Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate changes in body composition after 12 months of high-intensity progressive resistance training (PRT) in relation to changes in insulin resistance (IR) or glucose homeostasis in older adults with type 2 diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

One-hundred three participants were randomized to receive either PRT or sham exercise 3 days per week for 12 months. Homeostasis model assessment 2 of insulin resistance (HOMA2-IR) and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were used as indices of IR and glucose homeostasis. Skeletal muscle mass (SkMM) and total fat mass were assessed using bioelectrical impedance. Visceral adipose tissue, mid-thigh cross-sectional area, and mid-thigh muscle attenuation were quantified using computed tomography.

RESULTS

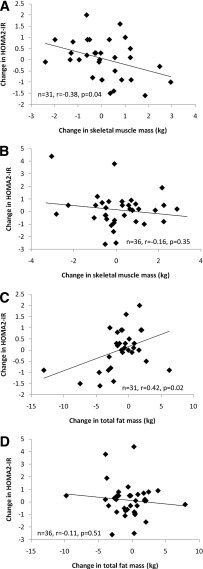

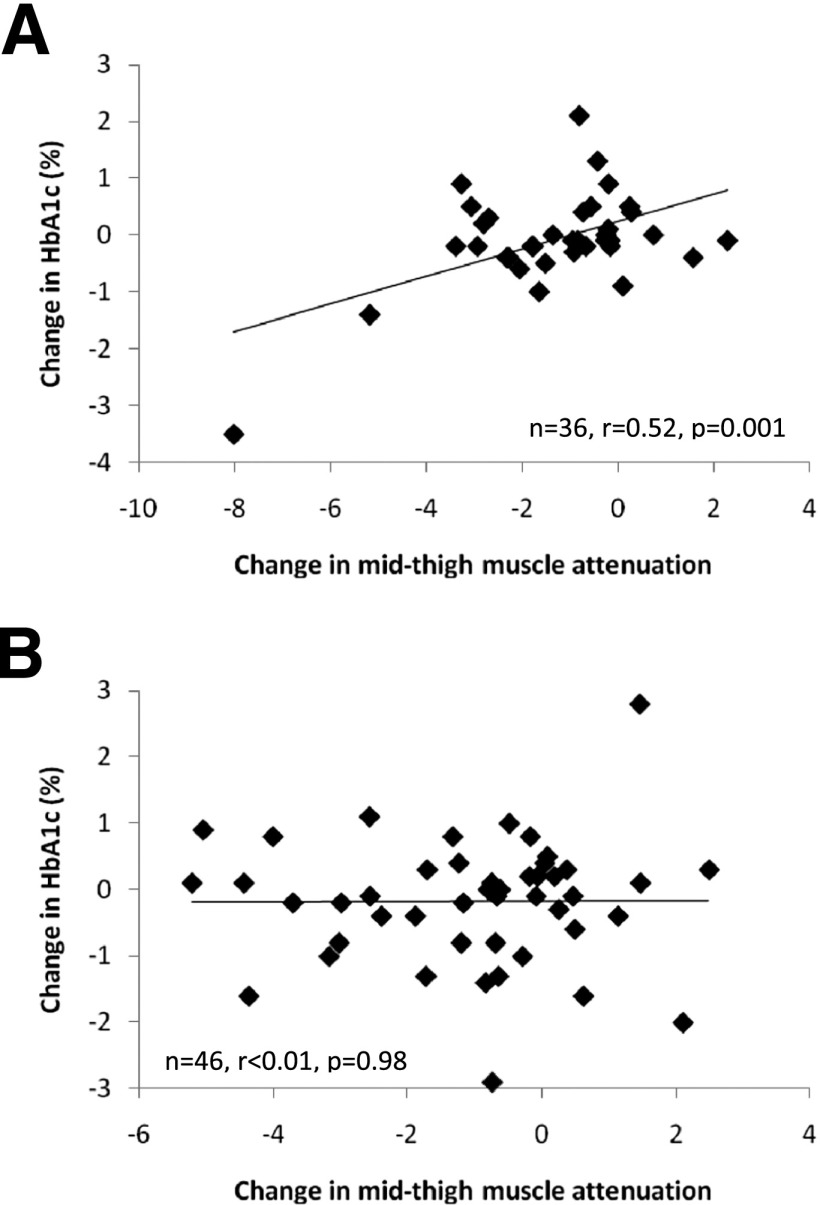

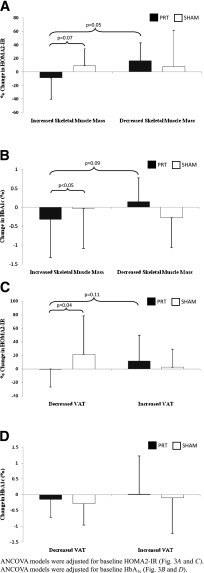

Within the PRT group, changes in HOMA2-IR were associated with changes in SkMM (r = −0.38; P = 0.04) and fat mass (r = 0.42; P = 0.02). Changes in visceral adipose tissue tended to be related to changes in HOMA2-IR (r = 0.35; P = 0.07). Changes in HbA1c were related to changes in mid-thigh muscle attenuation (r = 0.52; P = 0.001). None of these relationships were present in the sham group (P > 0.05). Using ANCOVA models, participants in the PRT group who had increased SkMM had decreased HOMA2-IR (P = 0.05) and HbA1c (P = 0.09) compared with those in the PRT group who lost SkMM. Increases in SkMM in the PRT group decreased HOMA2-IR (P = 0.07) and HbA1c (P < 0.05) compared with those who had increased SkMM in the sham group.

CONCLUSIONS

Improvements in metabolic health in older adults with type 2 diabetes were mediated through improvements in body composition only if they were achieved through high-intensity PRT.

Body composition is central to insulin resistance (IR) and type 2 diabetes, projected to affect 435 million adults by 2030 (1). Lifestyle interventions are recommended to improve body composition (reduce adiposity, increase lean tissue) and, ultimately, to improve metabolic health. One lifestyle component is progressive resistance training (PRT), an anabolic exercise shown to improve body composition, as well as IR and glucose homeostasis in type 2 diabetes (2–4). Skeletal muscle hypertrophy is thought to mediate metabolic benefits of PRT by increasing the quality and quantity of skeletal muscle available for glucose storage. Increases in lean tissue have been associated with improvements in IR and glucose homeostasis (5,6).

In the Graded Resistance Exercise And Type 2 Diabetes in Older adults (GREAT2DO) study, we have shown strong relationships between body composition and homeostasis model assessment 2 of insulin resistance (HOMA2-IR) at baseline, before randomization to experimental (power training) or control (sham exercise) groups (7). The purpose of this interim report was to investigate changes in body composition after the first 12 months of training in relation to changes in IR or glucose homeostasis. We hypothesized that the experimental group would improve body composition (increased skeletal muscle mass [SkMM] and reduced visceral adipose tissue [VAT], reduced total fat mass [FM], and reduced intramyocellular lipid [IMCL]) compared with the control group. Furthermore, we hypothesized that across the entire cohort, beneficial shifts in body composition would lead to improvements in IR and glucose homeostasis.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

The GREAT2DO study is an ongoing trial investigating the efficacy of 6 years of PRT on IR and glucose homeostasis in older adults with type 2 diabetes. The first year was a randomized, double-blind, sham exercise controlled trial. After the initial year, participants were asked to continue training, with participants in the sham exercise control group crossed-over to high-intensity PRT. The data presented in this report are from the randomized controlled trial phase. Between July 2006 and November 2009, 103 participants were randomized to receive 12 months of high-intensity, high-velocity PRT or sham exercise (low-intensity, nonprogressive exercise), in addition to usual care. An investigator not involved with the study performed randomization. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in the Supplementary Materials. Written informed consent was obtained, and the protocol was approved by the Sydney South West Area Health Service and the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committees (Australian New Zealand clinical trial reg. no. 12606000436572).

Training protocol

The PRT group trained 3 days per week under supervision using pneumatic resistance equipment (Keiser Sports Health, Fresno, CA) at two sites. A version of PRT known as power training was used, in which the concentric contraction (lifting) was performed as quickly as possible, whereas the eccentric contraction (lowering) was performed over 4 s. The following exercises targeted large symmetrical muscle groups of the arms, legs, and trunk: seated row, chest press, leg press, knee extension, hip flexion, hip extension, and hip abduction. For each exercise, participants performed three sets of eight repetitions (two sets of eight on each leg for hip flexion, hip extension, and hip abduction). The intensity was set at 80% of the most recently determined one-repetition maximum, reassessed every 4 weeks. When one-repetition maximum testing was not feasible, resistances were increased by targeting a Borg scale rating of perceived exertion between 15 and 18.

The sham exercise group trained on the same equipment, 3 times per week, under supervision from the same trainers at different times of the day to remain blinded to the investigators' hypotheses, with both interventions offered as potentially beneficial. The resistance was set as low as possible and not progressed, and participants were instructed to perform concentric and eccentric contractions slowly.

Assessment protocol

Blinded outcome assessments were conducted at 0 and 12 months. Participants were required to withhold food, liquids, and medication for 12 h before metabolic testing. A 24-h food recall was performed on the day of the baseline assessment, and participants were asked to follow the same diet before subsequent assessments at 12 months. Assessments at 12 months were performed 72 h after completion of the final training session.

Anthropometry

Morning fasting stretch stature (wall-mounted Holtain stadiometer; Holtain Limited, Crymych Pembs, UK) and naked weight (weight in gown [kg] − weight of gown [kg]) were measured in triplicate to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.01 kg, respectively.

Body composition

FM and SkMM were determined using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) (RJL Systems, Clinton, MI) (8,9). Computed tomography (GE High-Speed CTI Scanner; Milwaukee, WI, used at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia) was used to quantify VAT (cm2), mid-thigh muscle cross-sectional area (cm2), and mid-thigh muscle attenuation (an index of intramyocellular lipid content; see Supplementary Materials for detailed methodology).

IR and glucose homeostasis

Serum glucose, C-peptide, and HbA1c were measured by a commercial pathology laboratory using standard assays (Douglass Hanley Moir, Sydney, Australia). HOMA2-IR was calculated with serum glucose and C-peptide values using the validated calculator (accessed at http://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk). C-peptide was used to avoid potential effects of fatty liver on insulin clearance in this cohort, which might distort HOMA2-IR calculations based on insulin (10). Sixteen participants were omitted from HOMA2-IR calculations because of insulin therapy, as it has not been validated in this cohort (11).

Analyses of changes in SkMM and VAT and changes in HOMA2-IR and HbA1c

Participants were stratified by change in SkMM over 12 months. Any change >0 was considered an increase (favorable); a change ≤0 was considered unfavorable. Participants also were stratified by change in VAT over 12 months. A change of <0 was considered a decrease (favorable), whereas a change of ≥0 was classified as unfavorable.

Statistical analyses

Normally distributed data are presented as mean ± SD and non-normally distributed data as median (range) or frequencies. Non-normally distributed data were log-transformed for use with parametric statistics. Comparisons of variables between groups were performed using a one-way ANOVA. A two-tailed repeated-measures ANOVA was used to determine time effect and group × time interaction. After this, ANCOVA models were constructed to determine the effects of group allocation and change in body composition (increase/decrease in SkMM or VAT) on changes in either HOMA2-IR or HbA1c (dependent variables). Potential confounders were identified as variables that were statistically different between groups at baseline (P < 0.05) and were related to the dependent variable of interest. Linear regressions were performed to determine relationships between the change scores of continuous variables and stratified by group allocation. Linear regressions were performed with potential confounders as the independent variables to determine if they may have had any significant effect on the changes in HOMA2-IR and HbA1c. Multiple linear regression and ANCOVA models were constructed with potential confounders as additional independent variables as needed. All available data from participants who completed their 12-month assessment, regardless of compliance, were used for analysis. A P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance, because all hypotheses were specified a priori. Statview 5.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used. Effect sizes were calculated using G*Power 3.1.2 (Kiel, Germany) (12).

RESULTS

Participant flow through the study can be found in the CONSORT flowchart in Supplementary Fig. 1. Participant characteristics can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Baseline relationships between HOMA2-IR and body composition have been previously reported (7). Three participants withdrew before commencing the intervention and thus were excluded from the analyses. At baseline, no differences were observed between the PRT group and sham group for HOMA2-IR (P = 0.14) or any body composition parameters (P = 0.38–79). The sham group tended to have higher HbA1c (P = 0.07), older age (P = 0.09), and longer duration of type 2 diabetes (P = 0.07). Overall, 86 participants attended the 12-month assessment, resulting in a drop-out rate of 14%. Compliance for the intervention was 78 ± 15%, with no significant difference observed between the PRT and sham group (P = 0.16).

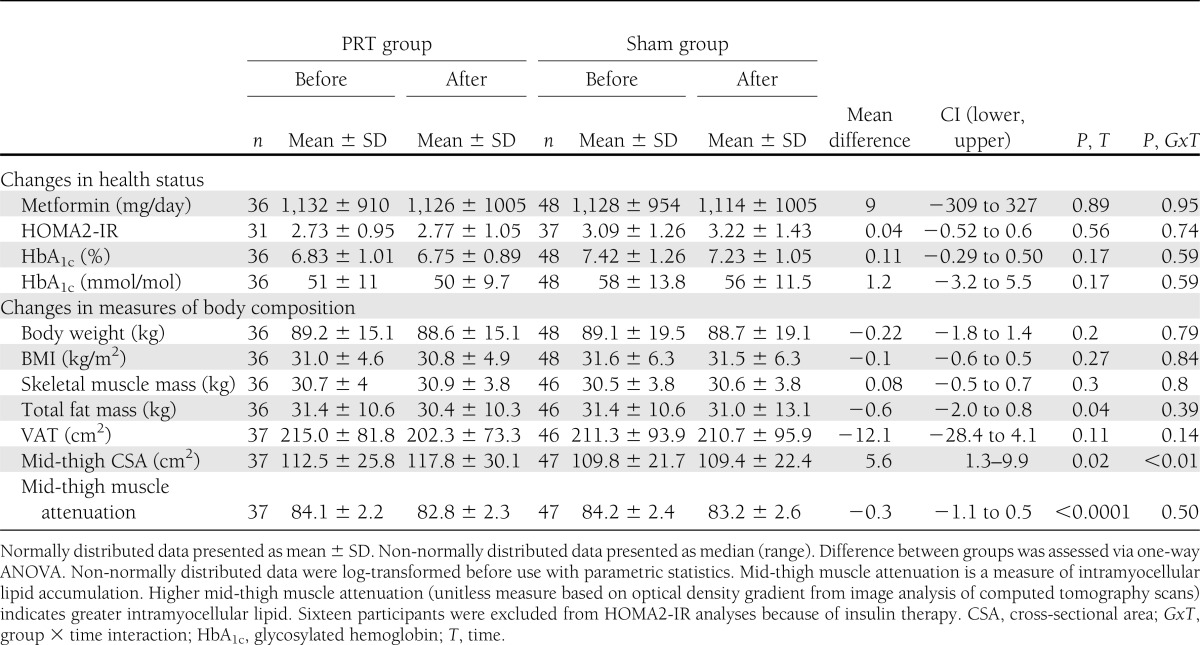

Changes in body composition

Body composition changes are shown in Table 1. As hypothesized, mid-thigh cross-sectional area increased significantly in the PRT group compared with the sham group (P < 0.01). Contrary to our hypotheses, there were no differences between the PRT and sham groups for changes in body weight, SkMM, FM, or VAT (P = 0.14–8). Over time, both groups showed similar significant reductions in FM and similar improvements in mid-thigh muscle attenuation (P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Changes in participant characteristics

Within the whole cohort, participants who increased SkMM significantly increased their body weight (+0.7 ± 3.7 kg) compared with those who had decreased SkMM (−1.4 ± 3.2 kg) (P < 0.05), with no effect of group allocation (P = 0.37). Participants who had increased and decreased SkMM showed a reduction in VAT (−2.7 ± 46.1 cm2 and −8.5 ± 26.7 cm2, respectively), again with no group difference (P = 0.13). However, after stratifying by change in SkMM (increase versus decrease), participants in the PRT group who increased SkMM tended to show a significant reduction in VAT (−17.3 ± 53.7cm2) compared with participants in the sham group who also had increased SkMM (+9.2 ± 35.9 cm2; P = 0.06).

Relationships between changes in body composition variables

Changes in FM and VAT were directly related in the PRT group (r = 0.69; P < 0.0001), but this relationship was attenuated and nonsignificant in the sham group (r = 0.26; P = 0.08) (Supplementary Fig. 2A and B).

Regression models

Relationships between changes in body composition and changes in HOMA2-IR.

Results are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Changes in SkMM were inversely related to changes in HOMA2-IR within the PRT group (r = −0.38; P = 0.04) (Fig. 1A), but not in the sham group (P = 0.35) (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, in the PRT group, changes in HOMA2-IR were directly related to changes in FM (r = 0.42; P = 0.02), as hypothesized (Fig. 1C). This relationship again was not present in the sham group (P = 0.51) (Fig. 1D). Finally, changes in VAT tended to be directly related to changes in HOMA2-IR in the PRT group (r = 0.31; P = 0.09) and inversely related in the sham group (r = −0.28; P = 0.1). No other body composition relationships were present (P = 0.15–79).

Figure 1.

Changes in body composition vs. changes in HOMA2-IR. A: Change in skeletal muscle mass and change in HOMA2-IR in the PRT group. B: Change in skeletal muscle mass and change in HOMA2-IR in the sham group. C: Change in total fat mass and change in HOMA2-IR in the PRT group. D: Change in total fat mass and change in HOMA2-IR in the sham group.

Relationship between changes in body composition and changes in HbA1c

Results are presented in Supplementary Table 2. As hypothesized, there was a direct relationship between increases (worsening) of mid-thigh muscle attenuation and HbA1c within the PRT group (r = 0.52; P = 0.001) (Fig. 2A), but this was not present in the sham group (P = 0.98) (Fig. 2B). No other body composition relationships were observed (P = 0.15–96).

Figure 2.

Change in mid-thigh muscle attenuation and change in HbA1c. A: Change in mid-thigh muscle attenuation and change in HbA1c in the PRT group. B: Change in mid-thigh muscle attenuation and change in HbA1c in the sham group.

ANCOVA models

Changes in SkMM and changes in HOMA2-IR.

An ANCOVA was performed with HOMA2-IR as the dependant variable, with exercise group allocation (PRT versus sham) and change in SkMM (increase versus decrease) as the grouping variables. Unexpectedly, no exercise group × change in SkMM interaction was present (P = 0.36). An ANCOVA model was then constructed with change SkMM (increase versus decrease) alone as the grouping factor, and then stratified by exercise group allocation (PRT versus sham). In this model, only those in the PRT group who had increased SkMM tended to have a decrease in HOMA2-IR (P = 0.05; effect size = 0.83) (12). No such relationship was observed in the sham group (P = 0.92). Finally, a third ANCOVA model was constructed with exercise group allocation (PRT versus sham) as the grouping factor, and then stratified by change in SkMM (increase versus decrease). In this model, those in the PRT group who had increased SkMM tended to have a decrease in HOMA2-IR compared with those who had increased SkMM in the sham group (P = 0.07). No such relationship was present in those who had decreased SkMM (P = 0.92) (Fig. 3A, depicted as percent change in HOMA2-IR).

Figure 3.

Change in body composition and changes in HOMA2-IR and HbA1c. A: Changes in skeletal muscle mass and changes in HOMA2-IR. B: Changes in skeletal muscle mass and changes in HbA1c. C: Changes in VAT and changes in HOMA2-IR. D: Changes in VAT and changes in HbA1c.

Changes in SkMM and changes in HbA1c.

An ANCOVA was performed with HbA1c as the dependant variable, with exercise group allocation (PRT versus sham) and change in SkMM (increase versus decrease) as the grouping variables. A trend for an exercise group × change SkMM interaction was present (P = 0.08). An ANCOVA model was then constructed with change SkMM (increase versus decrease) as the grouping factor, and stratified by exercise group allocation. As hypothesized, those who increased SkMM in the PRT group tended to reduce HbA1c compared with those in the PRT group who lost SkMM (P = 0.09). No such relationship was observed in the sham group (P = 0.32). Finally, a third ANCOVA model was constructed with exercise group allocation as the grouping factor, stratified by change in SkMM (increase versus decrease). As hypothesized, those in the PRT group who increased SkMM significantly reduced HbA1c compared with those who increased their SkMM in the sham group (P < 0.05). No relationship was found for those who decreased SkMM (P = 0.31) (Fig. 3B).

Changes in VAT and changes in HOMA2-IR.

An ANCOVA was performed with HOMA2-IR as the dependant variable, with exercise group allocation (PRT versus sham) and change in VAT (decrease versus increase) as the grouping variables. A significant exercise group × change in VAT interaction was present (P = 0.03). An ANCOVA model was then constructed with change in VAT (decrease versus increase) alone as the grouping factor, and then stratified by exercise group allocation. In this model, those who had decreased VAT in the PRT group tended to reduce HOMA2-IR compared with those who had increased VAT within the PRT group (P = 0.11). No relationship was observed in the sham group (P = 0.16). Finally, a third ANCOVA model was constructed with exercise group allocation as the grouping factor, and then stratified by change in VAT (decrease versus increase). In this model, those in the PRT group who had decreased VAT had significantly reduced HOMA2-IR compared with those who had decreased VAT in the sham group (P = 0.04). No such relationship was present in those who had increased VAT (P = 0.38) (Fig. 3C; depicted as percent change in HOMA2-IR).

Changes in VAT and changes in HbA1c.

An ANCOVA was performed with HbA1c as the dependant variable, with exercise group allocation (PRT versus sham) and change in VAT (decrease versus increase) as the grouping variables. No exercise group × change in VAT interaction was present (P = 0.99). Using ANCOVA models as described previously, no differential effect on HbA1c was observed between those who had decreased VAT in the PRT group and those in the PRT group who had increased VAT (P = 0.64). Similarly, there was no effect of VAT change on HbA1c change in the sham group (P = 0.24). Furthermore, no effect on HbA1c was observed in those in the PRT group who had decreased VAT compared with those who had decreased VAT in the sham group (P = 0.89). Similarly, increases in VAT did not influence changes in HbA1c between the PRT and sham groups (P = 0.38) (Fig. 3D).

CONCLUSIONS

We have shown that clinically relevant improvements in IR and glucose homeostasis in older adults with type 2 diabetes were predicted by improvements in body composition, but only if achieved via high-intensity PRT. Specifically, increases in SkMM achieved through high-intensity PRT were significantly associated with reductions in HbA1c and showed a similar trend for HOMA2-IR. Additionally, reductions in VAT achieved via PRT were strongly associated with improvements in HOMA2-IR. By contrast, these changes in body composition did not result in metabolic benefit if they occurred after sham (low-intensity) exercise. To date, this is the largest randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of PRT in older adults (older than 60 years) with type 2 diabetes. Previous studies in older Hispanic (2,3) and older Australian (4) adults were performed in smaller cohorts of 66 and 36 participants, respectively. In contrast to these particular studies, however, we show no significant reductions in HOMA2-IR or HbA1c associated with PRT at 12 months. However, the participants within our investigation had considerably lower HbA1c values (7.11%; 54 mmol/mol) compared with those particular investigations (7.8% and 62 mmol/mol [4]; 8.5% and 69 mmol/mol [2,3]). Interestingly, our regression and ANCOVA models show that improvements in HbA1c and IR were not dependant on changes in body weight, but rather improvements in body composition, notably, increases in SkMM and reductions in VAT and reductions in IMCL (for HbA1c). This is in agreement with a meta-analysis showing that improvements in glycemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes can occur independently of weight loss (13).

Role of SkMM in HbA1c

Reductions in HbA1c of a clinically meaningful magnitude (−0.38%; −4.2 mmol/mol) were seen only in those who had increased SkMM after high-intensity PRT, compared with those who did not have increased SkMM despite being in the same exercise group (+0.15%; +1.6 mmol/mol). In addition, those who gained skeletal muscle in the sham exercise group did not have improved glucose control either (HbA1c change +0.11%; +1.2 mmol/mol). These results suggest that increases in SkMM improved the metabolic health of participants, but only if they achieved this through high-intensity PRT. A 1% reduction in HbA1c has been associated with reductions in risk of diabetes complications of 21%, a 15% reduction in risk of future myocardial infarction, and a 37% reduction in microvascular complications (14). The reduction of −0.38% (−4.2 mmol/mol) after PRT is similar in magnitude to that recently reported in individuals prescribed a sulphonylurea (glimepride) in addition to their usual metformin dosage (−0.36%; −3.9 mmol/mol) (15). Dunstan et al. (4) showed significant reductions in HbA1c in individuals who participated in PRT in combination with a weight-loss diet compared with a weight-loss diet alone. Interestingly, both groups in that trial showed similar significant reductions in body fat; however, the group only using the weight-loss diet also showed reductions in lean body mass. This is in agreement with our data, which suggests that maintaining or improving SkMM through the use of high-intensity PRT is key to improving the metabolic health of older adults with type 2 diabetes.

Role of SkMM in IR

A nearly significant relationship between increases in SkMM and reductions in HOMA2-IR also was present. Post hoc power calculations show a large effect size of 0.83 for those who had increased SkMM in the PRT group versus decreases in SkMM in the PRT group. Regression analyses (Fig. 1A and B), notably, show that increases in SkMM were related to reductions in HOMA2-IR within the PRT group only (r = −0.38). Similar findings were reported by Brooks et al. (2), who found that improvements in HOMA-IR were related to increases in type 1 fiber cross-sectional area in those who participated in PRT (r = −0.5), with no relationship observed in those randomized to a nonexercise control group. These findings suggest that improvements in hepatic IR are dependent on the amount of increase in SkMM.

Because HOMA2-IR is a measure of hepatic IR, reductions in HOMA2-IR through increases in SkMM are likely to be less direct than those seen with HbA1c. The HOMA index is clinically relevant because it has been shown to reflect whole-body insulin sensitivity as measured in clamp studies (16,17), and fasting hyperglycemia is predictive of cardiovascular morbidity (18). Therefore, further investigations into the mechanism by which increases in SkMM lead to reductions in HOMA2-IR are needed. IR in skeletal muscle has been shown to directly cause an increase in hepatic de novo lipogenesis independent of VAT (19), potentially contributing to the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, whereas improvements in skeletal muscle IR through exercise have been shown to ameliorate de novo lipogenesis (20).

Role of IMCL

Despite similar reductions in IMCL observed within the PRT and sham groups (Table 1), reductions in IMCL were only related to improvements in HbA1c in the PRT group (Fig. 2A), not in the sham group (Fig. 2B). Notably, 28% of the variance in the reduction in HbA1c was explained by reduction in IMCL within the PRT group. Impaired fatty acid oxidation can lead to accumulation of metabolites (21–23), which are known to impair insulin signaling. It is possible that the reduction in IMCL through the use of high-intensity PRT improved insulin signaling within skeletal muscle, and thus contributed to the improvements in glycemic control. Because the magnitude of the reduction in IMCL between the PRT and sham groups was not different, it again suggests that there was an exercise-dependent effect on reductions in IMCL and subsequent reductions in HbA1c. It is possible that high-intensity PRT increased mitochondrial oxidative capacity, consequently improving fatty acid oxidation (24). Together with the heightened metabolic demand of high-intensity PRT, this may have resulted in a reduction in IMCL via a different pathway than that seen within the sham group.

Role of adipose tissue

Reductions in FM also were related to improvements in IR within the PRT group only (Fig. 1C and D), despite similar reductions in FM in both groups. It is likely that this was mediated through preferential loss of VAT within the PRT group. The PRT group had significantly reduced VAT compared with the sham group (Table 1); also, reductions in VAT within the PRT group predicted reductions in FM (r = 0.69), although this relationship was not significant in the sham group (Supplementary Fig. 2A and B). This highlights a preferential loss of VAT, rather than peripheral depots, with high-intensity PRT. Furthermore, Fig. 3C shows that those with reductions in VAT within the PRT group had significantly reduced IR compared with those who had increased VAT within the PRT group. VAT has been shown to correlate with hepatic steatosis (25) and systemic inflammation, both of which are related to hepatic IR (26,27). These pathways may explain the observed relationship between decreased VAT after PRT and improvements in hepatic IR.

Limitations and future directions

The most interesting finding from this investigation is that despite similar changes in SkMM in the participants within the PRT and sham groups, improvements in IR and HbA1c were only present in those randomized to the PRT group. The exercise intensity within the sham group was likely insufficient to promote hypertrophy; therefore, gains in SkMM within these participants would be attributed to other factors, most probably overnutrition. In support of this, those who gained SkMM within the sham group increased their VAT by 9.2 cm2, compared with individuals in the PRT group who gained SkMM, and showed a reduction in VAT of −17.3 cm2. Thus, favorable alterations in both skeletal muscle and adipose tissue mass and distribution mediated through high-intensity PRT can result in improvements in the metabolic health of individuals with type 2 diabetes. However, the mechanistic pathways require further examination and were beyond the scope of this investigation. Perhaps most importantly, 50 and 41% of participants did not have beneficially modified SkMM and VAT, respectively, in response to high-intensity PRT. Identifying responders to high-intensity PRT may allow for individually tailored lifestyle interventions in the future and development of cointerventions to optimize favorable body composition adaptations. The presence of a sex effect is also possible. However, the current investigation was not sufficiently powered to warrant investigation into any sex-specific adaptations, but they should be considered in future investigation. Finally, consideration of the potential adverse effects of PRT is warranted, including the possibility of increases in arterial stiffness, a significant predictor of future cardiovascular mortality (28). However, a recent meta-analysis has shown that PRT only affects arterial stiffness in younger adults, with these effects not present among older adults (29).

It remains unclear why participants randomized to the sham group, who lost skeletal muscle mass, showed reductions in HbA1c (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the mechanism behind the loss in IMCL within the sham group (Supplementary Table 2) and why this was not associated with improvements in HbA1c or IR require investigation. It is possible that dietary factors or changes in habitual levels of physical activity may explain these findings. Data analysis regarding these variables is in progress.

Because of funding constraints and equipment availability, whole-body SkMM and fat mass were estimated using BIA, although regional body composition was performed using state-of-the-art computed tomography methodology. Furthermore, IR was determined using HOMA2-IR, reflective of hepatic IR, as opposed to a whole-body measure. Appropriately powered studies of similar design should be used that utilize more direct measures of whole-body composition (such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) and IR (hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp).

In conclusion, both increases in SkMM and reductions in VAT and IMCL achieved through high-intensity PRT improved IR and glucose homeostasis in a cohort of older adults with type 2 diabetes. Notably, increased SkMM or decreased VAT and IMCL accumulation achieved without anabolic exercise did not have the same metabolic benefit. Future investigations should be directed toward understanding the heterogeneity in body composition adaptations to anabolic exercise in older adults with type 2 diabetes and to developing strategies to maximize these beneficial changes to improve metabolic health and future disease risk in this vulnerable cohort.

Acknowledgments

The GREAT2DO study was funded by project grant 512381 from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), and grants from The Australian Diabetes Society and Diabetes Australia. Y.M. was supported by the Australian Postgraduate Award Scholarship. Y.W. was supported by University of Sydney International Postgraduate Research Scholarship.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Y.M. assisted with data collection and participant training, primarily analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. S.K., R.Z., J.M., and N.d.V. assisted with participant training. K.R., D.S., M.K.B., A.O'S., N.S., and B.T.B. assisted with data analysis, contributed to the discussion, and edited the manuscript. K.A.A. and Y.W. assisted with data collection. M.C. and S.N.B. reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.A.F.S. supervised data analyses, supervised and assisted with data collection, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Y.M. and M.A.F.S. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Parts of this study were presented as a poster at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, San Diego, California, 14–18 November 2012.

The authors thank Freshwater Health and Fitness for the use of their gym facilities, Keiser Sports Health Ltd for donations of resistance training equipment, and participants for their generosity of time and spirit.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc12-2196/-/DC1.

Australian New Zealand clinical trial reg. no. ANZCTRN 12606000436572, www.anzctr.org.au

References

- 1.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:4–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks N, Layne JE, Gordon PL, Roubenoff R, Nelson ME, Castaneda-Sceppa C. Strength training improves muscle quality and insulin sensitivity in Hispanic older adults with type 2 diabetes. Int J Med Sci 2007;4:19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castaneda C, Layne JE, Munoz-Orians L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of resistance exercise training to improve glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25:2335–2341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunstan DW, Daly RM, Owen N, et al. High-intensity resistance training improves glycemic control in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1729–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuff DJ, Meneilly GS, Martin A, Ignaszewski A, Tildesley HD, Frohlich JJ. Effective exercise modality to reduce insulin resistance in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2977–2982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldi JC, Snowling N. Resistance training improves glycaemic control in obese type 2 diabetic men. Int J Sports Med 2003;24:419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posters: T5-Clinical Practice and Multi Disciplinary Management Obesity Facts 2012;5(Suppl 1):178–234 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Baumgartner RN, Ross R. Estimation of skeletal muscle mass by bioelectrical impedance analysis. J Appl Physiol 2000;89:465–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lukaski HC, Bolonchuk WW, Hall CB, Siders WA. Validation of tetrapolar bioelectrical impedance method to assess human body composition. J Appl Physiol 1986;60:1327–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinn DH, Gwak GY, Park HN, et al. Ultrasonographically detected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is an independent predictor for identifying patients with insulin resistance in non-obese, non-diabetic middle-aged Asian adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:561–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1487–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner AG. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulé NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP, Wells GA, Sigal RJ. Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. JAMA 2001;286:1218–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HAW, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000;321:405–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallwitz B, Rosenstock J, Rauch T, et al. 2-year efficacy and safety of linagliptin compared with glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin: a randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012;380:475–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emoto M, Nishizawa Y, Maekawa K, et al. Homeostasis model assessment as a clinical index of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients treated with sulfonylureas. Diabetes Care 1999;22:818–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonora E, Targher G, Alberiche M, et al. Homeostasis model assessment closely mirrors the glucose clamp technique in the assessment of insulin sensitivity: studies in subjects with various degrees of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 2000;23:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levitzky YS, Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, et al. Impact of impaired fasting glucose on cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:264–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Savage DB, et al. The role of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:12587–12594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabøl R, Petersen KF, Dufour S, Flannery C, Shulman GI. Reversal of muscle insulin resistance with exercise reduces postprandial hepatic de novo lipogenesis in insulin resistant individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:13705–13709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Straczkowski M, Kowalska I. The role of skeletal muscle sphingolipids in the development of insulin resistance. Rev Diabet Stud 2008;5:13–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corcoran MP, Lamon-Fava S, Fielding RA. Skeletal muscle lipid deposition and insulin resistance: effect of dietary fatty acids and exercise. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:662–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perseghin G. Muscle lipid metabolism in the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Lipidol 2005;16:416–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarnopolsky MA. Mitochondrial DNA shifting in older adults following resistance exercise training. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2009;34:348–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perseghin G. Lipids in the wrong place: visceral fat and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl 2):S367–S370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastard JP, Maachi M, Lagathu C, et al. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Eur Cytokine Netw 2006;17:4–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Preis SR, Massaro JM, Robins SJ, et al. Abdominal subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue and insulin resistance in the Framingham heart study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:2191–2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruickshank K, Riste L, Anderson SG, Wright JS, Dunn G, Gosling RG. Aortic pulse-wave velocity and its relationship to mortality in diabetes and glucose intolerance: an integrated index of vascular function? Circulation 2002;106:2085–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyachi M. Effects of resistance training on arterial stiffness: a meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:393–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]