Abstract

Background:

Idiopathic gingival enlargement is a rare condition characterized by massive enlargement of the gingiva. It may be associated with other diseases/conditions characterizing a syndrome, but rarely associated with periodontitis.

Case Description:

This case report describes an unusual clinical form of gingival enlargement associated with chronic periodontitis. Clinical examination revealed diffuse gingival enlargement. The lesion was asymptomatic, firm, and pinkish red. Generalized periodontal pockets were observed. Radiographic evaluation revealed generalized severe alveolar bone loss. Histopathological investigations revealed atrophic epithelium with dense fibrocollagenous tissue. Lesions healed successfully following extraction and surgical excision, and no recurrence was observed after 1 year follow-up but recurrence was observed at 3 and 5-years follow-up.

Clinical Implications:

Successful treatment of idiopathic gingival enlargement depends on proper identification of etiologic factors and improving esthetics and function through surgical excision of the over growth. However, there may be recurrence.

Keywords: Chronic periodontitis, dense collagenous tissue, idiopathic enlargement

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic gingival enlargement is a rare condition of unknown etiology characterized by slow, progressive enlargement of the gingiva. It is also known as elephantiasis, idiopathic fibromatosis, gingivomatosis, and hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF).[1,2,3,4] It may occur as an isolated disorder or may be associated with conditions like tuberous sclerosis,[5] and hypertrichosis.[6] Various drugs such as calcium channel blockers,[7] immunosuppressants,[8] and anticonvulsants[9] can lead to massive gingival enlargement. It may also occur as a part of syndromes like Zimmerman–Laband syndrome,[10,11] Jones syndrome,[12] Murray-Peretic-Drescher syndrome,[13] cherubism,[14] Cross syndrome,[15] Ramon syndrome,[16] and Prune belly syndrome.[17] HGF can also lead to massive gingival enlargement. The characteristics most frequently associated with HGF are hypertrichosis, mental retardation, epilepsy, hearing loss, supernumerary teeth, and abnormalities of the fingers and toes.[3,18]

The enlarged gingiva is pink in color, firm in consistency, with abundant stippling, and has a characteristic pebbled surface that is asymptomatic.[19] Males and females are equally affected at a phenotype frequency of 1:175,000.[20] This anomaly is classified as two types according to its form. The localized nodular form is characterized by the presence of multiple enlargements in the gingiva. The most common symmetric form results in uniform enlargement of the gingiva.[4] Hyperplastic gingival enlargement may occur during or after the eruption of primary or permanent dentition and rarely present at birth.[12,19] The most common effect related to gingival enlargement is malpositioning of teeth, diastemas, and prolonged retention of primary teeth. In cases of massive enlargement the teeth are completely submerged, and the enlargement projects into the oral vestibule resulting in facial disfigurement, difficulty in mastication, and speech.[3,19,21]

Histologically, epithelium appears hyperplastic with elongated ret pegs. There is a marked increase in the amount of connective tissue which is relatively avascular and presents bundles of collagen fibers running in all directions and numerous fibroblasts.[1,22,23] Mild chronic inflammatory infiltrates are also observed in subepithelial connective tissue. Small calcified particles, ulceration of overlying mucosa, amyloid deposits, osseous metaplasia, and islands of odontogenic epithelium have also been reported.[24] Although gingival enlargement may increase bacterial plaque accumulation, the alveolar bone is not affected.[4]

Chronic periodontitis is the most common form of periodontitis.[25] Although it is more prevalent in adults, it can occur in children and adolescents in response to local factors such as plaque and calculus. Chronic periodontitis has a slow to moderate rate of disease progression, but periods of more rapid destruction may be observed. Various factors have been identified which increases the risk of developing chronic periodontitis.[26] Based on the amount of clinical attachment loss, chronic periodontitis may be described as slight, moderate, or severe.

Treatment of idiopathic gingival enlargement consists of surgical excision[22] of the hyperplastic tissue to restore gingival contours, but the recurrence rate is very high following surgical excision.[27,28] Usually, these types of enlargements are associated with minimal local factors and minimal alveolar bone loss; however, there have been few reports on this rare lesion where it was associated with aggressive periodontitis.[29,30] In this report, we present an unusual case of a nonsyndromic; idiopathic gingival enlargement associated with chronic periodontitis and discuss the clinical and histopathological features. No other case with such an association has been reported to date.

CASE REPORT

A 30-year-old male reported to the outpatient department of Periodontics, SDMCDSH, Dharwad, India, with the complaint of swollen and bleeding gums, foul breath, and esthetic deformities of face. Patient noticed swollen gums 2 years back. Since it was asymptomatic, patient neglected it. The lesion started as a small painless, beadlike enlargement. As the enlargement progressed it resulted into a massive tissue fold covering considerable portion of the crowns, interfering with mastication and speech. Besides these, no other complaints were present, such as pain. Patient's past dental, medical, and drug history were non-contributory. Further questioning revealed that none of his family members were affected with any form of gingival enlargement, nor was there any familial history of aggressive periodontitis, hypertrichosis, mental retardation, or epilepsy. All the parameters in the hematological investigations were within normal limits. His height and weight were within normal limits.

Extraoral examination revealed asymmetry of the face but there were no findings of lymphadenopathy. Intraoral examination revealed massive, generalized diffuse type of gingival enlargement involving both maxillary and mandibular arches, encroaching buccal, palatal, and lingual vestibular spaces [Figure 1a-c]. The lesion extended up to the level of occlusal plane. Gingiva was pale pink and firm in consistency with pebbled surface. No signs of acute inflammation were present. In addition, halitosis was accentuated. Periodontal examination revealed the presence of a thick band of microbial dental plaque and calculus subgingivally, generalized bleeding on probing, generalized mobility of teeth, malpositioning of upper anteriors, and generalized probing pocket depth in the range of 7 and 10 mm [Figure 2a and b]. Consistent with these findings, panoramic radiograph revealed severe generalized alveolar bone loss indicating severe form of periodontal disease [Figure 3]. Examination of immediate family members of the patient revealed that, none of his family members were affected with severe form of periodontal disease suggesting a negative history for aggressive periodontal disease, confirming recorded history. Histopathological investigations of the excised tissue revealed atrophic parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with the dense avascular fibrocollagenous tissue [Figure 4].

Figure 1.

(a) Intraoral clinical appearance showing generalized gingival enlargement involving both maxillary and mandibular arches with obliteration of buccal vestibular space. (b) Enlargement of palatal gingiva (c) Gingival enlargement obliterating lingual vestibular space

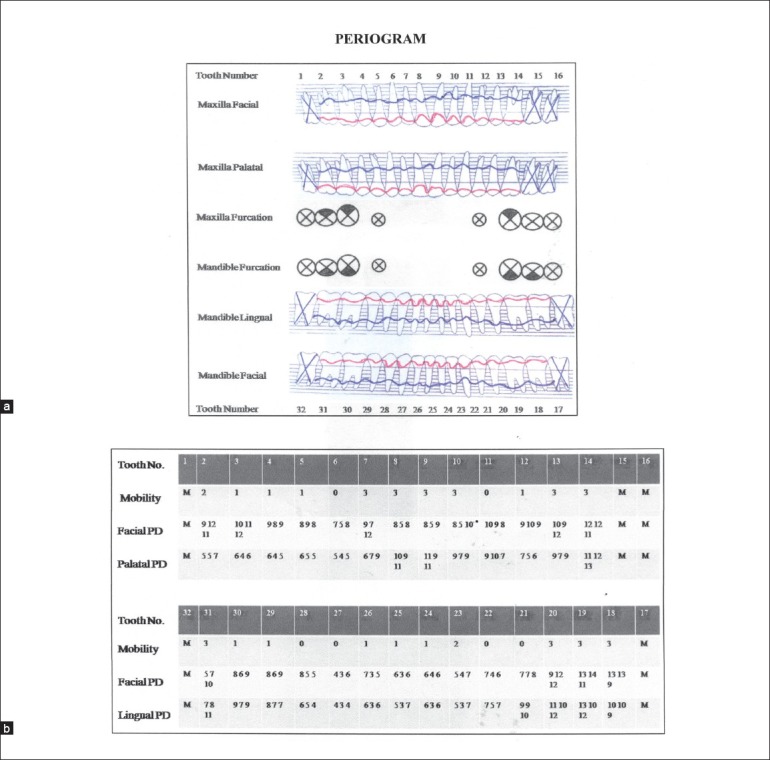

Figure 2.

(a) Periogram showing the bone (blue) and gingival (red) profiles of the subject before periodontal therapy (b) Table showing tooth mobility, facial and lingual probing depths, based on the clinical measurements of the subject before periodontal therapy

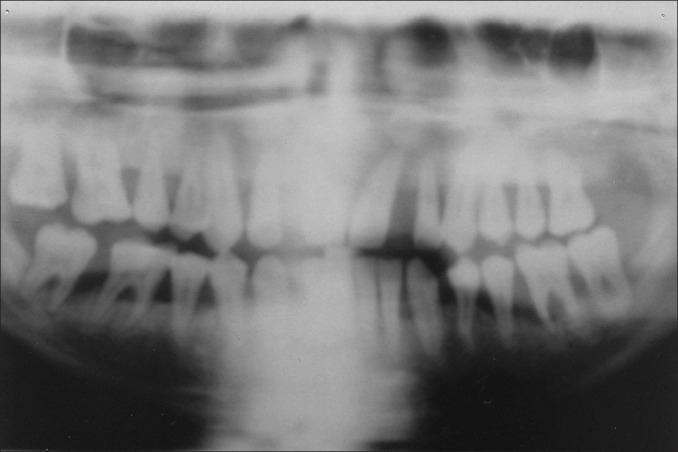

Figure 3.

Panoramic radiograph showing severe generalized alveolar bone loss

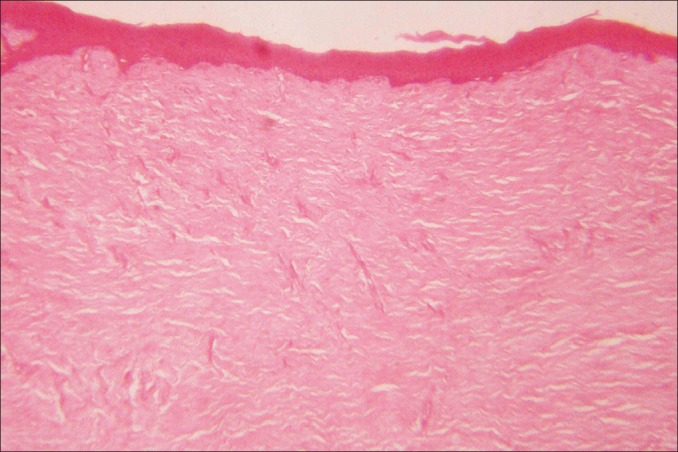

Figure 4.

Histological examination of excised gingival tissue shows dense fibrocollagenous tissue underlying an atrophic epithelium (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×100)

In the present case, the enlargement was not related to hereditary, syndromes, drugs, conditions, or endocrine problems. Severity of gingival enlargement was not consistent with the amount of local factors present and the presence of local factors might be secondary to gingival enlargement, as massive gingival enlargement interferes with proper oral hygiene. Histological examination of the excised tissue was suggestive of non-inflammatory gingival enlargement. Based on the history, clinical, radiological, and histopathological examination, a diagnosis of idiopathic gingival enlargement with generalized chronic periodontitis was made.

Eleven teeth were extracted due to hopeless prognosis. Examination of extracted teeth revealed root resorption of molars and the presence of thick band of subgingival calculus covering the entire length of the roots. Clinical inflammation was minimal after scaling and root planing. Surgical therapy included internal bevel gingivectomy combined with the open flap debridement under local anesthesia, which was performed at an interval of 1 month. The recovery period was uneventful. Function and esthetics were restored early with removable partial dentures. The patient showed no evidence of recurrence during 1 year follow-up period [Figure 5]. Three more teeth were extracted due to hopeless prognosis at 3 years follow-up and scaling was done for the remaining teeth. At the most recent follow-up, 5 years after the procedure, recurrence of the gingival enlargement was observed in the lower right quadrant, and anteriors [Figure 6]. The appearance of the tissue was quite similar to that seen at the beginning. Re-evaluation revealed the presence of plaque and calculus and periodontal pockets.

Figure 5.

No evidence of recurrence of gingival enlargement at 1 year postoperative presentation

Figure 6.

Recurrence of gingival enlargement at 5 year postoperative presentation

DISCUSSION

Massive gingival enlargement is frequently associated with various drugs, conditions, syndromes, and hereditary disorders.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] There have been few reports on this rare lesion where it was associated with aggressive periodontitis[29,30] but has not been reported in coexistence with chronic periodontitis. The present report describes a case of idiopathic gingival enlargement with chronic periodontitis. Clinically and histologically, it is difficult to differentiate between idiopathic, hereditary, and drug induced gingival enlargement. In the present case diagnosis of idiopathic gingival enlargement with chronic periodontitis was made, because the enlargement was not related to hereditary, syndromes, drugs, conditions, or endocrine problems. The presence of thick band of subgingival calculus, deep periodontal pockets, mobility, malpositioning of teeth, and negative family history for severe form of periodontal disease supports the diagnosis of chronic periodontitis.[25,26,29,30] Histological appearance of the surgically removed tissue supports the diagnosis of idiopathic gingival enlargement.[22,23]

The cellular and molecular mechanisms that lead to this condition are not clear. Few authors observed that the proliferation rate is lower in HGF fibroblasts compared to normal gingiva controls.[31] But, recent studies have shown that fibroblasts from these types of gingival enlargement proliferate faster than those of normal gingiva.[18,23] Recently, role of sex hormones have been suggested in gingival enlargement.[32] According to few reports the increase in collagen synthesis and other extracellular matrix components, such as fibronectin and glycosaminoglycans,[18,23] and decreased levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1 and MMP-2) may be involved in gingival enlargement.[33]

Some authors report an increase in the proliferation of gingival fibroblasts by transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1),[23] whereas others report less than normal growth.[31] TGF-β1, stimulates the synthesis of type I collagen and reduces the degradation of extracellular matrix, which is thought to play a major role in gingival fibromatosis.[18] TGF-β1 reduces proteolytic activities of fibroblasts, favoring the accumulation of extracellular matrix components,[33] and it upregulates fibroblast proliferation and downregulates MMP-1 and MMP-2 expression by gingival fibroblasts in an autocrine fashion.[18] These data suggest that TGF-β1 is a key regulator of the biochemical mechanisms associated with the pathogenesis of gingival overgrowth induced by HGF. Furthermore, TGF-β1 enhances fibroblast proliferation, not only by increasing the G1/S transition and DNA synthesis but also by shortening the G1 phase of the cell cycle.[34] More studies are needed to clearly understand the etiopathogenesis of idiopathic gingival enlargement.

Treatment varies according to the degree of severity. When the enlargement is minimal, good scaling and home care maintenance may be sufficient. When the enlargement is massive, surgical excision is required to restore function and esthetics.[22] Extraction of all teeth and reduction of alveolar bone have been recommended in the past.[19,35,36] Various techniques used for the excision of the enlarged tissues include internal or external bevel gingivectomy, electrocautery, and carbon dioxide lasers.[2,3,19,21,22,37] Because of the severity of gingival enlargement and the presence of deep periodontal pockets in the present case, an internal bevel gingivectomy with open flap debridement was done under local anesthesia 1 month following the extraction of teeth with hopeless prognosis. Patient was advised to use 0.2% chlorhexidine oral rinse twice a day for 2 weeks after each surgery. Function and esthetics were restored early with removable partial dentures.

The surgical therapy is well known for improving the quality of patients’ life, as the removal of gingival over growth facilitates eating, speech, improves esthetics, and the access for plaque control. The local and psychological benefits, even though temporary, must not be underestimated and may outweigh the recurrence. Reports about recurrence rates are conflicting,[27,35,36] with several reporting no recurrence observed over a period of 2-5 years.[4,22,24] In the present case the patient showed no evidence of recurrence during 1 year follow-up period, but recurrence was first evident at 3 years follow-up, as the patient did not return periodically for check-up after 1 year follow up. Previous studies have demonstrated that recurrence is faster in areas of poor plaque control.[3,22] However, a study demonstrated that the degree of enlargement did not appear to be related to the oral hygiene or to the amount of calculus present and that a correct physiologic contour of the marginal gingiva is more important to prevent recurrence.[38] Normally, recurrence is minimal or delayed if good oral hygiene is achieved by a combination of monthly examinations with professional cleaning and oral hygiene instructions. Three more teeth were extracted due to hopeless prognosis at 3 year follow-up and scaling was done for remaining teeth. At the most recent follow-up, 5 years after the procedure, recurrence of the gingival enlargement was observed. The recurrence was observed only in the dentulous areas of the mouth as patient failed to maintain good oral hygiene.[27,35]

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first report of an unusual coexistence of non-syndromic idiopathic gingival enlargement with chronic periodontitis. Successful treatment of idiopathic gingival enlargement depends on the proper identification of etiologic factors and improving oral hygiene status, esthetics, and function through elimination of local factors and surgical excision of the over growth. However, recurrence may occur.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Anirudh B Acharya, Professor, from the Department of Periodontics, S.D.M College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Dharwad, Karnataka, India, for the suggestions in preparation of the manuscript. This study was not funded by any commercial organization or firm in the form of grants, equipment, drugs, or other.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lobao DS, Silva LC, Soares RV, Cruz RA. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis: A case report. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:699–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zackin SJ, Weisberger D. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: Report of a family. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1961;14:828–36. doi: 10.1016/s0030-4220(61)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baptista IP. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: A case report. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:871–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bittencourt LP, Campos V, Moliterno LF, Ribeiro DP, Sampaio RK. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: Review of the literature and a case report. Quintessence Int. 2000;31:415–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas D, Rapley J, Strathman R, Parker R. Tuberous sclerosis with gingival overgrowth. J Periodontol. 1992;63:713–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horning GM, Fisher JG, Barker BF, Killoy WJ, Lowe JW. Gingival fibromatosis with hypertrichosis: A case report. J Periodontol. 1985;56:344–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.6.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heijl L, Sundin Y. Nitrendipine-induced gingival overgrowth in dogs. J Periodontol. 1989;60:104–12. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomason JM, Seymour RA, Ellis JS, Kelly PJ, Parry G, Dark J, et al. Determinants of gingival overgrowth severity in organ transplant patients: An examination of the role of HLA phenotype. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:628–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato T, Okahashi N, Kawai S, Kato T, Inaba H, Morisaki I, et al. Impaired degradation of matrix collagen in human gingival fibroblasts by the antiepileptic drug phenytoin. J Periodontol. 2005;76:941–50. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holzhausen M, Ribeiro FS, Gonçalves D, Correa FO, Spolidorio LC, Orrico SR. Treatment of gingival fibromatosis associated with Zimmermann-Laband syndrome. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1559–62. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.9.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holzhausen M, Gonçalves D, Correa Fde O, Spolidorio LC, Rodrigues VC, Orrico SR. A case of Zimmermann-Laband syndrome with supernumerary teeth. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1225–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wynne SE, Aldred MJ, Bartold PM. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis associated with hearing loss and supernumerary teeth: A new syndrome. J Periodontol. 1995;66:75–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piattelli A, Scarano A, Di Bellucci A, Matarasso S. Juvenile hyaline fibromatosis of gingiva: A case report. J Periodontol. 1996;67:451–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yalcin S, Yalcin F, Soydinc M, Palanduz S, Gunhan O. Gingival fibromatosis combined with cherubism and psychomotor retardation: A rare syndrome. J Periodontol. 1999;70:201–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cross HE, McKusick VA, Breen W. A new oculocerebral syndrome with hypopigmentation. J Pediatr. 1967;70:398–406. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(67)80137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramon Y, Berman W, Bubis JJ. Gingival fibromatosis combined with cherubism. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1967;24:435–48. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(67)90416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison M, Odell EW, Agrawal M, Saravanamuttu R, Longhurst P. Gingival fibromatosis with prune-belly syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:304–7. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Andrade CR, Cotrin P, Graner E, Almeida OP, Sauk JJ, Coletta RD. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 autocrine stimulation regulates fibroblast proliferation in hereditary gingival fibromatosis. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1726–33. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.12.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bozzo L, Machado MA, de Almeida OP, Lopes MA, Coletta RD. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: Report of three cases. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2000;25:41–6. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.25.1.e254616x22403280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher J. Gingival abnormalities of genetic origin: A preliminary communication with special reference to hereditary generalized gingival fibromatosis. J Dent Res. 1966;45:597–612. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howe LC, Palmer RM. Periodontal and restorative treatment in a patient with familial gingival fibromatosis: A case report. Quintessence Int. 1991;22:871–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramer M, Marrone J, Stahl B, Burakoff R. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: Identification, treatment, control. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:493–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tipton DA, Howell KJ, Dabbous MK. Increased proliferation, collagen, and fibronectin production by hereditary gingival fibromatosis fibroblasts. J Periodontol. 1997;68:524–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.6.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunhan O, Gardner DG, Bostanic H, Gunhan M. Familial gingival fibromatosis with unusual histologic findings. J Periodontol. 1995;66:1008–11. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.11.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flemming TF. Periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:32–8. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papapanous PN. Risk assessment in the diagnosis and treatment of periodontal disease. J Dent Educ. 1998;62:822–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danesh-Meyer MJ, Holborow DW. Familial gingival fibromatosis: A report of two patients. N Z Dent J. 1993;89:119–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singer SL, Goldblatt J, Hallam LA, Winters JC. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis with recessive mode of inheritance: Case reports. Aust Dent J. 1993;38:427–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1993.tb04755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaturvedi R. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis: A case report. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75:291–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casavecchia P, Uzel MI, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Dibart S, Hart TC, et al. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis: A case report. J Periodontol. 2004;75:770–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.5.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shirasuna K, Okura M, Watatani K, Hayashido Y, Saka M, Matsuya T. Abnormal cellular property of fibroblasts from congenital gingival fibromatosis. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17:381–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1988.tb01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coletta RD, Reynolds MA, Martelli-Junior H, Graner E, Almeida OP, Sauk JJ. Testosterone stimulates proliferation and inhibits interleukin-6 production of normal and hereditary gingival fibromatosis fibroblasts. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2002;17:186–92. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2002.170309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coletta RD, Almeida OP, Reynolds MA, Sauk JJ. Alteration in expression of MMP-1 and MMP-2 but not TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 in hereditary gingival fibromatosis is mediated by TGF-beta 1 autocrine stimulation. J Periodontal Res. 1999;34:457–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim Y, Ratziu V, Choi SG, Lalazar A, Theiss G, Dang Q, et al. Transcriptional activation of transforming growth factor beta 1 and its receptors by the Kruppel-like factor Zf 9/core promoter-binding protein and Sp 1: Potential mechanisms for autocrine fibrogenesis in response to injury. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33750–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kharbanda P, Sidhu SS, Panda SK, Deshmukh R. Gingival fibromatosis: Study of three generations with consanguinity. Quintessence Int. 1993;24:161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cuestas-Carnero R, Bornancini CA. Hereditary generalized gingival fibromatosis associated with hypertrichosis: Report of five cases in one family. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:415–20. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelekis-Cholakis A, Wiltshire WA, Birek C. Treatment and long-term follow-up of a patient with hereditary gingival fibromatosis: A case report. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:290–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emerson TG. Hereditary gingival hyperplasia: A family pedigree of four generations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;19:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]