Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha (PPARα) has been demonstrated to exhibit anti-inflammatory activities that are hypothesized to play a key role in labor suppression and maintenance of uterine quiescence. The aim of this study was to identify pregnancy- and labor-associated changes in PPARα in human myometrium. For this investigation, human myometrium was obtained from premenopausal women, and the study participants were categorized into the following 4 groups: nonpregnant (NP; n = 10), preterm not in labor (PNL; n = 10, gestation range 20-35 weeks), term not in labor (TNL; n = 20, gestation range 37-41 weeks), and term in labor (TL; n = 20, gestation range 37-41 weeks). Immunohistochemistry was used to locate and confirm the expression of PPARα. Relative quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Western blotting were employed to study the expression of anti-inflammatory PPARα and proinflammatory interleukin 1β (IL-1β). Immunohistochemistry indicated that PPARα was located in the nucleus of uterine smooth muscle cells. Compared to other groups, in PNL group, the PPARα messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein increased significantly. Decreased PPARα mRNA and protein expressions in myometrium were associated with labor while IL-1β increased remarkably. There were negative correlations between PPARα and IL-1β on mRNA (r = −.765, P < .01) and protein (r = −.624, P < .01) levels analyzed using Pearson test. In conclusion, human pregnancy is associated with changes in expression of PPARα and IL-1β in myometrium. The changes observed suggest that PPARα may play a role in maintaining pregnancy or initiating labor through inhibiting the expression of IL-1β in human myometrium.

Keywords: pregnancy, myometrium, labor onset, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha, interleukin 1β

Introduction

Human pregnancy and labor are complex physiological evens. Despite impressive progress in scientific research on reproduction, the mechanisms that maintain pregnancy and initiate labor are not fully understood. Inflammation reactions with the release of cytokines are among the most accepted theories for labor.1–3 Although the role of peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor alpha (PPARα) in human parturition remains to be elucidated, PPARα has been demonstrated to exhibit anti-inflammatory activities and therefore hypothesized to play a role in labor suppression and maintenance of uterine quiescence.4–6

The PPARα is a nuclear receptor activated by natural ligands, such as fatty acids, and by synthetic ligands, such as fibrates. The PPARα exerts lipid metabolism, fatty acid oxidation, glucose homeostasis, and anti-inflammatory effects which may also play a role in pregnancy and parturition.7–11 The PPARα activation has been reported to induce the production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), increasing NO levels and inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 expression and secretion,12,13which could maintain uterine quiescence. In the absence of PPARα, mice have a prolonged response to inflammatory stimuli, increasing the secretion of interleukin (IL)-6.14 In human aortic smooth muscle cells, PPARα inhibits IL-1β-induced expression of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 via the interference of nuclear factor κ-B (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) pathways.15 Data from PPARα knockout mice suggested that PPARα maintained pregnancy by stimulating a Th2 cytokine response.16 In the choriodecidua, expression of PPARα declined with the onset of labor in normal pregnancy.17 Definitive date, however, is lacking with dynamic expression of PPARα in human pregnant smooth muscle cells.

The onset of labor requires a switch from the anti-inflammatory uterine state to an active and proinflammatory environment caused by increasing the proinflammatory mediators such as IL-1β. Interleukin 1β can activate NF-κB, thereby perpetuating the uterine inflammatory response18 and stimulating myometrial contractility.19

The first purpose of this investigation was to determine the cellular location of PPARα in human nonpregnant (NP) and pregnant myometrium. Having confirmed the presence of PPARα, the next aim of this study was to explore pregnancy- and labor-associated changes in anti-inflammatory PPARα and proinflammatory IL-1β in NP, preterm not in labor (PNL), term not in labor (TNL), and term in labor (TL) women.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Collection

Sixty women were recruited in the study and completed informed consent forms. The study design was approved by the Qilu Hospital Ethical Committee on human research. Women with pregnancy complications such as pregnancy-induced hypertension and diabetes or any other medical problem that would predispose them to an alteration in their immune response such as nephritis and systemic lupus erythematosus were excluded from the study.

The NP myometrial samples (n = 10) were collected from premenopausal women, at hysterectomy or hysteromyomectomy. The pregnant uterine samples were obtained from patients undergoing caesarean section (CS) in the following groups: PNL (n = 10, gestation range 20-35 weeks), TNL (n = 20, gestation range 37-41 weeks), and TL (n = 20, gestation range 37-41 weeks). These myometrial samples were collected from the upper middle margin of lower uterine segment incision. Indications for CS included breech presentation, fetal distress, previous section, placenta previa, failure to progress, or maternal request. Labor was defined as regular contractions (at least lasting 30 seconds per 3-5 minutes) and cervical dilatation ≥3 cm. The patient groups were controlled for differences in maternal age, height, and parity. Before surgery, no women showed signs of infection (body temperature ≤37.3°C, C-reactive protein level in patient serum ≤10mg/L, white blood cells ≤10 × 109/L). The tissue specimens were cleared of defilement. Part of the specimens were immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Western blotting, and the remaining parts were fixed in 4% formaldehyde at room temperature overnight for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

After fixing, the samples were embedded in paraffin wax and sections of 5-μm were cut. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated through graded alcohol. Then an antigen retrieval procedure was performed by boiling the sections for 20 minutes in citrate buffer (pH 6.0), in a microwave oven. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 minutes. After 3 rinses using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the sections were blocked with normal goat serum for 30 minutes in room temperature to suppress the nonspecific background staining. Rabbit polyclonal antibody to PPARα (ab8934; Abcam, Hong Kong, China; diluted 1:75) was applied to the sections overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with biotinylated goat antirabbit immunoglobulin G for 30 minutes at 37°C and then processed according to the SP kit (SP-9001; Zhongshan, Beijing, China) protocol. Negative control slides, where primary antibody was replaced with normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) serum, were also included. Sections were then photographed with an Olympus DP72 camera (Tokyo, Japan).

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcriptase Reaction

Total RNA was isolated from human myometrium by TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted RNA was dissolved in a final volume of 20-μL RNase-free water and concentrations of RNA were assessed using a spectrophotometer (smartspec plus; Bio-Rad, Hercules, California). The OD260/280 of the total RNA samples ranged between 1.8 and 2.0. Messenger RNA, 2-μg, was used for reverse transcription in a final volume of 20-μL, using RevertAid First Strand complementary DAN (cDNA) Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, the Republic of Lithuania), including 4-μL of 5× reaction buffer, 1-μL RNase inhibitor, 2-μL dNTP mix (10 mmol/L), 1-μL reverse transcriptase, and 1-μL Oligo(dt)18 in a thermal cycler (42°C for 1 hour, and 70°C for 10 minutes). The cDNA samples were stored at −20°C before analysis.

Real-Time PCR Analysis of PPARα and IL-1β mRNA

Primers were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software and chemically synthesized (Shanghai Biosune Biotechnology). The primers used were as followed, PPARα: forward, 5′-GGCCAGAGATTTGAGATCTGC-3′, reverse, 5′-ACAACGCGATTCGTTTTGGA-3′; IL-1β: forward, 5′-ACAGATGAAGTGCTCCTTCCAG-3′, reverse, 5′-CAGCATCTTCCTCAGCTTGTC-3′; β-actin: forward, 5′-TGACGTGGACATCCGCAAAG-3′, reverse, 5′-CTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGAGG -3′. Complementary DNA, 50 ng, in a 20-μL volume was used for real-time PCR with the SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix kit (Bio-Rad). The PCR was performed in triplicate using a MyiQ single-color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). The reaction conditions were 30 seconds at 95°C followed by 45 cycles of 5 seconds at 95°C, and 10 seconds at 56°C. Specific PCR products were analyzed by running melting curve and visualized by agarose electrophoresis. Quantitative values were obtained from the threshold cycle (CT) value. The housekeeping gene β-actin was used as an internal control. Relative mean fold change expression ratios were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method with the NP group as the calibrator.20

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins extracted from human myometrium were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBS-T) for 2 hours at room temperature, then washed in TBS-T 3 times for 10 minutes and incubated with the primary antibodies against PPARα (Abcam, diluted 1:1000), IL-1β (Abcam, diluted 1:150), and β-actin (Zhongshan, diluted 1:1000) overnight at 4°C. The blots were washed with TBS-T and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Zhongshan, diluted 1:5000) for 1 hour at room temperature. After 3 washes in TBS-T, the membranes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence plus reagents (Millipore, Boston, Massachusetts). Densitometry values were measured using Quantity One software. Protein expression was calculated as a ratio and β-Actin was a normalization control.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). SPSS17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) was used for statistical analysis. Comparisons among groups involved analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Student-Newman-Keuls method to determine the differences between groups. Pearson test was used to analyze the correlation between PPARα and IL-1β expression. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1 and were similar in all groups except gestational age. In the TL group, the average length of labor at the time of CS surgery was 10.19 ± 1.24 hours (time range: 8.50-12.33 hours) and the average cervical dilatation was 5.60 ± 2.04 cm (dilatation range: 3-10 cm).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Study Groups

| NP | PNL | TNL | TL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 10 | 10 | 20 | 20 |

| Age, mean (range) | 33 (26-40) | 31 (23-39) | 30 (20-39) | 29 (24-38) |

| Gestational age in days, mean (range) | 206 (142-250) | 274 (266-289) | 277 (261-287) | |

| Parity, mean (range) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-4) | 1 (0-4) |

Abbreviations: NP, nonpregnant; PNL, preterm not in labor; TNL, term not in labor; TL, term in labor.

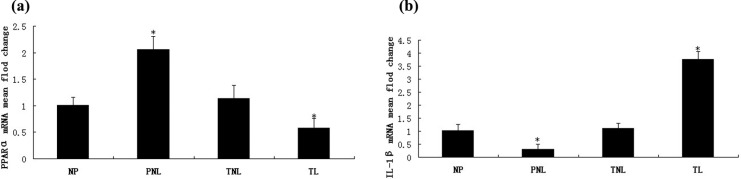

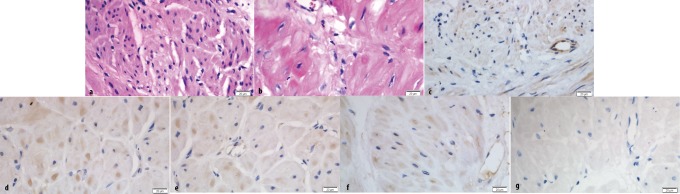

Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining was performed to determine histopathological change, and immunohistochemistry was used to identify the cellular localization of PPARα in human myometrial tissues. Staining with HE indicated hypertrophy of uterine smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in pregnancy (Figure 1B) compared with NP myometrium (Figure 1A). The PPARα was identified in NP, PNL, TNL, and TL muscle tissues with staining mainly in the uterine SMCs and to some degree within the endothelial cells of vessels (Figure 1C-F). The PPARα staining was primarily located in the nucleus of these cells.

Figure1.

Immunohistochemistry of PPARα protein in human myometrial tissue. (A) and (B) show HE staining of nonpregnant and pregnant uterine smooth muscle cells, respectively. Immunohistochemistry study of PPARα (C) in nonpregnant, (D) in preterm not in labor, (E) in term not in labor, and (F) in term labor. (G) the negative for staining with normal rabbit IgG. A nuclear yellow-brown stain indicated a positive result. Original magnification is ×400.. HE indicates hematoxylin–eosin; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

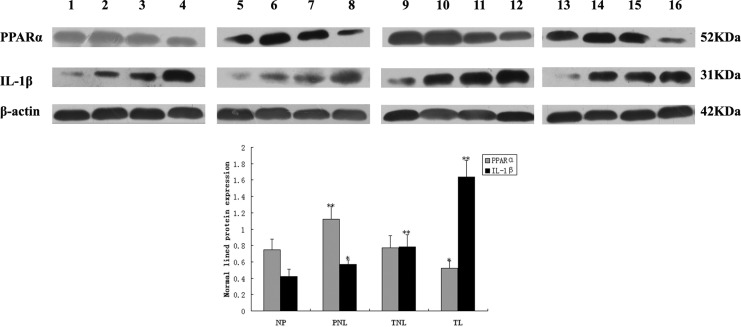

To determine the effect of pregnancy on PPARα and IL-1β mRNA expression, real-time PCR was performed on mRNA extracted from myometrium samples from women in NP, PNL, TNL, and TL groups. Melting curve analysis revealed a single peak in each sample, and agarose electrophoresis generated expected PCR products with a single band at 119, 145, and 205 bp for PPARα, IL-1β, and β-actin, respectively. Compared to other groups, the expression of PPARα in PNL group was significantly higher (P < .01), however, the expression in group TL was remarkably lower than NP, PNL, and TNL groups (Figure 2A). The expression of IL-1β in PNL group was much lower than the other 3 groups (P < .01), but when IL-1β mRNA levels from TL women were compared to NP, PNL, and TNL groups, significant increase in mRNA expression was detected (Figure 2B). No significant difference could be seen in the comparison of NP with TNL on PPARα and IL-1β mRNA expressions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative expressions of PPARα and IL-1β mRNA. Relative mean fold change expression ratios were calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method using the NP group as the calibrator and the housekeeping gene β-actin was used as an internal control. (A) Comparison of mRNA levels for PPARα. (B) Comparison of mRNA levels for IL-1β. *P < .05 versus NP. PPARα indicates peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha; IL-1β, interleukin 1β; mRNA, messenger RNA; NP, nonpregnant; PNL, preterm not in labor; TNL, term not in labor; TL, term in labor.

Western blotting analysis showed expressions of PPARα and IL-1β protein in NP, PNL, TNL, and TL myometrium (Figure 3). The PPARα, IL-1β, and β-actin had a molecular mass of 52, 31, and 42 kDa, respectively. The PPARα protein from PNL women revealed significantly higher expression compared to NP, TNL, or TL women, whereas the expression in TL group was the lowest among the 4 groups. However, there was no change in PPARα protein between NP and TNL groups. With the growth of gestational age, IL-1β protein expression was increased gradually from NP, PNL, to TNL women, and the expression in TL was the highest.

Figure 3.

The protein expressions of PPARα and IL-1β analyzed by Western blotting. 1, 5, 9, and 13 samples were from the NP group; 2, 6, 10, and 14 samples were from the PNL group; 3, 7, 11, and 15 samples were from the TNL group; and 4, 8, 12, and 16 samples were from the TL group. β-Actin was a normalization control and date was expressed as mean ± SD of relative band density. *P < .05 versus NP; **P < .01versus NP. PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha; IL-1β, interleukin 1β; NP indicates nonpregnant; PNL, preterm not in labor; TNL, term not in labor; TL, term in labor; SD, standard deviation.

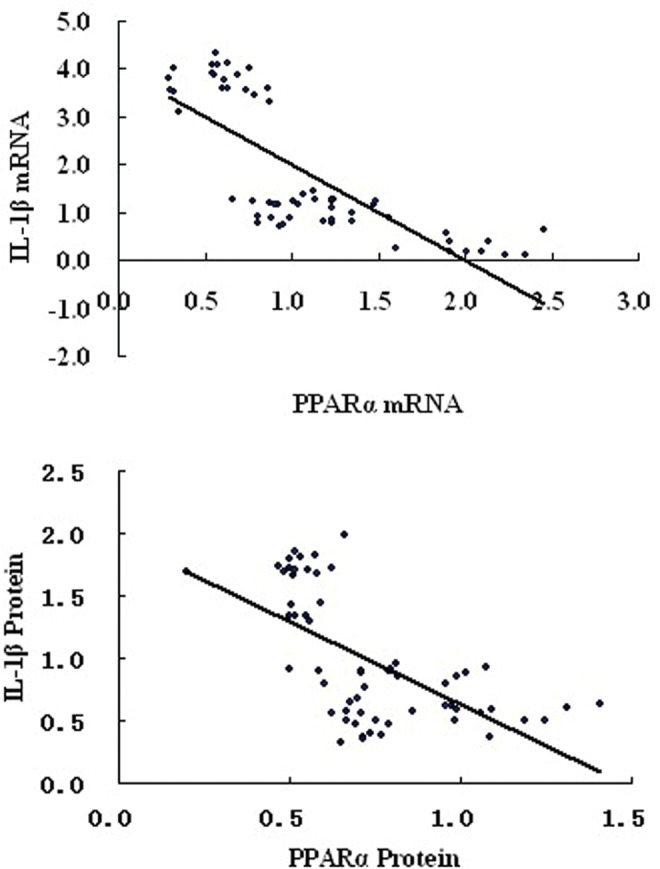

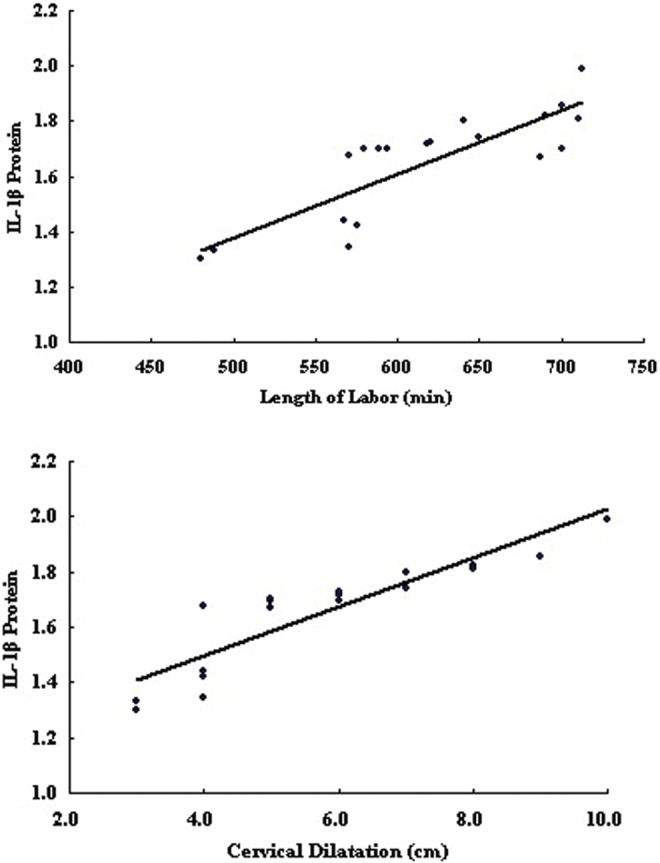

There was a significant negative correlation between PPARα and IL-1β mRNA expression (r = −.765, P < .01) and on protein level (r = −.624, P < .01; Figure 4). The PPARα mRNA and protein were highly correlated and positively associated (r = .769, P < .01). The IL-1βmRNA and protein also showed significant correlation (r = .917, P < .01). There were no statistically significant correlations between length of labor or cervical dilatation and PPARα on mRNA (r = −.083, P = .728; r = −.206, P = .384) and protein (r = −.183, P = .440; r = .079, P = .740) levels. Additionally, there were no significant differences between the length of labor or cervical dilatation and IL-1β mRNA expression (r = .112, P = .638; r = .292, P = .212), however, the length of labor and cervical dilatation were significantly correlated with IL-1β protein (r = .858, P < .01; r = .879, P < .01; Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Correlation of PPARα with IL-1β on mRNA (r = −.765, P < .01) and protein (r = −.624, P < .01) levels. PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha; IL-1β, interleukin 1β.

Figure 5.

Correlation of length of labor and cervical dilatation with IL-1β protein (r = .858, P < .01; r = .879, P < .01). IL-1β indicates interleukin 1β.

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated that PPARα is expressed in human NP, PNL, TNL, and TL myometrium tissues. We have also noted that variations in PPARα and IL-1β expression are associated with the status of pregnancy and labor.

Human pregnancy and labor are complex physiological events including tolerating and nourishing the fetal, remodeling and dilating of the cervix, rupture of the fetal membranes, and onset and maintenance of the effective uterine contractions, culminating in expulsion of the fetus and placenta. The entire process is followed by involution of the uterus.21 To reveal the biochemical process that switches the myometrium from a quiescence to an active contractive state is very important for understanding the mechanism underlying human labor.22

In this study, PPARα was confined to the nucleus of uterine SMCs and vascular endothelial cells in human uterus. Until very recently, no data were available on the cellular localization of PPARα in human myometrium. Although PPARα protein in uterine SMCs has been identified by Western blotting,23 this is the first time for it has been localized in uterus by immunohistochemistry. Additionally, we also found the hypertrophy of uterine SMCs in pregnancy which may be a response to the biological mechanical stretch of uterine walls by the growing fetus and endocrine factors.24–26

We found PPARα mRNA and protein significantly increased in the myometrium of PNL group, supporting the hypothesis that PPARα is involved in facilitating uterine quiescence.5 Bogacka27 also found that in early pregnancy compared to estrous cycle, PPARα mRNA was markedly higher in porcine endometrial tissue. The increased expression of PPARα may be important for mediating anti-inflammatory uterine quiescence and labor suppression during early and mid-trimester pregnancy. Activation of PPARα reduces the levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and COX-2 by inhibiting the translocation of NF-κB and decreasing the phosphorylation of AP-1.28,29 Reduced maternal PPARα expression would disturb Th1:Th2 ratio, increasing interferon gamma (IFNr) and decreasing IL-10 levels and could contribute to pregnancy complications such as maternal abortion and neonatal mortality.16,30 Myometrium PPARα, both mRNA and protein, decreased significantly with labor onset in our study, although we showed no difference in the PPARα expression with progressive cervical dilatation and ongoing labor. Perhaps decreased mRNA and protein expression of anti-inflammatory factor PPARα in uterine SMCs with parturition is important for initiating labor as it would reduce the suppression of IL-1β and COX-2 expression and promote uterine contractions consequently. Berry et al17 reported that there was a decrease in PPARα mRNA in choriodecidua after labor and delivery, while Holdsworth-carson et al4 found that PPARα was unchanged between different labor stages in fetal membrane in both whole cell and nuclear protein extracts. However, Holdsworth-carson et al4 also suggested PPARα DNA binding activity was down regulated during active labor in human gestational tissues. Unfortunately, we have not been able to extract nuclear protein for PPARα Western blotting and measure PPARα transcriptional activity due to the limited myometrial tissues.

This study, for the first time, investigated IL-1β expression in the myometrial of PNL women. In the PNL group, the mRNA expression of IL-1β was obviously lower than the other groups, while the protein expression was higher than the NP group. The detection of increasing protein level of IL-1β compared to the decreased mRNA demonstrates that the increased IL-1β protein may be in part synthesized within the SMCs of human uterine. Part of this protein could be produced elsewhere and has been transported here through cytokine influx.31–33 Elevated IL-1β mRNA and protein expressions in myometrium were associated with being in labor. Increasing levels of IL-1β mRNA and protein in human lower uterine segment from late pregnancy to labor onset have also been demonstrated.31,34–36 The increased IL-1β is crucial for parturition. Tribe et al19 have suggested that IL-1β enhances basal and store operated calcium entry in uterine smooth muscle cells, thus directly increasing their contractile potential. Interleukin 1β also stimulates arachidonic acid release and expression of COX-2 via greater NF-κB activity, thus increasing prostaglandin production, a potent stimulator of myometrial contractions.14,37–39 Additionally, we found that the length of labor and cervical dilatation were significantly correlated with IL-1β protein. The significant tendency toward higher IL-1β protein expression, not the mRNA, with ongoing labor and cervical dilatation might also demonstrate that the increased IL-1β protein was in part synthesized within human myometrium and another part might stem from cytokine influx in circulation during parturition.31–33,36

In addition, we found a negative correlation between PPARα and IL-1β on both mRNA and protein levels, suggesting that in human uterine SMCs, PPARα might also reduce the expression of IL-1β to maintain pregnancy.

In summary, we have found human pregnancy and labor are associated with changes in expression of PPARα and IL-1β in uterine SMCs. Our findings support the hypothesis that human parturition is an inflammatory event, and anti-inflammatory PPARα may play a role in labor suppression and maintenance of uterine quiescence. However, the question whether the decrease in PPARα mRNA and protein levels is a cause or consequence of labor still remains unanswered. The exact mechanism that regulates PPARα expression in human myometrium during the events of pregnancy and labor remains to be elucidated in future studies.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by State Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China [81170275].

References

- 1. Rinaldi SF, Hutchinson JL, Rossi AG, Norman JE. Anti-inflammatory mediators as physiological and pharmacological regulators of parturition. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7(5):675–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kamel RM. The onset of human parturition. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(6):975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Catalano RD, Lannagan TR, Gorowiec M, Denison FC, Norman JE, Jabbour HN. Prokineticins: novel mediators of inflammatory and contractile pathways at parturition? Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16(5):311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holdsworth-Carson SJ, Permezel M, Riley C, Rice GE, Lappas M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and retinoid X receptor-alpha in term human gestational tissues: tissue specific and labour-associated changes. Placenta. 2009;30(2):176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wieser F, Waite L, Depoix C, Taylor RN. PPAR Action in human placental development and pregnancy and its complications. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:527048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Froment P, Gizard F, Defever D, Staels B, Dupont J, Monget P. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in reproductive tissues: from gametogenesis to parturition. J Endocrinol. 2006;189(2):199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pyper SR, Viswakarma N, Yu S, Reddy JK. PPARalpha: energy combustion, hypolipidemia, inflammation and cancer. Nucl Recept Signal. 2010;8:e002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kwak-Kim J, Yang KM, Gilman-Sachs A. Recurrent pregnancy loss: a disease of inflammation and coagulation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35(4):609–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Challis JR, Lockwood CJ, Myatt L, Norman JE, Strauss JF, 3rd, Petraglia F. Inflammation and pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2009;16(2):206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zandbergen F, Plutzky J. PPARalpha in atherosclerosis and inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771(8):972–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Devchand PR, Keller H, Peters JM, Vazquez M, Gonzalez FJ, Wahli W. The PPARalpha-leukotriene B4 pathway to inflammation control. Nature. 1996;384(6604):39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eberhardt W, Akool el S, Rebhan J, et al. Inhibition of cytokine-induced matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha agonists is indirect and due to a NO-mediated reduction of mRNA stability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):33518–33528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shu H, Wong B, Zhou G, et al. Activation of PPARalpha or gamma reduces secretion of matrix metalloproteinase 9 but not interleukin 8 from human monocytic THP-1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267(1):345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Molnar M, Romero R, Hertelendy F. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor stimulate arachidonic acid release and phospholipid metabolism in human myometrial cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(4):825–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Staels B, Koenig W, Habib A, et al. Activation of human aortic smooth-muscle cells is inhibited by PPARalpha but not by PPARgamma activators. Nature. 1998;393(6687):790–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yessoufou A, Hichami A, Besnard P, Moutairou K, Khan NA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha deficiency increases the risk of maternal abortion and neonatal mortality in murine pregnancy with or without diabetes mellitus: Modulation of T cell differentiation. Endocrinology. 2006;147(9):4410–4418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berry EB, Eykholt R, Helliwell RJ, Gilmour RS, Mitchell MD, Marvin KW. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor isoform expression changes in human gestational tissues with labor at term. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64(6):1586–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayden MS, West AP, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB and the immune response. Oncogene. 2006;25(51):6758–6780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tribe RM, Moriarty P, Dalrymple A, Hassoni AA, Poston L. Interleukin-1beta induces calcium transients and enhances basal and store operated calcium entry in human myometrial smooth muscle. Biol Reprod. 2003;68(5):1842–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Golightly E, Jabbour HN, Norman JE. Endocrine immune interactions in human parturition. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;335(1):52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(5):514–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindstrom TM, Bennett PR. 15-Deoxy-{delta}12,14-prostaglandin j2 inhibits interleukin-1{beta}-induced nuclear factor-{kappa}b in human amnion and myometrial cells: mechanisms and implications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3534–3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shynlova O, Kwong R, Lye SJ. Mechanical stretch regulates hypertrophic phenotype of the myometrium during pregnancy. Reproduction. 2010;139(1):247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shynlova O, Oldenhof A, Dorogin A, et al. Myometrial apoptosis: activation of the caspase cascade in the pregnant rat myometrium at midgestation. Biol Reprod. 2006;74(5):839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Douglas AJ, Clarke EW, Goldspink DF. Influence of mechanical stretch on growth and protein turnover of rat uterus. Am J Physiol. 1988;254(5 pt 1):E543–E548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bogacka I, Bogacki M. The quantitative expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) genes in porcine endometrium through the estrous cycle and early pregnancy. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62(5):559–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramanan S, Kooshki M, Zhao W, Hsu FC, Robbins ME. PPARalpha ligands inhibit radiation-induced microglial inflammatory responses by negatively regulating NF-kappaB and AP-1 pathways. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(12):1695–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crisafulli C, Cuzzocrea S. The role of endogenous and exogenous ligands for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-alpha) in the regulation of inflammation in macrophages. Shock. 2009;32(1):62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mikael LG, Pancer J, Wu Q, Rozen R. Disturbed one-carbon metabolism causing adverse reproductive outcomes in mice is associated with altered expression of apolipoprotein AI and inflammatory mediators PPARalpha, interferon-gamma, and interleukin-10. J Nutr. 2012;142(3):411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Osman I, Young A, Ledingham MA, et al. Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9(1):41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Young A, Thomson AJ, Ledingham M, Jordan F, Greer IA, Norman JE. Immunolocalization of proinflammatory cytokines in myometrium, cervix, and fetal membranes during human parturition at term. Biol Reprod. 2002;66(2):445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomson AJ, Telfer JF, Young A, et al. Leukocytes infiltrate the myometrium during human parturition: further evidence that labour is an inflammatory process. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(1):229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Winkler M, Fischer DC, Ruck P, Horny HP, Kemp B, Rath W. Cytokine concentrations and expression of adhesion molecules in the lower uterine segment during parturition at term: relation to cervical dilatation and duration of labor. [in German]. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 1998;202(4):172–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winkler M, Fischer DC, Hlubek M, van de Leur E, Haubeck HD, Rath W. Interleukin-1beta and interleukin-8 concentrations in the lower uterine segment during parturition at term. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(6):945–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maul H, Nagel S, Welsch G, Schafer A, Winkler M, Rath W. Messenger ribonucleic acid levels of interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 in the lower uterine segment increased significantly at final cervical dilatation during term parturition, while those of tumor necrosis factor alpha remained unchanged. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;102(2):143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zaragoza DB, Wilson RR, Mitchell BF, Olson DM. The interleukin 1beta-induced expression of human prostaglandin F2alpha receptor messenger RNA in human myometrial-derived ULTR cells requires the transcription factor, NFkappaB. Biol Reprod. 2006;75(5):697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rauk PN, Chiao JP. Interleukin-1 stimulates human uterine prostaglandin production through induction of cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2000;43(3):152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Belt AR, Baldassare JJ, Molnar M, Romero R, Hertelendy F. The nuclear transcription factor NF-kappaB mediates interleukin-1beta-induced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human myometrial cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(2):359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]