Abstract

The highly organized DNA architecture inside of the nuclei of cells is accepted in the scientific world. In the human genome about 3 billion nucleotides are organized as chromatin in the cell nucleus. In general, they are involved in gene regulation and transcription by histone modification. Small chromosomes are localized in a central nuclear position whereas the large chromosomes are peripherally positioned. In our experiments we inserted fusion proteins consisting of a component of the nuclear lamina (lamin B1) and also histone H2A, both combined with the light inducible fluorescence protein KillerRed (KRED). After activation, KRED generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) producing toxic effects and may cause cell death. We analyzed the spatial damage distribution in the chromatin after illumination of the cells with visible light. The extent of DNA damage was strongly dependent on its localization inside of nuclei.

The ROS activity allowed to gain information about the location of genes and their functions via sequencing and data base analysis of the double strand breaks of the isolated DNA. A connection between the damaged gene sequences and some diseases was found.

Keywords: Chromatin architecture; DNA-topology, fluorescent proteins; genome architecture; KillerRed; Photo-Dynamic-Therapy; subcellular localization.

Introduction

The decryption of the human genome sequences in 2001 was the jump start for the rapidly expanding genome research 1, 2. Despite of the gained genomic data of bioinformatics, it is difficult to understand the operating mode of the complex genome. Speculations suggested a critical role of a DNA's spatial patterns in the coordination of transcription 3-6. Investigations regarding the development of models of chromosome arrangements go back to the turn of the 20th century, first documented in 1885 by Rabl and in 1909 by Boveri 7, 8. The pioneering work of the Cremer groups in 1996 and 2006 contributed to the acquirement of data reflecting the topologic organization of the genome and of the core principle of the nuclear architecture with functional genome organization 9-11. Meanwhile the highly organized DNA architecture inside of nuclei is considered as accepted in the scientific world 12-15. Localization studies of human chromosomes indicate a central nuclear position of small chromosomes whereas the large chromosomes are peripherally positioned 16. The well investigated basic structural 10 nm fiber is composed of nucleosomes consisting of histone octamers built up of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 acting as structural proteins with DNA wrapped around and histone H1 in the internucleosomal region 17-20. Furthermore, the limited capacity of the volume of the nuclei requires a compact DNA packing with well-regulated chromatin structures like fibers of different size.

Several groups documented gene regulation processes controlled by histone acetylation and deacetylation which are supposed to be independent of the gene localization inside of the nuclei 21-23. The correlation of the nuclear organization of chromosomes to their banding patterns was well documented 24, 25 and comprehensively reviewed and discussed by Santoni 26. The spatial arrangement of genes, centromeres and chromosomes inside nuclei and their changes are documented 27, 28. The inner surface of the nuclear envelope is lined with the nuclear lamina (thickness ~30-100 nm) consisting of components like the lamin B1 protein 29, 30. Its function is critical in gene regulation 31-34 and a change can result in different clinical pictures like the Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy pathophysiology 35, the Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome 36 and further laminopathic diseases 37. However, to which extent these illness patterns could be fostered and caused in cells by cell-externally and -internally induced degenerative processes remains to be investigated.

The impact of reactive oxygen species (ROS) on biological systems was intensively investigated. The meaningful role of free radicals in processes leading to cellular stress causing genetic pathogenesis, like aging, Alzheimer's disease, arteriosclerosis and cancer, as well as inflammatory processes, are without contradiction. Genetoxic effects by external stimuli could also be generated by photolysis effects of light inducible fluorescence proteins (FPs) 38 like KillerRed (KRED). They produce oxygen-generated ROS, like the radicals O2•-, the highly reactive hydroxyl-radical OH•, the peroxide radical ROO•, as well as the active oxygen species (singlet-oxygen 1O2). Disregarding parameters like the concentration gradient and the continuity equation, the self-diffusion of water with the coefficients 3.94×10-9 m2 × s-1 at 50°C; 2.29×10-9 m²·× s-1 at 25°C and 1.26×10-9 m²·× s-1 at 4°C 39 underlies the Brownian motion as a fluctuation phenomenon according to the mean squared displacement (MSD) 40-43. This indicates a very short-range of the ROS's average path length and thus a very small spatially limited sphere of action (~0.1 µm ø).

The ultra-short-lived (~1 µs) singlet oxygen and the superoxide 44, 45 were investigated by the Bulina group 46. These toxic effects may cause cell death as observed in our illumination studies of DU 145 human prostate cancer cells 47 after transfection with the recombinant KRED-lamin B1 plasmid 48. The KRED plasmid and the corresponding protein were first described by the Bulina and Lukyanov groups 46, 49. The protein showed cell toxicity after transfection/transformation and cells' exposition to visible light. The extent of damage was cell type independent 48, 50, but strongly dependent on the localization inside of cells 51 and more precisely, in specific intranuclear positions, as site of action of the activated KRED protein.

Based on Cremer's postulation, mentioned above, and the high cell damaging potential of KRED by visible light, the ROS induced double strand breaks in the DNA should happen close to the lamin-“marbleized” inner surface of the nuclear envelope. The question of the affected genes remains to be answered. Therefore we isolated DNA from DU 145 cell nuclei after transfection or transformation and cloning the cells with the KRED-lamin B1 plasmid. The nuclei were isolated and illuminated with white light with a wave length above 400 nm. As a control organism we used nuclei of the same cell line transfected with the identical plasmid but coding for histone H2A-KRED. The DNA fragments were isolated, sequenced and the affected genes were identified. We used the Illumina Library preparation and sequencing methodology, and characterized sequences with the HUSAR software tools 52. We identified 24,502 genes (offering read counts between 6,824-1) in the KRED-lamin B1 probe harvested 30 min after light illumination and 24,300 genes (offering read counts between 6,039-1) in the KRED-lamin B1 probe 60 min after light illumination of the KRED-lamin B1 transfected DU 145 cells. In the probe with the histone H2A-KRED transfected cells 25,870 affected genes (offering read counts between 15,664-1) were detected 30 min after illumination.

The KRED-lamin B1 probes were investigated at two time points to control the whole procedure. The values were compared to histone H2A-KRED with a wide nuclear distribution.

Material & Methods

Plasmid vectors constructions

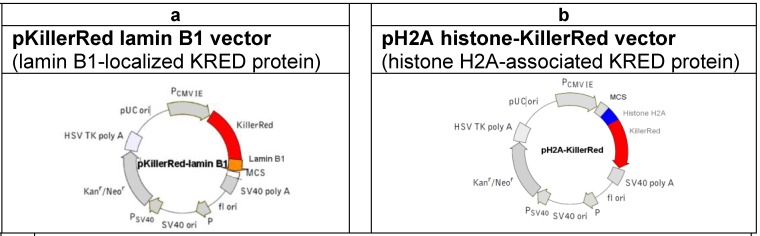

For the investigation of the KRED-induced DNA damage we used the following vectors (Figure 1) coding for the fusion proteins KRED-lamin B1 and histone H2A-KRED 51.

Fig 1.

(a) Physical map of the vector expressing the fusion protein KRED-lamin B1. The lamin B1

was inserted into the MCS. (The lamin B1 sequence was kindly provided by H. Herrmann, this institute). (b) Physical map of the vector expressing the histone fusion protein H2A-KRED. The histone H2A

was inserted into the MCS. (The lamin B1 sequence was kindly provided by H. Herrmann, this institute). (b) Physical map of the vector expressing the histone fusion protein H2A-KRED. The histone H2A

was inserted into the MCS.

was inserted into the MCS.

Cell culture

The stable cell line was established after transfection of the KRED-lamin B1 expressing vector (Supplementary Material: Figure 1a) followed by cloning of positive cells for some weeks. The KRED-lamin B1 transfected cells were gained under selective pressure with G-418. To create a histone-KRED expressing cell line the histone-H2A-KRED vector (Supplementary Material: Figure 1b) had to be transiently expressed; no cell line could be established because of cell death. Both, DU 145 human prostate cancer cells expressing the fusion proteins were cultured and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with FCS 10% (Biochrom, Germany) and L-glutamin 200 mM (Biochrom, Germany) at 37°C in a humid 5% CO2 atmosphere. For the experiments the cells were seeded into Petri dishes (5 × 150 cm2), and were washed with HBSS (Hank's balanced salt concentration, PAN, Germany). After trypsinization of the cells (3 × 106) they were harvested in RPMI 1640 (Gibco 11835) with 2% FCS and centrifuged (800 rounds/min, 5 minutes; Heraeus, Germany). After resuspension of the cells in HBSS the cell number was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells × ml-1 with the DNA repair inhibitor ABT-888 53 (5 µM) HBSS. The extraction of nuclei followed.

Transfection

DU 145 human prostate cancer cells (1.2 × 106 cells in 3 Petri dishes/10 cm diameter) were transfected with the both plasmids according to Invitrogen's user manual. Clones were generated over weeks by selection pressure in cell culture with G-418 (Geneticin®) 500 µg/ml final concentration. With the fusion plasmid (H2A-KRED) transfected cells no cell line could be established, the cells were harvested around 48 - 72 h after transfection.

Isolation of the cell nuclei

This procedure was accomplished completely on ice. All reaction solutions contained the PARP inhibitor ABT-888 (5 µM). After cell trypsinization the cell pellet was washed with HBSS (PAN P04-49505) first, then with isotonic Tris (137 mM NaCl; 5mM KCl; 0.3 mM Na2HPO4×2H2O). After a final wash step with isotonic HEPES buffer [2-(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinyl)-ethane sulfonic acid] 50 mM / pH8; 220 mM sucrose; 0.5 mM CaCl2; 5mM MgCl2 the nuclei were pelleted (1,000 rounds/ min, 5 minutes in a centrifuge, Heraeus Germany). The nuclei were resuspended in 10 ml isotonic HEPES supplemented with 10% NP40, final concentration 0.25%, then vortexed in steps 60s first, followed by three steps à 30s with intervals for 30s on ice. The solution was adjusted to 50 ml with isotonic HEPES. After the next centrifugation (2,000 rounds/ min, 5 minutes; Heraeus, Germany) and resuspension of the pellet in 25 ml solution of isotonic HEPES endued with 200 mM sucrose and 5 µM ABT-888, the nuclei were prepared for illumination studies.

Illumination of the KRED transfected nuclei

The probes with the aforementioned suspensions of the DU 145 cells' nuclei (1 × 106) × ml-1 were placed in Petri dishes with glass bottom (ibidi uncoated) under a full-spectrum sunlight bulb with 32 Watt (www.androv-medical.de) in a distance of 1 cm.

The illumination took place at 20°C; the probes were placed on an aluminium block, cooled by a fan to keep the room temperature. The 32 Watt bulb has a measured intensity of 20,000 lux in a 1cm distance, which reflects a normal daylight in a cloudy summer 54. As determined in earlier experiments, we used the two illumination times: 30 minutes for the measurements of the H2A-KRED probes and for the KRED-lamin B1 probes also 60 min.

DNA isolation - RNase treatment

To avoid RNA contamination of our DNA fragments an enzymatic treatment of the nuclei with RNase was conducted immediately after illumination. The probes were centrifugated (10,000 rounds/min; 10 minutes). The nuclei were resuspended in 300 µl solution of 20 mM Tris (pH8) with 50 µg × ml-1 RNase for 5h and incubated at 37°C and at room temperature overnight. An additional treatment with a 50 µg × ml-1 Proteinase K /0.1% SDS mixture, at 37°C for 5 h and overnight followed to isolate the DNA.

Freeze and squeeze the DNA fragments

The isolated DNA was precipitated with ethanol (70%) and washed twice. Then the DNA fragments were purified in a preparative electrophoresis through an agarose gel in a TAE 1% (Tris-acetate-EDTA) buffer (Figure 2). Small molecules with the most DSB-hits were selected (200 -1,000 bp) with selection of the corresponding DNA sizes by marker bands. The agarose piece was cut out without ethidium bromide and UV light and subsequently frozen at -20°C for at least 1 h followed by centrifugation (3,000 rounds × min-1) at 15°C in 50 ml purification cartridges (Falcon) to isolate the DNA. The complete removal of solvent was terminated after 90 min centrifugation. The probes were concentrated in Centricon-10 cartridges (Millipore, USA) by centrifugation at 15°C and 5,500 rounds × min-1 for 10 min, and then washed in 10 mM Tris pH7, 0.1 mM EDTA before sequence analysis.

Fig 2.

depicts the preparative DNA gel with the lanes containing the DNA fragments for sequencing (white framed). The right lane represents the marker DNA sequence bands; (bp = base pair; M = DNA-marker).

Illumina Library Construction and Sequencing

The fragmented DNA was size selected in a range of 200 - 500 bp using E-Gel® Electrophoresis System and appropriate 1% E-Gel® Ex precast agarose gel (Invitrogen, Cat No. G4010-01) (Figure 2). DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels according to the QIAquick® Gel Extraction Kit protocol (Qiagen, Cat No. 28704) and the DNA quantified using Qubit® flourometer (Invitrogen, Qubit® dsDNA HS Assay Kit, Cat No. Q32854). We started with 450 ng of each probe. Illumina Libraries were prepared using 10 ng of size selected DNA and the NEBNEXT® ChIP-Seq Library Prep Master Mix Set for Illumina (Cat No. E6240L) following the instructions of the manufacturer with the following modifications. We performed a PCR with 3 µL of adapter ligated DNA and 10 amplification cycles. Illumina Libraries were validated using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer® (High sensitivity DNA Kit, Cat No. 5067-4626) and Qubit® flourometer (Invitrogen, Qubit® dsDNA HS Assay Kit).

The final libraries were clustered on the cBot (Illumina) according to the instructions of the manufacturer with a final concentration of 9 pM spiked with 1% ΦX control v3 (Cat No. FC-110-3001) using TruSeq SR Cluster Kit v3 (Cat No. GD-401-3001). Sequencing on HiSeq2000 (51 bp single read mode) was performed using standard Illumina protocols and the 50 cycles TruSeq SBS Kit v3 (Cat No. FC-401-3002).

Bioinformatic treatment of the sequences

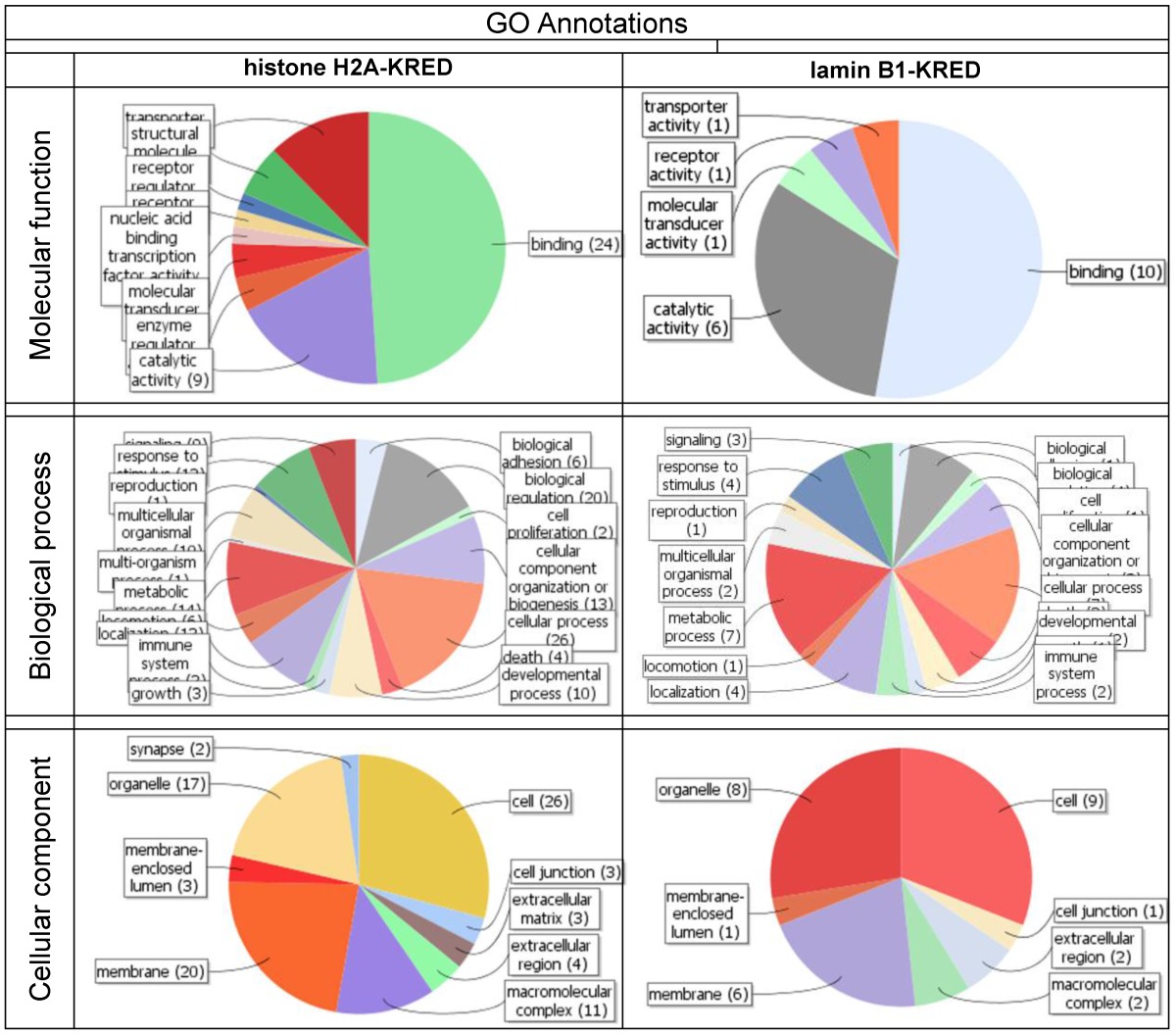

The significant annotation clusters of the 100/600 affected genes were packaged (100-genes bundles). The normalized data (Benjamini & best p-values; cut off at 1.0E-3) are represented in Table 2. The graphical determination and illustration of the KRED-lamin B1 and the H2A-KRED damaged genes as genetic groups following GO annotations are shown in Table 7. We used the Blast2GO tool (http://www.blast2go.com/b2glaunch) for functional annotation of FASTA nucleotide sequences (http://husar.dkfz-heidelberg.de/menu/w2h/w2hdkfz/). BLAST identifies homologous sequences. MAPPING retrieves GO terms. ANNOTATION performs reliable GO functions and enrichment scores. ANALYSIS produces the graphical display of annotation data with GO graphs (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim).

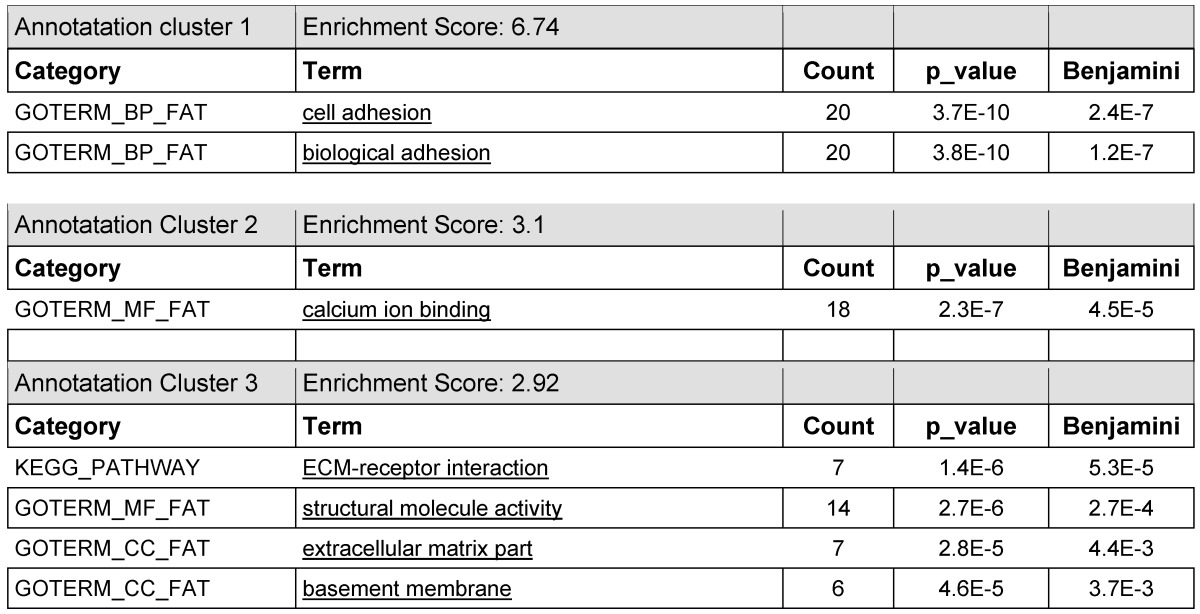

Table 2.

lists the annotation clusters 1-3 with the enrichment scores 6.74; 3.1; and 2.92 of the gene bundle of the most prominent 7 of 100 entries which offer the highest read counts of the KRED-lamin B1 probe 30 min after illumination in DAVID functional annotations analysis which gave clusters of GO term enrichment.

Table 7.

shows the contrasting juxtaposition of the mapping the first 100 genes of the KRED-lamin B1 and histone H2A-KRED bundles. These functional groups offer the highest number of read counts 30 min after illumination and DNA damage.

The determined gene clusters were defined for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp).

Results

The comparison of the affected lamina-located genes versus the genes widely spread over the total chromatin requires a normalization of the measured read counts. Due to the short-lived ROS, especially affected are genes which are located in immediate vicinity to the areas of ROS-formation in the close vicinity of the inner nuclear shell (lamin B1) or the surface of the inner chromatin. We compared the DNA fragmentation by induction of ROS with visible light. This light induces the KillerRed fusion proteins KRED-lamin B1 and histone H2A-KRED to create ROS. The gained sequence data were directly correlated to the ROS-affected genes of the whole inner nuclear chromatin.

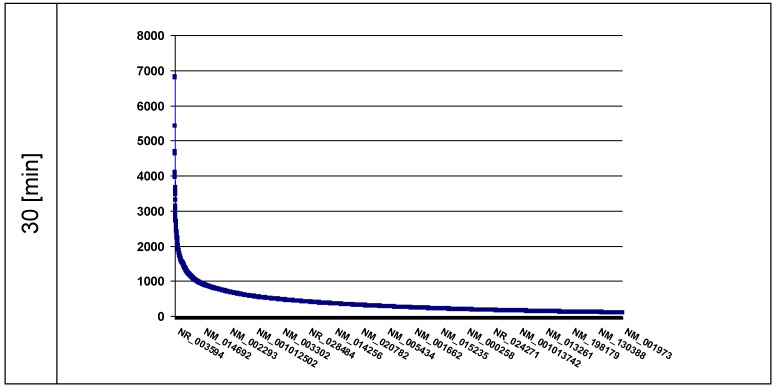

The intention was to find the ds-DNA fragments broken by the induced KRED generated ROS in different loci of the nuclei. The data should give information about the spatial distribution of these DNA pieces. The ROS-affected genes are displayed in the plots in descending order according the amount [read counts] of DNA damages. We tested 30 (Figure 3) and 60 min (shown in Figure 3a, Supplementary Material) after exposition of nuclei to visible light the KRED-lamin B1 induced ds-DNA breaks.

Fig 3.

the plot represents the curves of the read counts (ordinate) 30 min after light exposition; the abscissa lists the affected genes in descending read counts order down to 100. (n = read count). The ordinate shows the number of counts.

After normalization of the read counts of the lamin B1 (30 min) and the histone H2A (30 min) probes, they were compared by divison (read counts-lamin through read counts-histone). A schematical description is given in C: lamin-localized genes (Table 4) and D: whole chromatin -localized genes (Table 5).

Table 4.

lists the first 13 of the 57 most affected genes which show read counts solely in the lamin B1 probe but not in the H2A-KRED control (schematized shown in Table 6, which demonstrates their possible spatial intranuclear localization). The right column describes the physical mapping of the chromosomal regions.

| Refseq ID | Read Counts | Gene Symbol | Description | Physical map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_001127482 | 12550 | SPRYD7 | SPRY domain containing 7 | 13q14.2 [R] |

| NM_001003796 | 6584 | NHP2L1 | non-histone chromosome protein 2-like 1 | 22q13.2 [G] |

| NM_001039210 | 6428 | ALG13 | asparagine-linked glycosylation 13 homolog | Xq23 [G] |

| NM_001004333 | 6331 | RNASEK | RNase kappa | 17p13.1 [R] |

| NM_001035223 | 5688 | RGL3 | Ral guanine nucleotide dissoc stimul-like 3 | 19p13.2 [G] |

| NM_001114106 | 5055 | SLC44A3 | solute carrier family 44, member 3 | 1p21.3 [G] |

| NM_001099410 | 4953 | GPRASP1 | G-protein coupled receptor-assoc sort protein 1 | Xq22.1 [R] |

| NM_001105538 | 4826 | MYBBP1A | myb-binding protein 1A | 17p13.2 [G] |

| NM_001124759 | 4339 | FRG2C | FSHD region gene 2 family, member C | 3p12.3 [G] |

| NM_001099455 | 4305 | CPPED1 | calcineurin-like phosphoesterase dom protein 1 | 16p13.12 [G] |

| NM_001171799 | 3906 | TRIQK | Triple QxxK/R motif-containing protein | 8q22.1 [R] |

| NM_001134364 | 3613 | MAP4 | microtubule-associated protein 4 | 3p21.31 [R] |

| NM_001139518 | 3409 | PRKRA | protein kinase interferon-inducible ds RNA dependent | 2q31.2 [G] |

Table 5.

lists the first 4 of the 25 most affected genes which show read counts in the H2A-KRED control but not in the lamin B1 probe.

| Refseq ID | Read Counts | Gene Symbol | Description | Physical map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_001146197 | 3804 | CCDC168 | coiled-coil domain containing 168 | 13q33.1 [G] |

| NM_001127464 | 3247 | ZNF469 | zinc finger protein 469 | 16q24.2 [G] |

| NM_001042603 | 2974 | KDM5A | lysine (K)-specific demethylase 5A | 12p13.33 [R] |

| NM_001110781 | 2580 | SLC35E2B | solute carrier family 35, member E2B | 1p36.33 [R] |

A. KRED-Lamin B1 fusion protein - genes in the immediate vicinity of the Lamina

We identified 24,502 affected genes (offering read counts between 6,824-1) in the 30 min probe and 24,300 genes (offering read counts between 6,039-1) in the 60 min probe (Figure 3a, Supplementary Material). To analyze these hits, we focused on the RefSeq IDs with the highest number of read counts of DNA damages in the four most affected genes after 30 min: the NR_003594, which corresponds to REXO1L2P, featured 6,824 counts, closely followed by the NM_003482 (6,806 counts) and NM_005560 (5,420 counts). The independently prepared 60 min probe showed the same order of highest affected genes but with a little lower read counts (6,039), and the IDs NM_003482 (4,973 counts) and NM_005560 (5,420 counts) (as shown exemplarily in Supplementary Material: Table 1a); (further affected genes are listed in detail in Supplementary Material: Table 1a).

The graph (Figure 3) gives insight into the extent of genetic breakpoints caused by ROS versus the affected genes. The different annotation clusters generated by DAVID software are listed in the following tables and contain the affected genes arbitrarily bundled in amounts of 100. Table 2 lists the prominent 7 genes of the first 100 entries in this functional annotations analysis which gave clusters of GO term enrichment. Further 600 genes, combined to bundles of 100 genes, are listed in the Supplementary Material (Table 3a - 7a).

We also determined the spatial localization of genes close to the nuclear lamina (radius 0.1 µm): The first hint is given by the ROS damaged genes following descending read counts. (The corresponding ONIM IDs are listed in Table 1a, right column (Supplementary Material).

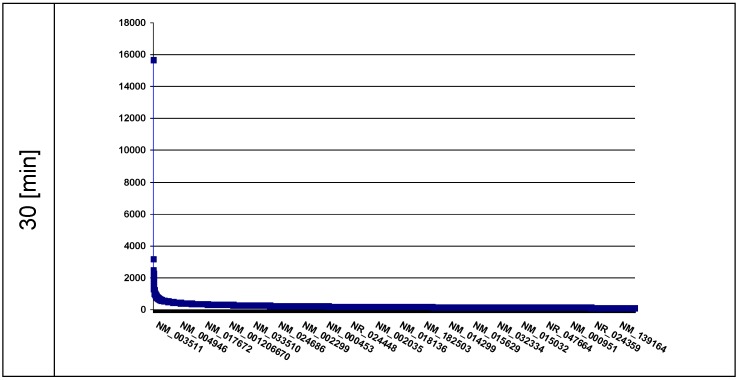

B. Histone H2A-KRED - (gene localization distributed over the whole nucleus)

As a control we identified the ROS-affected genes distributed across the nuclear chromatin using the recombinant fusion protein histone H2A-KRED whose histone part is an essential element of the whole chromatin structure. The ROS affected genes are displayed in plots according to the extent [read counts] in a descending order of DNA damages (Figure 4).

Fig 4.

The plot represents the curve of the read counts (ordinate) 30 min after light exposition of the histone H2A-KRED containing nuclei; the axis of abscissa lists the affected genes in descending read counts order. (■ = read count)

Our second probe, the histone H2A-KRED should be distributed over the whole nuclear chromatin in a 3-dimensional way.

We identified 25,870 affected genes (offering read counts between 15,664-1) in the 30 min probe (Figure 4). It is particularly noticeable that the RefSeq Id NM_003511 exhibits by far the highest lot of read counts of DNA damages in the affected genes after 30 min. Behind this histone H2A type 1 (HIST1H2AL) gene followed the MTRNR2L2 encoding the humanin-like protein 2 in a clear numeric distance with 3,185 read counts, and with 2,491 read counts the RefSeq ID NR_003594 which corresponds to REXO1L2P. This is closely followed by the RefSeq IDs NR_002728 corresponding to the KCNQ1OT1 gene (2,450 read counts) and the NM_001190702 (2,414 read counts) encoding the humanin-like protein 8. Here it should be mentioned that REXO1L2P was aleady identified in the lamin B1 probe.

The RefSeq ID NM_003482 (2,266 read counts) corresponds to the histone-lysine N-methyltransferase gene encoding the MLL2 protein.

C. Lamin B1- but not chromatin-localized ROS-affected genes

After normalization of the data we compared the affected genes of the lamin B1 probe with the histone H2A probe. The search clearly shows read counts in the lamin B1-KRED probes not present in the histone H2A-KRED control. 1,065 ROS-affected genes were detected and after data normalization the genes with the highest amount of read counts are listed in a descending order (12,550-3,409 read counts) in Table 4 and (1,003 read counts) are shown exemplarily in Table 13a, with 57 genes (Supplementary Material).

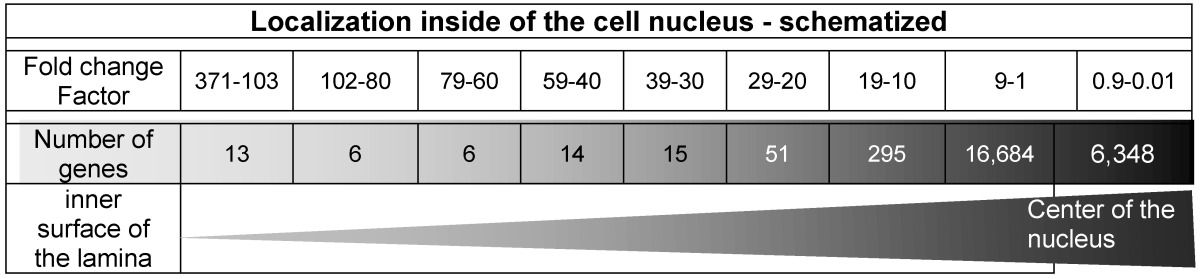

The spatial localization of these 13 genes which offer the highest read counts in the nuclei is displayed in Table 6 and characterized with the fold change factor range between 371 and 103.

Table 6.

illustrates the graphical determination of the damage density and lists the ROS-affected genes according to the read counts' fold change factors in descending order. It represents the radial distribution of the territorial range starting from the inner surface of the nucleus inwardly to the middle of the nucleus. The triangle (lower line) symbolizes the increasing number of damaged genes from the inner surface (lamina) to the center of the nucleus.

D. Chromatin-localized - but not lamin B1 localized ROS-affected genes

We next compared the normalized data of lamin B1 with the histone H2A probes listed in Table 5 showing the most affected genes of the histone H2A probe.

The comparison of the lamin B1 probe against the H2A probe shows read counts in the spatial H2A-control but not in the lamin B1 probes. 2,432 ROS-affected genes were detected and after data normalization the genes with the highest values (3,804-2,580) are listed in descending order (shown in Table 5) and to 1,003 read counts are shown in Table 14a (Supplementary Material):

E. Fold change: read counts ratio between territorial lamin B1 - and nuclear chromatin H2A-localized genes

These fold change data provide first information concerning the inner nuclear localization with the utmost probability. The factors may provide recommendations for a possible inner nuclear localization and for a reasonably stepwise classification of the ROS-affected genes. The fold change is a quotient formed between the read counts of the lamin B1 probe and the H2A-KRED probe.

Table 6 displays 13 genes featuring a ratio range between the factors 371 and 103 which indicate a clear localization very close to the lamin B1. In contrast, in the middle of the nucleus, 6,348 genes are listed between the fold change factors 0.9 and 0.01 generated by histone H2A-KRED.

The comparison of these fold change factors, as listed in Table 6, shows, that the ranges between 3.7 × 102 and 101 list only 400 genes, whereas the relatively small range of the factors between 101 - 10-1 lists 23,032 genes.

F. Gene analysis

DAVID bioinformatics resources allow insight in biological and pharmacological mechanisms and account for a better understanding of the association of DNA damages with genetic diseases 55, 56. The direct links to the corresponding GO IDs are given from data which are listed in the tables of Supplementary Material.

Additionally, we used the BlastiX program (NCBI Blast2GO, Version 2.6.2), for the appraisal of the FASTA sequences generated by HUSAR software of the listed “100-gene” bundles (see Supplementary Material: Table 3a - Table 7a) with the highest read counts and a Blast Expect Value with the cut off 1.0E-3 of the 600 of most ROS-damaged genes.

Both bundles, the KRED-lamin B1 (Table 2) and the histone H2A-KRED probes (Table 11a Supplementary Material) harbour annotation clusters with the highest enrichment scores and Benjamini values. The Table 7 generates graphics itemized according to the GO annotations of molecular, function, biological process and cellular components.

With these data we generated a graphical determination of the heaviest light damaged functional gene groups of the histone H2A-KRED and KRED-lamin B1 probes (Table 7)

As described in the methods section we used the Blast2GO tool for functional annotation of the FASTA nucleotide sequences. The software BLAST identifies homologous sequences, MAPPING retrieves GO terms, ANNOTATION performs reliable GO functions and enrichment scores and ANALYSIS produces graphical display of annotation data with GO graphs. The comparison data are shown in Table 7.

G. Gene alterations - highest read count number

The NCBI OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) database shows the gene mapping with close connection to human genes and their genetic phenotypes. This helps to understand the relationship between altered genotypes and the resulting clinical entities such as genetic disorders.

Resulting from our Table 1 and Table 1a (Supplementary Material), the four genes with the highest damage read count numbers and the resulting laminopatic diseases are characterized shortly.

Table 1.

lists the ROS affected genes offering the highest damage read count numbers. It is a description of the four genes of the KRED-lamin B1 probe with the highest read counts (details shown in Supplementary Material: Table 1a, right column).

| RefseqID | Read Counts | Gene Symbol | Description | Physical map | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 60 min | ||||

| NR_003594 | 6,824 | 6,039 | REXO1L2P | RNA exonuclease 1 homologue-like 2 | 19p13.3 [R] |

| NM_003482 | 6,806 | 4,973 | MLL2 | histone-lysine N-methyltransferase MLL2 | 12q13.12 [G] |

| NM_005560 | 5,420 | 3,793 | LAMA5 | laminin subunit alpha-5 precursor | 20q13.33 [R] |

| NM_001164462 | 4,688 | 4,544 | MUC12 | mucin-12 precursor | 7q22.1 [R] |

RNA exonuclease 1 homologue-like 2 pseudogene- REXO1L2P (OMIM ID 609614)

In the lamin B1 as well as in the histone probes we detected highest damage rates of the REXO1L2P. The gene, mapped at the R-band of the chromosome 19p13.3, codes for the RNA 3' exonuclease 1 REX1. HomoloGene data (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene/) indicate that this gene is present in the common ancestor of eukaryotes offering orthology from human down to Saccharomyces cerevisia. It is documented as a human pseudogene homologue to the yeast RNase gene D family whose gene products are involved in maturation processes of 5.8S rRNA 57, 58. Additionally, animal studies demonstrated that the disruption of REX1 influences differentiation and cell cycle regulation of embryonic stem cells 59.

Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase MLL2 - MLL2 (OMIM ID 602113)

The MLL2 mapped to the 12q13.12 region (G-band) and is involved in mutations, translocations and duplications between disease genes whose alteration of function is strongly associated with cancer 60. Diseases of blood forming organs were documented like acute leukemia (ALL) 61 and in lymphomagenesis like non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) 62.

Laminin subunit alpha-5 precursor LAMA5 (OMIM ID 601033)

The LAMA5 mapped at the R-band of 20q13.33 and its expression is tissue-specific, mainly in brain, placenta, kidneys, lung and skeletal muscles 63. Laminins are large glycoproteins found in basement membranes where they play a vital role in tissue architecture and cell behaviour. LAMA5 polymorphisms are associated with anthropometric traits, fasting lipid profile, polycystic kidney disease (PKD) and altered plasma glucose levels 64. Furthermore, the association of the Lama5 protein in organogenesis and placental function during pregnancy is documented 64-66.

Mucin-12 precursor MUC12 (OMIM ID 604609)

The cytogenic location of MUC12 is the R-band of chromosome 7q22.1. It was isolated first by the Williams group in 1999. MUC12 is a member of mucin genes coding for epithelial mucins, large cell surface glycoproteins, involved in cell protection and signalling. Down regulation or loss of function is identified in colorectal cancer (CRC) 67. The lower expression status is considered as a meaningful independent prognostic factor in states II and III of CRC 68.

Discussion

Collecting evidences for the hypothesis of the evolutionary origin of the nucleus and its compartmentalized architecture is a great challenge in the post-genomic era 69. Chromatin studies demonstrated radial chromosomal arrangements inside of ellipsoid and spherical human cell nuclei 70. With the knowledge about the spatial arrangement of the intranuclear chromosomal territories it becomes evident, that chromosomes harbouring tight gene clusters are preferably localized in the center. Chromosomes with less genomic clusters are localized more peripherally adjacent to the nuclear lamina and furthermore, the larger chromosomes are positioned even more peripherally 71. FISH studies of such chromosomes substantiated this chromatin arrangement, demonstrating the preferred nuclear interior localization of gene-rich chromosomes, while the gene-poor chromosomes are accumulated closer to the nuclear lamina 72, 73. An also well documented feature of the eukaryotic nuclear organization is the observed genome segregation into the transcriptionally active euchromatin and the transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin 74, 75.

Amongst others a further aspect is the cytogenetic classification in R- and G-bands, which might allow more insight into the complex structural chromosomal architecture. The ISCN (International System for Cytogenetic Nomenclature) introduced an ideogram in 1971, which comprehended a diagrammatic representation of banding patterns. With the help of this band morphology of each chromosome and a unique numbering system chromosomal specific bands and regions could be described 76. These coloured chromosomal regions (banding) were named G-bands, (G for Giemsa) and not coloured R-bands, (R for Revers) 77, 78.

This staining behaviour is not well understood, but this banding allows a clear identification of the human chromosomes. The R-bands mainly consist of GC-bases and are gene rich, especially including housekeeping genes, in contrast, the G-bands have a higher AT content and are mainly occupied by tissue-specific genes 79. Also CpG islands are specific to R-band exons 80 and often associated with Alu-sequences, which transcribe non coding RNA with RNA-Polymerase III 81.

The detected KCNQ1OT1 gene e.g. maps at 11p15.5 (Table 3) and is located inside of a chromosomal R-band and could be considered as an example for a non-protein coding gene whose transcribed RNA is critical in the chromatin conformation 82-84. This was substantiated with recent data of gene expression comparison studies of differently structured genes and methylation patterns pivotal in gene regulation showing a high conservation between human and bovine 85.

Table 3.

lists the 30 min probe of the ROS affected genes offering the highest read count number in the histone H2A with fragmented DNA.

| Refseq ID | Read Counts | Gene Symbol | Description | Physical map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_003511 | 15,664 | HIST1H2AL | histone H2A type1 | 6p22.1 [G] |

| NM_001190470 | 3,185 | MTRNR2L2 | humanin-like protein 2 | 5q14.1 [G] |

| NR_003594 | 2,491 | REXO1L2P | RNA exonuclease 1 hom.-like 2 (pseudo) | 19.13.3 [R] |

| NR_002728 | 2,450 | KCNQ1OT1 | antisense transcript 1 (non-protein coding) | 11p15.5 [R] |

Genes of the R banding are replicated early in contrast to the genes in G-bands 5, 80, 86, 87.

In case of the replication of chromosomes, the S-phase does not proceed evenly, but at different time points in certain chromosomal areas. Both, the early and the late replication events are properties which are constant and inherited for all chromosomal segments and are considered as a characteristic of a certain cell type. It is important to note O'Keefe's detections: the areas replicating early are preferably arranged in the center of the nucleus. The late replicated chromosomal areas are located predominantly close to the inner surface of the nuclear envelope 88-90.

Adjacent to the lamin A-types, the B-types represent major intermediate filaments of the nucleus and are involved in manifold interactions between the inner nuclear membrane and the the nuclear chromatin 33, 91. The lamin proteins-based skeleton structure for formation of adaptor functions is important in chromatin organization and in modulation of signal transduction pathways. Minimal alterations in the chromatin structure can manifest clinical appearances 92, 93. The extremely high organized chromatin architecture is pivotal in the strongly controlled gene expression. Dysregulations base on changes of the nuclear dis-organization and a disrupted nuclear structure is often noted in genetic diseases like cancer 94-96. Studies of nuclear structure and activity using biophysical, chemical, and nanoscience methodologies under the aspect of problems, deriving from mutations and chromosome exchanges, in the genome organization demonstrate a sensitive connection to gene localization and activity 97-99.

Various groups indicated a non-random but highly organized structure of the genes as shown in Nicolini's, Harper's, Zink's and Cremers' research work 5, 11, 100-103.

Based on these above mentioned research results, we investigated which DNA sequences and genes in the nuclei were affected by light induced ROS. We constructed plasmids producing the KRED-lamin B1 fusion protein which is then located close to the nuclear inner surface (Supplementary Material: Figure 1a) and compared the damaged DNA sequences, with structures damaged by the activated recombinant H2A-KRED protein spatially scattered across the whole chromatin (Supplementary Material: Figure 1b).

The fact that ROS is capable to damage and finally kill cells is uncontradicted. These genotoxic and oxidative stress parameters damage DNA with double-strand breaks (DSBs), which then lead to an induction of DNA damage response (DDR).

In contrast to the lamin B1 induced break points, which can be interpreted to be very close to the nuclear shell, the histone H2A data cannot delineate gene positions and is our control.

We characterized especially genes with the highest damage rates induced by ROS, but not detected by histone H2A-KRED (Table 4 and Table 6 and Table 13a, Supplementary Material).

The strong increase of DNA damages from the lamina to the center of the nucleus supports the gradient of gene and chromosomes density in this direction.

Using independent triplicates of KRED-lamin B1 probes we detected the following damaged genes REXO1L2P, MLL2, LAMA5, and MUC12 with the nearly identical read count number (30 / 60 [min]) 6,824/6,039; 6,806/4,973; 5,420/3,793 and 4,688/4,544 respectively (Table 1). Chromatin dynamics and remodeling are required for the rapid DSB repair by mechanisms, highly conserved from yeast to humans as documented well from Price and Osley 104-106 .

Generally, the toxic potential of ROS depends on the distance from the point of its origin and is considered as assured. Here the differences in the parameters like absorption coefficients, spectral inhomogeneity of the incident light or in different ROS building capacities are not subject of our investigations.

Our data sets and especially the detected “fold change” data (Table 6) show a clear increase of the events of gene damage and indicate an enhancement of the density of the genes from the lamina inwards to the center of the nucleus as shown in Table 6.

The first 13 genes (listed in Table 4) offer the highest fold change factors between 371 and 103 in the lamin B1 probe but they are not measurable in the histone control. This suggests a localization near the lamin B1 protein at the inner surface of the nuclear envelope.

These results of the ROS cytotoxic effects, caused by both fusion proteins, the KRED-Lamin B1 variant as well as the histone H2A-KRED 51, demand further investigations of the local DNA characterization, chromosomal architecture and genotyping.

DNA of genes located at the nuclear periphery is generally a direct object for the insertion of viral DNA genomes and may promote formation of transcriptional activator complexes on the viral and cellular genome. The Silva (HPV) and the Marcello (HIV) groups demonstrated impressively, that the nuclear periphery also has sites for activation of transcription which highlights the importance of the nuclear lamina and the closely located genes in transcriptional activation and repression 107, 108.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables and figures

Acknowledgments

We thank the genomics and proteomics core facility group for support and Harald Hermann for the provided lamin B1 sequence.

On behalf of his retirement we like to thank Prof. Wolfhard Semmler for his enthusiasm, his inspiration, and his financial support for our work.

References

- 1.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B. et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW. et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadoni N, Langer S, Fauth C. et al. Nuclear organization of mammalian genomes. Polar chromosome territories build up functionally distinct higher order compartments. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:1211–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridger JM, Boyle S, Kill IR. et al. Re-modelling of nuclear architecture in quiescent and senescent human fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 2000;10:149–52. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cremer T, Kreth G, Koester H. et al. Chromosome territories, interchromatin domain compartment, and nuclear matrix: an integrated view of the functional nuclear architecture. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2000;10:179–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zink D, Sadoni N, Stelzer E. Visualizing chromatin and chromosomes in living cells. Methods. 2003;29:42–50. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabl C. Über Zelltheilung. Morphologisches Jahrbuch Band 10, zweites Heft. 1885: 214-330.

- 8.Boveri T. Die Blastomerenkerne von Ascaris megalocephala und die Theorie der Chromosomenindividualität. Archiv für Zellforschung. 1909;3:181–268. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cremer T, Cremer C. Rise, fall and resurrection of chromosome territories: a historical perspective. Part I. The rise of chromosome territories. Eur J Histochem. 2006;50:161–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cremer T, Cremer C. Rise, fall and resurrection of chromosome territories: a historical perspective. Part II. Fall and resurrection of chromosome territories during the 1950s to 1980s. Part III. Chromosome territories and the functional nuclear architecture: experiments and models from the 1990s to the present. Eur J Histochem. 2006;50:223–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cremer C, Munkel C, Granzow M. et al. Nuclear architecture and the induction of chromosomal aberrations. Mutat Res. 1996;366:97–116. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1110(96)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rouquette J, Cremer C, Cremer T. et al. Functional nuclear architecture studied by microscopy: present and future. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2010;282:1–90. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)82001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koonin EV. Evolution of genome architecture. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muck J, Zink D. Nuclear organization and dynamics of DNA replication in eukaryotes. Front Biosci. 2009;14:5361–71. doi: 10.2741/3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuleger N, Robson MI, Schirmer EC. The nuclear envelope as a chromatin organizer. Nucleus. 2011;2:339–49. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.5.17846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun HB, Shen J, Yokota H. Size-dependent positioning of human chromosomes in interphase nuclei. Biophys J. 2000;79:184–90. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76282-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bussiek M, Muller G, Waldeck W. et al. Organisation of nucleosomal arrays reconstituted with repetitive African green monkey alpha-satellite DNA as analysed by atomic force microscopy. Eur Biophys J. 2007;37:81–93. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0166-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammermann M, Toth K, Rodemer C. et al. Salt-dependent compaction of di- and trinucleosomes studied by small-angle neutron scattering. Biophys J. 2000;79:584–94. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76318-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weidemann T, Wachsmuth M, Knoch TA. et al. Counting nucleosomes in living cells with a combination of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and confocal imaging. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olins AL, Olins DE, Zentgraf H. et al. Visualization of nucleosomes in thin sections by stereo electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1980;87:833–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.87.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan SN, Khan AU. Role of histone acetylation in cell physiology and diseases: An update. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1401–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calestagne-Morelli A, Ausio J. Long-range histone acetylation: biological significance, structural implications, and mechanisms. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84:518–27. doi: 10.1139/o06-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregory PD, Wagner K, Horz W. Histone acetylation and chromatin remodeling. Exp Cell Res. 2001;265:195–202. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craig JM, Bickmore WA. Chromosome bands--flavours to savour. Bioessays. 1993;15:349–54. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheuermann MO, Tajbakhsh J, Kurz A. et al. Topology of genes and nontranscribed sequences in human interphase nuclei. Exp Cell Res. 2004;301:266–79. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santoni N. Thesis: Untersuchungen zur Organisation der Transkription und DNA-Replikation im Kontext der Chromatinarchitektur im Kern von Säugerzellen. München, Ludwigs-Maximilians-Universität. 2003. pp. 1–109.

- 27.Skalnikova M, Kozubek S, Lukasova E. et al. Spatial arrangement of genes, centromeres and chromosomes in human blood cell nuclei and its changes during the cell cycle, differentiation and after irradiation. Chromosome Res. 2000;8:487–99. doi: 10.1023/a:1009267605580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartova E, Kozubek S, Kozubek M. et al. The influence of the cell cycle, differentiation and irradiation on the nuclear location of the abl, bcr and c-myc genes in human leukemic cells. Leuk Res. 2000;24:233–41. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(99)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zehner ZE. Regulation of intermediate filament gene expression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1991;3:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(91)90167-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Worman HJ, Evans CD, Blobel G. The lamin B receptor of the nuclear envelope inner membrane: a polytopic protein with eight potential transmembrane domains. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1535–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmer L, Worman HJ. Inner nuclear membrane proteins: functions and targeting. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1741–7. doi: 10.1007/PL00000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostlund C, Worman HJ. Nuclear envelope proteins and neuromuscular diseases. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27:393–406. doi: 10.1002/mus.10302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg M, Harel A, Gruenbaum Y. The nuclear lamina: molecular organization and interaction with chromatin. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1999;9:285–93. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v9.i3-4.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD. et al. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:21–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maraldi NM, Lattanzi G, Sabatelli P. et al. Immunocytochemistry of nuclear domains and Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy pathophysiology. Eur J Histochem. 2003;47:3–16. doi: 10.4081/802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dahl KN, Scaffidi P, Islam MF. et al. Distinct structural and mechanical properties of the nuclear lamina in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10271–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601058103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vlcek S, Foisner R. A-type lamin networks in light of laminopathic diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:661–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenbaum L, Rothmann C, Lavie R. et al. Green fluorescent protein photobleaching: a model for protein damage by endogenous and exogenous singlet oxygen. Biol Chem. 2000;381:1251–8. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holz M, Heil SR, Sacco A. Temperature-dependent self-diffusion coefficients of water and six selected molecular liquids for calibration in accurate H-1 NMR PFG measurements. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2000;2:4740–2. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Einstein A. Fürth R, Cowper AD, editors. New York: Dover Publications, Inc; 1956. Investigations of the Theory of Brownian Movement; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 41.41. von Smoluchowski M. Theorie der Brownschen Molekularbewegung. Ann Phys. 1906;21:756–80. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magde D, Elson E, Webb W. Thermodynamic Fluctuations in a Reacting System-Measurement by Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. Physical Review Letters. 1972;29:705–8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michalet X. Mean square displacement analysis of single-particle trajectories with localization error: Brownian motion in an isotropic medium. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2010;82:041914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.041914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foote CS. Definition of type I and type II photosensitized oxidation. Photochem Photobiol. 1991;54:659. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1991.tb02071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sies H. Strategies of antioxidant defense. Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:213–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bulina ME, Chudakov DM, Britanova OV. et al. A genetically encoded photosensitizer. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:95–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stone KR, Mickey DD, Wunderli H. et al. Isolation of a human prostate carcinoma cell line (DU 145) Int J Cancer. 1978;21:274–81. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910210305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waldeck W, Mueller G, Wiessler M. et al. Autofluorescent proteins as photosensitizer in eukaryontes. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6:365–73. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bulina ME, Lukyanov KA, Britanova OV. et al. Chromophore-assisted light inactivation (CALI) using the phototoxic fluorescent protein KillerRed. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:947–53. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waldeck W, Heidenreich E, Mueller G. et al. ROS-mediated killing efficiency with visible light of bacteria carrying different red fluorochrome proteins. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2012;109:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waldeck W, Mueller G, Wiessler M. et al. Positioning Effects of KillerRed inside of Cells correlate with DNA Strand Breaks after Activation with Visible Light. Int J Med Sci. 2011;8:97–105. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Senger M, Glatting KH, Ritter O. et al. X-HUSAR, an X-based graphical interface for the analysis of genomic sequences. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1995;46:131–41. doi: 10.1016/0169-2607(94)01610-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donawho CK, Luo Y, Luo Y. et al. ABT-888, an orally active poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor that potentiates DNA-damaging agents in preclinical tumor models. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2728–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerthsen C, Kneser H, Vogel H. Strahlungsenergie. In. Physik. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. 1977.

- 55.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Tan Q. et al. The DAVID Gene Functional Classification Tool: a novel biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large gene lists. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R183. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Hoof A, Lennertz P, Parker R. Three conserved members of the RNase D family have unique and overlapping functions in the processing of 5S, 5.8S, U4, U5, RNase MRP and RNase P RNAs in yeast. EMBO J. 2000;19:1357–65. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tamura K, Miyata K, Sugahara K. et al. Identification of EloA-BP1, a novel Elongin A binding protein with an exonuclease homology domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:189–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scotland KB, Chen S, Sylvester R. et al. Analysis of Rex1 (zfp42) function in embryonic stem cell differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1863–77. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prasad R, Zhadanov AB, Sedkov Y. et al. Structure and expression pattern of human ALR, a novel gene with strong homology to ALL-1 involved in acute leukemia and to Drosophila trithorax. Oncogene. 1997;15:549–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karlin S, Chen C, Gentles AJ. et al. Associations between human disease genes and overlapping gene groups and multiple amino acid runs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17008–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262658799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ. et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. 2011;476:298–303. doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Durkin ME, Loechel F, Mattei MG. et al. Tissue-specific expression of the human laminin alpha5-chain, and mapping of the gene to human chromosome 20q13.2-13.3 and to distal mouse chromosome 2 near the locus for the ragged (Ra) mutation. FEBS Lett. 1997;411:296–300. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00686-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Luca M, Chandler-Laney PC, Wiener H, Common variants in the LAMA5 gene associate with fasting plasma glucose and serum triglyceride levels in a cohort of pre-and early pubertal children. J Pediatr Genet. 2012. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.De Luca M, Crocco P, Wiener H. et al. Association of a common LAMA5 variant with anthropometric and metabolic traits in an Italian cohort of healthy elderly subjects. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:60–4. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goldberg S, Adair-Kirk TL, Senior RM. et al. Maintenance of glomerular filtration barrier integrity requires laminin alpha5. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:579–86. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009091004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams SJ, McGuckin MA, Gotley DC. et al. Two novel mucin genes down-regulated in colorectal cancer identified by differential display. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4083–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matsuyama T, Ishikawa T, Mogushi K. et al. MUC12 mRNA expression is an independent marker of prognosis in stage II and stage III colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2292–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Postberg J, Lipps HJ, Cremer T. Evolutionary origin of the cell nucleus and its functional architecture. Essays Biochem. 2010;48:1–24. doi: 10.1042/bse0480001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cremer M, von HJ, Volm T. et al. Non-random radial higher-order chromatin arrangements in nuclei of diploid human cells. Chromosome Res. 2001;9:541–67. doi: 10.1023/a:1012495201697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cremer T, Cremer C. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:292–301. doi: 10.1038/35066075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Simonis M, de LW. FISH-eyed and genome-wide views on the spatial organisation of gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:2052–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Markaki Y, Smeets D, Fiedler S. et al. The potential of 3D-FISH and super-resolution structured illumination microscopy for studies of 3D nuclear architecture: 3D structured illumination microscopy of defined chromosomal structures visualized by 3D (immuno)-FISH opens new perspectives for studies of nuclear architecture. Bioessays. 2012;34:412–26. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DuBois KN, Alsford S, Holden JM. et al. NUP-1 Is a large coiled-coil nucleoskeletal protein in trypanosomes with lamin-like functions. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Soderberg E, Hessle V, von EA. et al. Profilin is associated with transcriptionally active genes. Nucleus. 2012;3:290–9. doi: 10.4161/nucl.20327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Report of the Paris Conference (1971) Standardization in Human Cytogenetics.Birth Defects. Original Article Series, The National Foundation, New York. 1971. [PubMed]

- 77.Heim S. Genetic nomenclature: ISCN and ISGN. Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 1996;13:R3. doi: 10.3109/08880019609030800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kosyakova N, Weise A, Mrasek K, The hierarchically organized splitting of chromosomal bands for all human chromosomes. Molecular Cytogenetics. 2009. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Houck CM, Rinehart FP, Schmid CW. A ubiquitous family of repeated DNA sequences in the human genome. J Mol Biol. 1979;132:289–306. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Craig JM, Bickmore WA. The Distribution of Cpg Islands in Mammalian Chromosomes. Nature Genetics. 1994;7:376–82. doi: 10.1038/ng0794-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mariner PD, Walters RD, Espinoza CA. et al. Human Alu RNA is a modular transacting repressor of mRNA transcription during heat shock. Mol Cell. 2008;29:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Korostowski L, Sedlak N, Engel N. The Kcnq1ot1 Long Non-Coding RNA Affects Chromatin Conformation and Expression of Kcnq1, but Does Not Regulate Its Imprinting in the Developing Heart. Plos Genetics. 2012. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Peng HH, Chang SD, Chao AS. et al. DNA methylation patterns of imprinting centers for H19, SNRPN, and KCNQ1OT1 in single-cell clones of human amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cell. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;51:342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kanduri C. Kcnq1ot1: A chromatin regulatory RNA. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2011;22:343–50. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Robbins KM, Chen ZY, Wells KD, Expression of Kcnq1Ot1, Cdkn1C, H19, and Plagl1 and the Methylation Patterns at the Kvdmr1 and H19/Igf2 Imprinting Control Regions Is Conserved Between Human and Bovine. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2012. 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Craig JM, Bickmore WA. The Distribution of Cpg Islands in Mammalian Chromosomes (Vol 7, Pg 376, 1994) Nature Genetics. 1994;7:551. doi: 10.1038/ng0794-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Drouin R, Lemieux N, Richer CL. Analysis of Dna-Replication During S-Phase by Means of Dynamic Chromosome-Banding at High-Resolution. Chromosoma. 1990;99:273–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01731703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.O'Keefe RT, Henderson SC, Spector DL. Dynamic organization of DNA replication in mammalian cell nuclei: spatially and temporally defined replication of chromosome-specific alpha-satellite DNA sequences. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1095–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.5.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zink D, Bornfleth H, Visser A. et al. Organization of early and late replicating DNA in human chromosome territories. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:176–88. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Van der Aa N, Cheng J, Mateiu L. et al. Genome-wide copy number profiling of single cells in S-phase reveals DNA-replication domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wilson KL, Foisner R. Lamin-binding Proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000554. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Filesi I, Gullotta F, Lattanzi G. et al. Alterations of nuclear envelope and chromatin organization in mandibuloacral dysplasia, a rare form of laminopathy. Physiol Genomics. 2005;23:150–8. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00060.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brickner JH. Nuclear architecture: the cell biology of a laminopathy. Curr Biol. 2011;21:R807–R809. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reddy KL, Feinberg AP. Higher order chromatin organization in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Martins RP, Finan JD, Guilak F. et al. Mechanical regulation of nuclear structure and function. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2012;14:431–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071910-124638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gadji M, Vallente R, Klewes L. et al. Nuclear remodeling as a mechanism for genomic instability in cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2011;112:77–126. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387688-1.00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.O'Brien TP, Bult CJ, Cremer C. et al. Genome function and nuclear architecture: from gene expression to nanoscience. Genome Res. 2003;13:1029–41. doi: 10.1101/gr.946403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kreth G, Munkel C, Langowski J. et al. Chromatin structure and chromosome aberrations: modeling of damage induced by isotropic and localized irradiation. Mutat Res. 1998;404:77–88. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ihalainen TO, Niskanen EA, Jylhava J. et al. Parvovirus induced alterations in nuclear architecture and dynamics. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nicolini C. Nuclear structure and higher order gene structure: their role in the control of chemically-induced neoplastic transformation. Toxicol Pathol. 1984;12:149–54. doi: 10.1177/019262338401200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kreth G, Finsterle J, Cremer C. Virtual radiation biophysics: implications of nuclear structure. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;104:157–61. doi: 10.1159/000077481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nalepa G, Harper JW. Visualization of a highly organized intranuclear network of filaments in living mammalian cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;59:94–108. doi: 10.1002/cm.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fedorova E, Zink D. Nuclear genome organization: common themes and individual patterns. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xu Y, Price BD. Chromatin dynamics and the repair of DNA double strand breaks. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:261–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.2.14543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xu Y, Ayrapetov MK, Xu C. et al. Histone H2A.Z Controls a Critical Chromatin Remodeling Step Required for DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. Mol Cell. 2012;48:723–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tsukuda T, Fleming AB, Nickoloff JA. et al. Chromatin remodelling at a DNA double-strand break site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2005;438:379–83. doi: 10.1038/nature04148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Silva L, Oh HS, Chang L, Roles of the nuclear lamina in stable nuclear association and assembly of a herpesviral transactivator complex on viral immediate-early genes. MBio. 2012. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Dieudonne M, Maiuri P, Biancotto C. et al. Transcriptional competence of the integrated HIV-1 provirus at the nuclear periphery. EMBO J. 2009;28:2231–43. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables and figures