Abstract

The Timeline Followback (TLFB) interview has been used extensively in the assessment of alcohol and other substance use. While this methodology has been validated in multiple formats for multiple behaviors, to date no systematic comparisons have been conducted between the traditional interview format and online versions. The present research employed a randomized within-subjects design to compare interview versus online-based TLFB assessments of alcohol and marijuana use among 102 college students. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either the online version first or the in-person interview format first. Participants subsequently completed the second format within 3 days. While we expected few overall differences between formats, we hypothesized that differences might emerge to the extent that participants are more comfortable and willing to answer honestly in an online format, which provides a degree of anonymity. Results were consistent with expectations in suggesting relatively few differences between the online version and the in-person version. Participants did report feeling more comfortable in completing the online version. Moreover, greater discomfort during the in-person assessment was associated with reporting more past-month marijuana use on the online assessment, but reported discomfort did not moderate differences between formats in reported alcohol consumption.

Keywords: alcohol, marijuana, validity, Timeline Followback, online

The Timeline Followback (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) is a measure used to collect detailed alcohol and other drug use information from research participants and clinical populations in community, academic, and medical settings. The traditional TLFB involves a structured interview with the use of a calendar to allow participants to indicate the occasions when they used alcohol and/or other drugs over a particular time period (e.g., 30 days). Since the TLFB is more detailed than standard quantity-frequency measures, it can yield extensive information about patterns, frequencies, and quantities of behavior. This tool can be very useful in helping individuals examine their patterns of substance use, while also helping clinicians and researchers better understand behaviors of individuals struggling with substance abuse problems.

Since its development, the TLFB has been adapted to capture important substance use behavior in diverse formats. In addition to in-person interviews (Sobell, Sobell, Leo, & Cancilla, 1988), the TLFB has demonstrated reliability and validity when facilitated by an interviewer in group settings (LaBrie, Pedersen, & Earleywine, 2005; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2006) and over the phone (Breslin, Sobell, Sobell, Buchan, & Kwan, 1996; Sobell, Brown, Leo, & Sobell, 1996). It has also demonstrated utility when self-administered in written forms (Collins, Kashdan, Koutsky, Morsheimer, & Vetter, 2008), by automated telephone prompts (Maisto, Conigliaro, Gordon, McGinnis, & Justice, 2008; Searles, Helzer, Rose, & Badger, 2002), and by computer-based formats in laboratory settings (Sobell, Brown et al., 1996). The TLFB has been used with a variety of populations including adolescents (e.g., Levy et al., 2004), college students (e.g., Fishburne & Brown, 2006; Sobell, Sobell, Klajner, Pavan, & Basian, 1986), homeless adults (e.g., Sacks, Drake, Williams, Banks, & Herrell, 2003) and psychiatric outpatients (e.g., Carey, 1997; Roy et al., 2008). In addition to alcohol use, the TLFB has been used to collect individual data on marijuana use (e.g., Donohue et al., 2004; Sobell, Sobell et al., 1996), cigarette smoking (e.g., Brown, Burgess, Sales, Evans, & Miller, 1998; Gariti, Alterman, Ehrman, & Pettinati, 1998), risky sexual behavior (e.g., Carey, Carey, Maisto, Gordon, & Weinhardt, 2001; Copersino, Meade, Bigelow, & Brooner, 2010), and use of illicit drugs such as cocaine and heroin (e.g., Ehrman & Robbins, 1994; Hersh, Mulgrew, VanKirk, & Kranzler, 1999).

Online Methods of Data Collection

As technology advances and interactive Internet-based assessments become more practical and common, it is important to validate this widespread measure for use in these domains. The benefits of collecting data using the Internet include ease and expanded time of survey access and recruitment, standardization of questions, reduced cost and time, and fewer data entry errors (Moore, Soderquist, & Werch, 2005; Riva, Terruzi, & Anolli, 2003; Strecher, 2007). Electronic methods may further provide a greater sense of anonymity, thereby reducing underreporting of undesirable or stigmatizing behaviors such as underage and illicit substance use (Farvolden, Cunningham, & Selby, 2009; Turner et al., 1998).

Existing studies have found relatively minor or no differences between data collected electronically versus more traditional paper-and-pencil and interview methods (Khadjesari et al., 2009; Kypri, Gallagher, & Cashell-Smith, 2004; Miller et al., 2002). In general, alcohol use measures such as the Alcohol Use Identification Test (Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993) and the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (White & Labouvie, 1989) appear to collect comparable data in both online and paper-and-pencil formats. To date, little research has evaluated standard TLFB interviews with self-administered Internet-based TLFB assessments. Hoeppner, Stout, Jackson, and Barnett (2010) compared an online 7-day TLFB assessment to standard 30-day in-person TLFB interviews and found more proximal reports of behavior within the 7-day TLFB may have been more accurate than retrospectively reported behavior collected during the in-person interview. However, it is unclear if standard TLFB formats (e.g., retrospective reports of past 90 days) compare to traditional and online formats. Concerns exist when online translations of traditional paper-and-pencil or interview assessments are utilized in research without empirically testing the validity of the measure in the new format (Buchanan et al., 2005; Del Boca & Darkes, 2003; Gosling, Vazire, Srivastava, & John, 2004). Thus, the current study employed a randomized within-subjects design to evaluate utility of an online TLFB assessment. We compared participants’ reported past 90-day drinking and marijuana use on a standard in-person TLFB interview to a similar online-delivered version. It was hypothesized that participants would report similar amounts of drinking and marijuana use during both administrations of the TLFB. However, as a greater degree of anonymity from online questionnaires may help assist in greater reports of illegal and stigmatized behaviors (Turner et al., 1998), we hypothesized that those participants who reported less comfort during the in-person TLFB would report higher levels of alcohol and marijuana use on the online TLFB.

Method

Participants

Participants were 130 college students from a northwestern university who were enrolled in Psychology 101 courses during the 2010–2011 academic year. Students had the option to sign up for this study or approximately 20 other studies to receive extra credit for the course. Students who chose to participate in this study were asked to complete in-person and online forms of the TLFB assessment for both alcohol and marijuana use. These drugs were chosen due to their prevalence in college student populations (approximately 80% drink; one third use marijuana [Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2010]). Of 130 participants, 102 (79%) completed both the in-person TLFB interview and the online TLFB. Only participants who completed both assessments were included in analyses. These participants had a mean age of 19.34 (SD = 1.44) and 52% were women. Forty-eight percent identified as White/Caucasian, 32% as Asian/Asian American, 4% as Hispanic/Latino(a), 2% as Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 7% identified as “mixed ethnicities,” and 7% identified as “other ethnicities.” Most (78%) participants were first- or second-year students. There were no differences in demographic variables or substance use between completers and noncompleters.

Procedures

Participants were randomized to receive the in-person or online assessment first. Participants who received the in-person assessment first (n = 55) read and signed a Human Subjects approved consent form during this first meeting, while participants in the online first condition (n = 47) read and electronically signed the consent form online. Participants were given a final survey after completing their second TLFB format. Confidential PIN codes were used in data collection. To capture 90 days of behavior for analyses, participants completed both TLFB assessments for the past 100 days, in order to match days between the two assessments for analyses. Online-first participants received a link to the online TLFB via email and were asked to fill it out within 3 days. Participants attended the in-person interview between 1 and 3 days after they filled out the online TLFB; likewise, in-person first participants attended a scheduled in-person interview and were emailed a link to the online TLFB 1 to 3 days after the interview. All participants completed the second assessment between 1 and 3 days after filling out their first assigned TLFB assessment.

During both assessments, participants indicated number of standard drinks they had each day (e.g., 12-oz. beer, 4-oz. wine, 1.25-oz. shot of distilled spirits), number of hours spent drinking that day, and number of times they used marijuana on each day. As per Sobell and Sobell (2000), participants indicated “marker days” on both versions to help assist their recall of behavior. The online version of the TLFB imitated the in-person calendar with one month per screen and input text boxes in each day for the participant to enter their data. The participant could browse forward or backward to different months using on-screen buttons, then clicked a “submit” button to finalize their answers. For the in-person TLFB interview, participants were randomly assigned to either a male or female (one of each) undergraduate research assistant who helped them complete the in-person TLFB assessment. To standardize procedures, during the in-person interview the research assistant read the same instructions that were provided on the online version (modified from Sobell & Sobell, 2000). Standard drink information and suggestions for memory recall were provided similarly in both formats.

Characteristics of Assessments

After completing their second version of the TLFB, participants completed five 5-point Likert-type scales regarding the degree of comfort felt during the in-person interview and on the online assessment (0 = very uncomfortable to 4 = very comfortable; 2 = neutral), difficulty recalling behavior over the past 90 days during the in-person interview and on the online assessment (0 = not at all difficult to 4 = extremely difficult), and the degree to which they remembered their responses from the first version of the assessment when filling out the second version (0 = not at all to 4 = to a large extent). Participants who received the online TLFB second received this questionnaire in an online format while those who received the in-person TLFB second received this questionnaire as a paper-and-pencil survey.

Analytic Plan

While the TLFB assessment can yield multiple pieces of important substance use information, we chose to examine 10 outcome variables that would provide a range of behaviors typically assessed with the TLFB. Specifically, we examined total drinks consumed in the past month (30 days) and over the entire 90-day period; drinking days in the past 30 days and over the 90-day period; two calculated variables of average drinks per occasion in the past 30 days and past 90 days (total drinks divided by drinking days); peak drinks consumed in the past 30 and 90 days; and days used marijuana in the past 30 and 90 days. We first conducted a series of paired samples t tests to determine if there were within-subjects mean differences between in-person and online TLFB versions. We also examined correlations between comparable variables in each version. We next conducted a series of repeated measures ANOVAs with degree to which participants remembered their answers between the first and second assessment as a covariate. These analyses were conducted to determine how remembering of responses influenced reports between TLFB versions. Finally, to examine the hypothesis that participants may report more illegal behavior on the online assessment if they experienced some discomfort completing the assessment in-person, we examined the differences in past 30-day and 90-day marijuana use between the in-person and online versions of the TLFB by the level of comfort reported during the in-person interview and the online assessment. Significant interactions were graphed according to Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken (2003) with high and low values of the covariate specified as one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively.

Results

Differences Between TLFB Versions

Table 1 contains the means and standard deviations for reported behavior on the in-person and online TLFBs in the past 90 days and the past 30 days. Overall, participants’ drinking behavior was not reported as statistically different between versions of the TLFB. Correlations between the drinking variables ranged from r = .87 to r = .95. The exception was average drinks per occasion, which was significantly higher on the online version for the past 90 days, t(99) = 2.67, p < .001, d = .28, and the past 30 days, t(92) = 2.76, p < .01, d = .30. “Days used marijuana” was also significantly different across the two versions of the TLFB, with higher reported frequencies on the online version for both the past 90 days, t(101) = 2.81, p < .01, d = .31, and past 30 days, t(101) = 2.75, p < .01, d = .30. There were no assessment condition × remembering of responses interactions for any of the 10 outcomes examined.

Table 1.

Within Subject Means and Correlations Comparing Individual TLFB to Online TLFB

| In-person administration |

Online administration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | Pearson’s correlation coefficient | |

| Past month | |||||

| Total drinks | 23.26 | (28.34) | 24.76 | (33.34) | 0.94 |

| Drinking days | 4.94 | (4.55) | 4.88 | (4.78) | 0.91 |

| Average drinks | 4.43 | (2.14) | 4.78 | (2.41)* | 0.87 |

| Peak drinks | 6.81 | (4.19) | 6.92 | (4.40) | 0.88 |

| Days used marijuana | 3.24 | (7.00) | 3.79 | (7.68)* | 0.97 |

| Past 3 months | |||||

| Total drinks | 67.16 | (81.89) | 66.59 | (81.85) | 0.95 |

| Drinking days | 13.97 | (13.65) | 13.47 | (13.61) | 0.93 |

| Average drinks | 4.27 | (2.01) | 4.50 | (2.14)* | 0.92 |

| Peak drinks | 8.00 | (4.51) | 8.09 | (4.59) | 0.90 |

| Days used marijuana | 8.34 | (17.63) | 10.01 | (20.74)* | 0.96 |

| Assessment characteristics | |||||

| Comfort level | 3.02 | (1.16) | 3.45 | (0.98)* | 0.53 |

| Difficulty remembering | 2.08 | (1.07) | 2.04 | (1.20) | 0.53 |

Note. All correlations significant at p < .001.

Significant difference between in-person and online administration (see text).

Characteristics of the Assessments

There were no observable effects on order of administration with the exception of drinking days per month reported on the online TLFB. Those who received the online TLFB first reported about two more drinking days in the past 30 days than those who received the in-person assessment first, t(100) = 2.05, p < .05, partial η2 = .02. Participants reported comparable means for difficulty remembering behavior on both versions of the TLFB (see Table 1). However, participants reported a greater comfort level when filling out the online TLFB compared to the in-person TLFB, t(98) = 4.11, p < .001, d = .41. Participants reported a mean of 1.98 (SD = 1.00) for the item assessing the degree they remembered their responses from the first version when filling out the second version. This corresponded to a response option of “to a fair extent.”

Comfort level on the assessments

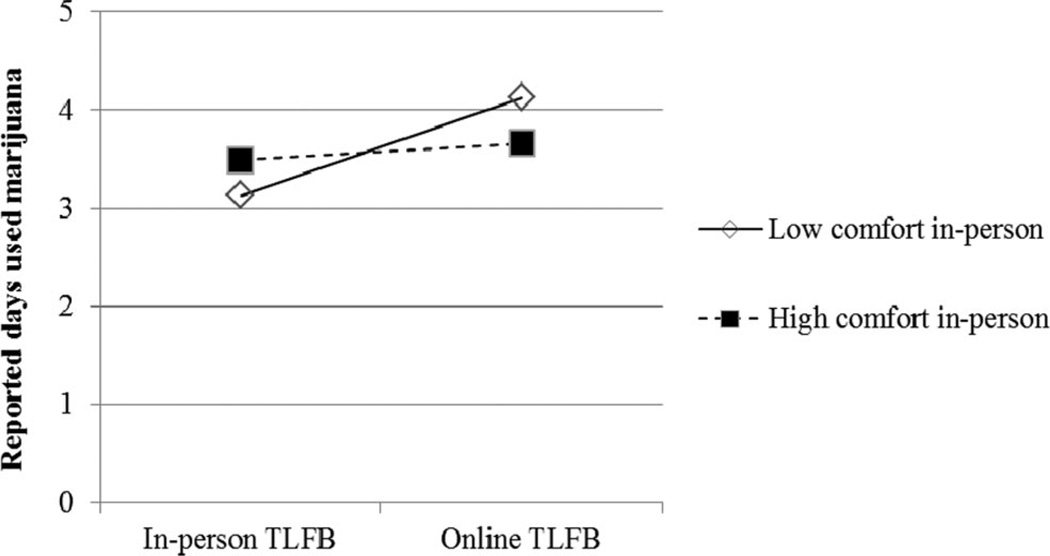

While there was no significant effect for 90-day marijuana use, there was an assessment condition × in-person comfort level interaction for 30-day reported marijuana use, such that those participants who reported lower levels of comfort during the in-person TLFB experienced greater differences in their responses between assessments, F(1, 97) = 4.04, p < .001, partial η2 = .04. Participants with lower levels of comfort during the in-person TLFB reported approximately one more day of marijuana use in the past month online, while those with higher levels of comfort reported similar marijuana using days on both assessments (see Figure 1). There were no significant condition × online version comfort level interactions for 30- or 90-day reported marijuana use.

Figure 1.

In-person comfort level predicting reported marijuana using days in the past month.

Discussion

The TLFB has been extensively evaluated in varying formats for a number of substances and behaviors, yet little research has systematically compared the in-person interview format with an online version. This is important because advantages of online assessment (e.g., accessibility, standardization, low cost) would be of little value without confidence in the reliability and validity of data provided. Overall results supported previous research suggesting few differences between online formats and traditional assessments (Khadjesari et al., 2009; Kypri et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2002). This research expands on the work of Hoeppner and colleagues (2010) and offers a different comparison in suggesting, at least in this study, that retrospectively collected online TLFB data was comparable to in-person retrospectively collected TLFB data. Observed differences were small but consistently in the expected direction of more reported behavior on the online version.

We did find some support for the notion that individuals may feel more at ease in completing online assessments and that less comfort in the in-person interview was associated with reporting more marijuana use in the past month on the online TLFB. However, it is also possible that differences observed may have resulted from interviewer prompts helping participants better recall the days they may not have used substances. Furthermore, participants may have overestimated their marijuana use during the online assessment. While TLFB assessments may be superior to single-item measures (e.g., “how many days did you drink alcohol in the past month?”) in terms of the richness of data collected (Carney, Tennen, Affleck, Del Boca, & Kranzler, 1998; Del Boca & Darkes, 2003; Sobell & Sobell, 1995), it is unclear which format yielded more accurate data. Future work can compare data from the online-based TLFB with daily reports of behavior or collateral reports. There is substantial value in online-based methods if the provision of greater comfort allows individuals to report more accurate behavior compared to in-person and paper-and-pencil formats.

The present research supports flexibility in the development of intervention and treatment protocols utilizing online or in-person assessments. Many brief in-person interventions with college students (e.g., BASICS; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999) require assessment of drinking and drug use that is used in feedback during the intervention. Collecting these data ahead of time via online surveys can reduce the burden on campus resources by using in-person time for actual intervention content rather than data gathering. Additionally, successful screening and interventions for alcohol and drug problems have been implemented entirely using web-based methods (e.g., Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Walter, 2009; Sinadinovic, Berman, Hasson, & Wennberg, 2010), and individuals may actually prefer these assessment and intervention methods to face-to-face ones (Kypri, Saunders, & Gallagher, 2003).

There are pros and cons of online versus in-person assessments that are likely to vary considerably based on available resources and program goals. Online assessment may not be feasible for all programs or populations targeted. College students may have a higher comfort level with online assessments relative to older adults or other populations. In-person assessments offer the opportunity to build rapport, correct inconsistencies, and observe and respond to nonverbal behaviors, defensiveness, and/or distractions. The present findings suggest these factors can be considered without having to also be as concerned about whether online assessment will provide comparable responses regarding alcohol or drug use. For the most part, they do appear to provide comparable responses and related difficulties in behavior recall, though consideration of the comfort level of respondents is important.

Several limitations are worth mentioning in considering the present research. First, the reported correlations between substance use items on the two versions do not necessarily suggest equivalent mean scores between assessments. Additionally, the sample size was small and findings may not generalize to other populations. College students differ in important ways from the population at large and from populations who may seek treatment for alcohol or other substances. Findings related to drinking days in the past month are qualified by the order effects observed related to this variable. The marijuana assessment was limited to days used and did not include a measure of quantity, and it is unclear whether differences in marijuana use between formats would be similar with more precise assessments. The TLFB interviewers in this study were undergraduate research assistants without extensive training in clinical assessment. While interviewers attended supervision and discussed their interviews with supervisors, sessions were not recorded and fidelity to protocol could not be objectively verified. Finally, although we asked participants the degree to which they recalled their answers between assessments, memory effects were likely present when recalling behaviors during the second assessment. Studies with longer periods between assessments are necessary.

In sum, the present research provides a unique contribution to further establishing utility of the TLFB administered in an online format. Overall, differences between online and in-person formats were relatively small. Some support was found for a higher level of comfort in completing the online version, and a lower level of comfort during the in-person interview was associated with reporting more past month marijuana use during the online version of the assessment.

Acknowledgments

Manuscript preparation was supported by a National Research Service Award (1F31AA018591) to Eric R. Pedersen from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

Contributor Information

Eric R. Pedersen, Department of Psychology, University of Washington

Joel Grow, Department of Psychology, University of Washington.

Sean Duncan, Department of Psychology, University of Washington.

Clayton Neighbors, Department of Psychology, University of Houston.

Mary E. Larimer, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington

References

- Breslin C, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Buchan G, Kwan E. Aftercare telephone contacts with problem drinkers can serve a clinical and research function. Addiction. 1996;91:1359–1364. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.919135910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan T, Ali T, Heffernan TM, Ling J, Parrott AC, Rodgers J, Scholey AB. Nonequivalence of on-line and paper-and-pencil psychological tests: The case of the prospective memory questionnaire. Behavior Research Methods. 2005;37:148–154. doi: 10.3758/bf03206409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB. Reliability and validity of the timeline follow-back interview among psychiatric outpatients: A preliminary report. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, Weinhardt LS. Assessing sexual risk behavior with the timeline follow-back (TLFB) approach: Continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. International Journal of STDs & AIDS. 2001;12:365–375. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney MA, Tennen H, Affleck G, Del Boca FK, Kranzler HR. Levels and patterns of alcohol consumption using timeline follow-back, daily diaries and real-time “electronic interviews”. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:447–454. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Kashdan TB, Koutsky JR, Morsheimer ET, Vetter CJ. A self-administered timeline followback to measure variations in underage drinkers’ alcohol intake and binge drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copersino ML, Meade C, Bigelow G, Brooner R. Measurement of self-reported HIV risk behaviors in injection drug users: Comparison of standard versus timeline follow-back administration procedures. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: State of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 2003;98(suppl 2):1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue B, Azrin NH, Strada MJ, Silver NC, Teichner G, Murphy H. Psychometric evaluation of self- and collateral timeline follow-back reports of drug and alcohol use in a sample of drug-abusing and conduct-disordered adolescents and their parents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:184–189. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ. Reliability and validity of 6-month timeline reports of cocaine and heroin use in a methadone population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:843–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farvolden P, Cunningham J, Selby P. Using E-health programs to overcome barriers to the effective treatment of mental health and addiction problems. Journal of Technology in Human Services. 2009;27:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fishburne JW, Brown JM. How do college students estimate their drinking? Comparing consumption patterns among quantity-frequency, graduated frequency, and timeline follow-back methods. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2006;50:15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gariti PW, Alterman AI, Ehrman RN, Pettinati HM. Reliability and validity of the aggregate method of determining number of cigarettes smoked per day. The American Journal on Addictions. 1998;7:283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Vazire S, Srivastava S, John OP. Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about Internet questionnaires. American Psychologist. 2004;59:93–104. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh D, Mulgrew CL, Van Kirk J, Kranzler HR. The validity of self-reported cocaine use in two groups of cocaine abusers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:37–42. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeppner BB, Stout RL, Jackson KM, Barnett NP. How good is fine-grained timeline follow-back data? Comparing 30-day TLFB and repeated 7-day TLFB alcohol consumption reports on the person and daily level. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1138–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2009: Volume I, Secondary school students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. (NIH Publication No. 10–7584). [Google Scholar]

- Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Kalaitzaki E, White IR, McCambridge J, Godfrey C, Wallace P. Test–retest reliability of an online measure of past week alcohol consumption (the TOT-AL), and comparison with face-to-face interview. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Gallagher SJ, Cashell-Smith ML. An Internet-based survey method for college student drinking research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Saunders JB, Gallagher SJ. Acceptability of various brief intervention approaches for hazardous drinking among university students. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2003;38:626–628. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie J, Pedersen ER, Earleywine M. A group-administered timeline followback assessment of alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:693–697. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Sherritt L, Harris S, Gates E, Holder D, Kulig JW, Knight JR. Test–retest reliability of adolescents’ self-report of substance use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:1236–1241. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000134216.22162.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Conigliaro JC, Gordon AJ, McGinnis KA, Justice C. An experimental study of the agreement of self-administration and telephone administration of the timeline followback interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:468–471. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ET, Neal DJ, Roberts LJ, Baer JS, Cressler SO, Metrik J. Test-retest reliability of alcohol measures: Is there a difference between internet-based assessment and traditional methods? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ, Soderquist J, Werch C. Feasibility and efficacy of a binge drinking prevention intervention for college students delivered via Internet versus postal mail. Journal of American College Health. 2005;54:38–44. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.1.38-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Walter T. Internet-based personalized feedback to reduce 21st birthday drinking: A randomized controlled trial of an event specific prevention intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:51–63. doi: 10.1037/a0014386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW. A within-subjects validation of a group administered timeline followback for alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:332–335. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva G, Teruzzi T, Anolli L. The use of the Internet in psychological research: Comparison of online and offline questionnaires. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2003;6:73–80. doi: 10.1089/109493103321167983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M, Dum M, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Simco ER, Manor H, Palmerio R. Comparison of the quick drinking screen and the alcohol timeline followback with outpatient alcohol abusers. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43:2116–2123. doi: 10.1080/10826080802347586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JA, Drake RE, Williams VF, Banks S, Herrell JM. Utility of the time-line follow-back to assess substance use among homeless adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:145–153. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000054930.03048.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles JS, Helzer JE, Rose GL, Badger GJ. Concurrent and retrospective reports of alcohol consumption across 30, 90 and 366 days: Interactive voice response compared with the timeline follow back. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:352–362. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinadinovic K, Berman AH, Hasson D, Wennberg P. Internet-based assessment and self-monitoring of problematic alcohol and drug use. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;42:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol consumption measures. In: Allen JP, Columbus M, editors. Assessing alcohol problems: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) In: American Psychiatric Association, editor. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. pp. 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Buchan G, Cleland PA, Fedoroff I, Leo GI. The reliability of the timeline followback method applied to drug, cigarette, and cannabis use. Paper presented at the 30th Annual Meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy; New York, NY. 1996. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: Assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. British Journal of Addiction. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Klajner F, Pavan D, Basian E. The reliability of a timeline method for assessing normal drinker college students’ recent drinking history: Utility for alcohol research. Addictive Behaviors. 1986;11:149–161. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecher V. Internet methods for delivering behavioral and health-related interventions (e-Health) Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:53–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie E. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]