Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine how trajectories of smoking observed over a 34-year period, were associated with the progression of mobility impairment, musculoskeletal pain, and symptoms of psychological distress from midlife to old age.

METHOD

The Swedish Level of Living Survey (LNU) and the Swedish Panel Study of the Oldest Old (SWEOLD) were merged to create a nationally representative longitudinal sample of Swedish adults (aged 30–50 at baseline; n=1,060), with four observation periods, from 1968 through 2002. Five discrete smoking trajectory groups were treated as predictors of variation in health trajectories using multilevel regression.

RESULTS

At baseline, there were no differences in mobility impairment between smoking trajectory groups. Over time all smokers, particularly persistent and former heavy smokers, exhibited faster increases in mobility problems compared to persistent non-smokers. Additionally, all smoking groups reported more pain symptoms than the non-smokers, at baseline and over time, but most of these differences did not reach statistical significance. Persistent heavy smokers reported elevated levels of psychological distress at baseline and over time.

CONCLUSION

Smokers, and even some former smokers, who survive into old age appear to be at increased risk for non-life-threatening conditions that can diminish quality of life and increase demands for services.

Keywords: smoking, aging, middle aged, health

INTRODUCTION

Numerous studies have reported, and repeatedly confirm, the strong associations between tobacco smoking and several life-threatening diseases, such as cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases, as well as various cancers (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004). These associations are responsible for smoking being consistently ranked among the top modifiable risk factors for mortality in modern society (McGinnis and Foege, 1993; Mokdad et al., 2004). Still, while most types of exposure to smoking increase risk for life-threatening diseases and mortality, the life expectancies of people with different histories of smoking (e.g., light vs. heavy smokers; short-term vs. long-term smokers) have been found to be quite disparate (Doll et al., 2004; Frosch et al., 2009; Gerber et al., 2012). As a result of this variation, as well as the increasing life expectancy in the population in general, a growing number of adults with a history of smoking behavior are reaching old age, and may be subject to risk for a number of substantial and debilitating health problems (Rosen and Haglund, 2005).

One category of potential health consequences of smoking that has received relatively little attention is that of non-life-threatening diseases and conditions among smokers who survive into old age. In a Finnish study with 26 years of follow-up, a graded association was found between the daily number of cigarettes at baseline and health-related quality of life among survivors into old age. The largest differences were found between heavy smokers and never-smokers in the physical dimension of health-related quality of life (Strandberg et al., 2008). In the Nurses’ Health Study, current smokers scored lower on both the physical and mental components of health-related quality of life compared to both the never-smokers and former smokers (ages 29 to 71 years). However, 8-year changes in the physical and mental components of health-related quality of life were similar for persistent smokers and those who quit smoking during the follow-up (Sarna et al., 2008), perhaps suggesting that the amount of smoking or a longer follow-up time must be considered.

To our knowledge, patterns of smoking behavior, measured prospectively from midlife to old age, have not been investigated in relation to the progression of non-life-threatening, age-related, health conditions during this same period. In the present study we investigated the progression of mobility impairment, musculoskeletal pain and symptoms of psychological distress—three common non-lifethreatening conditions that are also important dimensions of health-related quality of life—and their associations with different patterns of smoking over a 34-year period. Studying the linkages between smoking trajectories and health trajectories as people enter old age allows us to examine how the amount and persistence of smoking may influence one’s health prospects during the aging process.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study sample

This study used data from the Swedish Level of Living Survey (LNU) and the Swedish Panel Study of Living Conditions of the Oldest Old (SWEOLD). LNU is a longitudinal, nationally representative, study of the Swedish adult population, ages 18–75. It was first carried out in 1968, and subsequently in 1974, 1981, 1991, 2000 and 2010 (Fritzell and Lundberg, 2007). Persons from the LNU sample who have passed the upper age limit of 75 years were included in the SWEOLD study (Lundberg and Thorslund, 1996). SWEOLD has been carried out in 1992, 2002, 2004 and 2011. In both studies, professional interviewers conducted structured interviews with participants in their homes. The interviews addressed questions about work life, family situation, health behaviors, economic conditions, living conditions and health status.

In the current study, data from LNU 1968, 1981, 1991 and 2000 were merged with data from SWEOLD 2002. Together, these datasets allow for up to 34 years of follow-up among a subsample of individuals ages 30–50 at baseline (1968). Only individuals who were interviewed in 1968 and in at least two of the subsequent waves of data collection were included in the study. Of the 2051 individuals aged 30–50 in 1968, 655 persons (32%) died during follow-up and 336 persons (16%) did not participate in two or more of the following data collections or had missing values in the included variables. The final analytic sample consisted of 1,060 persons (52% of the original sample, 76% of the survivors).

Measurements

Each individual’s smoking pattern over time, or trajectory, was identified based on smoking status in 1968, 1981, 1991 and 2000/2002. Smoking status at each wave was classified as either current nonsmoking, light smoking (i.e., smoking less than 10 cigarettes/day), or heavy smoking (i.e., smoking 10 or more cigarettes/day). Distinctive, homogenous, trajectory groups were created manually according to a set of rules. Persistent heavy smokers (n=81) were defined as those who reported smoking throughout the period, with heavy smoking reported during at least three time-points. Similarly, persistent light smokers (n=63) were those who reported smoking throughout the followup period, but with two or fewer episodes of heavy smoking. The trajectory groups of former smokers consisted of those reporting smoking in the first and/or second waves of data collection, but no smoking in the final wave. Former heavy smokers (n=107) reported mostly heavy smoking, while former light smokers (n=176) primarily reported light smoking. Finally, the persistent non-smokers were those who never reported any smoking (n=633, reference category).

Three non-life-threatening health outcomes covering different aspects of late-life health and function were investigated. Mobility impairment was measured with a summary index of three items: the ability to walk 100 meters without difficulties, to run 100 meters without difficulties, and to go upstairs and downstairs without difficulties. Responses were yes (0) and no (1). The summed index ranged from no mobility problems (0) to problems in all three domains (3). The indices of Musculoskeletal pain and Symptoms of psychological distress were both based on items from a list of common diseases and symptoms. Respondents were asked whether they had any of the listed diseases or health problems during the last twelve months. Responses were no (0); yes, slight problems (1); and yes, severe problems (2). The index of Musculoskeletal pain consisted of three questions regarding perceived pain in hands, elbows, legs or knees; shoulders; and back, hips, sciatica. Responses to these three questions were summed, creating a summary score ranging from 0 (no musculoskeletal pain) to 6 points (severe pain in all three sites). Similarly, the index of Symptoms of psychological distress consisted of four questions regarding anxiety, nervousness, anguish; general fatigue; sleeping problems; and depression. Depression rendered 2 points independent of severity. The total score ranged from 0 (no symptoms of psychological distress) to 8 points (severe problems in all measured domains of psychological distress). These measures have been used in previous studies, as indices as well as dichotomous variables (Fors et al., 2008; Meinow et al., 2006; Schön and Parker, 2009).

Age was measured continuously in years (at baseline). Educational level was measured continuously as completed years of education.

Statistical analyses

Bi- and multivariate multinomial regression analyses were run to compare the smoking groups with the persistent non-smokers across various demographic and health characteristics (using SPSS Statistics 20). Furthermore, this study employed multilevel models, with occasions of measurement nested within individuals (Hox, 2002; Shaw and Liang, 2011), in order to model individual-level changes in health over time (measured as years since baseline). Mobility problems, musculoskeletal pain and symptoms of psychological distress were used as time-varying outcome variables. The smoking trajectory groups, age, gender and education were entered as time-fixed predictors of interindividual variation in the health trajectories. Non-linear changes in health over time were estimated by using the quadratic function, but in order to simplify the models, random effects were not estimated for the quadratic term. This allowed us to describe accurately the average pattern of nonlinear change in each health outcome, while focusing only on examining inter-individual variation in the intercepts and linear slopes of the health trajectories. Analyses were run using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) software (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002).

RESULTS

Approximately 40% of the sample reported some level of smoking during the study period. Descriptive statistics for the persistent non-smokers and the four trajectory groups of smokers are presented in Table 1. All smoking groups, except for the persistent light smokers, had a higher proportion of men compared to the persistent non-smokers. Furthermore, heavy smokers were significantly younger and more highly educated compared to the persistent non-smokers. Baseline health differences were found for musculoskeletal pain, where the former light smokers reported significantly more pain symptoms, and for psychological distress, where the persistent heavy smokers had significantly higher symptom scores than the non-smokers. However, none of the smoking groups differed significantly from the non-smokers in mobility impairment. Adjusting for the included covariates did not change these results (see also Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptives for the five smoking trajectory groups in 1,060 persons aged 30–50 at baseline (1968), Level of Living Survey, Sweden 1968.a

| Persistent non-smokers (n=633) |

Former light smokers (n=176) |

Former heavy smokers (n=107) |

Persistent light smokers (n=63) |

Persistent heavy smokers (n=81) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |||||

| Men | 37.8 | 52.8*** | 79.4*** | 36.5 | 53.1** |

| Women | 62.2 | 47.2 | 20.6 | 63.5 | 46.9 |

| Age | |||||

| Mean age (SD) | 39.6 (6.0) | 38.9 (5.8) | 38.5 (6.1) | 39.2 (5.8) | 35.8*** (5.0) |

| Range (age) | 30–50 | 30–50 | 30–50 | 30–50 | 30–49 |

| Education | |||||

| Mean education | 8.5 (3.1) | 8.7 (3.0) | 9.0 (3.4) | 8.1 (2.6) | 9.2* (2.9) |

| years (SD) | |||||

| Range (edu yrs) | 0–24 | 5–20 | 6–20 | 5–16 | 4–20 |

| Health at baseline (1968) |

|||||

| Mobility | 0.18 (0.56) | 0.19 (0.63) | 0.15 (0.58) | 0.27 (0.75) | 0.14 (0.52) |

| impairment (mean value, SD and range) |

(0–3) | (0–3) | (0–3) | (0–3) | (0–3) |

| Musculoskeletal | 0.68 (1.07) | 0.89* (1.33) | 0.68 (0.97) | 0.97 (1.27) | 0.81 (1.42) |

| pain (mean value, SD and range) |

(0–6) | (0–6) | (0–4) | (0–6) | (0–5) |

| Psychological | 0.59 (1.26) | 0.66 (1.43) | 0.46 (1.00) | 0.79 (1.48) | 0.93* (1.51) |

| distress (mean value, SD and range) |

(0–8) | (0–8) | (0–5) | (0–6) | (0–6) |

p<=.05,

p<=.01,

p<=.001

Significant differences refer to comparisons with the group of persistent non-smokers

Table 2.

Coefficients (and standard errors) from multilevel models for the association between smoking trajectories and trajectories of mobility impairment, musculoskeletal pain and symptoms of psychological distress over 34 years of follow-up in 1,060 persons aged 30–50 at baseline, Level of Living Survey and SWEOLD study, Sweden 1968–2002.

| Mobility impairment |

Musculoskeletal pain | Psychological distress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.19*** | (0.021) | 0.66*** | (0.042) | 0.55*** | (0.046) |

| Non-smokers | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | |||

| Former light smokers | 0.01 | (0.052) | 0.25* | (0.111) | 0.19 | (0.110) |

| Former heavy smokers | −0.002 | (0.061) | 0.14 | (0.113) | 0.08 | (0.104) |

| Persistent light smokers | 0.03 | (0.095) | 0.20 | (0.165) | 0.15 | (0.179) |

| Persistent heavy smokers | −0.009 | (0.069) | 0.24 | (0.163) | 0.50*** | (0.166) |

| Age | 0.004 | (0.003) | 0.007 | (0.006) | −0.005 | (0.006) |

| Gender (woman) | 0.15*** | (0.036) | 0.26*** | (0.072) | 0.49*** | (0.072) |

| Years of education | −0.01* | (0.005) | −0.07*** | (0.010) | −0.02* | (0.006) |

| Linear slope | −0.007** | (0.003) | 0.05*** | (0.005) | −0.01*** | (0.004) |

| Non-smokers | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | |||

| Former light smokers | 0.006* | (0.003) | −0.001 | (0.004) | −0.0009 | (0.004) |

| Former heavy smokers | 0.01** | (0.003) | 0.005 | (0.005) | 0.002 | (0.005) |

| Persistent light smokers | 0.007 | (0.005) | 0.003 | (0.007) | −0.0004 | (0.006) |

| Persistent heavy smokers | 0.01*** | (0.004) | 0.0007 | (0.005) | −0.004 | (0.006) |

| Age | 0.001*** | (0.0001) | −0.0003 | (0.0003) | 0.0007** | (0.0003) |

| Gender (woman) | 0.005** | (0.002) | 0.009** | (0.003) | 0.003 | (0.002) |

| Years of education | −0.001*** | (0.0003) | −0.0003 | (0.0004) | −0.0004 | (0.0004) |

| Quadratic slope | 0.0009*** | (0.0001) | −0.0007*** | (0.0001) | 0.0009*** | (0.0001) |

| Random effects | ||||||

| Variances | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.08*** | 0.45*** | 0.58*** | |||

| Linear slope | 0.0004*** | 0.0005*** | 0.0007*** | |||

p<=.05,

p<=.01,

p<=.001

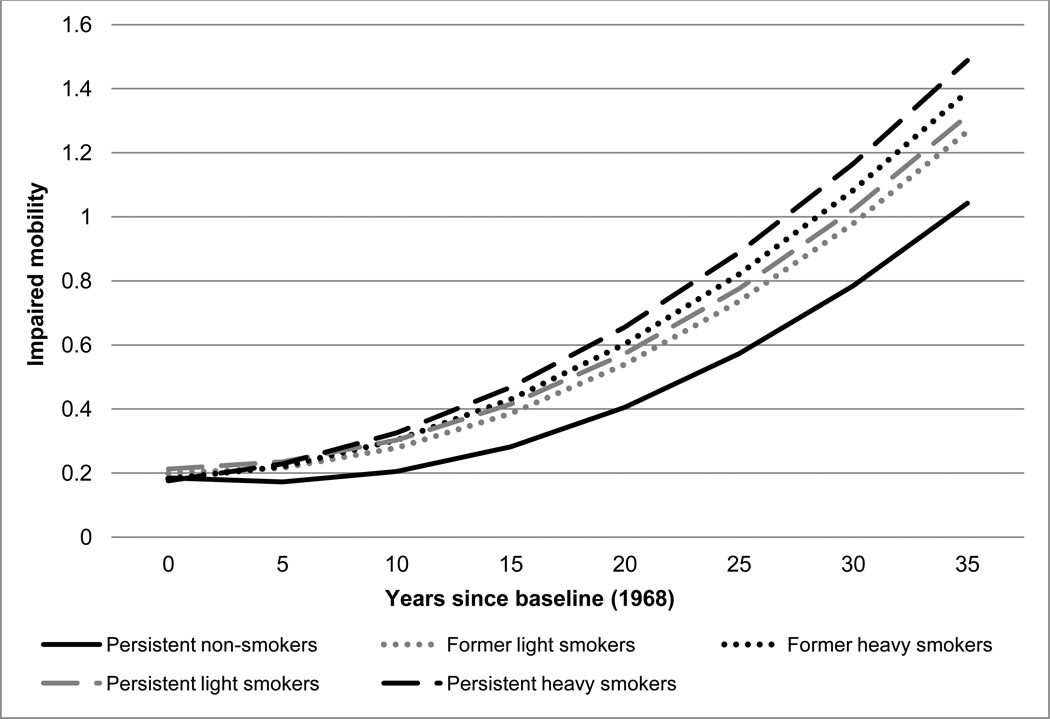

Results from the multilevel models are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1–Figure 3. Figure 1 shows the association between smoking trajectory groups and the progression of mobility impairment from midlife to old age, controlling for age, gender and education. As presented in the first column of coefficients from Table 2, at baseline, there were no significant differences in mobility problems between the smoking trajectory groups; however the rates of increase in mobility problems over time did differ. Mobility problems increased at an accelerating rate in the persistent non-smoking group over the 34-year period of follow-up, but each of the other smoking trajectory groups exhibited faster increases in mobility impairment. The rate of increase in mobility impairment was steepest among persistent heavy smokers, followed by former heavy smokers. Persistent and former light smokers had steeper progression of mobility problems too, but only the slope for the former light smokers was statistically different from that of the persistent non-smokers.

Figure 1.

Associations between smoking trajectories and trajectories of mobility impairment over 34 years of follow-up in 1,060 persons aged 30–50 at baseline, Level of Living Survey and SWEOLD study, Sweden 1968–2002.

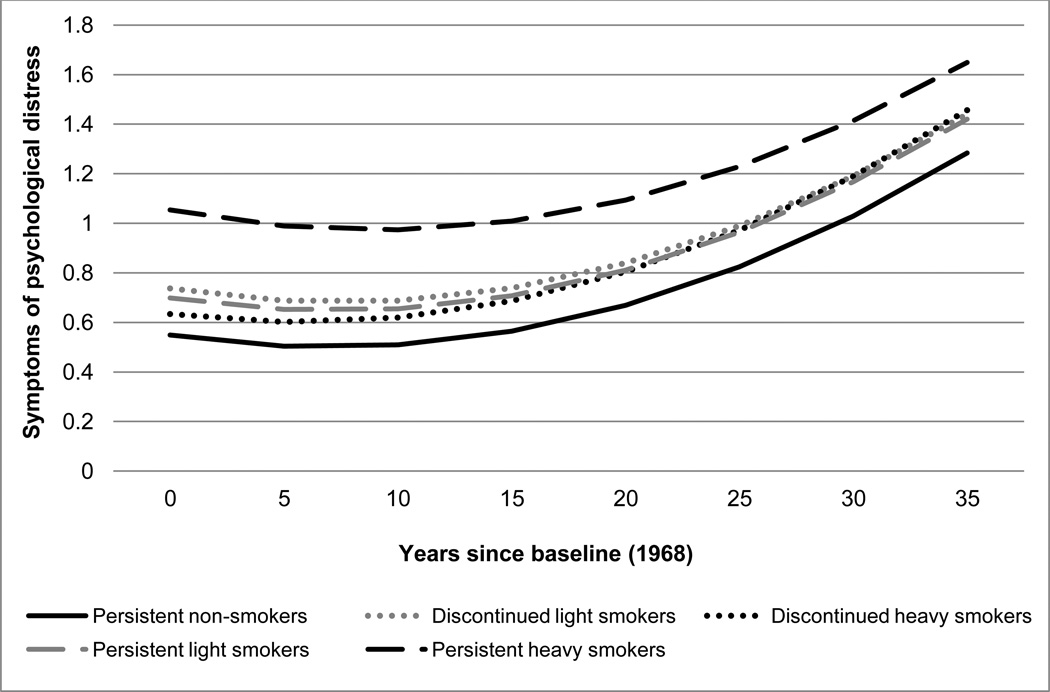

Figure 3.

Associations between smoking trajectories and trajectories of symptoms of psychological distress over 34 years of follow-up in 1,060 persons aged 30–50 at baseline, Level of Living Survey and SWEOLD study, Sweden 1968–2002.

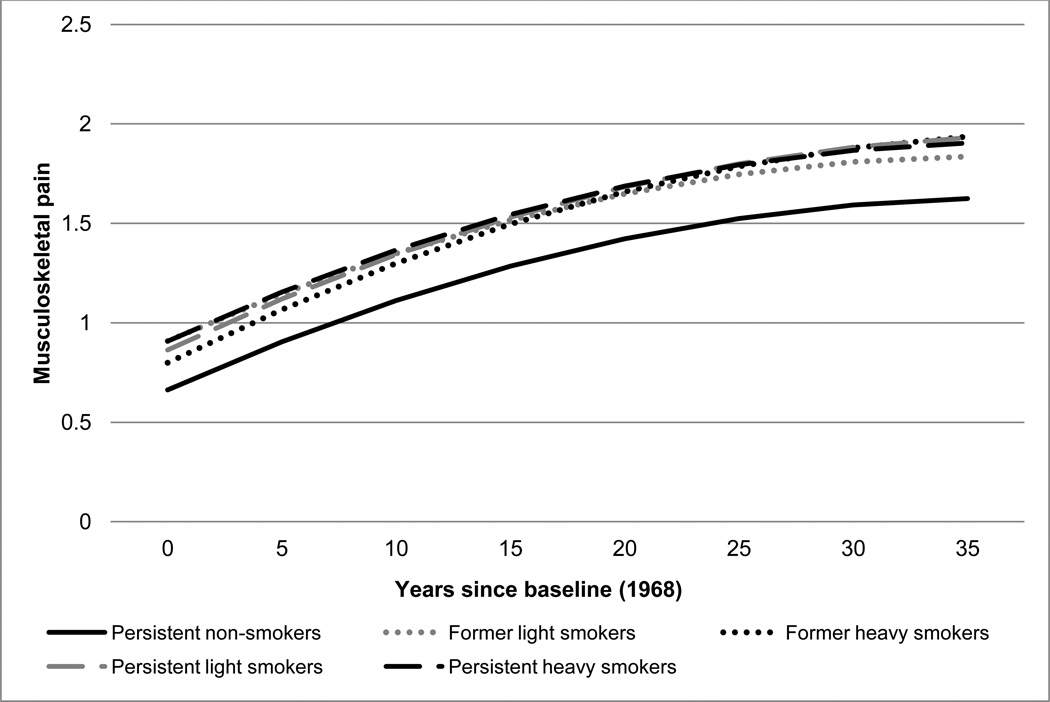

Similarly, column two of Table 2, and Figure 2, show results for the association between smoking trajectories and trajectories of musculoskeletal pain. Compared to persistent non-smokers, all smoking groups reported more pain symptoms at baseline, but the only baseline difference that was statistically significant was that for former light smokers. Over time, musculoskeletal pain increased at a decelerating rate among persistent non-smokers, and there were no differences between the smoking trajectory groups in the rate of increase. As such, baseline differences in musculoskeletal pain between the groups persisted over time.

Figure 2.

Associations between smoking trajectories and trajectories of musculoskeletal pain over 34 years of follow-up in 1,060 persons aged 30–50 at baseline, Level of Living Survey and SWEOLD study, Sweden 1968–2002.

In column three of Table 2, and Figure 3, the association between smoking trajectories and symptoms of psychological distress is shown. Compared to persistent non-smokers, persistent heavy smokers had higher levels of psychological distress at baseline and this difference did not change over time. Psychological distress increased at an accelerating rate over time in the persistent nonsmoking group, and this rate of increase was similar in all of the smoking trajectory groups.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to investigate the association between trajectories of smoking, including the amount and persistence of smoking, and the development of non-life-threatening health problems over a 34-year period, from midlife to old age. Results varied by health outcome; whereas no baseline differences in mobility impairment between the smoking trajectory groups were evident, the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and symptoms of psychological distress did differ at baseline. Conversely, no differences in the progression of musculoskeletal pain and psychological distress between the different smoking trajectory groups were evident, whereas the progression of mobility impairment over time was steeper among smokers compared to persistent non-smokers. More specifically, our findings suggest that a history of smoking, especially heavy smoking, with or without quitting, is associated with an earlier onset, and a faster elevation, of mobility problems during the transition from middle age to old age. This suggests that many smokers, and even former smokers, who survive to old age, may be at an increased risk for becoming disabled and dependent during this stage of life. A possible explanation for the earlier onset and faster elevation of mobility problems among those with histories of smoking may be the higher prevalences of lung problems, cardiovascular diseases and stroke that are associated with smoking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004).

Still, consistent with research on the health and survival benefits associated with quitting smoking (Doll et al., 2004; Frosch et al., 2009; Ostbye et al., 2002), we expected the health trajectories of persons who quit smoking during follow-up to become more similar to the persistent non-smokers over time. Remarkably, the trajectories of the quitters were more similar to those of the persistent smokers than the persistent non-smokers, particularly for mobility impairment and musculoskeletal pain. In the case of mobility impairment, both former and persistent smokers exhibited faster increases in mobility problems than non-smokers, while in the case for musculoskeletal pain, former and persistent smokers exhibited higher levels of pain at baseline (significant only for former light smokers) that were maintained throughout the follow-up. Similarities in changes over time for former and persistent smokers were also reported in a study investigating the association with health-related quality of life (Sarna et al., 2008). This may be due to the damage caused by the many years of smoking, which at this stage may not be easily repaired or compensated even with smoking cessation.

Elevated risk for health problems associated with former smokers may also be due to the fact that smoking cessation in many cases is prompted by health problems. If this is the case, individuals in better health will be in the persistent smoking groups, decreasing the health differences between these groups. The mutual influence these factors exert on each other, however, cannot be separated in this study since the trajectories are concurrent.

With regard to musculoskeletal pain and psychological distress, baseline differences across smoking groups appear to persist with advancing age. Thus, the particular magnitude of these baseline differences may be especially informative. When considering pain (Figure 2), our findings show a trend towards persistent non-smokers differing from each of the groups of smokers, irrespective of the amount and persistence of smoking. Previous research on pain and smoking has indicated that smokers are more likely to report pain, and persons with chronic pain are more likely to smoke. Some have suggested that smoking and pain in fact reinforce each other (Ditre et al., 2011). The clustering of smokers’ pain trajectories in the current study is consistent with these findings, but also indicates that this reciprocity is diminished as individuals transition from middle age to old age. As mentioned above, individuals who quit smoking showed no reductions of pain over time.

When considering psychological distress, it appears as if the persistent heavy smokers stand out in comparison to the other groups of lighter smokers and non-smokers. The association between smoking and psychological distress resembles the association between smoking and pain, in that they appear to reinforce each other (Ditre et al., 2011), in part because similar neurotransmitter pathways are involved in both smoking and depression (Quattrocki et al., 2000). Smokers more commonly have recurring depression, but it is also more common for persons with depression to start smoking again after smoking cessation (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004). However, in this study only the persistent heavy smokers reported a higher prevalence of psychological distress throughout the 34-year follow-up period, whereas all other types of smoking behavior clustered together with the persistent non-smokers (Figure 3).

Study limitations and strengths

Several aspects of this study make it unique: it utilized a population-based sample, with a high response-rate and a long follow-up time of 34 years with repeated measures from midlife into old age. Smoking status as well as the three health indicators were measured prospectively at four timepoints. Also, being able to differentiate between light and heavy smoking is a clear advantage, although the level of smoking was crudely measured.

At the same time, selective survival is important to consider when investigating the aging process, particularly when studying risky behaviors. Smokers have a particularly high mortality risk, and so a large proportion of the persistent smokers, especially the heavy smokers, have died before reaching old age. This leaves primarily the healthier individuals in the sample, as indicated by the descriptive characteristics in Table 1: persistent heavy smokers were younger, had higher education, less mobility problems and a large proportion of women (especially considering the low proportion of women smokers in 1968, when this study was initiated). Nonetheless as this study aims to assess the health prospects of survivors into old age, and non-response is low, selective survival is not considered to be a major concern. Most likely, our estimated associations between smoking and nonlife-threatening conditions have been attenuated, as many smokers and persons with impaired health have died and are not included in this study. Indeed, supplemental analyses (not shown here) indicated that persons who died during follow-up were older, less well educated, more likely to smoke, and had more mobility impairment and psychological distress at baseline compared to those who were included in the study.

Additionally, our estimated associations between smoking and health may be attenuated due to the fact that the younger segments of our sample were followed only through 2000 (the final wave of LNU), while the older segments were followed through 2002 (SWEOLD). As such, the period for observing the development of health problems was slightly shorter for the younger segments of our sample than it was for the older respondents. Because the persistent heavy smoking group contained a high number of younger individuals, the level of health problems that we observed in this group throughout the study period was probably underestimated. For similar reasons, our estimates of the association between age and the health trajectories may be slightly overestimated.

In conclusion, our study suggests that smokers, and in some cases former smokers, who survive into old age are at increased risk for non-life-threatening conditions that can diminish quality of life and increase the demand for services. If increases in longevity within certain segments of the population occur without corresponding delays in the onset of disease and disability, the result could be an expanded period of morbidity during later life as well as a dramatic rise in associated health care costs (Manton and Gu, 2001).

Highlights.

Trajectories of smoking and non-life-threatening conditions were studied

Persistent and former heavy smokers had the steepest increases in mobility problems

All smokers reported more pain symptoms than non-smokers, at baseline and over time

Heavy smokers reported elevated levels of psychological distress, at baseline and over time

Many older smokers and former smokers are at risk for non-life-threatening conditions

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ditre JW, Brandon TH, Zale EL, Meagher MM. Pain, nicotine, and smoking: research findings and mechanistic considerations. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:1065–1093. doi: 10.1037/a0025544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fors S, Lennartsson C, Lundberg O. Health inequalities among older adults in Sweden 1991–2002. European Journal of Public Health. 2008;18:138–143. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzell J, Lundberg O. Health Inequalities and Welfare Resources. Policy Press, Bristol. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Frosch ZA, Dierker LC, Rose JS, Waldinger RJ. Smoking trajectories, health, and mortality across the adult lifespan. Addict Behav. 2009;34:701–704. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber Y, Myers V, Goldbourt U. Smoking reduction at midlife and lifetime mortality risk in men: a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:1006–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg O, Thorslund M. Fieldwork and measurement considerations in surveys of the oldest old. Experiences from the Swedish level of living surveys. Social Indicators Research. 1996;37:165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Manton KG, Gu X. Changes in the prevalence of chronic disability in the United States black and nonblack population above age 65 from 1982 to 1999. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6354–6359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111152298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:2207–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinow B, Parker MG, Kåreholt I, Thorslund M. Complex health problems in the oldest old in Sweden 1992–2002. European Journal of Ageing. 2006;3:198–106. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0027-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostbye T, Taylor DH, Jung SH. A longitudinal study of the effects of tobacco smoking and other modifiable risk factors on ill health in middle-aged and old Americans: results from the Health and Retirement Study and Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old survey. Prev Med. 2002;34:334–345. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocki E, Baird A, Yurgelun-Todd D. Biological aspects of the link between smoking and depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2000;8:99–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierachical linear models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen M, Haglund B. From healthy survivors to sick survivors--implications for the twenty-first century. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33:151–155. doi: 10.1080/14034940510032121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna L, Bialous SA, Cooley ME, Jun HJ, Feskanich D. Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on health-related quality of life in women in the Nurses' Health Study. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:1217–1227. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9404-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schön P, Parker MG. Sex Differences in Health in 1992 and 2002 Among Very Old Swedes. Population Ageing. 2009;1:107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BA, Liang J. Growth Models with Multilevel Regression. In: Newsom JT, Jones RN, Hofer SM, editors. Longitudinal Data Analysis. A Practical Guide for Researchers in Aging, Health, and Social Sciences. London: Routledge Academic; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Strandberg AY, Strandberg TE, Pitkala K, Salomaa VV, Tilvis RS, Miettinen TA. The effect of smoking in midlife on health-related quality of life in old age: a 26-year prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1968–1974. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.18.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]