Abstract

Selective autophagy can be mediated via receptor molecules that link specific cargoes to the autophagosomal membranes decorated by ubiquitin-like microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) modifiers. Although several autophagy receptors have been identified, little is known about mechanisms controlling their functions in vivo. In this work, we found that phosphorylation of an autophagy receptor, optineurin, promoted selective autophagy of ubiquitin-coated cytosolic Salmonella enterica. The protein kinase TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1) phosphorylated optineurin on serine-177, enhancing LC3 binding affinity and autophagic clearance of cytosolic Salmonella. Conversely, ubiquitin- or LC3-binding optineurin mutants and silencing of optineurin or TBK1 impaired Salmonella autophagy, resulting in increased intracellular bacterial proliferation. We propose that phosphorylation of autophagy receptors might be a general mechanism for regulation of cargo-selective autophagy.

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is an evolutionarily conserved catabolic process by which cells deliver bulk cytosolic components for degradation to the lysosome (1–4). Selectivity in cargo targeting is mediated via autophagy receptors that simultaneously bind cargoes and autophagy modifiers, autophagy-related protein 8 (ATG8)/ microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3)/γ-aminobutyric acid receptor-associated protein (GABARAP) proteins, which are conjugated to the autophagosomal membranes (5, 6). The regulatory mechanisms controlling the spatiotemporal dynamics of the autophagy receptor-target interaction in cells remain unclear (7).

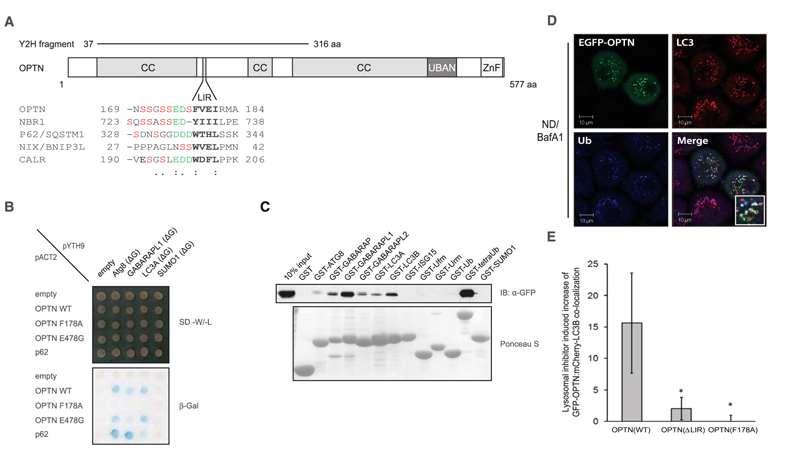

Multiple autophagy receptors have been identified with the yeast two-hybrid system (8, 9), which included an N-terminal fragment of optineurin (OPTN), a ubiquitin-binding protein also known as NF-κB essential modulator–related protein (Fig. 1, A and B). The specific interactions between OPTN and LC3/GABARAP proteins were verified by pull-down assays in mammalian cells, directed yeast two-hybrid transformations, and in vitro using purified proteins (Fig. 1C and fig. S1, A and B) (10). OPTN bound to ubiquitin chains and autophagy modifiers ATG8/LC3/GABARAP proteins but not to mono-ubiquitin or other ubiquitin-like proteins (Fig. 1C and fig. S1C). Deletion mapping of the N-terminal region of OPTN identified an LC3 interacting motif (LIR), a linear tetrapeptide sequence present in known autophagy receptors that binds directly to LC3/GABARAP modifiers (9, 11, 12). The LIR was located between the coiled-coil domains of OPTN encompassing amino acids 169 to 209 (Fig. 1A) and was essential for in vitro and in vivo binding between OPTN and LC3/GABARAP (Fig. 1, B and C, and figs. S1A and S2A). Single point mutations at either OPTN Phe178→Ala178 (F178A) or I181A (13), corresponding to the WxxL of p62, were sufficient to abrogate the interaction with LC3/GABARAP proteins, whereas these mutants were still able to bind to linear ubiquitin chains fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST-4xUb) (Fig. 1A and fig. S2B).

Fig. 1.

OPTN is an autophagy receptor. (A) Schematic representation of OPTN’s domain architecture. An alignment of known LIR motifs is shown underneath, with the tetra-peptide LIR highlighted in bold. N-terminal end of the LIR, acidic residues (green), and potential phosphorylation sites (red) are shown and are considered part of an extended LIR. CC, coiled-coil; aa, amino acids; ZnF, zinc finger. (B) Directed yeast two-hybrid of bait proteins (pYTH9: scAtg8, GABARAPL-1, LC3A, and SUMO1) and prey OPTN variants [pACT2: full-length OPTN WT, LIR mutant (F178A) or ubiquitin binding mutant (E478G)]. p62 LIR (aa 311 to 444) was also included. Interaction was assessed using a β-galactosidase assay. (C) GST pull-down assay of EGFP-OPTN from stable MCF-7 cells using GST or GST-ubiquitin like proteins. IB, immunoblot. (D) Representative confocal images of HeLa cells overexpressing EGFP-OPTN and treated with nutrient deprivation plus lysosomal bafilomycin A1 (ND/BafA1) localized to endogenous LC3B and ubiquitin (inset). Scale bars, 10 μm. (E) Colocalization quantification of ≥1000 cells expressing mCherry-LC3B and EGFP-OPTN [WT and deletion; ΔLIR (Δ178-181) or point mutation F178A] within single cells by ImageStream analysis. Error bars indicate mean ± SD; n = 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; one-tailed, paired t test.

OPTN localized in LC3-positive vesicles upon induction of autophagy (Fig. 1D and figs. S1D and S3, A to F). An LC3-binding–deficient mutant of OPTN (OPTN F178A) did not cluster into cytoplasmic LC3 structures under autophagy-inducing conditions (fig. S3B). Surprisingly, this was also the case for ubiquitin-binding–deficient OPTN variants (fig. S3C). The localization of mCherry-LC3B with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)–OPTN wild-type (WT), ΔLIR, and F178A mutants was quantified under nutrient deprivation–induced autophagy conditions in human MCF-7 cells with the use of high-sampling (>1000 cells per condition), high-resolution imaging (fig. S3, D and E). Quantification of the population responses revealed that mCherry-LC3B: EGFP-OPTN WT colocalization was enhanced in cells treated with bafilomycin A1 (Fig. 1E). Co-localization of EGFP-OPTN F178A and EGFP-OPTN ΔLIR with mCherry-LC3B was significantly suppressed compared with WT EGFP-OPTN (Fig. 1E). Thus, OPTN is an autophagy receptor that binds and localizes with LC3/GABARAP via a phenylalanine-containing LIR motif and ubiquitin via its ubiquitin binding in ABIN and NEMO (UBAN) domains (14).

The hydrophobic core sequence of the LIR motif in OPTN is preceded by multiple serine residues, which are evolutionarily conserved (fig. S4A). One prime kinase candidate was the Tank-binding kinase (TBK1), due to the presence of a conserved TBK1 consensus sequence (SxxxpS). Indeed, TBK1 binds directly to OPTN (15) and coexpression of OPTN together with TBK1 in vivo increased OPTN phosphorylation, which was reversed by either λ-phosphatase treatment or a TBK1 inhibitor (BX795) (fig. S4, B to D) (16). Moreover, recombinant TBK1 phosphorylated purified GST-OPTN in an in vitro kinase assay (fig. S4, E and F), indicating that TBK1 is a bona fide kinase that directly phosphorylates OPTN.

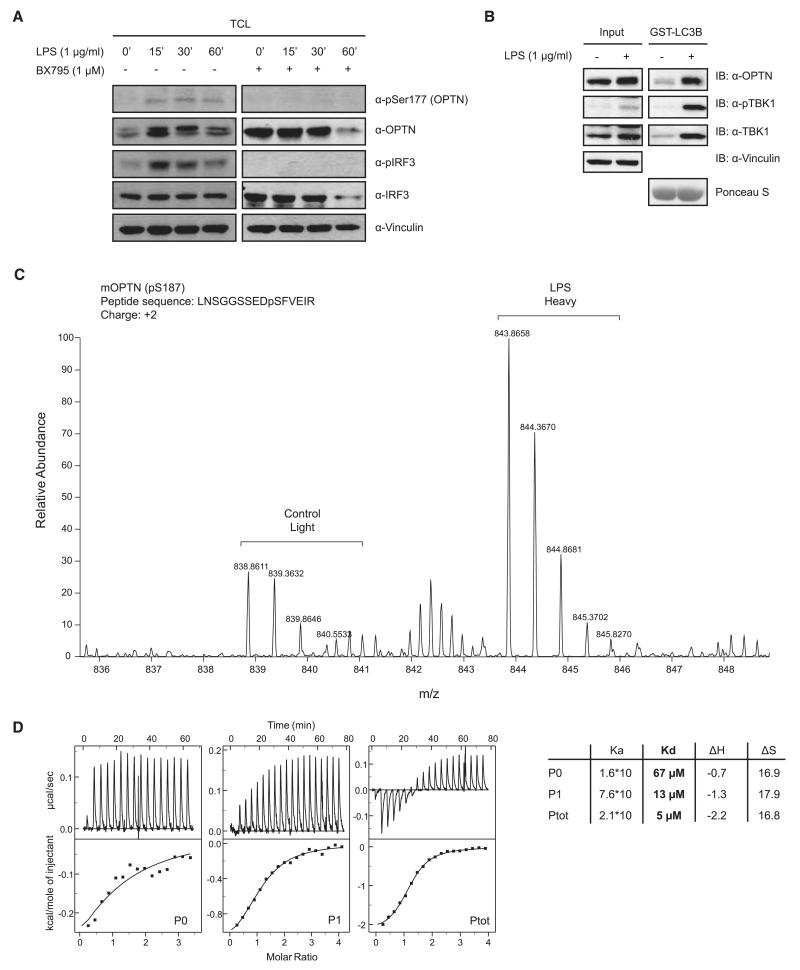

To identify the TBK1 phosphorylation sites on OPTN, we performed stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)–based mass spectrometry (fig. S5A). Phosphorylated Ser177, adjacent to the OPTN LIR motif (Fig. 1A and fig. S4A), showed substantially higher SILAC intensity in cells coexpressing TBK1 in comparison with control (fig. S5B). Multiple phosphorylated LIR-peptides with up to three phosphorylated groups were identified in the presence of overexpressed TBK1. Endogenous OPTN was phosphorylated at Ser177 (measured by using anti-pSer177 OPTN antibody) (fig. S6A) after stimulation of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with microbe-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which activates TBK1 via Toll-like receptor 4 (Fig. 2A). OPTN and phospho-TBK1 (active) formed an inducible complex with GST-LC3 (Fig. 2B). Next, phosphorylated OPTN complexed with the autophagy modifier GST-GABARAPL1 was analyzed using SILAC-labeled MEFs from untreated (light) or LPS-stimulated MEFs (heavy). The most abundant phosphopeptide of OPTN identified was a LIR spanning fragment, which carried a phosphate group at mouse OPTN Ser187 corresponding to human Ser177 (Fig. 2C and fig. S4A). SILAC-based relative quantification showed an increased intensity of the peptide from LPS-stimulated cells in comparison to control cells (no LPS treatment) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

TBK1 phosphorylates OPTN within the extended LIR motif. (A) MEFs were stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS in the presence or absence of 1 μM BX795 for the indicated time points. Cell lysates were analyzed with antibodies against OPTN, phospho-OPTN (Ser177), total IRF3, and phospho-IRF3 (pSer396). pSer177 OPTN was lost after inhibition of TBK1 with BX795. (B) MEFs were left untreated or stimulated with LPS for 30 min, lysed, and endogenous OPTN precipitated with GST-LCB. (C) SILAC-labeled untreated or 30-min LPS-stimulated MEF cells and OPTN precipitated with GST-GABARAPL1 and analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS). MS spectrum showed enriched phosphor-Ser177 OPTN in LPS-stimulated cells compared with control. (D) ITC titration of LC3B with OPTN peptides—namely LIR_P0 (no phosphorylation), LIR_P1 (pSer177) (middle), and LIR_Ptot (all serines phosphorylated, left)—corresponding to human OPTN amino acids 169 to 184 (right). Raw data (upper boxes) and the integrated heat per titration step (points) and best-fit curves (lower panels) are shown. Calculations assume a one-site binding model. The dissociation constant (Kd), in the presence of phosphorylated OPTN serine residues showed a 5- to 13-fold decrease indicating enhanced affinity of LC3B to OPTN LIR. Ka, acid constant; ΔH, change in enthalpy; ΔS, change in entropy.

Next, we investigated the potential impact of phosphorylation of the LIR motif on the interaction of OPTN with LC3 proteins. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments with LC3B and three different peptides, spanning OPTN’s LIR motif and the preceding (N-terminal) serine-rich region, representing different states of OPTN LIR phosphorylation (P0, no phosphorylation; P1, pSer177; and Ptot, all five serines being phosphorylated) revealed that the binding affinity of OPTN LIR to LC3B was considerably enhanced by the presence of phosphate groups (Fig. 2D). The dissociation constant (Kd) decreased from 67 μM for the non–phosphorylated state (P0) to 13 μM for the monophosphorylated form (P1) and to 5 μM for the penta-phosphorylated form (Ptot) (Fig. 2D). Nuclear magnetic resonance titration experiments revealed that phospho-OPTN peptide does not substantially change the binding mode, but that the presence of phospho-serines preceding the LIR alters hydrogen bond formation and increases binding affinity (fig. S7A).

Using phospho-mimicking OPTN mutants with serine to aspartic acid (5xS->D) or glutamic acid (5xS->E) and nonphosphorylatable alanine (5xS->A), we tested the interaction of OPTN and LC3B. Both phospho-mimicking versions of OPTN bound to LC3B with a higher affinity than OPTN wild type (fig. S7B). In contrast, the OPTN 5xS->A mutant was strongly impaired in its ability to bind LC3B, demonstrating that additional negative charges contribute to binding of OPTN to LC3B in cells (fig. S7B). Accordingly, LC3B coimmunoprecipitated more efficiently phosphorylated OPTN (induced by TBK1 coexpression) than unmodified OPTN (fig. S7C).

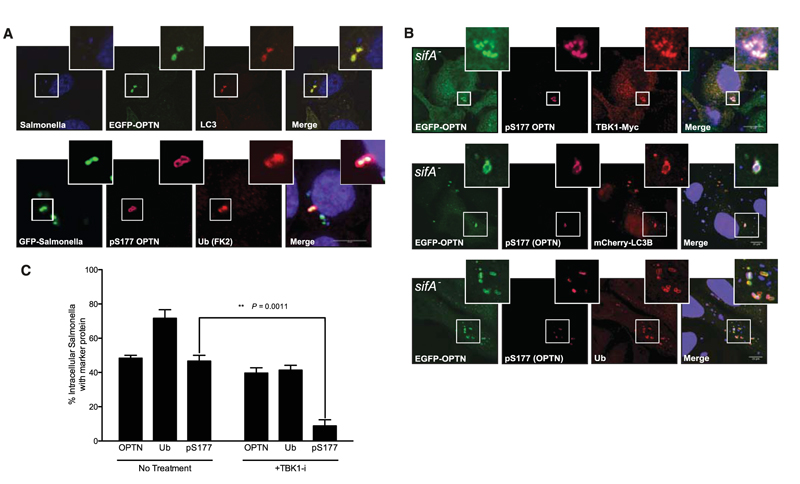

TBK1 is activated by the cell wall components of Gram-negative bacteria (such as LPS), and TBK1 kinase activity is required to maintain the integrity of Salmonella-containing vacuoles (SCVs) and restrict Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) growth in the cytosol (17, 18). Upon infection, most Salmonella reside in SCVs. However, a fraction of Salmonella escape from the SCVs to the host cell cytosol where they hyperproliferate, which has been observed in vivo in the gall bladder epithelium of infected mice and is likely to play an important role in Salmonella dissemination to new hosts (19). As a cellular defense mechanism, cytosolic Salmonella is rapidly coated with ubiquitin (20) and delivered to the autophagy clearance pathway (17, 18). Therefore, we tested a potential role for OPTN in regulating autophagy of cytosolic Salmonella. In Salmonella-infected HeLa cells, OPTN was recruited to a subpopulation of cytosolic bacteria stained with antibodies against LC3 and ubiquitin (anti-LC3 and anti-ubiquitin) (Fig. 3A), but not with LAMP1 (a marker for the SCV) (fig. S8A). A ubiquitin-binding–deficient OPTN mutant (DF474, 475NA) failed to be recruited to Salmonella (fig. S8, B and D), whereas the LC3-binding–deficient mutant OPTN F178Awas readily detected around Salmonella (fig. S8, C and D). To test OPTN recruitment to cytosolic Salmonella, we used an EGFP-expressing Salmonella sifA− mutant that resides predominantly in the cytosol (21). OPTN localized with TBK1, LC3, and ubiquitin to cytosolic Salmonella (Fig. 3B), but not LAMP1, a marker for Salmonella SCV (fig. S8E). OPTN that was recruited to cytosolic Salmonella (both WT and sifA) was phosphorylated on Ser177, as monitored by an anti-pSer177 OPTN antibody (Fig. 3, A and B), and inhibition of TBK1 using BX795, a specific inhibitor (19), led to loss of phosphorylated OPTN (pS177), but not total OPTN to ubiquitin positive, cytosolic Salmonella (Fig. 3C and fig. S8E). Thus, OPTN can be recruited to ubiquitinated cytosolic Salmonella, with TBK1, which subsequently phosphorylates OPTN, resulting in enhanced LC3 binding. Consistent with these observations, a nonphosphorylatable OPTN mutant (5xS->A), when transfected in cells, failed to direct LC3 to Salmonella as efficiently as a phosphomimicking OPTN variant (5xS->D) (fig. S8F).

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylated OPTN colocalizes with ubiquitin- and LC3B-positive cytosolic Salmonella. (A) Confocal images of HeLa cells expressing EGFP-OPTN and mCherry-LC3B 4 hours post infection (hpi) with S. Typhimurium (SL1344). EGFP-OPTN colocalizes with LC3B (upper panel) on a fraction of Salmonella. Phospho-Ser177 OPTN localizes to EGFP-expressing Salmonella (MW57) with Ub at 1 hpi. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) EGFP-OPTN (green) and pS177 OPTN (purple) colocalized with TBK1 (upper panel), mCherry-LC3B (middle panel), and ubiquitin (lower panel) at 4 hpi with cytosolic Salmonella sifA (blue). (C) Quantification of colocalization of cytosolic Salmonella sifA– with EGFP-OPTN, ubiquitin, and pSer177 OPTN from cells represented in (B), as compared with cells treated with 1 μM BX795. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

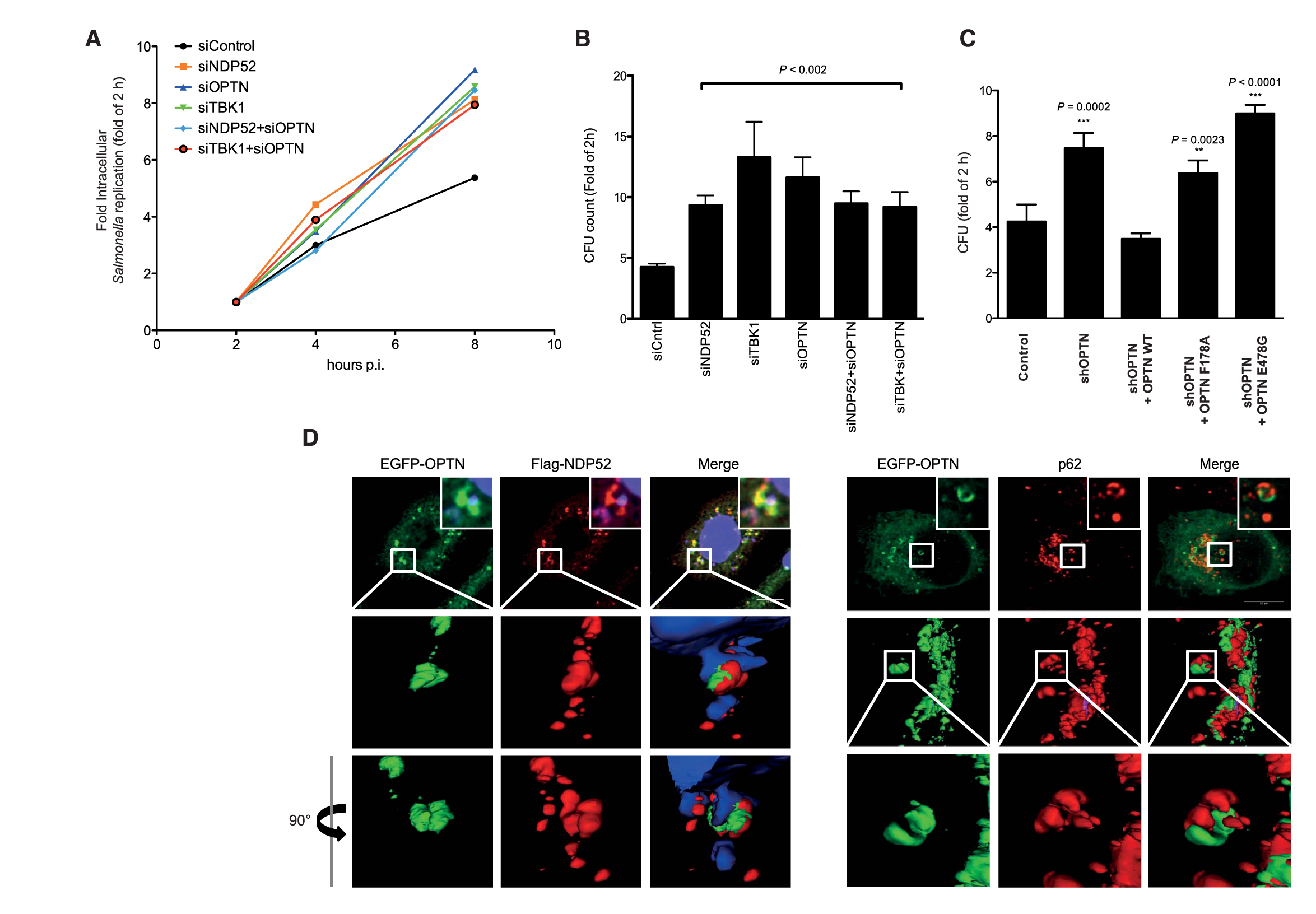

Depletion of OPTN in Hela cells, either transiently by small interfering RNA (siRNA) or stably by short hairpin RNA (shRNA), resulted in enhanced proliferation of Salmonella as compared with control siRNA or shRNA (Fig. 4, A to C). Introduction of an shRNA-resistant OPTN gene resulted in substantial suppression of intracellular Salmonella proliferation (Fig. 4C). However, a ubiquitin-binding–deficient OPTN mutant (E478G) or LIR mutant (F178A) was not able to rescue Salmonella suppression to the level of WT OPTN (Fig. 4C). Thus, OPTN requires both Ub and LC3-binding domains to restrict bacterial growth in cells and can therefore be classified as a bona fide autophagy receptor for ubiquitinated bacteria.

Fig. 4.

Salmonella proliferation is enhanced in the absence of OPTN in vivo. (A) HeLa cells transfected with indicated siRNAs were infected with Salmonella (SL1344) and lysed at the indicated time points post-infection, and bacterial colonies were counted on selective agar plates. (B) Numbers of bacteria recovered from HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs and infected with Salmonella for 8 hpi. Intracellular Salmonella replication was calculated as fold increase at the 2-hour time point. Depletion of OPTN, NDP52, or TBK1 resulted in increased Salmonella intracellular replication. Error bars indicate mean ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.002, two-tailed t test. CFU, colony-forming units. (C) ShRNA OPTN-depleted HeLa cells were transiently reconstituted with shRNA-resistant OPTN WT, shR-OPTN F178A, and shR-OPTN E478G. Both LIR mutants and Ub-binding mutants of OPTN failed to rescue OPTN-depleted HeLa cells 8 hpi compared with OPTN WT. Error bars indicate mean ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments. (D) Three-dimensional reconstitution of confocal image z-stacks of Salmonella-infected HeLa cells at 4 hpi. EGFP-OPTN WT (green), NDP52 (red, left panel), and endogenous p62 (red right panel) form distinct “patches” on the surface of cytosolic Salmonella.

Salmonella growth restriction mediated by both autophagy receptors OPTN and NDP52 appears comparable (Fig. 4, A and B), and both proteins colocalized to cytosolic bacteria (Fig. 3A) (18, 22). Therefore, we tested whether they are directed to the same or different populations of cytosolic bacteria. OPTN targeted the same bacteria as NDP52 and p62 (Fig. 4D) However, OPTN and NDP52 colocalized to the same patches on Salmonella, whereas OPTN and p62 were present on different subdomains (Fig. 4D). Similarly, NDP52 and p62 also formed nonoverlapping subdomains around the ubiquitinated bacteria, as observed previously (23). Thus, NDP52 and OPTN localize to common microdomains on the surface of ubiquitinated bacteria separate from p62. Silencing either OPTN/NDP52 (Fig. 4A) or NDP52/p62 (23) had no additive effect in increasing bacterial proliferation, indicating that autophagy receptors (OPTN, NDP52, and p62) act along the same pathway and are mutually dependent in promoting autophagy of cytosolic bacteria.

Thus, OPTN appears to function in innate immunity against cytosolic bacteria by linking the TBK1 signaling pathway to autophagic elimination of cytosolic pathogens. TBK1 appears to be recruited to Salmonella via OPTN UBAN domain binding to ubiquitin-decorated bacteria, where TBK1 becomes activated and mediates phosphorylation of Ser177 adjacent to the OPTN’s LIR motif. In such a model, phosphorylation of an autophagy receptor acts as a molecular trigger to promote autophagic clearance of cytosolic bacteria. Multiple Salmonella-sensing receptors, including p62, NDP52, and OPTN, bind to ubiquitin-coated Salmonella. The ability of their respective UBDs to bind to different ubiquitin chains might account for partitioning of autophagy receptors to different subdomains on the bacterium (fig. S9). The identity of the E3 ubiquitin ligase and, consequently, which type of ubiquitin chains are conjugated to the bacterial surface components, is still unknown. Thus, whether OPTN, p62, and NDP52 are recruited to subdomains by interaction with different ubiquitin chains or via other complexes on Salmonella surface remains an open question.

This study also indicates more general and diverse roles for phosphorylation in the control of signaling networks mediated by ubiquitin or its related modifiers. For example, small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) interaction with its respective SUMO-interacting motif also enhances binding affinity (24), similar to LIR modification. Notably, a number of known autophagy receptors contain conserved serine residues adjacent to their LIRs, including NIX and NBR1, indicating a potentially broader impact of phosphorylation of autophagy processes. Interestingly, LC3A and LC3B have phosphorylated serine/threonine residues in their N-terminal extensions that are crucial for the interaction with LIR motifs (25, 26). Taken together, phosphorylation of ubiquitin-like modifiers and their binding domains brings another layer of complexity in controlling ubiquitin and autophagy signaling networks (27).

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Cohen, S. Mueller, K. Rajalingam, C. Behrends, and the members of Dikic laboratory for constructive comments and critical reading of the manuscript; P. Cohen for OPTN and TBK1 reagents; and V. Kirkin for the initial yeast two-hybrid screens. This work was supported by grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Cluster of Excellence “Macromolecular Complexes” of the Goethe University Frankfurt (EXC115), the Landes-Offensive zur Entwicklung Wissentschaftlich-ökonomischer Exzellenz–funded Onkogene Signaltransduktion Frankfurt network, and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement no. (250241-LineUb) to I.D. and partly by Swiss National Fonds (3100A0-121834/1) to D.B. The Center for Protein Research is funded by a generous grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation. J.K. is supported by a scholarship from the Split, Croatia, government, S.W. by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Danish Council for Independent Research (FSS: 10-085134), N.R.B. by the Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association, and H.F. by Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A-121834).

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1205405/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S9

Table 1

References

References and Notes

- 1.Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:458. doi: 10.1038/nrm2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:124. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Nature. 2011;469:323. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deretic V. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:252. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirkin V, McEwan DG, Novak I, Dikic I. Mol. Cell. 2009;34:259. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraft C, Peter M, Hofmann K. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:836. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McEwan DG, Dikic I. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:195. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novak I, et al. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:45. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkin V, et al. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:505. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 11.Pankiv S, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behrends C, Sowa ME, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Nature. 2010;466:68. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues are as follows: A, Ala; D, Asp; E, Glu; F, Phe; G, Gly; I, Ile; and S, Ser.

- 14.Wagner S, et al. Oncogene. 2008;27:3739. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morton S, Hesson L, Peggie M, Cohen P. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:997. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark K, Plater L, Peggie M, Cohen P. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:14136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radtke AL, Delbridge LM, Balachandran S, Barber GN, O’Riordan MX. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e29. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurston TL, Ryzhakov G, Bloor S, von Muhlinen N, Randow F. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:1215. doi: 10.1038/ni.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knodler LA, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:17733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006098107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perrin AJ, Jiang X, Birmingham CL, So NS, Brumell JH. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:806. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beuzón CR, et al. EMBO J. 2000;19:3235. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng YT, et al. J. Immunol. 2009;183:5909. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cemma M, Kim PK, Brumell JH. Autophagy. 2011;7:341. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stehmeier P, Muller S. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:400. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang H, Cheng D, Liu W, Peng J, Feng J. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;395:471. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherra SJ, 3rd, et al. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:533. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeda F, Crosetto N, Dikic I. Cell. 2010;143:677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]