Abstract

Objectives:

In this study we examine whether adolescents treated for HIV/AIDS in southern Africa can achieve similar treatment outcomes to adults.

Design:

We have used a retrospective cohort study design to compare outcomes for adolescents and adults commencing antiretroviral therapy (ART) between 2004 and 2010 in a public sector hospital clinic in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

Methods:

Cox proportional hazards modelling was used to investigate risk factors for death and loss to follow-up (LTFU) (defined as missing a scheduled appointment by ≥3months).

Results:

One thousand, seven hundred and seventy-six adolescents commenced ART, 94% having had no previous history of ART. The median age at ART initiation was 13.3 years. HIV diagnosis in 97% of adolescents occurred after presentation with clinical disease and a higher proportion had advanced HIV disease at presentation compared with adults [WHO Stage 3/4 disease (79.3 versus 65.2%, P < 0.001)]. Despite this, adolescents had no worse mortality than adults, assuming 50% mortality among those LTFU (6.4 versus 7.3 per 100 person-years, P = 0.75) with rates of loss to follow-up significantly lower than in adults (4.8 versus 9.2 per 100 person-years, P < 0.001). Among those who were followed for 5 years or more, 5.8% of adolescents switched to a second-line regimen as a result of treatment failure, compared with 2.1% of adults (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

With adolescent-focused services, it is feasible to achieve good outcomes for adolescents in large-scale ART programs in sub-Saharan Africa. However, adolescents are at high risk of treatment failure, which compromises future drug options. Interventions to address poor adherence in adolescence should be prioritized.

Keywords: adolescent, adolescent friendly services, AIDS, antiretroviral, antiretroviral therapy, cohort study, HIV, Zimbabwe

Introduction

Over the past decade, southern Africa has seen a marked decline in antenatal HIV prevalence, and also in mother-to-child HIV transmission (MTCT) rates as a result of effective preventive interventions [1,2]. Increasing numbers of HIV-infected children are now surviving to adolescence and beyond because of antiretroviral therapy (ART). In addition, about a third of HIV-infected infants have slow-progressing disease, and substantial numbers of infants infected at the peak of the HIV epidemic in the 1990s are presenting to clinical services for the first time in adolescence [3]. The age-profile of the paediatric epidemic is, thus, changing, and over coming years adolescents are likely to contribute a bigger proportion accessing HIV care than younger children [2].

The continuing scale-up of interventions to prevent MTCT promises further declines in MTCT rates but will not impact upon the existing maturing cohort of HIV-infected children [4]. Paediatric HIV programs in Africa have, however, focused mainly on infants and younger children to date, and relatively little attention has been paid to adolescents. Adolescence is a period of profound physical, cognitive and psychological development; adolescents confront many sociocultural changes and risk-taking behaviours generally become more prevalent [5]. These factors place considerable challenges on adolescents and chronic disease management can worsen during this period [5]. Whether such factors may prevent adolescents achieving good clinical outcomes on ART in Africa is uncertain due to the sparse evidence base [4,6–8]. ART adherence among adolescents has been shown to be poor particularly among those with high-risk behaviours, and virological outcomes among HIV-infected adolescents have been shown to be worse than those in adults [9–12].

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to investigate loss to follow-up (LTFU) and mortality among adolescents in a large public sector HIV treatment programme in Zimbabwe, and compared treatment outcomes to those among adults treated in the same facility.

Methods

Study setting

Patients were drawn from the Mpilo Hospital HIV Clinic in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe's second largest city. Mpilo clinic has provided ART since April 2004, with decentralization of care of adult patients stable on ART to primary care level from 2006, and has accumulated a large cohort of adolescent patients. HIV care at Mpilo is provided by the public sector in partnership with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and other organizations. Although ART initiation was carried out by doctors, routine clinical care was provided mainly by nurses trained in HIV management, with supervision from on-site doctors.

From 2007, additional services for adolescents were introduced, following group discussions with adolescents to identify their needs, and workshops to address stigmatizing behaviours among staff. Adolescents were engaged in service planning decisions through nominated peer representatives. Adolescent-specific activities included peer and non-peer counselling, and a youth club. Activities were designed to promote resilience among adolescents and focused not only on medical issues such as promoting adherence, but on the particular social challenges faced by HIV-positive adolescents, such as bullying and stigma. Participation was promoted by including social activities. Although both adult and adolescent defaulters were actively traced, the adolescent tracing programme was better resourced and integrated into community structures. For additional information on adolescent services see Appendix I.

Inclusion criteria

Study participants were adolescents and adults who initiated ART at Mpilo ART clinic between April 2004 and November 2010. Adolescents were defined as those aged 10 and less than 19 years at time of initiation of ART. Longitudinal patient data were analysed from time of first clinic visit to most recent follow-up before December 2010. Data was not available for patients following decentralization. Treatment was provided in accordance with Zimbabwean National Guidelines, with individuals eligible for ART if they had a CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/μl and/or WHO stage III or IV HIV disease. CD4+ cell count tests were performed free of charge, although availability was limited during 2007 and 2008. Viral load testing was not available.

Data collection

At each clinic visit, comprehensive data including drug regimen, disease stage, incident AIDS-related illness, adverse drug reactions, weight, height for adolescents, laboratory results as well as the individual's next scheduled visit, were routinely recorded using FUCHIA software (Epicentre, Paris, France). Drug regimen information was cross checked against pharmacy data for accuracy. Mortality data were obtained through on-going systematic patient follow-up activities, notification by family and through death register review.

Data analysis

Relevant demographic and clinical information were extracted from FUCHIA and analysed using STATA (version 10; Stata-Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). Comparison of means and proportions was done using the two-tailed t-test and χ2 tests, respectively. For nonparametric data the Mann–Whitney U test was used. Cox proportional hazards modelling was used to investigate risk factors for mortality and LTFU, with variables significant at the P < 0.2 level in univariate analyses being included in the multivariate model. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using log plots. Z-scores for adolescent anthropometric data were derived using WHO standards [13]. CD4+ cell counts were considered current if they were measured within 3 months of the time point of interest.

The potential impact of unrecorded deaths among those lost to follow-up on mortality was investigated by performing a sensitivity analysis, using 30, 50 and 70% probability of death among those who were LTFU. These probabilities were obtained from the estimates of mortality among those defaulting from ART programs reported in a previous meta-analysis [14].

Definitions

Patients were considered LTFU if they were at least 3 months overdue a scheduled visit, with date of LTFU calculated as the mid-point between last attended appointment and the subsequent appointment missed. Records of patients LTFU were continually updated and in the event that an individual returned to the clinic their status was amended and they would continue to contribute person time in the analysis. Patients whose routine HIV care was decentralized to primary care services or transferred to an HIV centre outside Bulawayo were considered to have transferred out of the programme.

Treatment failure was defined as a new or recurrent WHO stage IV condition or a fall to pretherapy CD4+ cell count or 50% drop in CD4+ cell count from the peak value or a CD4+ cell count persistently below 100 cells/μl after 6 months of treatment, as per WHO 2006 recommendations [15].

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Mpilo Hospital Ethical Review Board. Individual consent from patients to use clinical data was not obtained. No personal identification information was collected and records were anonymized to maintain patient confidentiality.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Between April 2004 and November 2010, 13 746 individuals commenced ART (children, adolescents and adults); after exclusion of 28 records due to missing data, we extracted information on 9360 adults and 1776 (13% of cohort) adolescents. The increase in numbers starting ART was highest for adolescents, increasing seven-fold over the study period. As observed in other HIV care programmes, the majority of adults commencing ART were women, with men tending to present with more advanced disease compared with women (WHO stage III/IV disease: 72.7 versus 61.8%, P < 0.001; CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/μl: 74 versus 61% P < 0.001 in males versus females, respectively). This difference was not observed among adolescents (WHO Stage III/IV disease 81 versus 78%, P = 0.065 and CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/μl 51 versus 53%, P = 0.38, in males versus females, respectively).

The median age at ART initiation among adolescents, more than 95% of whom were vertically infected, was 13.3 years and 94% had no history of previous ART use. Only 2.6% of ART-naive adolescents entered the programme via freestanding voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) services compared to 18.3% of adults (P < 0.001), the remainder being diagnosed after presentation with an HIV-related illness. At ART initiation, adolescents had significantly more advanced disease and lower haemoglobin levels, but paradoxically had higher CD4+ cell counts (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristics | N (%) of patients | P | ||

| Total n = 11 136 | Adults n = 9360 | Adolescents n = 1776 | ||

| Demographic | ||||

| Male | 3726 (33.4%) | 2876 (30.7%) | 850 (47.8%) | <0.001 |

| Median age (IQR) (years) | 34.7 (26.7–42.1) | 36.8 (31.1–44.0) | 13.3 (11.4–15.3) | – |

| Clinical | ||||

| Referral from VCT/self-referrala | 1679 (15.1%); (1679/11 108) | 1630 (17.5%); (1630/9334) | 49 (2.8%); (49/1774) | <0.001 |

| History of previous ART use | 15.7% (1747/11 136) | 17.6% (1644/9360) | 5.8% (103/1776) | <0.001 |

| WHO Stage III/IV | 67.3% (6963/10 343) | 65.2% (5727/8784) | 79.3% (1236/1559) | <0.001 |

| Median height for age z score (IQR) | – | – | −2.5 (−3.4 to −1.6); (n = 485) | – |

| Median BMI for age z score (IQR) | – | – | −1.6 (−2.6 to −0.68); (n = 485) | – |

| Median (IQR) CD4+ cell count at ART initiation (cells/μl) | 149 (75–222); (n = 4221) | 144 (75–211); (n = 3441) | 183 (78–289); (n = 780) | <0.001 |

| CD4+ cell count <200 cells/μl at ART initiation | 2856 (67.7%); (n = 4221) | 2429 (70.6%); (n = 3441) | 427 (54.7%); (n = 780) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary TB | 585 (5.2%) | 494 (5.3%) | 89 (5.0%) | 0.633 |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range; VCT, voluntary counselling and testing. Numbers of participants for whom data was available indicated in parentheses.

aRemainder diagnosed following HIV-indicator illness.

Treatment outcomes are derived from a total of 22 127 person-years of follow-up, of which 3478 person-years were contributed by adolescents. The median duration on treatment was 567 (interquartile range 223–1082) days for adolescents and 490 (191–947) days for adults.

Outcomes following antiretroviral therapy initiation

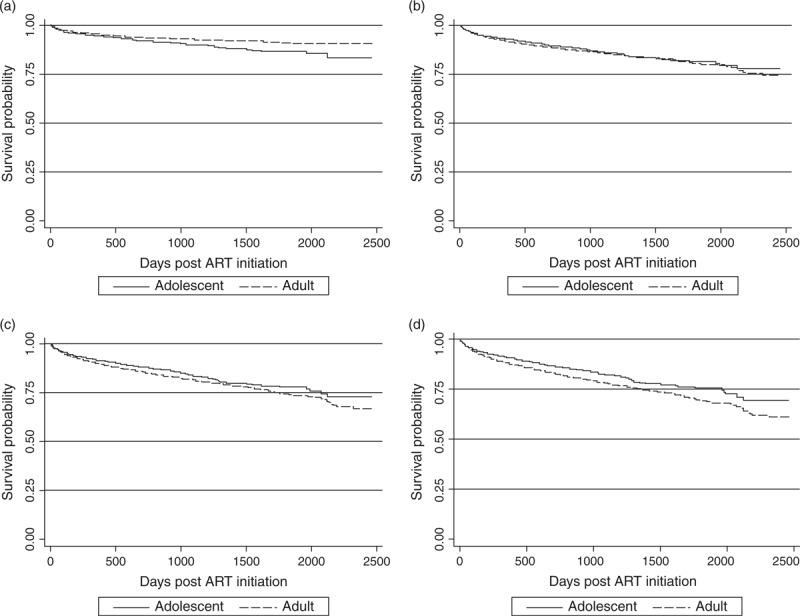

The rate of LTFU was approximately twice as high in adults when compared with adolescents at each follow-up interval (9.2/100 versus 4.8/100 person-years; hazard ratio = 1.9, P < 0.001). The rate of recorded deaths was higher in adolescents than in adults (log rank test P < 0.001). However, when adjusted for likely mortality rates (30–70%) among those lost to follow-up, there was no difference in mortality between the two groups (Fig. 1). As in other HIV programs, rates of death and LTFU were highest in the first 6 months following initiation of ART in both groups, and CD4+ cell count gains were largest in the first 12 months of treatment. Importantly, the proportion of adolescents under follow-up who switched to a second line regimen during the study period was nearly three times that observed in adults (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Survival among adults and adolescents commencing ART between 2004 and 2010, given different probabilities of death among those lost to follow-up (LTFU).

(a) Unadjusted mortality (b) 30% LTFU assumed to have died (c) 50% LTFU assumed to have died (d) 70% LTFU assumed to have died.

Table 2. Treatment outcomes at 6, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 months for adults and adolescents commencing ART between April 2004 and November 2010.

| Outcomes N (%) | At 6 months | At 12 months | At 24 months | At 36 months | At 48 months | At 60 months |

| Adults (N = 9360) | ||||||

| Known deaths (%) | 279 (3.0%) | 363 (3.9%) | 458 (4.9%) | 487 (5.2%) | 505 (5.4%) | 512 (5.5%) |

| Lost to follow-up (%) | 663 (7.1%) | 994 (10.1%) | 1284 (13.7%) | 1448 (15.9%) | 1604 (17.1%) | 1664 (17.7%) |

| Decentralized/moved out of area (%)a | 8 (0.1%) | 22 (0.2%) | 213 (2.3%) | 874 (9.3%) | 1388 (14.8%) | 1660 (17.7%) |

| Still actively followed (%) | 8667 (92.4%) | 8365 (89.2%) | 7360 (78.5%) | 6468 (68.9%) | 5813 (62.0%) | 5475 (58.4%) |

| Switched to second-line regimen (%)b | 28 (0.3%) | 42 (0.5%) | 62 (0.8) | 78 (1.2%) | 97 (1.7%) | 116 (2.1%) |

| CD4+ cell count >200 cells/μl (%)c | 757 (55.8%) | 314 (67.0%) | 86 (72.3%) | 25 (78.1%) | 6 (60%); | 8 (80%); |

| (n = 1356) | (n = 469) | (n = 119) | (n = 32) | (n = 10) | (n = 10) | |

| Median CD4+ cell count (IQR)c | 219 (142–313) | 255 (171–359) | 282 (196–376) | 312 (229–544) | 277 (173–699) | 396 (234–469) |

| Adolescents (N = 1776) | ||||||

| Known deaths (%) | 68 (3.8%) | 84 (4.7%) | 109 (6.1%) | 121 (6.8%) | 130 (7.3%) | 133 (7.4%) |

| Lost to follow-up (%) | 63 (3.5%) | 88 (4.9%) | 124 (6.0%) | 147 (8.2%) | 160 (9.0%) | 164 (9.2%) |

| Decentralized/moved out of area (%)a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.2%) | 6 (0.3%) | 8 (0.4%) |

| Still actively followed (%) | 1641 (92.0%) | 1597 (89.6%) | 1533 (86.0%) | 1495 (83.8%) | 1468 (82.3%) | 1458 (81.8%) |

| Switched to second-line regimen (%)b | 4 (0.2%) | 7 (0.4%) | 16 (1.0%) | 34 (2.3%) | 59 (4.0%) | 84 (5.8%) |

| CD4+ cell count >200 cells/μl (%)c | 294 (83%) | 236 (93%) | 124 (91%) | 91 (89%) | 53 (78%) | 22 (75.9%) |

| (n = 354) | (n = 254) | (n = 137) | (n = 102) | (n = 68) | (n = 29) | |

| Median CD4+ cell count (IQR)c | 411 (261–620) | 504 (355–733) | 578 (384–831) | 603 (400–789) | 395 (207–604) | 361 (237–657) |

IQR, interquartile range.

aAfter transfer out of programme or decentralization, no further update of outcomes occurred.

bAmong individuals under active follow-up at time point of interest.

cFor those with a CD4+ test result within 3 months of the time point of interest.

Risk factors for death and loss to follow-up

Haemoglobin less than 11 g/dl, CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/μl and BMI z score less than −2 at initiation were associated with an increased risk of death among adolescents, although only haemoglobin remained significantly associated with risk of death on multivariate analysis (Table 3). Among adults, sex, age, CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/μl, haemoglobin less than 11 g/dl, WHO stage III/IV, BMI less than 18 kg/m2 and later year of initiation were all associated with risk of death on univariate analysis. Haemoglobin and year of initiation remained associated with death on multivariate analysis, as did CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/μl, which was the strongest independent-risk factor, hazard ratio = 8.4, P = 0.037 (Table 3). Among adults, male sex and later years of ART initiation were independently associated with risk of LTFU. These associations were not observed for adolescents (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors at initiation of antiretroviral therapy associated with risk of death and lost to follow-up in adolescents and adults.

| Adolescents | Adults | |||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | P | HR | P | HR | P | HR | P | |

| Risk factors for death | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| Female | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.25 | 2.6 (0.9–7.7) | 0.08 | 0.62 (0.5–0.7) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.46–2.0) | 0.62 |

| One year increase in age at initiation | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.10 | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 0.15 | 1.02 (1.0–1.0) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.96–1.0) | 0.88 |

| CD4+ cell count (cells/μl) | ||||||||

| CD4+ ≥200 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| CD4+ <200 | 2.9 (1.5–5.5) | 0.001 | 2.8 (0.8–10.0) | 0.11 | 3.8 (2.3–6.4) | <0.001 | 8.4 (1.1–61.9) | 0.04 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | ||||||||

| Hb>11 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| Hb < 11 | 2.7 (1.2–6.4) | 0.02 | 3.2 (1.0–9.6) | 0.04 | 3.1 (1.9–4.9) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 0.04 |

| Pulmonary TB | ||||||||

| No | 1.0 | – | – | – | 1.0 | – | – | – |

| Yes | 1.1 (0.5–2.3) | 0.84 | – | – | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 0.61 | – | – |

| WHO disease staging | ||||||||

| I/II | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| III/IV | 1.6 (1.0–2.9) | 0.06 | 0.96 (0.2–3.7) | 0.95 | 2.4 (1.9–3.0) | <0.001 | 1.8 (0.8–3.8) | 0.16 |

| Anthropometric scoresa | ||||||||

| BMI z score ≥−2/≥18 kg/m2 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| BMI z score <−2/<18 kg/m2 | 1 8 (0.5–6.8) | 0.013 | 0.65 (0.22–1.9) | 0.44 | 3.6 (2.6–5.1) | <0.001 | 1.7 (0.9–3.4) | 0.11 |

| Height age z score ≥−2 | 1.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Height age z score <−2 | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 0.22 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Per 1 year increase in year of initiation | 0.83 (0.7–0.9) | 0.001 | 0.97 (0.7 –1.4) | 0.86 | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | <0.001 | 0.7 (0.52–0.98) | 0.04 |

| Risk factors for LTFU | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| Female | 1.16 (0.9–1.6) | 0.34 | 1.0 (0.66–1.61) | 0.90 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.78 | 0.64 (0.43–0.93) | 0.02 |

| One year increase in age at initiation | 1.24 (1.2–1.3) | 0.001 | 1.2 (1.11–1.34) | 0.001 | 1.0 | 0.16 | 1.0 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 |

| CD4+ cell count (cells/μl) | ||||||||

| CD4+ ≥200 | 1.0 | – | – | – | 1.0 | – | – | – |

| CD4+ under 200 | 1.34 (0.8–2.2) | 0.24 | – | – | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.78 | – | – |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | ||||||||

| Hb ≥11 | 1.0 | – | – | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| Hb <11 | 1.25 (0.7–2.4) | 0.48 | – | – | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 0.01 | 1.16 (0.81–1.65) | 0.40 |

| Pulmonary TB | ||||||||

| No | 1.0 | – | – | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| Yes | 1.48 (0.8–2.7) | 0.21 | – | – | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | <0.001 | 1.23 (0.54–2.85) | 0.62 |

| WHO disease staging | ||||||||

| I/II | 1.0 | – | – | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| III/IV | 0.8 (0.54–1.19) | 0.28 | – | – | 1.2 (1.04–1.29) | 0.006 | 1.23 (0.86–1.78) | 0.26 |

| Anthropometric scoresa | ||||||||

| BMI z score ≥−2/≥18 kg/m2 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| BMI z score <−2/<18 kg/m2 | 1 33 (0.9–2.0) | 0.20 | 1.12 (0.72–1.77) | 0.60 | 1.58 (1.4–1.8) | <0.001 | 1.05 (0.70–1.60) | 0.81 |

| Height age z score ≥−2 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Height age z score <−2 | 0.93 (0.6–1.5) | 0.76 | 0.98 (0.60–1.60) | 0.94 | – | – | – | – |

| Per 1 year increase in year of initiation | 1.17 (1.1–1.3) | 0.005 | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 0.89 | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.03–1.36) | 0.02 |

HR, hazard ratio. Risk factors significant at the P = 0.2 level were included in the multivariate model. Sex and age were included in multivariate model a-priori.

aBMI categorized as z score at least −2 or less than −2 in adolescents; BMI categorized as at least 18 kg/m2 or less than 18 kg/m2 in adults. Height not recorded in adults.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was the high retention rates and low mortality rates among adolescents enrolled in a public sector HIV care service. Although there are few direct data for adolescents in HIV programs, what evidence there is has generally shown worse treatment outcomes among adolescents than among adults [7,9,11,16,17]. The rates of retention in care for adolescents in this large cohort exceed those previously documented for this age-group in other African HIV care programs [7,8,18], and are considerably higher than the range of 70–77% for programme retention at 24 months reported in a systematic review of HIV treatment outcomes by Fox and Rosen [19].

The high rate of retention in care among adolescents that was observed in this cohort is remarkable because this group faces considerable barriers to accessing and remaining in HIV care [20]. Current HIV diagnosis and care services are mainly aimed at adults, infants and young children and local perceptions often tend to exclude HIV-infected adolescents, many of whom are orphans. Transition from paediatric to adult services may also increase the risk of interruption in care. The number of adolescents who initiated ART increased seven-fold over the study period, compared with a two-fold increase in the numbers of adults. By the end of the study period 23% of all actively followed patients were adolescents, a far higher proportion than seen in facilities elsewhere in the country (Data from Ministry of Health and Child Welfare, Zimbabwe). This finding, previously noted [3], is likely to reflect the success of adolescent friendly services in improving access and retention in care.

Only a minority of adolescents were tested through VCT services. VCT services largely neglect adolescents and provider-initiated testing and counselling in health facilities is not routinely offered to this age group. The legal requirement for guardian consent for HIV testing of a person aged under 16 years in Zimbabwe may also be a barrier to testing, especially as many children may have no guardian or experience changing guardianship [21,22]. The majority of adolescents were diagnosed with HIV following presentation with a clinical illness. Interestingly, while the proportion of adolescents presenting with advanced disease stage was significantly higher than in adults, adolescents had higher baseline CD4+ cell counts than did adults as well as better immune reconstitution at 12 months following ART initiation. Although adolescent mortality rates were no higher than those in adults, with earlier identification and treatment, adolescents would be expected to achieve even better treatment outcomes. The discrepancy between disease stage and CD4+ cell count in this age-group has been noted in other studies, and may be due to a poor ‘quality’ of immune response despite preserved counts. A potential important implication is that CD4+ cell count may not be an appropriate criterion for starting ART in older children [12,17].

As expected, markers of advanced disease such as anaemia, low CD4+ cell count and low BMI were associated with an increased risk of death. The lack of observed association between tuberculosis (TB) at initiation and mortality contrasts other findings [23], and may be a result of underreporting of (TB), furthermore, TB was managed at a separate site, where national guidelines at the time advised late initiation, a practice now discouraged by WHO [23]. Some coinfected individuals are, therefore, likely to have died prior to initiation, outside of Mpilo hospital and the association between TB and LTFU may reflect additional unrecorded deaths. The association between male sex and risk of LTFU among adults has been documented in other studies, and likely reflects the poor health-seeking behaviour among men [24,25]. Increasing LTFU with increasing programme years may highlight the increasing challenge of following up patients in large and/or expanding programmes.

A concerning finding was that use of second-line ART regimen due to treatment failure was significantly higher in adolescents than in adults despite adults being more treatment-experienced than adolescents, and also exceeded the national average use of second-line ART [26]. This is likely to reflect poorer underlying adherence, and is consistent with other studies that show that adolescents have a disproportionately high risk of poor adherence to ART [7,9–11,27,28]. Adherence to treatment has also been shown to worsen during adolescence in other chronic diseases [5]. Potential risk factors for nonadherence in adolescents include delayed disclosure of HIV status, the need to conform with peers, experienced or anticipated stigma, and difficulty managing treatment while schooling especially if attending boarding school [21,29,30]. Suboptimal care giving is another potential factor as treatment outcomes for chronic childhood illnesses are greatly influenced by guardians’ awareness and willingness to invest time and effort into accessing care [31]. HIV-infected children may be at especially high risk of subtle forms of neglect because of maternal illness, as guardians tend to invest less in unhealthy children who are adopted or maternal orphans [32]. Poor adherence not only leads to treatment failure in a setting where treatment options are limited but also leads to risk of onward horizontal transmission of drug-resistant strains.

This study reports on a large cohort of HIV-infected adolescents treated in a single centre in sub-Saharan Africa. The large numbers, long duration of follow-up and availability of detailed individual-level data which was systematically entered into an electronic database are major strengths. Furthermore, this study reports from a cohort managed in a public sector clinic, and therefore the findings are likely to be more generalizable than data from cohorts enrolled in research studies including clinical trials.

The study is subject to all the limitations of a retrospective cohort study design, such as incomplete data. Anthropometric measures were less comprehensively recorded than other variables. Omissions in assessment and underrecording in patient notes are likely causes. CD4+ cell count measurements were not regularly carried out because of logistical reasons. CD4+ results at initiation were only available for 44% of adolescents and 37% of adults. However, outcomes did not differ between those who had and who did not have CD4+ cell counts at initiation (Appendix 2). Common to studies of this type, ascertainment of reasons for LTFU was incomplete. Patients rarely notified the clinic when relocating to another region or country for personal reasons and some of those recorded, as LTFU will have moved to other areas where they may or not be receiving treatment. A proportion of adults and adolescents who were lost to follow-up are likely to have died. We have however attempted to account for this by carrying out a sensitivity analysis to assess how likely rates of death among those LTFU would impact mortality rates in our cohort [14,33]. Data on adherence was not available and HIV viral load testing was not available to confirm treatment failure. Given that treatment failure was diagnosed using clinical and immunological criteria, which have poor accuracy, particularly among children, the actual numbers who failed treatment are likely to have been higher in both groups.

Follow-up data were not available for patients whose care was decentralised. The impact of this on overall outcomes is likely to be insignificant as decentralization generally occurred after 2 years on ART while most of the LTFU and mortality was highest in the first 6 months of commencing ART, with relatively modest increases in mortality and LTFU seen after 24 months on ART.

Children have been a priority target for primary HIV prevention efforts in Africa for many years now, but relatively little attention has been paid to the complex health needs of HIV-infected adolescents [34]. Our results show that by developing dedicated adolescent friendly services and by involving adolescents in their own management, many of the inherent challenges of keeping young people in care may be overcome. However, effective strategies to address the poor adherence in this age group are needed to further improve treatment outcomes. In addition, there is an urgent need to address barriers to access to HIV testing and to develop HIV-testing facilities targeted towards adolescents.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the MoHCW and the MSF staff, and patients at Mpilo ART clinic Bulawayo. We would like to thank Miriam Siziba for her work with the adolescent counselling service and Pilar Perez-Vico for assistance with the literature search for this manuscript. We also acknowledge the Million Memory Project Bulawayo, Contact Counselling Services Bulawayo and the Baylor Adolescent Centre, Gaborone, Botswana, for assistance with developing Adolescent specific services.

Role of study authors: A.S. and R.A.F. designed the study. A.S. conducted the analysis which was reviewed by R.A.F. A.S., H.G., M.D., M.N., W.N., J.F.S., F.T. and R.A.F. contributed to interpretation of study findings. All authors contributed to writing the study manuscript.

This study was funded by MSF Operational Centre Barcelona Athens. Co-authors were not funded to contribute and their salaries came from their host institutions.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Correspondence to Dr Amir Shroufi, Médecins Sans Frontières, 3 Natal Road, Belgravia, Harare, Zimbabwe. E-mail: amir.shroufi@doctors.org.uk

References

- 1.Halperin DT, Mugurungi O, Hallett TB, Muchini B, Campbell B, Magure T, et al. A surprising prevention success: why did the HIV epidemic decline in Zimbabwe?. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrand RA, Corbett EL, Wood R, Hargrove J, Ndhlovu CE, Cowan FM, et al. AIDS among older children and adolescents in Southern Africa: projecting the time course and magnitude of the epidemic. AIDS 2009; 23:2039–2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrand R, Lowe S, Whande B, Munaiwa L, Langhaug L, Cowan F, et al. Survey of children accessing HIV services in a high prevalence setting: time for adolescents to count?. Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88:428–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation 2 WHO antiretroviral therapy of HIV in infants and children in resource limited settings, toward universal access. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawyer SM, Drew S, Yeo MS, Britto MT. Adolescents with a chronic condition: challenges living, challenges treating. Lancet 2007; 369:1481–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowitz M, Saag M, Powderly WG, Hurley AM, Hsu A, Valdes JM, et al. A preliminary study of ritonavir, an inhibitor of HIV-1 protease, to treat HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:1534–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Nguyen H, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, virologic and immunologic outcomes in adolescents compared with adults in southern Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 51:65–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakanda C, Birungi J, Mwesigwa R, Nachega JB, Chan K, Palmer A, et al. Survival of HIV-infected adolescents on antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: findings from a nationally representative cohort in Uganda. PloS One 2011; 6:e19261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy DA, Belzer M, Durako SJ, Sarr M, Wilson CM, Muenz LR, et al. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence among adolescents infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005; 159:764–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belzer ME, Fuchs DN, Luftman GS, Tucker DJ. Antiretroviral adherence issues among HIV-positive adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health 1999; 25:316–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy DA, Wilson CM, Durako SJ, Muenz LR, Belzer M. Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network. Antiretroviral medication adherence among the REACH HIV-infected adolescent cohort in the USA. AIDS Care 2001; 13:27–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn PM, Rudy BJ, Lindsey JC, Douglas SD, Lathey J, Spector SA, et al. Long-term observation of adolescents initiating HAART therapy: three-year follow-up. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2007; 23:1208–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organisation WHO Anthos (version 3.2.2.) and Macros [Internet]. 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/publications/en/ [Accessed 5 April 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinkhof MWG, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2009; 4:e5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organisation Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. Recommendations for a public health approach (2006 revision). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekouevi DK, Balestre E, Ba-Gomis FO, Eholie SP, Maiga M, Amani-Bosse C, et al. Low retention of HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in 11 clinical centres in West Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2010; 15 (Suppl 1):34–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nglazi MD, Lawn SD, Kaplan R, Kranzer K, Orrell C, Wood R, et al. Changes in programmatic outcomes during 7 years of scale-up at a community-based antiretroviral treatment service in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 56:e1–e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nglazi MD, Kranzer K, Holele P, Kaplan R, Mark D, Jaspan H, et al. Treatment outcomes in HIV-infected adolescents attending a community-based antiretroviral therapy clinic in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis 2012; 12:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2010; 15 (Suppl 1):1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrand RA, Bandason T, Musvaire P, Larke N, Nathoo K, Mujuru H, et al. Causes of acute hospitalization in adolescence: burden and spectrum of HIV-related morbidity in a country with an early-onset and severe HIV epidemic: a prospective survey. PLoS Med 2010; 7:e1000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feucht UD, Kinzer M, Kruger M. Reasons for delay in initiation of antiretroviral therapy in a population of HIV-infected South African children. J Trop Pediatr 2007; 53:398–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilfert C, Aronson JE, Beck DT, Fleischman AR, Kline MW, Mofenson LM, et al. Planning for children whose parents are dying of HIV/AIDS. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Pediatric AIDS, 1998–1999. Pediatrics 1999; 103:509–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blanc FX, Sok T, Laureillard D, Borand L, Rekacewicz C, Nerrienet E, et al. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1471–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braitstein P, Boulle A, Nash D, Brinkhof MWG, Dabis F, Laurent C, et al. Gender and the use of antiretroviral treatment in resource-constrained settings: findings from a multicenter collaboration. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008; 17:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen SCC, Yu JKL, Harries AD, Bong CN, Kolola-Dzimadzi R, Tok TS, et al. Increased mortality of male adults with AIDS related to poor compliance to antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Trop Med Int Health 2008; 13:513–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logistics Management Information Systems. Zimbabwean Ministry of Health and Child Welfare. Request, submitted to AIDS and TB Unit, MoHCW Zimbabwe, by MSF on 2 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohn SE, Jiang H, McCutchan JA, Koletar SL, Murphy RL, Robertson KR, et al. Association of ongoing drug and alcohol use with nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy and higher risk of AIDS and death: results from ACTG 362. AIDS Care 2011; 23:775–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy DA, Sarr M, Durako SJ, Moscicki AB, Wilson CM, Muenz LR, et al. Barriers to HAART adherence among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003; 157:249–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchanan AL, Montepiedra G, Sirois PA, Kammerer B, Garvie PA, Storm DS, et al. Barriers to medication adherence in HIV-infected children and youth based on self- and caregiver report. Pediatrics 2012; 129:e1244–e1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandwani S, Koenig LJ, Sill AM, Abramowitz S, Conner LC, D’Angelo L. Predictors of antiretroviral medication adherence among a diverse cohort of adolescents with HIV. J Adolesc Health 2012; 51:242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messer LC, Pence BW, Whetten K, Whetten R, Thielman N, O’Donnell K, et al. Prevalence and predictors of HIV-related stigma among institutional- and community-based caregivers of orphans and vulnerable children living in five less-wealthy countries. BMC Public Health 2010; 10:504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang M, Dunbar M, Laver S, Padian N. Maternal versus paternal orphans and HIV/STI risk among adolescent girls in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 2008; 20:214–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brinkhof MWG, Spycher BD, Yiannoutsos C, Weigel R, Wood R, Messou E, et al. Adjusting mortality for loss to follow-up: analysis of five ART programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. PloS One 2010; 5:e14149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray GE. Adolescent HIV: cause for concern in Southern Africa. PLoS Med 2010; 7:e1000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.