Abstract

Universally, anesthesiologists are expected to be knowledgeable, astutely responding to clinical challenges while maintaining a prolonged vigilance for administration of safe anesthesia and critical care. A fatigued anesthesiologist is the consequence of cumulative acuity, manifesting as decreased motor and cognitive powers. This results in impaired judgement, late and inadequate responses to clinical changes, poor communication and inadequate record keeping. With rising expectations and increased medico-legal claims, anesthesiologists work round the clock to provide efficient and timely services, but are the "sleep provider" in a sleep debt them self? Is it the right time to promptly address these issues so that we prevent silent perpetuation of problems pertinent to anesthesiologist’s health and the profession. The implications of sleep debt on patient safety are profound and preventive strategies are quintessential. Anesthesiology governing bodies must ensure requisite laws to prevent the adverse outcomes of sleep debt before patient care is compromised.

Keywords: Anaesthesiologist, sleep, fatigue, sleep deprivation, patient safety

Introduction

Fatigue is a ubiquitous fact of our professional lives. Anesthesiology allows a very small margin of error with a short-time interval to comprehend and rectify the mistake. An effective patient care by an anesthesiologist demands assemblage and iteration of data, correlated to patient condition, planning and executing strategies, and intense monitoring for a favorable patient outcome. Each of these highly stressful, energy soaking responsibilities demand a sustained, extraordinary levels of vigilance. The practice of “eternal vigilance” has its price.[1–3] Strenuous mental and physical stress leads to fatigue and sleep deficit. Fatigue in anesthesiologists is accepted as norm or mostly ignored. We believe that because fatigue is understudied it possess a potent hazard for patient safety. This review dwells on the physiology of fatigue and pathology caused due to it, factors affecting it, and a few suggestions to avoid and manage fatigue.

Physiology of fatigue

Fatigue is defined as a temporary loss of strength and energy resulting from hard physical or mental work; usually associated with performance decrement.[4] This results when the body cannot provide enough energy to perform a task. The depletion of energy stores result in muscle fatigue to the point where physical or mental activity cannot be performed. Three types of fatigue have been described as:[5]

Transient - brought on by extreme sleep restriction or extended hours awake (1-2 days).

Cumulative - repeated mild sleep restriction or extended hours awake across a series of days.

Circadian - the reduced performance during nighttime hours, particularly during an individual’s window of circadian low (WOCL) (typically between 2 am and 6 am).

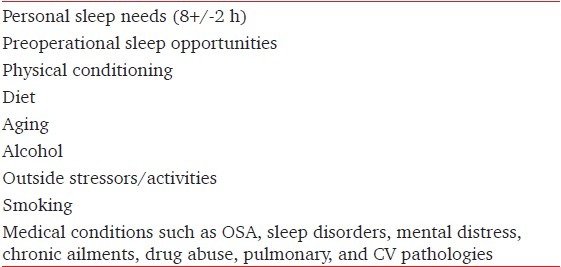

When fatigue reaches a point where activity cannot be resumed even after a period of rest, exhaustion ensues. Realistically, a fatigued anesthesiologist (like an aviator) is prone to compromise monitoring of the patients, which may lead to wrong interpretation of parameter and thereby resulting in erroneous decisions.[1,4] There are various factors that contribute to the onset of fatigue [Table 1].

Table 1.

Etiology of fatigue

Disruption of circadian dynamics

In the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus,[6] humans have a circadian center that regulates many body processes such as temperature and hormone secretion. The daily light/dark variation via retino-hypothalamic pathway entrains this clock to the 24-h day. Humans are programmed for two periods of least vigilance between 3-7 am and 1-4 pm every day and the maximal alertness is approximately during 9-11 am and 9-11 pm. The lowest point in this cycle occurs during the early morning, making it the period of greatest vulnerability to fatigue-related performance impairment[7] supported by the fact that maximum incidence of fatigue-related single car accidents, even without alcohol involvement, occurs roughly between 3 and 5 am.[8,9]

The circadian pacemaker is resistant to change after a night shift work and/or trans-meridian air travel. This is the primary reason for the inability of humans to readily adapt to shift work and the reason for jet lag. For example, workers on night shift attempt to function when their clocks are primed for sleep. When they attempt to sleep during the day, their body-clock is programmed for wakefulness. Opposing this, normal rhythmic pattern of day-awake and night-asleep is made more difficult because societal activities are strongly linked to this pattern. Some errands and family responsibilities can only be performed during the day, making adaptation to shift work difficult. Aya correlated increased risk of unintentional dural puncture during epidural anesthesia at night (midnight to 8 am), which suggests performance decrement among anesthesiologists maybe induced by circadian rhythm alteration.[10]

Alteration of normal sleep homeostasis

Individually, we possess a genetically hard-wired sleep requisite. Sleep is a physiologic drive analogous to hunger or thirst.[11] Surveys done by the National Sleep Foundation reveal that we are a society of chronic under sleepers, by more than an hour per night. When basic sleep requirements of about 8 h[12] per day (~6 to10 h) are not met a “sleep debt” ensues and sleepiness manifests.[13] The only way to pay off this “sleep debt” is by adequate sleep. Research has shown that sleeping 6 h or less per night over 2 weeks results in cognitive performance deficits equivalent to two nights of total sleep deprivation.[14] Kripke studied chronic partial sleep deprivation and offers imperative evidence to practicing physicians.[15]

It has been shown that when subjective somnolence was assessed, subjects were essentially oblivious of their level of impairment. Most of us assume chronic sleep deprivation to be a benign state of health. Sleep deficit is compounded by age.[16] Normal aging affects sleep, making it light, erratic, and disruptive. Consequently, elders experience more daytime somnolence.

Microsleeps[17] are brief involuntary, episodes of physiological sleep, which may last a fraction of second or up to 30 s and can occur at any time, typically without warning. It usually manifests as head nods, drooping eyelids, etc., It is hazardous in acute patient care and has caused catastrophes.[17] Sleep debt after sleep deprivation manifests as somnolence. Wakefulness exceeding 16 h predicts performance lapses.[18] Extending work shifts past 17 consecutive hours increases the likelihood of errors in clinical settings and laboratory.[19] The physiologic pressure for sound sleep increases with accumulative hours since the last sleep episode. The way to get over the debt is to invest in sound sleep (daytime naps); unfortunately very few professionals enjoy the luxury of catnaps.

Using ambulatory EEG and videotaping clinicians to quantify sleep, Lockley[20] revealed increased incidence of “Attentional failures” in interns working 30-h duty periods when compared to shorter work shifts. Howard[21] reproduced similar results in anesthesiologists who were tested on simulators. “Eyes closing, head nodding, and actual sleep” constituted “sleepy behaviors.” Interestingly, fatigued anesthesiologists experienced sleepy behaviors for over 30% of the time in a 4-h case!

It would be naïve not to confess that everyone experiences this behavior either in classroom, conference room, or the operation theatre. We all have been afflicted by different levels of sleepiness at various critical junctures in and out of hospital, which could have endangered our or someone else’s life. Practicing, under trainee, or nurse anesthesiologists have had inadvertent sleep deficit, cumulatively assimilated after long, strenuous, recurrent emergency calls, and/or night duties. While pushing our limits, we perch on top of the sleep debt “volcano,” which is waiting to burst and ensue in form of a clinical cataclysm.

Landrigan[22] studied interns in the ICU and evaluated their different schedules, which included the “customary” schedule, for work of up to 30 consecutive hours, and the “intervention” schedule which restricted the number of successive hours to <17. He observed residents on the abridged schedule obtained additional sleep and this manifested in 36% fewer errors and fewer “attentional failures,” which were actual electroencephalographic (EEG) episodes of sleepiness during patient care.

Epworth sleepiness score

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) introduced by Dr. Murray Johns (Epworth Hospital, Australia 1991) is a scale intended to measure daytime sleepiness by use of a very short questionnaire and is employed in diagnosing sleep disorders.[23] ESS is useful for preliminary evaluation and comparative measurements of professionals across the health care continuum. There is a high level of internal consistency between the eight items in the ESS as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, ranging from 0.74 to 0.88. The ESS is a subjective measure, which segregates between average sleepiness and excessive daytime sleepiness that necessitates intervention. The subject rates on how likely it is that he/she would doze in eight different situations encountered in their daily routine. Each answer is scored from 0 being “would never doze” up to 3 being “high chance of dozing.” A total score of 0-9 is considered normal, but a score between 10 and 24 reflects warrants medical intervention. ESS has been translated into various languages and is available online for use.[24] ESS has not been validated for telephonic interviews or for assessing variations in sleep over a span of hours. ESS has shown a high specificity (100%) and sensitivity (93.5%)[25] in patients with narcolepsy.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is a self-rated questionnaire which assesses sleep quality and disturbances over a 1-month time interval. It has a high test-retest reliability and good validity in primary insomnia.[26] Nineteen distinct items generate seven “component” scores: Subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. The sum of scores for these seven components produces one global score. The clinometric and clinical properties of the PSQI suggest its utility both in psychiatric clinical practice and research activities.[27]

Sleep disorders

Drake recently elaborated on “shift work sleep disorder” with an incidence of 10% in night and rotating shift work populations.[28] There are innumerous sleep disorders ranging from insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, abnormal movements, or breathing during sleep till death sudden deaths due to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Insomnia, periodic limb movements, and OSA are more rampant but still under diagnosed.

OSA is significantly prevalent in at least 3-5% of the population and is frequent in middle-aged males. It may be compounded with habitual snoring, large neck circumference, obesity, and excessive daytime sleepiness. An interesting analogy exists between a person with OSA and a resident on emergency call. OSA involves profound effort restarting sleep and is similar to the on call pager beeping many times every night.

Pathology due to fatigue

Insomnia was associated with mortality in men with short sleep duration, but not in men with “normal” sleep duration (Penn state cohort mortality data, 2010).[29] Similarly, a prospective research by the American Cancer Society in more than one million individuals found that men who had less than 4 h of daily sleep times were 2.8 times more likely to have died within a 6-year follow-up as compared to those who achieved 7-7.9 h of sleep whereas in women the risk was augmented by 48%.[30]

After nine consecutive hours of work, the risk for unintentional accident increases exponentially with each subsequent hour.[31] Fatigue leads to declined performance, attention span, and reaction time. Judgment becomes slow and precious time is lost in making critical choices. Decreased alertness and lapses in actions cause the provider to be more vulnerable to critical accidents and errors. Aging, night calls, intense schedules, and long working hour shifts all are stressful and contribute to onset of fatigue. Various studies have shown that as sleep debt increases the levels of cheerfulness and energy decrease, and simultaneously, there is increased confusion, anxiety, depression, anger, and fatigue. As work hours are protracted or extended into night, mood is negatively affected.[32–40]

Pilcher and Huffcutt[41] demonstrated that partial sleep deprivation had the greatest effect on mood and cognitive performance. Apart from the risks to care recipients, providers themselves suffer from ill effects of fatigue. Mood is archetypally assessed using various subjective scales, but effects of negative moods on patient care have not been measured directly.

Davis[42] found that women working the night shift had a 60% greater risk for breast cancer. Mozurkewich[43] in a meta-analysis of 29 studies, including more than 160,000 women, evaluated the association of physically demanding work, prolonged standing, long work hours, and cumulative “fatigue score.” He found evidence that these correlate with preterm delivery, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and small-for-gestational-age infants. Shift work alone was found to increase the incidence of preterm births. Several studies have shown that long-term exposure to shift work represents an independent risk factor for the development of gastrointestinal and cardiovascular diseases.[44–46]

Fatigue and anesthesiologists

It is obligatory that an anesthesiologist stays vigilant at every step of patient care. “Vigilance” is defined as the act of being alert and watchful, especially to avoid danger. It also means being sleeplessly watchful. The RAND study on anesthesia workforce trends stated that anesthesiologists work on an average of 63 h per week, of which 49 h are clinical; and nurse anesthetists work an average of 44 h per week, of which 37 h are clinical.[47] Vigilance constitutes a fundamental part of the motto/slogan of anesthesiology bodies worldwide. American Society of Anesthesiologists and Indian Society of Anesthesia embody the word vigilance in their seal and motto respectively. Sleep debt leads to fatigue and predisposes to lack of vigilance. Ironically then, fatigue becomes the ensuing pathology of vigilance.

The probable impact of sleep loss and fatigue among anesthesiologists received early attention in 1990’s.[48,49] More than 50% of anesthesia care providers admitted having committed an error in medical judgment that they attributed to fatigue in studies by Gaba[50] and Gravenstein.[51] Utilizing the critical incident method of evaluating anesthetic errors, Cooper et al. projected that fatigue was responsible in 6% of reported critical incidents of human error which lead to 80% of anesthetic mishaps.[52] In New Zealand, 86% of the anesthesiologists who responded to a survey self-confessed to being involved in a fatigue-related error, while 58% felt that they surpassed their self-defined limit for safe continuous administration of anesthesia.[53] Fatigue was the culprit in 152 out of 5600 cases (3%) reported in Australian Incident Monitoring Study[54] conducted from 1987 to 1997.

In a study by Berry et al., anesthesia trainee residents were assigned into three groups.[55] First were those who were in a typical general operating room rotation without any on-call period in the previous 48 h. While in the post-call condition, they were studied after a 24-h in-hospital call period while rotating on a clinically busy service such as obstetric anesthesia or the intensive care unit. The third condition, termed sleep extended, attempted to produce a truly rested control condition by permitting four consecutive nights of increased sleep. To quantify differences among the three conditions subjective measures and a standard physiologic measure of daytime sleepiness, the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) were used[56] demonstrating that increased sleep is the most direct intervention that can improve waking levels of alertness. They found no significant differences physiologic sleepiness between the baseline and post-call conditions which was interpreted as residents being chronically sleep deprived to the extent that their baseline condition were equivalent to a post-call level of sleepiness.

Second, they conferred that the “control” condition does not accurately reflect the rested state. In the extended condition, alertness levels were significantly increased compared with the baseline and post-call conditions. The subjects experienced sleepiness accompanying severe sleep loss and sleep disorders (i.e., sleep apnea and narcolepsy) to a normal range of alertness after four consecutive nights of increased sleep. These interpretations debunked studies that established equivalence of “baseline” condition to a “post-call” condition. Significant inconsistency between subjective reports of fatigue and objective measures of physiologic status was the third conclusion. Residents subjective rating of sleepiness when compared and determined by MSLT score to document their physiologic measure found that in more than half of the instances, residents conveyed to be awake, but were essentially sleeping.

Surveys evaluating work hours of anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists, residents, and practitioner anesthesiologists[57–59] found that residents work longer hours (60-70 h/week) than their nursing and physician specialist counterparts (47.5-52 h/week). In well-controlled, scientifically sound investigations that tested deficiency in performance secondary to fatigue using reality simulators, exhibited noteworthy reductions in the performance of sleep-deprived surgeons.[60,61] Sleep deprived surgeons were slower, less accurate and more prone to errors.

Evidence in literature pertaining to other healthcare specialties

A meta-analysis by Pilcher[62] concluded that all sleep-deprived subjects performed at a level 1.37 SDs lower than rested subjects, and the greatest effect was on mood and cognitive measures, with little change in motor performance. Performance on complex and long tasks was reduced more by short-term sleep deprivation than performance on simple, short tasks. The total sample (n = 1932) included both medical and nonmedical participants and measured the effects of sleep deprivation on performance. Partial sleep deprivation had the greatest effect on mood and cognitive performance when compared to either short- or long-term sleep deprivation.

Rogers[63] in one of the first and largest study on nurses documented that error rate increased three times when the nurses worked shifts longer than 12.5 h. Similarly, Trinkoff[64] observed an increased risk of occupational injuries to nurses if shifts exceeded 12 h.

Appropriate sleep increases satisfaction with work, decreases stress and sense of being “impaired.” Baldwin and Daugherty showed that good sleep decreased the feeling of being humiliated amongst residents.[65] Increased night sleep proportionately increased satisfaction with learning, more quality time with their teachers, and were able to work more confidently without supervision. Young adults are more prone to sleep disorders due to their tendency to avoid available sleep opportunities, delayed sleep phase syndrome, and mood disorders. Increased frequency of calls leads to decreased desire to participate in operative procedures in surgical residents.[66]

In 2003, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) ordained that duty hours for residents limit shifts to 30 h and 80 h per week. Yet, these limitations do not guarantee safety. Landrigan[67,68] found that if residents worked 24-h shifts recurrently, they were liable to make 36% serious preventable antagonistic events and five times as many serious diagnostic errors than individuals working up to 16-h shifts. The most alarming fact was that there were 300% more fatigue related preventable adverse events that led to a patient’s death. Pediatric residents who were sleep deprived were found to take significantly longer time in umbilical artery cannulation.[69] Simulated laparoscopic surgery[70] on post-call surgeons demonstrates a 20% increase in errors and 14% increase in time to accomplish a laparoscopic procedures.

Co-relation between long work hours with an increased potential for injury from accidents, especially exaggerated when extended work hours occur on a late shift. Residents and medical students are at 50% greater risk of exposure to blood borne pathogen. Needle stick injuries are the most frequent mode of injury by anesthesia providers usually due to carelessness from fatigue, particularly more during night than during days.[71]

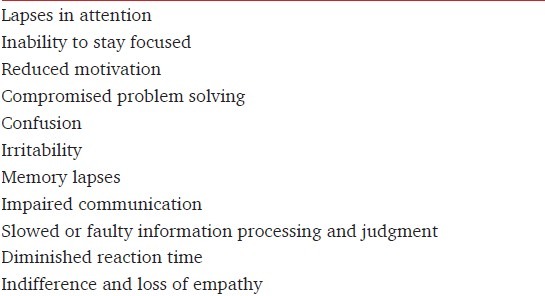

The Joint Commission (TJC) acknowledged the link between fatigue and adverse events and observed an unusual frequency of events which raised concern for patient safety and quality of patient care being delivered. A sentinel event pertaining to anesthesia is defined by TJC as one that may result in death or permanent loss of function. The data were based on analysis conducted by the organization, and the majority of events have multiple root causes. TJC issued a Sentinel event Alert titled “Health care worker fatigue and patient safety” (http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_48.pdf). The TJC policy in regard to sentinel events states that it reviews organization activities in response to sentinel events in its accreditation process as part of its mission to continuously improve safety and quality of health care to the public. Patients and health care workers can be harmed and efficiency diminished as a result of worker fatigue. While it acknowledges that the problem of fatigue is multifactorial, TJC focuses its alerts on the risks of an extended work day and accumulation of such extended days. Per TJC, fatigue can result from either an insufficient quantity of sleep or insufficient quality of sleep over extended period of time. Problems that can be exhibited include [Table 2].

Table 2.

Frequently observed problems resulting due to fatigue

How do anesthesiology organizations ensure that anesthesiologists have had adequate sleep, before putting their patients to sleep?

TJC has adequately advocated effective measures to be enforced by the hospital administration to preclude fatigue in their health care personnel. Their suggestions are as follows:

Awareness: First, make sure that the hospital highest authorities are aware of this Sentinel Event Alert and the various actions they could implement.

Evaluate Risks: Assess for fatigue-related risks, including off-shifts hours, consecutive shift work, and their respective policies and procedures. Also assess off-shift hours and consecutive shift work, and review staffing and other relevant policies to ensure they address extended work shifts and hours.

Assess hand-off process and procedures:[72] Since the time when there is least contact between the anesthesiologists and the patients is maximally prone to errors, especially in fatigued staff. It is essential that hands-off processes and procedures are assessed to ensure that patients remain safe all the time.

Staff Input: Encourage staff feedback in crafting safe work schedule and provide prospects for staff to express concerns about fatigue.

Fatigue Management Plan: Generate and enforce a fatigue management plan that includes strategies for fighting fatigue. This should not just be limited to passive hearing and nodding, but there should be an engaging fruitful conversation. Various fatigues alleviating methodology should be taught and encouraged to be followed, e.g., physical activity like stretching when tired, caffeine (do not use caffeine when you are already alert and avoid caffeine near bedtime); short naps not more than 45 min are best.[73,74] These strategies are derived from studies conducted by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which stresses that the only way to counteract the severe consequences of sleepiness is to sleep.

Sleep Breaks: Evaluate the milieu provided for sleep breaks to guarantee that it provides and safeguards adequate sleep. Ensure basic measures to ensure good quality sleep should include a cool, dark, quiet, comfortable room, and, if necessary, use of eye mask and ear plugs. Also include continual coverage of all responsibilities by another provider.

Educate staff about sleep hygiene and impacts on patient and worker safety. Sleep hygiene embraces attaining sufficient sleep and taking naps, practicing good sleep habits (e.g., engaging in a relaxing pre-sleep routine, such as yoga or reading), and avoiding food, alcohol, or stimulants (such as caffeine) that can impact sleep.

Propagate a safety culture: Ample openings must be allowed to the anesthesiology staff to voice and register apprehensions about fatigue. Try and acknowledge the appropriate concerns about fatigue and take remedial action to address those as soon as possible.

Teamwork: Enhance and encourage teamwork as a policy to support anesthesiologists that work protracted work shifts or hours thereby protecting patients from impending harm. For example, implement protocols for secondary checks and documentation by independent personal at critical junctures for critical tasks or complex patients.

Review and analyze: Consider fatigue as a potentially contributing factor when reviewing any adverse events. Take appropriate measure to avoid its reoccurrence.

Your own patients have become the enemy… because they are the one thing that stands between you and a few hours of sleep

Papp et al., Academic Medicine, 2002

Time to wake up

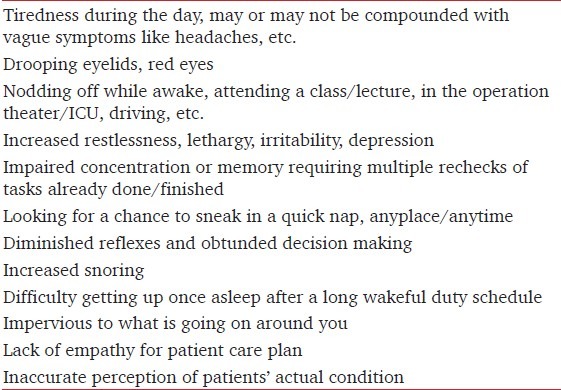

The first step would be to be honest and acknowledge that fatigue in anesthesia providers is an issue that needs urgent appraisal. If patients’ safety is our ulterior motive then let us not be naïve to jeopardize it by being oblivious to the impact of sleep deficit. Fatigue induced by sleeplessness is both personally and professionally detrimental. Our body always gives us clues that suggest privation of sleep [Table 3]. We need to pay attention to these sentinel signs and ensure a remedial action. We must begin identifying signs of sleepiness and fatigue in self and others as well. Monitoring plans and strategies to deal with it must be in place in each institution and workplace.

Table 3.

Clues suggesting that you are sleepy and should not be ignored

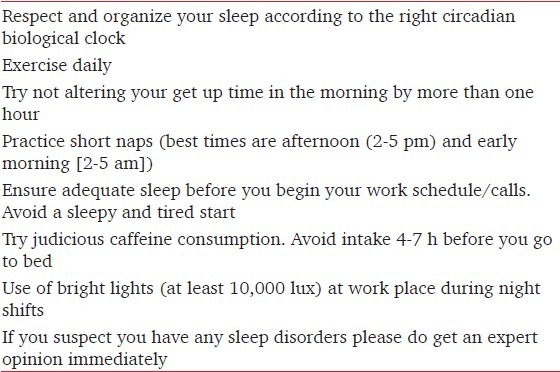

There are many simple things that may help us tide over the feeling of fatigue due to sleeplessness [Table 4]. Frequent napping also enhances vigilance. Catnaps just before starting a call or shift are preferable than napping on the job. Short naps should be restricted to less than half an hour to avoid sleep inertia.[75] Use of caffeine (peak affect in 15-30 min and half-life of 3-7 h) in a dose of 75-150 mg may reduce some sleep deficits. Moderate and judicious use may provide temporary relief for somnolence, but its abuse may lead to more arousals during sleep, diuresis, and setting in of tolerance.[76] Use of amphetamines or MPH (10-20 mg) or Modafinil (100-400 mg) may improve alertness and psychomotor performance but may result in cardiovascular/metabolic/neuroendocrine disturbances and cause unpredictable adverse sleep effects and cannot be routinely recommended.

Table 4.

Simple steps to avoid fatigue

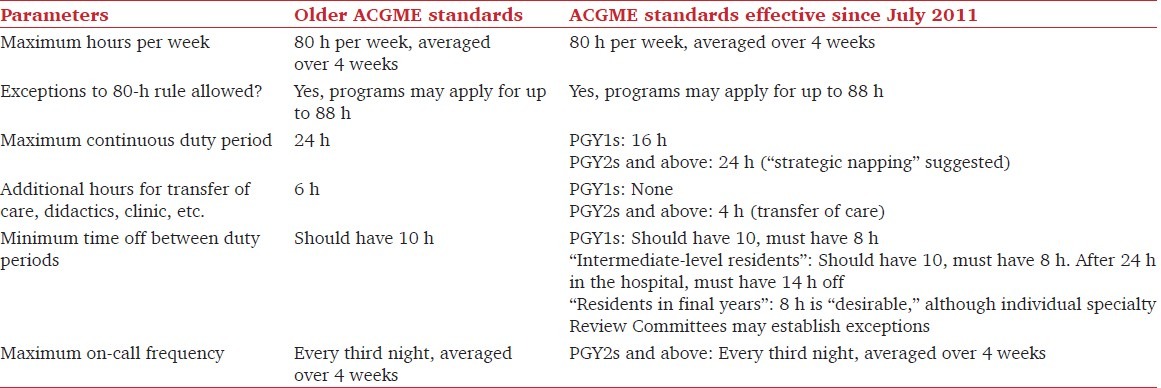

August 2009 saw the full implementation of the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) into UK legislation, including doctors in training. This prescribes a maximum of 48-56 h per week and only 13 consecutive work hours. EWTD limits doctors in training to a maximum 48-h week, averaged over a 6 months period. It lays down minimum requirements in relation to working hours, rest periods and annual leave. In the southern hemisphere, the New Zealand Employer - Resident Contract restricts duty hours to a maximum of 72 h weekly and only 16 consecutive hours are permissible. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) released Common Program Requirements further restricting the duty hours of the over 100,000 residents training in ACGME-accredited residency programs in the United States [Table 5]. The new criterions also require increased supervision of residents and set forth specific requirements for alertness management and fatigue extenuation. Most notably, the maximum continuous duty period for PGY1s (first year residents) has been reduced to 16 h. PGY2s and above may work 24 continuous hours, with an additional 4 h permitted for hand-offs, but “strategic napping” is suggested.

Table 5.

New ACGME guidelines (PGY=Postgraduate year)

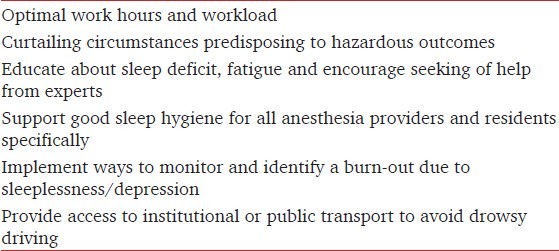

There are various regulations in place in USA which prescribe work hours. Truckers can only drive continuously for a maximum of 11 h. Airline pilots can fly on domestic routes for no more than 8 h in 24 h. Nuclear plant workers and train engineers can only work for a maximum of a 12 h shift. Efforts have to be implemented at the national level in India to ensure that we counter the menace of fatigue due to sleeplessness affecting appropriate patient care. A few of possible endeavors that can be implements right away are enumerated in Table 6.

Table 6.

Proposed steps at the institutional or national level

Conclusion

Are we applying the results from scientific studies and advocating a practice that ensures safety for the health of our patients and us as anesthesiology practitioner? It is time to wake up from our animated slumber, least we compromise our motto: “eternal vigilance.”[77] A paradigm shift is required to adopt new tools and strategies in dealing with sleep loss and fatigue in our fraternity. Anesthesiologists need to be alert and healthy to render the best possible care to patients and themselves. Evidence abounds demonstrating beyond doubt that the impact of fatigue on mood as well as psychomotor and cognitive performance. The participants in most studies have been residents rather than older practitioners, and therefore, the interaction between fatigue and aging remains unknown and must be elucidated. The current archetype of work scheduling for nonresident anesthesiologists has generally remained unchanged, although the healthcare environment has undergone radical alterations over the past decade. As the public and federal agencies advocate practices to make health care safer, we should no longer ignore the accumulating body of data regarding the effects of fatigue and sleep deprivation on performance.

It is time we recognize sleepiness, the impact of sleep loss and fatigue caused by it on our personal and professional lives because this will affect our own and our patient’s safety.

“Patients have a right to expect a healthy, alert, responsible, and responsive physician.”

January 1994 statement by American College of Surgeons

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Krueger GP. Sustained work, fatigue, sleeps loss and performance: A review of the issues. Work Stress. 1989;3:129–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brendel DH, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Jennings JR, Hoch CC, Monk TH, Berman SR, et al. Sleep stage physiology, mood, and vigilance responses to total sleep deprivation in healthy 80-year-olds and 20-year-olds. Psychophysiology. 1990;27:677–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb03193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinges DF, Pack F, Williams K, Gillen KA, Powell JW, Ott GE, et al. Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 hours per night. Sleep. 1997;20:267–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fatigue in Aviation. FAA Pilot Safety Brochure Medical Facts for Pilots, Pub # OK-07-193. Aviation Medicine Advisory Service-NBAA. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flight crew member duty and rest requirements. FAA NPRM Docket No. FAA-2009-1093; Notice No. 10-11, Federal Register 16 Sep 2010. Aviation Medicine Advisory Service-NBAA. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lydic R, Schoene WC, Czeisler CA, Moore-Ede MC. Suprachiasmatic region of the human hypothalamus: Homolog to the primate circadian pacemaker? Sleep. 1980;2:355–61. doi: 10.1093/sleep/2.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czeisler CA, Khalsa SB. In: The human circadian timing system and sleepwake regulation, Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 3rd ed. Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000. pp. 353–75. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akerstedt T, Kecklund G. Age, gender and early morning highway accidents. J Sleep Res. 2001;10:105–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akerstedt T, Kecklund G, Horte LG. Night driving, season, and the risk of highway accidents. Sleep. 2001;24:401–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aya AG, Mangin R, Robert C, Ferrer JM, Eledjam JJ. Increased risk of unintentional dural puncture in night-time obstetric epidural anesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:665–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03013955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rechtschaffen A, Bergmann BM. Sleep deprivation in the rat: An update of the 1989 paper. Sleep. 2002;25:18–24. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Nocturnal determinants of daytime sleepiness. Sleep. 1982;5:S73–81. doi: 10.1093/sleep/5.s2.s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wehr TA, Moul DE, Barbato G, Giesen HA, Seidel JA, Barker C, et al. Conservation of photoperiod-responsive mechanisms in humans. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R846–57. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.4.R846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonnet MH. In: Sleep deprivation, Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 3rd ed. Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000. pp. 53–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kripke DF, Simons RN, Garfinkel L, Hammond EC. Short and long sleep and sleeping pills. Is increased mortality associated? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:103–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780010109014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Dongen HP, Maislin G, Mullington JM, Dinges DF. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2003;26:117–26. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bliwise DL. Normal aging. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 24–38.pp. 2 [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Classification of Sleep Disorders Diagnostic and Coding Manual. [Last assessed on 2012 Sep 06]. Available from: http://www.esst.org/adds/ICSD.pdf .

- 19.Blaivas AJ, Patel R, Hom D, Antigua K, Ashtyani H. Quantifying microsleep to help assess subjective sleepiness. Sleep Med. 2007;8:156–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lockley SW, Cronin JW, Evans EE, Cade BE, Lee CJ, Landrigan CP, et al. Effect of reducing interns’ weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failures. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1829–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard SK, Gaba DM, Smith BE, Weinger MB, Herndon C, Keshavacharya S, et al. Simulation study of rested versus sleep-deprived anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1345–55. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200306000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Burdick E, Katz JT, et al. Effect of reducing interns’ work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1838–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johns MW. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale: The Official Website of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 16]. Available from: http://epworthsleepinessscale.com/about-epworth-sleepiness/

- 25.Johns MW. Sensitivity and specificity of the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT), the maintenance of wakefulness test and the Epworth sleepiness scale: Failure of the MSLT as a gold standard. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:5–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:737–40. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drake CL, Roehrs T, Richardson G, Walsh JK, Roth T. Shift work sleep disorder: Prevalence and consequences beyond that of symptomatic day workers. Sleep. 2004;27:1453–62. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Pejovic S, Calhoun S, Karataraki M, Basta M, et al. Insomnia with short sleep duration and mortality: the Penn State cohort. Sleep. 2010;33:1159–64. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kripke DF, Simons RN, Garfinkel L, Hammond EC. Short and long sleep and sleeping pills: Is increased mortality associated? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:103–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780010109014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanecke K, Tiedemann S, Nachreiner F, Grzech-Sukalo H. Accident risk as a function of hour at work and time of day as determined from accident data and exposure models for the German working population. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartle EJ, Sun JH, Thompson L, Light AI, McCool C, Heaton S. The effects of acute sleep deprivation during residency training. Surgery. 1988;104:311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart RP, Buchsbaum DG, Wade JB, Hamer RM, Kwentus JA. Effect of sleep deprivation on first-year residents’ response times, memory, and mood. J Med Educ. 1987;62:940–2. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198711000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubin R, Orris P, Lau SL, Hryhorczuk DO, Furner S, Letz R. Neurobehavioral effects of the on-call experience in house staff physicians. J Occup Med. 1991;33:13–8. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Light AI, Sun JH, McCool C, Thompson L, Heaton S, Bartle EJ. The effects of acute sleep deprivation on level of resident training. Curr Surg. 1989;46:29–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wesnes KA, Walker MB, Walker LG, Heys SD, White L, Warren R, et al. Cognitive performance and mood after a weekend on call in a surgical unit. Br J Surg. 1997;84:493–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leonard C, Fanning N, Attwood J, Buckley M. The effect of fatigue, sleep deprivation and onerous working hours on the physical and mental wellbeing of pre-registration house officers. Iran J Med Sci. 1998;167:22–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02937548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lingenfelser T, Kaschel R, Weber A, Zaiser-Kaschel H, Jakober B, Kuper J. Young hospital doctors after night duty: Their task-specific cognitive status and emotional condition. Med Educ. 1994;28:566–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1994.tb02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orton DI, Gruzelier JH. Adverse changes in mood and cognitive performance of house officers after night duty. BMJ. 1989;298:21–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6665.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Browne BJ, Van Susteren T, Onsager DR, Simpson D, Salaymeh B, Condon RE. Influence of sleep deprivation on learning among surgical house staff and medical students. Surgery. 1994;115:604–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akerstedt T. Consensus statement: Fatigue and accidents in transport operations. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:395. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis S, Mirick DK, Stevens RG. Night shift work, light at night, and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1557–62. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.20.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mozurkewich EL, Luke B, Avni M, Wolf FM. Working conditions and adverse pregnancy outcome: A meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:623–35. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vener KJ, Szabo S, Moore JG. The effect of shift work on gastrointestinal (GI) function: A review. Chronobiologia. 1989;16:421–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson G, Tate B. Hormonal and pharmacological manipulation of the circadian clock: Recent developments and future strategies. Sleep. 2000;23:S77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knutsson A, Boggild H. Shiftwork and cardiovascular disease: Review of disease mechanisms. Rev Environ Health. 2000;15:359–72. doi: 10.1515/reveh.2000.15.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daugherty L, Fonseca R, Kumar KB, Michaud PC. An analysis of the labor markets for anesthesiology. Santa Monica, Calif: RAND Corporation; 2010. [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 16]. TR-688-EES, Available from: http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR688.html . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parker JB. The effects of fatigue on physician performance: An underestimated cause of physician impairment and increased patient risk. Can J Anaesth. 1987;34:489–95. doi: 10.1007/BF03014356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinger MB, Englund CE. Ergonomic and human factors affecting anesthetic vigilance and monitoring performance in the operating room environment. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:995–1021. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199011000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaba DM, Howard SK, Jump B. Production pressure in the work environment: California anesthesiologists’ attitudes and experiences. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:488–500. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199408000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gravenstein JS, Cooper JB, Orkin FK. Work and rest cycles in anesthesia practice. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:737–42. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199004000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooper JB, Newbower RS, Long CD, McPeek B. Preventable anesthesia mishaps: A study of human factors. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:399–406. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gander PH, Merry A, Millar MM, Weller J. Hours of work and fatigue related error: A survey of New Zealand anaesthetists. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:178–83. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0002800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris GP, Morris RW. Anaesthesia and fatigue: An analysis of the first 10 years of the Australian Incident Monitoring Study 1987-1997. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:300–4. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0002800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berry AJ, Hall JR. Work hours of residents in seven anesthesiology training programs. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:96–101. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199301000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carskadon MA, Dement WC, Mitler MM, Roth T, Westbrook PR, Keenan S. Guidelines for the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT): A standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep. 1986;9:519–24. doi: 10.1093/sleep/9.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gander PH, Merry A, Millar MM, Weller J. Hours of work and fatigue related error: A survey of New Zealand anaesthetists. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:178–83. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0002800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gravenstein JS, Cooper JB, Orkin FK. Work and rest cycles in anesthesia practice. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:737–42. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199004000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dercq JP, Smets D, Somer A, Desantoine D. A survey of Belgian anesthesiologists. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 1998;49:193–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grantcharov TP, Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Rosenberg J. Laparoscopic performance after one night on call in a surgical department: Prospective study. BMJ. 2001;323:1222–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7323.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taffinder NJ, McManus IC, Gul Y, Russell RC, Darzi A. Effect of sleep deprivation on surgeons’ dexterity on laparoscopy simulator (research letter) Lancet. 1998;352:1191. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pilcher JJ, Huffcutt AI. Effects of sleep deprivation on performance: A meta-analysis. Sleep. 1996;19:318–26. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rogers AE, Hwang WT, Scott LD, Aiken LH, Dinges DF. The working hours of hospital staff nurses and patient safety. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:202–12. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trinkoff AM, Le R, Geiger-Brown J, Lipscomb J. Work schedule, needle use, and needle stick injuries among registered nurses. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:156–64. doi: 10.1086/510785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baldwin DC, Jr, Daugherty SR. Sleep deprivation and fatigue in residency training: Results of a national survey of first- and second-year residents. Sleep. 2004;27:217–23. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sawyer RG, Tribble CG, Newberg DS, Pruett TL, Minasi JS. Intern call schedules and their relationship to sleep, operating room participation, stress, and satisfaction. Surgery. 1999;126:337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Landrigan CP, Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, Czeisler CA. Interns’ compliance with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education work-hour limits. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;296:1063–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Landrigan CP, Fahrenkopf AM, Lewin D, Sharek PJ, Barger LK, Eisner M, et al. Effects of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty hour limits on sleep, work hours, and safety. Pediatrics. 2008;122:250–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Storer JS, Floyd HH, Gill WL, Giusti CW, Ginsberg H. Effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive ability and skills of pediatrics residents. Acad Med. 1989;64:29–32. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198901000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grantcharov TP, Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Rosenberg J. Laparoscopic performance after one night on call in a surgical department: Prospective study. BMJ. 2001;323:1222–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7323.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parks DK, Yetman RJ, McNeese MC, Burau K, Smolensky MH. Day-night pattern in accidental exposures to blood-borne pathogens among medical students and residents. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:61–70. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blum AB, Shea S, Czeisler CA, Landrigan CP, Leape L. Implementing the 2009 Institute of Medicine recommendations on resident physician work hours, supervision, and safety. Nat Sci Sleep. 2011;3:1–39. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S19649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Co EL, Gregory KB, Johnson JM, Rosekind MR. Fatigue Countermeasures: Alertness Management in Flight Operations. Long Beach, Calif: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Southern California Safety Institute Proceedings; 1994. [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 16]. Available from: http://human-factors.arc.nasa.gov/zteam/fcp/pubs/scsi.html . [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosekind MR, Gander PH, Connell LJ, Co EL. Fatigue Countermeasures: Alertness Management in Flight Operations. Long Beach, Calif: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Southern California Safety Institute Proceedings; 1994. [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 16]. Available from: http://human-factors.arc.nasa.gov/zteam/fcp/pubs/scsi.html . [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tietzel AJ, Lack LC. The short-term benefits of brief and long naps following nocturnal sleep restriction. Sleep. 2001;24:293–300. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bonnet MH, Balkin TJ, Dinges DF, Roehrs T, Rogers NL, Wesensten NJ Sleep Deprivation and Stimulant Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The use of stimulants to modify performance during sleep loss: A review by the sleep deprivation and Stimulant Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep. 2005;28:1163–87. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tewari A, Soliz J, Billota F, Garg S, Singh H. Does our sleepdebt affect patients’ safety? Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:12–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.76572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]