Abstract

Background

Homeless persons experience excess mortality, but U.S.-based studies on this topic are outdated or lack information about causes of death. No studies have examined shifts in causes of death for this population over time.

Methods

We assessed all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates in a cohort of 28,033 adults aged 18 years or older who were seen at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program between January 1, 2003, and December 31, 2008. Deaths were identified through probabilistic linkage to the Massachusetts death occurrence files. We compared mortality rates in this cohort to rates in the 2003–08 Massachusetts population and a 1988–93 cohort of homeless adults in Boston using standardized rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

1,302 deaths occurred during 90,450 person-years of observation. Drug overdose (n=219), cancer (n=206), and heart disease (n=203) were the major causes of death. Drug overdose accounted for one-third of deaths among adults <45 years old. Opioids were implicated in 81% of overdose deaths. Mortality rates were higher among whites than non-whites. Compared to Massachusetts adults, mortality disparities were most pronounced among younger individuals, with rates about 9-fold higher in 25–44 year olds and 4.5-fold higher in 45–64 year olds. In comparison to 1988–93, reductions in HIV deaths were offset by 3- and 2-fold increases in deaths due to drug overdose and psychoactive substance use disorders, resulting in no significant difference in overall mortality.

Conclusions

The all-cause mortality rate among homeless adults in Boston remains high and unchanged since 1988–93 despite a major interim expansion in clinical services. Drug overdose has replaced HIV as the emerging epidemic. Interventions to reduce mortality in this population should include behavioral health integration into primary medical care, public health initiatives to prevent and reverse drug overdose, and social policy measures to end homelessness.

BACKGROUND

An estimated 2.3–3.5 million Americans experience homelessness annually,1 and over 649,000 are homeless on a single night.2 Homeless individuals have a high prevalence of physical illness, psychiatric disease, and substance abuse,3–5 contributing to very high mortality rates in comparison to non-homeless people.6–17

Despite the persistence of homelessness in the U.S., the past decade has yielded few studies on mortality among homeless Americans, and information on causes of death in this population is sparse. In the most recent study that examined causes of death in a U.S.-based homeless population, Hwang and colleagues analyzed data on 17,292 adults seen at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP) in 1988–93.7 This study documented the substantial toll of HIV infection, which was the leading cause of death among 25–44 year olds and accounted for 18% of all deaths in the study cohort. Homicide was the principal cause of death for 18–24 year olds, while heart disease and cancer were the leading causes among 45–64 year olds.

In view of interim advances in HIV treatment and expansion of federally-funded Health Care for the Homeless clinical services, the mortality profile of homeless adults in the U.S. may have changed since 1988–93; however, data to confirm this are lacking. A comprehensive reassessment of mortality and causes of death among homeless adults would provide a needed update on the health status of this vulnerable population and inform policy decisions and clinical practice priorities regarding the provision of health care and other services for this group of people.

Using methods similar to the 1988–93 Boston mortality study,7 we assessed overall and cause-specific mortality rates in a large cohort of adults who used services provided by BHCHP in 2003–08. We compared these mortality rates to the general population of Massachusetts residents in 2003–08 and to the cohort of homeless adults seen by BHCHP in 1988–93. We also examined racial variations in mortality since prior studies of homeless individuals have found paradoxically higher death rates among whites than non-whites.6, 12, 18

METHODS

Participants and setting

We retrospectively assembled a cohort of all adults aged ≥18 years who had an in-person encounter at BHCHP between January 1, 2003, and December 31, 2008. BHCHP serves more than 11,000 individuals annually in over 90,000 outpatient medical, oral health, and behavioral health encounters through a network of over 80 service sites based in emergency shelters, transitional housing facilities, hospitals, and other social service settings in greater Boston.19, 20 Patients must be homeless to enroll in services at BHCHP; no other eligibility requirements are imposed. Some patients elect to continue receiving care at BHCHP after they are no longer homeless. Due to limitations in the data, we were unable to distinguish currently versus formerly homeless participants, so this study represents an analysis of adults who have ever experienced homelessness. We refer to this group as “homeless” for simplicity. Individuals were observed from the date of first contact within the study period until the date of death or December 31, 2008. We measured observation time in person-years. The Partners Human Research Committee approved this study.

Ascertainment of vital status

We used LinkPlus version 2.0 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Atlanta, GA) to cross-link the BHCHP cohort with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) death occurrence files for 2003–08. LinkPlus is a probabilistic record linkage software program that uses expectation maximization algorithms and an array of linkage tools to compute linkage probability scores for possible record pairs based on the level of agreement and relative importance of various personal identifiers.21 Our primary linkage procedure utilized first and last name, date of birth, and social security number (SSN); sensitivity analyses utilized sex and race with no additional linkages identified. There were minimal missing data for the core identifiers in the BHCHP cohort (0% for name and birth date, 9% for SSN). We manually reviewed record pairs achieving a probability score of 7 or higher21 and generally accepted a record pair as a true linkage if it matched on one of the following National Death Index criteria22 that were also used in the 1988–93 BHCHP mortality study7: 1) SSN, 2) first and last name, month and year of birth (+/− 1 year), or 3) first and last name, month and day of birth. Two investigators independently conducted the manual review with very high concordance and inter-rater reliability (Kappa=0.99). A third investigator adjudicated discrepancies.

Causes of death

We based causes of death on the International Classification of Diseases – 10th Edition (ICD-10) underlying cause of death codes in the MDPH mortality file (eTable). The MDPH translates death certificate entries into ICD-10 cause of death codes using software developed by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).23 We defined “drug overdose” as drug poisoning deaths that were unintentional (X40–X44) or of undetermined intent (Y10–Y14).24 We included undetermined intent drug poisonings in this definition because Massachusetts medical examiners made relatively frequent use of this category prior to a 2005 policy change at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner requiring most of these deaths to be categorized as unintentional.23, 25 Additionally, evidence suggests that poisonings of undetermined intent more closely resemble unintentional poisonings than suicidal poisonings.26 For drug overdose deaths, we examined the multiple cause of death fields to ascertain which substances were implicated in each overdose. We classified deaths due to alcohol poisoning (X45, Y15) separately from drug overdose. Drug-and alcohol-related deaths could also be captured under the ICD-10 underlying cause of death codes for mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10–F19), which we analyzed collectively as “psychoactive substance use disorders.” These codes are generally intended for deaths related to a chronic pattern or sequel of substance abuse rather than acute poisoning.27 Such deaths include those attributed to substance dependence (e.g. chronic alcoholism), harmful substance use resulting in medical complications (e.g. dilated cardiomyopathy, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, aspiration pneumonia), and substance withdrawal syndromes (e.g. delirium tremens) (Robert N. Anderson, PhD, Chief, Mortality Statistics Branch, NCHS, written communication, June 22, 2012).

Statistical analyses

We tabulated the leading causes of death overall and stratified by age and sex. We calculated mortality rates by dividing the number of deaths by the person-years of observation and expressed these rates as deaths per 100,000 person-years. Since the accuracy of the underlying cause of death may depend upon whether a decedent underwent autopsy, we assessed the percentage of homeless decedents who underwent autopsy and used the Chi-square test to compare this to the percentage that underwent autopsy in the Massachusetts general population.

To compare our age- and sex-stratified findings to the 2003–08 Massachusetts general population, we adjusted for race using direct standardization with weights chosen according to the racial breakdown in the general population. We then calculated overall and cause-specific mortality rate ratios by dividing the race-standardized mortality rates in the homeless cohort by the rates in the general population. We fit 95% confidence intervals using conventional methods for standardized rate ratios.28, 29 We obtained Massachusetts mortality data from the CDC Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) underlying cause of death compressed mortality files for 2003–08.30

To compare our findings to the 1988–93 BHCHP cohort, we directly standardized the overall and cause-specific mortality rates in the 2003–08 cohort to match the age, sex, and race distribution of the 1988–93 cohort. We limited this portion of the analysis to 18–64 year olds to correspond to the age range analyzed in 1988–93. Between 1988 and 2008, BHCHP experienced substantial growth in the density and intensity of its clinical operations but did not change its core mission, geographical service area, target population, or eligibility requirements for patient enrollment.20 To gauge the potential impact of this clinical expansion, we distinguished between natural and external causes of death (eTable),27 because the former may be more responsive to traditional medical interventions. Since causes of death were classified according to ICD-9 codes in 1988–93 and ICD-10 codes in 2003–08, we applied comparability ratios (CR; eTable) using methods outlined by the NCHS.31–33 We used the CR for drug-induced deaths to analyze drug overdose mortality. We used the CR for alcohol-induced deaths to analyze mortality due to psychoactive substance use disorders since the majority of these deaths were alcohol-related.

To assess for racial differences in mortality, we compared the age-standardized all-cause mortality rates for white, black, and Hispanic adults, stratified by sex. We used SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) to conduct our analyses.

RESULTS

A total of 28,033 adults were followed for a median of 3.3 years, yielding 90,450 person-years of observation. The mean age at cohort entry was 41 years (Table 1). In comparison to 1988–93, individuals 45 years and older comprised a greater proportion of observation time (45% vs. 29%). Two-thirds of participants were male and 42.5% were white.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the entire study cohort (N=28,033) and the decedents (N=1,302).

| Entire cohort | N=28,033 |

| Age at index observation | |

| Mean (SD) | 41.0 (12.4) |

| 18–24 years, N(%) | 3,493 (12.5) |

| 25–44 years, N (%) | 13,805 (49.3) |

| 45–64 years, N (%) | 9,924 (35.4) |

| 65–84 years, N (%) | 793 (2.8) |

| ≥85 years, N (%) | 18 (0.1) |

| Sex | |

| Male, N (%) | 18,612 (66.4) |

| Female, N (%) | 9,421 (33.6) |

| Race | |

| White, non-Hispanic, N (%) | 11,912 (42.5) |

| Black, non-Hispanic, N (%) | 8,066 (28.8) |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 5,301 (18.9) |

| Other/unknown, N (%) | 2,754 (9.8) |

| Decedents | N=1,302 |

| Age at death, mean (range) | 51.2 (19.3–93.5) |

| Sex | |

| Male, N (%) | 1,055 (81.0) |

| Female, N (%) | 247 (19.0) |

| Race | |

| White, non-Hispanic, N (%) | 784 (60.2) |

| Black, non-Hispanic, N (%) | 301 (23.1) |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 131 (10.1) |

| Other/unknown, N (%) | 86 (6.6) |

| Veteran, N (%) | 164 (12.6) |

| Place of death | |

| Hospital, N (%) | 683 (52.5) |

| Residence, N (%) | 352 (27.0) |

| Nursing Home, N (%) | 129 (9.9) |

| Other, N (%) | 138 (10.6) |

| Autopsy performed | |

| Yes, N (%) | 495 (38.0) |

| No, N (%) | 807 (62.0) |

There were 1,302 deaths during the study period, generating a crude mortality rate of 1,439.5 deaths per 100,000 person-years. The mean age at death was 51 years (range 19–93) (Table 1). Over 80% of decedents were male and 60.2% were white. The majority of deaths occurred in a hospital. Overall, 38.0% of decedents in the study cohort underwent autopsy as compared to 6.7% of decedents in the Massachusetts general population (p<0.001).

Causes of death

Drug overdose was the leading cause of death, accounting for 16.8% of all deaths in the cohort (Table 2). Opioids were implicated in 81% of overdose deaths; of these, heroin was identified in 13%, opioid analgesics in 31%, and other and unspecified narcotics in 60%. Cocaine contributed to 37% of overdose deaths, and 43% involved multiple substances. Alcohol was mentioned as a co-occurring substance in 32% of drug overdose deaths.

Table 2.

Causes of death and crude mortality rates.

| Underlying cause of deatha | Number of deaths (% of total) | Crude rate per 100,000 person-years (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| All causes | 1302 (100.0) | 1439.5 (1361.3 – 1517.7) |

| Drug overdose | 219 (16.8) | 242.1 (210.1 – 274.2) |

| Cancer | 206 (15.8) | 227.8 (196.6 – 258.9) |

| Trachea, bronchus, and lung | 74 (5.7) | 81.8 (63.2 – 100.5) |

| Liver and intrahepatic bile ducts | 24 (1.8) | 26.5 (15.9 – 37.1) |

| Colon, rectum, and anus | 18 (1.4) | 19.9 (10.7 – 29.1) |

| Esophagus | 11 (0.8) | 12.2 (5.0 – 19.3) |

| Pancreas | 8 (0.6) | 8.8 (2.7 – 15.0) |

| Heart disease | 203 (15.6) | 224.4 (193.6 – 255.3) |

| Psychoactive substance use disorder | 99 (7.6) | 109.5 (87.9 – 131.0) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 71 (5.5) | 78.5 (60.2 – 96.8) |

| Other substance use disorders | 28 (2.2) | 31.0 (19.5 – 42.4) |

| Liver disease | 89 (6.8) | 98.4 (78.0 – 118.8) |

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 58 (4.5) | 64.1 (47.6 – 80.6) |

| Other liver diseases | 31 (2.4) | 34.3 (22.2 – 46.3) |

| HIV disease | 76 (5.8) | 84.0 (65.1 – 102.9) |

| Ill-defined conditions | 41 (3.1) | 45.3 (31.5 – 59.2) |

| Suicide | 36 (2.8) | 39.8 (26.8 – 52.8) |

| Transport accident | 26 (2.0) | 28.7 (17.7 – 39.8) |

| Pedestrian injured in transport accident | 15 (1.2) | 16.6 (8.2 – 25.0) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 25 (1.9) | 27.6 (16.8 – 38.5) |

| Diabetes | 24 (1.8) | 26.5 (15.9 – 37.1) |

| Other accidents | 23 (1.8) | 25.4 (15.0 – 35.8) |

| Sepsis | 22 (1.7) | 24.3 (14.2 – 34.5) |

| Homicide | 21 (1.6) | 23.2 (13.3 – 33.1) |

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis | 21 (1.6) | 23.2 (13.3 – 33.1) |

| Events of undetermined intent | 21 (1.6) | 23.2 (13.3 – 33.1) |

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 20 (1.5) | 22.1 (12.4 – 31.8) |

| Viral hepatitis | 18 (1.4) | 19.9 (10.7 – 29.1) |

| Anoxic brain injury | 12 (0.9) | 13.3 (5.8 – 20.8) |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 11 (0.8) | 12.2 (5.0 – 19.3) |

| Metabolic disorders | 8 (0.6) | 8.8 (3.8 – 17.4) |

| Alcohol poisoning | 6 (0.5) | 6.6 (2.4 – 14.4) |

| All other causes | 75 (5.8) | 82.9 (64.2 – 101.7) |

Causes of death are based on the International Classification of Diseases – 10th Revision (ICD-10). See the eTable for the ICD-10 codes used to define each cause of death.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval

Cancer and heart disease were also major causes of death, each accounting for about 16% of deaths (Table 2). Malignant neoplasms of the trachea, bronchus, and lung comprised over one-third of all cancer deaths. Psychoactive substance use disorders caused nearly 8% of all deaths, and 72% of these were attributable to alcohol.

Mortality rate ratios by age and sex

Drug overdose was the leading cause of death among 25–44 year old homeless men and women, accounting for 35% of deaths at rates 16- to 24-fold higher than those in the Massachusetts general population (Table 3). All-cause mortality rates for men and women in this age group were 8.6- and 9.6-fold higher than in the general population.

Table 3.

Leading causes of death and race-adjusted mortality rate ratios by age group and sex.

| 25–44 years | 45–64 years | 65–84 years | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Cause | N | Crude Ratea | Race-adjusted Rate Ratiob (95% CI) | Cause | N | Crude Ratea | Race-adjusted Rate Ratiob (95% CI) | Cause | N | Crude Ratea | Race-adjusted Rate Ratiob (95% CI) |

| Men | |||||||||||

| 1) Drug overdose | 92 | 346.9 | 16.0 (12.6, 20.3) | 1) Cancer | 120 | 418.7 | 2.2 (1.8, 2.8) | 1) Cancer | 38 | 1350.4 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) |

| 2) Heart disease | 24 | 90.5 | 5.1 (3.1, 8.4) | 2) Heart disease | 114 | 397.8 | 3.5 (2.8, 4.3) | 2) Heart disease | 36 | 1279.3 | 1.4 (0.9, 2.1) |

| 3) Psychoactive substance use disorder | 24 | 90.5 | 22.1 (14.0, 34.9) | 3) Drug overdose | 80 | 279.1 | 17.5 (13.6, 22.5) | 3) Chronic lower respiratory disease | 5 | 177.7 | 0.9 (0.3, 2.5) |

| 4) HIV | 21 | 79.2 | 17.3 (10.1, 29.8) | 4) Psychoactive substance use disorder | 59 | 205.9 | 19.6 (14.6, 26.4) | 4) Cerebrovascular disease | 4 | 142.1 | 0.7 (0.2, 2.5) |

| 5) Suicide | 15 | 56.6 | 7.1 (4.2, 11.8) | 5) Liver disease | 58 | 202.4 | 7.7 (5.7, 10.3) | 5) Sepsis | 4 | 142.1 | 1.1 (0.3, 5.0) |

| All causes | 252 | 950.1 | 8.6 (7.4, 9.9) | All causes | 670 | 2337.7 | 4.5 (4.1, 4.9) | All causes | 114 | 4051.3 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Women | |||||||||||

| 1) Drug overdose | 28 | 172.6 | 23.6 (15.2, 36.6) | 1) Cancer | 28 | 326.4 | 1.9 (1.1, 3.1) | 1) Cancer | 6 | 672.4 | 1.3 (0.5, 3.0) |

| 2) Heart disease | 8 | 49.3 | 3.6 (1.2, 11.1) | 2) Heart disease | 16 | 186.5 | 3.0 (1.5, 6.1) | 2) Heart disease | 4 | 448.3 | 1.1 (0.4, 3.2) |

| 3) HIV | 7 | 43.1 | 9.7 (2.9, 32.4) | 3) Drug overdose | 14 | 163.2 | 21.2 (11.4, 39.5) | 3) Diabetes | 3 | 336.2 | 5.8 (1.5, 22.1) |

| 4) Psychoactive substance use disorder | 7 | 43.1 | 33.0 (13.0, 83.7) | 4) Liver disease | 12 | 139.9 | 16.9 (9.2, 30.9) | ||||

| 5) Liver disease | 6 | 37.0 | 21.3 (8.4, 53.9) | 5) HIV | 8 | 93.3 | 18.0 (6.1, 52.5) | ||||

| All causes | 95 | 585.6 | 9.6 (7.4, 12.4) | All causes | 126 | 1469.0 | 4.5 (3.6, 5.6) | All causes | 21 | 2353.4 | 1.1 (0.7, 1.8) |

Deaths per 100,000 person-years of observation.

Mortality rate ratios were calculated by dividing the race-adjusted mortality rates for the homeless cohort by the corresponding mortality rates in the general population of Massachusetts during the same years (2003–08). Race adjustment was performed using direct standardization to match the racial and ethnic breakdown of the specified age and sex groups within the general population of Massachusetts.

Cancer and heart disease were the leading causes of death among 45–64 year old homeless adults, and the mortality rates for these causes were about 2- and 3-fold higher than in the general population. All-cause mortality rates in this age group were 4.5-fold higher than in the general population. Among 65–84 year olds, overall and cause-specific mortality rates generally were not significantly different than in comparably aged adults in Massachusetts.

Comparison to 1988–93 cohort

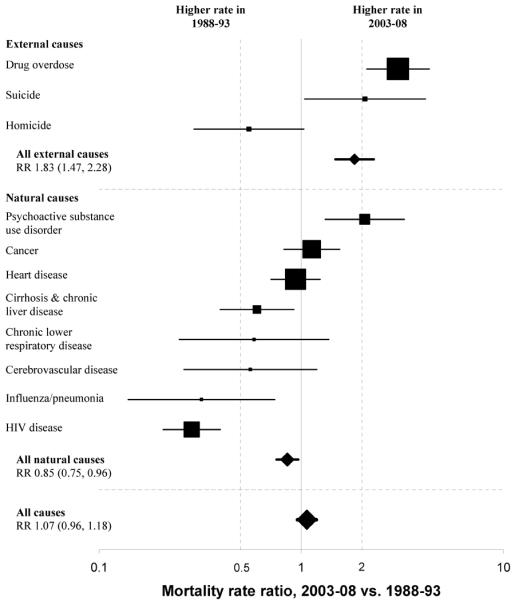

The age-, sex-, and race-standardized mortality rate among 18–64 year old adults in the current study was not significantly different than in the 1988–93 BHCHP cohort (Figure 1). However, there were significant differences with respect to specific causes of death. A 3-fold increase in drug overdose deaths and a 2-fold increase in suicide deaths contributed to an 83% higher rate of deaths due to external causes in comparison to 1988–93. Despite a 2-fold increase in deaths due to psychoactive substance use disorders, significant reductions in deaths due to HIV and cirrhosis contributed to a 15% overall decrease in natural causes of death.

Figure 1.

Mortality rate ratios comparing cause-specific and overall mortality rates for the 2003–08 and 1988–93 homeless cohorts.

Note: Boxes are weighted in proportion to the total number of deaths due to the specified cause. Prior to computing rate ratios, mortality rates from the 2003–08 cohort were directly standardized to the age, sex, and race distribution of the 1988–93 cohort. Differences between ICD-9 (1988–93) and ICD-10 (2003–08) underlying cause of death codes were accounted for using comparability ratios from the National Center for Health Statistics. See eTable for ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes and comparability ratios.

Abbreviations: RR, rate ratio

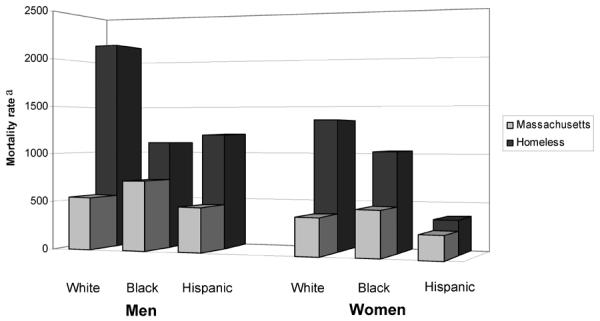

Racial variations in mortality

White men had a significantly higher age-standardized mortality rate than black men (rate ratio [RR], 1.94; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.66–2.28) and Hispanic men (RR 1.80; 95% CI 1.47–2.21). The age-standardized mortality rate in white women was substantially higher than in Hispanic women (RR 3.81; 95% CI 2.19–6.61) and marginally higher than in black women (RR 1.31; 95% CI 0.99–1.74). Figure 2 juxtaposes these rates with those expected in the Massachusetts general population if it had the same age distribution as the homeless cohort.

Figure 2.

Race-specific age-standardized mortality rates for homeless adults and adults in the general population of Massachusetts (2003–08), stratified by sex.b

aMortality rate expressed as the number of deaths per 100,000 person-years of observation for the homeless cohort, and deaths per 100,000 for the Massachusetts general population.

bAll mortality rates are directly standardized to match the age distribution of the homeless cohort using the following categories: 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and ≥65 years. Due to limitations in state data, the age-specific mortality rate for 20–24 year old Massachusetts adults was used to estimate the rate for 18–24 year old adults.

COMMENT

Drug overdose was the leading cause of death in this cohort of currently and formerly homeless adults, occurring at substantially higher rates than in the Massachusetts general population. Despite comprising only 0.3% of the state's adult population, the study cohort accounted for 5% of all drug overdose deaths among Massachusetts adults in 2003–08. Opioids contributed to over 80% of these deaths. Cancer and heart disease were the leading causes of death among adults 45 years and older. In comparison to the general population, the greatest disparities in all-cause mortality occurred in the younger age groups.

There was no significant difference between the all-cause mortality rate in 2003–08 as compared to 1988–93. A 15% reduction in deaths due to natural causes was offset by an 83% increase in deaths due to external causes. Although HIV-related deaths decreased considerably, we found a 3-fold increase in drug overdose deaths and 2-fold increases in deaths due to suicide and psychoactive substance use disorders.

Similar to prior studies,6, 12, 18 we found significantly higher mortality rates among white homeless adults in comparison to other racial groups, which differs from the pattern in the general population. This may reflect underlying racial differences in the pathways to homelessness. Evidence suggests that African-Americans are more likely to be homeless because of structural factors such as discrimination and poverty, while homelessness among whites is more heavily linked to personal factors such as mental illness, trauma, family dysfunction, and substance abuse,34–36 placing these individuals at higher risk of death. This is supported by the finding that whites accounted for a particularly disproportionate percentage of deaths due to drug overdose (68%), substance use disorders (68%), and suicide (89%).

Our findings have implications for policymakers, public health professionals, and clinicians serving this population. The overall mortality pattern of homeless adults in this study demonstrates the substantial impact of substance abuse and mental illness, highlighting the need for integrated systems of care to address these complex issues. Interval increases in deaths due to drug overdose, psychoactive substance use disorders, and suicide suggest that chemical dependency counselors, psychiatrists, and other behavioral health specialists should be collocated with primary care practitioners serving this population. The dramatic rise in drug overdose deaths reflects a broader nationwide trend in drug poisoning mortality fueled largely by rising opioid-related deaths.37–39 Such deaths are fundamentally preventable. The bulk of opioid overdoses were due to non-heroin substances, including opioid analgesics and other narcotics. Given the high prevalence of both chronic pain and addiction in homeless persons,40 health care organizations serving this population may wish to develop standardized pain management protocols to help ensure safe, effective, and appropriate opioid prescribing. Efforts to curb prescription drug diversion should remain a national policy priority. Public health initiatives aiming to prevent and reverse opioid overdoses through education and the distribution of intranasal naloxone may also help reduce these deaths.41, 42 In addition to methadone maintenance programs, office-based buprenorphine treatment appears to be feasible in the setting of homelessness43 and may be an effective option for addressing opioid dependence in this population.

The impact of alcohol and tobacco use is also apparent. Alcohol was the principal substance implicated in 72% of deaths due to psychoactive substance use disorders and was a co-occurring substance in one-third of drug overdose deaths. The preponderance of deaths due to heart disease and cancer, particularly neoplasms of the trachea, bronchus, and lung, suggests a pressing need to address the 73% prevalence of cigarette smoking among homeless adults.44 The heavy burden of such deaths among the growing subset of individuals 45 years and older reinforces the need for primary care and preventive services that target the health issues of an aging homeless population.45

Between 1988 and 2008, BHCHP substantially expanded the scope of its clinical services in greater Boston.20 While causality cannot be determined, this expansion may partially explain the interim reduction in natural causes of death that may be more amenable to medical interventions than external causes. However, the lack of change in all-cause mortality is consistent with the fact that multiple factors other than health care influence population health.46 Addressing the substantial mortality disparities in homeless populations will require not only clinical innovation and tailored health care services, but also creative public health programming combined with policy initiatives to address homelessness and other social determinants of health.

Limitations

We studied adults who used Health Care for the Homeless clinical services in Boston. Our findings may not be generalizable to homeless individuals who avoid such services or to homeless adults in other cities. Our study included both currently and formerly homeless adults, which likely exerts a conservative bias on our findings since individuals who have exited homelessness may have lower mortality rates.18 Finally, the accuracy of death certificates in identifying cause of death has been debated.47 Death certificates have poor sensitivity but high specificity for identifying drug poisoning deaths,48 implying a low likelihood for “false positive” drug overdose deaths in our study. Death certificates also appear relatively accurate in identifying cancer deaths,49, 50 the second most common cause of death in this study. Furthermore, decedents in this study underwent autopsy at a 6-fold higher rate than decedents in the Massachusetts general population, providing some reassurance that the cause of death information is not less accurate, and may be more accurate, than for non-homeless individuals.

Conclusions

Drug overdose has replaced HIV as the emerging epidemic among homeless adults. While mortality rates due to certain causes have decreased in comparison to 15 years prior, we found substantial increases in addiction-related and mental health-related mortality rates among homeless adults, resulting in no overall change in mortality despite a major expansion in clinical services for this population. Findings suggest the need to integrate psychiatric and substance abuse services into primary medical care and to expand public health efforts to curb the growing problem of opioid-related deaths. The mortality disparity between homeless individuals and the general population, particularly among those who are youngest, underscores the need to address the social determinants of health through policy initiatives to eradicate homelessness.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding/Support and Role of Sponsor Funding for this study was provided by the General Medicine Division at Massachusetts General Hospital and by Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Baggett also receives funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23DA034008. The study content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. These funding entities had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Travis Baggett and James O'Connell are staff physicians at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, where they receive financial compensation for rendering patient care services. At the time of the study, Erin Stringfellow was employed by Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program as a research coordinator.

Other Contributions We thank Kevin Foster, MPH, at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health's Registry of Vital Statistics for his assistance in accessing the state's death occurrence files. We thank Robert N. Anderson, PhD, Chief of the Mortality Statistics Branch at the National Center for Health Statistics, for his assistance in explaining certain cause of death codes. We thank Jill Roncarati, PA, MPH, for her clinical and analytic insight in interpreting the study findings. We thank Leah Isquith, BA, and Julie Marston, MPH, in the Research Department at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program for their support and assistance in conducting this study. These individuals did not receive financial compensation for their contributions. This manuscript does not represent the views or work of these individuals or their respective agencies.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: A preliminary summary of a portion of the study findings was presented on May 6, 2011, at the 34th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in Phoenix, Arizona. An updated summary of the study findings was presented on May 16, 2012, at the National Health Care for the Homeless Council Annual Conference and Policy Symposium in Kansas City, Missouri.

Conflicts of Interest and Financial Disclosures We have no other potential conflicts of interest to report.

Data Access and Responsibility Travis Baggett had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burt MR, Aron LY, Lee E, Valente J. Helping America's Homeless: Emergency Shelter or Affordable Housing? Urban Institute; Washington, D.C.: 2001. How Many Homeless People Are There? pp. 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Office of Community Planning and Development [Accessed February 29, 2012];The 2010 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. 2011 http://www.hudhre.info/documents/2010HomelessAssessmentReport.pdf.

- 3.Burt MR, Urban Institute . Homelessness: Programs and the People They Serve: Findings of the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients: Technical Report. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; Office of Policy Development and Research; Washington, D.C.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breakey WR, Fischer PJ, Kramer M, et al. Health and mental health problems of homeless men and women in Baltimore. JAMA. 1989 Sep 8;262(10):1352–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright JD. The Health of Homeless People: Evidence from the National Health Care for the Homeless Program. In: Brickner PW, Scharer LK, Conanan B, Savarese M, Scanlan BC, editors. Under the Safety Net: The Health and Social Welfare of the Homeless in the United States. Norton; New York: 1990. pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hibbs JR, Benner L, Klugman L, et al. Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia. N Engl J Med. 1994 Aug 4;331(5):304–309. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O'Connell JJ, Lebow JM, Brennan TA. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Apr 15;126(8):625–628. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrow SM, Herman DB, Cordova P, Struening EL. Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1999 Apr;89(4):529–534. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. JAMA. 2000 Apr 26;283(16):2152–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.16.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung AM, Hwang SW. Risk of death among homeless women: a cohort study and review of the literature. CMAJ. 2004 Apr 13;170(8):1243–1247. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, O'Campo PJ, Dunn JR. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck R. Mortality among homeless and nonhomeless mentally ill veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000 Mar;188(3):141–147. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordentoft M, Wandall-Holm N. 10 year follow up study of mortality among users of hostels for homeless people in Copenhagen. BMJ. 2003 Jul 12;327(7406):81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7406.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen SF, Hjorthoj CR, Erlangsen A, Nordentoft M. Psychiatric disorders and mortality among people in homeless shelters in Denmark: a nationwide register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2011 Jun 25;377(9784):2205–2214. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60747-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison DS. Homelessness as an independent risk factor for mortality: results from a retrospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2009 Jun;38(3):877–883. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Sochanski B, Boudreau JF, Boivin JF. Mortality in a cohort of street youth in Montreal. JAMA. 2004 Aug 4;292(5):569–574. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beijer U, Andreasson S, Agren G, Fugelstad A. Mortality and causes of death among homeless women and men in Stockholm. Scand J Public Health. 2011 Mar;39(2):121–127. doi: 10.1177/1403494810393554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metraux S, Eng N, Bainbridge J, Culhane DP. The impact of shelter use and housing placement on mortality hazard for unaccompanied adults and adults in family households entering New York City shelters: 1990–2002. J Urban Health. 2011 Dec;88(6):1091–1104. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9602-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program [Accessed February 29, 2012];2010 www.bhchp.org.

- 20.O'Connell JJ, Oppenheimer SC, Judge CM, et al. The Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program: a public health framework. Am J Public Health. 2010 Aug;100(8):1400–1408. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.173609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Registry Plus: Link Plus Users Guide. Version 2.0 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Cancer Division; Atlanta, GA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Center for Health Statistics [Accessed February 29, 2012];National Death Index Matching Criteria. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi.htm.

- 23.West J, Hood M, Caceres I, Cohen B. Massachusetts Deaths, 2008. Massachusetts Department of Public Health; Division of Research and Epidemiology; Bureau of Health Information; Statistics, Research, and Evaluation; Boston, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Desai HA. Prescription drug monitoring programs and death rates from drug overdose. Pain Med. 2011 May;12(5):747–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breiding MJ, Wiersema B. Variability of undetermined manner of death classification in the US. Inj Prev. 2006 Dec;12(Suppl 2):ii49–ii54. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.012591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donaldson AE, Larsen GY, Fullerton-Gleason L, Olson LM. Classifying undetermined poisoning deaths. Inj Prev. 2006 Oct;12(5):338–343. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.011171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson RN, Minino AM, Fingerhut LA, Warner M, Heinen MA. Deaths: injuries, 2001. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2004 Jun 2;52(21):1–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman SC. Biostatistical Methods in Epidemiology. Wiley; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics Compressed Mortality File 1999–2008. [Accessed April 19, 2012];CDC WONDER Online Database, compiled from Compressed Mortality File 1999–2008 Series 20 No. 2N. 2011 http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html.

- 31.Kochanek K, Smith B, Anderson RN. National vital statistics reports. no 3. vol 49. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, Maryland: 2001. Deaths: Preliminary data for 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson RN, Minino AM, Hoyert DL, Rosenberg HM. Comparability of cause of death between ICD-9 and ICD-10: preliminary estimates. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001 May 18;49(2):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minino AM, Parsons VL, Maurer JD, et al. Part II: Applying Comparability Ratios. National Center for Health Statistics; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000. A Guide to State Implementation of ICD-10 for Mortality. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed SR, Toro PA. African-Americans. In: Levinson D, editor. Encyclopedia of Homelessness. Vol 1. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 2004. pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.North CS, Smith EM. Comparison of white and nonwhite homeless men and women. Soc Work. 1994 Nov;39(6):639–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenheck R, Bassuk EL, Salomon A. Special Populations of Homeless Americans. Paper presented at: National Symposium on Homelessness Research: What Works?; Arlington, VA. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warner M, Chen L, Makuc D, Anderson RN, Minino AM. NCHS Data Brief, No. 81. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2011. Drug Poisoning Deaths in the United States, 1980–2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006 Sep;15(9):618–627. doi: 10.1002/pds.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulozzi LJ, Xi Y. Recent changes in drug poisoning mortality in the United States by urban-rural status and by drug type. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008 Oct;17(10):997–1005. doi: 10.1002/pds.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hwang SW, Wilkins E, Chambers C, Estrabillo E, Berends J, MacDonald A. Chronic pain among homeless persons: characteristics, treatment, and barriers to management. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone - United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Feb 17;61:101–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. [Accessed March 5, 2012];Patrick-Murray Administration Announces New Milestone in Fight Against Opiate Overdose Deaths in Massachusetts: 1000th opiate overdose reversal due to innovative Narcan pilot program. 2011 http://www.mass.gov/governor/administration/ltgov/lgcommittee/subabuseprevent/new-milestone-in-fighting-opiate-overdose-deaths.html.

- 43.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Feb;22(2):171–176. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baggett TP, Rigotti NA. Cigarette smoking and advice to quit in a national sample of homeless adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010 Aug;39(2):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.024. DOI: 110.1016/j.amepre.2010.1003.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hahn JA, Kushel MB, Bangsberg DR, Riley E, Moss AR. BRIEF REPORT: the aging of the homeless population: fourteen-year trends in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Jul;21(7):775–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005 Mar 19–25;365(9464):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ravakhah K. Death certificates are not reliable: revivification of the autopsy. South Med J. 2006 Jul;99(7):728–733. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000224337.77074.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moyer LA, Boyle CA, Pollock DA. Validity of death certificates for injury-related causes of death. Am J Epidemiol. 1989 Nov;130(5):1024–1032. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kircher T, Nelson J, Burdo H. The autopsy as a measure of accuracy of the death certificate. N Engl J Med. 1985 Nov 14;313(20):1263–1269. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511143132005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.German RR, Fink AK, Heron M, et al. The accuracy of cancer mortality statistics based on death certificates in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010 Apr;35(2):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.