751–755. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.5.0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lingsma H.F. Roozenbeek B. Perel P. Roberts I. Maas A.I.R. Steyerberg E.W. Between-centre differences and treatment effects in randomized controlled trials: a case study in traumatic brain injury. Trials. 2011;12:201. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stocchetti N. Risk prevention, avoidable deaths, and mortality-morbidity reduction in head injury. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2001;8:215–219. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200109000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hukkelhoven C.W.P.M. Steyerberg E.W. Farace E. Habbema J. D. F. Marshall L.F. Maas A.I.R. Regional differences in patient chracteristics, case management, and outcomes in traumatic brain injury: experience from the tirilazad trials. J. Neurosurg. 2002;7:549–557. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.3.0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGlynn E.A. Asch S.M. Adams J. Keesey J. Hicks J. DeCristofaro A. Kerr E.A. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;26:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maas A.I. Schouten J.W. Stocchetti N. Bullock R. Ghajar J. Questioning the value of intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring in patients with brain injuries. J. Trauma. 2008;65:966–967. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318184ee7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manley G.T. Diaz-Arrastia R. Brophy M. Engel D. Goodman C. Gwinn K. Veenstra T.D. Ling G. Ottens A.K. Tortella F. Hayes R.L. Common data elements for traumatic brain injury: recommendations from the biospecimens and biomarkers working group. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010;91:1667–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adelson P.D. Pineda J. Bell M.J. Abend N.S. Berger R.P. Giza C.C. Hotz G. Wainwright M.S. Common data elements for pediatric traumatic brain injury: recommendations from the working group on demographics and clinical assessment. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:639–653. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duhaime A.C. Gean A.D. Haacke E.M. Hicks R. Wintermark M. Mukherjee P. Brody D. Latour L. Riedy G. the Common Data Elements Neuroimaging Working Group Members and the Pediatric Working Group Members. Common data elements in radiologic imaging of traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010;91:1661–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.07.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haacke E.M. Duhaime A.C. Gean A.D. Riedy G. Wintermark M. Mukherjee P. Brody D.L. DeGraba T. Duncan T.D. Elovic E. Hurley R. Latour L. Smirniotopoulos J.G. Smith D.H. Common data elements in radiologic imaging of traumatic brain injury. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2010;32:516–543. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunter J.V. Wilde E.A. Tong K.A. Holshouser B.A. Emerging imaging tools for use with traumatic brain injury research. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:654–671. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilde E.A. Whiteneck G.G. Bogner J. Bushnik T. Cifu D.X. Dikmen S. French L. Giacino J.T. Hart T. Malec J.F. Millis S.R. Novack T.A. Sherer M. Tulsky D.S. Vanderploeg R.D. von Steinbuechel N. Recommendations for the use of common outcome measures in traumatic brain injury research. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010;91:1650–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCauley S.R. Wilde E.A. Anderson V.A. Bedell G. Beers S.R. Campbell T.F. Chapman S.B. Ewing-Cobbs L. Gerring J.P. Gioia G.A. Levin H.S. Michaud L.J. Prasad M.R. Swaine B.R. Turkstra L.S. Wade S.L. Yeates K.O. Recommendations for the use of common outcome measures in pediatric traumatic brain injury research. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:678–705. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]