Abstract

The dopamine transporter (DAT) clears the extracellular dopamine released during neurotransmission and is a major target for both therapeutic and addictive psychostimulant amphetamines. Amphetamine exposure or activation of protein kinase C (PKC) by the phorbol ester PMA has been shown to down-regulate cell surface DAT. However, in dopamine neurons, the trafficking itinerary and fate of internalized DAT has not been elucidated. By monitoring surface-labeled DAT in transfected dopamine neurons from embryonic rat mesencephalic cultures, we find distinct sorting and fates of internalized DAT after amphetamine or PMA treatment. Although both drugs promote DAT internalization above constitutive endocytosis in dopamine neurons, PMA induces ubiquitination of DAT and leads to accumulation of DAT on LAMP1-positive endosomes. In contrast, after amphetamine exposure DAT is sorted to recycling endosomes positive for Rab11 and the transferrin receptor. Furthermore, quantitative assessment of DAT recycling using an antibody-feeding assay reveals that significantly less DAT returns to the surface of dopamine neurons after internalization by PMA, compared with vehicle or amphetamine treatment. These results demonstrate that, in neurons, the DAT is sorted differentially to recycling and degradative pathways after psychostimulant exposure or PKC activation, which may allow for either the transient or sustained inhibition of DAT during dopamine neurotransmission.—Hong, W. C., Amara, S. G. Differential targeting of the dopamine transporter to recycling or degradative pathways during amphetamine- or PKC-regulated endocytosis in dopamine neurons.

Keywords: ubiquitination, internalization, endosome sorting, fluorescence imaging

Amphetamines, a class of psychostimulants that structurally resemble the biogenic amine neurotransmitters dopamine (DA), norepinephrine, and serotonin, are thought to act mainly on the plasmalemmal and vesicular transporters for these neurotransmitters. d-amphetamine (AMPH) competitively inhibits the plasmalemmal transporters, including the DA transporter (DAT), which results in elevated synaptic monoamine concentrations and prolonged neurotransmission. AMPH also enters the neuronal cytoplasm through DAT, where it appears to facilitate reverse transport of DA from synaptic vesicles and enhance DA efflux through the DAT (1, 2).

DAT provides a gateway for AMPH to enter DA neurons. AMPH is reported to regulate the surface expression of DAT. Early studies show that [3H]DA uptake in rat striatal synaptosomes is decreased after systemic administration of methamphetamine to animals (3). In transfected cells, AMPH rapidly reduces the amount of cell surface DAT, leading to accumulation of DAT in intracellular endosomes (4–6). Recent reports have shown that AMPH initially induces a very brief, transient increase of DAT on the plasmalemmal membrane in rat striatal synaptosomes and transfected N2A neuroblastoma cells (7, 8). Cell surface DAT is also down-regulated after protein kinase C (PKC) activation by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) in Xenopus oocytes (9) and transfected cells (10, 11). Recent studies have identified critical residues in the C terminus of DAT necessary for PMA's action (12) and have shown that PMA activation of PKC leads to ubiquitination of DAT at its N terminus (13).

While most studies have focused on down-regulation of DAT by AMPH or PKC activation in heterologous expression systems, their effects on the trafficking of DAT and the fate of internalized DAT in DA neurons have not been fully characterized. Because the dynamic balance between endocytosis and recycling determines the amount of DAT on the neuronal surface and thus modulates DA neurotransmission, it is crucial to understand how AMPH or PKC activation regulates the density of DAT on the neuronal surface. In this study, we examine the trafficking itinerary and fate of internalized DAT following AMPH exposure or PKC activation in cultured DA neurons, and demonstrate that DAT internalized after PKC activation is destined for degradation, whereas DAT internalized with AMPH treatment undergoes recycling and returns to neuronal surface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals, radioligands, and antibodies

AMPH hemisulfate (A-5880, lot 074K1169), cocaine hydrochloride, and α-bungarotoxin-tetramethylrhodamine (Btx-TMR) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); PMA and bisindolylmaleimide (BIM) were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA); sulfo-NHS-biotin, sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin, and NeutrAvidin beads were from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA); transferrin-Alexa488 (Tf-488) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA); [3H]DA was from Perkin-Elmer (Waltham, MA, USA); FGF20, bFGF, and GDNF were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Sources of antibodies: hemagglutinin (HA; HA11), Covance (Berkeley, CA, USA); early endosome antigen 1 (EEA-1), BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA); ubiquitin (P4D1), Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); tyrosine hydroxylase (TH; TH152), Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA); TH (TH16), Sigma-Aldrich; LAMP1 (H4A3) and tubulin (6G7), Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA); DAT (MAB369), Chemicon (Temecula, CA, USA); polyclonal antisera raised against DAT, see ref. 14. Secondary antibodies (unlabeled, fluorophore-conjugated, or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated) were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA) or Invitrogen.

DNA constructs and cell lines

The HPGDSSGDSS sequence in the second extracellular loop of human DAT was replaced by YPYDVPDASL (HA epitope) or AAWRYYESSLEPYPDSSTS [bungarotoxin-binding site (BBS), underscored] to make DAT-HA or DAT-BBS, respectively. MEQKLISEEDLNGGGGGSTRA (Myc epitope, underscored, plus linker) was inserted before the start codon of DAT to generate Myc-DAT. Constructs were subcloned into pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen) using KpnI/XbaI, or into pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) between EcoRI/SalI or EcoRI/XbaI. The following plasmids were kind gifts: wild-type or dominant-negative human Rab5 and Rab11 (Rab11a isoform) in pEGFP-C1, Yong-Jian Liu (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA); transferrin-GFP, Gary Banker (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA); LAMP1-RFP (Addgene 1817; Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA), Walther Mothes (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA); pLenti-Synapsin-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP-WPRE (Addgene 20945), Karl Deisseroth (Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA). Lentiviruses were made by replacing hChR2(H134R)-EYFP with DAT-HA or DAT-BBS using AgeI/EcoRI sites, and transfecting 293T cells together with packaging plasmids from Addgene. Virus-containing culture medium was used to transduce mesencephalic cultures. MN9D cells stably expressing human DAT (MN9D-DAT) were described previously (14). HEK-DAT cells were generated by transfecting HEK293 cells with linearized pcDNA3.1(+)-Myc-DAT plasmid and selecting G418-resistant clones.

Preparation of mesencephalic cultures from rat embryonic ventral midbrain

All animal-related protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. Adapted from a previous method (15), ventral midbrain tissues were dissected from embryonic day 14 (E14)–E18 embryos of Sprague-Dawley rats (Hilltop Lab, Scottdale, PA, USA), incubated for 5 min at 37°C with 0.25% trypsin and 2 mM EDTA, and gently triturated in HEPES-buffered DMEM (DMEM-HEPES) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2 mM cysteine. After centrifugation (200 g, 5 min), cells were resuspended in DMEM-HEPES with 10% FBS and 2% B-27 (Invitrogen) and seeded onto Matrigel (BD Biosciences)-coated glass coverslips (density: 0.1–0.2×106 cells/cm2). An equal volume of Neurobasal medium (21103, Invitrogen; supplemented with 2% B-27, 10 ng/ml FGF20, 10 ng/ml bFGF, 10 ng/ml GDNF, 1 mM glutamine, and 50 U/ml Pen/Strep) was then added to the seeding medium. At day in vitro 5 (DIV5), 5 μM cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside was added. Medium was then partially changed every 2–5 d using supplemented Neurobasal medium. Neurons were transfected during DIV10–DIV14 using a modified calcium phosphate method (16) with endotoxin-free plasmid DNA, and used for internalization or recycling assays 3–6 d later. Some cultures were transduced during DIV7–DIV14 with lentiviruses and assayed 7–10 d later.

[3H]DA uptake

Transfected cells in 96-well plates or mesencephalic cultures in 48-well plates were incubated with drugs in the culture medium at 37°C, washed thoroughly with phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 (PBSCM), and processed for [3H]DA uptake as described previously (14). Data were analyzed for nonlinear curve fitting using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) to derive Vmax and Km values based on Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

Surface biotinylation

As described previously (14), MN9D-DAT cells, HEK-DAT cells, or mesencephalic cultures in 6-well plates were incubated with drugs in the medium at 37°C, washed 3 times with cold PBSCM, and biotinylated at 4°C (cells: 1 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin or sulfo-NHS-biotin, 0.5 h; neurons: 2 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-biotin, 20 min), followed by quenching and washing. Biotinylated proteins were enriched with NeutrAvidin beads. DAT signals were detected using MAB369 and analyzed with ImageJ (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) to measure integrated density values, then adjusted by protein concentrations in cell lysates (BCA kit; Pierce), and normalized to percentage of vehicle.

DAT ubiquitination assays

Following methods in Sorkina et al. (17), confluent HEK-DAT cells in 10-cm dishes or mesencephalic cultures in 6-well plates were treated with drugs, washed with PBSCM, and lysed. DAT in lysates was immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal anti-DAT and protein A/G agarose beads, immunoblotted with either anti-ubiquitin or MAB369.

DAT degradation assays

Confluent HEK-DAT cells in 24-well plates were first incubated with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide for 6 h, then with protein degradation inhibitors (if indicated) for 1 h. PMA or AMPH was then added into the medium and incubated for 1, 2, or 4 h, followed by cell lysis and immunoblotting with MAB369.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

HEK-DAT cells on glass coverslips were incubated with drugs in the medium, washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 2 min. Cells were then incubated (room temperature, 1 h) with DAT369 (1:500 dilution), anti-EEA1 (1:100), or anti-LAMP1 (1:100) in PBS (+2% BSA, 3% normal horse serum), washed, and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:300, room temperature, 1 h), washed, and mounted onto slides with Prolong antifade reagents (Invitrogen). Transient transfection was done using FuGene6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) 2–3 d before assays.

To label cell surface DAT-BBS and transferrin receptor (TfR), transfected cells were washed with HEPES-DMEM (serum-free, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.2, HEPES-buffered), and incubated with HEPES-DMEM containing 5 μg/ml Btx-TMR and 10 μg/ml Tf-488 (4°C, 0.5 h). Coverslips were then washed and returned to 37°C culture medium for internalization. Transfected neurons were preincubated with 20 μM tubocurarine for 15 min to block α7 nicotinic receptors, then incubated with 20 μg/ml Btx-TMR (20 min, 18°C). Cell surface DAT-HA was labeled by incubating with HA11 in the medium at 18°C for 30 min (transfected cells: 2 or 5 μg/ml HA11; transfected neurons: 20 μg/ml HA11), followed by internalization or recycling assays at 37°C.

Images were taken using an Olympus FluoView FV1000 laser scanning confocal system (×60 oil-immersion objective, PLAPO, NA 1.40, pinhole 1 Airy unit; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Signals in 3 channels (excitation wavelengths: 488/543/633 nm; emission: 510/572/664 nm) were acquired using sequential frame mode and Kalman integration (1024×1024 pixel resolution, 8 μs/pixel scanning speed). For quantitative fluorescence microscopy, signals from the top to bottom of cells (typically 10 μm) were acquired in Z stacks (0.5- or 1-μm intervals, 512 × 512 pixel in XY dimensions, 4 μs/pixel). Optimal acquisition setting was determined by adjusting laser intensity and photomultiplier tube voltage/gain to ensure that the fluorescent intensities stayed within the linear range of detection. Same parameters were set for all images in one experiment. Four-channel Z-stack signals (excitation: 405/488/561/640 nm; emission: 450/525/595/700 nm) were taken with a Nikon A1 system (VC ×60 oil-immersion objective, PLAN APO, NA 1.4; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using sequential line-scanning mode and Kalman integration (512×512 pixel resolution, 0.5 frame/s speed) (see Fig. 6D). Data were saved in FluoView or Nikon raw tiff format, and imported into ImageJ for analysis. Regions of interest (ROIs) were defined using the GFP channel for cells transfected with GFP-DAT-HA, or TH staining for transfected DA neurons. After subtracting background (average from 3 regions without transfected cells), mean fluorescence intensities in ROIs from Z stacks were used for quantification. For colocalization analysis, confocal images were imported into Imaris (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland). Threshold values of fluorescence signals above background in each channel were analyzed with the Surpass module, and input into the Coloc module to calculate the percentage of DAT voxels colocalized with other markers out of the total DAT voxels above threshold.

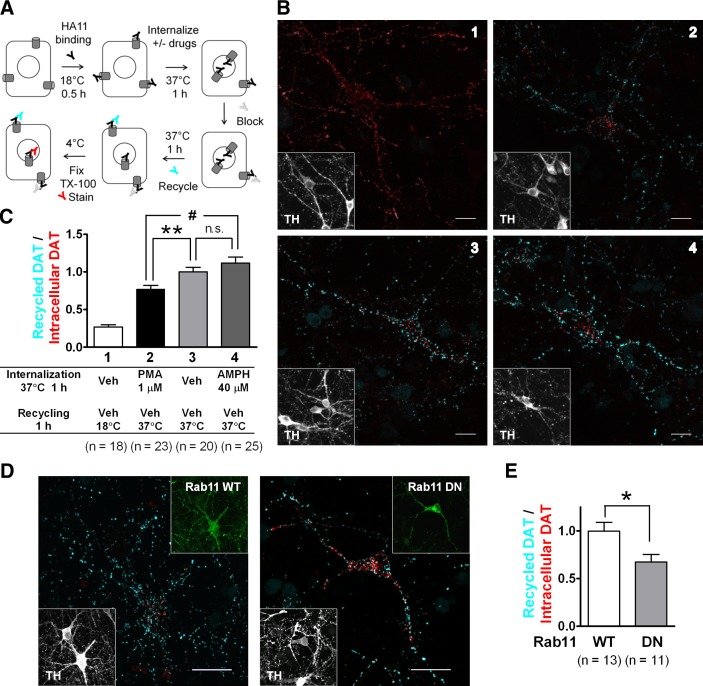

Figure 6.

After AMPH-induced down-regulation, internalized DAT recycles to the neuronal surface. A) Schematic of recycling assays. B) Representative confocal Z-stack projection images from transfected DA neurons. Images 1–4 correspond to groups 1–4 in panel C. Scale bars =10 μm. Inset: TH staining. Only transfected neurons show specific signals of recycled DAT and intracellular DAT. C) Quantitation of DAT recycling. Ratios of recycled/intracellular DAT signals in confocal stacks were normalized to the average value in group 3 (mean±sem, n=number of DA neurons). n.s., not significant. **P < 0.01, #P < 0.001; 2-sided t test. D) Representative Z-stack projection images from DA neurons overexpressing GFP-Rab11 WT or DN. Neurons were treated with 40 μM AMPH for 1 h to induce DAT internalization, followed by 1 h recycling. Scale bars = 10 μm. Top insets: Rab11WT or DN. Bottom insets: TH staining. E) Overexpression of Rab11 DN inhibits DAT recycling after AMPH-induced DAT internalization. Ratios of recycled/intercellular DAT were quantified and normalized to the average value in Rab11 WT group (means±sem, n=number of DA neurons). *P < 0.05; 2-sided t test.

Internalization assays in neurons using antibody-feeding methods

Transfected neurons on coverslips were incubated with 20 μg/ml HA11 in culture medium for 0.5 h at 18°C, washed with DMEM-HEPES, and incubated in medium containing vehicle, AMPH, or PMA at 37°C for 1 h. Neurons were then washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (20 min, room temperature). To label cell surface HA11 signals, coverslips were incubated with 80 μg/ml goat anti-mouse IgG (GAM)-DyLight649 (GAM-649; 0.5 h, room temperature) in PBS staining solution (PBS with 1% normal goat serum and 1% BSA). Neurons were washed, refixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (on ice; 15 min). Neurons were then incubated with TH152 (1:500 dilution, 1 h, room temperature), washed, incubated with 2 μg/ml GAM-549 and 1 μg/ml goat anti-rabbit IgG-DyLight488 (GAR-488) for 1 h at room temperature, washed, and mounted onto slides. (See schematics in Fig. 4G.).

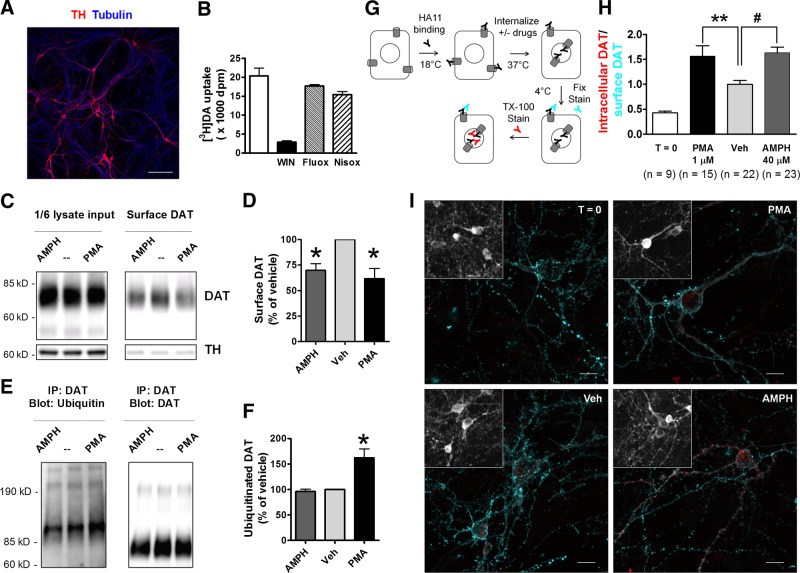

Figure 4.

Amphetamine promotes DAT internalization in DA neurons. A) Representative image of DA neuron-enriched rat embryonic mesencephalic cultures, stained with anti-TH and anti-tubulin. Scale bar = 100 μm. B) Robust [3H]DA uptake was blocked by 2 μM WIN35428 (WIN), a DAT inhibitor, but not by 100 nM fluoxetine (Fluox) or 100 nM nisoxetine (Nisox), inhibitors of the serotonin or norepinephrine transporter, respectively. Representative results from DIV29 cultures in 48-well plates (means±sd, triplicate wells, 50 nM [3H]DA+950 nM DA, 5 min uptake), n = 3 assays. C, D) AMPH or PMA reduces DAT density on the neuronal surface. Mesencephalic cultures transduced with lentivirus LV-Syn-DAT-BBS were treated with vehicle, 40 μM AMPH, or 1 μM PMA for 1 h, followed by surface biotinylation. C) Representative blots. The very low signal for TH (an intracellular protein) in biotinylated fractions validates the quality of biotinylation assays. D) Quantitated results (means±sem, n=3 experiments). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle (Veh); 2-sided t test. E, F) PMA, but not AMPH, induces ubiquitination of DAT in mesencephalic cultures transduced with LV-Syn-DAT-HA. After 1 h drug treatment, cultures were lysed and immunoprecipitated with polyclonal anti-DAT, then blotted with antiubiquitin or MAB369. E) Representative blots. F) Quantitated results (means±sem, n=3 experiments). *P < 0.05 vs. Veh; 2-sided t test. G) Schematic of internalization assays. See details in Materials and Methods. H) Quantitation of DAT internalization. Ratios of intracellular to surface HA signal intensities from confocal stacks were measured and normalized to the average in Veh group (means±sem, n=number of DA neurons). **P < 0.01, #P < 0.001; 2-sided t test. I) Representative confocal Z-stack projection images of transfected DA neurons: no internalization (T=0), after 1 h internalization in the presence of vehicle, 40 μM AMPH, or 1 μM PMA. Scale bars: 10 μm. Inset: TH staining. Specific signals of surface and intracellular DAT-HA are only seen in transfected neurons.

Recycling assays in neurons

After the HA11 labeling and internalization, neurons were washed with DMEM-HEPES and incubated with 100 μg/ml GAM in culture medium (20 min, 18°C) to block residual HA11 on the neuronal surface. Coverslips were then thoroughly washed and incubated in drug-free culture medium containing 10 μg/ml GAM-649 at 37°C for 1 h, to detect HA11-bound DAT-HA recycling from endosomes to the plasma membrane. Neurons were then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with TH152, followed by staining with 1 μg/ml GAM-549 and 1 μg/ml GAR-488. (See schematics in Fig. 6A.).

RESULTS

Down-regulation of cell surface DAT by AMPH and PMA in transfected cells

We initially examined the effects of AMPH on DAT trafficking in transfected cells using surface biotinylation and [3H]DA uptake assays. In HEK-DAT cells, cell surface DAT was reduced in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1A), with 73 ± 3% (n=3) remaining after 20 min incubation of 40 μM AMPH. Cell-surface DAT was also decreased by AMPH in MN9D-DAT cells (an embryonic mouse midbrain-neuroblastoma hybrid stably transfected with DAT), with a corresponding decrease in the Vmax for [3H]DA uptake activity (60±8% of control; mean±sem, n=3; Supplemental Fig. S1). These studies indicate that AMPH decreases surface DAT in both neuronally derived and non-neuronal cell lines.

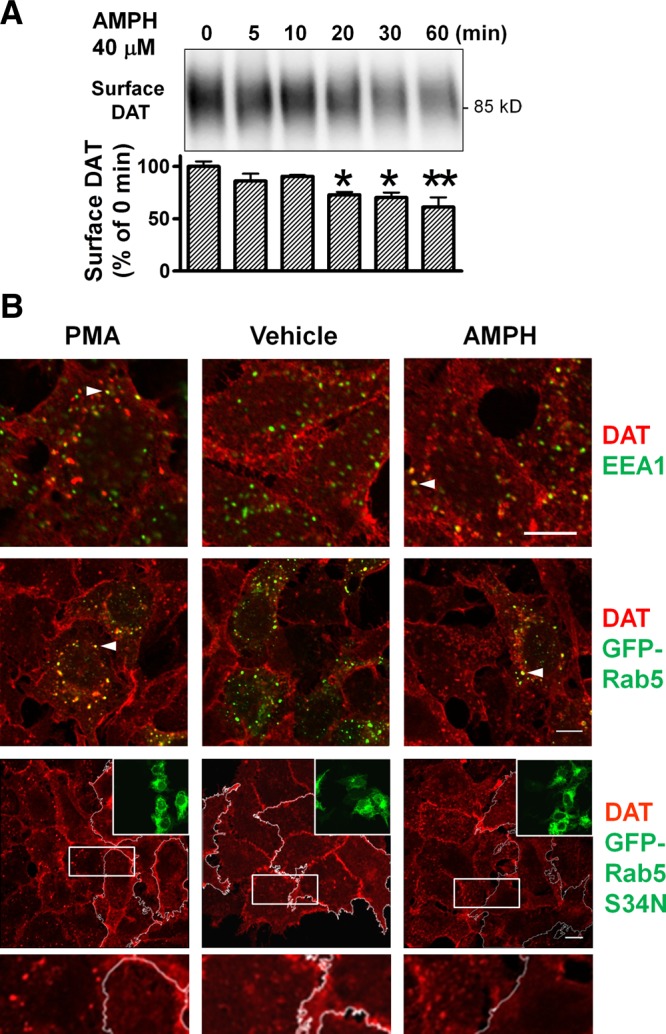

Figure 1.

AMPH and PMA-induced internalization of DAT in transfected cells. A) Cell surface DAT is decreased following exposure to 40 μM AMPH in a time-dependent manner in HEK-DAT cells. Representative blot from n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. T = 0; 2-sided t test. B) DAT is internalized and transits through EEA1- or Rab5-positive vesicles in HEK-DAT cells after 20 min drug treatment at 37°C. Colocalization of intracellular DAT puncta with EEA1 (1 μM PMA, 4 μM AMPH) and GFP-Rab5 (2 μM PMA, 20 μM AMPH). Arrowheads denote colocalized pixels. Internalization of DAT was blocked by overexpression of GFP-Rab5 S34N (transfected cells traced with white lines). Boxed areas are enlarged at bottom. PMA: 1 μM; AMPH: 20 μM. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Experiments using fluorescence microscopy to colocalize DAT with endosomal markers confirmed that DAT internalization accounts for the decrease in DAT protein at the cell surface. Brief incubations (20 min to 1 h) with AMPH or the PKC-activator PMA induced more DAT-positive intracellular puncta in HEK-DAT cells, compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 1B), with a predominant presence on vesicles positive for EEA1, consistent with results from a previous imaging study in a different cell line (5). As EEA1 is an effector of Rab5, a small Ras-like GTPase associated with early endosomes, we transfected cells with GFP-tagged Rab5 and observed substantial colocalization of intracellular DAT staining with GFP-Rab5. Overexpression of the dominant-negative Rab5 mutant S34N resulted in fewer DAT-positive puncta in cells after AMPH or PMA treatment. These data suggest that after either AMPH or PMA treatment, DAT undergoes internalization and transits through early endosomes containing EEA1 and Rab5.

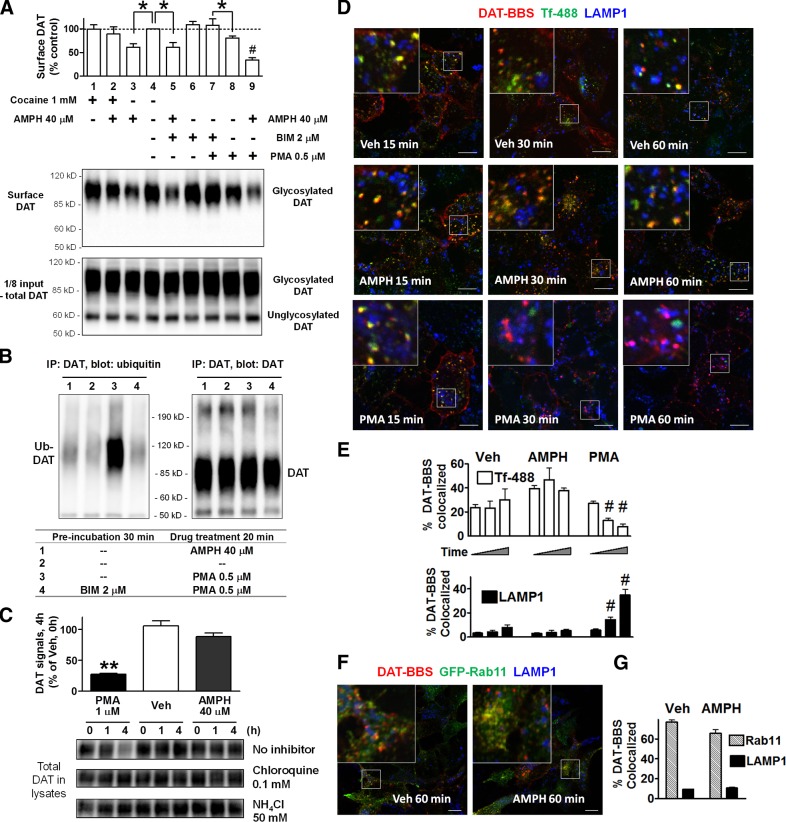

Unlike PMA, AMPH does not trigger ubiquitination and degradation of DAT

We then examined whether AMPH- or PMA-induced down-regulation of DAT involves different mechanisms. In HEK-DAT cells, preexposure to 1 mM cocaine, a DAT blocker, abolished AMPH's effects (89±15 vs. 61±7%, n=3; Fig. 2A, lanes 2 vs. 3), suggesting that AMPH needed to be transported by DAT into the cytoplasm to exert its effects. Preincubation with BIM, a PKC inhibitor, blocked PMA's effects to reduce cell surface DAT (108±13 vs. 80±5%; Fig. 2A, lanes 7 vs. 8), but it did not reverse AMPH's effect (61±10%; Fig. 2A, lane 5). Furthermore, coapplication of AMPH and PMA resulted in further reduction of cell surface DAT (34±5%; Fig. 2A, lane 9) than either drug alone. These additive effects of AMPH and PMA suggest that the two compounds act through different mechanisms to induce DAT down-regulation.

Figure 2.

In contrast to PMA treatment, AMPH application does not induce ubiquitination and degradation of DAT. A) AMPH-induced down-regulation of DAT is inhibited by cocaine, a DAT blocker, but not by the PKC inhibitor BIM. HEK-DAT cells were pretreated with cocaine or BIM for 30 min, then incubated with AMPH or PMA for 20 min. Mature DAT on the cell surface is glycosylated and shown as diffuse bands in immunoblots. Summarized results of surface DAT signals (normalized to control in lane 4, means±sem, n=3 experiments) with representative blots. *P < 0.05, #P < 0.001; 1-way ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni test. B) AMPH does not induce ubiquitination of DAT. DAT from drug-treated HEK-DAT cells was immunoprecipitated and blotted for ubiquitin. Note the reduced electrophoretic mobility of ubiquitinated DAT (Ub-DAT). Equal amounts of immunoprecipitated DAT were verified by DAT antibodies. C) AMPH does not cause degradation of DAT. PMA-induced loss of DAT signals was prevented by chloroquine or NH4Cl. Representative blot and summarized graph from n = 3 experiments. D) Representative images showing that internalized DAT-BBS during AMPH incubation colocalizes with markers for recycling endosomes, but not with LAMP1, a maker for late endosomes/lysosomes. Cells were labeled with Btx-TMR and Tf-488, and incubated for 15, 30, or 60 min at 37°C in the presence of vehicle (Veh), 40 μM AMPH, or 1 μM PMA. Scale bars = 10 μm. E) Quantitation of DAT-BBS colocalization with Tf-488 or LAMP1. #P < 0.001 vs. AMPH-treated cells; 1-way ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni test. F, G) Colocalization of internalized DAT-BBS with GFP-Rab11. Representative images and colocalization quantification. Scale bars = μm. Values are means ± sem from 3–5 images at each time point (E, G); total cells >20.

DAT has been shown previously to be ubiquitinated following PMA treatment in transfected HeLa cells (17). We treated HEK-DAT cells with PMA or AMPH, enriched DAT by immunoprecipitation, and examined DAT ubiquitination with ubiquitin antibodies. PMA caused a dramatic increase of DAT-ubiquitin conjugates, which was blocked by the PKC inhibitor BIM, whereas AMPH induced little or no ubiquitination of DAT (Fig. 2B). Our group has previously shown that after PMA treatment, DAT internalizes and traffics to late endosomes/lysosomes for degradation in transfected MDCK cells (10). To determine whether AMPH could cause degradation of DAT, we performed similar assays in HEK-DAT cells. Consistent with previous data, PMA decreased DAT expression markedly (27±2% of vehicle after 4 h, n=3 experiments), and this effect was blocked by preincubation with lysosomotropic agents (0.1 mM chloroquine or 50 mM NH4Cl). However, no significant reduction of DAT proteins was seen (89±6% of vehicle; Fig. 2C) in AMPH-treated cells, which suggests that under basal or AMPH-stimulated conditions the majority of internalized DAT is not destined for lysosomal degradation.

To monitor the trafficking itinerary of the DAT, we constructed a DAT with a BBS in an extracellular loop (DAT-BBS), and confirmed its capacity for robust [3H]DA transport activity (Supplemental Fig. S2). Since the HEK-DAT cell line is a good model to characterize drug-induced down-regulation of DAT, we transiently transfected DAT-BBS into these cells and labeled cell surface DAT-BBS with Btx-TMR at 4°C. Tf-488 was used to label the TfR, a well-established marker of recycling pathways. Cells were then transferred to 37°C to allow internalization, followed by fixation and immunostaining for LAMP1, a marker for late endosomes/lysosomes. With either vehicle or AMPH treatment, DAT-BBS signals exhibited substantial colocalization with Tf-488, but not with LAMP1 (Fig. 2D, E). However, in PMA-treated cells, DAT-BBS signals colocalized with LAMP1 significantly at longer durations (30, 60 min after treatment). Furthermore, endocytosed DAT-BBS after vehicle or AMPH treatment also colocalized with GFP-Rab11, a marker for recycling endosomes (Fig. 2F, G). Thus, DAT transits to recycling endosomes during constitutive endocytosis or AMPH-induced internalization but is targeted to late endosomes/lysosomes for degradation after PMA treatment.

DAT internalized after AMPH treatment is recycled to the cell surface

The internalization and recycling of DAT was examined with quantitative immunofluorescence techniques using an antibody-feeding method that has been used previously to study recycling of glucose transporters (18). An engineered DAT with an extracellular HA epitope (DAT-HA) as originally reported by Sorkina et al. (17) retains robust transport (Supplemental Fig. S2). We transfected HEK293 cells with GFP-DAT-HA (N-terminal GFP-tagged DAT-HA), labeled cells with the HA11 antibody, and incubated them in drug-containing medium at 37°C during the internalization step. Cell surface HA11-bound GFP-DAT-HA was first stained with GAM-649, before cells were permeabilized and stained with GAM-549 to reveal internalized GFP-DAT-HA bound with HA11. By measuring ratios of intracellular to surface HA epitopes, we observed a time-dependent increase of GFP-DAT-HA internalization, with significantly higher rates in AMPH or PMA-treated cells than during basal endocytosis (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Recycling of DAT in transfected cells after internalization induced by AMPH, but not by PMA. A) Time course of GFP-DAT-HA internalization with representative images. Cell surface GFP-DAT-HA was labeled by HA11, followed by internalization in the presence of drugs. Dashed line denotes background signals from cells labeled by HA11, but kept on ice without internalization. #P < 0.001 vs. vehicle; 2-way ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni test. B) Time course of GFP-DAT-HA recycling with representative images. After HA11 labeling and 1 h internalization, drugs were washed out, and the remaining HA11 on the cell surface was blocked. Cells were then returned to 37°C medium containing GAM-649 to allow recycling. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle; 2-way ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni test. C) Validation of recycling signals by no-recycling control and monensin-treated groups. Monensin (50 μM) significantly inhibited recycling of GFP-DAT-HA. *P < 0.05; 2 -sided t test. A–C) Points represent means ± sem from ≥4 confocal stacks, containing n > 20 cells. Images show single sections from Z stacks. Scale bars = 10 μm. D) Recovery of [3H]DA uptake activity after AMPH treatment. HEK-DAT cells were treated with vehicle, 40 μM AMPH, or 1 μM PMA for 0.5 h, then washed thoroughly and incubated with drug-free medium for recovery. Values are means ± sem from n = 3 assays. #P < 0.001 vs. AMPH-treated cells; 2-sided t test. E) Representative [3H]DA uptake curves after 1 h recovery. Values are means ± sd from triplicates.

The recycling of internalized GFP-DAT-HA after drug treatment was measured directly. After HA11 labeling and internalization, drugs were washed out, and cell surface GFP-DAT-HA bound with HA11 was blocked by a saturating concentration (100 μg/ml) of unlabeled GAM. Cells were then returned to 37°C for various times, during which intracellular HA11-bound GFP-DAT-HA could be recycled to the cell surface and detected by GAM-649 (10 μg/ml) included in the medium. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and stained for intracellular HA11-bound GFP-DAT-HA with GAM-549 (1 μg/ml). We quantified the ratio of recycled DAT over intracellular DAT fluorescent intensities from confocal Z stacks, and observed DAT internalized during AMPH treatment had a recycling rate similar to those of vehicle treatment (Fig. 3B). In contrast, a significantly lower ratio was seen in cells treated with PMA during internalization.

To confirm that the GAM-649 signals resulted from recycled GFP-DAT-HA, we performed several control experiments. First, the high-affinity binding of HA11 to DAT-HA in labeled cells was maintained through washes with high-salt acidic stripping buffer (0.5 M NaCl and 0.5% acetic acid, pH 3), suggesting that HA11 was unlikely to dissociate from DAT-HA in acidic endosomes (pH 4–5). Second, we included a no-recycling group, in which cells underwent internalization and blocking steps, but were incubated with GAM-649-containing medium at 18°C during recycling, a temperature that allows antibody binding but blocks membrane trafficking. The very low signals observed in this control experiment (Fig. 3C) confirmed that nearly all HA11-bound GFP-DAT-HA remaining on the cell surface was saturated by blocking and that the nonspecific binding of GAM-649 to cells was very low. Third, we treated cells with 50 μM monensin during the blocking and recycling steps. Monensin, an Na+/H+ ionophore that prevents acidification of endosomes, partially inhibits the constitutive recycling of membrane proteins such as the macrophage Fc receptors (19). It was also recently reported to cause intracellular DAT accumulation by interfering with DAT recycling (20). Our results showed that the ratios of recycled/intracellular DAT in monensin-treated cells are significantly less than those in corresponding groups without monensin treatment, which suggests that the assay does detect recycling rather than spurious secondary antibody unbinding and rebinding during the recycling steps (Fig. 3C). Both with and without monensin, a significantly lower recycled-to-intracellular DAT ratio is observed following PMA-treatment (with monensin, 0.47±0.02 for PMA-treated vs. 0.71±0.06 for vehicle-treated samples; without monensin, 0.73±0.07 for PMA-treated vs. 0.97±0.11 for vehicle-treated samples), consistent with time course shown in Fig. 3B.

Next we examined the recycling of DAT by measuring the recovery of DA uptake as internalized DAT returning to the cell surface. After AMPH or PMA treatment, cells were washed and incubated with drug-free medium to allow recycling of DAT. In AMPH-treated cells, DA uptake activities appeared to gradually recover. In contrast, in PMA-treated cells, DA uptake remained significantly reduced after 2 h (Fig. 3D, E). Together with results from DAT degradation and colocalization assays in Fig. 2, these results demonstrate that in transfected cells, DAT internalized following AMPH exposure proceeds through a recycling pathway, whereas DAT internalized by PKC activation traffics to lysosomes for degradation.

AMPH promotes DAT internalization in DA neurons

To overcome the challenges of studying DAT trafficking directly in DA neurons, we prepared high-density dopaminergic cultures from embryonic rat mesencephalon. These cultures showed abundant TH staining (Fig. 4A) and robust [3H]DA uptake, which was sensitive to the DAT blocker WIN35428, but not to inhibitors of the norepinephrine transporter (nisoxetine) or serotonin transporter (fluoxetine) (Fig. 4B). We estimated that ∼20% of the neurons were DA neurons (TH staining/total neurons in 2 representative batches: 27/196 and 87/398).

To facilitate the examination of DAT down-regulation or ubiquitination in these cultures, we transduced neurons with lentiviruses, LV-Syn-DAT-HA or LV-Syn-DAT-BBS, that enable expression of DAT-HA or DAT-BBS driven by the synapsin promoter. Our assessment showed that >50% of neurons were transduced (Supplemental Fig. S3A), and total DAT activity was increased ∼2-fold in [3H]DA uptake assays (Supplemental Fig. S3B). In surface biotinylation assays, either AMPH or PMA significantly reduced the density of DAT on neuronal surface in cultures transduced by LV-Syn-DAT-BBS (Fig. 4C, D). PMA, but not AMPH, significantly increased DAT ubiquitination in cultures infected with LV-Syn-DAT-HA (Fig. 4E, F). These results were consistent with those in HEK-DAT cells (Fig. 2A, B), albeit viral-induced DAT expression was not limited to DA neurons in these assays.

To examine drug-induced DAT internalization in identified DA neurons, we transfected mesencephalic cultures with DAT-HA using the calcium phosphate method, and performed internalization assays (Fig. 4G) as in transfected cells. Fluorescence signals from intracellular and surface DAT-HA were quantified from confocal Z stacks of DA neurons post hoc stained for TH. Consistent with prior results, we observed significantly higher intracellular/surface HA ratios in AMPH or PMA-treated neurons, demonstrating that AMPH or PMA increased DAT internalization rates in DA neurons (Fig. 4H, I).

In DA neurons, DAT internalized by AMPH colocalizes first with markers of early endosomes and then with recycling endosomes

To monitor the trafficking itinerary of DAT in DA neurons, we cotransfected mesencephalic cultures with DAT-BBS and GFP-Rab5 or GFP-Rab11. DAT-BBS on the neuronal surface was labeled by Btx-TMR at 18°C, then neurons were transferred to 37°C cultured medium with vehicle or AMPH to initiate internalization of DAT-BBS. Fluorescence signals of Btx-TMR bound to DAT-BBS colocalized initially (15 min) with GFP-Rab5 (Fig. 5A) and later (30 min) with GFP-Rab11 (Fig. 5B), markers for early endosomes and recycling endosomes, respectively.

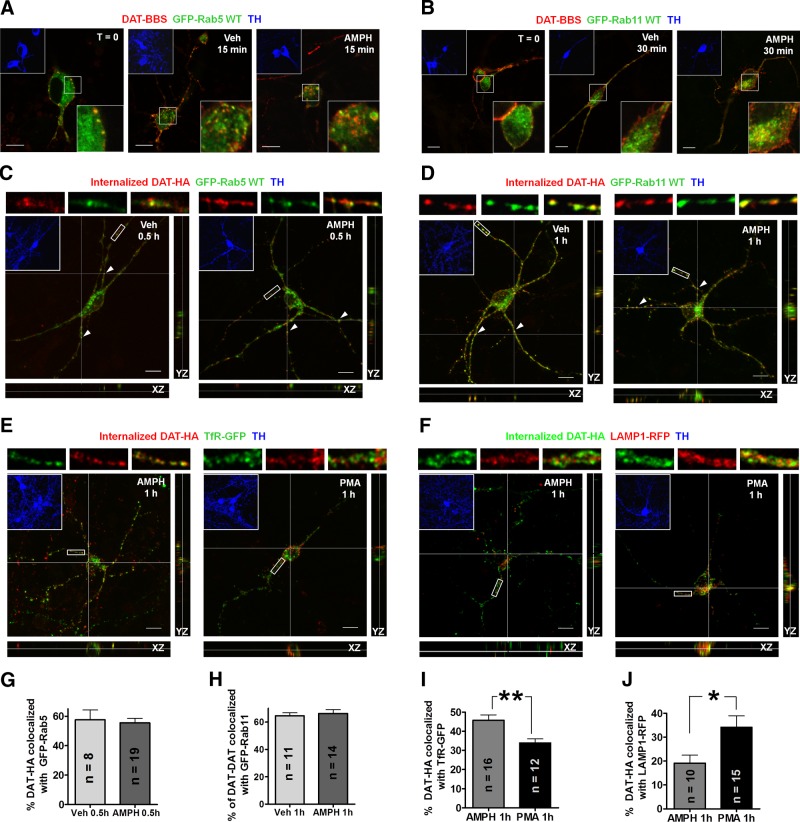

Figure 5.

In DA neurons, the DAT internalized after AMPH exposure transits through recycling endosomes, whereas after PKC activation, the internalized DAT is sorted to late endosomes/lysosomes. A, B) Colocalization of internalized DAT-BBS with GFP-Rab5 (A) or GFP-Rab11 (B). Transfected neurons were labeled with Btx-TMR and incubated at 37°C in the presence of vehicle (Veh) or 40 μM AMPH for 15 min (A) or 30 min (B). Representative confocal sections. Top insets: TH staining. Bottom insets: boxed area enlarged. Scale bars = 10 μm. C, D) After constitutive or AMPH-triggered internalization, DAT-HA colocalizes with intracellular vesicles that are GFP-Rab5-positive (C) or GFP-Rab11-positive (D). E, F) After 40 μM AMPH treatment, internalized DAT colocalizes more significantly with TfR-GFP (E); in contrast, internalized DAT after 1 μM PMA treatment colocalizes more with LAMP1-RFP (F). C–F) HA11-bound DAT-HA on the neuronal surface after internalization was saturated by unlabeled GAM, then intracellular DAT-HA was stained. Representative confocal stacks showing XY projections. Arrowheads denote colocalized voxels shown in YZ and XZ sections at the cross lines. Top panels are enlarged images of the boxed areas from single sections. Insets: TH staining. Scale bars = 10 μm. G–J) Summary of the quantitative colocalization data for panels C (G), D (H), E (I), F (J). Values are means ± sem, n = number of DA neurons. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; 2-sided t test.

For quantitative colocalization analysis, we cotransfected DA neurons with DAT-HA and endosomal markers and modified the antibody-feeding method to detect only internalized DAT. After HA11 labeling and internalization, neurons were fixed with paraformaldehyde, incubated with 100 μg/ml GAM to saturate HA11 signals remaining on the surface, then refixed, permeabilized, and stained with 1 μg/ml fluorophore-conjugated GAM to reveal internalized DAT-HA bound with HA11. Using GFP-Rab5 and GFP-Rab11 as markers of early and recycling endosomes, we found that the majority of DAT-HA voxels in confocal Z stacks colocalized with GFP-Rab5 following 0.5 h internalization in the presence of vehicle (58±7%) or 40 μM AMPH (55±3%) (Fig. 5C, G), and colocalized with GFP-Rab11 following 1 h internalization in the presence of vehicle (65±2%) or 40 μM AMPH (67±3%) (Fig. 5D, H). Next we compared the distribution of internalized DAT after AMPH or PMA treatment, by cotransfecting neurons with TfR-GFP or LAMP1-RFP, markers for recycling endosomes or late endosomes/lysosomes, respectively. Following 1 h AMPH treatment, internalized DAT colocalized significantly more with TfR-GFP (46±3 vs. 34±2% in PMA group; Fig. 5E, I) but significantly less with LAMP1-RFP (19±3 vs. 34±5%; Fig. 5F, J). These data support the notion that internalized DAT following AMPH exposure traffics to early endosomes and then to recycling endosomes.

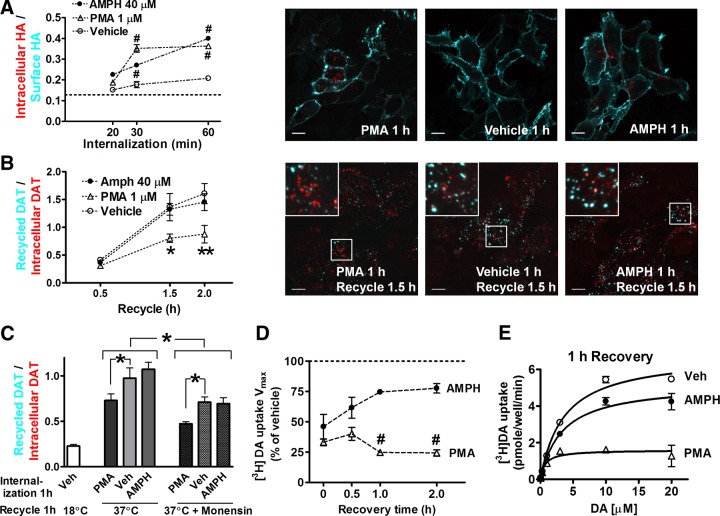

DAT recycles to neuronal surface after AMPH-induced internalization

We next used recycling assays to examine whether internalized DAT in DA neurons is recycled to the surface (Fig. 6A) as in transfected cells (Fig. 3B). In cultures transfected with DAT-HA, DA neurons were identified by TH staining, and fluorescence signals of recycled and intracellular DAT-HA were recorded in confocal Z stacks and quantified. Our results showed that in DA neurons, recycling rates of DAT (measured by recycled/intracellular DAT ratios) after constitutive or AMPH-induced DAT internalization (Fig. 6B, C) were similar. However, in PMA-treated neurons, a significantly lower ratio was evident, which suggests that after PKC-mediated internalization, a significantly greater portion of DAT-HA was retained intracellularly and did not return to the neuronal surface. In contrast, after either AMPH-mediated or constitutive endocytosis, internalized DAT-HA was likely recycled to the cell surface in DA neurons, consistent with the results in transfected HEK cells.

Because internalized DAT colocalized significantly with GFP-Rab11 (Fig. 4D), we next examined whether interfering with Rab11-mediated recycling mechanisms would impair the recycling of DAT. Neurons were cotransfected with DAT-HA and GFP-Rab11 WT or DN (S25N) and subjected to recycling assays following AMPH-induced DAT internalization. In DA neurons expressing GFP-Rab11 DN, the ratio of recycled/intracellular DAT was significantly lower than that in DA neurons expressing GFP-Rab11 WT (Fig. 6D, E), suggesting that Rab11 plays an important role in the recycling of DAT following AMPH-induced DAT down-regulation.

DISCUSSION

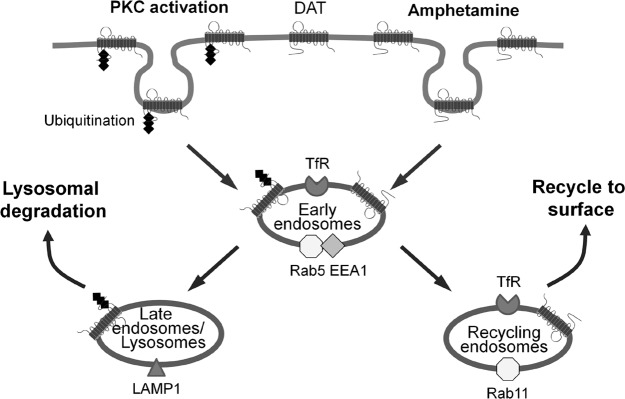

In this study, we identified distinct trafficking itineraries and fates of DAT following its internalization after AMPH treatment or PKC activation, in both cultured cells and DA neurons. Our data support the hypothesis that postendocytic sorting of DAT is regulated differentially by distinct stimuli. PKC activation triggers ubiquitination-dependent degradation of DAT, whereas the DAT internalized after AMPH treatment is sorted to recycling endosomes and destined for surface reinsertion (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Model for the differential postendocytic sorting of DAT that occurs after AMPH addition or PKC activation. DAT internalized through either mechanism initially transits through early endosomes but has a divergent fate in subsequent steps. PKC activation triggers ubiquitination-dependent degradation of DAT. In contrast, DAT internalized in response to AMPH traffics to Rab11-positive recycling endosomes and returns to the neuronal surface.

Differential postendocytic sorting of DAT may modulate DA neurotransmission

Because DAT clears synaptically released DA and thus terminates DA signaling, the density of DAT on DA neurons has a profound effect on the strength of DA neurotransmission. The dynamic balance between constitutive endocytosis and recycling determines the net amount of DAT on the neuronal surface under basal conditions. Because DA neurons receive various neurotransmitter and neuromodulatory inputs from other systems, the balance between internalization and recycling of DAT is likely regulated by different signaling pathways. PKC signaling can trigger internalization of DAT and directs the carrier to lysosomal degradation, thus decreasing the abundance of DAT on the neuronal surface, and stimulation of the corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 is known to activate PKC in DA neurons (21). In contrast, on entry into DA neurons, AMPH activates distinct signaling pathways and causes internalization of DAT proteins, which then traffic to recycling endosomes. Once the effects of AMPH wane, these DATs can be reinserted into the neuronal membrane. Since similar events involving activity-dependent alternative trafficking fates of synaptic AMPA receptors underlie long-term potentiation and long-term depression (22, 23), we propose that differential DAT sorting between recycling and degradative pathways provides a mechanism for the adaptive changes in DAT activity that occur during normal neurotransmission and after psychotimulant exposure.

The mechanism by which AMPH activates intracellular signaling to trigger endocytosis of DAT remains to be elucidated. A multitude of signaling pathways has been implicated in regulating DAT trafficking, including tyrosine kinases (24), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (25), mitogen-activated kinase (26), CaMKII (27), and Akt (27). PKC inhibitors have been reported to block AMPH-induced DA efflux via DAT (28). However, consistent with results in other transfected cell lines (29), in our hands PKC inhibitors did not block AMPH-induced DAT down-regulation (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, a high level of mitogen-activated kinase phosphatase 3 exists in MN9D cells, which inhibits PKC-induced internalization of DAT (30), but AMPH-induced DAT down-regulation is not blocked (Supplemental Fig. S1). Preliminary studies in our laboratory suggest that the mechanism of AMPH-dependent DAT internalization also requires the activation of small GTPases, such as RhoA (31). AMPH-mediated internalization of DAT was shown by others to be blocked by expression of a dominant-negative dynamin I, K44E (4). However, because dynamin is required for multiple endocytic mechanisms (32), the specific endocytic machineries involved in AMPH-mediated DAT internalization in DA neurons will also require further investigation. As recently studies show that partition of DAT in cholesterol-rich membrane domains affects PMA-induced DAT phosphorylation and endocytosis (33, 34), it is tempting to speculate that DAT in specific membrane domains is differentially regulated by AMPH or PMA, resulting in distinct trafficking itineraries and fates.

Recycling of internalized DAT in response to AMPH

This study presents the first direct evidence in DA neurons that DAT recycles to the neuronal surface after AMPH-induced endocytosis. Furthermore, we have shown that internalized DAT strongly colocalizes with GFP-Rab11 and TfR-GFP (Fig. 5B, D, E) and that a dominant-negative Rab11 mutant inhibits the recycling of DAT in DA neurons. Similar to recent work showing that a mutant Rab11 effector prevented AMPH-induced internalization of the norepinephrine transporter (35), our findings demonstrate a critical role of Rab11 in the trafficking of monoamine transporters. In our assays, internalized and recycled DATs are distributed on both the soma and neurites of DA neurons (Figs. 4I, 6B), suggesting that DAT trafficking on both somatodendritic regions and axonal nerve terminals can be dynamically regulated to alter dopaminergic signaling. Moreover, recycled DAT signals appear to have a more pronounced distribution along the neurites (Fig. 6B), consistent with recent immunostaining studies in postnatal rat DA neurons and in DAT-HA knock-in mice showing that axonal DAT is enriched in recycling endosomes and on the plasma membrane (36, 37). A recent study using differential centrifugation did not detect significant redistribution of DAT between striatal synaptosomal membrane and vesicle fractions after AMPH administration to rats, although [3H]DA uptake was decreased (38). The intriguing possibility that in vivo the trafficking of DAT on nerve terminals or somatodendritic regions may be differentially regulated requires further examination with high-sensitivity novel approaches in future studies.

We also observed significant colocalization of internalized DAT with GFP-Rab11 (Fig. 5B, D) and strong signals of recycled DAT in DA neurons (Fig. 6B) following constitutive endocytosis. Together with data from transfected cells (Fig. 2C, D), these results suggest that the majority of constitutively internalized DAT undergoes recycling, in agreement with observations that in DA neurons from DAT-HA knock-in mice constitutively internalized DAT localizes predominantly in early and recycling endosomes, with a small pool of DAT-HA present in lysosomes (37). Discrepancies with another recent report (39) may arise from differences in experimental strategies for monitoring DAT, such as the fusion of a Tac transmembrane domain to the DAT and the use of fluorescent cocaine analogs that may display changes in binding affinity as the transporter traffics through various acidic endosomal compartments.

Previously, the plasma membrane insertion rate of DAT during AMPH incubation was measured using surface biotinylation assays in transfected cells and found to be reduced (29, 40) or unchanged (41), compared with vehicle treatment. In our experiments, we examined the reinsertion of internalized DAT without drugs present and found that it has a similar rate of recycling following constitutive or AMPH-induced endocytosis (Figs. 3B and 6C). Although it is possible that AMPH also influences the reinsertion rate of recycled DAT, our results strongly suggest that AMPH has a predominant effect on DAT internalization (Fig. 3A).

We have used a number of different methods for tagging and monitoring the fate and recycling of DAT in neurons and have validated the utility of these approaches. We have shown that extracellularly tagged DAT-HA and DAT-BBS retain active [3H]DA transport (Supplemental Fig. S2A) and are readily down-regulated in response to either AMPH or PMA (Figs. 3A and 4D, H). Binding of HA11 to DAT-HA or α-bungarotoxin to DAT-BBS does not appear to alter AMPH-induced DAT down-regulation (Supplemental Fig. S2B, C). Furthermore, such binding was not abolished by washes with high-salt acidic buffer of labeled cells, suggesting that they remain bound to the DAT as it traffics through acidic endosomes. Although antibody binding increases the molecular weight of labeled proteins and may affect their trafficking, a variety of controls presented in the results argue against this possibility (Fig. 3C), and similar antibody-feeding methods have been extensively used to study the recycling of neuronal membrane proteins (42, 43). As an alternative to antibody-based methods, DAT-BBS, with its specificity for a smaller ligand (α-bungarotoxin, 8 kD) and 1:1 binding stoichiometry can be used to further explore DAT trafficking, as shown previously for AMPA and GABAA receptors (44, 45).

CONCLUSIONS

The DAT serves as the primary mechanism for clearing DA following its release during neurotransmission, and the density of DAT proteins is a crucial determinant of DA signaling. The dynamic trafficking mechanisms that control the surface density of the DAT have received much attention because of their effect on dopaminegic neurotransmission and their link to psychostimulant drug action. Our work demonstrates that in DA neurons internalized DAT transits through different compartments after treatment with AMPH or PKC activators. PKC activation leads to ubiquitination-dependent degradation, whereas internalized DAT by AMPH undergoes recycling. Thus, the differential DAT sorting between recycling and degradative pathways may provide a mechanism for the adaptive changes in DAT activity that occur during normal neurotransmission and after psychostimulant exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yong-Jian Liu, Alexander Sorkin, Willi Halfter, Geoff Murdoch, Mee Choi, Linton Traub, Ora Weisz, Gerald Apodaca, and Katy Baty (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for valuable suggestions or various DNA constructs and antibodies. The authors also appreciate critiques from Spencer Watts, Mads Larsen, Ethan Block, Jie Jiang, and other members of the S.G.A. laboratory.

This work was supported by American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds and a U.S. National Institutes of Health grant (DA07595) to S.G.A.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- AMPH

- d-amphetamine

- BBS

- bungarotoxin-binding site

- BIM

- bisindolylmaleimide

- Btx-TMR

- α-bungarotoxin-tetramethylrhodamine

- DA

- dopamine

- DAT

- dopamine transporter

- DIV

- day in vitro

- E

- embryonic day

- EEA1

- early endosome antigen 1

- GAM

- goat anti-mouse IgG

- GAM-549

- goat anti-mouse IgG-DyLight549

- GAM-649

- goat anti-mouse IgG-DyLight649

- GAR-488

- goat anti-rabbit IgG-DyLight488

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- PBSCM

- phosphate-buffered saline with CaCl2 and MgCl2

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- ROI

- region of interest

- Tf-488

- transferrin-Alexa488

- TfR

- transferrin receptor

- TH

- tyrosine hydroxylase

REFERENCES

- 1. Fleckenstein A. E., Volz T. J., Riddle E. L., Gibb J. W., Hanson G. R. (2007) New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47, 681–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sulzer D. (2011) How addictive drugs disrupt presynaptic dopamine neurotransmission. Neuron 69, 628–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fleckenstein A. E., Metzger R. R., Wilkins D. G., Gibb J. W., Hanson G. R. (1997) Rapid and reversible effects of methamphetamine on dopamine transporters. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 282, 834–838 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saunders C., Ferrer J. V., Shi L., Chen J., Merrill G., Lamb M. E., Leeb-Lundberg L. M., Carvelli L., Javitch J. A., Galli A. (2000) Amphetamine-induced loss of human dopamine transporter activity: an internalization-dependent and cocaine-sensitive mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 6850–6855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sorkina T., Doolen S., Galperin E., Zahniser N. R., Sorkin A. (2003) Oligomerization of dopamine transporters visualized in living cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28274–28283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chi L., Reith M. E. (2003) Substrate-induced trafficking of the dopamine transporter in heterologously expressing cells and in rat striatal synaptosomal preparations. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 307, 729–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furman C. A., Chen R., Guptaroy B., Zhang M., Holz R. W., Gnegy M. (2009) Dopamine and amphetamine rapidly increase dopamine transporter trafficking to the surface: live-cell imaging using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. J. Neurosci. 29, 3328–3336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson L. A., Furman C. A., Zhang M., Guptaroy B., Gnegy M. E. (2005) Rapid delivery of the dopamine transporter to the plasmalemmal membrane upon amphetamine stimulation. Neuropharmacology 49, 750–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu S. J., Kavanaugh M. P., Sonders M. S., Amara S. G., Zahniser N. R. (1997) Activation of protein kinase C inhibits uptake, currents and binding associated with the human dopamine transporter expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 282, 1358–1365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Daniels G. M., Amara S. G. (1999) Regulated trafficking of the human dopamine transporter. Clathrin-mediated internalization and lysosomal degradation in response to phorbol esters. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35794–35801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Melikian H. E., Buckley K. M. (1999) Membrane trafficking regulates the activity of the human dopamine transporter. J. Neurosci. 19, 7699–7710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holton K. L., Loder M. K., Melikian H. E. (2005) Nonclassical, distinct endocytic signals dictate constitutive and PKC-regulated neurotransmitter transporter internalization. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 881–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miranda M., Dionne K. R., Sorkina T., Sorkin A. (2007) Three ubiquitin conjugation sites in the amino terminus of the dopamine transporter mediate protein kinase C-dependent endocytosis of the transporter. Mol. Biol. Cell. 18, 313–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hong W. C., Amara S. G. (2010) Membrane cholesterol modulates the outward facing conformation of the dopamine transporter and alters cocaine binding. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32616–32626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baker R., Johnson A. (1995) Nigral and striatal neurons. In Neural Cell Culture, A Practical Approach (Cohen J., Wilkin G.P., eds) pp. 25–40, Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang M., Chen G. (2006) High Ca2+-phosphate transfection efficiency in low-density neuronal cultures. Nat. Protoc. 1, 695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sorkina T., Miranda M., Dionne K. R., Hoover B. R., Zahniser N. R., Sorkin A. (2006) RNA interference screen reveals an essential role of Nedd4-2 in dopamine transporter ubiquitination and endocytosis. J. Neurosci. 26, 8195–8205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Blot V., McGraw T. E. (2008) Use of quantitative immunofluorescence microscopy to study intracellular trafficking: studies of the GLUT4 glucose transporter. Methods Mol. Biol. 457, 347–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mellman I., Plutner H., Ukkonen P. (1984) Internalization and rapid recycling of macrophage Fc receptors tagged with monovalent antireceptor antibody: possible role of a prelysosomal compartment. J. Cell Biol. 98, 1163–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sorkina T., Hoover B. R., Zahniser N. R., Sorkin A. (2005) Constitutive and protein kinase C-induced internalization of the dopamine transporter is mediated by a clathrin-dependent mechanism. Traffic 6, 157–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wanat M. J., Hopf F. W., Stuber G. D., Phillips P. E., Bonci A. (2008) Corticotropin-releasing factor increases mouse ventral tegmental area dopamine neuron firing through a protein kinase C-dependent enhancement of Ih. J. Physiol. 586, 2157–2170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malinow R., Malenka R. C. (2002) AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 25, 103–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park M., Penick E. C., Edwards J. G., Kauer J. A., Ehlers M. D. (2004) Recycling endosomes supply AMPA receptors for LTP. Science 305, 1972–1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Doolen S., Zahniser N. R. (2001) Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors alter human dopamine transporter activity in Xenopus oocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 296, 931–938 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carvelli L., Moron J. A., Kahlig K. M., Ferrer J. V., Sen N., Lechleiter J. D., Leeb-Lundberg L. M., Merrill G., Lafer E. M., Ballou L. M., Shippenberg T. S., Javitch J. A., Lin R. Z., Galli A. (2002) PI 3-kinase regulation of dopamine uptake. J. Neurochem. 81, 859–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moron J. A., Zakharova I., Ferrer J. V., Merrill G. A., Hope B., Lafer E. M., Lin Z. C., Wang J. B., Javitch J. A., Galli A., Shippenberg T. S. (2003) Mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates dopamine transporter surface expression and dopamine transport capacity. J. Neurosci. 23, 8480–8488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garcia B. G., Wei Y., Moron J. A., Lin R. Z., Javitch J. A., Galli A. (2005) Akt is essential for insulin modulation of amphetamine-induced human dopamine transporter cell-surface redistribution. Mol. Pharmacol. 68, 102–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kantor L., Gnegy M. E. (1998) Protein kinase C inhibitors block amphetamine-mediated dopamine release in rat striatal slices. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 284, 592–598 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boudanova E., Navaroli D. M., Melikian H. E. (2008) Amphetamine-induced decreases in dopamine transporter surface expression are protein kinase C-independent. Neuropharmacology 54, 605–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mortensen O. V., Larsen M. B., Prasad B. M., Amara S. G. (2008) Genetic complementation screen identifies a mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase, MKP3, as a regulator of dopamine transporter trafficking. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2818–2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wheeler D. S., Underhill S. M., Romero G., Amara S. G. (2011) Amphetamine triggers clathrin-independent internalization of the DAT by activating Rho family GTPases in a cAMP regulated fashion. Neuroscience 2011, Program No. 444.06 (Abstracts), Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC; http://www.abstractsonline.com [Google Scholar]

- 32. Doherty G. J., McMahon H. T. (2009) Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 857–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Foster J. D., Adkins S. D., Lever J. R., Vaughan R. A. (2008) Phorbol ester induced trafficking-independent regulation and enhanced phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter associated with membrane rafts and cholesterol. J. Neurochem. 105, 1683–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cremona M. L., Matthies H. J., Pau K., Bowton E., Speed N., Lute B. J., Anderson M., Sen N., Robertson S. D., Vaughan R. A., Rothman J. E., Galli A., Javitch J. A., Yamamoto A. (2011) Flotillin-1 is essential for PKC-triggered endocytosis and membrane microdomain localization of DAT. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 469–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matthies H. J., Moore J. L., Saunders C., Matthies D. S., Lapierre L. A., Goldenring J. R., Blakely R. D., Galli A. (2010) Rab11 supports amphetamine-stimulated norepinephrine transporter trafficking. J. Neurosci. 30, 7863–7877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rao A., Simmons D., Sorkin A. (2011) Differential subcellular distribution of endosomal compartments and the dopamine transporter in dopaminergic neurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 46, 148–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rao A., Richards T. L., Simmons D., Zahniser N. R., Sorkin A. (2012) Epitope-tagged dopamine transporter knock-in mice reveal rapid endocytic trafficking and filopodia targeting of the transporter in dopaminergic axons. FASEB J. 26, 1921–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. German C. L., Hanson G. R., Fleckenstein A. E. (2012) Amphetamine and methamphetamine reduce striatal dopamine transporter function without concurrent dopamine transporter relocalization. J. Neurochem. 123, 288–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eriksen J., Bjorn-Yoshimoto W. E., Jorgensen T. N., Newman A. H., Gether U. (2010) Postendocytic sorting of constitutively internalized dopamine transporter in cell lines and dopaminergic neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27289–27301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Loder M. K., Melikian H. E. (2003) The dopamine transporter constitutively internalizes and recycles in a protein kinase C-regulated manner in stably transfected PC12 cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22168–22174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sakrikar D., Mazei-Robison M. S., Mergy M. A., Richtand N. W., Han Q., Hamilton P. J., Bowton E., Galli A., Veenstra-Vanderweele J., Gill M., Blakely R. D. (2012) Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder-derived coding variation in the dopamine transporter disrupts microdomain targeting and trafficking regulation. J. Neurosci. 32, 5385–5397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tang T. T., Badger J. D., 2nd, Roche P. A., Roche K. W. (2010) Novel approach to probe subunit-specific contributions to N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor trafficking reveals a dominant role for NR2B in receptor recycling. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20975–20981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scott D. B., Michailidis I., Mu Y., Logothetis D., Ehlers M. D. (2004) Endocytosis and degradative sorting of NMDA receptors by conserved membrane-proximal signals. J. Neurosci. 24, 7096–7109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sekine-Aizawa Y., Huganir R. L. (2004) Imaging of receptor trafficking by using alpha-bungarotoxin-binding-site-tagged receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 17114–17119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bogdanov Y., Michels G., Armstrong-Gold C., Haydon P. G., Lindstrom J., Pangalos M., Moss S. J. (2006) Synaptic GABAA receptors are directly recruited from their extrasynaptic counterparts. EMBO J. 25, 4381–4389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.