Abstract

One-hundred-thirty-one homeless, substance-dependent MSM were enrolled in a randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of a contingency management (CM) intervention for reducing substance use and increasing healthy behavior. Participants were randomized into conditions that either provided additional rewards for substance abstinence and/or health-promoting/prosocial behaviors (“CM-Full”; n = 64) or for study compliance and attendance only (“CM-Lite”; n = 67). The purpose of this secondary analysis was to determine the affect of ASPD status on two primary study outcomes: methamphetamine abstinence, and engagement in prosocial/health-promoting behavior. Analyses revealed that individuals with ASPD provided more methamphetamine-negative urine samples (37.5%) than participants without ASPD (30.6%). When controlling for participant sociodemographics and condition assignment, the magnitude of this predicted difference increases to 10% and reached statistical significance (p < .05). On average, participants with ASPD earned fewer vouchers for health-promoting/prosocial behaviors than participants without ASPD ($10.21 [SD=$7.02] vs. $18.38 [SD=$13.60]; p < .01). Participants with ASPD displayed superior methamphetamine abstinence outcomes regardless of CM schedule; even with potentially unlimited positive reinforcement, individuals with ASPD displayed suboptimal outcomes in achieving health-promoting/prosocial behaviors.

Keywords: Antisocial Personality Disorder, Substance Use, Contingency Management, Homeless, MSM

1. Introduction

1.1 Antisocial personality disorder and substance abuse

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is an Axis-II personality disorder present in approximately 0.6% of the United States population (Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007) characterized by near-constant pursuit of personal gratification and the pervasive disregard for the rights of others, often manifesting as the eschewal of social norms, deceit, aggression, and lack of empathy/remorse (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). ASPD often first manifests itself as aggressive childhood behavior (Schaeffer, Petras, Ialongo, Poduska, & Kellam, 2003), an antecedent occurrence also common to drug abuse disorders (Petras et al., 2008). Previous studies have demonstrated that a diagnosed psychiatric illness increases risk for a comorbid substance use disorder, and ASPD comes with one of the highest such increases in risk (Compton, Conway, Stinson, Colliver, and Grant, 2005; Mueser et al., 2006).

Diagnosis of ASPD is associated with use of alcohol and illegal drugs (Trull, Jahng, Tomko, Wood, and Sher, 2010), with nearly half of all substance abusers meeting the criteria for diagnosis with ASPD (Messina, Farabee, & Rawson, 2003; Messina, Wish, Hoffman, & Nemes, 2001). ASPD the most common comorbid personality disorder amongst substance abusers (Craig, 2000; Fridell, Hesse, & Billsten, 2006; Verheul, 2001), and people with ASPD have more current and lifetime substance use than people without ASPD (Mueser et al., 2006). Additionally, diagnosis of ASPD is associated with heavier methamphetamine use among users (Lecomte et al., 2010), and among individuals who do seek treatment for their substance abuse, individuals with ASPD are more likely to recidivate into heavy drug use after treatment (Fridell, et al., 2006).

1.2 ASPD and substance abuse treatment

Disease characteristics associated with ASPD (including lack of motivation, disruptiveness, impulsivity, and general disregard for others) may all contribute to lower rates of engagement, retention, and poorer outcomes for individuals undergoing substance abuse treatment (Grella, Joshi, & Hser, 2003). Some evidence suggests that ASPD complicates treatment for substance use disorders (Woody, McClellan, Luborsky, & Obrien, 1985) but the effect of a diagnosis of ASPD on treatment effectiveness is controversial (Fridell, Hesse, & Johnson, 2006). While some research has shown no effect of ASPD diagnosis on treatment/intervention outcomes (Alterman, Rutherford, Cacciola, McKay, & Woody, 1996; Darke, Hall, & Swift, 1994; Gill, Nolimal, & Crowley, 1992; Hernandez-Avila et al., 2000; Messina, Wish, Hoffman, & Nemes, 2002), other studies have shown negative effects (Avants et al., 1999; Cacciola, Alterman, Rutherford, & Snider, 1995; Grella et al., 2003; Kosten, Kosten, & Rounsaville, 1989; Martinez-Raga, Marshall, Keaney, Ball, & Strang, 2002; Wolwer, Burtscheidt, Redner, Schwarz, & Gaebel, 2001) and one study demonstrated a positive effect (Messina et al., 2003). The efficacy of a substance abuse treatment/intervention for individuals with ASPD is likely linked to the kind of substance abuse treatment modality or intervention being applied. ASPD is often accompanied by constant striving for personal gratification (Evans & Sullivan, 1990), causing some to suggest that treatments/interventions based on incentives for participation and adherence may produce superior results among those diagnosed with the disorder (Messina et al., 2003; Vaillant, 1975).

1.3 Contingency management interventions

Contingency management (CM) provides positive reinforcement for targeted operant behaviors, including substance abstinence, thereby providing an incentive for positive behavior change in study participants. CM-based substance abuse interventions for participants with ASPD have shown encouraging results. Some studies have found that participants with ASPD respond equally well to such interventions as those without the condition (Brooner, Kidorf, King, & Stoller, 1998; Silverman et al., 1998) and others have found the participants with ASPD actually respond better to substance use interventions relying on CM (Messina et al., 2003).

Concerns of poor treatment/intervention response are common in studies of the homeless (Brecht, Greenwell, & Anglin, 2005), of substance users (Palmer, et al., 2009), and of those with comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse problems (BootsMiller et al., 1998). CM has been efficacious in such impacted populations, improving study retention, participation, and/or reducing substance use among the homeless (Tracy et al., 2007; Burns, Lehman, Milby, Wallace, & Schumacher, 2010), psychiatric inpatients (Corrigan & Liberman, 1994; Bellack, Bennett, Gearon, Brown, & Yang, 2006), substance abusers (Prendergast, Podus, Finney, Greenwell, & Roll, 2006; Dutra et al., 2008), and homeless, substance-dependent MSM (Reback et al., 2010). CM has shown efficacy for reducing the use of alcohol (Barnett, Tidey, Murphy, Swift, & Colby, 2011), marijuana (Carroll et al., 2006), cocaine (Petry & Alessi, 2010), and methamphetamine (Roll et al., 2006; Lee & Rawson, 2008).

1.4 Methamphetamine use, homelessness, and HIV among MSM

Mental health, substance use, homelessness, and sexual minority status (e.g., men who have sex with men) often share reciprocal and reinforcing relationships with one another. Methamphetamine use among MSM is associated with homelessness (Freeman et al., 2011), increased risk for HIV infection (Shoptaw & Reback, 2006), and the transmission of multidrug-resistant strains of HIV (Urbina & Jones, 2004; Markowitz et al., 2005). Methamphetamine use has been shown to produce a wide range of psychiatric symptoms in users, including increases in psychotic-like symptoms and depression (Zweben et al., 2004) that can create additional obstacles to substance abstinence and/or stable housing. Sexual minority status shares known associations with homelessness (Walls, Hancock, & Wisneski, 2007), higher risks for substance abuse (Hughes, McCabe, Wilsnack, West, & Boyd, 2010), and psychological morbidity (Frisell, Lichtenstein, Rahman, & Långström, 2010). Among MSM, methamphetamine use has been shown to negatively affect symptoms of psychological health, with methamphetamine-dependent MSM showing higher neuroticism, lower openness, lower agreeability, and lower conscientiousness (Solomon, Kiang, Halkitis, Moeller, and Pappas, 2010) than non-methamphetamine using MSM. Homelessness is in turn associated with psychological morbidity and substance abuse (Fazel, Khosla, Doll, & Geddes, 2008), and ASPD in specific increases the risk for substance abuse (Craig, 2000; Fridell, et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2004; Verheul, 2001), homelessness (Mueser et al., 2006), and HIV risk behaviors in substance-using populations (Fridell, Hesse, & Johnson, 2006; Gill et al., 1992). CM interventions have shown efficacy in populations possessing one or more of these health risks and may be particularly effective in populations where many of these same cofactors intersect.

The purpose of this secondary analysis was to assess the effect of ASPD status on the efficacy of a CM intervention providing positive reinforcement to reduce substance use and increase health-promoting/prosocial behaviors among homeless, primarily methamphetamine-dependent MSM. It was hypothesized that participants diagnosed with ASPD at baseline would produce superior methamphetamine abstinence outcomes, and inferior health-promoting/prosocial behavior outcomes, when compared to participants without ASPD. The hypothesis predicting superior methamphetamine abstinence outcomes for participants with ASPD was derived from the findings of a prior study (Messina et al., 2003) which showed that participants with ASPD provided superior stimulant abstinence outcomes during a similar CM intervention. The hypothesis predicting inferior health-promoting/prosocial behavior outcomes for participants with ASPD was logically derived, and based on the nature of the disorder itself, the titular element of which is to eschew prosocial behaviors.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited from a low-intensity, community-based health/risk reduction HIV prevention program serving homeless, substance-using MSM in the Hollywood/West Hollywood area of Los Angeles County. Eligibility requirements included: a) male b) active participants in HIV prevention program, c) at least 18 years of age, d) substance dependent (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV [SCID]- verified), e) non-treatment seeking, f) homeless, and g) self-reported sex with a man in the previous 12 months. Individuals were excluded if they did not meet these criteria, were unable to understand the consent forms, or were determined to require a more intense intervention due to a serious psychiatric condition (including those assessed as being in a current manic or psychotic episode).

Of the 131 study participants, 45 (34.4%) were diagnosed with ASPD at baseline, a rate commensurate with prior studies of substance-dependent populations. Participants’ average age was 36.4 years (SD = 8.7). Most participants were Caucasian/white (53.4%), followed by African American/black (22.9%) and Latino/Hispanic (16.8%). Among the participants who met criterion for ASPD, these relative proportions were reversed, as there were more Latino/Hispanic than African American/black participants who met criteria for an ASPD diagnosis. Participants with and without ASPD did show significant differences in terms of educational attainment, with ASPD participants having on average one less year of formal education (11.9 [SD = 2.0] vs. 12.9 [SD = 2.8]; p < 0.05). Full-time employment over the previous 3 years was uncommon among the ASPD participants (12.2%). There was no significant difference in the distribution of ASPD diagnoses across CM conditions.

2.2 Procedure

Participants were recruited from April 2005 through February 2008 via flyers posted at the research institute’s community site and word of mouth. Following consent, eligible participants completed a baseline assessment that included sociodemographic data, recent and lifetime substance use, and psychiatric condition and history. Participants were then randomized into either the CM-Full or CM-Lite condition. Both conditions consisted of a 24-week intervention period, followed by follow-up assessments at 7-, 9-, and 12-months post-randomization.

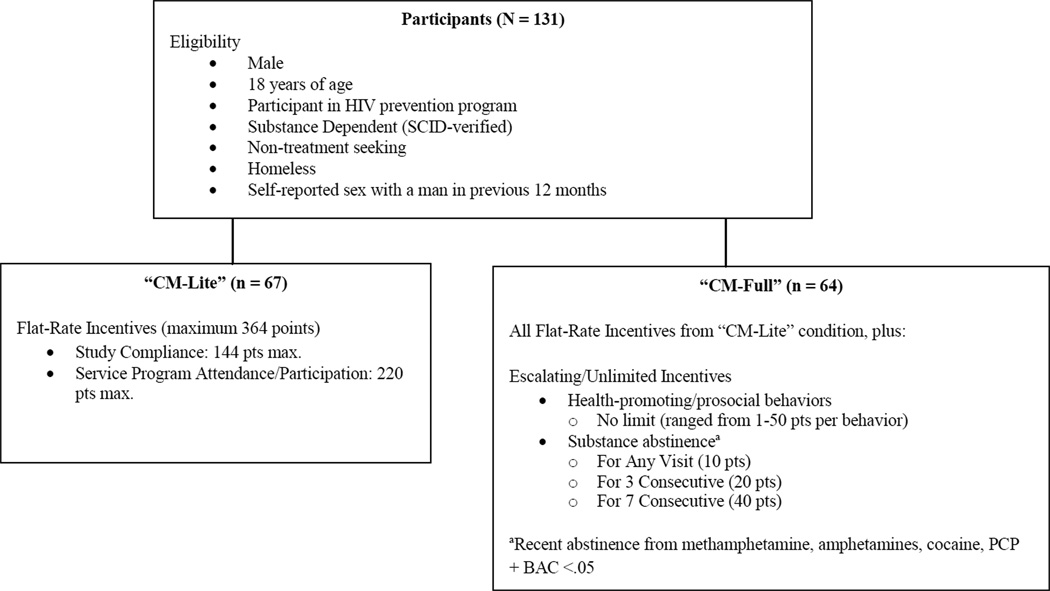

As shown in Figure 1, all participants regardless of condition assignment received positive reinforcement (i.e., earned vouchers) for study compliance and attendance; participants could earn a maximum of 364 vouchers (each equal to $1 in spending power) if they completed all study and service program activities. In addition, those randomized into the “CM-Full” condition, could also earn escalating amounts of vouchers for substance abstinence (as verified through biomarker tests), as well as for engaging in verified health-promoting/prosocial behaviors. Participants earned 10 vouchers for each urine sample provided showing recent abstinence from methamphetamine, amphetamines, cocaine, PCP, and alcohol blood content of less than <0.05, with bonuses of 20 and 40 vouchers at 3- and 7-consecutive clean samples, respectively. Acceptable health-promoting/prosocial behaviors ranged from low impact, easily obtainable goals like scheduling an appointment with a social services agency (4 vouchers); to something more difficult, like enrolling in a GED program (20 vouchers); to high impact, complex behaviors like getting and maintaining a job for 30 days (50 vouchers). Participants reported their behaviors to study staff, and once verified, vouchers were added to the participant’s account. Health-promoting behaviors that could not be verified, such as condom use, were not rewarded. Voucher earnings through health-promoting/prosocial behaviors were potentially unlimited.

Figure 1.

Positive Reinforcement Schedule by CM Condition

All study activities after enrollment occurred at the research institute’s community site, which included an onsite store where participants could redeem their earned vouchers. The site was stocked with participants’ preferred items (as determined by focus groups) to ensure the incentivizing nature of the vouchers. The research institute’s Institutional Review Board provided oversight for all study activities. Additional study procedures and primary outcomes are described elsewhere (Reback et al. 2010).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Participant Sociodemographics

Participant sociodemographics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, HIV status) were recorded at baseline through self-report.

2.3.2 Antisocial personality disorder diagnosis

The SCID-II (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) was administered in paper and pencil form at baseline by trained research staff. Participants meeting criteria for substance dependence in the prior 12 months were deemed preliminarily eligible for study inclusion; the antisocial personality disorder subsection of the SCID-II was further used to identify participants meeting criteria for ASPD.

2.3.3 Methamphetamine use

At all study visits, participants were administered a urine drug screen using a six-panel Food and Drug Administration-approved urine test cup (Accutest, JANT Pharmacal, Inc). Methamphetamine use testing occurred twice weekly on two nonconsecutive days and results were provided to participants during the same visit. Participants could only receive vouchers for abstinence confirmed through urinalysis.

2.3.4 Intervention outcomes

There were two intervention outcome variables: methamphetamine abstinence (as operationalized by methamphetamine-metabolite free urine samples; both conditions, N = 131) and targeted health-promoting/prosocial behaviors (as operationalized by voucher earnings for verified behaviors; “CM-Full” only, n = 64). Methamphetamine abstinence was measured as a proportion; i.e., the number of methamphetamine-metabolite free urine samples provided by a participant was divided by the total number of scheduled urinalyses. As is standard with CM interventions relying on substance abstinent biomarkers, participants with missed urinalyses were considered to be non-abstinent. Participants in the “CM-Full” condition could earn an unlimited amount of vouchers for health-promoting/prosocial behaviors throughout the course of the study; each instance of a participant earning vouchers was included in the random-intercept regression analysis.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic, methamphetamine use, and intervention outcome differences between ASPD and non-ASPD participants at the zero-order level were tested, with the specific method chosen based on the distributional properties of the outcome variable. Additionally, multivariate analyses predicting intervention outcomes while controlling participants’ sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., race/ethnicity, age, education, and HIV status) were carried out. For methamphetamine abstinence, multivariate ordinary least-squares (OLS) analysis regressed the proportion of methamphetamine-metabolite free urine samples provided by the participant on ASPD status, condition assignment, and participant sociodemographics. For targeted health-promoting/prosocial behavior earnings (CM-Full only), a random intercept longitudinal multivariate regression was carried out to determine if ASPD influences behavior earnings while controlling for participant sociodemographics and the autocorrelation occurring within the same participant over time. All statistical tests were carried out using Stata v10SE (StataCorp, 2007), are two-tailed, and significance is reported beginning at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

At baseline, participants’ self-reported substance use in the previous month revealed no significant differences between those with or without ASPD. The most frequently used substances were marijuana, alcohol, and methamphetamine.

Table 2 contains four analyses. Both analyses along the top are bivariate, while both analyses along the bottom are multivariate. Analyses on the left compare methamphetamine abstinence rates across ASPD statuses, while analyses on the right compare health-promoting/prosocial behavior earnings across ASPD statuses. All multivariate models control for race/ethnicity, age, HIV status, educational attainment, and (where necessary) condition assignment.

Table 2.

Associations between ASPD status and intervention response variables

| Methamphetamine abstinence (N = 131) | Behavior earnings (CM-full only; n = 64) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate Z-test for differences in proportions |

Bivariate Student's t-test (unequal variances) |

||||

|

ASPD (n = 45) |

Non-ASPD (n = 86) |

p-value |

ASPD (n = 17) |

Non-ASPD (n = 47) |

p-value |

| 37.5% Methamphetamine- metabolite free urine samples |

30.6% Methamphetamine- metabolite free urine samples |

ns | $10.21 avg/earned per behavior [SD = 7.02] |

$18.38 avg/earned per behavior [SD = 13.60] |

.003 |

| Multivariate Ordinary least squares (OLS) regressiona |

Multivariate Random intercept longitudinal OLS regressionb |

||||

| Predictor | Coef. (SE) | p-value | Predictor | Coef. (SE) | p-value |

| ASPD | 0.10 (0.05) | .04 | ASPD | −$7.80 ($3.20) | .02 |

Controls: race/ethnicity, age, education, HIV status, condition assignment

Controls: race/ethnicity, age, education, HIV status

All sig tests 2-tailed

As shown in Table 2, Participants diagnosed with ASPD at baseline provided an average of 37.5% methamphetamine metabolite-free urine samples during the course of the intervention, compared to 30.6% provided by participants without ASPD, a non-significant difference. When controlling for participant sociodemographics and condition assignment, however, ASPD status was significantly positively associated with methamphetamine abstinence (Coef. = 0.1 [SE =0.05]; p < 0.05), with the magnitude of the difference at the multivariate level increasing from 7% to an estimated 10%. As was reported elsewhere (Reback et al., 2010), the “CM-Full” escalating rewards schedule also produced significant increases in participant abstinence. Separate analyses were carried out to explore the importance of an interaction effect between ASPD status and CM condition. In no instance was the additional interaction effect significant; it was excluded from final analyses to avoid issues of collinearity.

Participants achieved a similar number health-promoting/prosocial behaviors regardless of ASPD diagnosis (MASPD = 28 vs. MNon-ASPD = 23, ns). However, participants with ASPD earned fewer vouchers for health-promoting/prosocial behaviors during the course of the study than participants without ASPD ($221.47 in vouchers [SD = $145.84] vs. $365.53 in vouchers [SD = $493.38], p = .077), implying that, on average, the behaviors enacted by participants with ASPD were of a smaller magnitude than those achieved by participants without ASPD. Thus, to best capture the variance in both the number of behaviors achieved as well as the relative importance of any given behavior, final analyses were conducted on event-level earning data (i.e., actual daily participant voucher earnings throughout the study). As shown in Table 2, at the bivariate level, participants with ASPD earned on average significantly less per behavior than participants without ASPD ($10.21 in vouchers [SD = $7.02] vs. $18.38 in vouchers [SD = $13.60]; p < .01). When controlling for participant sociodemographics, ASPD status retained its significant negative association with health-promoting/prosocial behavior earnings (Coef. = -$7.80 [SE = $3.20]; p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Approximately one-third of participants enrolled in this study were diagnosed with ASPD at baseline. This prevalence rate, although high, is within expected ranges among homeless and substance-dependent populations (Ball, Cobb-Richardson, Connolly, Bujosa, & O’Neall, 2005; Grant et al., 2004; Messina et al., 2003). Although ASPD status shared no association with the frequency of participants’ methamphetamine use at baseline, by intervention completion ASPD status was significantly associated with methamphetamine abstinence. Specifically, after adjusting for the effects of sociodemographics and condition assignment, participants with ASPD achieved a predicted 10% increase in methamphetamine metabolite-free urine samples during the course of the study than participants without ASPD. This corroborates earlier findings that participants with ASPD outperform their counterparts in CM interventions designed to reduce stimulant use (Messina et al., 2003), and supports the first hypothesis. No significant interaction effect between condition assignment and ASPD status was discovered, suggesting the effect of ASPD on methamphetamine abstinence was unique and not moderated by the additional CM voucher earning opportunities in the “CM-Full” condition.

The improvements in methamphetamine abstinence evidenced by the participants diagnosed with ASPD were significantly greater than those displayed by non-ASPD participants across both arms of the study. As has been suggested previously (Vaillant, 1975; Evans & Sullivan, 1990), behavioral programs offering incentives for study-related activities may produce superior outcomes among participants with ASPD. Providing incentives for targeted behaviors may allow pursuit of personal gratification to be made in the service of healthy behavior change. In this study, all participants received the “flat-rate” incentives contingent upon basic study attendance and compliance (Figure 1). Study activities were explicitly focused on the topics of HIV prevention, harm reduction, substance abstinence, and healthy behavior change. Study findings suggest that even minimal, non-escalating incentives appear to be of sufficient magnitude to positively influence the methamphetamine use outcomes of participants with ASPD. This has important implications for program providers working with ASPD-diagnosed individuals within resource-scarce environments.

In sharp contrast to increased methamphetamine abstinence, participants with ASPD earned significantly fewer vouchers for health-promoting/prosocial behaviors than participants without ASPD, earning on average about $8 less per earning event (a difference equivalent to something between a “small” and “medium” health-promoting/prosocial behavior). This finding supports the second hypothesis, and corroborates the known etiology of the disease itself, the titular element of which is the tendency to eschew normative, prosocial behavior. The results presented here imply that although interventions relying on positive reinforcement may be efficacious in reducing methamphetamine use in participants with ASPD, they may not have sufficient power to overcome the behavioral issues that characterize ASPD. In short, voucher-based CM interventions appear to be effective for reducing methamphetamine use in individuals with ASPD even with minimal reinforcement. However, study findings also suggest that the relative incentivizing power of such interventions are not sufficient to increase health-promoting/prosocial behaviors, even when such behaviors are directly targeted with potentially unlimited positive reinforcement.

This secondary analysis is limited by the design and intent of the parent study. In addition to the relatively small sample size, the generalizability of the findings is limited by the specialized population under study (i.e., homeless, non-treatment seeking, substance-dependent MSM enrolled in an urban HIV prevention program). Additionally, given their collinearity with abstinence outcomes in CM interventions, differences in study retention by ASPD status were not directly assessed by this secondary analysis. Future investigations may look to assess the efficacy of CM to increase retention among individuals diagnosed with ASPD. This study is also limited by the lack of statistical control for mental health issues arising during the intervention period. Though potential participants were administered the SCID at baseline, and were excluded from enrollment if they exhibited signs of mental health distress requiring a higher level of care, it is possible that emergent or non-obvious forms of psychological distress may have risen during the intervention that affected substance use outcomes. Lastly, the lack of health-promoting/prosocial behavior data for participants randomized into the “CM-Lite” condition erodes the achieved power of the second hypothesis test and prevents us from determining whether the addition of the increased voucher incentives in the CM-Full condition moderates the effect of ASPD on these behaviors.

4.1 Conclusions

ASPD has traditionally been associated with poorer substance use outcomes, yet recent evidence has shown that participants with ASPD may respond better to CM interventions designed to reduce stimulant use than participants without ASPD. The results of this study replicate previous findings (Messina et al., 2003) by demonstrating that participants diagnosed with ASPD at baseline achieved significantly higher proportional methamphetamine abstinence than their non-ASPD diagnosed counterparts. These results also extend upon current knowledge in two ways: First, these findings suggest that even minimal positive reinforcement (i.e., vouchers for attendance/compliance only) can produce superior methamphetamine use outcomes for participants with ASPD. This finding has broad implications for the adaptation of CM for dually diagnosed participants in a resource limited environment while maintaining maximal impact. Second, the results reported here extend the above-referenced prior findings by revealing that participants with ASPD earned significantly fewer vouchers for health-promoting/prosocial behaviors over the course of the study. This finding established an important scope condition on the efficacy of interventions providing positive reinforcement for targeted behaviors, and provides a cautionary addendum to the encouraging finding that CM interventions produce enhanced methamphetamine abstinence outcomes in participants with ASPD.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics by ASPD status

| Non-ASPD (N = 86) |

ASPD (N = 45) | Total (N = 131) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic |

Mean (SD) or N (%) |

Mean (SD) or N (%) |

Mean (SD) or N (%) |

|

| Age | Years | 36.5 (9.2) | 36.1 (7.8) | 36.4 (8.7) |

| Race/ethnicity∘ | ||||

| Caucasian/White | 44 (51.2%) | 26 (57.8%) | 70 (53.4%) | |

| African | ||||

| American/Black | 23 (26.7%) | 7 (15.6%) | 30 (22.9%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 14 (16.3%) | 8 (17.8%) | 22 (16.8%) | |

| Multi-racial/other | 5 (5.8%) | 4 (8.9%) | 9 (6.9%) | |

| Education | Years | 12.9 (2.9)* | 11.9 (2.0)* | 12.6 (2.6) |

| Employment (past 3 years) | ||||

| Full-time | 10 (11.6%) | 6 (13.3%) | 16 (12.2%) | |

| HIV status | ||||

| HIV+ | 25 (29.1%) | 12 (26.7%) | 37 (28.2%) | |

| Intervention condition | ||||

| CM-lite | 39 (45.3%) | 28 (62.2%) | 67 (51.1%) | |

| CM-full | 47 (54.7%) | 17 (37.8%) | 64 (48.9%) | |

Fisher's Exact tests used due to small cell sizes.

p ≤ .05; All significance tests 2-tailed

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by NIDA Grant RO1 DA015990. Funding for the HIV prevention program was provided by Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Office of AIDS Programs and Policy Contract H-700861. Dr. Reback acknowledges additional support from the National Institute of Mental Health (P30 MH58107). The authors would also like to thank Christine Grella, Ph.D. for her help and guidance in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alterman AI, Rutherford MJ, Cacciola JS, McKay JR, Woody GE. Response to methadone maintenance and counseling in antisocial patients with and without major depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1996;184:695–702. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199611000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Avants SK, Margolin A, Sindelar JL, Rounsaville BJ, Schottenfeld R, Stine S, Kosten TR. Day treatment versus enhanced standard methadone services for opioid-dependent patients: a comparison of clinical efficacy and cost. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:27–33. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Cobb-Richardson P, Connolly AJ, Bujosa CT, O’Neall TW. Substance abuse and personality disorders in homeless drop-in center clients: symptom severity and psychotherapy retention in a randomized clinical trial. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2005;46:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Tidey J, Murphy JG, Swift R, Colby SM. Contingency management for alcohol use reduction: a pilot study using a transdermal alcohol sensor. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, Bennett ME, Gearon JS, Brown CH, Yang Y. A randomized clinical trial of a new behavioral treatment for drug abuse in people with severe and persistent mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:426–432. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootsmiller BJ, Ribisl KM, Mowbray CT, Davidson WS, Walton MA, Herman SE. Methods of ensuring high follow-up rates: lessons from a longitudinal study of dual diagnosed participants. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33:2665–2685. doi: 10.3109/10826089809059344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht M-L, Greenwell L, Anglin MD. Methamphetamine treatment: trends and predictors of retention and completion in a large state treatment system (1992–2002) Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooner RK, Kidorf M, King VL, Stoller K. Preliminary evidence of good treatment response in antisocial drug abusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;49:249–260. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns MN, Lehman KA, Milby JB, Wallace D, Schumacher JE. Do PTSD symptoms and course predict continued substance use for homeless individuals in contingency management for cocaine dependence? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:588–598. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, Rutherford MJ, Snider EC. Treatment response of antisocial substance-abusers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1995;183:166–171. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199503000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Easton CJ, Nich C, Hunkele KA, Neavins TM, Sinha R, Rounsaville BJ. The use of contingency management and motivational/skills-building therapy to treat young adults with marijuana dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:955–966. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Colliver JD, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of DSM-IV antisocial personality syndromes and alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(6):677–685. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Liberman RP, editors. Behavior therapy in psychiatric hospitals. New York, NY: Springer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Craig RJ. Prevalence of personality disorders among cocaine and heroin addicts. Substance Abuse. 2000;21:87–94. doi: 10.1080/08897070009511421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Hall W, Swift W. Prevalence, symptoms and correlates of antisocial personality-disorder among methadone-maintenance clients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;34:253–257. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K, Sullivan J. Dual diagnoses: counseling mentally ill substance abusers. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5(12):e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders - patient edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0, 4/97 revision) 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Freeman P, Walker BC, Harris DR, Garofalo R, Willard N, Ellen JM Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions 016b Team. Methamphetamine use and risk for HIV among young men who have sex with men in 8 US cities. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:736–740. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridell M, Hesse M, Billsten J. Criminal behavior in antisocial substance abusers between five and fifteen years follow-up. American Journal on Addictions. 2006;16:10–14. doi: 10.1080/10550490601077734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridell M, Hesse M, Johnson E. High prognostic specificity of antisocial personality disorder in patients with drug dependence: results from a five-year follow-up. American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:227–232. doi: 10.1080/10550490600626440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisell T, Lichtenstein P, Rahman Q, Långström N. Psychiatric morbidity associated with same-sex sexual behaviour: influence of minority stress and familial factors. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:315–324. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill K, Nolimal D, Crowley TJ. Antisocial personality-disorder, HIV risk behavior and retention in methadone-maintenance therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1992;30:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(92)90059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan J, Pickering RP. Cooccurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Joshi V, Hser YI. Followup of cocaine-dependent men and women with antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:155–164. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Avila CA, Burleson JA, Poling J, Tennen H, Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR. Personality and substance use disorders as predictors of criminality. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2000;41:276–283. doi: 10.1053/comp.2000.7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction. 2010;105:2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ. Personality-disorders in opiate addicts show prognostic specificity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1989;6:163–168. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(89)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte T, Mueser KT, MacEwan WG, Laferrière-Simard M-C, Thornton AE, Buchanan T, Honer WG. Profiles of individuals seeking psychiatric help for psychotic symptoms linked to methamphetamine abuse: baseline results from the MAPS (methamphetamine and psychosis study) Mental Health and Substance Use. 2010;3:168–181. [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK, Rawson RA. A systematic review of cognitive and behavioural therapies for methamphetamine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:309–317. doi: 10.1080/09595230801919494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz M, Mohri H, Mehandru S, Shet A, Berry L, Kalyanaraman R, Ho DD. Infection with multidrug resistant, dual-tropic HIV-1 and rapid progression to AIDS: a case report. Lancet. 2005;365:1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Raga J, Marshall EJ, Keaney F, Ball D, Strang J. Unplanned versus planned discharges from in-patient alcohol detoxification: retrospective analysis of 470 first-episode admissions. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2002;37:277–281. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina N, Farabee D, Rawson R. Treatment responsivity of cocaine-dependent patients with antisocial personality disorder to cognitive-behavioral and contingency management interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:320–329. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina N, Wish E, Hoffman J, Nemes S. Diagnosing antisocial personality disorder among substance abusers: the SCID versus the MCMI-II. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:699–717. doi: 10.1081/ada-100107663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina N, Wish ED, Hoffman JA, Nemes S. Antisocial personality disorder and TC treatment outcomes. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:197–212. doi: 10.1081/ada-120002970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Crocker AG, Frisman LB, Drake RE, Covell NH, Essock SM. Conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder in persons with severe psychiatric and substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:626–636. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, Murphy MK, Piselli A, Ball SA. Substance user treatment droop from client and clinician perspectives: a pilot study. Substance Use and Misuse. 2009;44:1021–1038. doi: 10.1080/10826080802495237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petras H, Kellam SG, Brown CH, Muthen BO, Ialongo NS, Poduska JM. Developmental epidemiological courses leading to antisocial personality disorder and violent and criminal behavior: effects by young adulthood of a universal preventive intervention in first- and second-grade classrooms. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:S45–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM. Prize-based contingency management is efficacious in cocaine abusers with and without recent gambling participation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reback CJ, Peck JA, Dierst-Davies R, Nuno M, Kamien JB, Amass L. Contingency management among homeless, out-of-treatment men who have sex with men. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Huber A, Sodano R, Chudzynski JE, Moynier E, Shoptaw S. A comparison of five reinforcement schedules for use in contingency management-based treatment of methamphetamine abuse. The Psychological Record. 2006;56:67–81. Retrieved from: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/tpr/vol56/iss1/5. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer CM, Petras H, Ialongo N, Poduska J, Kellam S. Modeling growth in boys’ aggressive behavior across elementary school: links to later criminal involvement, conduct disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:1020–1035. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Reback CJ. Associations between methamphetamine use and HIV among men who have sex with men: a model for guiding public policy. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:1151–1157. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Wong CJ, Umbricht-Schneiter A, Montoya ID, Schuster CR, Preston KL. Broad beneficial effects of cocaine abstinence reinforcement among methadone patients. Journal of Consuting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:811–824. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon TM, Kiang MV, Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Pappas MK. Personality traits and mentalhealth states of methamphetamine-dependent and methamphetamine non-using MSM. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(2):161–163. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2007. Stata statistical software: release 10. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy K, Babuscio T, Nich C, Kiluk B, Carroll KM, Petry NM, Rounsaville BJ. Contingency management to reduce substance use in individuals who are homeless with co-occurring psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:253–258. doi: 10.1080/00952990601174931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina A, Jones K. Crystal methamphetamine, its analogues, and HIV infection: medical and psychiatric aspects of a new epidemic. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;38:890–894. doi: 10.1086/381975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE. Sociopathy as a human process: a viewpoint. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1975;32:178–183. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760200042003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R. Co-morbidity of personality disorders in individuals with substance use disorders. European Psychiatry. 2001;16:274–282. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls NE, Hancock P, Wisneski H. Differentiating the social service needs of homeless sexual minority youths from those of non-homeless sexual minority youths. Journal of Children and Poverty. 2007;13:177–205. [Google Scholar]

- Wolwer W, Burtscheidt W, Redner C, Schwarz R, Gaebel W. Out-patient behaviour therapy in alcoholism: impact of personality disorders and cognitive impairments. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;103:30–37. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody GE, Mclellan AT, Luborsky L, Obrien CP. Sociopathy and psychotherapy outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:1081–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790340059009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweben JE, Cohen JB, Christian D, Galloway GP, Salinardi M, Parent D. Psychiatric Symptoms in Methamphetamine Users. The American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13(2):181–190. doi: 10.1080/10550490490436055. Methamphetamine Treatment Project. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]