Abstract

Retention in care is key to effective HIV treatment, but half of PLWHA in the U.S. are continuously engaged in care. Incarcerated individuals are an especially challenging population to retain, and empiric data specific to jail detainees is lacking. We prospectively evaluated correlates of retention in care for 867 HIV-infected jail detainees enrolled in a 10-site demonstration project. Sustained retention in care was defined as having a clinic visit during each quarter in the 6-month post-release period. The following were independently associated with retention: being male (AOR=2.10, p=<0.01), heroin use (AOR 1.49, p=0.04), having an HIV provider (AOR 1.67, p=0.02), and receipt of services: discharge planning (AOR 1.50, p=0.02) and disease management session (AOR 2.25, p=<0.01) during incarceration; needs assessment (AOR 1.59, p=0.02), HIV education (AOR 2.03, p=<0.01), and transportation assistance (AOR 1.54, p=0.02) after release. Provision of education and case management services improve retention in HIV care after release from jail.

Keywords: HIV infection, jail, retention in care, adherence, secondary prevention

Introduction

In 2003, the CDC Advancing HIV Prevention Initiative called for expansion of HIV testing and treatment in the United States (1). While the policy continues to have broad-reaching implications for increased identification of individuals with undiagnosed HIV and linking them to care, the complete continuum of HIV treatment includes retention in HIV care, initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), persistence on and adherence to ART, and achievement of viral suppression, defined as having a non-detectable HIV-1 RNA level (2). In both idealized mathematical models for Sub-Saharan Africa (2) and empiric data from British Columbia (3), higher rates of HIV identification, retention in care, provision of ART, and levels of viral suppression result in significant reductions both in cumulative HIV-associated morbidity and mortality and in transmission rates among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). Advancing this test and treat strategy is consistent with UNAIDS’ goals of “Zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination, zero AIDS-related deaths” by 2015 (4).

Retention in HIV primary care has become the keystone of effective HIV treatment but only half of PLWHA in the US are continuously engaged in care (2, 5). Poor retention in care is associated with increased overall mortality (6). Among correctional populations, in particular, the continuum of HIV care is often disrupted after return to communities by competing priorities for basic subsistence needs, untreated mental illness, relapse to substance use, and lapses in medical or social benefits (7, 8). Previous research confirms that the benefits afforded by ART within prison are rarely sustained after release (9–13). These issues have not yet been fully explored among released jail detainees, but available data suggest that as few as 14% of jail recidivists receive continuous ART (14), a number that is similar to those reported for released HIV-infected prisoners.

Rapid turnover rates in jails, as opposed to prisons, provide a much narrower window in which to diagnose HIV, initiate or continue ART, and link individuals to care using pre-release planning. A systematic investigation of jail detainees’ retention in HIV care after release has vast implications for the health of both individuals and the communities in which they live. We therefore examined predisposing and need factors, as well as enabling resources that are associated with retention in HIV primary care following release from jail.

Methods

Funded by the Health Resources Services Agency, the multisite Enhancing Linkages to HIV Primary Care and Services in Jail Setting Initiative (EnhanceLink) is a Special Project of National Significance that assessed jail-release interventions at ten largely urban US sites, which have previously been described (15). The purpose of the project was to design, implement and evaluate new methods for providing post-release interventions for HIV-infected jail detainees, including linkage to HIV care and other medical services. In most instances, transitional care consisted of case management services, and the majority of sites continued such services post-release. In this analysis, prospective longitudinal data of HIV-infected jail detainees enrolled in the EnhanceLink initiative was evaluated to assess retention in care following release from jail. Baseline and community service referrals and jail and community event records were analyzed to examine the influence of various resources, risk factors, and health behaviors on retention in HIV care.

The Rollins School of Public Health of Emory University and the Abt Associates Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this multisite project. It was also approved and overseen by each individual institutional IRB in accordance with the degree of involvement at each site. In addition, a certificate of confidentiality was obtained.

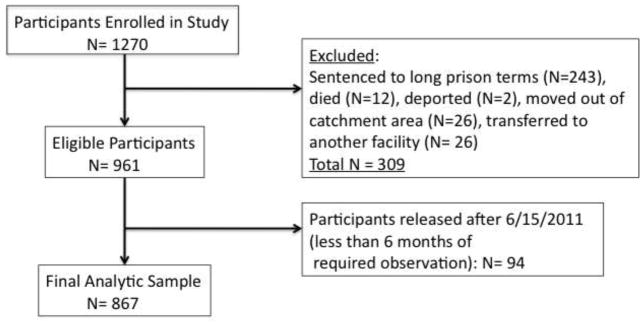

Subject Disposition

Eligibility for participation in the individual-level evaluation was restricted to jail detainees 18 years of age and older. From January 2008 to March 2011, 1270 unique individuals were enrolled and underwent baseline assessment either during incarceration or within 7 days after release. Data were collected by the grantee sites and entered into a web-based data management system. Since retention in care was the primary outcome in our present analysis, we excluded 403 participants who were either sentenced to long prison terms (N=243), died (N=12), were deported (N=2), moved out of the geographic catchment area where data could not be retrieved (N=26), or administratively transferred to non-participating institutions or another correctional facility (N=26). Also excluded were those released after June 15, 2011 (N=94) as they had less than the required 6 months of post-release observation. The final analytic sample consisted of 867 participants (See Figure 1.) Compared to participants in the final analytic sample, the excluded individuals were more likely to be male and less likely to be in a steady relationship at baseline or re-incarcerated by 6 months (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Subject Disposition

Dependent variables

To assess the degree to which participants were engaged in HIV care, viral load (VL) testing was used as a proxy for HIV clinic visits, and data was not dependent on study completion. Three distinct definitions of retention were used: 1) early retention, defined as having an HIV provider visit during days 0–90 after jail release (first quarter) (least stringent); 2) late retention, defined as having an HIV provider visit during days 91–180 after jail release (second quarter); and 3) sustained retention, defined as having two HIV provider visits, one per post-release quarter (most stringent). Viral load data (dates of testing and/or values) was collected by research staff. Upon enrollment and at each study visit, clients indicated their primary HIV clinic, for which chart abstraction was then performed. Intention-to-treat analysis was deployed, meaning that if no VL testing was reported, then it was presumed to be a failure of retention in care for that time period and no imputations were made. While both clinic visit dates and VL test results were collected, the latter was done so more reliably and thus a VL test, which must be ordered by a provider and require a patient’s participation in phlebotomy as per treatment guidelines (16), was used as a proxy for clinic visits.

Independent variables

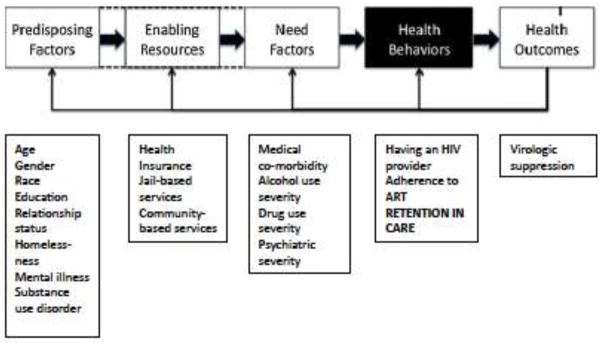

The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (17, 18) was used to define and analyze covariates that may have independently correlated with our primary outcomes of interest. Briefly, this model of healthcare utilization asserts that predisposing factors, enabling resources, and need factors collectively influence health behaviors, such as retention in HIV care, which in turn influence health outcomes. The variables available in our study instruments and utilized here have previously been described and are adapted from our prior work (Figure 2)(7). Additional covariates in this analysis included enabling resources that were provided as part of the jail-release intervention.

Figure 2.

Behavioral Model Adapted from Chen et al. (6) and Gelberg et al. (16)

Predisposing variables were self-reported during baseline interviews and included gender, race and ethnicity, educational level and relationship status. Several measures of mental health were assessed including self-reported depression or anxiety in the 30 days prior to incarceration, presence of bipolar disorder noted in the jail-based medical record, and whether the participant was prescribed psychiatric medication in the 30 days prior to incarceration. Homelessness, another predisposing factor in the theoretical model, was dichotomously defined in accordance with 30-day pre-incarceration housing status as self-reported homeless or sleeping in a shelter, park, empty building, bus station, on the street, or in another public space. An index of incarceration duration was used to measure the length of time subjects spent in jail during their initial stay, and indicators measuring re-incarceration as reported in the one-month post-release follow-up were used to keep track of individuals who returned to jail.

Program-based needs assessments determined which enabling resources were appropriate for participants, and utilization of such services were then included in the analysis: jail-based HIV education, discharge planning, and disease management, as well as community-based HIV education, individual counseling session, arrangement of transportation, and accompaniment to a service provider visit. Case-manager assistance in making various follow-up appointments was also included. These variables were obtained from the community and jail-based event records as reported by project staff and were each recoded dichotomously. Post-release services were community-based, and in some instances were collocated with HIV clinics.

Several need factors were also incorporated. Drug use severity was assessed using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), which was calculated using previously validated cut-offs for alcohol and drug use (19, 20). Recent drug use (within 30 days prior to incarceration) was also evaluated, specifically cocaine, heroin and alcohol consumption. In addition, a psychiatric composite index was compiled for each participant based on answers to survey questions previously described in the ASI Composite Score Manual (21). This scoring has been validated against the 36-item Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36) (22). Because of the chronicity and impact on morbidity and mortality, hepatitis C virus infections were also included as reported in the jail-based medical record.

Previous research has revealed that HIV testing in jails can lead to new diagnoses and identify health needs among the jail population (23, 24). In our analysis we classified participants as newly diagnosed if they affirmed on the baseline survey that their HIV diagnosis was made during their current jail stay. In addition, we used the jail medical records to confirm that participants did not have a prior HIV diagnosis. These methods are consistent with those used in a previous evaluation of the newly diagnosed (23).

Prior health behavior has been associated with future behavior, including adherence to ART. We therefore assessed baseline health behaviors, defined dichotomously, including taking ART within the 7 days prior to incarceration and attainment of 95% self-reported adherence to ART using the Visual Analog Scale during those 7 days. In addition, having a usual HIV provider in the 30 days prior to incarceration was measured per patient report. Virologic suppression (VL<400 copies/mL) at the time of incarceration was also assessed as an independent variable. On average, the baseline VL was recorded approximately 2 weeks into a participant’s jail stay.

Statistical analysis

Approximately 5% of the observations were missing at baseline. To address the issue of the missingness, a series of multiple imputations were performed using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation conditional on the variables that were observed (25). In our analysis, we invoked the Missing at Random (MAR) assumption. Although this assumption cannot be tested directly (26), the MAR assumption is less restrictive than an assumption that specifies non-randomness in the missing data pattern, the violation of which can produce estimates that are more biased than those from an MAR-based analysis (27).

To assess the relationship between the dependent variables and the selected potential covariates, logistic regression was used in three separate models with “lost to care” (no HIV provider visits within the 6-month post-release period) as the referent group. Univariate assessment of each independent variable with the three distinctly defined outcomes (early, late, and sustained retention) was first conducted using the Wald test for both binary and continuous variables. Covariates for each independent measure of retention in care significant at p<0.10 were then included in the final multivariate model. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to discriminate among various multivariate models. As a final check, a Pearson Chi-squared goodness of fit test was used to assess the overall stability of the model. All final models included site location to control for independent fixed effects that were site-specific. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA v.11 (College Station, TX). In addition, sub-analysis was conducted for retention in care among the 36 subjects who were newly diagnosed with HIV during this incarceration.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the 867 eligible participants in this analysis are provided in Table I, which generally reflect HIV infection in criminal justice populations in the US. Most participants were male, Black, not in a steady relationship, in their 40’s, had not completed high school, and were using cocaine in the 30 days before incarceration. They were incarcerated for a mean of 99 days and a median of 56 days. Thirty-seven percent of participants were from one site; the remainder of participants was fairly evenly divided among the other nine sites. Seventy-five percent had some form of health insurance immediately prior to incarceration and 74% reported having a usual HIV provider. Thirty-three percent of those who had ever taken ART reported being at least 95% adherent to medications taken within 7 days of incarceration. During the 6-month post-release follow-up period, 30% of participants were re-incarcerated; these data are reported elsewhere (28).

Table I.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants (N=867)1

| Demographics | N (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 43.0 (8.8) | (42.8, 43.9) |

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 586 (67.6%) | (65.3%, 71.8%) |

| Female | 281 (32.4%) | (28.2%, 34.7%) |

| Race/Ethnicity: | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 137 (15.8%) | (12.4%, 18.1%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 500 (57.7%) | (54.7%, 61.4%) |

| Hispanic | 203 (23.4%) | (20.9%, 29.0%) |

| Other | 27 (3.1%) | (2.4%, 4.1%) |

| Homeless prior to incarceration | 334 (38.5%) | (34.4%, 41.2%) |

| Relationship status: | ||

| In a steady relationship | 283 (32.6%) | (29.2%, 35.8%) |

| Not in a steady relationship | 584 (67.4%) | (64.2%, 70.8%) |

| Education: | ||

| Less than High School | 443 (51.1%) | (46.5%, 53.5%) |

| High School | 290 (33.4%) | (30.8%, 37.5%) |

| Above High school | 134 (15.5%) | (13.2%, 18.3%) |

| Mean duration of index incarceration, days (SD) | 99 (4.3) | (89.6%, 106.5%) |

| Reincarcerated within 6 months | 256 (29.5%) | (27.6%, 34.1%) |

| Health Insurance prior to incarceration | 649 (74.9%) | (73.8%, 79.7%) |

|

| ||

| HIV Care | ||

|

| ||

| Newly diagnosed HIV + | 36 (4.2%) | (2.8%, 5.1%) |

| Taking ART within 7 days of incarceration | 449 (54.1%)2 | (51.6%, 58.8%) |

| ART >/= 95% adherence at baseline | 248 (33.0%)2 | (29.5%, 36.4%) |

| HIV VL<400 at baseline | 267 (30.8%) | (27.3%, 35.5%) |

| Usual HIV care provider at baseline | 641 (73.9%) | (72.0%, 78.1%) |

|

| ||

| Comorbidities | ||

|

| ||

| Depression/anxiety | 488 (56.3%) | (53.0%, 60.0%) |

| Bipolar disorder | 103 (12.0%) | (9.67%, 14.2%) |

| Known Hepatitis C | 327 (37.7%) | (35.3%, 42.1%) |

| Psychiatric medications | 221 (25.5%) | (22.9%, 29.1%) |

| Drug use in 30 days before incarceration: | ||

| Heroin | 232 (26.8%) | (24.3%, 30.5%) |

| Cocaine | 465 (53.7%) | (50.4%, 57.4%) |

| Alcohol | 250 (28.8%) | (24.8%, 31.2%) |

| Severe Drug Use (Above ASI Threshold) | 589 (67.9%) | (64.3%, 70.9%) |

| Severe Alcohol Use (Above ASI Threshold) | 572 (65.9%) | (62.5%, 69.3%) |

| Severe Psychiatric Illness (Above Psychiatric Composite Index) | 463 (53.4%) | (49.8%, 56.8%) |

|

| ||

| Services Received | ||

|

| ||

| During incarceration: | ||

| Jail-based needs assessment | 655 (75.6%) | (72.7%, 78.4%) |

| HIV education | 463 (53.4%) | (50.6%, 57.6%) |

| Discharge planning | 551 (63.5%) | (61.8%, 68.5%) |

| Disease management session | 328 (37.8%) | (35.7%, 42.5%) |

| Community program contact with jail staff | 167 (19.2%) | (16.7%, 22.3%) |

| After release: | ||

| Community-based needs assessment | 519 (59.8%) | (58.8%, 65.6%) |

| HIV education | 290 (33.4%) | (31.1%, 37.7%) |

| One-on-one counseling | 471 (54.3%) | (51.6%, 58.6%) |

| Disease management session | 282 (32.5%) | (30.3%, 36.9%) |

| Arranged/provided transportation | 389 (44.5%) | (41.4%, 48.4%) |

| Accompanied subject to service provider visit | 242 (27.9%) | (25.0%, 31.3%) |

| Appointments scheduled with: | ||

| HIV primary care provider | 531 (61.3%) | (58.8%, 65.6%) |

| Substance abuse counselor | 326 (37.6%) | (35.2%, 42.0%) |

| Mental health counselor | 197 (22.7%) | (19.9%, 25.8%) |

| Housing coordinator | 274 (31.6%) | (27.8%, 35.7%) |

| Other health specialist | 220 (25.3%) | (22.7%, 28.8%) |

| Social service provider | 392 (45.2%) | (42.8%, 49.8%) |

|

| ||

| Sites | ||

|

| ||

| 1 | 62 (7.15%) | (5.4%, 8.9%) |

| 2 | 44 (5.1%) | (3.21%, 6.18%) |

| 3 | 324 (37.4%) | (37.2%, 44.1%) |

| 4 | 58 (6.7%) | (5.20%, 8.77%) |

| 5 | 37 (4.3%) | (3.0%, 5.9%) |

| 6 | 56 (6.5%) | (4.2%, 7.5%) |

| 7 | 77 (8.9%) | (5.9%, 9.6%) |

| 8 | 66 (7.61%) | (5.5%, 9.2%) |

| 9 | 81 (9.3%) | (6.9%, 10.8%) |

| 10 | 62 (7.2%) | (5.2%, 8.8%) |

The absolute numbers for the following variables: relationship status, gender, homelessness, education, mean duration of index of incarceration, health insurance, adherence to ART, HIV viral load, usual HIV provider, heroin, cocaine and alcohol use in the past 30 days, severity of drug use, severity of alcohol use, and severity of psychiatric illness are derived from estimated percentages based on multiple imputations of missing data.

Percent based on number of subjects who have ever taken ART (N=830).

As part of comprehensive jail-based services, 61% (n=531) had an appointment made with a community HIV primary care provider, 38% (n=326) had an appointment made for substance abuse counseling, and 23% (n=197) had an appointment made for mental health counseling. Upon release from jail, 58% of participants (n=500) had an HIV provider visit in the first quarter, and 47% (n= 406) had an HIV provider visit in the second quarter. Among the 36 newly diagnosed subjects in this analysis, 53% (n=19) and 31% (n=11) had visits within the first and second quarters, respectively. Receipt of jail and community-based services (described below) predated HIV provider visits in 57% of cases.

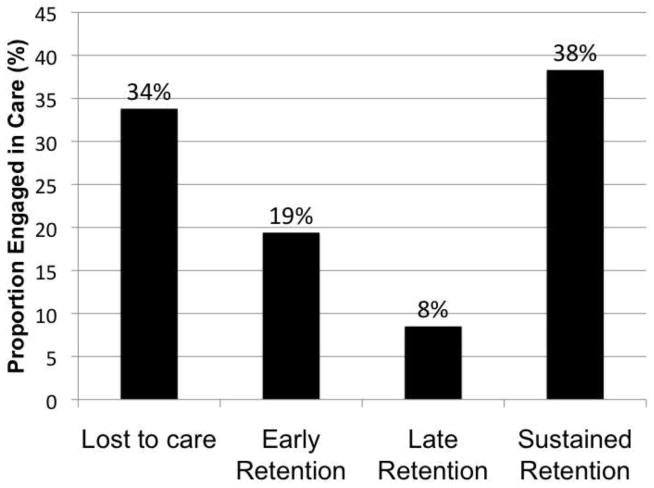

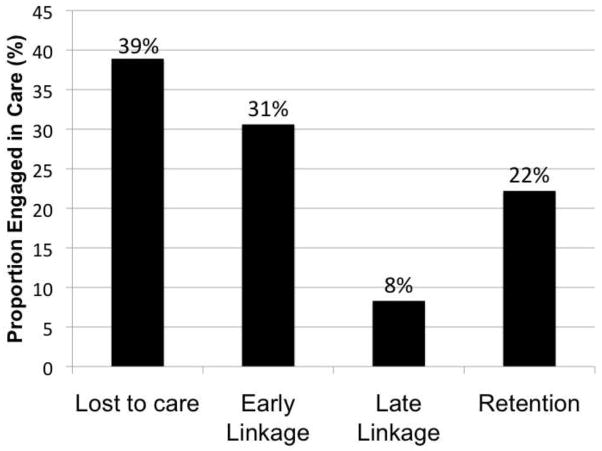

Figure 3 depicts the proportion of participants having met each of the three pre-specified definitions of retention in care (primary outcome). Overall, 34% of the sample was lost to follow-up and 38% had sustained retention in care (HIV provider visits in both the first and second quarters) following release. In addition, among the 36 newly diagnosed participants, 39% had no recorded visits with an HIV provider in the 6-month post-release period, and 22% had sustained retention in care (see Figure 4). Overall, age, race, relationship status, education, and prior homelessness were not significantly associated with retention in care by any definition. Similarly, having health insurance prior to incarceration and taking ART were not predictive of retention.

Figure 3. Proportion of all subjects retained in care (N=867).

Legend: Retention in care is defined as having an HIV provider visit during a specified time period following release from jail: Early = clinic visit in first quarter only; Late = clinic visit in second quarter only; Sustained = clinic visits in both first and second quarters.

Figure 4. Proportion of newly diagnosed subjects linked to care (N= 36).

Legend: Linkage or retention in care is defined as having an HIV provider visit during a specified time period following release from jail. Early Linkage = clinic visit in first quarter only; Late Linkage = clinic visit in second quarter only; Retention = clinic visits in both first and second quarters.

In the early retention model (first quarter) shown in Table II, participants had a higher likelihood of immediate post-release follow-up if they were male, had a regular HIV provider at baseline, and received the following services in the community after release from jail: a needs assessment, one-on-one counseling, and a disease management education session. They were also more likely to follow-up if an appointment was made for them with an HIV provider.

Table II.

Correlates of Visits in the First Quarter (Early Retention) Using Logistic Regression

| Covariates | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio1 | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Age | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Gender: | ||||||

| Male | 2.84 | 2.12–3.81 | <0.01 | 1.84 | 1.27–2.67 | <0.01 |

| Female (Referent) | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity: | ||||||

| White (Referent) | ||||||

| Black | .98 | 0.70–1.38 | 0.19 | |||

| Hispanic | 1.98 | 1.34–2.93 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Other | 0.57 | 0.25–1.31 | 0.18 | |||

| Homeless at baseline | 0.74 | 0.56–0.98 | 0.04 | * | * | * |

| Relationship status: | ||||||

| In a steady relationship | 1.04 | 0.78–1.38 | 0.80 | |||

| Not in steady relationship (Referent) | ||||||

| Education: | ||||||

| Less than high school | 0.78 | 0.58–1.05 | 0.11 | |||

| High school (Referent) | ||||||

| Above high school | 0.87 | 0.57–1.31 | 0.50 | |||

| Reincarcerated | 1.36 | 1.00–1.83 | 0.04 | * | * | * |

| Length of Index incarceration | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.30 | |||

| Health Insurance at baseline | 2.21 | 1.62–3.03 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

|

| ||||||

| HIV Care | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Newly diagnosed HIV + | 0.81 | 0.42–1.59 | 0.55 | |||

| Taking ART within 7 days of incarceration | 1.43 | 1.00–2.01 | 0.04 | * | * | * |

| Adherence to ART >/= 95% | 1.62 | 1.12–2.35 | 0.01 | * | * | * |

| HIV VL<400 at baseline | 1.02 | 0.75–1.38 | 0.91 | |||

| Usual HIV provider at baseline | 2.09 | 1.52–2.86 | <0.01 | 1.66 | 1.09–2.52 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Depression/anxiety | 0.70 | 0.53–0.92 | 0.01 | |||

| Bipolar disorder | 0.75 | 0.50–1.14 | 0.18 | |||

| Known Hepatitis C | 1.65 | 1.24–2.19 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Psychiatric medications | 0.96 | 0.71–1.31 | 0.82 | |||

| Drug use in last 30 days: | ||||||

| Heroin | 1.50 | 1.10–2.05 | 0.01 | 1.49 | 1.00–2.20 | 0.05 |

| Cocaine | 1.01 | 0.77–1.33 | 0.94 | |||

| Alcohol | 0.88 | 0.66–1.19 | 0.42 | |||

| Severe Drug Use | 1.47 | 0.60–3.61 | 0.40 | |||

| Severe Alcohol Use | 0.60 | 0.34–1.08 | 0.09 | * | * | * |

| Severe Psychiatric Illness | 0.57 | 0.34–0.96 | 0.03 | * | * | * |

|

| ||||||

| Services Received | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| During Incarceration: | ||||||

| Needs assessment | 1.58 | 1.16–2.16 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| HIV education | 1.19 | 0.91–1.55 | 0.21 | |||

| Discharge planning | 1.43 | 1.08–1.89 | 0.01 | * | * | * |

| Disease management Session | 1.91 | 1.44–2.55 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Community program contacted Jail | 0.96 | 0.68–1.35 | 0.82 | |||

| After Release: | ||||||

| Needs assessment | 3.16 | 2.38–4.19 | <0.01 | 2.06 | 1.43–2.95 | <0.01 |

| HIV education | 3.01 | 2.21–4.11 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| One-on-one counseling | 2.65 | 2.01–3.49 | <0.01 | 1.90 | 1.32–2.73 | <0.01 |

| Disease management Session | 4.58 | 3.28–6.40 | <0.01 | 2.34 | 1.53–3.58 | <0.01 |

| Transportation | 2.21 | 1.67–2.92 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Accompanied subject to Visit | 2.55 | 1.84–3.52 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Appointment scheduled with: | ||||||

| HIV primary care provider | 4.15 | 3.10–5.54 | <0.01 | 2.38 | 1.67–3.38 | <0.01 |

| Substance abuse Counselor | 3.96 | 2.91–5.40 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Mental health counselor | 3.39 | 2.34–4.90 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Housing coordinator | 3.07 | 2.29–4.11 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Other health specialist | 3.27 | 2.30T–4.64 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Social service provider | 3.25 | 2.44–4.32 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

Variable is excluded from the final multivariate model based on AIC criterion.

Adjusted for each independent variable significant at p<0.10 in the univariate analysis and study site; final model chosen by AIC criterion

Like early retention outcomes, participants were more likely to follow up in the second quarter (late retention) if they were male, had a regular HIV provider at baseline, and had a needs assessment and disease management session following release. In addition, discharge planning during incarceration, having an HIV education session after release, and receiving assistance with transportation were also associated with a higher likelihood of follow-up in the second quarter (see Table III).

Table III.

Correlates of Visits in the Second Quarter (Late Retention) Using Logistic Regression

| Covariates | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio1 | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Age | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Gender: | ||||||

| Male | 2.56 | 1.90–3.46 | <0.01 | 1.82 | 1.27–2.61 | <0.01 |

| Female (Referent) | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity: | ||||||

| White (Referent) | ||||||

| Black | 1.20 | 0.85–1.68 | 0.29 | |||

| Hispanic | 2.04 | 1.40–2.96 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Other | 0.88 | 0.38–2.05 | 0.78 | |||

| Homeless at baseline | 0.72 | 0.54–0.95 | 0.02 | * | * | * |

| Relationship status: | ||||||

| In a steady relationship | 0.95 | 0.72–1.26 | 0.73 | |||

| Not in steady relationship (Referent) | ||||||

| Education: | ||||||

| Less than high school | 0.69 | 0.51–0.93 | 0.02 | * | * | * |

| High school (Referent) | ||||||

| Above high school | 0.84 | 0.56–1.27 | 0.43 | * | * | * |

| Reincarcerated | 1.34 | 1.00–1.79 | 0.05 | * | * | * |

| Length of Index incarceration | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.77 | |||

| Health Insurance at baseline | 1.87 | 1.36–2.57 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

|

| ||||||

| HIV Care | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Newly diagnosed HIV + | 0.49 | 0.24–1.00 | 0.05 | * | * | * |

| Taking ART within 7 days of incarceration | 1.44 | 1.09–1.90 | 0.01 | * | * | * |

| Adherence to ART >/= 95% | 1.81 | 1.28–2.55 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| HIV VL<400 at baseline | 0.88 | 0.64–1.21 | 0.42 | |||

| Usual HIV provider at baseline | 2.20 | 1.59–3.05 | <0.01 | 1.71 | 1.15–2.53 | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Depression/anxiety | 0.64 | 0.49–0.84 | <0.01 | |||

| Bipolar disorder | 0.63 | 0.41–0.96 | 0.03 | * | * | * |

| Known Hepatitis C | 1.51 | 1.15–1.99 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Psychiatric medications | 0.99 | 0.73–1.34 | 0.94 | |||

| Drug use in 30 days prior: | ||||||

| Heroin | 1.18 | 0.87–1.59 | 0.29 | |||

| Cocaine | 0.66 | 0.50–0.86 | <0.01 | 0.74 | 0.53–1.02 | 0.07 |

| Alcohol | 0.82 | 0.61–1.11 | 0.20 | |||

| Severe Drug Use | 0.61 | 0.26–1.45 | 0.27 | |||

| Severe Alcohol Use | 0.56 | 0.31–0.99 | 0.05 | * | * | * |

| Severe Psychiatric Illness | 0.51 | 0.31–0.86 | 0.01 | * | * | * |

|

| ||||||

| Services Received | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| During Incarceration: | ||||||

| Needs assessment | 1.26 | 0.92–1.72 | 0.14 | * | * | * |

| HIV education | 1.17 | 0.90–1.53 | 0.25 | |||

| Discharge planning | 1.48 | 1.12–1.96 | 0.01 | 1.46 | 1.06–2.00 | 0.02 |

| Disease management session | 1.68 | 1.28–2.22 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Community program contacted jail | 0.78 | 0.56–1.10 | 0.16 | |||

| After Release: | ||||||

| Needs assessment | 2.19 | 1.66–2.90 | <0.01 | 1.56 | 1.10–2.21 | 0.01 |

| HIV education | 2.66 | 1.99–3.55 | <0.01 | 1.86 | 1.27–2.71 | <0.01 |

| One-on-one counseling | 1.88 | 1.43–2.47 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Disease management session | 3.14 | 2.33–4.23 | <0.01 | 2.04 | 1.39–2.99 | <0.01 |

| Transportation | 2.00 | 1.53–2.63 | <0.01 | 2.04 | 1.49–2.79 | <0.01 |

| Accompanied subject to visit | 2.04 | 1.51–2.75 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Appointment scheduled with: | ||||||

| HIV primary care provider | 3.14 | 2.35–4.20 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Substance abuse counselor | 3.06 | 2.30–4.07 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Mental health counselor | 2.57 | 1.85–3.58 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Housing coordinator | 2.83 | 2.14–3.75 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Other health specialist | 2.64 | 1.92–3.63 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Social service provider | 2.48 | 1.89–3.27 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

Variable is excluded from the final multivariate model based on AIC criterion.

Adjusted for each independent variable significant at p<0.10 in the univariate analysis and study site; final model chosen by AIC criterion

We also explored correlates of having consistent HIV follow-up using the most stringent definition (sustained retention, or having clinic visits in both the first and second quarters) and that which reflects the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s current guidelines (29): having an HIV clinic visit at least every 3 months (Table IV). Similar to outcomes for early and late retention, being male was associated with a twofold higher likelihood of sustained retention in care (AOR=2.10, CI 1.42–3.11; p<0.01), as was having a regular HIV provider prior to incarceration (AOR= 1.67, CI 1.09–2.56; p=0.02). Receipt of several services was also associated with sustained retention in care: disease management session and discharge planning during incarceration, and a needs assessment, HIV education, and transportation assistance after release (See Table IV). Despite extensive psychiatric, medical, and substance use disorder comorbidities, severity of such diseases alone was not found to significantly impact retention in care. Conversely, heroin use was found to be associated with a higher likelihood of both early (AOR= 1.49, CI 1.00–2.20; p= 0.05) and sustained (AOR= 1.49, CI 1.02–2.19; p= 0.04) retention, but not late retention alone.

Table IV.

Correlates of Visits in Both Quarters (Sustained Retention) Using Logistic Regression

| Covariates | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio1 | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Age | 1.04 | 1.02–1.06 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Gender: | ||||||

| Male | 3.05 | 2.20–4.23 | <0.01 | 2.10 | 1.42–3.11 | <0.01 |

| Female (Referent) | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity: | ||||||

| White (Referent) | ||||||

| Black | 1.20 | 0.84–1.70 | 0.32 | |||

| Hispanic | 2.29 | 1.57–3.35 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Other | 0.62 | 0.24–1.64 | 0.34 | |||

| Homeless at baseline | 0.64 | 0.48–0.85 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Relationship status: | ||||||

| In a steady relationship | 1.00 | 0.75–1.34 | 0.99 | |||

| Not in a steady relationship (Referent) | ||||||

| Education: | ||||||

| Less than high school | 0.72 | 0.54–0.98 | 0.04 | * | * | * |

| High school (Referent) | ||||||

| Above High school | 0.90 | 0.59–1.36 | 0.62 | |||

| Reincarcerated within 6 months | 1.20 | 0.89–1.62 | 0.22 | |||

| Length of Index incarceration | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.86 | |||

| Health Insurance at baseline | 2.40 | 1.69–3.40 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

|

| ||||||

| HIV Care | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Newly diagnosed HIV + | 0.45 | 0.20–0.99 | 0.05 | * | * | * |

| Taking ART within 7 days of incarceration | 1.49 | 1.11–1.99 | <0.01 | |||

| Adherence to ART >/= 95% | 1.48 | 1.06–2.07 | 0.02 | 1.51 | 0.98–2.32 | 0.06 |

| HIV VL<400 at baseline | 0.87 | 0.64–1.18 | 0.37 | |||

| Usual HIV provider at baseline | 2.25 | 1.59–3.17 | <0.01 | 1.67 | 1.09–2.56 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Depression/anxiety | 0.56 | 0.43–0.74 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Bipolar disorder | 0.48 | 0.30–0.77 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Known Hepatitis C | 1.77 | 1.34–2.35 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Psychiatric medications | 0.80 | 0.58–1.10 | 0.17 | |||

| Drug use in 30 days prior: | ||||||

| Heroin | 1.61 | 1.18–2.19 | <0.01 | 1.49 | 1.02–2.19 | 0.04 |

| Cocaine | 0.80 | 0.61–1.06 | 0.12 | |||

| Alcohol | 0.85 | 0.62–1.15 | 0.29 | |||

| Severe Drug Use | 1.20 | 0.49–2.93 | 0.69 | |||

| Severe Alcohol Use | 0.55 | 0.30–1.01 | 0.05 | * | * | * |

| Severe Psychiatric Illness | 0.37 | 0.21–0.63 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

|

| ||||||

| Services Received | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| During Incarceration: | ||||||

| Needs assessment | 1.56 | 1.12–2.17 | 0.01 | * | * | * |

| HIV education | 1.44 | 1.09–1.89 | 0.01 | * | * | * |

| Discharge planning | 1.63 | 1.22–2.19 | <0.01 | 1.50 | 1.06–2.12 | 0.02 |

| Disease management session | 2.14 | 1.61–2.84 | <0.01 | 2.25 | 1.51–3.36 | <0.01 |

| Community program contacted jail | 0.88 | 0.62–1.25 | 0.48 | |||

| After Release: | ||||||

| Needs assessment | 2.50 | 1.86–3.37 | <0.01 | 1.59 | 1.06–2.37 | 0.02 |

| HIV education | 3.24 | 2.42–4.35 | <0.01 | 2.03 | 1.37–2.99 | <0.01 |

| One-on-one counseling | 2.47 | 1.86–3.29 | <0.01 | 1.42 | 0.96–2.10 | 0.08 |

| Disease management session | 4.35 | 3.22–5.89 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Transportation | 2.08 | 1.58–2.75 | <0.01 | 1.54 | 1.06–2.22 | 0.02 |

| Accompanied subject to visit | 2.06 | 1.52–2.78 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Appointment scheduled with: | ||||||

| HIV primary care provider | 3.90 | 2.84–5.34 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Substance abuse counselor | 3.59 | 2.68–4.79 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Mental health counselor | 2.45 | 1.77–3.38 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Housing coordinator | 2.87 | 2.16–3.82 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Other health specialist | 2.94 | 2.15–4.03 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

| Social service provider | 2.63 | 1.98–3.49 | <0.01 | * | * | * |

Variable is excluded from the final multivariate model based on AIC criterion.

Adjusted for each independent variable significant at p<0.10 in the univariate analysis and study site; final model chosen by AIC criterion

Discussion

Retention in care is important in promoting medication persistence after release from jail, which can both improve the health of the individual and decrease transmission of HIV to others. The time surrounding release from jail is often chaotic, and the EnhanceLink project focused on improving this transition to the community for PLWHA and engaging them in HIV care. This is the first analysis to our knowledge to systematically evaluate jail detainees’ retention in HIV care following release, including individuals who systematically received access to an array of services. We use the term retention (divided into early, late, and sustained) given that 74% of participants reported having an HIV provider prior to incarceration and all should have received HIV care during their jail stays.

In our evaluation of 867 newly released jail detainees with HIV across ten different sites, only one-third had sustained retention in care during their first six months in the community. Over one-third did not have any recorded visit with an HIV provider during the study follow-up period, despite opportunities for intensive case management provided by the EnhanceLink program. Importantly, 39% of individuals newly diagnosed with HIV were lost to follow-up. These results fall short of the Department of Health and Human Services recommendation that all PLWHA receive basic preventative care quarterly (30). Of note, the majority of participants were linked to care after release (or had an HIV provider visit within 6 months), which was the primary goal of the Enhancelink program.

It is especially important that HIV-infected jail detainees receive continuous clinical care with an HIV provider, as the time immediately following release from incarceration imparts great risk for engaging in high-risk behaviors including relapse to drug use and unprotected and/or transactional sex (31, 32). These behaviors may be harmful to the individual, who in turn may potentially and unwittingly transmit HIV to others. Recent data suggest that receiving ART, and presumably achieving viral suppression, results in a 96% reduction in sexual transmission of HIV (33), highlighting the importance of HIV medication access and treatment persistence in secondary prevention.

Of the demographic factors (predisposing variables), being male was consistently associated with a 2-fold higher likelihood of being retained in care. In 2009, women represented 25% of newly diagnosed cases of HIV in the US, 80% of infections were sexually transmitted, and minorities were disproportionately represented (66% Black, 14% Latina) (34). Among prisoners, 1.9% of women are infected with HIV compared to 1.5% of men (35). Several recent studies have highlighted disparities for women versus men infected with HIV, (particularly among minority women) including lower rates of receipt of ART (36, 37), higher rates of HIV-related and AIDS-defining events (38), and greater mortality rates (37). Perhaps these disparities can be explained by differences in retention in care for men and women, although recent data regarding rates of follow-up for the two groups are mixed (39, 40). In our evaluation, female HIV-infected jail detainees were 50% less likely than men to be retained in care, which clearly demands a call to better address women’s needs upon discharge from jail.

In previous studies, mental illness has been shown to play an important and detrimental role in a number of HIV-related outcomes, including HIV risk behaviors, access to and adherence to ART, and retention in HIV care. Specifically, in non-incarcerated PLWHA, depression has been found to be closely correlated with poor adherence to ART and clinic appointments (41–43). While depression was highly prevalent among this cohort of jail detainees (56%), it was not found to be significantly correlated with retention in care. Of note, we were limited in our examination of the dynamics of mental illness in this analysis as there was variability among sites in enrollment of those with and without mental illness, and participants were not consistently evaluated in follow-up study instruments.

Substance use disorders are highly prevalent in populations that interface with the criminal justice system: more than two-thirds of the total US jail population reports engaging in regular substance use (44). Importantly, substance use disorders and relapse to drug or alcohol use after release have been found to negatively influence retention in HIV care (41, 45). We found high rates of substance use disorders in our population but, somewhat surprisingly, alcohol use, cocaine use, and severity of addiction were not significantly correlated with retention in care. In contrast to other drugs, heroin use within 30 days of incarceration was associated with a higher likelihood of early and sustained retention. One possible explanation for this finding is coupling of opioid-replacement therapy with HIV care at some sites following release, although this is speculative.

While 69% of participants reported having a mental illness at baseline, only 23% received an appointment for mental health treatment following release. Similarly, while 80% of participants admitted to using drugs or alcohol in the 30 days prior to incarceration, only 38% received an appointment with a substance abuse counselor. Furthermore, having such appointments made for substance abuse and mental health counseling did not significantly affect retention in care in our evaluation. We do not know if all appointments made by case managers were attended, but perhaps referrals alone may be insufficient to result in effective linkages, especially in the context of under or untreated depression or active drug use. Addressing substance use and psychiatric disorders is essential to successful comprehensive HIV treatment, but efforts to do so may be limited by a lack of acceptance by inmates, poor access to care, or both.

This study also evaluated the impact of health behaviors on retention in HIV care following release from jail. While adherence to ART and having an undetectable viral load prior to incarceration were not significantly correlated with retention following release, having an HIV provider at baseline was associated with an increased likelihood of retention in care following release by every definition. This finding may merely reflect that those who are already engaged in care are more likely to remain so due to a multitude of possible factors. However, effectively linking those not already engaged in care, including newly diagnosed detainees, not only provides the potential to improve outcomes for these individuals, but may also increase the likelihood that one remains in care following re-incarceration in the future. Further evaluation of the differences between those already engaged in care and those not engaged prior to incarceration is warranted.

Jail recidivism is very common and poses obvious challenges to engaging and retaining PLWHA in long-term care. Overall, 30% of subjects in this evaluation were re-incarcerated at least once for variable time periods during the six-month follow-up period. Re-incarceration itself was not associated with our outcome of retention in care. Recidivism in other studies, however, has been associated with poor treatment outcomes (8, 46–48). (It is possible that some participants received HIV care during re-incarceration which was not included in our outcome of interest given the fidelity to the intention-to-treat principle.) While incarceration provides a unique opportunity for identifying and treating people with HIV, it has also been associated with virologic failure and poor adherence to ART (46, 47). Time in jail or prison can be disruptive to individuals and communities, and there are corrections-associated barriers to ART adherence which can influence HIV outcomes (47). Such barriers include lack of medical care in short-term holding cells, issues around HIV-associated disclosure and confidentiality, a lack of continuity of care between correctional and community-based clinics (47), and logistical dilemmas encountered once released (i.e. lack of identification, insurance, housing, etc.) (8, 48, 49).

Although this multi-site project linked the majority of participants to HIV care in the community, according to this evaluation, timeliness was lacking, and rates of sustained retention were far from optimal. Our results raise the question: Whose responsibility is it to help retain this population in care? Jail programs? Community providers? We found that receipt of enabling resources (jail and community-based services) was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of follow-up. This positive association was found regardless of age race, education, relationship status, homelessness prior to incarceration, mental illness, and substance use disorders. These findings are consistent with those of the Antiretroviral Treatment and Access Study (ARTAS), which showed that participation in case management sessions was associated with higher follow-up rates (50), and support the newly-released ART adherence guidelines (51). Although provision of case management services has been shown to improve linkage to care (52), according to one study, less than half of 47 state and federal correctional systems and only 39% of 33 large city and county facilities offer such referrals (53, 54). Most prisons and large jails do offer some degree of discharge planning which has been shown to result in greater rates of follow-up among HIV-infected prisoners in prior studies (11), and in jail detainees in our evaluation. Receipt of services occurred prior to HIV provider visits in 57% of cases, which highlights a need to even better understand differences in health behaviors.

There are several limitations to our evaluation. First, given the non-random sample and the observational nature of the assessment, the direction of causation among variables cannot be established. It is possible that sample selection bias contributed to some of the association between independent variables, in particular the use of services, and retention in care outcomes which is likely to be influenced by the unobserved heterogeneity among subjects. In addition, in some cases post-release services were collocated with HIV clinics which could potentially lead to biased results. Second, the high rate of attrition in the evaluation among the subjects constituted a missing data problem, especially for the variables measured in the post-release period. Although our estimates for the missing data were either based on multiple imputation or a conservative assessment based on absence of records, the inability to fully control for the attrition rate may contribute to the selection bias due to an omitted variable problem. Third, some independent variables associated with service use may not have been accurate indicators of service that was planned or delivered. For example, variables measuring access to appointments did not reflect the actual attendance of these appointments. Also, in the absence of scores measuring the quality of services rendered, it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of services. Furthermore, the frequency of receipt of each case management service may not have been fully measured in the instruments we reviewed. Last, as mentioned above, those who were re-incarcerated may have received HIV care in jail, but did not have visits in the community during a specified outcome period. Similarly, it is possible that some participants received care or had VL’s performed elsewhere which were not recorded in this evaluation. In addition, VL’s reported more than seven months after release were not included in the analysis. Each of these factors could have contributed to a falsely lower retention rate than actually occurred. Despite these limitations, the EnhanceLink program is important because it represents the first project both to evaluate linkages to care between jails and communities and to intervene in meaningful ways.

Our results convey promise for this difficult-to-treat population as largely modifiable variables were found to correlate with retention. If the effect of each successful service on retention in care is additive, follow-up rates could potentially be improved dramatically. Although it appears that engagement in community services was beneficial to retention in care, uptake was relatively low. Access to and acceptance of such services should be addressed in future research. In addition, services to specifically address female jail detainees needs upon discharge warrant further study.

Conclusion

Incarceration can provide a unique opportunity to diagnose and treat HIV. Time spent in jails however, is often short and chaotic, making treatment in this setting difficult, and potentially disrupting HIV care. Linkage to and retention in HIV care following release from jail are key to continuing effective HIV treatment, and can be improved through jail and community-based services. More work is needed to effectively and actively engage released jail detainees in community-based and long-term HIV care, a goal that will improve the health of both HIV-infected individuals and the communities to which they return.

Acknowledgments

Enhancing Linkages to HIV Primary Care Services Initiative is a HRSA-funded Special Project of National Significance. Funding for this research was also provided through career development grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K24 DA017072, FLA and K23 DA033858, JPM), research grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA018944, FLA), institutional research training grants from the NIMH (T32 MH020031, JPM) and NIAID (T32 AI007517, ALA). The funding sources played no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advancing HIV Prevention Initiative. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lima VD, Johnston K, Hogg RS, Levy AR, Harrigan PR, Anema A, et al. Expanded access to highly active antiretroviral therapy: a potentially powerful strategy to curb the growth of the HIV epidemic. J Infect Dis. 2008 Jul 1;198(1):59–67. doi: 10.1086/588673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Getting to Zero. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, Crepaz N. Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2010 Nov;24(17):2665–78. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f4b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Suarez-Almazor ME, Rabeneck L, Hartman C, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jun;44(11):1493–9. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen NE, Meyer JP, Avery AK, Draine J, Flanigan TP, Lincoln T, et al. Adherence to HIV Treatment and Care Among Previously Homeless Jail Detainees. AIDS Behav. 2011 Nov; doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0080-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer JP, Chen NE, Springer SA. HIV Treatment in the Criminal Justice System: Critical Knowledge and Intervention Gaps. AIDS Res Treat. 2011:680617. doi: 10.1155/2011/680617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Jun;38(12):1754–60. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Tien HC, Stewart P, Kaplan AH. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Rep. 2005 Jan-Feb;120(1):84–8. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baillargeon JG, Giordano TP, Harzke AJ, Baillargeon G, Rich JD, Paar DP. Enrollment in outpatient care among newly released prison inmates with HIV infection. Public Health Rep. 2010 Jan-Feb;125(Suppl 1):64–71. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, Wu ZH, Wells K, Pollock BH, et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009 Feb;301(8):848–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Harzke AJ, Spaulding AC, Wu ZH, Grady JJ, et al. Predictors of reincarceration and disease progression among released HIV-infected inmates. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010 Jun;24(6):389–94. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pai NP, Estes M, Moodie EE, Reingold AL, Tulsky JP. The impact of antiretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV infected patients going in and out of the San Francisco county jail. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e7115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Draine J, Ahuja D, Altice FL, Arriola KJ, Avery AK, Beckwith CG, et al. Strategies to enhance linkages between care for HIV/AIDS in jail and community settings. AIDS Care. 2011 Mar;23(3):366–77. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Services DoHaH. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1 Infected Adults and Adolescents. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995 Mar;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000 Feb;34(6):1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLellan AT, Cacciola JC, Alterman AI, Rikoon SH, Carise D. The Addiction Severity Index at 25: origins, contributions and transitions. Am J Addict. 2006 Mar-Apr;15(2):113–24. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980 Jan;168(1):26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGahan P, Griffith J, Parente R, McLellan T. Addiction Severity Index Composite Score Manual. The University of Pennsylvania/Veterans Administration Center for Studies of Addiction; [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calsyn DA, Saxon AJ, Bush KR, Howell DN, Baer JS, Sloan KL, et al. The Addiction Severity Index medical and psychiatric composite scores measure similar domains as the SF-36 in substance-dependent veterans: concurrent and discriminant validity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 Nov;76(2):165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Voux A, Spaulding AC, Beckwith C, Avery A, Williams C, Messina LC, et al. Early identification of HIV: empirical support for jail-based screening. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macgowan R, Margolis A, Richardson-Moore A, Wang T, Lalota M, French PT, et al. Voluntary rapid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in jails. Sex Transm Dis. 2009 Feb;36(2 Suppl):S9–13. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318148b6b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackman S. Estimation and inference via Bayesian simulation: anIntroduction to Markov Chain Monte Carlo. American Journal of Political Science. 2000;44:375–404. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manfred J, editor. On Testing the Missing at Random Assumption. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. p. xv.p. 377. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu J, Herme M, Wickersham J, Zelenev A, Althoff A, Zaller N, et al. Understanding the Revolving Door: Factors Associated with Recidivism Among HIV-Infected Jail Detainees. AIDS and Behavior. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aberg JA, Kaplan JE, Libman H, Emmanuel P, Anderson JR, Stone VE, et al. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus: 2009 update by the HIV medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Sep;49(5):651–81. doi: 10.1086/605292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DHHS Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV Infection. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vlahov D, Putnam S. From corrections to communities as an HIV priority. J Urban Health. 2006 May;83(3):339–48. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9041-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, McKaig R, Golin CE, Shain L, Adamian M, et al. Sexual behaviours of HIV-seropositive men and women following release from prison. Int J STD AIDS. 2006 Feb;17(2):103–8. doi: 10.1258/095646206775455775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stone VE. HIV/AIDS in Women and Racial/Ethnic Minorities in the U.S. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012 Feb;14(1):53–60. doi: 10.1007/s11908-011-0226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maruschak L. HIV in Prisons, 2007–2008. U.S. Department of Justice: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones AS, Lillie-Blanton M, Stone VE, Ip EH, Zhang Q, Wilson TE, et al. Multidimensional risk factor patterns associated with non-use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Womens Health Issues. 2010 Sep;20(5):335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lemly DC, Shepherd BE, Hulgan T, Rebeiro P, Stinnette S, Blackwell RB, et al. Race and sex differences in antiretroviral therapy use and mortality among HIV-infected persons in care. J Infect Dis. 2009 Apr;199(7):991–8. doi: 10.1086/597124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meditz AL, MaWhinney S, Allshouse A, Feser W, Markowitz M, Little S, et al. Sex, race, and geographic region influence clinical outcomes following primary HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2011 Feb;203(4):442–51. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Willig JH, Westfall AO, Ulett KB, Routman JS, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Jan;48(2):248–56. doi: 10.1086/595705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall HI, Gray KM, Tang T, Li J, Shouse L, Mermin J. Retention in Care of Adults and Adolescents living with HIV in 13 U.S. Areas. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Jan; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318249fe90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Springer SA, Chen S, Altice F. Depression and symptomatic response among HIV-infected drug users enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of directly administered antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2009 Aug;21(8):976–83. doi: 10.1080/09540120802657555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Oct;58(2):181–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d490a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Traeger L, O’Cleirigh C, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Risk factors for missed HIV primary care visits among men who have sex with men. J Behav Med. 2011 Nov; doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9383-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.James DJ. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002. U.S. Department of Justice; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010 Jul;376(9738):367–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westergaard RP, Kirk GD, Richesson DR, Galai N, Mehta SH. Incarceration predicts virologic failure for HIV-infected injection drug users receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Oct;53(7):725–31. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J, Rhodes T, Guillemi S, Hogg R, et al. Dose-response effect of incarceration events on nonadherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 2011 May;203(9):1215–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Springer SA, Spaulding AC, Meyer JP, Altice FL. Public health implications for adequate transitional care for HIV-infected prisoners: five essential components. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Sep;53(5):469–79. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vlassova N, Angelino AF, Treisman GJ. Update on mental health issues in patients with HIV infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009 Mar;11(2):163–9. doi: 10.1007/s11908-009-0024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, Loughlin AM, del Rio C, Strathdee S, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS. 2005 Mar;19(4):423–31. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, et al. Guidelines for Improving Entry Into and Retention in Care and Antiretroviral Adherence for Persons With HIV: Evidence-Based Recommendations From an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Mar; doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flanigan TP, Kim JY, Zierler S, Rich J, Vigilante K, Bury-Maynard D. A prison release program for HIV-positive women: linking them to health services and community follow-up. Am J Public Health. 1996 Jun;86(6):886–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.6.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammett T, Kennedy S, Kuck S. National Survey of Infectious Diseases in Correctional Facilities” HIV and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. US Department of Justice. Department of Justice; Mar, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaller ND, Fu JJ, Nunn A, Beckwith CG. Linkage to care for HIV-infected heterosexual men in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Jan;52(Suppl 2):S223–30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]