Abstract

Increased access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in developing countries over the last decade is believed to have contributed to reductions in HIV transmission and improvements in life expectancy. While numerous studies document the effects of ART on physical health and functioning, comparatively less attention has been paid to the effects of ART on mental health outcomes. In this paper we study the impact of ART on depression in a cohort of patients in Uganda entering HIV care. We find that twelve months after beginning ART, the prevalence of major and minor depression in the treatment group had fallen by approximately 15 and 27 percentage points respectively relative to a comparison group of patients in HIV care but not receiving ART. We also find some evidence that ART helps to close the well-known gender gap in depression between men and women.

Keywords: HIV, Antiretroviral therapy, Mental health, Africa

Introduction

The burden of disease associated with mental disorders in developing countries is attracting increasing attention (Patel et al. 2007a; Prince et al. 2007). Recent estimates suggest that mental disorders may account for as much as 10 percent of total disease burden as measured by disability adjusted life years or DALYs (Patel 2007), and depression is ranked as one of the top ten leading causes of disease burden measured by DALYs (Lopez et al. 2006). Rates of mental illness have been shown to be particularly high among people living with HIV. A recent review estimates that the rate of mental disorders among HIV positive individuals is between 44 and 58 percent (Brandt et al. 2009). Depression appears to be the most common disorder. In sub-Saharan Africa, 10 to 20 percent of persons living with HIV have major depression and another 20 to 30 percent have elevated depressive symptoms or minor depression (Brandt 2009; Collins et al. 2006; Myer et al. 2008). Other studies have also shown higher rates of anxiety, substance use, and posttraumatic stress in people living with HIV (Sebit et al. 2003; Myer et al. 2008).

While there is a clear association between mental illness and HIV, the direction of causality is less clear. Does being infected with HIV lead to worse mental health or does the causality run in the opposite direction? Both are plausible. There is a large literature showing that individuals with mental disorders engage in higher than average rates of risky behaviors ranging from unprotected sex, to sex with multiple partners, to drug use, making them much more likely to become HIV infected (Rosenberg et al. 2001; Carey et al. 2004; Meade and Sikkema, 2005). On the other hand, HIV infection may lead to worse mental health because of direct neurological effects of the virus (Freeman et al. 2005), psychological stress induced by inability to provide for one’s family because of ill health, and the social alienation associated with stigma and discrimination (Chandra et al, 1998; Tostes et al, 2004). Numerous studies have also documented a strong correlation between poor physical health and poor mental health (Das et al. 2009; Mohanan and Maselko 2010). Because causality is likely to run in both directions, separating one from the other is empirically challenging.

To shed some light on the question of whether HIV causes mental illness, we study the effect of antiretroviral therapy (ART) on depression. If HIV causes depression, for example through its effect on physical health, then treatment with ART should lead to a decrease in depression rates. If causality runs primarily in the other direction, then ART should have little or no effect on depression. It is also theoretically possible that ART may worsen mental health, for example because of the stress associated with adherence to a daily regimen of pill taking. Some antiretroviral drugs such as efavirenz have also been found to have psychiatric side effects (Kenedi and Goforth 2011). The link between HIV and depression is of significant policy interest because depression has been linked to more rapid HIV disease progression (Antelman et al. 2007), lower adherence to HIV medication (Starace et al. 2002), and worse outcomes (Cook et al. 2004; Briongos-Figuero 2011).

The effects of ART on mental health, and in particular on depression have not been well studied. While there is no shortage of studies documenting the effects of ART on physical health and quality of life (Jahn et al. 2008; Beard et al. 2009), and on economic wellbeing (Thirumurthy et al. 2008), much less attention has been paid to the effects of ART on mental health. The available empirical evidence is mixed. While some studies have found beneficial effects (Bock et al. 2008; Jelmsa et al. 2005), others have found no effect (Freeman et al. 2007; Adewuya et al. 2007), and at least one study has found a negative effect of ART on mental health (Pearson et al. 2009). The latter study, which was situated in Mozambique, found that depressive symptoms increased after 12 months on ART. A review by Brandt et al. (2009) highlights some of the shortcomings of this literature that make it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Of the 23 studies that were reviewed, only 5 were longitudinal studies and of these, only 2 used a comparison group. This paper makes the following contributions: first we study the impact of ART on an important mental health disorder, depression, second, our panel study design with treatment and comparison groups allows for more robust identification, and third, we differentiate between impacts of ART on minor and major depression and explore whether there are heterogeneous effects by gender.

METHODS

The Study Setting

Uganda is often held up as a HIV/AIDS success story in Africa. Initially one of the highest HIV prevalence countries in the region, the 1990s saw a dramatic decline in HIV prevalence rates from a high of 18.5% in 1992 to about 5% in 2000 (Kirungi et al. 2002). This decline in prevalence has been attributed to strong proactive government leadership, an effective grassroots prevention campaign, and an open approach to managing the epidemic that helped to reduce the stigma associated with the disease (Schoepf 2003; Slutkin et al. 2006). Currently, there are an estimated 1.2 million people in Uganda living with HIV/AIDS, about 57% of whom are female, and 12.5 percent of whom are children under 15 (Uganda AIDS Commission 2012). Heterosexual transmission accounts for the vast majority (80 percent) of HIV infections in Uganda, with mother to child transmission accounting for about 20 percent of cases. There is some indication that HIV infections may be on the rise (Shafer et al. 2008) with recent estimates showing an 11 percent increase in HIV incidence from 115,775 new cases in 2007/08 to 128,980 in 2009/10.

Study Design

This study was carried out between July 2008 and October 2010 at two HIV clinics in Kampala, Uganda. Between June 2008 and April 2009, 482 eligible patients were enrolled into the study. Although statistics on study refusal were not recorded, the study interviewers indicate that nearly all clients who were eligible agreed to enroll in the study. Eligibility criteria for participation included patient type (patients new to HIV care), age (adults 18 and older), completion of an evaluation for ART eligibility, and a CD4 count < 400 cells/mm3. The latter restriction was to increase the similarity between patients in the treatment (ART) group, and patients in the comparison (non-ART) groups, since randomization was not ethical as ART was widely available at the study sites and in most of Uganda.

257 patients were eligible for ART and assigned to the treatment group, while 225 patients met study participation criteria but were not eligible for ART and were assigned to the comparison group. ART eligibility was defined based on clinical criteria (CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 or WHO Stage III/IV disease), and adherence readiness as assessed through clinic attendance and having a ‘treatment supporter’. This is typically a relative or friend who will help the patient access and adhere to treatment. Individuals are only required to identify someone who can play this role; the ‘treatment supporter’ otherwise does not play a formal role in the patient’s treatment. We also note that it is rare for patients to be refused ART because of the inability of the patient to identify a ‘treatment supporter’.

All study participants received standard HIV care, which included monitoring and treatment of infections, and prescription of appropriate prophylactic medications. Psychiatric care was not available at the study clinics during the study period, and antidepressants were not used to treat depression; however, counseling services were available to clients when requested or recommended by the provider, and generally consisted of pre- and post-HIV test counseling, ART adherence counseling, and counseling related to HIV disclosure and sexual and reproductive health issues.

Study subjects were assessed at baseline, at 6 months, and again at 12 months. Assessment consisted of a clinical assessment (opportunistic infections, medications, CD4 count), and an interviewer-administered survey. The survey collected information about patient characteristics including economic outcomes; attitudes towards treatment; adherence to medication; sexual behavior, and physical and mental health. All participants also received compensation of approximately $2.50 (6000 Uganda Shillings) after each study assessment (this is roughly equivalent to a day’s wages). The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Makerere University, College of Health Sciences and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology.

Empirical Strategy

Our objective is to estimate the impact of ART on depression. Our basic regression model is a difference-in-difference (D-in-D) linear probability model that compares the change in depression for the treatment group (individuals in the ART group) to the change in depression for the comparison group. All models are estimated on an intent-to-treat basis. The basic model takes the following form:

where Depressiona is a binary indicator for whether an individual has major depression (or minor depression in alternative specifications) at time t. Depression was assessed using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is commonly used to screen for depression in primary health care settings. It has 9 questions, each measuring the frequency of a symptom over the last two weeks using a rating scale from 0 ‘not at all‘ to 3 ‘nearly every day’, and scores are summed (the maximum possible score is therefore 27). A score of 5-9 indicates minor depression, while 10 or higher indicates major depression; within the classification of major depression are three levels of severity: moderate (scores of 10-14), moderate to severe (15-19) and severe (20 and greater) (Kroenke et al. 2001). Treatedi is an indicator for whether the individual was assigned to the ART group at baseline. Treatedi * 6 months and Treatedi * 12 months are the explanatory variables of interest. β2 and β3 represent the impact of ART on depression at 6 and 12 months respectively. X’i is a vector of baseline characteristics that include age, sex, education, marital status, health status, employment status, number of children, household size, and household wealth quintiles. We include these variables to control for baseline differences between individuals in the treatment and comparison groups. vt are the time (survey wave) dummies included to control for common time trends.

Health status was measured using the 35-item Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey or MOS-HIV (Mast et al. 2004). From the MOS-HIV we included the 6-item physical health functioning sub-scale which assesses degree of impairment in performing activities of daily life, and the overall general health scale. Scores were standardized to range from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 100, with higher scores implying better health. We control for the individual’s physical functioning and overall general health at baseline. Employment is a binary variable for whether or not the individual is employed at baseline, and education is also a binary variable for whether the individual has ever attended school. We also include a control for whether the individual reports having a regular sexual partner at baseline. About a quarter of respondents did not provide an answer to this particular question.1 We include ‘no response’ as a separate category. Other control variables have standard definitions.

In alternative models, we include person-level fixed effects to control for unobserved (and unmeasured) differences between treated and non-treated individuals. This amounts to a within-person difference. Note that once we include individual fixed effects, the baseline control variables drop out of the model because they cannot be separately identified from the individual fixed effects. Results from our regression models are reported in Tables 2-4.

Table 2.

Effect of ART on major depression

| VARIABLES | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | 0.097*** | 0.109*** | |||

| (0.024) | (0.026) | ||||

| 6 months | 0.033 | 0.035 | 0.0 27 | 0.0 37 | |

| (0.022) | (0.024) | (0.023) | (0.024) | ||

| 12 months | 0.017 | 0.031 | 0.033 | 0.068** | |

| (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.020) | (0.027) | ||

| Treated × 6 months1 | −0.131*** | −0.126*** | −0.128*** | −0 114*** | |

| (0.033) | (0.035) | (0.036) | (0.038) | ||

| Treated × 12 months2 | −0.139*** | −0.138*** | −0.146*** | −0.123*** | |

| (0.029) | (0.030) | (0.032) | (0.032) | ||

| Treated × 6 months × Female3 | −0.037 | ||||

| (0.069) | |||||

| Treated × 12 months × Female3 | −0.079 | ||||

| (0.062) | |||||

| Includes Baseline Characteristics4 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Includes Individual Fixed Effects | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Includes Health Status controls5 | No | No | No | Yes | No |

|

| |||||

| Observations | 1,1 30 | 1,1 18 | 1,1 30 | 1,1 18 | 1,1 18 |

| R-squared | 0.034 | 0.150 | 0.050 | 0.089 | 0.062 |

Dependent variable is an indicator for major depression i.e. PHQ-9 > 9. Treated is an indicator for whether the individual was in the ART group. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at individual level ***p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

This is the difference in difference estimate at 6 months i.e. the change in the dependent variable between Month 0 and month 6 for the treated group relative to the same change for the comparison group.

This is the difference in difference estimate at 12 months i.e. the change in the dependent variable between Month 0 and month 12 for the treated group relative to the same change for the comparison group.

Two-way interactions between gender and time and between gender and treatment status are included but results are omitted to save space.

Baseline characteristics include age, sex, schooling, marital status, health status, whether the patient is the household head, employment, number of children, ethnic group, religiosity, alcohol use, number of months HIV+, current partner status, household characteristics, wealth index, and interviewer fixed effects. Note that these drop out in the fixed effects specification in Columns 3-5.

These include self-reported health, MOS-HIV physical functioning score, and the MOS-HIV overall health score. We obtain similar results in alternative models in which the health variables are entered one at a time to account for possible collinearity in these variables.

Table 4.

Does controlling for attrition affect estimates? (Weighted Least Squares)

| VARIABLES | (1) Major Depression |

(2) Minor Depression |

|---|---|---|

| Treated × 6 months1 | −0 141*** | −0.186*** |

| (0.038) | (0.065) | |

| Treated × 12 months2 | −0.154*** | −0.309*** |

| (0.035) | (0.053) | |

| Includes Individual Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| 3 Includes Attrition Weights3 | Yes | Yes |

|

| ||

| Observations | 1,1 30 | 1,1 30 |

| R-squared | 0.066 | 0.151 |

Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at individual level ***p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

This is the difference in difference estimate at 6 months i.e. the change in the dependent variable between Month 0 and month 6 for the treated group relative to the same change for the comparison group.

This is the difference in difference estimate at 12 months i.e. the change in the dependent variable between Month 0 and month 12 for the treated group relative to the same change for the comparison group.

Attrition weights are inverse probability weights calculated following the procedure outlined in Fitzgerald, Gottshalk and Moffitt (1998)

Results

Our sample consists of 482 participants (257 in the treated group and 225 in the comparison group). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 34.6 years. 36 percent of respondents were male, 91 percent had some schooling, and 42 percent were married. 62 percent also reported being the head of their household and 69 percent had worked outside the home within the 7 days preceding the interview. The average participant was diagnosed as having HIV 17 months before the interview date. This is a relatively poor sample; only 49 percent reported having electricity, 66 percent did not own a TV, and 94 percent did not own either a car or a motorcycle. Not surprisingly, given the study population, 41 percent of respondents reported being in fair or poor health.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total | Treated group | Comparison group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Difference | N |

| Age | 34.60 | 8.51 | 34.84 | 8.51 | 34.32 | 8.53 | 0.52 | 482 |

| Male# | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.16 *** | 482 |

| Ever attended school# | 0.91 | 0.29 | 0.95 | 0.22 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 0.09 *** | 482 |

| Married# | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.09 * | 482 |

| Number of children | 2.98 | 2.47 | 2.60 | 2.25 | 3.42 | 2.63 | −0.83 *** | 482 |

| Attends religious service at least once a week# | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 436 |

| Respondent is Head of Household# | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 482 |

| Worked in the last 7 days# | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.44 | −0.11 *** | 482 |

| Number of rooms in house | 1.81 | 1.16 | 1.96 | 1.30 | 1.63 | 0.96 | 0.33 *** | 482 |

| Number of household members | 3.42 | 2.34 | 3.24 | 2.29 | 3.62 | 2.39 | −0.38 * | 482 |

| Number of children <5 in the household | 0.52 | 0.76 | 0.47 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.76 | −0.11 | 482 |

| Length of time in current home | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 482 |

| Electricity in home# | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.09 ** | 482 |

| Owns a TV# | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.05 | 482 |

| Owns a car or motorcycle# | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 482 |

| Number of assets currently owned | 4.73 | 2.49 | 4.86 | 2.53 | 4.59 | 2.44 | 0.27 | 482 |

| Number of months HIV+ | 16.90 | 32.34 | 12.62 | 30.59 | 21.85 | 33.65 | −9.23 *** | 477 |

| Self-reported Health Status is fair or poor# | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.15 *** | 482 |

| MOS-HIV Quality of Life Score (Scale 0-100) | 55.34 | 21.23 | 53.70 | 22.56 | 57.22 | 19.50 | −3.53 * | 482 |

| MOS-HIV General Health Score (Scale 0-100) | 41.71 | 23.43 | 40.56 | 21.53 | 43.02 | 25.42 | −2.46 | 482 |

| Any alcohol use within the last 30 days# | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.06 | 482 |

| Has a regular main sexual partner# | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 357 |

| PHQ-9 depression score (Scale 0-27) | 4.11 | 3.93 | 5.37 | 4.35 | 2.66 | 2.74 | 2.71 *** | 482 |

| Major depression (PHQ-9>9) | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.10 *** | 482 |

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Indicates a percent

In Table 1 we also compare baseline characteristics of participants in the treatment (ART) and comparison groups. We find that the treatment sample is more educated, more likely to be male, more likely to live in a house with fewer rooms, and have fewer children. They are also more likely to live in a house with electricity. Given ART eligibility criteria (CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 or WHO Stage III/IV disease), we would expect the treatment sample to be in worse health, and this is indeed the case. 48 percent of individuals in the treated group reported being in fair or poor health, compared to 33 percent of individuals in the comparison group, although a more objective assessment of health using the MOS-HIV tool shows no statistical difference between the two groups. Individuals in the treatment group were also significantly more likely to be depressed at baseline. Given their poorer health, it is not surprising that respondents in the treatment group were less likely to have worked within the preceding 7 days. Other demographic characteristics did not differ between the two groups.

Mental Health

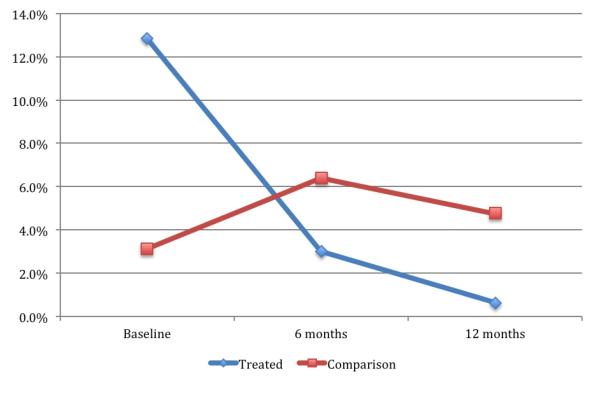

The mean PHQ-9 score for the total sample was 4.1. 29.3 percent of respondents had minor depression (5 ≤ PHQ-9 score ≤ 9), and 8.3 percent had major depression (PHQ-9 > 9). Among those with major depression, 29 (6 percent of total sample), 7 (1.5 percent), and 4 (0.8 percent) had moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively. At baseline 12.8 percent of respondents in the treated group had major depression compared to 3.1 percent in the comparison group, and 38.9 percent had minor depression in the treated group compared to 18.2 percent in the comparison group.

As a first pass at the data, in Figure 1, we plot trends in (major) depression over time for the treated and comparison group on an intention-to-treat basis. It is evident from Figure 1 that rates of depression decreased dramatically among treated individuals from 12.8 percent at baseline, to approximately 3 percent by Month 6. By Month 12, the rate of depression had fallen to nearly zero. This decrease is statistically significant (p<0.001). By contrast, in the comparison group, the rate of depression increases from 3.1 percent to 6.4 percent at Month 6, then falls slightly to 4.8 percent by Month 12. We cannot reject the null that there is no change over time (p=0.3). This first look at the data suggests a strong effect of ART on depression.

Figure 1.

Rates of Major depression over time

Next we turn to the regression results. In Table 2 Column 1, we estimate the model without any control variables, in Column 2, we include baseline characteristics as controls, and in Column 3, we include person-level fixed effects. Overall, the results are quite consistent and indicate a large effect of ART on major depression. 6 months after starting ART, the probability of major depression (a PHQ-9 score>9) falls by about 13 percentage points in the treatment group relative to the comparison group. This decrease is statistically significant (p<0.01). Given the baseline rate in the treatment group, this is a nearly 100 percent decrease. We do not find any evidence of a change in major depression for the comparison (standard HIV care) group. The coefficients indicate a small but insignificant increase. This latter result should however be interpreted with caution given the low baseline rate in the comparison group.

In Table 3, we present results for minor depression (5 ≤ PHQ score ≤ 9). According to the coefficients in our preferred specification in Column 3, individuals in the treated group experienced a 16-percentage point decrease in the probability of minor depression relative to the comparison group. This decrease is statistically significant (p<0.01). By Month 12, this difference had increased to about 27 percentage points. We are able to reject the null of equality between the 6- and 12-month coefficients (p<0.05). In alternative models where the dependent variable is the PHQ-9 score, we find similar results. These results are available from the authors on request.

Table 3.

Effect of ART on minor depression

| VARIABLES | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | 0.207*** | 0.153*** | |||

| (0.040) | (0.042) | ||||

| 6 months | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.0 36 | 0.0 41 | |

| (0.039) | (0.040) | (0.040) | (0.043) | ||

| 12 months | −0.121*** | −0 114*** | −0.101*** | −0.065 | |

| (0.031) | (0.033) | (0.033) | (0.041) | ||

| Treated × 6 months1 | −0.141** | −0.128** | −0.156** | −0.121* | |

| (0.059) | (0.060) | (0.061) | (0.063) | ||

| Treated × 12 months2 | −0.231*** | −0.226*** | −0.267*** | −0.222*** | |

| (0.047) | (0.050) | (0.053) | (0.055) | ||

| Treated × 6 months × Female3 | 0.027 | ||||

| (0.126) | |||||

| Treated × 12 months × Female5 | −0.086 | ||||

| (0.116) | |||||

| Includes Baseline Characteristics4 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Includes Individual Fixed Effects | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Includes Health Status controls5 | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Observations | 1,1 30 | 1,1 18 | 1,1 30 | 1,1 18 | 1,1 18 |

| R-squared | 0.092 | 0.186 | 0.130 | 0.157 | 0.139 |

Dependent variable is equal to 1 if 5 ≤ PHQ score ≤ 9. Treated is an indicator for whether the individual was in the ART group.

Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at individual level ***p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

This is the difference in difference estimate at 6 months i.e. the change in the dependent variable between Month 0 and month 6 for the treated group relative to the same change for the comparison group.

This is the difference in difference estimate at 12 months i.e. the change in the dependent variable between Month 0 and month 12 for the treated group relative to the same change for the comparison group.

Two-way interactions between gender and time and between gender and treatment status are included but results are omitted to save space.

Baseline characteristics include age, sex, schooling, marital status, health status, whether the patient is the household head, employment, number of children, ethnic group, religiosity, alcohol use, number of months HIV+, current partner status, household characteristics, wealth index, and interviewer fixed effects. Note that these drop out in the fixed effects specification in Columns 3-5.

These include self-reported health, MOS-HIV physical functioning score, and the MOS-HIV overall health score. We obtain similar results in alternative models in which the health variables are entered one at a time to account for possible collinearity in these variables.

The coefficients on the control variables (not shown but available on request) are broadly consistent with our expectations. We find that males were about 5 percentage points less likely to be depressed at baseline, individuals who reported working within the last 7 days were about 8 percentage points less likely to be depressed, but individuals with more children were more likely to be depressed at baseline. Consistent with the existing literature, we find a strong correlation between physical and mental health at baseline. A 10 point increase on the MOS-HIV health scale (range 0-100) was associated with a 1 percentage point decrease in the probability of being depressed at baseline, a statistically significant result. Other variables included in the model were generally insignificant.

Are there differential impacts by gender?

The previous literature has shown a gender gap in prevalence of depression and access to treatment in developing countries. Studies show that HIV positive women are significantly more likely than HIV positive men to suffer from depression (Brandt et al. 2009). We find a similar pattern in our data. At baseline, 10.4 percent of women in our sample had major depression compared to 4.6 percent of men, a statistically significant difference (p=0.027). Understanding the extent to which ART might help to close this gap is important. To explore whether there are heterogeneous impacts by gender, we estimate regressions in which we interact the two key explanatory variables, Treatedi * 6 months and Treatedi * 12 months with a dummy variable for gender. In Column 5 of Tables 2 and 3, we show the coefficients from this three-way interaction term. The results suggest that women may experience greater improvements in depression relative to men but this result is not statistically significant. Even though the coefficient is large, we cannot reject the null that it is equal to zero.

Are the effects of ART on mental health mediated by improvements in physical health?

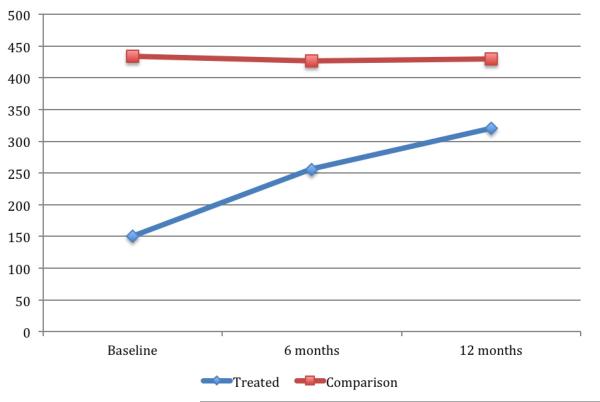

As we have previously pointed out, physical and mental health are strongly correlated (Das et al. 2009; Mohanan and Maselko 2010). It is therefore possible that the improvements in depression are as a result of improvements in physical health. To explore the potential importance of this channel with our data, we plot changes in mean CD4 cell count (as a marker for improvement in health). Not surprisingly, we find significant improvements in CD4 count for individuals receiving ART (p<0.001), but no change for individuals in the control group (p=0.93). This result should be interpreted with caution because about 20 percent of observations have missing CD4 count data. We find similar improvements in the MOS-HIV physical functioning score and the MOS-HIV overall health score. In Column 4 of Tables 2 and 3, we control for changes in these health status variables in our regression model. Even after controlling for improvements in physical health, ART still has a strong effect on depression – the magnitude of the coefficient is only reduced slightly. We obtained similar results when we controlled directly for changes in CD4 count (results available on request).

Robustness checks

Attrition

In our analyses so far, we have ignored attrition. Attrition is a concern in any longitudinal survey. When following a cohort of individuals over time, it is inevitable that some individuals will be lost to follow up because they moved, died, or because they just dropped out of the study. In our study, we started out with 482 study subjects; 143 (29.7 percent of the sample) had dropped out of the study by 6 months (90 in the treatment group and 53 in the comparison group). An additional 30 participants dropped out between 6 and 12 months (5 in the treatment group and 20 in the comparison group). First we check whether attrition was random. If attrition was random, then this presents no further problems for our analyses. If however attrition was non-random, then our estimates need to take this into account.

We estimate a probit model in which we regress a dummy for attrition on baseline characteristics (results not shown) and carry out a Wald test of joint significance of all the variables in the model. This tests whether attriters are different from attriters in observable characteristics. The Chi2-statistic from this test is 59.7 (p = 0.001), suggesting that attrition is not random.2 Attriters, for example, were more likely to attend church, have young children, and be in worse health. To correct for this, we calculate inverse probability weights following methods proposed by Fitzgerald et al. (1998). This essentially reweights the sample, giving higher weight to individuals in the sample with similar observable characteristics to those who drop out. In Table 4, we rerun the specifications in Column 3 of Tables 2-3, this time including the inverse probability weights. It is clear that our results are robust to controlling for attrition. Coefficient sizes are quite similar to those obtained from models without inverse probability weights.

Non-random treatment assignment

Another issue we address in our robustness checks is non-random treatment assignment. As is evident from Table 1, individuals assigned to the treatment (ART) group had different characteristics from those assigned to the comparison (standard care) group. Since assignment to ART was based on CD4 counts (CD4<200) and disease stage, we would expect treated individuals to be in worse health than untreated individuals. We show in Tables 2 and 3 that our results are robust to inclusion of an extensive list of baseline characteristics including baseline health status, and are also robust to the inclusion of person-level fixed effects, which control for any fixed unobservable differences between treated and non-treated individuals. As an additional robustness check, we re-estimate the results using a tighter window around the cutoff to make treated and comparison individuals more similar. When we restrict the sample to individuals with CD4 counts just above and below the cutoff – between 100 and 300, we obtain qualitatively similar results (results available on request).

Crossover

Finally we address the issue of crossover between groups. Forty-seven individuals who were not eligible for ART at baseline became eligible during the study period, effectively crossing over from control to treatment. Nine individuals also switched from treatment to control due to discontinuation of treatment. Our analysis was done on an intention-to-treat basis, meaning that an individual is “treated” or “untreated” based on treatment assignment status at baseline. Excluding individuals who ‘crossed over’ from the analysis does not change our point estimates (results available on request).

Discussion

Our results indicate that treatment with ART has a large and statistically significant effect on depression. We found that after 12 months of receiving ART, the prevalence of major depression had fallen to nearly zero in the treatment group while rates of major depression in the comparison group remained statistically unchanged. The latter result should be interpreted with caution however because of the much lower rates of major depression in the comparison group at baseline. To put our results in the context of the existing literature, our findings are broadly consistent with studies by Bock et al. (2008) who found an 83 percent reduction in depression after one year of treatment with antiretroviral drugs, and Jelmsa et al. (2005) who found a 54 percent reduction in anxiety/depression after 12 months. Another study by Wagner et al. (2012) found an 8.2 percentage point decrease in major depression in a group of HIV positive individuals being treated with ART relative to a comparison group at 12 months.

We also found a large decrease in the prevalence of minor depression in the treatment relative to the comparison group. Previous studies to our knowledge have not studied the effects of ART on minor depression. Our results indicate that ART effects may extend across a wider range of depression severity. We also found a modest decrease in rates of minor depression in the comparison group. It is possible that these modest improvements in the comparison group are due to beneficial effects of being in HIV care – as we discussed earlier, all patients (including those in the comparison group) received medical care and treatment for opportunistic infections and were also exposed to counseling. While this seems plausible, we caution that the decrease in the comparison group may simply reflect time trends. To separately identify the effects of standard care from the effect of time trends, we would need a comparison group for the comparison group, for example a group of HIV positive individuals not enrolled in a HIV clinic.

Why does treatment with ART have such dramatic impacts on depression? If the improvements in mental health are driven by improvements in physical health, one might expect that controlling for changes in health would reduce the magnitude of the treatment effect. As is evident from Column 4 in Tables 2 and 3, controlling for improvements in physical health only reduces the effect of ART on depression slightly. This suggests that ART appears to be exerting its effect largely through a channel that is separate from improvements in physical health, at least along the dimensions that we measure.

There are other reasons why ART might alleviate depression. ART effects on depression may for example operate through an increased feeling of control over one’s health. There is a literature in cognitive psychology that shows that even the semblance of control can result in improved psychological wellbeing (Lundberg et al. 2007). One could however argue that the non-ART patients were similarly taking control of their health by entering into HIV care. They just happened to be fortunate enough not to need ART at baseline. It is therefore debatable as to whether this sense of control would differ between the two groups.

Despite our best efforts, several limitations remain. First we have a high level of attrition (approximately 36 percent of the sample attrited by 12 months). This level of attrition is high but not excessively so when compared to other longitudinal studies in developing countries (Hill 2004; Alderman et al. 2001). We correct for attrition bias (assuming selection on observables) following methods outlined by Fitzgerald et al. (1998) and find, consistent with other studies, (see Alderman et al. 2001 and Falaris 2003), that attrition bias is not a serious problem. Another limitation of our study is non-random treatment assignment. We deal with this by controlling for observable differences at baseline between patients assigned to the treatment vs. comparison group. We also control for time-invariant unobservable differences by including person-level fixed effects. We show that our results are robust to both.

Finally, it is possible that our estimates are not causal. For example if patients in the treatment group were exposed to more support from clinical staff and peers, then our estimates are biased upwards because they include the effect of the additional support provided to patients receiving ART. It is not clear though that additional support can be separated from ART treatment in any meaningful way. Even if patients were randomly assigned, one might still expect differential support from clinical staff, friends and relatives. In this case, one can think of ‘ART treatment’ as a bundle i.e. ART plus support from clinical staff and others in which case, what we have estimated is the relevant parameter of interest. Note also that our difference-in-difference design assumes that the change in depression over time in the comparison group is a good representation of what would have happened in the treatment group if they had not been treated. If anything, since individuals in the treatment group were sicker to begin with, it is possible that their mental health would have declined at a faster rate than for individuals in the control group. To the extent that this is true, then we are underestimating the effect of ART.

Conclusion

Billions of dollars have been spent on improving access to ART in developing countries but it is uncommon for ART programs to include professional mental health services. Recent reports have highlighted this gap and have called for HIV treatment programs to integrate mental health identification and treatment (Freeman et al. 2005). This study documents strong beneficial effects of ART on depression. One interpretation of our results is that the relative absence of mental health care in HIV programs throughout sub-Saharan Africa may be less worrisome if ART has such a strong benefit on alleviating depression. However, it is important to recognize that the mental health benefits we observed may represent a ‘honeymoon’ effect and that over time, as physical health stabilizes and receipt of HIV care falls back into the overall context of every day life, factors influencing the presence of depression may return to the forefront. While in this study we show that beneficial effects on depression persist up to 12 months after beginning treatment, studies with longer follow up periods will be needed in order to measure long-term effects. Finally we note that we only study the effect of ART on a particular kind of mental illness, depression, and these results should not be taken as indicative of effects on other forms of mental illness. To the extent that ART does not have similar beneficial impacts on other mental disorders, professional psychiatric services will continue to be needed.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS.

This paper studies the effects of antiretroviral treatment on depression

482 HIV+ patients in 2 Ugandan clinics were enrolled (257 in the ART group and 225 in the non-ART group).

Depression was assessed at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months.

We find large beneficial effects of ART on major and minor depression.

Figure 2. Changes in Mean CD4 count over time.

Notes: Y-axis is the CD4 cell count

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child and Health Development (R24 HD056651; PI: Fred Wabwire-Mangen).

Endnotes

Interviewers were instructed to skip this question if the respondent was married or in a committed relationship, but we find that this instruction was not completely followed. 50% of married respondents for example had answers to this question (22% reported not having a regular sexual partner despite being married). It is therefore not clear what fraction of missing data is genuinely missing vs. skipped. We report it as is.

We also implement a test by Becketti et al. (1988) in which we regress depression at baseline on baseline characteristics, an attrition dummy, and interactions between the attrition dummy and baseline characteristics. We then test for joint significance of the attrition dummy and all the interaction terms. The F-statistic from this test is 1.77 (p < 0.001), implying non-random attrition.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Edward N. Okeke, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

Glenn J. Wagner, Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

References

- Adewuya A, Afolabi M, Ola B, Ogundele O, Ajibare A, Oladipo B. Psychiatric disorders among the HIV-positive population in Nigeria: A control study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007;63:203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderman H, Behrman J, Kohler HP, Maluccio JA, Watkins S. Attrition in longitudinal household survey data: Some tests from three developing countries. Demographic Research. 2001;5(4):79–124. [Google Scholar]

- Antelman G, Kaaya S, Wei R, Mbwambo J, Msamanga G, Fawzi W, et al. Depressive symptoms increase risk of HIV disease progression and mortality among women in Tanzania. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2007;44:470–477. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baingana F, Thomas R, Comblain C, HIV/AIDS and mental health . Health, Nutrition, and Population (HNP) Discussion Paper 2005. World Bank; Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- Beard J, Feeley F, Rosen S. Economic and quality of life outcomes of antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in developing countries: a systematic literature review. AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2009;21(11):1343–1356. doi: 10.1080/09540120902889926. (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becketti S, Gould W, Lillard L, Welch F. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics after Fourteen Years: An Evaluation. Journal of Labor Economics. 1988;6:472–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bock N, Lee CW, Bechange S, Moore J, Khana K, Were W, et al. Changes in depression and daily functioning with initiation of ART in HIV-infected Adults in Rural Uganda. Paper presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R. The mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: a systematic review. Afr J AIDS Res. 2009;8:123–133. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.2.1.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briongos-Figuero LS, Bachiller-Luque P, Palacios-Martin T, de Luis-Roman D, Eiros-Bouza JM. Depression and health related quality of life among HIV-infected people. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15:855–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Schroder KEE, Vanable PA, Gordon CM. HIV risk behavior among psychiatric outpatients: association with psychiatric disorder, substance use disorder, and gender. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2004;192:289–296. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120888.45094.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra PS, Ravi V, Desai A, Subbakrishna DK. Anxiety and depression among HIV-infected heterosexuals: a report from India. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1998;45(5):401–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, Homan AR, Freeman MC, Patel V. What is the Relevance of Mental Health to HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment Programs in Developing Countries? A Systematic Review. AIDS. 2006;20(12):1571–1582. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238402.70379.d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Grey D, Burke J, Cohen MH, Gurtman AC, Richardson JL, Wilson TE, Young MA, Hessol NA. Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1133–1140. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Do Q, Friedman J, McKenzie D. Mental health patterns and consequences: Results from survey data in five developing countries. The World Bank Economic Review. 2009;23(1):31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Falaris E. The Effect of Survey Attrition in Longitudinal Surveys: Evidence from Peru, Côte d’Ivoire and Vietnam. Journal of Development Economics. 2003;70:133–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J, Gottschalk, Moffit R. An analysis of sample attrition in panel data. Journal of Human Resources. 1998;33(2):251–299. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M, Patel V, Collins PY, Bertolote J. Integrating mental health in global initiatives for HIV/AIDS. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187(1):1–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M, Nkomo N, Kafaar Z, Kelly K. Factors associated with prevalence of mental disorder in people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2007;19(10):201–1209. doi: 10.1080/09540120701426482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Z. Reducing Attrition in Panel Studies in Developing Countries. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;33:493–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn A, Floyd S, Crampin AC, Mwaungulu F, Mvula H, Munthali F, et al. Population-level effect of HIV on adult mortality and early evidence of reversal after introduction of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Lancet. 2008;371:1603–1611. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60693-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelsma J, Maclean E, Hughes J, Tinise X, Darder M. An investigation into the health-related quality of life of individuals living with HIV who are receiving HAART. AIDS Care. 2005;17:579–588. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenedi CA, Goforth HW. A systematic review of the psychiatric side-effects of efavirenz. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1803–18. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9939-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirungi WL, Musinguzi JB, Opio A, Madraa E. Trends in HIV prevalence and Sexual Behaviour (1990-2000) in Uganda. International Conference on AIDS. Int Conf AIDS. 2002 Abstract no. WeOrC1269. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A, Mathers C, Ezzati M, Jamison D, Murray C. Global burden of disease and risk factors. Oxford University Press and the World Bank; Washington: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg J, Bobak M, Malyutina S, Kristenson M, Pikhart H. Adverse health effects of low levels of perceived control in Swedish and Russian community samples. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):314. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast TC, Kigozi G, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Measuring quality of life among HIV-infected women using a culturally adapted questionnaire in Rakai district, Uganda. AIDS Care. 2004;16(1):81–94. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001633994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, Sikkema KJ. HIV risk behavior among persons with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005;25:433–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanan M, Maselko J. Quasi-experimental evidence on the causal effects of physical health on mental health. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39(2):487–493. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Smit J, Le Roux L, Parker S, Stein D, Seedat S. Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: Prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22(2):147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V. Mental health in low- and middle-income countries. British Medical Bulletin. 2007:1–16. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007a;370:991–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CR, Micek MA, Pfeiffer J, Montoya P, Matediane E, Jonasse T, Cunguara A, Rao D, Gloyd SS. One year after ART initiation: Psychological factors associated with stigma among HIV-positive Mozambicans. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1189–1196. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9596-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):859–877. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Butterfield MI, Constantine NT, Wolford GL, Salyers MP. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am. J. Public Health. 2001;91:31–37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepf Brooke G. Uganda: Lessons for AIDS control in Africa. Review of African Political Economy. 2003;30:553–572. [Google Scholar]

- Sebit M, Tombe M, Siziya S, Balus S, Nkmomo S, Maramba P. Prevalence of HIV/AIDS and psychiatric disorders and their related risk factors among adults in Epworth, Zimbabwe. East African Medical Journal. 2003;80:503–512. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i10.8752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer LA, Biraro S, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Kamali A, Ssematimba D, Ouma J, et al. HIV prevalence and incidence are no longer falling in southwest Uganda: evidence from a rural population cohort 1989-2005. AIDS. 2008;22(13):1641–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830a7502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutkin G, Okware S, Naamara W, Sutherland D, Flanagan D, Carael M, et al. How Uganda reversed its HIV epidemic. AIDS Behavior. 2006;10:351–356. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starace F, Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R, De Longis P, Izzo C, et al. Depression is a risk factor for suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2002;31:S136–S139. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurthy H, Goldstein M, Graff Zivin J. The economic impact of AIDS treatment: Labor supply in western Kenya. Journal of Human Resources. 2008;43:511–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tostes MA, Chalub M, Botega NJ. The quality of life of HIV-infected women is associated with psychiatric morbidity. AIDS Care. 2004;16:177–186. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001641020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uganda AIDS Commission [Accessed September 25, 2012];Global AIDS Response Progress Report – Country Progress Report Uganda. 2012 Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2012countries/ce_UG_Narrative_Report[1].pdf.

- Wagner GJ, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Garnett J, Kityo C, Mugyenyi P. Impact of HIV antiretroviral therapy on depression and mental health among clients with HIV in Uganda. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(9):883–90. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31826629db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]