Abstract

Dispositional optimism is believed to be an important psychological resource that buffers families against the deleterious consequences of economic adversity. Using data from a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin families (N = 674), we tested a family stress model specifying that maternal dispositional optimism and economic pressure affect maternal internalizing symptoms, which, in turn, affects parenting behaviors and children’s social adjustment. As predicted, maternal optimism and economic pressure had both independent and interactive effects on maternal internalizing symptoms, and the effects of these variables on changes over time in child social adjustment were mediated by nurturant and involved parenting. The findings replicate and extend previous research on single-parent African American families (Taylor, Larsen-Rife, Conger, Widaman, & Cutrona, 2010), and demonstrate the generalizability of the positive benefits of dispositional optimism in another ethnic group and type of family structure.

Keywords: dispositional optimism, Family Stress Model, Mexican-origin, parenting, internalizing symptoms

The resources individuals have to cope with difficulties in their lives have important consequences for their emotional and physical well-being (Ensel & Lin, 1991). The present study examined a personality characteristic, dispositional optimism, which contributes to successful adaptation in the face of hardships. Specifically, we attempted to replicate and extend a prior study of African American single mothers (Taylor et al., 2010), which found that maternal optimism reduced the impact of economic pressure on internalizing symptoms and promoted effective parenting. This study was particularly important because most studies have examined dispositional optimism in European American individuals (Carver, Scheier & Segerstrom, 2010). The Taylor et al. (2010) investigation demonstrated that the personal trait of optimism has a protective influence for minority mothers as well.

The present study extends this line of research in two important ways. First, we examined the role of dispositional optimism in family stress processes for Mexican-origin mothers. Earlier research shows that coping styles and strategies can differ among ethnic groups (Njoku, Jason, & Torres-Harding, 2005; Novy, Nelson, Hetzel, Squitieri, & Kennington, 1998), and ethnic differences have been found in how families function when facing stressful life events (Behnke et al., 2008). Cultural influences on optimism have also been found (e.g., Chang, 2001). Thus, it cannot be assumed that the Taylor et al. (2010) findings will apply to Mexican-origin mothers. Second, we evaluated whether dispositional optimism functions as a psychological resource not only for single mothers, but also for mothers in two-parent families who are likely to experience lower levels of stress and strain than single-parent mothers.

Theoretical and Empirical Framework

Economic Pressure and Family Functioning

Our hypotheses derive from the Family Stress Model (FSM) (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). The FSM posits that economic pressure leads to parental emotional distress such as internalizing symptoms, which disrupts positive parenting behaviors (Conger et al., 2010). Parents who are distressed by their own problems tend to be less supportive, warm, and involved with their children. In turn, these parenting behaviors increase risk for child adjustment problems. Although the FSM has been tested with a variety of ethnic and racial groups (Conger et al., 2010), these associations remain understudied in Mexican-origin families (for exceptions, see Mistry, Vandewater, Huston, & McLoyd, 2002; Parke et al., 2004) and the precise role of disposition optimism has received little attention. Examining the effects of economic pressure in Mexican-origin families is important as Latinos constitute one of the most impoverished populations in the U.S. with a 2010 median household income of $37,759, compared with $54,620 for non-Hispanic White households (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2010). Earlier research has shown that extremely poor families suffer the most in terms of economic impacts on child development (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997). Thus, research that examines processes that are associated with maintaining positive parenting behaviors that, in turn, are associated with the positive adjustment of children may have important developmental implications for Mexican-origin youth (Cardoso & Thompson, 2010).

Dispositional Optimism: A Psychological Resource

The present study examines whether mothers’ dispositional optimism disrupts or moderates the causal connections proposed by the FSM and, in turn, predicts positive child adjustment in Mexican-origin families. Dispositional optimism is a relatively stable, general tendency of individuals to expect positive events or conditions in life (Carver et al., 2010). Individual differences in optimism represent differing ways in which people respond to and cope with stressful circumstances. Individuals high in optimism have relatively better psychological adjustment in the face of negative events, report less distress across a range of situations, have more positive social networks, and enjoy better physical health (for a review see Carver et al., 2010; Nes & Segerstrom, 2006; Taylor & Stanton, 2007). Optimistic individuals may have better outcomes as they are more likely to persevere in times of crisis, show higher self-efficacy, and use more effective coping strategies (Carver et al., 2010). Optimism has rarely been examined with Mexican-origin individuals. However, González & González (2008) found that optimism was negatively correlated with depression and positively correlated with life satisfaction in a sample of Mexican-origin college students.

Dispositional optimism has also been linked with positive parenting behaviors in at-risk or vulnerable families (e.g., Kochanska, Aksan, Penney, & Boldt, 2007; Taylor et al., 2010). Optimism was positively associated with maternal warmth and negatively related with hostility and neglect (Hjelle, Busch, & Warren, 1996; Jones, Forehand, Brody, & Armistead, 2002; Taylor, 2011). Additionally, longitudinal studies of African American single mothers show that mothers with relatively more optimistic dispositions are more likely to use competence-promoting parenting practices, which predict greater cognitive, social, and psychological adjustment in children (Brody & Flor, 1998; Brody, Murry, Kim, & Brown, 2002; Kim & Brody, 2005; Taylor et al., 2010).

A few studies have found that dispositional optimism moderates the association between economic pressure and family functioning. Kochanska et al. (2007) found that parents with high levels of demographic risks (e.g., low income and education) and relatively low optimism had lower levels of warm parenting. However, risk was not detrimentally associated with warm parenting for parents with higher levels of optimism. Similarly, Taylor et al. (2010) found that maternal optimism moderated the relation between economic pressure and maternal internalizing symptoms, with more optimistic mothers demonstrating greater resilience to the negative effects of economic stress.

In the present investigation, we hypothesized that the economic stress often experienced by Mexican-origin families would predict greater maternal internalizing symptoms that, in turn, would predict lower levels of involved and nurturing parenting. However, we also expected that optimism would offset some of these negative paths by predicting fewer internalizing symptoms and more positive parenting behaviors. Furthermore, we hypothesized that optimism would reduce the magnitude of the relation between economic pressure and internalizing symptoms as was found by Taylor et al. (2010). Finally, to the extent that involved and nurturing parenting was maintained, we predicted improvements over time in children’s social competence. Social competence is a dimension of positive adjustment that involves the ability to navigate social situations successfully, such as getting along with peers and adults and behaving prosocially at school, (Mistry et al., 2002; Scaramella, Conger, Spoth, & Simons, 2002).

Single-Mother Families

Although the FSM is hypothesized to function in a similar manner in single-parent families, the model has largely been tested with two-parent families (for exceptions see Mistry et al., 2002; Taylor et al., 2010). Single mothers may be particularly susceptible to the negative processes posited by the FSM as they experience greater than average levels of economic hardship and related stresses and strains (e.g., Amato & Keith, 1991; Avison, Ali, & Walters, 2007; Brown & Moran, 1997; Cairney, Boyle, Offord, & Racine, 2003). To test this possibility, we evaluated whether family structure (mothers in single- vs. two-parent families) moderated any of the effects. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to test whether single-parent families are more vulnerable to the stress processes proposed by the FSM than two-parent families.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The California Families Project (CFP) is an ongoing longitudinal study of Mexican-origin families in northern California. Participants at Wave 1 (W1) included 674 two-parent (N = 549, 82%) and single-mother (N = 125, 18%) families with a fifth grade child (mean age = 10.8 years, 49.8% male) who were drawn at random from school rosters during 2006 –2008. Eligible families were of Mexican origin as determined by their ancestry and their self-identification as being of Mexican heritage. Interviews were conducted with the focal children, their mothers, and their fathers (if present). Of the two-parent families, 80% (N = 438) of fathers directly participated in the interviews in W1. Wave 2 (W2) interviews were conducted 1 year later, with 84% (N = 568) of families participating. Children were interviewed using a shorter battery of measures from the original W1 assessment. Mothers reported demographic information about the family. Fathers did not participate in W2 interviews. For both waves of interviews, trained bilingual research staff (most of Mexican heritage) interviewed participants in their homes. Interviews were conducted in Spanish or English based on the preference of each participant.

Measures

Household structure

This dichotomous variable measured the household structure of the families at W1 (0 = two-parent families; 1 = single-parent families). A dummy variable for change in marital status at W2 was also created (0 = no change; 1 = change).1

Economic pressure

Economic pressure was reported by mothers at W1, and consisted of three indicators: unmet material needs (UN), can’t make ends meet (CM), and financial cutbacks (FC). UN included six items rated on a scale ranging from 1 = “not at all true” to 4 = “very true” (α = .91). CM included four items asking mothers if they had difficulty paying their bills during the past 12 months and how much money was left at the end of the month; responses ranged from 1 = “no difficulty at all” to 4 = “a great deal of difficulty” and 1 = “more than enough money” to 4 = “not enough to make ends meet” (α = .77). FC included 7 items regarding their adjustments to financial need (1 = yes, 0 = no) during the past 12 months (α = .65). These items were summed to form an index of cutbacks with a mean score of 1.53 (SD = 1.54).

Mother’s dispositional optimism

Dispositional optimism was reported by mothers at W1 using the six-item Life Orientation Test (LOT-R; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). The LOT-R is the most widely used and well-validated measure of optimism in the psychological literature. Responses ranged from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree”. Sample items included “In uncertain times, you usually expect the best” (α = .56). Items were randomly composited into three parcels (O1 – O3), with the restriction that one positively worded and one negatively worded item was in each parcel. Considerable recent research supports parceling of items to develop multiple indicators of latent constructs to avoid contaminating influences of measurement error when estimating relations among latent variables (Coffman & MacCallum, 2005; Kishton & Widaman, 1994; Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002).

Mothers’ internalizing symptoms

Mothers reported their internalizing symptoms at W1 using three scales from the Mini Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (Clark & Watson, 1995). The indicators for this latent construct were general depression, anhedonic depression, and general distress/anxiety. Mothers were asked how often they had experienced symptoms during the past week. Responses for all items ranged from 1 = “not at all” to 4 = “very much”. General depression was measured with a five-item scale asking whether the individual had felt depressed, discouraged, hopeless, like a failure, and worthless (α = .91). Anhedonic depression included eight items such as whether the individual had felt like nothing was very enjoyable (α = .86). General distress/anxiety had three items asking whether the individual had felt tense or high strung, uneasy, and on edge (α = .78).

Involved parenting

Mothers reported on their involved parenting at W1 using three scales: family routine, maternal monitoring, and educational involvement. Family routine is an eight-item measure developed by Rand Conger. Items were scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = “almost never or never”, to 4 = “everyday” (α = .53). Monitoring is a 10-item scale adapted from Stephen A. Small. Responses ranged from 1 = “almost never or never” to 4 = “almost always or always” (α = .78). Educational involvement is a four-item scale developed by Epstein (1986). Responses ranged from 1 = “never” to 4 = “many times” (α = .78). The measures were randomly composited into three parcels (P1 – P3) to create a latent variable that reflected a variety of involved parenting behaviors.

Nurturant parenting

Nurturant parenting was measured using the 22-item Behavioral Affect Rating Scale, which measures warmth and hostility within close relationships (Conger et al., 2010; Conger et al., 2002). Children reported on their mother’s warmth and hostility toward them at W1. Response categories were modified for the CFP from the original 7-point scale to a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = “almost never or never”, to 4 = “almost always or always” (α = .87). The 22 items were randomly composited into three indicators (N1 – N3) to create a latent variable.

Change in child’s social adjustment

This latent variable consisted of three indicators: peer competence, school attachment, and teacher attachment. These scales were reported by the child during W1 and W2 interviews. Our latent outcome variable reflects change in child adjustment, operationalized as W2 social adjustment controlling for W1 social adjustment. Peer competence was measured using nine items from the Coatsworth Competence Scale, with response options ranging from 1 = “not at all true”, to 4 = “very true” (W1 α = .68; W2 α = .62). School attachment is a 12-item scale developed by Rand Conger, with response options ranging from 1 = “not at all true”, to 4 = “very true” (W1 α = .76; W2 α = .77). Teacher-attachment is a nine-item scale adapted from Armsden and Greenberg (1987), with response options ranging from 1 = “almost never or never” to 4 = “almost always or always” (W1 α = .78; W2 α = .85).

Control variables

We controlled for mother’s education in years, mother’s age, mothers’ years in the U.S., and child gender (0 = boys, 1 = girls).

Analysis Strategy

Statistical models were fit to data using the Mplus program, Version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). We used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation given the presence of some missing data. FIML estimation has been found to be efficient and unbiased when data are missing at random and appears to be less biased than standard approaches (Arbuckle, 1996). To evaluate model fit, we used the standard chi-square index as well as several other indices that are less sensitive to sample size, including the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the comparative fit index (CFI). Analyses using a two-group model were performed to test whether the latent variables represented the same constructs for single- and two-parent families (Widaman & Reise, 1997).

Results

Correlations among latent variables were largely as expected (see Table 1). For example, economic pressure was associated with higher levels of internalizing symptoms (r = .37, p < .01). We next tested whether the parameters of our model varied as a function of household structure. Tests showed that our model functioned similarly in single-parent and two-parent families and so the two groups were combined into a single sample for further analyses.

Table 1.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal optimism W1 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 2. Economic pressure W1 | −.29** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 3. Internalizing symptoms W1 | −.38** | .37** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 4. Involved parenting W1 | .30** | −.23** | −.23** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 5. Nurturant parenting W1 | .11* | −.06 | −.01 | .24** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 6. Social competence W1 | .06 | −.21** | −.04 | .23** | .67** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 7. Social competence W2 | .07 | −.16** | −.03 | .26** | .35** | .76** | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. Household structure W1 | −.01 | .12** | .15** | −.02 | −.06 | −.01 | −.08 | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. Child gender (girls) W1 | .01 | .07 | −.02 | .11** | .11** | .11* | .14** | .01 | 1.00 | |||

| 10. Mothers’ age W1 | .02 | .04 | .02 | −.09* | .01 | .07 | .02 | .02 | .05 | 1.00 | ||

| 11. Mothers’ years in U.S. W1 | .08 | −.29** | −.09* | .15** | .06 | −.02 | −.08 | .14** | .05 | .28** | 1.00 | |

| 12. Mothers’ education W1 | .21** | −.32** | −.17** | .26** | .18** | .10* | .02 | .12* | .03 | −.04 | .38** | 1.00 |

p < .05.

p < .01 (two-tailed test).

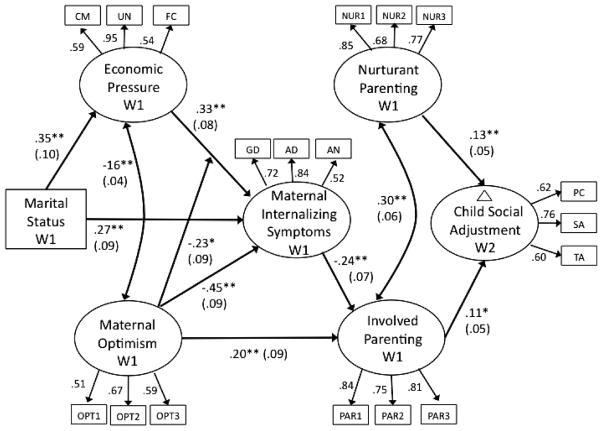

Results for the structural equation model are provided in Figure 1. Factor loadings of manifest indicators on latent variables were all statistically significant (p < .01), and relatively large, ranging from .51 to .95 in standardized metric. The restricted structural model had a significant statistical index of fit, χ2(260, N = 674) = 477, p < .01, as is common in large samples. However, the practical fit indices demonstrated very acceptable fit, with a RMSEA of .036, and CFI and TLI values of .946 and .935, respectively.

Figure 1.

Statistical model results with interaction effect. χ2(260, N = 674) = 477; CFI = .946; TLI = .935; RMSEA = .036. Only significant paths are shown. ** p < .01, * p < .05 (two-tailed test). Factor loadings (standardized) are all significant (p < .01). Standard errors are shown in parentheses. W1 = wave 1; W2 = wave 2; CM = cannot make ends meet; UN = unmet material needs; FC = financial cutbacks; OPT1 to OPT3 = dispositional optimism indicators; GD = general depression; AD = anhedonic depression; AN = anxiety; NUR1 to NUR3 = nurturant parenting indicators; PAR1 to PAR3 = involved parenting indicators; PC = peer competence; SA = school attachment; TA = teacher attachment. Δ = change in social adjustment (W2 controlling for W1).

Family Stress Model

As expected, marital status directly predicted economic pressure (b = .35, p < .01) and internalizing symptoms (b = .27, p < .01), with single mothers reporting higher levels relative to married mothers (see Figure 1). Economic pressure and maternal optimism were negatively correlated, and economic pressure positively predicted internalizing symptoms. The indirect effect of economic pressure on involved parenting through internalizing symptoms was moderate in magnitude, − 0.08 (SE = .03), and statistically significant based on the Sobel test, z = −2.64, p < .01. Mother’s internalizing symptoms negatively predicted involved parenting, but did not predict nurturant parenting. However, the indirect effect of internalizing symptoms on nurturant parenting through involved parenting was moderate in magnitude, +0.07 (SE = .025), and statistically significant based on the Sobel test, z = −2.83, p = .01.

Dispositional optimism

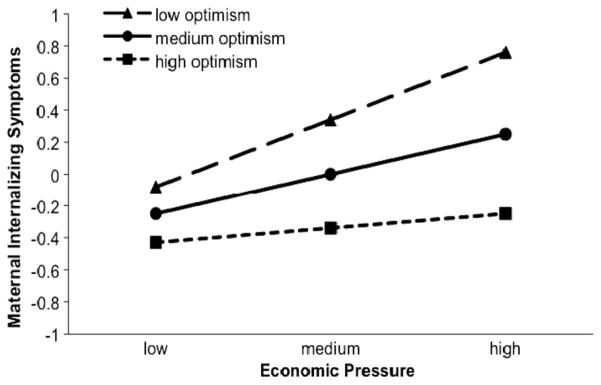

As hypothesized, dispositional optimism was associated with lower levels of internalizing symptoms and higher levels of involved parenting (see Figure 1). However, optimism did not predict nurturant parenting. Results also demonstrated that optimism moderated the relation between economic pressure and internalizing symptoms (see Figure 2). Specifically, the effect of economic pressure on internalizing symptoms was weak and nonsignificant (β = .08, z = 1.06, ns) when optimism was high, moderately positive (β = .25, z = 4.08, p < .001) at the mean level of optimism, and strongly positive (β = .42, z = 3.95, p < .001) when optimism was low.

Figure 2.

Interaction between economic pressure and maternal optimism, predicting mother’s internalizing symptoms (in standard score units). High and low optimism represent scores 1 standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively.

Parenting

As expected, involved parenting at W1 predicted change in child social competence from W1 to W2. Nurturant parenting at W1 also predicted change in social competence. Thus, positive parenting was associated with improvements in child social adjustment from W1 to W2. Additionally, the indirect effect of optimism on child social competence at W2 through involved parenting was small in magnitude, +0.02 (SE = .025), but statistically significant based on the Sobel test, z = 2.20, p = .027.

Discussion

Research with underrepresented populations, such as minority ethnic groups and single mothers, typically focuses on deficit models that highlight vulnerabilities within these families, but not their strengths or successes. In contrast, the present study examined whether dispositional optimism is associated with resilience to economic pressure in Mexican-origin families. Consistent with previous research, optimistic mothers tended to have fewer internalizing symptoms and exhibited higher levels of involved parenting behaviors. Maternal optimism also moderated the relation between economic pressure and internalizing symptoms. Specifically, economic pressure did not predict internalizing symptoms when mothers demonstrated high levels of optimism, supporting the idea that optimism is a psychological resource that buffers individuals against the adverse consequences of psychosocial stressors. Last, we found that mothers’ nurturant parenting and involved parenting predicted a small but positive change in child social adjustment from W1 to W2.

Contrary to our predictions, internalizing symptoms were not directly associated with nurturant parenting. Although some studies have found a negative significant path from internalizing symptoms to nurturant parenting (e.g., Mistry et al., 2002), other studies have found these associations to be nonsignificant (Conger et al., 2002; Taylor et al., 2010). However, overall our results were consistent with basic tenants of the FSM (Conger et al., 2010) and support prior studies evaluating the FSM in samples of Mexican-origin families (e.g., Parke et al., 2004). Most notably, our findings replicated previous research on African American single mothers (Taylor et al., 2010), and extended these prior findings to both single-parent and two-parent Mexican-origin families.

We also extended Taylor et al. (2010) by showing that our model of the family stress process holds equally well for both single-parent and two-parent families. Although the pathways were similar for the two groups, we did find that Mexican-origin single-parent families were more likely to experience economic pressure and internalizing symptoms compared with Mexican-origin two-parent families, which could indirectly place these families at higher risk for poor parenting behaviors and child adjustment. The findings are consistent with a large amount of literature showing that the environmental conditions too often experienced by single mothers, such as poverty and other demographic risks, are associated with emotional distress and other mental health problems. These stressors are, in turn, significant risk factors for uninvolved parenting and child maladjustment (Avison et al., 2007; Brown & Moran, 1997).

Consistent with our model, single-parent status did not directly predict parenting quality or child adjustment, but had only an indirect effect through economic pressure and internalizing problems. Furthermore, we failed to find any differences in child social adjustment as a direct result of family structure. This suggests that differences in parenting as the result of family structure are largely due to the higher levels of economic pressure and internalizing symptoms that single mothers experience. Inconsistent with our expectations, household structure was not associated with mothers’ optimism. However, as no study has examined whether optimism varies according to marital status, this finding should be replicated, especially with other ethnicities.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be noted. First, our findings were largely cross-sectional (other than child adjustment) and should be tested across time. However, these relations were tested longitudinally in a prior study (Taylor et al., 2010), and the current results are consistent with the prior findings. Second, we examined associations between parent optimism and family functioning only for mothers, and did not evaluate potential effects of fathers’ optimism or parenting. Although this was consistent with our questions of interest, which included studying single mothers as well as replicating prior findings with mothers, future studies should examine whether these associations are also evident for fathers. Third, although research suggests that optimists adjust better to stress and exhibit improved psychological well-being as a result of more effective coping strategies, this process was not directly tested.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide evidence that dispositional optimism may be a psychological characteristic that fosters resilience to adversity for mothers in both single- and two-parent families. Our findings also add to an abundant literature suggesting that interventions that reduce the effects of economic pressure would be of considerable benefit for Mexican-origin families. Although poverty has increased for all racial groups during the past decade, ethnic minorities remain disproportionately poor (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2010). Our study suggests optimism might provide an adaptive resource for coping with economic adversity. Accordingly, these results point to several avenues for prevention and intervention efforts. Although dispositional optimism is a relatively stable trait, research indicates that optimism is linked to effective coping strategies that can be fostered through psychosocial intervention such as cognitive–behavior therapy (Carver et al., 2010; Liossis, Shochet, Millear, & Biggs, 2009; Peterson, 2000). Improving coping strategies has the potential to help individuals manage stress and avoid compromising their mental health (Taylor & Stanton, 2007). Together, the current study and Taylor et al. (2010) suggest that dispositional optimism may be a useful psychological resource given the dual association with maternal internalizing problems (both a direct effect and through reducing the effect of economic pressure on internalizing symptoms). Also important, our findings provide additional evidence that optimism is positively associated with parenting behaviors that, in turn, are associated with positive child adjustment. Furthermore, dispositional optimism appears to function in a similar manner across ethnic and marital backgrounds.

These findings also point to other avenues of exploration with regard to dispositional optimism. First, little is known about the origins of optimism, or how we can prevent optimism from being thwarted (Peterson, 2000). Additional research on ethnic differences and how cultural beliefs and traditions moderate levels of optimism is also needed (Carver et al., 2010). Future research should also examine the mechanisms that characterize how optimists approach their environment so that interventions can be implemented that assist people in dealing more effectively with adversity in their lives (Carver et al., 2010). Last, research that examines how dispositional traits affect family contexts would make additional contributions to understanding pathways that lead to positive adjustment in families.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01DA017902).

Footnotes

Only nine families changed in household structure across waves, and as this variable was not associated with child adjustment at W2 it was removed from the analyses.

Contributor Information

Zoe E. Taylor, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of California, Davis

Keith F. Widaman, Department of Psychology, University of California, Davis

Richard W. Robins, Department of Psychology, University of California, Davis

Rachel Jochem, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of California, Davis.

Dawnte R. Early, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of California, Davis

Rand D. Conger, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of California, Davis

References

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:26–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:427– 454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avison WR, Ali J, Walters D. Family structure, stress, and psychological distress: A demonstration of the impact of differential exposure. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:301–317. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke AO, Macdermid SM, Coltrane SL, Parke R, Duffy S, Widaman KF. Family cohesion in the lives of Mexican American and European American parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1045–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00545.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Child Development. 1998;69:803– 816. doi: 10.2307/1132205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Kim S, Brown AC. Longitudinal pathways to competence and psychological adjustment among African-American children living in rural single-parent households. Child Development. 2002;73:1505–1516. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Moran P. Single-mothers, poverty and depression. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:21–33. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney J, Boyle M, Offord D, Racine Y. Stress, social support and depression in single and married mothers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38:442– 449. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0661-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso JB, Thompson S. Common themes of resilience among Latino immigrant families: A systematic review of the literature. Families in Society. 2010;91:257–265. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.4003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:879– 889. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC. Cultural influences on optimism and pessimism: Differences in Western and Eastern construals of the self. In: Chang EC, editor. Optimism & pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 257–280. (2001) [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Unpublished manuscript. 1995. The Mini Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (Mini-MASQ) [Google Scholar]

- Coffman DL, MacCallum RC. Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:235–259. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4002_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody G. Economic Pressure in African-American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ensel W, Lin N. The life stress paradigm and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:321–341. doi: 10.2307/2137101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL. Parents’ reactions to teacher’s practices of parent involvement. The Elementary School Journal. 1986;86:277–294. doi: 10.1086/461449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González P, González GM. Acculturation, optimism, and relatively fewer depression symptoms among Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans. Psychological Reports. 2008;103:566–576. doi: 10.2466/PR0.103.6.566-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelle LA, Busch EA, Warren JE. Explanatory style, dispositional optimism, and reported parental behavior. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1996;157:489– 499. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1996.9914881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Brody G, Armistead L. Positive parenting and child psychosocial adjustment in innercity, single-parent, African-American families: The role of maternal optimism. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:464– 481. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Brody G. Longitudinal pathways to psychological adjustment among black youth living in single-parent households. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:305–331. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishton JM, Widaman KF. Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1994;54:757–765. doi: 10.1177/0013164494054003022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N, Penney SJ, Boldt LJ. Parental personality as an inner resource that moderates the impact of ecological adversity on parenting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:136–150. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liossis PL, Shochet IM, Millear PM, Biggs H. The promoting adult resilience (PAR) program: The effectives of the second, shorter pilot of a workplace prevention program. Behaviour Change. 2009;26:97–112. doi: 10.1375/bech.26.2.97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, McLoyd VC. Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development. 2002;73:935–951. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide (Version 6) [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nes LS, Segerstrom SC. Dispositional optimism and coping: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:235–251. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njoku MG, Jason LA, Torres-Harding SR. The relationships among coping styles and fatigue in an ethnically diverse sample. Ethnicity and Health. 2005;10:263–278. doi: 10.1080/13557850500138613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novy DM, Nelson DV, Hetzel RD, Squitieri P, Kennington M. Coping with chronic pain: Sources of intrinsic and contextual variability. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;21:19–34. doi: 10.1023/A:1018711420797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, Widaman KF. Economic pressure, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child Development. 2004;75:1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C. The future of optimism. American Psychologist. 2000;55:44–55. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD, Spoth R, Simons RL. Evaluation of a social contextual model of delinquency: A cross-study replication. Child Development. 2002;73:175–195. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. Kin support and parenting practices among low-income African American mothers: Moderating effects of mothers’ psychological adjustment. Journal of Black Psychology. 2011;37:3–23. doi: 10.1177/0095798410372623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Stanton AL. Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:377– 401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ZE, Larsen-Rife D, Conger RD, Widaman KF, Cutrona CE. Life stress, maternal optimism, and adolescent competence in single-mother, African-American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:468–477. doi: 10.1037/a0019870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/income_wealth/cb11-157.html.

- Widaman KF, Reise SP. Exploring the measurement invariance of psychological instruments: Applications in the substance use domain. In: Bryant KJ, Windle M, West SG, editors. The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance abuse research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 281–324. [Google Scholar]