Abstract

In cardiac and skeletal muscle Ca2+ release from intracellular stores triggers actomyosin cross-bridge formation and the generation of contractile force. In the face of large fluctuations of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) that occur with contractile activity, myocytes are able to sense and respond to changes in workload and patterns of activation through calcium signaling pathways which modulate gene expression and cellular metabolism. Store-operated calcium influx has emerged as a mechanism by which calcium signaling pathways are activated in order to respond to the changing demands of the myocyte. Abnormalities of store-operated calcium influx may contribute to maladaptive muscle remodeling in multiple disease states. The importance of store-operated calcium influx in muscle is confirmed in mice lacking STIM1 which die perinatally and in patients with mutations on STIM1 or Orai1 who exhibit a myopathy exhibited by hypotonia. In this review, we consider the role of store-operated Ca2+ entry into skeletal muscle as a critical mediator of Ca2+ dependent gene expression and how alterations in Ca2+ influx may influence muscle development and disease.

Keywords: Skeletal muscle, Ca2+ entry, TRPC channels, SOCE, STIM1, Orai1, Musclular dystrophy, Hypotonia, Exercise, Gene expression

1. Introduction

Calcium signaling plays a fundamental role in many cellular processes including growth and differentiation, metabolism, and regulation of gene expression. Nowhere is this more clear than in skeletal muscle where Ca2+ release is required for muscle contraction through excitation contraction coupling (ECC). But changes in cytosolic Ca2+ in muscle can also be converted into biochemical changes through activation of signal transduction cascades that are require Ca2+/calmodulin for activation. Examples of these cascades include signaling through calmodulin kinases (CamK) or the Ca2+/calmodulin-activated serine-threonine phosphatase, calcineurin, where changes in Ca2+ can influence the phosphorylation state of key target proteins [1,2]. It is through these signaling cascades that Ca2+ can influence skeletal muscle development and differentiation. Here, we consider the role of Ca2+ entry into skeletal muscle as a critical mediator of Ca2+-dependent gene expression and how alterations in store-operated Ca2+ entry may influence muscle development and remodeling. Finally we discuss the role of abnormal store-operated calcium influx in the pathogenesis of myopathies: both in mouse models and in patients with combined immunodeficiency due to mutations in STIM1 or Orai1 (Figs. 1 and 2).

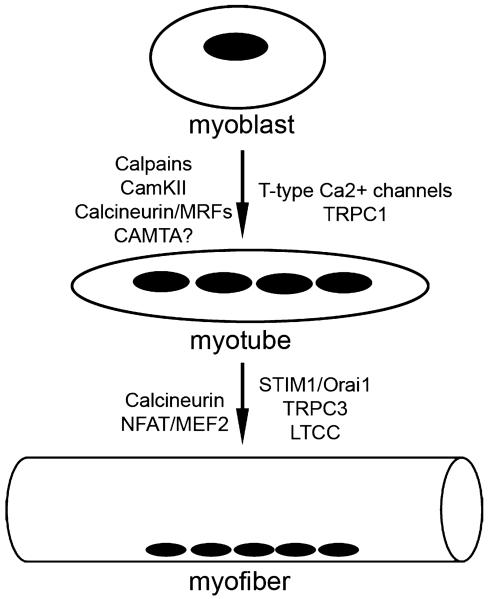

Fig. 1.

Calcium signaling proteins involved in the differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes and in the subsequent differentiation of myotubes into myofibers. Signaling proteins and transcription factors are listed to the left of the arrows. Ion channels and their regulatory proteins are listed on the right.

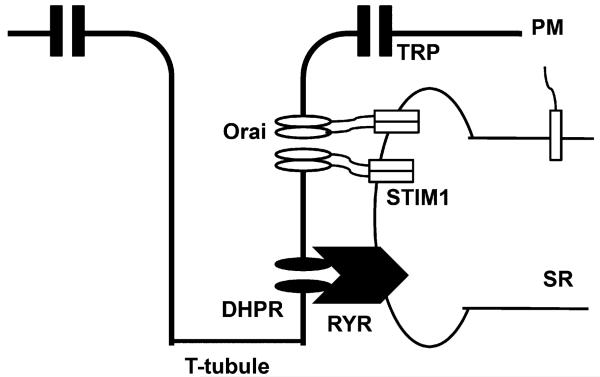

Fig. 2.

Model of SOCE in skeletal muscle. SOCE in skeletal muscle displays rapid kinetics compared to non-excitable cells. STIM1 localization may account for these kinetic differences. Electron micrographs of skeletal muscle from STIM1 gene trapped mice revealed STIM1 protein aggregates located in membranes of the terminal cisternae and the para-junctional SR. The junctional STIM1 pool is located near or complexed with Orai1 and can respond rapidly to store depletion. Parajunctional STIM1 is a reserve pool of STIM1 that is not complexed with Orai1, but is readily recruited to the junctional cleft in response to different patterns of muscle usage. Although recent studies have shown that STIM1 activation by store depletion suppresses L-type voltage-operated calcium (Cav1.2) channels, whether STIM1 plays a similar role in the regulation of L-type channels in skeletal muscle which expresses the Cav1.1 isoform is currently unknown.

2. Calcium signaling in myotube development

During muscle development and muscle regeneration, myoblasts proliferate and then undergo a highly ordered process of myogenic commitment in which they leave the cell cycle and express muscle specific proteins [3]. Myoblasts then migrate and align with each other, and ultimately undergo fusion with one another to form primary myotubes. Myoblasts then fuse with the primary myotubes generated in this manner to form secondary myotubes. A multitude of elements are critical for the process of myoblast fusion including membrane-associated proteins, signaling complexes, and extracellular/secreted molecules [4]. Calcium plays a critical role in multiple steps involved in myotube formation. Calcium activates intracellular cysteine proteases, calpains, which are required for cytoskeletal re-organization during migration and cell fusion [5]. Increased intracellular calcium also activates calcineurin, a serine-threonine phosphatase, involved in the downstream activation of MEF-2 and the NFAT family of transcription factors which have been shown to regulate myotube development [6-9]. Ca2+-calmodulin can also influence muscle specific gene expression through the activation of the CamKII pathway [10]. Here, CamKII can influence MEF2 signaling by altering the actions of class II histone deacetylases (HDAC) [11]. In addition CamKII can stimulate the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 (PGC-1), a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [2]. Finally, calmodulin can also influence the actions of a transcriptional coactivator called calmodulin binding transcriptional activator (CAMTA). CAMTAs are known to activate cardiac transcription through a mechanism that involves class II HDACs [12]. Interestingly, dCAM-TAs have been implicated in phototransduction of the drosophila eye [13]. Here, mutants of CAMTA signaling reveal a defect in the deactivation of rhodopsin. Given the critical importance of TRP channels in phototransduction, it is likely that Ca2+/calmodulin from TRP channels are required to activate CAMTA dependent transcription. Interestingly, several recent studies have demonstrated the importance of TRPC channels to striated muscle development, degeneration and performance [14-16]. It will be important to determine if CAMTAs have a role in the TRPC response of Ca2+ dependent gene expression in skeletal muscle. Furthermore a deeper knowledge of the specific pathways by which Ca2+ signaling influences gene expression in muscle will be important in our understanding of how these events occur during muscle development and are altered during the adaptation response to exercise or in the pathogenesis of myopathies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Myopathies associated with aberrant calcium entry.

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels have previously been shown to function in axonal pathfinding during neuronal development [17]. TRP channel activation by local growth factor concentrations allows for extension or retraction of axonal processes [18]. Recent studies have also implicated transient receptor potential channels in myotube development. We previously showed that overexpression of TRPC3 in C2C12 myotubes resulted in increased NFAT transactivation: a process involving activation of calcineurin by Ca2+ influx, dephosphorylation of NFAT by calcineurin, translocation of NFAT to the nucleus, and DNA binding by NFAT resulting in altered gene expression [15]. Similarly the scaffolding protein Homer, which has been shown to bind to multiple members of the TRP channel family, is expressed as part of the myogenic differentiation program and promotes myotube differentiation through modulation of calcium-dependent gene expression [19]. Homer enhanced calcium signaling via the calcineurin/NFAT pathway resulting in greater activation of a muscle-specific transcriptional program [20].

Evidence also suggests that TRPC1 may be a route for calcium influx required for calpain activation during myoblast migration and fusion. Migration of C2C12 myoblasts was inhibited by GsMTx-4 peptide, an inhibitor of mechanosensitive channels, and Z-Leu-Leu, an inhibitor of calpains. Knockdown of TRPC1 in C2C12 myoblasts resulted in decreased calpain activity, reduced cell migration, and a reduction in myotube fusion [21]. Growth factor stimulation resulted in increased calcium influx, calpain activity, and accelerated migration which was blocked by TRPC1 knockdown [21]. TRPC1 has also been shown to play a role in mechanotransduction during myotube development. TRPC1 knockdown inhibited stretch-activated calcium influx in C2C12 myoblasts in response to atomic force microscopic pulling and blocked stretch-activated current assessed by the whole-cell patch clamp technique [22]. TRPC1 activity was negatively regulated by cholesterol depletion, suggesting that TRPC1 was functionally assembled in lipid rafts, but enhanced by sphingosine-1-phosphate suggesting a role for stress fibers and the cytoskeleton in TRPC1 recruitment [22].

3. Store-operated calcium influx in skeletal muscle

It has long been assumed that Ca2+ entry into skeletal muscle fibers contributes little to calcium signaling. However recent evidence has challenged this notion. Three forms of Ca2+ entry have been characterized in skeletal myotubes and fibers: excitation coupled calcium entry (ECCE), stretch activated Ca2+ entry (SACE), and store operated calcium entry (SOCE) [23,24]. ECCE is activated in myotubes following prolonged membrane depolarization or pulse trains and is independent of the calcium stores. ECCE requires functioning L-type calcium channels (LTCC) and RYR1 channels. Although the molecular identity of the pore required for ECCE remains undefined, the skeletal L-type current mediated by DHPR has been shown to be a major (and perhaps sole) contributor to ECCE [25-27]. Supporting this concept is recent data showing that expression of the cardiac alpha(1C) subunit in myotubes lacking either DHPR or RYR1 does result in Ca2+ entry similar to that ascribed to ECCE [28]. Unlike SOCE, ECCE is unaffected by silencing of STIM1 or expression of a dominant negative Orai1 [29]. ECCE is altered in malignant hyperthermia (MH) and may contribute to the disordered calcium signaling found in muscle fibers of MH patients [30]. Stretch activated Ca2+ entry (SACE) has been described in skeletal muscle and is believed to underlie the abnormal Ca2+ entry in disease states such as muscular dystrophy [31-33].

SOCE, on the other hand, requires depletion of the internal stores and has been best characterized in non-excitable cells [34,35]. SOCE in skeletal muscle was described previously in myotubes [36], but it was not until the discovery of two important molecules, stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) and Orai1 in non-excitable cells, that the full importance of SOCE was recognized in muscle [37]. SOCE is likely to be important for refilling calcium stores necessary for normal metabolism and prevention of muscle weakness as well as contributing a signaling pool of calcium needed to modulate muscle specific gene expression. Key questions regarding Ca2+ entry in skeletal muscle include the identity of the molecular components of these pathways, the interrelationship of ECCE, SOCE and EC coupling, and finally, the relevance of these pathways to muscle performance and disease. It is important to point out that considerable overlap may exist between these different forms of Ca2+ entry. For example, recent studies have shown that STIM1 activation by store depletion strongly suppresses L-type voltage-operated calcium (Cav1.2) channels, expressed in brain, heart, and smooth muscle, while activating Orai channels [38,39]. Additional studies will be important to determine whether STIM1 plays a similar role in the regulation of L-type channels in skeletal muscle which expresses the Cav1.1 isoform. The role of STIM2, a STIM1 homolog, in skeletal muscle is also largely unknown. STIM2 has been shown to be activated by small changes in ER Ca2+ and has plays a regulatory role in the maintenance of basal cytosolic Ca2+ [40,41]. Recent work has shown that STIM2 silencing, similar to STIM1 silencing, reduced SOCE and inhibited differentiation of primary human myoblasts [42].

The concept of store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) was first introduced in 1986 when series of experiments suggested that depletion of internal Ca2+ stores controlled the extent of Ca2+ influx in nonexcitable cells [34]. This mechanism of Ca2+ entry served as a link between extracellular Ca2+ and intracellular Ca2+ stores. When the stores were full, no Ca2+ influx was detected, but when the stores were emptied, Ca2+ entry developed. This model, initially called capacitative calcium entry (CCE), was later supported by electrophysiological studies which established that depletion of Ca2+ stores activated a Ca2+ current in mast cells called the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ current, or ICRAC [43]. However, the channels that conduct these currents had remained unclear until very recently [44,45]. Since then, many other store-operated Ca2+ currents, each with different electrophysiological properties, have been discovered in diverse cell types. One unifying theme for these currents is that they are activated by any process that depletes internal Ca2+ stores, regardless of how the store is depleted. The final common pathway is store-operated calcium influx [46].

Skeletal muscle maintains a highly specialized calcium signaling apparatus that governs muscle contraction through the process of excitation contraction coupling [47]. It has been universally accepted that calcium release from internal stores (RYR1) in skeletal muscle provides the calcium needed to initiate and maintain muscle contraction. The L-type calcium channel (LTCC) located in the T-tubular membrane of a myofiber acts as a voltage sensor to activate calcium release from RYR1 stores in response to an action potential [47]. Local release of calcium from RYR1 channels activates the contractile complex over a short distance by providing large changes in Ca2+ in a small area. This enormous calcium transient is required to provide rapid and coordinated muscle contraction throughout the muscle fiber. The rapid kinetics of EC coupling involve not only an LTCC/RYR1 interaction, but also an efficient system to re-sequester calcium into internal stores. This re-sequestration is performed by the actions of the sarco/endoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase pump (SERCA1) and mitochondrial calcium buffering and is critical for relaxation of skeletal muscle fibers [48]. SERCA1 can refill calcium stores faster than the other SERCA isoforms: SERCA2a and SERCA3 [49]. The kinetics of SERCA1, which is found only in skeletal muscle, may provide an important difference between SOCE in muscle compared to that observed in T-cells. Other plasma membrane calcium pumps such as the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) are known to exist in the sarcolemma and work to rapidly lower cytosolic Ca2+ levels in order to relax the myofiber [50-52]. The cooperation of each member of the calcium signaling cascade is important to produce the rapid calcium transient necessary for muscle contraction.

Calcium entry into a myofiber from the extracellular space has been largely overlooked as a mechanism of store refilling. However, a recent challenge to the long held notion that muscle contraction can continue in the absence of external calcium was offered by studies demonstrating that repeated stimulation of isolated muscle fibers without external calcium results in the depletion of internal stores and loss of EC coupling [53]. As a consequence of store depletion, muscles fatigue and lose the ability to generate force. These effects are reversed by adding calcium to the perfusion bath [54,55]. This mechanism, demonstrated in myogenic cell lines, primary embryonic myotubes, and isolated single myofibers, suggests an unrecognized but important role for SOCE in normal skeletal muscle function. However, critical details such as the kinetics of SOCE activation, the extent of store depletion required to activate SOCE, the SOCE channel involved in the refilling, and even the functional role of SOCE in skeletal muscle remain to be defined [56]. Elaborate buffering, specialized release (RYR1), and Ca2+ reuptake (SERCA1) provide for efficient cycling of Ca2+ during EC coupling making it difficult to understand the functional role of SOCE in muscle fibers. Despite the growing number of studies measuring SOCE in myofibers and characterizing important features of this signaling, others have offered proof in opposition to the SOC hypothesis in muscle [57].

In earlier studies involving isolated single fibers a prolonged period of time (five minutes) was required to deplete internal stores and activate SOCE following sustained electrical stimulation [53]. More recent studies, including our own, suggest that SOCE in muscle is a more rapid process occurring on the order of seconds [58,37]. Because skeletal muscle maintains a highly specialized Ca2+ store that is located in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, we considered that STIM1 localization may account for the kinetic differences between muscle fibers and non-excitable cells. We have used a variety of techniques to study STIM1 localization in skeletal muscle. In particular, electron micrographs revealed STIM1 protein aggregates located in membranes of terminal cisternae and the para-junctional SR: these aggregates were observed in the absence of store depletion. This was consistent with immunostaining which revealed partial co-localization of STIM1 and RYR1 [37]. The terminal cisternae are a specialized SR domain containing RYR1 and that abut the T-tubular plasma membrane system to establish junctional clefts. We have considered a model in which STIM1 resides in two pools. The junctional STIM1 pool is located near or complexed with Orai1 and can therefore respond rapidly to store depletion. In contrast parajunctional STIM1 is a reserve pool of STIM1 that is not complexed with Orai1, but is readily recruited to the junctional cleft in response to different patterns of muscle usage. Additional factors that may account for the rapid kinetics of SOCE include post-translational modification of STIM1 and the local sensing of Ca2+ stores. The N-terminal domain of STIM1 resides in the ER/SR lumen where it senses SR Ca2+ store content and then engages in activation of the SOC channels. Interestingly, the specific cysteine residues located in this N-terminus of STIM1 are subjected to S-glutathionylation which can influence SOCE [59]. It is possible that differences exist in the SR/ER redox environment of skeletal muscle compared to non-excitable cells which may account for the different kinetic properties. Along the same lines, several serines and threonines located in the C-terminus of STIM1 have been shown to be modified by phosphorylation [60,61]. It is possible that STIM1 is differentially phosphorylated in skeletal muscle and that this could play a role in its regulation. Phosphorylation of serine residues of STIM1 results in inhibition of store-operated calcium entry during mitosis in HeLa cells [62]. While in another study, mutational analysis failed to show a role for phosphorylation in the inhibition of STIM1 puncta formation during meiosis in Xenopus oocytes, although mutations of the specific serine residues that regulated SOCE during mitosis were not directly tested [63].

While the electrophysiologic properties of SOCE currents have been well documented, the molecular components of the underlying channels and the mechanism by which a cell senses store depletion and activates SOCE had remained elusive for many years. In 2005, independent groups used RNA interference (RNAi)-based screens to identify STIM1 as a key component of SOCE [64,65]. STIM1 is a single-pass, transmembrane phosphoprotein that was initially cloned from stromal cells involved in pre-B cell differentiation and implicated as a tumor suppressor for rhabdoid tumors and rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines [61]. Two homologues of Drosophila STIM (dSTIM) have been identified in vertebrates, STIM1 and STIM2. The 3D structure of STIM1 has been predicted based on the amino acid sequence and includes an EF-hand domain, a sterile-α-motif (SAM) domain, a transmembrane-spanning region, coiled-coil regions, and proline-rich N terminus [35]. The EF-hand domain of STIM1 has a high affinity for calcium (200–600 uM range) and is located in the lumen of the ER where it senses changes in calcium store content [66]. The SAM domain of STIM1 is a protein–protein interaction domain that is also located in the lumen of the ER, a location not previously described for other SAM domain-containing proteins [67]. The cytosolic coiled coil domains are located at the C-terminus and are important for oligomerization and punctae formation that is required for activation of SOC channels [68].

Recent studies of STIM1 gain of function/loss of function indicate that STIM1 mediates SOCE [69]. Specifically, enhanced calcium influx is associated with STIM1 overexpression in RBL cells, human Jurkat T cells, HeLa cells and human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells [69-72]. In contrast, diminished ICRAC was observed with RNAi-mediated knockdown of dSTIM in Drosophila S2 cells and STIM1 in human T cells, RBL cells, and HeLa cells [71,72]. The proposed function for STIM1 as the calcium sensor was elucidated from studies of a mutation in the EF-hand domain of STIM1 that abolishes STIM1’s calcium binding capacity [64,65]. Results of these studies indicated that STIM1 mutants were constitutively active, as calcium influx continued through the ICRAC channels without store depletion. These data support a model in which changes in ER calcium content are sensed by the EF hands of STIM1 leading to a series of events that activate SOCE.

The mechanism by which STIM1 triggers SOCE is still under investigation. It appears that a series of events are initiated by calcium store depletion and lead to STIM1 oligomerization, punctae formation, plasma membrane targeting and SOC channel activation [73,74]. Using fluorescent protein tagged STIM1, multiple groups have found that the majority of STIM1 is located in the ER under resting conditions. Upon store depletion, STIM1 aggregates into clusters, or punctae, which are enriched at junctional sites of the ER and plasma membrane. Here, the literature diverges as to whether the punctae are inserted into the plasma membrane or remain in the ER that is close to the plasma membrane (also known as junctional ER) [73,75]. Reconciliation of these differences may reflect different experimental approaches and technical issues [74,76]. In both cases however, the importance of the STIM1 assembly near the plasma membrane is required for activation of SOCE. Recent data using electron microscopy to detect horseradish peroxidase (HRP) labeled STIM1 showed that following store depletion, STIM1 accumulates within 10–25 nm of the plasma membrane [75]. Another recent study utilizing FRET revealed a series of four steps in the activation of SOCE [73]. In the first step, ER calcium store content is reduced regardless of mechanism (agonist-mediated PLC activation or SERCA blockade). Second, store depletion precipitated a physical interaction between STIM1 molecules indicated by increased FRET signal. The STIM1–STIM1 interaction required a functional EF hand, supporting the idea that the EF hand of STIM1 senses changes in ER calcium content [73]. Third, STIM1 multimers assemble into punctae using the C-terminal polybasic region of STIM1 residing in the cytosol. STIM1–STIM1 FRET was identical between WT and STIM1 C-terminal mutants indicating that calcium sensing and oligomerization were intact, however C-terminal mutants of STIM1 failed to assemble into punctae. These results divide the STIM1 molecule into two functional components: N-terminal calcium sensing and oligomerization and C-terminal punctae formation and ER-plasma membrane targeting. These steps are required for the fourth and final step: store-operated channel activation and calcium entry [73].

The identity of calcium entry channels which respond to STIM1 remain a matter of some debate. At least three candidates have been offered as the STIM1-dependent SOCE channels: Orai channels, TRPC channels, and arachidonic acid-regulated (ARC) channels [68,71,72,77]. Simultaneously with the identification of STIM1, Orai1 was identified in siRNA-based screens for mediators of SOCE and was found to be mutated in immunodeficient patients that lacked SOCE [44,45,71]. The Orai family of calcium entry channels includes three members and bares little resemblance to other ion channel families. Orai proteins are predicted to have four transmembrane spanning regions and share structural similarities with the gamma subunit of the L-type calcium channel (CaV gamma), transmembrane AMP receptor proteins and claudins [78]. Two studies analyzing mutations in the membrane spanning region of Orai1 demonstrated an altered ion selectivity of ICRAC, indicating that Orai proteins represent the pore for ICRAC [72,79,80].

TRPC channels interact with STIM1 and are likely to be the putative SOCE channel in platelets, as well as glandular and pancreatic acinar epithelial cells [81,82]. STIM1 immunoprecipitates with TRPC1, and silencing STIM1 greatly reduced TRPC1 currents whereas overexpression of STIM1 enhanced TRPC1 mediated SOCE currents and calcium influx [83]. According to the Muallem group’s recent studies, the effects of STIM1 gene silencing on TRPC3/C6 appear to be indirect through a TRPC1/STIM1 interaction [83]. In a related study, Orai1 was shown to interact with TRPC3 and TRPC6 as a subunit in a manner similar to the minK interaction with potassium channels [81]. Overexpressing Orai enhanced SOCE in cells overexpressing TRPC3 and TRPC6, while no effect was observed in cells expressing an irrelevant receptor. These data were interpreted as evidence that Orai1 is the beta-subunit of the store operative TRPC channel. Finally, recent work suggests that the pool of STIM1 expressed on the cell surface is not involved with SOCE but instead regulates the arachidonic acid-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels: receptor-activated Ca2+ channels distinct from store-operated channels that have been recently shown to consist of a pentameric assembly of Orai1 and Orai3 subunits [84,85]. Thus, Orai1 and STIM1 are required for both SOCE and arachidonic acid activated Ca2+ influx. Our previous work, as well the work of many others, demonstrate that TRPC channels are expressed and functional in skeletal muscle fibers, where they likely influence SOCE in exercised muscle [15]. It is also important to point out that patients with mutations in Orai1 also manifest a skeletal myopathy [86]. Whether STIM1 influences SOCE through TRP, Orai or both are important questions that remain unresolved particularly in skeletal muscle.

4. Calcium-dependent gene expression in skeletal muscle remodeling

In adult skeletal muscle, the mass of individual myofibers and of muscle tissues can be regulated by increases in contractile load resulting in muscle hypertrophy and increased strength. Skeletal muscle can also undergo profound remodeling in response to changing patterns of neural activation that control calcium-dependent gene expression and establish subtypes of muscle fibers [87]. Fast, glycolytic fibers (type IIb) are adapted for rapid generation of contractile force but fatigue rapidly, while slow, oxidative fibers (type I) are capable of repetitive contractile activity and are resistant to fatigue. Between the fast, glycolytic and slow, oxidative ends of the spectrum of muscle fibers lie several intermediate forms (IIa, IIx). The diversity of myofibers is based on the differential expression of genes that encode different isoforms of contractile proteins, signaling proteins, regulators of metabolism, and cytoskeletal elements [88].

The signals that allow myofibers to sense and respond to changes in work activity with alterations in gene expression include mechanical stresses sensed by the underlying cytoskeleton to activate signaling pathways; release of extracellular signaling molecules which act in an paracrine or autocrine manner through activation of receptors at the cell surface; changes in intracellular metabolites sensed by signaling proteins; and changes in the calcium signals themselves as the result of altered activity [89]. While it has been well established that changes in the frequency and amplitude of intracellular calcium transients that result from neural or hormonal activation control the rate or force of muscle contraction, it has only been recently recognized that these changes in calcium signals also control the changes in gene expression that regulate the contractile and metabolic properties of muscle [90]. Recent descriptions of the microdomains of calcium signaling within myocytes may explain how changes in calcium signals are able to activate downstream pathways in the setting of large fluctuations of cytosolic calcium that occur with contractile activity [89].

Signaling pathways responsible for decoding calcium signals include the Ca2+-calmodulin serine-threonine phosphatase calcineurin, Ca2+-calmodulin protein kinases (CamK), and transcriptions factors of the NFAT, MEF2, and PGC-1 families [1,2,91]. Transgenic mice have been engineered to express a lacZ reporter gene under the control of multimerized binding sites for either NFAT or MEF2 [91]. Studies of these reporter mice indicate that both transcription factors are involved in muscle development during embryonic development. In sedentary adult mice, however, no detectable transactivation of either NFAT or MEF2 indicators is observed. Both NFAT and MEF2 indicators are activated by an increased frequency of muscle contractions, either by spontaneous treadmill running or electrical pacing of a motor nerve [15]. Muscle specific overexpression of constitutively active calcineurin resulted in remodeling with an increase in oxidative fibers but no increase in fiber hypertrophy [92]. Muscle specific overexpression of the calcineurin-interacting protein, RCAN1, resulted in replacement of the slow myosin heavy chain MyHC-1 with a fast isoform, MyHC-2A in adult mouse soleus muscle and increased susceptibility to fatigue. MyHC-1 expression in soleus muscle of embryos and early neonates was normal [93]. These results demonstrated that the development of slow fibers is independent of calcineurin, while the maintenance of the slow-fiber phenotype in the adult requires calcineurin activity. Forced overexpression of a constitutively active CaMKIV in skeletal muscle revealed an unexpected link to the transcription factor PGC-1, a co-activator of PPAR-gamma target genes and master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [2]. Skeletal muscles from these transgenic mice showed augmented mitochondrial biogenesis, up-regulation of mitochondrial enzymes involved in fatty acid metabolism and electron transport, and reduced susceptibility to fatigue during repetitive contractions. Activated CaMKIV induced expression of PGC-1 in vivo, and activated the PGC-1 gene promoter in cultured myocytes. Thus, mitochondrial biogenesis is regulated by a calcium signaling pathway in skeletal muscle [2].

We have previously shown that calcineurin/NFAT signaling is regulated by neuromuscular activity and that calcium influx mediated by the TRPC3 channel enhances NFAT activity in cultured myotubes. In addition, expression of TRPC3 in skeletal muscle is itself upregulated by neuromuscular activity in a calcineurin-dependent manner [15]. TRPC3 represents an example of how a protein involved in upstream regulation of calcineurin/NFAT signaling may itself be regulated by calcineurin/NFAT signaling, thereby stabilizing the remodeled state. Similarly, myotubes overexpressing a wildtype or a constitutively active form of STIM1 displayed an increase (2.5 and 4.5 fold respectively) in basal NFAT transactivation when compared to control myotubes, and myotubes in which STIM1 expression was silenced exhibited a decrease in basal NFAT transactivation [37]. Calcineurin/NFAT signaling controls morphogenetic events of muscle formation, which occur around embryonic day 15.5. STIM1 mRNA expression increases in the embryo starting at E7.5 through E15.5: concomitant with this period are morphogenic events that are controlled by NFAT transactivation. Thus, results of these in vitro and in vivo studies indicate STIM1 plays a role in calcium-dependent gene expression in skeletal muscle [37].

5. Calcium influx and skeletal myopathies

A role for SOCE in human disease was confirmed in recent studies of patients with combined immunodeficiency. Mutations in Orai1 have been identified in patients from multiple unrelated families suffering from combined immunodeficiency [44,86,94,95]. The identification of a missense mutation (R91W) in the first transmembrane domain of Orai1 in one of these families, combined with a genome-wide RNAi screen in Drosophila S2 cells, led to the initial identification of Orai1 as a CRAC channel subunit [44]. After identification of Orai1 as the pore-forming subunit of the CRAC channel, unique mutations in Orai1 were identified in two additional unrelated families with combined immunodeficiency in whom defects in SOCE in T cells had previously been described [95,96]. A myopathy in patients with Orai1 mutations is noticeable soon after birth with symptoms of global hypotonia and respiratory muscle weakness. The results of a muscle biopsy from a patient with a R91W mutation in Orai1 revealed atrophy of type II fibers [86,96]. More recently, a mutation in STIM1 has been identified in three siblings with a syndrome of immunodeficiency, hepatosplenomegaly, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, abnormal dental enamel, and muscular hypotonia [97]. Homozygous nonsense mutations in STIM1 (E136X) were identified in two of these siblings. All three siblings exhibited a nonprogressive muscular hypotonia. While the older affected siblings succumbed to complications of hematopoetic stem cell transplantation and infection respectively, the youngest affected sibling survived hematopoetic stem cell transplantation with resolution of his immunodeficiency but continues to exhibit muscular hypotonia [97]. This suggests that the myopathy exhibited by these siblings is not secondary to autoimmunity. In summary, the clinical phenotypes of patients deficient in STIM1 or Orai1 are remarkably similar and consist of immune deficiency, autoimmunity, and myopathy. Mouse models with tissue specific deletion of STIM1 and Orai1 are likely to provide further mechanistic insight to this human genetic disease.

Increased calcium influx has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy (DMD). This abnormal calcium influx has been thought to be due to increased activation of either mechanosensitive channels (MSCs) or SOCE channels. Disruption of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex (DGC), which links the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane, is a hallmark of multiple forms of muscular dystrophy and has been associated with abnormal MSC activity leading to increased calcium influx [33]. Streptomycin, an inhibitor of MSCs has been shown to prevent the rise of resting intracellular calcium and partially prevented the decline of tetanic Ca2+ and force seen after stretched eccentric contractions in mdx muscle fibers which lack dystrophin and serve as a model of DMD. Mdx mice treated with streptomycin systemically also showed a significant decrease in frequency of central nuclei compared to controls [98].

Using measurements of patch capacitance and geometry, Suchyna and Sachs showed that the higher levels of MSC activity in mdx mice, compared to wild-type mice, are linked to cortical membrane mechanics rather than to differences in channel gating [99]. Patches from mdx mice were found to be strongly curved towards the pipette tip by actin pulling perpendicular to the membrane, producing substantial tension that can activate MSCs in the absence of overt stimulation. The inward curvature of patches from mdx mice was eliminated by actin inhibitors [99]. Hayakawa et al. recently demonstrated that direct mechanical stretching of an actin stress fiber using optical tweezers can activate MSCs in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells [100]. Then by using high-speed total internal reflection microscopy, spots of Ca2+ influx were visualized across individual MSCs distributed near focal adhesions providing direct evidence that the cytoskeleton works as a force-transmitter to activate MSCs [100]. The molecular identity of MSCs in currently a focus of much ongoing effort. Using expression profiling and silencing of candidate genes, Coste et al. identified Piezo1 and 2, members of a family of broadly expressed multipass transmembrane proteins with homologs in invertebrates, plants, and protozoa, as being required for MSC activity in Neuro2a cells [101]. It will be interesting to see if Piezos serve a similar role in skeletal muscle and if modulation of Piezo expression has a protective role in DMD.

Using proteomic techniques, TRPC1 was previously identified as being required for MSC activity in frog oocytes [102]. Since that time, however, an increase in MSC activity was not shown with expression of TRPC1 in heterologous cells which may be due to problems with channel trafficking in heterologous cells or lack of important accessory proteins in these cells [103]. Evidence also suggests that stretch-activation of TRP channels may not be a direct effect but rather an indirect effect of agonist-independent activation of signaling through G protein coupled receptors and phospholipase C [104]. A role for TRP channels has been described in Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. Vandebrouck et al. have shown a physical association between TRPC1 and dystrophin as well as alpha1-syntrophin, both components of the DGC, and repression of TRPC1 expression with antisense oligonucleotides has been shown to decrease single-channel activity in mdx myofibers [14,105]. TRPC1, caveolin-3 and Src-kinase protein levels are increased in mdx muscle. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are elevated in DMD, increased Src activity and enhanced Ca2+ influx in myoblasts co-expressing TRPC1 and caveolin-3.

Because the scaffolding protein Homer 1 has been implicated in TRP channel regulation, we hypothesized that Homer proteins play a significant role in skeletal muscle function [19]. Mice lacking Homer 1 exhibited a myopathy characterized by decreased muscle fiber cross-sectional area and decreased skeletal muscle force generation [106]. Homer 1 knockout myotubes displayed spontaneous cation influx and increased basal current density which was blocked by GsMTx-4 peptide, an inhibitor of MSCs. The spontaneous cation influx in Homer 1 knockout myotubes was blocked by re-expression of Homer 1b, but not Homer 1a, and by gene silencing of TRPC1. Moreover, diminished Homer 1 expression in mouse models of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy suggests that loss of Homer 1 scaffolding of TRP channels may contribute to the increased MSC activity observed in mdx myofibers [106]. These findings provide direct evidence that Homer 1 functions as an important scaffold for TRP channels and regulates mechanotransduction in skeletal muscle.

Ducret et al. characterized SOCE channels (SOCs) and MSCs in adult murine flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles [107]. Measurements of single-channel activity using cell-attached patches after stimulation with thapsigargin revealed that SOCs were voltage independent, had a unitary conductance of 7–8 pS (110 mM Ca2+ in pipet) and their open probability increased by a factor of 2.8 when the SR store was depleted by thapsigargin. Applying a negative pressure to the patch electrode increased the open probability of MSCs but had no effect on their conductance or reversal potential which was similar to that measured for SOCs. SOCs and MSCs were similarly blocked by Gd3+ and GsMTx4 toxin, and activated by IGF-1 suggesting that SOCs and MSCs may share common components [107]. Boittin et al. reported increased SOCE in flexor digitorum brevis muscle fibers isolated from mdx mice in response to store depletion with thapsigargin [108]. This exaggerated SOCE was blocked by BTP2, Gd3+, and bromoenol lactone (BEL), an inhibitor of Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2. Moreover, expression of Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 was found to be upregulated in muscle from mdx mice suggesting a role for signaling though this enzyme in the abnormal SOCE observed in muscle fibers from mdx mice [108]. A clearer role for SOCE in the pathogenesis of muscular dystrophy may come from generating mdx mice which are haploinsufficient for STIM1. At the current time it is unclear if the increased SOCE noted in mdx myofibers contributes to the dystrophic process or if the SOCE is compensatory in some way.

Malignant hyperthermia is a severe, life-threatening condition in which mutations in ryr1 result in direct activation of the ryanodine receptor by halogenated volatile anesthetics resulting in calcium release from the channel, muscle contracture, and a life-threatening increase in core body temperature. Mutations in ryr1 are also associated with central core disease (CCD) and the related diseases nemaline myopathy and centronuclear myopathy [109]. Patients with central core disease suffer from symptoms of muscle weakness at a young age, and unlike MH, these symptoms are present in the absence of external factors such as anesthetics. Pathologically CCD is characterized by cores of metabolically inactive tissue at the center of muscle fibers which lack mitochondria. CCD and MH show considerable clinical overlap as patients with CCD are also at increased risk for the development of MH [109]. Signs and symptoms of MH include the acute onset of muscular rigidity after administration of anesthesia with a rapid increase in body temperature associated with a hypercatabolic state. The increased metabolic demands as a result of elevated Ca2+ and persistent contraction lead to ATP depletion, acidosis, and often rhabdomyolysis. It was previously assumed that the persistent rise in cytoplasmic Ca2+ seen in malignant hyperthermia was the result of Ca2+ release from the SR. Recent work, however, suggests that SOCE may contribute to the sustained increase in intracellular calcium seen in malignant hyperthermia. Duke et al. provide evidence that SOCE is activated in myofibers from patients with MH [110]. Biopsies of vastus medialis muscle were obtained from patients undergoing testing for MH susceptibility. Single fibers were mechanically skinned and changes in Ca2+ both within the cell and within the resealed t-tubular system were simultaneously measured in response to halothane stimulation. Halothane treatment resulted in SR Ca2+ release and Ca2+ depletion in the in the t-tubular system in fibers isolated from patients with MH but not in controls, consistent with activation of SOCE in MH. SOCE was blocked in MH muscle fibers by application of a STIM1 antibody to the t-tubular system but not by application of a heat denatured STIM1 antibody [110].

6. Summary

Store-operated calcium influx in skeletal muscle provides a pool of calcium necessary for signaling and activation of Ca2+-dependent gene expression in muscle development and remodeling. The importance of SOCE in an excitable tissue such as skeletal muscle, although previously underappreciated, has recently been highlighted by data from mouse models and patients with immunodeficiency. Loss of STIM1-dependent SOCE in mice results in a profound myopathy and perinatal mortality, while a myopathy in patients with immunodeficiency due to mutations in STIM1 or Orai1 is manfest as hypotonia. Abnormalities in store operated Ca2+ influx are observed in pathologic states such as muscular dystrophy and malignant hyperthermia. The mechanism by which abnormal SOCE contributes to the pathogenesis of these disorders is unclear but likely includes activation of maladaptive Ca2+ signaling pathways leading to disorders of metabolism, abnormal protein handling, and adverse remodeling.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the following grants: NIH awards (K08-HL071841 to J.A.S. and R01-HL0934470 to P.B.R), an H.H.M.I. Physician-Scientist Early Career Award to J.A.S., and MDA Research Grants to J.A.S. and P.B.R.

References

- [1].Chin ER, et al. A calcineurin-dependent transcriptional pathway controls skeletal muscle fiber type. Genes Dev. 1998;12(16):2499–2509. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wu H, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle by CaMK. Science. 2002;296(5566):349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.1071163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jansen KM, Pavlath GK. Molecular control of mammalian myoblast fusion. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;475:115–133. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-250-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Horsley V, et al. IL-4 acts as a myoblast recruitment factor during mammalian muscle growth. Cell. 2003;113(4):483–494. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00319-2. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Barnoy S, Glaser T, Kosower NS. Calpain and calpastatin in myoblast differentiation and fusion: effects of inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1358(2):181–188. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Friday BB, Horsley V, Pavlath GK. Calcineurin activity is required for the initiation of skeletal muscle differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149(3):657–666. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Friday BB, et al. Calcineurin initiates skeletal muscle differentiation by activating MEF2 and MyoD. Differentiation. 2003;71(3):217–227. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.710303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].O’Connor RS, et al. A combinatorial role for NFAT5 in both myoblast migration and differentiation during skeletal muscle myogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 1):149–159. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pavlath GK, Horsley V. Cell fusion in skeletal muscle—central role of NFATC2 in regulating muscle cell size. Cell Cycle. 2003;2(5):420–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Passier R, et al. CaM kinase signaling induces cardiac hypertrophy and activates the MEF2 transcription factor in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105(10):1395–1406. doi: 10.1172/JCI8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shen T, et al. Parallel mechanisms for resting nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling and activity dependent translocation provide dual control of transcriptional regulators HDAC and NFAT in skeletal muscle fiber type plasticity. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2006;27(5-7):405–411. doi: 10.1007/s10974-006-9080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Song K, et al. The transcriptional coactivator CAMTA2 stimulates cardiac growth by opposing class II histone deacetylases. Cell. 2006;125(3):453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Han J, et al. The fly CAMTA transcription factor potentiates deactivation of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled light receptor. Cell. 2006;127(4):847–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vandebrouck C, et al. Involvement of TRPC in the abnormal calcium influx observed in dystrophic (mdx) mouse skeletal muscle fibers. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158(6):1089–1096. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rosenberg P, et al. TRPC3 channels confer cellular memory of recent neuromuscular activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101(25):9387–9392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308179101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zanou N, et al. Role of TRPC1 channel in skeletal muscle function. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00241.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li Y, et al. Essential role of TRPC channels in the guidance of nerve growth cones by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Nature. 2005;434(7035):894–898. doi: 10.1038/nature03477. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bezzerides VJ, et al. Rapid vesicular translocation and insertion of TRP channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6(8):709–720. doi: 10.1038/ncb1150. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yuan JP, et al. Homer binds TRPC family channels and is required for gating of TRPC1 by IP3 receptors. Cell. 2003;114(6):777–789. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00716-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stiber JA, et al. Homer modulates NFAT-dependent signaling during muscle differentiation. Dev. Biol. 2005;287(2):213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Louis M, et al. TRPC1 regulates skeletal myoblast migration and differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 23):3951–3959. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Formigli L, et al. Regulation of transient receptor potential canonical channel 1 (TRPC1) by sphingosine 1-phosphate in C2C12 myoblasts and its relevance for a role of mechanotransduction in skeletal muscle differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 9):1322–1333. doi: 10.1242/jcs.035402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cherednichenko G, et al. Conformational activation of Ca2+ entry by depolarization of skeletal myotubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101(44):15793–15798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403485101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Williams RS, Rosenberg P. Calcium-dependent gene regulation in myocyte hypertrophy and remodeling. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2002;LXVII:1–5. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2002.67.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hurne AM, et al. Ryanodine receptor type 1 (RyR1) mutations C4958S and C4961S reveal excitation-coupled calcium entry (ECCE) is independent of sarcoplasmic reticulum store depletion. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280(44):36994–37004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bannister RA, Grabner M, Beam KG. The alpha(1S) III-IV loop influences 1,4-dihydropyridine receptor gating but is not directly involved in excitation-contraction coupling interactions with the type 1 ryanodine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283(34):23217–23223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804312200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bannister RA, Pessah IN, Beam KG. The skeletal L-type Ca(2+) current is a major contributor to excitation-coupled Ca(2+) entry. J. Gen. Physiol. 2009;133(1):79–91. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bannister RA, Beam KG. The cardiac alpha(1C) subunit can support excitation-triggered Ca2+ entry in dysgenic and dyspedic myotubes. Channels (Austin) 2009;3(4):268–273. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.4.9342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lyfenko AD, Dirksen RT. Differential dependence of store-operated and excitation-coupled Ca2+ entry in skeletal muscle on STIM1 and Orai1. J. Physiol. 2008;586(Pt 20):4815–4824. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cherednichenko G, et al. Enhanced excitation-coupled calcium entry in myotubes expressing malignant hyperthermia mutation R163C is attenuated by dantrolene. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;73(4):1203–1212. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.043299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Franco A, Jr., Lansman JB. Calcium entry through stretch-inactivated ion channels in mdx myotubes. Nature. 1990;344(6267):670–673. doi: 10.1038/344670a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yeung EW, et al. Effects of stretch-activated channel blockers on [Ca2+]i and muscle damage in the mdx mouse. J. Physiol. 2005;562(Pt 2):367–380. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lansman JB, Franco-Obregon A. Mechanosensitive ion channels in skeletal muscle: a link in the membrane pathology of muscular dystrophy. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006;33(7):649–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Putney JW., Jr. A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 1986;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Putney JW., Jr. New molecular players in capacitative Ca2+ entry. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 12):1959–1965. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hopf FW, et al. A capacitative calcium current in cultured skeletal muscle cells is mediated by the calcium-specific leak channel and inhibited by dihydropyridine compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271(37):22358–22367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Stiber J, et al. STIM1 signalling controls store-operated calcium entry required for development and contractile function in skeletal muscle. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10(6):688–697. doi: 10.1038/ncb1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang Y, et al. The calcium store sensor: STIM1, reciprocally controls Orai and CaV1.2 channels. Science. 2010;330(6000):105–109. doi: 10.1126/science.1191086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Park CY, Shcheglovitov A, Dolmetsch R. The CRAC channel activator STIM1 binds and inhibits L-type voltage-gated calcium channels. Science. 2010;330(6000):101–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1191027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Brandman O, et al. STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell. 2007;131(7):1327–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Parvez S, et al. STIM2 protein mediates distinct store-dependent and store-independent modes of CRAC channel activation. FASEB J. 2007 doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9449com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Darbellay B, et al. Human muscle economy myoblast differentiation and excitation-contraction coupling use the same molecular partners: STIM1 and STIM2. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(29):22437–22447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hoth M, Penner R. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature. 1992;355(6358):353–356. doi: 10.1038/355353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Feske S, et al. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441(7090):179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vig M, et al. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006;312(5777):1220–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lewis RS. Store-operated calcium channels. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1999;33:279–307. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(99)80014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rios E, Pizarro G, Stefani E. Charge movement and the nature of signal transduction in skeletal muscle excitation-contraction coupling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1992;54:109–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.54.030192.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].MacLennan DH. Ca2+ signalling and muscle disease. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267(17):5291–5297. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Periasamy M, Kalyanasundaram A. SERCA pump isoforms: their role in calcium transport and disease. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35(4):430–442. doi: 10.1002/mus.20745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sacchetto R, et al. Colocalization of the dihydropyridine receptor: the plasma-membrane calcium ATPase isoform 1 and the sodium/calcium exchanger to the junctional-membrane domain of transverse tubules of rabbit skeletal muscle. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;237(2):483–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0483k.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Levitsky DO. Three types of muscles express three sodium–calcium exchanger isoforms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1099:221–225. doi: 10.1196/annals.1387.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nicoll DA, et al. Cloning of a third mammalian Na+–Ca2+ exchanger: NCX3. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271(40):24914–24921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kurebayashi N, Ogawa Y. Depletion of Ca2+ in the sarcoplasmic reticulum stimulates Ca2+ entry into mouse skeletal muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 2001;533(Pt 1):185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0185b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ma J, Pan Z. Junctional membrane structure and store operated calcium entry in muscle cells. Front. Biosci. 2003;8:D242–D255. doi: 10.2741/977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Pan Z, et al. Dysfunction of store-operated calcium channel in muscle cells lacking mg29. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4(5):379–383. doi: 10.1038/ncb788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Launikonis BS, Barnes M, Stephenson DG. Identification of the coupling between skeletal muscle store-operated Ca2+ entry and the inositol trisphosphate receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100(5):2941–2944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536227100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Allard B, et al. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and depletion fail to affect sarcolemmal ion channel activity in mouse skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2006;575(Pt 1):69–81. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Launikonis BS, Rios E. Store-operated Ca2+ entry during intracellular Ca2+ release in mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2007;583(Pt 1):81–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hawkins BJ, et al. S-glutathionylation activates STIM1 and alters mitochondrial homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190(3):391–405. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Pozo-Guisado E, et al. Phosphorylation of STIM1 at ERK1/2 target sites modulates store-operated calcium entry. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 18):3084–3093. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Manji SS, et al. STIM1: a novel phosphoprotein located at the cell surface. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1481(1):147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Smyth JT, et al. Phosphorylation of STIM1 underlies suppression of store-operated calcium entry during mitosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11(12):1465–1472. doi: 10.1038/ncb1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Yu F, Sun L, Machaca K. Orai1 internalization and STIM1 clustering inhibition modulate SOCE inactivation during meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S. A. 2009;106(41):17401–17406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904651106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Liou J, et al. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 2005;15(13):1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Roos J, et al. STIM1: an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169(3):435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Stathopulos PB, et al. Stored Ca2+ depletion-induced oligomerization of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) via the EF-SAM region: An initiation mechanism for capacitive Ca2+ entry. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(47):35855–35862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Williams RT, et al. Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1): a transmembrane protein with growth suppressor activity, contains an extracellular SAM domain modified by N-linked glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1596(1):131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(02)00211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Huang GN, et al. STIM1 carboxyl-terminus activates native SOC: I(crac) and TRPC1 channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8(9):1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/ncb1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Mercer JC, et al. Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor: Stim1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(34):24979–24990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604589200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Soboloff J, et al. Orai1 and STIM reconstitute store-operated calcium channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(30):20661–20665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Peinelt C, et al. Amplification of CRAC current by STIM1 and CRACM1 (Orai1) Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8(7):771–773. doi: 10.1038/ncb1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Prakriya M, et al. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443(7108):230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Liou J, et al. Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(22):9301–9306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702866104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Parekh AB. Store-operated CRAC channels: function in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9(5):399–410. doi: 10.1038/nrd3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wu MM, et al. Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174(6):803–813. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hauser CT, Tsien RY. A hexahistidine-Zn2+-dye label reveals STIM1 surface exposure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(10):3693–3697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611713104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. STIM1 regulates Ca2+ entry via arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels without store depletion or translocation to the plasma membrane. J. Physiol. 2007;579(Pt 3):703–715. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.122432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Wissenbach U, et al. Primary structure, chromosomal localization and expression in immune cells of the murine ORAI and STIM genes. Cell Calcium. 2007;42(4-5):439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Yeromin AV, et al. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 2006;443(7108):226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature05108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Vig M, et al. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr. Biol. 2006;16(20):2073–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Liao Y, et al. Orai proteins interact with TRPC channels and confer responsiveness to store depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(11):4682–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611692104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Lopez JJ, et al. Interaction of STIM1 with endogenously expressed human canonical TRP1 upon depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(38):28254–28264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Yuan JP, et al. STIM1 heteromultimerizes TRPC channels to determine their function as store-operated channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):636–645. doi: 10.1038/ncb1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Shuttleworth TJ, Thompson JL, Mignen O. STIM1 and the noncapacitative ARC channels. Cell Calcium. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. The molecular architecture of the arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective ARC channel is a pentameric assembly of Orai1 and Orai3 subunits. J. Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 17):4181–4197. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].McCarl CA, et al. ORAI1 deficiency and lack of store-operated Ca2+ entry cause immunodeficiency, myopathy, and ectodermal dysplasia. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;124(6):1311–1318. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Pette D, Staron RS. Transitions of muscle fiber phenotypic profiles. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2001;115(5):359–372. doi: 10.1007/s004180100268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Pette D, Staron RS. Molecular basis of the phenotypic characteristics of mammalian muscle fibres. Ciba Found. Symp. 1988;138:22–34. doi: 10.1002/9780470513675.ch3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Williams RS, Rosenberg P. Calcium-dependent gene regulation in myocyte hypertrophy and remodeling. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2002;67:339–344. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2002.67.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Dolmetsch RE, et al. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 1997;386(6627):855–858. doi: 10.1038/386855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Wu H, et al. MEF2 responds to multiple calcium-regulated signals in the control of skeletal muscle fiber type. EMBO J. 2000;19(9):1963–1973. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Naya FJ, et al. Stimulation of slow skeletal muscle fiber gene expression by calcineurin in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(7):4545–4548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Oh M, et al. Calcineurin is necessary for the maintenance but not embryonic development of slow muscle fibers. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25(15):6629–6638. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6629-6638.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Feske S, et al. A severe defect in CRAC Ca2+ channel activation and altered K+ channel gating in T cells from immunodeficient patients. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202(5):651–662. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Le Deist F, et al. A primary T-cell immunodeficiency associated with defective transmembrane calcium influx. Blood. 1995;85(4):1053–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Partiseti M, et al. The calcium current activated by T cell receptor and store depletion in human lymphocytes is absent in a primary immunodeficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269(51):32327–32335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Picard C, et al. STIM1 mutation associated with a syndrome of immunodeficiency and autoimmunity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360(19):1971–1980. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Whitehead NP, et al. Streptomycin reduces stretch-induced membrane permeability in muscles from mdx mice. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2006;16(12):845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Suchyna TM, Sachs F. Mechanosensitive channel properties and membrane mechanics in mouse dystrophic myotubes. J. Physiol. 2007;581(Pt 1):369–387. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Hayakawa K, Tatsumi H, Sokabe M. Actin stress fibers transmit and focus force to activate mechanosensitive channels. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 4):496–503. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Coste B, et al. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science. 2010;330(6000):55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1193270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Maroto R, et al. TRPC1 forms the stretch-activated cation channel in vertebrate cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7(2):179–185. doi: 10.1038/ncb1218. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Gottlieb P, et al. Revisiting TRPC1 and TRPC6 mechanosensitivity. PflugersArch. 2008;455(6):1097–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Mederos y Schnitzler M, et al. Gq-coupled receptors as mechanosensors mediating myogenic vasoconstriction. EMBO J. 2008;27(23):3092–3103. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Vandebrouck A, et al. Regulation of capacitative calcium entries by alpha1-syntrophin: association of TRPC1 with dystrophin complex and the PDZ domain of alpha1-syntrophin. FASEB J. 2007;21(2):608–617. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6683com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Stiber JA, et al. Mice lacking Homer 1 exhibit a skeletal myopathy characterized by abnormal transient receptor potential channel activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28(8):2637–2647. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01601-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Ducret T, et al. Functional role of store-operated and stretch-activated channels in murine adult skeletal muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 2006;575(Pt 3):913–924. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Boittin FX, et al. Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 enhances store-operated Ca2+ entry in dystrophic skeletal muscle fibers. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 18):3733–3742. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Betzenhauser MJ, Marks AR. Ryanodine receptor channelopathies. PflugersArchiv. 2010;460(2):467–480. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0794-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Duke AM, et al. Store-operated Ca2+ entry in malignant hyperthermia-susceptible human skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(33):25645–25653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]