Abstract

Introduction: We have recently shown that in high cholesterol-fed rabbits, the sensitivity of epicardial adipose tissue to changes in dietary fat is higher than that of subcutaneous adipose tissue. Although the effects of diabetes on epicardial adipose tissue thickness have been studied, the influence of diabetes on profile of epicardial free fatty acids (FFAs) has not been studied. The aim of this study is to investigate the effect of diabetes on the FFAs composition in serum and in the subcutaneous and epicardial adipose tissues in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). Methods: Forty non-diabetic and twenty eight diabetic patients candidate for CABG with >75% stenosis participated in this study. Fasting blood sugar (FBS) and lipid profiles were assayed by auto analyzer. Phospholipids and non-estrified FFA of serum and the fatty acids profile of epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissues were determined using gas chromatography method. Results: In the phospholipid fraction of diabetic patients’ serum, the percentage of 16:0, 18:3n-9, 18:2n-6 and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) was lower than the corresponding values of the non-diabetics; whereas, 18:0 value was higher. A 100% increase in the amount of 18:0 and 35% decrease in the level of 18:1n-11 was observed in the diabetic patients’ subcutaneous adipose tissue. In epicardial adipose tissue, the increase of 18:0 and conjugated linolenic acid (CLA) and decrease of 18:1n-11, w3 (20:5n-3) and 22:6n-3 were significant; but, the contents of arachidonic acid and its precursor linoleic acid were not affected by diabetes. Conclusion: The fatty acids’ profile of epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissues is not equally affected by diabetes. The significant decrease of 16:0 and w3 fatty acids and increase of trans and conjugated fatty acids in epicardial adipose tissue in the diabetic patients may worsen the formation of atheroma in the related arteries.

Keywords: Fatty Acid Profile, Epicardial Adipose Tissue, Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue, Diabetes, Coronary Artery Bypass Graft

Introduction

It has been reported that intra myocardial arteries are resistant to atherosclerosis.1 Chaowalite et al. have demonstrated that coronary arteries that are not surrounded by epicardial adipose tissue are protected against the onset and progression of atherosclerosis.2 It has also been shown that the risk of atherosclerosis in subcutaneous and mammary arteries is low in comparison with coronary arteries.3 There are significant differences between fatty acids’ profile of coronary and mammary arteries in atherosclerotic patients.4 It seems that the amount and type of fatty acids in adipose tissues play a pivotal role in the onset and development of atherosclerosis.5 According to Koustar and coworkers, plasma free fatty acids (FFAs) can enter into the subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues.6 It has been proved that in healthy and non-obese young people the FFAs’ uptake into the visceral adipose tissue is much more than their uptake into the skin.7 Based on some evidence visceral adipose tissue is metabolically very active and therefore clinically important.8 Epicardial adipose tissue is a part of visceral adipose tissue that is deposited around the heart and epicardial coronary arteries.9 The thickness of epicardial adipose tissue is associated with the incidence and prevalence of cardiovascular disease.10 We have previously reported that epicardial FFAs’ profiles are different from that of subcutaneous adipose tissue in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG).11 In addition, in the high cholesterol-fed rabbits we have recently shown that epicardial adipose tissue is very sensitive to changes in dietary fat than subcutaneous adipose tissue.12

Patients with diabetes type II often have a high serum level of fatty acids.13 Reduction in FFAs’ oxidation and long chain FFAs’ accumulation has been reported in hyperglycemia.14 In spite of the frequent reports on the effect of diabetes or other metabolic diseases on the epicardial adipose tissue thickness15-17 and its role in the coronary artery complications, the effect of diabetes on the profile of epicardial FFAs has not been studied so far. In the present study, the effect of diabetes on the FFAs’ composition in serum and in the subcutaneous and pericardial adipose tissues has been investigated in patients undergoing CABG.

Materials and methods

Materials

Methanol (HPLC grade), chloroform, methanol, benzene (HPLC grade), acetyl chloride, acetic acid, diethyl ether and hexane were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Internal standard powder and standard fatty acid methyl esters were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Company.

Patients

Forty non-diabetic and twenty eight diabetic patients candidate for CABG with >75% stenosis were used in this study. All patients were accepted at Madani hospital in Tabriz. Hypertensive patients were excluded from the study which limited the number of participants. The proposal was approved by Regional Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Patients with high blood cholesterol and hypertension were excluded from the study. The diabetic patients were evaluated and selected according to the WHO criteria.18 The baseline characteristics of the patients have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients without or with diabetes candidate for coronary artery bypass graft .

| Variable | Non-Diabetic (n=40) | Diabetic (n=20) | p-Value |

| Age(Year) | 57.6±6.9 | 53.4±7.6 | 0.102 |

| Weight(kg) | 76.2±11.3 | 71.5±11.2 | 0.1332 |

| Height(cm) | 166.1±8.5 | 160.4±8.6 | 0.0178 |

| BMI(kg/m2 | 27.5±4.4 | 27.7±4.0 | 0.8649 |

| Male:Female | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Smoking(%) | 45 | 48 | 0.8542 |

| FBS(mg/dl) | 92.8±10.6 | 148.0±36.4 | 0.000 |

| Hb A1c(%) | 4.0±0.5 | 5.5±1.1 | 0.032 |

| Cholesterol(mg/dl) | 163.4±38.7 | 195.1±41.0 | 0.001 |

| Triglyceride(mg/dl) | 97.3 ±23.6 | 158.4±36.2 | <0.0001 |

| HDL(mg/dl) | 38.4±9.8 | 36.1±6.8 | 0.3508 |

| LDL(mg/dl) | 101.2±37.9 | 116.0±46.7 | 0.1926 |

Sample collection

Fasted blood sample (5 ml) was collected from each patient before operation; the serum was obtained after centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes and kept at -70°C until use. The subcutaneous and epicardial adipose tissue samples (0.5-1.0 g) were obtained during the surgery. Epicardial adipose tissue biopsies were taken near the proximal right artery, and subcutaneous peripheral adipose tissue samples were obtained from the site of vein harvesting in the leg. Samples were dissolved in hexane and stored at -70°C in glass vials for ≤3 months until analysis.

Measurement of metabolic parameters

Serum FBS, cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL and LDL concentrations were assayed by standard kits (Pars Azemoon) using auto analyzer (Aboat).

Phospholipids and non-estrified FFA extraction from serum

The total lipids were separated from serum based on Bligh & Dyer protocol.19 The phospholipids and non-estrified fatty acids’ (NEFAs) fractions were obtained using thin layer chromatography (TLC) technique. The FFAs of the obtained phospholipid and NEFA fractions were separated as follows:

The fractions obtained from the TLC plate were transferred into a methanol/benzene (1:4) tube containing 50 mg/ml tridecanoic acid (the internal standard). Then, acetyl chloride was added into the tubes and the tubes were kept at boiling water for 60 minutes. To stop the reaction, potassium carbonate 6% was added into the tubes and immediately the tubes were centrifuged at 1,700 rpm for 4 minutes. The FFAs’ content of the supernatants was measured by gas chromatography method.

Fatty acid extraction from adipose tissues

First, hexane was evaporated from the vials containing epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissues using nitrogen gas and the content of epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissues, fatty acids, was determined as described before.20 The isolated fatty acids were converted to the corresponding methylated esters using acetyl chloride and methanol. The reaction mixture was neutralized by the appropriate amount of potassium carbonate and the methylated esters were extracted by hexane and kept at -70°C under nitrogen gas until the analysis.

Gas chromatography analysis

The gas chromatography analysis was carried out by Gas chromatograph (Buck Scientific 610) with 6 m´0.25 mm column (Teknokroma TR-CN100). The oven temperature was set at 170-210°C (1°C/min) at the beginning and then isothermalized for 45 min. The combined inter- and intra-assay of variation was 2.0, 2.8, 18.4 and 11.3% for palmitic acid (16:0), linoleic acid (18:2n-6), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), respectively.

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as mean±SD. The comparison of mean variables between groups was carried out using means-independent simple t-test. The equal or less than 0.05 probabilities were considered as significant. All data analysis was performed using SPSS software.

Results

The demographic information of diabetic and non-diabetic patients who participated in this study has been shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference between two groups regarding age, BMI, height, weight, and smoking. In diabetic and non-diabetic groups, the ratios of men to women were 1.5 to 2, respectively. The blood levels of glucose (p=0.000), glycosilated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (p=0.032), cholesterol (p=0.001) and triglyceride (p=0.000) were significantly high in the diabetic patients. However, the levels of cholesterol, LDL, and HDL were the same in both groups.

The profile of fatty acids in phospholipid and FFA fractions in the serum of studied groups has been summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Fatty acids profile of serum free fatty acid and phospholipid fractions in patients without or with diabetes* .

| Fatty Acids | Non-Diabetic (n=40) |

Diabetic (n=20) | p-Value |

| NEFAF** | |||

| 12:0 (Lauric acid) | 0.68±0.10 | 0.44± 0.09 | 0.038 |

| 16:0 (Palmitic acid) | 28.50± 3.15 | 24.12± 1.22 | 0.011 |

| 20:4 n-6 (Arachidonic acid) | 0.64± 0.19 | 0.39± 0.07 | 0.015 |

| PLF** | |||

| 16:0 (Palmitic acid) | 27.84± 1.82 | 25.01± 1.58 | <0.0001 |

| 18:0 (Stearic acid) | 13.15 ±1.24 | 14.62± 1.18 | <0.0001 |

| 18:1 n-9 (Oleic acid) | 8.13± 1.24 | 8.96 ±1.08 | 0.0135 |

| 18:2 n-6 (Linoleic acid) | 22.95 ±2.64 | 20.25± 2.45 | 0.0003 |

| 18:3 n-9 (Linolenic acid) | 0.16 ±0.04 | 0.11±0.05 | 0.0001 |

| MUFAs** | 11.64 ±1.36 | 9.45± 1.32 | <0.0001 |

*Only those fatty acids that their concentrations in the studied groups were found to be significantly different were included in the table.

**NEFAF: non-esterified fatty acid fraction, PLF: phospholipid fraction, MUFAs: mono-unsaturated fatty acids.

In the FFA fraction of diabetic patients, the percentage of the saturated FFA 12:0 was higher (p=0.038) than that of non-diabetics, whereas that of 16:0 was low (p=0.011). Meanwhile, the percentage of unsaturated fatty acid 20:3 n-9 in this fraction was found to be high (p=0.015) in non-diabetic patients than in diabetic. In contrast to FFA fraction, the fatty acids in the phospholipid fraction were more variable in both groups. In the phospholipid fraction of diabetic patients’ serum, the percentage of 16:0 (p=0.000) and 18:0 (p=0.000) were respectively lower and higher than the corresponding values in the non-diabetics. There was also a significant reduction in the percentage of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) in diabetic patients (p=0.000). The analysis of data indicated that this observation arose from the low level of 18:1n-9(p=0.013). Regarding the polyunsaturated fatty acids’ (PUFAs) status, 18:3n-9 (p=0.000) and 18:2n-6 (p=0.000) percentages in the serum phospholipid fraction of the diabetic patients were lower than those of the non-diabetics.

The content of epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue FFAs has been demonstrated in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3. Fatty acids profile of epicardial adipose tissue in patients with or without diabetes .

| Fatty Acids | Non-Diabetic (n=40) |

Diabetic (n=20) |

p-Value |

| 12:0 (Lauric acid) | 0.97±0.67 | 0.76± 0.36 | 0.373 |

| 14:0 (Myristic acid) | 2.83 ±0.56 | 2.29 ± 0.68 | 0.081 |

| 16:0 (Palmitic acid) | 28.39± 3.15 | 25.42± 2.90 | 0.021 |

| 16:1t (Palmitoleic acid) | 1.32 ±0.26 | 2.04± 0.28 | <0.0001 |

| 16:1n-7 (Palmitoleic acid) | 5.01 ±1.28 | 5.38± 1.85 | 0.843 |

| 18:0 (Stearic acid) | 4.40 ±1.02 | 6.41± 1.08 | 0.003 |

| 18:1 t (Oleic acid) | 4.48± 1.17 | 5.68 ±1.12 | 0.0004 |

| 18:1 n-9 (Oleic acid) | 33.41± 4.61 | 35.10 ±3.70 | 0.757 |

| 18:1n-11 (Oleic acid) | 2.58± 0.76 | 2.32 ±0.35 | 0.000 |

| 18:2 t (Linoleic acid) | 1.28 ±0.22 | 1.42± 0.31 | 0.0480 |

| 18:2 n-6 (Linoleic acid) | 12.16 ±2.07 | 10.25± 1.95 | 0.630 |

| 18:3 n-9 (Linolenic acid) | 0.57± 0.23 | 0.62± 0.24 | 0.058 |

| CLA (Conjugated Linoleic acid) | 1.04± 0.18 | 0.71± 0.22 | 0.033 |

| 20:4 n-6 (Arachidonic acid) | 0.58± 0.15 | 0.60± 0.19 | 0.409 |

| 20:5 n-3 (Eicosapentaenoic acid) | 0.36 ± 0.09 | 0.18± 0.04 | 0.015 |

| 22:6 n-3 (docosahexaenoic acid) | 0.32± 0.11 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.000 |

Table 4. Fatty acids profile of subcutaneous adipose tissue in the patients with or without diabetes .

| Fatty Acids | Non-Diabetic (n=40) |

Diabetic (n=20) |

p-Value |

| 12:0 (Lauric acid) | 0.82±0.21 | 0.87± 0.22 | 0.801 |

| 14:0 (Myristic acid) | 2.48±0.66 | 2.68 ± 0.63 | 0.345 |

| 16:0 (Palmitic acid) | 22.12± 3.71 | 22.70± 4.12 | 0.987 |

| 16:1t (Palmitoleic acid) | 1.41 ±0.32 | 1.45± 0.29 | 0.6398 |

| 16:1n-7 (Palmitoleic acid) | 7.42 ±1.64 | 8.82± 1.56 | 0.033 |

| 18:0 (Stearic acid) | 2.46 ±0.64 | 5.10± 1.32 | 0.000 |

| 18:1 t (Oleic acid) | 4.54± 0.86 | 5.90 ±1.10 | <0.0001 |

| 18:1 n-9 (Oleic acid) | 39.24± 4.84 | 35.10 ±4.16 | 0.311 |

| 18:1n-11 (Oleic acid) | 2.44± 0.66 | 1.60±0.48 | 0.000 |

| 18:2 t (Linoleic acid) | 2.12 ±0.47 | 2.96± 0.52 | 0.330 |

| 18:2 n-6 (Linoleic acid) | 12.71 ±3.02 | 10.54± 1.91 | 0.630 |

| 18:3 n-9 (Linolenic acid) | 0.64± 0.16 | 0.50± 0.12 | 0.840 |

| CLA (Conjugated Linoleic acid) | 1.08± 0.24 | 0.69± 0.14 | 0.019 |

| 20:4 n-6 (Arachidonic acid) | 0.56± 0.13 | 0.25± 0.07 | 0.025 |

| 20:5 n-3 (Eicosapentaenoic acid) | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.15± 0.05 | 0.101 |

| 22:6 n-3 (docosahexaenoic acid) | 0.18± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.277 |

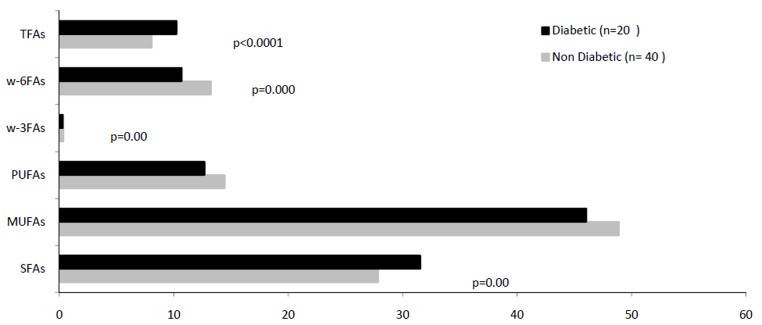

A 100% increase in the amount of FFA 18:0 (p=0.000) and 35% decrease in the level of 18:1n-11(p=0.000) were observed in the diabetic patients’ subcutaneous adipose tissue. Also, the content of arachidonic acid (20:4n-6) (p=0.025) and its precursor linoleic acid (18:2n-6) (p=0.040) in subcutaneous adipose tissue showed a considerable reduction in the diabetic patients (Fig. 1). In addition to the level of 18:0, a significant rise was also observed in the content of 16:1n-7(p=0.033) and conjugated linolenic acids (CLAs) (p=0.019) in this tissue in diabetic patients (Fig. 1).

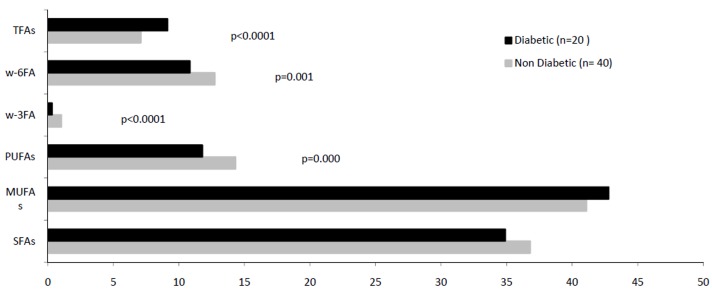

Fig. 1 .

Comparison of fatty acids' profiles of epicardial adipose tissue in the patients with/ without diabetes, candidate for coronary artery bypass graft (TFAs: trans fatty acids, w-6FAs: w-6fatty acids, w-3FAs: w-3fatty acids, PUFAs: polyunsaturated fatty acids, MUFAS: monounsaturated fatty acids, SFAs: saturated fatty acids).

The main saturated fatty acid (SFA) 16:0 showed a substantial (p=0.02) reduction in the diabetic patients’ epicardial adipose tissue. In this tissue, the increase of FFA 18:0 (p=0.003) and CLA (p=0.033) and the decrease of FFA 18:1n-11(p=0.000) were significant (Fig. 2). In contrast to subcutaneous adipose tissue, the contents of arachidonic acid and its precursor linoleic acid in the epicardial adipose tissue were not affected by diabetes, but the epicardial level of FFA w3 (20:5n-3) (p=0.015) and 22:6n-3 (p=0.000) showed 50% reduction in this patients (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 .

Comparison of fatty acids' profiles of subcutaneous adipose tissue in the patients with/ without diabetes, candidate for coronary artery bypass graft (TFAs: trans fatty acids, w-6FAs: w-6fatty acids, w-3FAs: w-3fatty acids, PUFAs: polyunsaturated fatty acids, MUFAS: monounsaturated fatty acids, SFAs: saturated fatty acids).

Discussion

In this study, the profile of FFAs in subcutaneous and epicardial adipose tissues was evaluated in diabetic and non-diabetic patients candidate for CABG. Two groups were similar in terms of age, weight, BMI, the ratio of M/F, and smoking. In spite of receiving hypoglycemic medication, blood sugar as well as HbA1c were high in the diabetic patients and significantly different from the control group.21 This shows that blood sugar in the diabetic patients was not well controlled.Serum level of triglyceride was also high in the diabetic patients, which indicates long-term high glucose levels in these patients. A considerable increase in unsaturated fatty acids 12:0 and16:0 and a significant decrease in unsaturated fatty acid 20:4n-6 levels were observed in the FFA fraction of serums obtained from diabetic patients with severe vascular involvement, candidate for CABG. To our best knowledge, this is the first report on the contents of FFAs in the serum of patients with type II diabetes of mellitus. Since the serum FFAs come from adipose tissue mobilization rather than diet,22 it can be considered as a pattern of fatty acids’ contents in the total body fat tissue.

Palmitic acid is a major saturated FFA in serum. It has been reported that this FFA prevents the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle and formation of atherosclerotic plaques.23 The rise of palmitic acid concentration in the serum of obese patients with metabolic syndrome has been reported.24 The reduction of serum level of arachidonic acid in diabetic patients confirms the role of this FFA in the secretion of insulin from pancreatic β cells.25 It is not clear whether the increase of 16:0 and decrease of 20:4n-6 in the serum of diabetic patients is associated with cardiovascular complications. The increase of 16:0 and 18:0 in the serum and decrease of 18:1n-9 in the serum phospholipid fraction of diabetic patients has previously been reported.26 Also, among PUFAs, a large decline of 18:2n-6, 20:3n-6 and 18:3n-3 concentration in the serum of diabetic patients has been observed.26 The present study indicates a significant elevation of saturated FFAs and decline of MUFAs, 18:2n-6 and 18:3n-9 concentrations in the serum of diabetic patients. A positive and independent relation between 16:0 and 18:0 serum phospholipid fractions with incidence of diabetes has been reported.27 The differences in the remaining FFAs profile in the serum phospholipid fraction between the diabetic and non-diabetic patients undergoing CABG observed in the present study could be due to the differences in the patients’ diet. The relation between the profile of plasma phospholipid FFAs and patients’ diet has previously been reported.28

In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, a strong relationship has been reported between concentration of SFAs and PUFAs in serum phospholipid fraction and dietary style.29 The plasma MUFAs are mainly endogenous and are not affected by diet. Therefore, the reduction of MUFAs in the diabetic patients could be due to the disease.

We have previously demonstrated that in non-diabetic patients undergoing CABG the content of SFAs in epicardial adipose tissue is more than that in subcutaneous adipose tissue. According to that study, the pattern of relation between the fatty acids in epicardial adipose tissue and serum cardiovascular risk factors is different from that in the subcutaneous adipose tissues.11 In another study, we also reported that in high cholesterol fed rabbits, the change of epicardial FFAs’ (FFAs) profile was high and its compositions were different from subcutaneous adipose tissue’s.12

Access to epicardial adipose tissue is limited and there are very few reports on the changes of FFAs’ composition in this tissue. To our knowledge, this study is the first report on the epicardial FFAs’ changes in diabetic patients candidate for CABG. Changes in tissue fatty acids’ composition are largely due to changes in the metabolic activity such as amount of uptake, mobilization and endogenous synthesis that occurs in diabetes.30

Our results indicate a significant reduction in palmitic acid (16:0) level in the epicardial adipose tissue of the diabetic patients. On contrary, there was a significant increase in FFA18:0 level in both the epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissues of patients. The findings show that palmitic acid prevents atherosclerosis through inhibiting proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells,23 while stearic acid (18:0) is not very active biologically.31

The metabolic rate in epicardial adipose tissue and its metabolic exchange with the vessel wall is much more than other adipose tissues.32 The finding of our study highlights the influence of diabetes on epicardial atherosclerotic changes and is in line with the previous studies. In the present study, a significant reduction of 18:1n-11 level in both epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissues was observed in the diabetic patients, but the change in the subcutaneous adipose tissue is overwhelming. It has been shown that oleic acid, unlike palmitic acid, stimulates the incidence and progression of atheroma via stimulation of vascular smooth muscle cells’ proliferation.33 A considerable reduction in the contents of fatty acids w3 (20:5n-3 and 22:6n-3) and their precursor, 18:2n-6, in epicardial adipose tissue which was observed in the present study, is in parallel with the results of Garaulet et al. study.34 These authors showed a significant decrease of DHA in visceral tissue of morbidly obese patients. The present study also revealed a significant reduction of subcutaneous adipose tissue level of arachidonic acid (20:4n-6) in the diabetic patients. Arachidonic acid has an anti-diabetic role in stimulating insulin secretion from β cells.35 The fatty acid reduction in the vessel wall of diabetic patients has also been reported.36 CLA and trans fatty acids’ changes in the epicardial adipose tissue in the diabetic patients are more than that in the subcutaneous adipose tissue. However, a significant increase of these fatty acids is seen in both tissues in diabetic patients. The relationship between the level of trans fatty acid and food intake has not been reported so far. Therefore, the change in the profile of fatty acids in the tissues is a pattern of metabolic changes caused by diabetes. It has been shown that atherosclerosis can be remarkably affected by trans fatty acids.37

The results of this study were limited to patients candidate for CABG with more than 75% vascular involvement and, therefore, not comprehensive. Although both groups were matched in terms of anthropometric specifications and lipid profile (except triglyceride), the type of nutrition and disease control can affect the results. However, in order to maximally match the studied groups, individuals with hypercholesterolemia and hypertension were excluded from this study.

Conclusion

The effect of diabetes on the fatty acids’ profile of epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissues is not equal. The significant decrease of 16:0 and w3 fatty acids and increase of trans and conjugated fatty acids in epicardial adipose tissue in the diabetic patients may worsen the formation of atheroma in the related arteries.

Ethical issues

The proposal was approved by Regional Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Competing interests

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Robicsek F, Thubrikar MJ. The freedom from atherosclerosis of intramyocardial coronary arteries: reduction of mural stress-a key factor. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg . 1994;8:228–35. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaowalite N, Lopez–Jimenez F. Epicardial adipose tissue: Friendly companion or hazardous neihbour for adjacent coronary arteries? Eur Heart J 2008;29:695-7. Friendly companion or hazardous neihbour for adjacent coronary arteries? Eur Heart J . 2008;29: Friendly companion or hazardous neihbour for adjacent coronary arteries? Eur Heart J 2008;29. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renò F, Sabbatini M, Bosetti M, Laroche G, Mantovani D, Cannas M. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy application to vascular biology: comparative analysis of human internal mammary artery and saphenous vein wall. Cells Tissues Organs . 2003;175:186–91. doi: 10.1159/000074940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami G, Ghanbarian E, Masoumi M, Rahimi Z, Rezwan Madani F. Comparison of fatty acid profiles of aorta and internal mammary arteries in patients with coronary artery disease. Clin Chim Acta . 2006;370:143–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajar GR, Haeften TW, Visseren FLJ. Adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity, diabetes, and vascular diseases. Eur Heart J . 2008;29:2959–71. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsari C, Dumesic DA, Patterson BW, Votruba SB, Jensen MD. Plasma free fatty acid storage in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue in postabsorptive women. Diabetes . 2008;57:1186–94. doi: 10.2337/db07-0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannukainen JC, Kalliokoski KK, Borra RJ, Viljanen AP, Janatuinen T, Kujala UM. et al. Higher Free Fatty Acid Uptake in Visceral Than in Abdominal Subcutaneous Fat Tissue in Men. Obesity . 2010;18:261–5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MD. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ: implications of its distribution on free fatty acid metabolism. Eur Heart J Suppl . 2006;8:B13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Momesso DP, Bussade I, Epifanio MA, Schettino CD, Russo LA, Kupfer R. Increased epicardial adipose tissue in type 1 diabetes is associated with central obesity and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract . 2011;91:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K, Anzai T, Jinzaki M, Yamada M, Jo Y, Maekawa Y. et al. Increased epicardial fat volume quantified by 64-multidetector computed tomography is associated with coronary atherosclerosis and totally occlusive lesions. Circ J . 2009;73:1927–33. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezeshkian M, Noori M, Najjarpour-Jabbari H, Abolfathi A, Darabi M, Darabi M. et al. Fatty acid composition of epicardial and subcutaneous human adipose tissue. Metab Syndr Relat Disord . 2009;7:125–31. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezeshkian M, Rashidi MR, Varmazyar M, Hanaee J, Darbin A, Nouri M. Influence of a high cholesterol regime on epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue Fatty acids profile in rabbits. Metab syndrome relat disord . 2011;9:403–9. doi: 10.1089/met.2011.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novgorodtseva TP, Karaman YK, Zhukova NV, Lobanova EG, Antonyuk MV, Kantur TA. Composition of fatty acids in plasma and erythrocytes and eicosanoids level in patients with metabolic syndrome. Lipids Health Dis . 2011;10:82–8. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aas V, Hessvik NP, Wettergreen M, Hvammen AW, Hallén S, Thoresen GH, Rustan AC. Chronic hyperglycemia reduces substrate oxidation and impairs metabolic switching of human myotubes. Biochim Biophys Acta . 2011;1812:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CP, Hsu HL, Hung WC, Yu TH, Chen YH, Chiu CA. et al. Increased epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) volume in type 2 diabetes mellitus and association with metabolic syndrome and severity of coronary atherosclerosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) . 2009;70:876–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgun H, Canpolat U, Hazırolan T, Ateş AH, Sunman H, Dural M, et al. Increased epicardial fat tissue is a marker of metabolic syndrome in adult patients. Int J Cardiol 2011;16. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerramasu A, Dey D, Venuraju S, Anand DV, Atwal S, Corder R, et al. Increased volume of epicardial fat is an independent risk factor for accelerated progression of sub-clinical coronary atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2011;2. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib OMN. Guidelines for the prevention, management and care of diabetes mellitus. Cairo: WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. Extraction of Lipids in Solution by the Method of Bligh & Dyer. Can J Biochem Physiol . 1959;37:911–7. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage G, Roy CC. Direct transesterification of all classes of lipids in a one-step reaction. J Lipid Res . 1986;27:114–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg IJ. Diabetic Dyslipidemia: Causes and Consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 2001;86:965–71. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali AH, Koutsari C, Mundi M, Stegall MD, Heimbach JK, Taler SJ. et al. Free fatty acid storage in human visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue: role of adipocyte proteins. Diabetes . 2011;60:2300–7. doi: 10.2337/db11-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu C, Zhu L, Jiang X, Chen X, Qi X. et al. PGC-1alpha inhibits oleic acid induced proliferation and migration of rat vascular smooth muscle cells. PLoS One . 2007;2:e1137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kien CL, Bunn JY, Ugrasbul F. Increasing dietary palmitic acid decreases fat oxidation and daily energy expenditure. Am J Clin Nutr . 2005;82:320–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persaud SJ, Muller D, Belin VD, Kitsou-Mylona I, Asare-Anane H, Papadimitriou A. et al. The role of arachidonic acid and its metabolites in insulin secretion from human islets of langerhans. Diabetes . 2007;56:197–203. doi: 10.2337/db06-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Platat C, Drai J, Oujaa M, Schlienger JL, Simon C. Plasma fatty acid composition is associated with the metabolic syndrome and low-grade inflammation in overweight adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr . 2005;82:1178–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Folsom AR, Zheng ZJ, Pankow JS, Eckfeldt JH. Plasma fatty acid composition and incidence of diabetes in middle-aged adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Clin Nutr . 2003;78:91–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodson L, Skeaff CM, Fielding BA. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and blood in humans and its use as a biomarker of dietary intake. Prog Lipid Res . 2008;47:348–80. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Folsom AR, Shahar E, Eckfeldt JH. Plasma fatty acid composition as an indicator of habitual dietary fat intake in middle-aged adultsThe Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study Investigators. Am J Clin Nutr . 1995;62:564–71. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajer GR, van Haeften TW, Visseren FL. Adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity, diabetes, and vascular diseases. Eur Heart J . 2008;29:2959–71. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubresse JC. Atherosclerosis and nutrition. Rev Med Brux . 2000;21:A359–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobellis G, Bianco AC. Epicardial adipose tissue: emerging physiological, pathophysiological and clinical features. Trends Endocrinol Metab . 2011;22:450–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun LB, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Zhang H, Xu W, Zhang J. et al. Serum palmitic acid-oleic acid ratio and the risk of coronary artery disease: a case-control study. J Nutr Biochem . 2011;22:311–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaulet M, Hernandez-Morante JJ, Tebar FJ, Zamora S. Relation between degree of obesity and site-specific adipose tissue fatty acid composition in a Mediterranean population. Nutrition . 2011;27:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persaud SJ, Muller D, Belin VD, Kitsou-Mylona I, Asare-Anane H, Papadimitriou A. et al. The role of arachidonic acid and its metabolites in insulin secretion from human islets of langerhans. Diabetes . 2007;56:197–203. doi: 10.2337/db06-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte M, Claire M, Deneuville M, Wiernsperger N. Fatty acid composition of phospholipids and neutral lipids from human diabetic small arteries and veins by a new TLC method. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids . 1998;59:363–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(98)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benatar JR, Gladding P, White HD, Zeng I, Stewart RA. Trans-fatty acids in New Zealand patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil . 2011;18:615–20. doi: 10.1177/1741826710389415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]