Abstract

Interactions between the immune and skeletal systems in inflammatory bone diseases are well appreciated, but the underlying molecular mechanisms that coordinate the resolution phase of inflammation and bone turnover have not been unveiled. Here we investigated the direct actions of the proresolution mediator resolvin E1 (RvE1) on bone-marrow-cell-derived osteoclasts in an in vitro murine model of osteoclast maturation and inflammatory bone resorption. Investigation of the actions of RvE1 treatment on the specific stages of osteoclast maturation revealed that RvE1 targeted late stages of osteoclast maturation to decrease osteoclast formation by 32.8%. Time-lapse vital microscopy and migration assays confirmed that membrane fusion of osteoclast precursors was inhibited. The osteoclast fusion protein DC-STAMP was specifically targeted by RvE1 receptor binding and was down-regulated by 65.4%. RvE1 did not affect the induction of the essential osteoclast transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 (NFATc1) or its nuclear translocation; however, NFATc1 binding to the DC-STAMP promoter was significantly inhibited by 60.9% with RvE1 treatment as shown in electrophoresis mobility shift assay. Our findings suggest that proresolution mediators act directly on osteoclasts, in addition to down-regulation of inflammation, providing a novel mechanism for modulating osteoclast signaling in osteolytic inflammatory disease.—Zhu, M., Van Dyke, T. E., Gyurko, R. Resolvin E1 regulates osteoclast fusion via DC-STAMP and NFATc1.

Keywords: osteoimmunology, inflammation resolution, lipid mediator

Inflammatory bone diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, postmenopausal osteoporosis, and periodontitis are characterized by chronic infiltration of affected tissues by neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells, followed by osteoclast activation, accelerated bone turnover and eventual bone loss (1–3). Eicosanoids, including prostaglandins and leukotrienes, play an important role in osteoimmunological lesions, displaying potent actions in both inflammation and bone resorption (4). Recent studies have uncovered novel lipid-derived mediators in inflammatory exudates that promote the resolution phase of inflammation (5). This new genus of specific proresolving lipid mediators includes lipoxins from arachidonic acid, resolvins, and protectins from ω-3 essential fatty acids. Lipoxin and resolvin formation is temporally dissociated from other eicosanoids (6–9). This class of molecules mediates resolution of inflammation, an active, highly coordinated program (10, 11). Failure of resolution of inflammation can lead to chronic inflammation, including inflammatory bone diseases (12). Resolvin E1 (RvE1; 5S,12R,18R-trihydroxy-6Z,8E,10E,14Z,16E-eicosapentaenoic acid) is derived from the ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), eicosapentaenoic acid. RvE1 down-regulates inflammation in vivo in peritonitis, allergic airway inflammation, and periodontitis on the molecular and histological level (13–16). RvE1 acts through the cell surface receptors chemokine-like receptor 1 (CMKLR1) and BLT-1, a leukotriene receptor (17).

Studies of inflammatory bone diseases have highlighted the importance of the interaction between the immune and skeletal systems (18) that share cytokines and various signaling molecules. Extensive molecular crosstalk exists between the inflammatory mediators and the regulators of bone turnover (19). Shared cell lineages have also been discovered, as the osteoclast is derived from monocyte-macrophage lineage of hematopoietic stem cells in response to monocyte colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL). Osteoclasts develop from mononuclear precursors that fuse to form multinuclear mature osteoclasts capable of bone resorption. The fusion of osteoclasts is the basis for efficient resorption of bone (20). Fusion increases the size of osteoclasts, enabling resorption of larger areas of bone tissue that are firmly covered (21). Fusion-incompetent osteoclasts can resorb bone but with greatly impaired efficiency (22). Osteoclast fusion is a complex process with a number of fusion proteins involved, including macrophage fusion receptor (MFR; ref. 23), v-ATPase subunit d2 (ATP6v0d2; ref. 24), and dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP; ref. 25). Among them, DC-STAMP was shown to be an essential molecule for mononuclear osteoclast fusion and giant cell formation (22). DC-STAMP is directly induced by the transcription factor, nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 (NFATc1), in osteoclasts along with ATP6v0d2 (26). Moreover, NFATc1 has been reported to be an essential RANKL-inducible gene specifically required for the terminal differentiation of osteoclasts (27).

With the paradigm shift in the approach to chronic inflammatory diseases from “anti-inflammation” to “resolution of inflammation,” the question arises whether molecules involved in inflammation resolution also contribute to the progression or reversal of inflammatory bone diseases. Interesting studies using a rabbit periodontitis model have shown that treatment of existing periodontal disease with RvE1 results in resolution of the inflammatory lesion with regeneration of bone and the periodontal attachment (14). Previously published work revealed that RvE1 directly inhibits mature osteoclast formation and bone resorption in vitro (28, 29). The underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for RvE1 actions on osteoclasts are unknown. Data presented here show that RvE1 effectively inhibits osteoclast formation and function by exclusively targeting and disrupting osteoclast fusion. The essential osteoclast fusion protein DC-STAMP is significantly down-regulated by RvE1 and RvE1 receptor signaling decreases binding of NFATc1 to the DC-STAMP promoter. These findings indicate that inflammation resolution programs affect bone metabolic pathways to restore tissue homeostasis and suggest a potential role for RvE1 in the restoration/regeneration of bone tissue in osteolytic inflammatory diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Osteoclast culture

Bone marrow cells were harvested from 4- to 6-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Boston University and performed in conformance to the standards of the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Bone marrow cells were plated in 24-well plates (1×106 cells/well) or 6-well plates (5×106 cells/well). Cells were cultured in osteoclast differentiating medium (OC medium) containing α-MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, USA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 30 ng/ml M-CSF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) and 30 ng/ml RANKL (Peprotech). Multinuclear osteoclast-like cells started to appear at the end of d 4; osteoclastogenesis was evaluated by tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining as described previously (28). Digital images of the cell culture were taken at ×25 using an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200, Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) with a video camera. Color images were converted to black-and-white (TRAP-positive cells with red color were converted to black) and digitally filtered to remove cells with <3 nuclei using the image analysis software Olympus MicroSuite (Olympus America, Melville, NY, USA). Data were expressed as the percentage of total culture dish area covered by TRAP-stained cells with ≥3 nuclei (osteoclast-covered area).

RvE1 and control treatment

RvE1 was produced through total organic synthesis (17). RvE1 was stored in 100% ethanol and diluted in cell culture medium or PBS immediately before use. The final concentration of RvE1 used was 10 nM based on our prior study (28). The control (vehicle) treatment was the identical culture medium or PBS supplemented with the corresponding amount of ethanol. The final ethanol concentration never exceeded 1%.

Flow cytometry

Differentiated osteoclasts were harvested using EDTA and fixed in 50 μl 3% formalin/PBS for 30 min on ice, washed by centrifugation at 2000 rpm in 250 μl PBS. Cells were incubated with FITC-anti-CD11b (1:100, M1/70; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), APC-anti-c-fms (1:100, AFS98; eBioscience) and PE-anti-RANK (1:100, R12-31; eBioscience) antibodies for 1 h on ice and with individual antibodies and isotype-matched negative control IgG. Cells were washed 3 times by centrifugation at 300 g in 250 μl PBS containing 5% FBS. For assessment of BLT-1, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) after surface staining using APC-eFluor780-anti-CD11b (1:100, M1/70, eBioscience), APC-anti-c-fms (1:100, AFS98; eBioscience) and PE-anti-RANK (1:100, R12-31; eBioscience) antibodies. Cells were then stained in the dark on ice with Alexa Fluor 488-anti-BLT-1 antibody (1:50; Bioss, Woburn, MA, USA) for 30 min and washed 3 times. Flow cytometry was performed using LSRII (BD Biosciences) and FACS Diva 6.0 software (BD Biosciences).

Time-lapse video microscopy

Bone marrow cells were cultured in 8-well glass-bottom chamber slides in OC medium for 3 d. The culture chamber slides were placed on the stage of a Zeiss Axiovert 200M LSM 510 laser scanning confocal microscope in an environmental chamber maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. After differentiated mononuclear osteoclasts were treated with RvE1 or vehicle, cell fusion was monitored using the multitime module in the LSM software, allowing multiple locations to be observed over time. Images were taken automatically at each location in 15-min intervals for 17 h. Autofocus was used before the first image at each time point was acquired. Using LSM imaging software, the number of nuclei of multinuclear osteoclasts was counted and the fusion intervals were recorded to calculate the fusion speed. For measuring migration speed, the leading edge of osteoclasts was recorded at each interval and the migration path over time was reconstructed.

Transwell migration assay

Bone marrow cells were cultured in OC medium for 3 d. Mononuclear cells were harvested using EDTA and resuspended in migration buffer (serum-free α-MEM containing 30 ng/ml RANKL) at a concentration of 106 cells/ml. Migration buffer (800 μl), with or without M-CSF (30 ng/ml) as chemotactic reagent, was placed in the wells of 24-well plate. Costar Transwell inserts (6.5 mm-diameter polycarbonate membranes, 8-μm pore size; Corning, Lowell, MA, USA) were placed into the wells, and 100 μl of the cell suspension was added to the upper chamber of the inserts. Cells were allowed to migrate at 37°C overnight, and TRAP staining was performed on the cells in the lower chamber. Migrated TRAP-positive mononuclear cells were counted in 5 randomly selected microscope fields at ×400. In separate experiments, cells that migrated through the Transwell inserts were further cultured in OC medium for an additional 24 h and stained for TRAP to assess fusion of the transmigrated osteoclast precursors.

RT-PCR analysis

Total cellular RNA was extracted from osteoclasts using TriZol reagent (Invitrogen), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized with High Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For the semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis, amplifications were carried out with HotStartTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) with the following specific primers: mouse DC-STAMP (322 bp), 5′-TGGAAGTTCACTTGAAACTACGTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTCGGTTTCCCGTCAGCCTCTCTC-3′ (antisense); mouse ATP6v0d2 (248 bp), 5′-TCAGATCTCTTCAAGGCTGTGCTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTGCCAAATGAGTTCAGAGTGATG-3′ (antisense); mouse MFR (220 bp), 5′-AAATCAGTGTCTGTTGCTGCTGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTGGGGTGACATTACTGATAC-3′ (antisense); mouse GAPDH (256 bp), 5′-AATGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTAT-3′ (antisense). The PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

For quantitative RT-PCR analysis, oligonucleotides for RANK, NFATc1, and hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 (HPRT1) were chosen from predesigned assays, while oligonucleotides for DC-STAMP were custom made by Applied Biosystems. Thermal cycling included initial steps at 50°C for 2 min and at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and at 60°C for 1 min. The fluorescence of the double-stranded products was monitored in real time. The cDNA was amplified and quantified using Sequence Detection System (SDS) 7000 (Applied Biosystems). Experiments were performed 3 times, in triplicate wells. Data elaboration was performed as relative quantification analysis using the ΔΔCt method. Data were normalized with an internal HPRT1 control. Gene expression in the RvE1 treatment group was expressed relative to the control group gene expression profile.

Western blotting

Whole-cell proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer as previously described (28), and the nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were extracted using NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific), and samples of same amount were electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (65 mA, 4°C, overnight). After blocking with 5% skim milk for 60 min at room temperature, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against DC-STAMP (1:200, M-240; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or NFATc1(1:200, 7A6; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HPR)-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, and the bound antibodies were visualized with HPR chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific), followed by exposure to X-ray film. Quantification was carried out by measuring band density using a GS-710 calibrated imaging densitometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as control for cytosolic protein contamination in nuclear extract, while lamin B1 and actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used as loading controls for nuclear and whole-cell proteins, respectively.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Oligonucleotides from the mouse DC-STAMP promoter containing NFATc1 binding site (wild-type) or a mutant were obtained from Invitrogen. The sequences are as follows, with the NFATc1 binding site underscored: wild type, 5′-GAGCAGGGAGGAAAAAGGGAAGGAAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTTCCTTCCCTTTTTCCTCCCTGCTC-3′ (antisense); mutant, 5′-GAGCAGGGATTCCAAAGGGAAGGAAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTTCCTTCCCTTTGGAATCCCTGCTC-3′ (antisense). Wild-type oligonucleotides were end-labeled with biotin using a biotin 3′-end labeling kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary oligonucleotides were annealed for labeled probes, wild-type cold competitors, and mutant cold competitors, respectively.

Binding reactions (20 μl) were prepared with 5 μg of nuclear extract, 1 μg poly dI/dC in binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 100 mM KCl; 1 mM EDTA; 10% glycerol; and 1 mM DTT; Thermo Scientific), and 20 fmol-labeled probe and incubated 20 min at room temperature. For competition assays, unlabeled wild-type and mutant probes were added at 200× of the concentration of the labeled probe. When indicated, anti-NFATc1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and nonspecific control antibody (anti-GST; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1 μg each) were added to binding reactions. Samples were resolved by electrophoresis on 6% native polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× Tris-buffered EDTA (TBE) and transferred onto nylon membranes (Thermo Scientific). The membranes were stained and visualized using chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by exposure to X-ray film.

Statistics

Unless otherwise specified, each experiment was repeated ≥3 times. Results are expressed as means ± se. Comparisons between 2 groups were analyzed using Student's 2-tailed unpaired t test. One-way analysis of variance and Scheffe's post hoc multiple comparisons were used for comparisons among ≥3 groups. Repeated 1-way analysis of variance was used for comparisons between 2 groups temporally. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

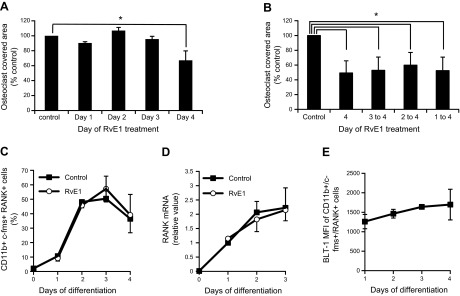

RvE1 in osteoclast differentiation

On treatment with RANKL, osteoclast precursors differentiate from the monocyte/macrophage lineage of hematopoietic cells and fuse into bone-resorbing multinuclear osteoclasts. RvE1 inhibits mature osteoclast formation and limits bone resorption (28). To identify the specific osteoclast maturation stage that RvE1 affects, an in vitro model for osteoclast differentiation was used. Culture of bone marrow cells from 4- to 6-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice in OC medium resulted in the development of multinuclear TRAP-positive cells in 4 d. To determine which phase of osteoclast differentiation RvE1 affects, osteoclast cultures were treated with 10 nM RvE1 for a 24-h interval on either d 1, 2, 3, or 4. For example, in the d 2 treatment group, cells were grown in OC medium on d 1, then RvE1 was added during d 2, and RvE1 was removed from the culture medium for d 3 and 4. For all treatment groups, the experiment was terminated at the end of d 4, and osteoclast-covered area was determined after TRAP staining. RvE1 treatment on d 4 decreased osteoclast formation by 32.8%, but treatment on d 1, 2, or 3 had no effect (Fig. 1A). To rule out the possibility that metabolism of RvE1 underlies the absence of early effects of RvE1, RvE1 treatment of the osteoclast culture was started on d 1, 2, 3, or 4 and continued until the end of d 4. RvE1 treatment that begun on d 4 mimicked the other RvE1-treated groups (Fig. 1B). Day 4 corresponds to the migration and fusion stage of osteoclasts in vitro, indicating that RvE1 affects late stage of osteoclast maturation.

Figure 1.

RvE1 inhibits at late stages of osteoclast formation but does not influence early osteoclast precursor development. A) RvE1-induced changes in multinuclear osteoclast formation. RvE1 (10 nM) was administered for a 24-h period on d 1, 2, 3, or 4. Control cells received vehicle only. TRAP staining was performed at the end of d 4. Percentage of culture dish covered with TRAP-positive multinuclear cells is shown. B) Osteoclast formation with RvE1 treatment started on d 1, 2, 3, or 4 and continued through the end of d 4. C) Quantification of CD11b+/c-fms+/RANK+ osteoclast precursors in osteoclast differentiation culture on d 1, 2, or 3, 24 h after 10 nM RvE1 or vehicle treatment, analyzed by flow cytometry. D) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of RANK mRNA expression on osteoclast culture treated with 10 nM RvE1 or vehicle continuously along with differentiation as indicated. mRNA levels were normalized to d 1 control. E) Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of BLT-1 on CD11b+/c-fms+/RANK+ osteoclast precursors in osteoclast differentiation culture on d 1, 2, 3, or 4, analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are presented as means ± se from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (ANOVA with Scheffe's post hoc multiple comparisons).

RvE1 does not alter early osteoclast precursor differentiation

Cell surface markers correlating with osteoclast differentiation from murine bone marrow cells include c-fms, CD11b, and RANK (30). The earliest identifiable step in osteoclast differentiation is up-regulation of c-fms (M-CSF receptor) and CD11b (MAC-1). Late osteoclast precursors begin to express RANK, the surface receptor for RANKL, while maintaining c-fms expression. CD11b is lost in multinuclear osteoclasts. Using flow cytometry, we found that the number of CD11b+, c-fms+, RANK+ osteoclast precursors increased in the first 3 d after M-CSF and RANKL induction and declined on d 4 (Fig. 1C). RvE1 treatment (10 nM) of osteoclast cultures had no effect on the rate or extent of osteoclast precursor development (Fig. 1C). RANK gene expression monitored separately with real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) confirmed that sustained RvE1 (10 nM) does not change RANK expression in osteoclast cultures (Fig. 1D). Although osteoclasts express both BLT-1 and CMKLR1 receptors, RvE1 binds to BLT-1 but not to CMKLR1 on osteoclasts (28). To explore the possibility that lack of RvE1 effect at early time point of osteoclast differentiation is related to the receptor availability, the relative expression of BLT-1 during the 4 d time course of osteoclast differentiation was determined by flow cytometry. We found that BLT-1 expression is present from d 1, and it does not change significantly during osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 1E).

RvE1 inhibits osteoclast fusion

Cell fusion is a critical step in osteoclast differentiation. Development of multinuclear giant cells is necessary for efficient osteoclast function (22). We examined the effect of RvE1 on osteoclast fusion using time-lapse video microscopy. Cells from 3-d-old murine osteoclast cultures were incubated in an environmental chamber (37°C, 5% CO2) mounted on a confocal microscope (Axiovert 200M LSM 510 laser scanning microscope; Zeiss) overnight. The numbers of nuclei per osteoclast were counted, and the fusion intervals were recorded to calculate fusion speed. RvE1 treatment (10 nM) reduced osteoclast fusion speed when compared to control (control: 1.5±0.032 fusion/h, RvE1: 1.3±0.038 fusion/h, P<0.05; Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

RvE1 inhibits fusion of osteoclasts precursors. A) Osteoclast fusion analysis using time-lapse video microscopy. On live 3-d-old osteoclast cultures, phase-contrast microscopic images at ×600 were taken every 15 min for 17 h. Number of nuclei of multinuclear osteoclasts was counted, and the fusion intervals were recorded to calculate the fusion speed. Data are presented as means ± se. B) Transwell migration assay using M-CSF as chemotactic reagent to access the chemotactic migration of mononuclear osteoclast. TRAP staining was performed on the lower chamber after migration overnight, and the TRAP-positive mononuclear cells were counted. Data are presented as means ± se from 2 independent experiments. C) Transmigrated cells from separate Transwell migration assay as above were cultured for another 24 h, and the nuclei of multinuclear cells were analyzed. Data are presented as means ± se from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (2-tailed Student's t test).

Migration of competent mononuclear osteoclast precursors toward each other is a prerequisite for fusion (31). We monitored osteoclast precursor migration with time-lapse video microscopy. The average speed of mononuclear osteoclast migration was not significantly different in RvE1-treated osteoclasts (RvE1: 0.71±0.05 μm/min, control: 0.91±0.15 μm/min). To further evaluate the actions of RvE1 on osteoclast precursor migration, a Transwell migration assay was performed, using M-CSF (30 ng/ml) as the chemoattractant. After overnight incubation, transmigrated mononuclear osteoclast precursors were identified by TRAP staining. RvE1 treatment did not change the number of migrated osteoclast precursors (Fig. 2B). In separate experiments, transmigrated cells were further cultured in OC medium for another 24 h to allow for cell fusion. Nuclei of cells with ≥3 nuclei were counted, representing the migrated osteoclast precursors that are able to fuse. Nuclear counts in fused osteoclasts were lower in the RvE1 treatment group (Fig. 2C), further confirming that RvE1 inhibits fusion of osteoclast precursors.

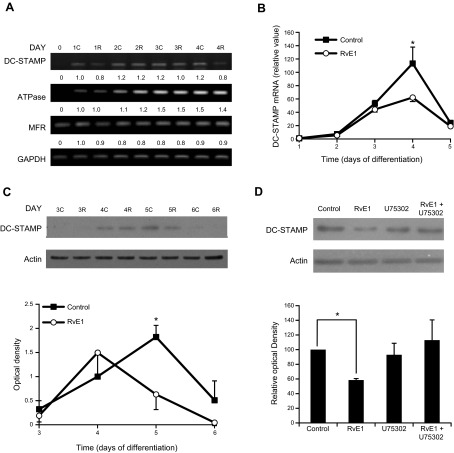

RvE1 specifically down-regulates the essential fusion protein DC-STAMP through the resolvin receptor BLT-1

To determine the effect of RvE1 on osteoclast fusion, the expression of fusion proteins, including MFR, ATP6v0d2, and DC-STAMP was examined by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and qPCR. In 4-d-old osteoclast cultures, RT-PCR results (Fig. 3A) showed a decrease of DC-STAMP mRNA expression with RvE1 treatment compared with control, while no difference was detected on d 1, 2, and 3. No significant difference was detected in mRNA expression of MFR or ATP6v0d2. qPCR confirmed that DC-STAMP mRNA expression significantly decreased after RvE1 treatment of d 4 cultures by 45.1% (Fig. 3B). DC-STAMP protein levels were also reduced by 65.4%, as determined in protein extracts from 3- to 6-d-old osteoclast cultures (Fig. 3C). Quantification of immunoblots revealed that there was significant decrease in DC-STAMP protein expression in RvE1-treated 5-d-old osteoclast cultures.

Figure 3.

RvE1 specifically inhibits expression of osteoclast fusion protein DC-STAMP. A) RT-PCR analysis of osteoclast fusion protein DC-STAMP, ATP6v0d2, and MFR mRNA expression of osteoclast culture after RvE1 (R) or control (C) treatments. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Numbers below the bands indicate relative densitometric values as compared to RvE1 treatment group on d 1. B) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of DC-STAMP mRNA expression. Data are presented as means ± se from 6 independent experiments. C) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of DC-STAMP protein expression. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (top panel) or presented as means ± se from 3 independent experiments (bottom panel). D) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of DC-STAMP protein on d 5 osteoclast differentiation culture. RvE1 (10 nM) and/or BLT-1 specific antagonist U75302 (1 nM) were used based on prior experiments (28) as indicated. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (top panel) or presented as means ± se from 3 independent experiments (bottom panel). *P < 0.05 (2-tailed Student's t test).

RvE1 binds to BLT-1 on osteoclasts (28). To determine whether RvE1 inhibits DC-STAMP expression through BLT-1 receptor signaling, osteoclast cultures were treated with the BLT-1-specific receptor antagonist U75302. We have shown previously that U75302 (1 nM) effectively reverses RvE1's inhibitory action on osteoclast differentiation (28). Here we report that U75302 treatment prevented RvE1-induced decreases in DC-STAMP protein, while U75302 alone had no effect on DC-STAMP expression (Fig. 3D).

RvE1 blocks NFATc1 signaling

NFATc1 is an intracellular master regulator of terminal osteoclastogenesis (32). Ectopic NFATc1 expression enables bone marrow cells to undergo osteoclast differentiation even in the absence of RANKL (27), while the osteoclast-specific conditional NFATc1-deficient mice exhibit osteopetrosis (33). The evidence that NFATc1 directly induce DC-STAMP expression (26) strongly suggests an inhibitory effect of RvE1 on osteoclast NFATc1. There are 3 steps in NFATc1 activation of transcription: autoamplification, translocation, and binding. We first investigated RvE1 actions in NFATc1 autoamplification in osteoclasts. Cells of d 4 cultures were treated with RANKL in the presence or absence of RvE1 (10 nM), and RNA was extracted. qPCR results revealed that NFATc1 mRNA levels increase 4 h after RANKL treatment, then gradually returned to baseline after 8 h; RvE1 induced no detectable change (Fig. 4A). After activation, NFATc1 is dephosphorylated and translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus. We monitored NFATc1 nuclear translocation in cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extracts with Western blotting and found that RvE1 does not affect NFATc1 nuclear translocation (Fig. 4B, C).

Figure 4.

RvE1 interferes with binding of osteoclast transcription factor NFATc1 to DC-STAMP promoter. A) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of NFATc1 mRNA expression after RvE1 or vehicle treatment for 2–24 h on d 4 culture. Data are presented as means ± se from 3 independent experiments. B, C) Immunoblot and densitometric analysis of NFATc1 nuclear protein (B) and total protein (C) after RvE1 or control treatment for 5 min to 4 h on d 4 culture. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments (top panel) or presented as means ± se from 4 independent experiments (bottom panel). D) EMSA of nuclear extracts (NE) of d 4 osteoclasts after 1 h RvE1 or control treatment, with an oligonucleotide from DC-STAMP promoter containing NFATc1 binding site; competition analysis with 200-fold excess unlabeled competitor (cold complete) or mutant oligonucleotides (MT complete); and supershift analysis of nuclear extract with anti-NFATc1 or anti-GST antibody. Arrow indicates the shifted band. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

The direct binding of NFATc1 to the DC-STAMP promoter was assessed by EMSA. DNA oligonucleotides corresponding to the NFATc1 binding site in the mouse DC-STAMP promoter were designed and end-labeled with biotin. Nuclear extracts from d 4 osteoclast cultures treated with RvE1 or vehicle for 1 h were examined. NFATc1 binding to the DC-STAMP promoter sequence induced a characteristic band shift (Fig. 4D, lane 2) that was inhibited by RvE1 (Fig. 4D, lane 3). The band density after RvE1 treatment was decreased by 60.9% compared to the control. Unlabeled DC-STAMP promoter oligonucleotides at 200-fold molar excess completely blocked the band shift (Fig. 4D, cold complete, lanes 4 and 5), while mutant (Fig. 4D, MT complete, lanes 8 and 9) oligonucleotides did not, confirming the sequence specificity of oligonucleotide binding. In addition, anti-NFATc1 antibody decreased the density of shifted bands (Fig. 4D, lanes 6 and 7), while nonspecific antibody did not (Fig. 4D, lanes 10 and 11).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of inflammatory osteolytic diseases continues to grow with the increasing age of the population, affecting the quality of life of millions of people (34, 35). The clinical responses to current therapies, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, cytokine receptor antagonists, corticosteroids, or antiosteoclast agents, is variable, and the side effect profile of prolonged use of these drugs is not favorable (36, 37). Unlike current therapeutics that block enzyme activity or antagonize receptors, eicosanoids that mediate resolution of inflammation are receptor agonists (38). The findings described here establish the molecular mechanism for a novel target cell of RvE1, the osteoclast. In osteoclasts, RvE1 specifically targets and down-regulates the pivotal fusion protein DC-STAMP and decreases the DNA binding activity of the transcription factor NFATc1, leading to decreased cell fusion and attenuated bone resorption. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the molecular mechanism of interaction between inflammation resolution and bone homeostasis. The understanding of a detailed map and molecular appreciation of the resolution programs for bone related inflammation and tissue damage provides a powerful tool for understanding the potential of resolution agonists for future therapy.

In bone-related inflammatory diseases, activated immune cells release proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes (39). Many of these factors regulate osteoclastogenesis from early stages to RANKL signaling (40, 41). Unlike proinflammatory mediators, the endogenously produced proresolving lipid mediator RvE1 does not affect the early stage of osteoclast formation but specifically limits the fusion process. The timing of RvE1 effect is consistent with the temporal generation of RvE1 through cell-cell interaction during the inflammation resolution phase (38). RvE1 dampens excess osteoclast function in inflammatory bone diseases, while maintaining basic functionality to promote homeostasis. A basic characteristic of all resolution agonists is their ability to drive an inflammatory destructive lesion back to homeostasis (38). Inherent in this statement is the observation that the actions of resolvins do not block cell function, but eliminate excess function. The hypothesis is that resolvins induce return to homeostasis through the coordinated regulation of cell processes that limit tissue destruction by inflammation. Here we provide another example of this principle. By limiting osteoclast fusion, RvE1 dampens the inflammation-induced bone resorption associated with chronic osteolytic diseases, promoting a shift from bone resorption to bone formation that allows for healing with return to predisease homeostasis, as seen in the treatment of periodontitis with complete regeneration of lost hard tissues (42).

Cellular fusion is a basic property of osteoclasts with great biological significance; osteoclasts are efficient bone-resorbing cells because of the increased size and local resorptive area of multinuclear cells (21). The relationship of nuclei number and osteoclast resorption efficiency is not linear; small reductions in nuclei per cell have a large effect on bone resorption (20). The time-lapse video microscopy study gave a visual clue that RvE1 inhibits osteoclast fusion at the cellular level. We have previously reported a significant shift to lower nuclear counts in mature osteoclasts with RvE1 treatment (28). The detection of down-regulation of DC-STAMP mRNA and protein expression after RvE1 treatment provides molecular evidence of the RvE1 inhibition of the osteoclast fusion pathway. The decline in DC-STAMP mRNA coincides with the decrease in cell fusion at d 4; however, Western blotting shows only decreased DC-STAMP signal after 5 d of RvE1 treatment. The cause of this apparent discrepancy is presently unknown; however, differential decrease in cell surface versus intracellular DC-STAMP levels along with the limited sensitivity of the quantification methods for Western blotting may underlie the apparent delayed protein response. DC-STAMP was originally identified in dendritic cells (43). DC-STAMP plays an essential role in the formation of multinuclear osteoclasts as demonstrated by DC-STAMP defective mice that show an osteopetrotic phenotype (22). Our results are consistent with observations by others (44) showing that docosahexaenoic acid significantly inhibits DC-STAMP mRNA expression, indicating that DC-STAMP might be a common target of PUFAs and their metabolites.

The BLT1 receptor mediates RvE1 actions on osteoclast fusion, as BLT1 is expressed in osteoclasts and their mononuclear precursors, and inhibition of BLT1 receptors prevents RvE1-induced inhibition of DC-STAMP expression. It has been shown that LTB4 stimulates osteoclast formation (45) and increases the osteoclast activity through the BLT1-Gi protein-Rac1 signaling pathway (46). RvE1 competes the binding of LTB4 to BLT-1 (28), which is partially responsible for attenuation of LTB4's potent activation of osteoclast function. However, the results presented here are consistent with RvE1 agonist actions (47). RvE1 inhibits NFATc1 binding, which is distinct from the LTB4/BLT-1 induced signaling pathway (46), suggesting that both mechanisms are operating.

The RANKL-induced transcription factor NFATc1 is an essential regulator during terminal differentiation of osteoclasts (32). Activation of nuclear factor-κB by RANKL in the early phase of osteoclastogenesis is important for the initial induction of NFATc1 (27, 48). NFATc1 undergoes autoamplification after activation by calcium signaling and with the help of activator protein-1 containing c-fos (49). Sufficient amounts of activated NFATc1 in the nucleus is pivotal in inducing the expression of osteoclast specific genes, such as TRAP (27), cathepsin K (50), calcitonin receptor r (27), and DC-STAMP (51). Our data show that there is no significant difference in total NFATc1 protein between RvE1 and control treatment, indicating that RvE1 did not affect NFATc1 autoamplification. However, RvE1 decreased the binding of NFATc1 to the DC-STAMP promoter, indicating that RvE1 may act in the nucleus in regulating DC-STAMP. Post-translational modifications of NFATc1, such as phosphorylation, are potential targets for RvE1 regulation of protein-DNA interactions (52).

These findings markedly expand the role of RvE1 in inflammatory bone diseases. In addition to its proresolving action that dampens the inflammatory response, RvE1 also independently and directly inhibits osteoclast fusion, leading to attenuated bone resorption. In physiological conditions, osteoblasts regulate osteoclast differentiation and function through a process termed “coupling” that leads to balanced bone resorption and formation (53, 54). In disease states, osteoclasts and osteoblasts may become uncoupled, leading to increased bone resorption and decreased bone formation or vice versa (55). By correcting excessive osteoclast activity in inflammation, proresolving mediators such as RvE1 may restore the normal coupling process as well. Previous studies in animal models demonstrate bone- and soft tissue protection and regeneration with RvE1 treatment in collagen-induced arthritis and periodontitis (14). Future therapeutic strategies for chronic inflammatory bone diseases might include restoring the balance of proresolving mediators at the affected site.

Together, our results provide evidence that binding of the inflammation resolving mediator RvE1 to the BLT1 receptor on osteoclasts is bone protective, selectively inhibiting osteoclast fusion through down-regulation of pivotal fusion protein DC-STAMP. RvE1 and related mimetics could provide novel therapeutic approaches to the treatment of inflammatory disease that involve bone loss.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. B. S. Nikolajczyk and Dr. V. Trinkaus-Randall for technical support and discussion. RvE1 was kindly provided by Dr. C. N. Serhan, (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA).

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant DE19938 from the National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

M.Z. designed and carried out experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; T.E.V.D. was involved in experimental design and provided reagents, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript; R.G was involved in experimental design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. Conflicts of interest: T.E.V.D. is an inventor on patents (resolvins) assigned to Boston University and licensed to Resolvyx Pharmaceuticals. T.E.V.D. is a scientific founder of Resolvyx Pharmaceuticals and owns equity in the company. T.E.V.D.'s interests were reviewed and managed by Boston University and now the Forsyth Institute in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

Footnotes

- CMKLR1

- chemokine-like receptor 1

- DC-STAMP

- dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- HPRT1

- hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase 1

- M-CSF

- macrophage-colony stimulating factor

- MFR

- macrophage fusion receptor

- NFATc1

- nuclear factor of activated T cells c1

- PUFA

- polyunsaturated fatty acid

- RANK

- receptor activator of nuclear factor κB

- RANKL

- receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand

- RvE1

- resolvin E1

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

REFERENCES

- 1. Galkina E., Ley K. (2009) Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of atherosclerosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 165–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Dyke T. E. (2008) The management of inflammation in periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 79, 1601–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. El-Gabalawy H., Guenther L. C., Bernstein C. N. (2010) Epidemiology of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: incidence, prevalence, natural history, and comorbidities. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 85, 2–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hikiji H., Takato T., Shimizu T., Ishii S. (2008) The roles of prostanoids, leukotrienes, and platelet-activating factor in bone metabolism and disease. Prog. Lipid Res. 47, 107–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Serhan C. N., Savill J. (2005) Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1191–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fierro I. M., Kutok J. L., Serhan C. N. (2002) Novel lipid mediator regulators of endothelial cell proliferation and migration: aspirin-triggered-15R-lipoxin A(4) and lipoxin A(4). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 300, 385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Serhan C. N., Hong S., Gronert K., Colgan S. P., Devchand P. R., Mirick G., Moussignac R. L. (2002) Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J. Exp. Med. 196, 1025–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ariel A., Li P. L., Wang W., Tang W. X., Fredman G., Hong S., Gotlinger K. H., Serhan C. N. (2005) The docosatriene protectin D1 is produced by TH2 skewing and promotes human T cell apoptosis via lipid raft clustering. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 43079–43086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Serhan C. N., Yang R., Martinod K., Kasuga K., Pillai P. S., Porter T. F., Oh S. F., Spite M. (2009) Maresins: novel macrophage mediators with potent antiinflammatory and proresolving actions. J. Exp. Med. 206, 15–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Serhan C. N. (2011) The resolution of inflammation: the devil in the flask and in the details. FASEB J. 25, 1441–1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Serhan C. N. (2010) Novel lipid mediators and resolution mechanisms in acute inflammation: to resolve or not? Am. J. Pathol. 177, 1576–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nathan C., Ding A. (2010) Nonresolving inflammation. Cell 140, 871–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bannenberg G. L., Chiang N., Ariel A., Arita M., Tjonahen E., Gotlinger K. H., Hong S., Serhan C. N. (2005) Molecular circuits of resolution: formation and actions of resolvins and protectins. J. Immunol. 174, 4345–4355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hasturk H., Kantarci A., Ohira T., Arita M., Ebrahimi N., Chiang N., Petasis N. A., Levy B. D., Serhan C. N., Van Dyke T. E. (2006) RvE1 protects from local inflammation and osteoclast-mediated bone destruction in periodontitis. FASEB J. 20, 401–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haworth O., Cernadas M., Yang R., Serhan C. N., Levy B. D. (2008) Resolvin E1 regulates interleukin 23, interferon-gamma and lipoxin A4 to promote the resolution of allergic airway inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 9, 873–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ariel A., Fredman G., Sun Y. P., Kantarci A., Van Dyke T. E., Luster A. D., Serhan C. N. (2006) Apoptotic neutrophils and T cells sequester chemokines during immune response resolution through modulation of CCR5 expression. Nat. Immunol. 7, 1209–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arita M., Bianchini F., Aliberti J., Sher A., Chiang N., Hong S., Yang R., Petasis N. A., Serhan C. N. (2005) Stereochemical assignment, anti-inflammatory properties, and receptor for the omega-3 lipid mediator resolvin E1. J. Exp. Med. 201, 713–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakashima T., Takayanagi H. (2009) Osteoimmunology: crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. J. Clin. Immunol. 29, 555–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raggatt L. J., Partridge N. C. (2010) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25103–25108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ishii M., Saeki Y. (2008) Osteoclast cell fusion: mechanisms and molecules. Mod. Rheumatol. 18, 220–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Teitelbaum S. L. (2000) Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 289, 1504–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yagi M., Miyamoto T., Sawatani Y., Iwamoto K., Hosogane N., Fujita N., Morita K., Ninomiya K., Suzuki T., Miyamoto K., Oike Y., Takeya M., Toyama Y., Suda T. (2005) DC-STAMP is essential for cell-cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Exp. Med. 202, 345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Han X., Sterling H., Chen Y., Saginario C., Brown E. J., Frazier W. A., Lindberg F. P., Vignery A. (2000) CD47, a ligand for the macrophage fusion receptor, participates in macrophage multinucleation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 37984–37992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee S. H., Rho J., Jeong D., Sul J. Y., Kim T., Kim N., Kang J. S., Miyamoto T., Suda T., Lee S. K., Pignolo R. J., Koczon-Jaremko B., Lorenzo J., Choi Y. (2006) v-ATPase V0 subunit d2-deficient mice exhibit impaired osteoclast fusion and increased bone formation. Nat. Med. 12, 1403–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kukita T., Wada N., Kukita A., Kakimoto T., Sandra F., Toh K., Nagata K., Iijima T., Horiuchi M., Matsusaki H., Hieshima K., Yoshie O., Nomiyama H. (2004) RANKL-induced DC-STAMP is essential for osteoclastogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 200, 941–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim K., Lee S. H., Ha Kim J., Choi Y., Kim N. (2008) NFATc1 induces osteoclast fusion via up-regulation of Atp6v0d2 and the dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP). Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 176–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takayanagi H., Kim S., Koga T., Nishina H., Isshiki M., Yoshida H., Saiura A., Isobe M., Yokochi T., Inoue J., Wagner E. F., Mak T. W., Kodama T., Taniguchi T. (2002) Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev. Cell 3, 889–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herrera B. S., Ohira T., Gao L., Omori K., Yang R., Zhu M., Muscara M. N., Serhan C. N., Van Dyke T. E., Gyurko R. (2008) An endogenous regulator of inflammation, resolvin E1, modulates osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. Br. J. Pharmacol. 155, 1214–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao L., Faibish D., Fredman G., Herrera B. S., Chiang N., Serhan C. N., Van Dyke T. E., Gyurko R. (2013) Resolvin E1 and chemokine-like receptor 1 mediate bone preservation. J. Immunol. 190, 689–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jacquin C., Gran D. E., Lee S. K., Lorenzo J. A., Aguila H. L. (2006) Identification of multiple osteoclast precursor populations in murine bone marrow. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Helming L., Gordon S. (2009) Molecular mediators of macrophage fusion. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 514–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Negishi-Koga T., Takayanagi H. (2009) Ca2+-NFATc1 signaling is an essential axis of osteoclast differentiation. Immunol. Rev. 231, 241–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aliprantis A. O., Ueki Y., Sulyanto R., Park A., Sigrist K. S., Sharma S. M., Ostrowski M. C., Olsen B. R., Glimcher L. H. (2008) NFATc1 in mice represses osteoprotegerin during osteoclastogenesis and dissociates systemic osteopenia from inflammation in cherubism. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3775–3789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cheng Y. J., Imperatore G., Caspersen C. J., Gregg E. W., Albright A. L., Helmick C. G. (2012) Prevalence of diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation among adults with and without diagnosed diabetes: United States, 2008–2010. Diabetes Care 8, 1686–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pihlstrom B. L., Michalowicz B. S., Johnson N. W. (2005) Periodontal diseases. Lancet 366, 1809–1820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bijlsma J. W., Berenbaum F., Lafeber F. P. (2011) Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet 377, 2115–2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Izumi Y., Aoki A., Yamada Y., Kobayashi H., Iwata T., Akizuki T., Suda T., Nakamura S., Wara-Aswapati N., Ueda M., Ishikawa I. (2011) Current and future periodontal tissue engineering. Periodontol. 2000 56, 166–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Serhan C. N., Chiang N., Van Dyke T. E. (2008) Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 349–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schett G., David J. P. (2010) The multiple faces of autoimmune-mediated bone loss. Nature Rev. Endocrinol. 6, 698–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boyle W. J., Simonet W. S., Lacey D. L. (2003) Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 423, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lorenzo J., Horowitz M., Choi Y. (2008) Osteoimmunology: interactions of the bone and immune system. Endocr. Rev. 29, 403–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hasturk H., Kantarci A., Goguet-Surmenian E., Blackwood A., Andry C., Serhan C. N., Van Dyke T. E. (2007) Resolvin E1 regulates inflammation at the cellular and tissue level and restores tissue homeostasis in vivo. J. Immunol. 179, 7021–7029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hartgers F. C., Vissers J. L., Looman M. W., van Zoelen C., Huffine C., Figdor C. G., Adema G. J. (2000) DC-STAMP, a novel multimembrane-spanning molecule preferentially expressed by dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 3585–3590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yuan J., Akiyama M., Nakahama K., Sato T., Uematsu H., Morita I. (2010) The effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites on osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 92, 85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Garcia C., Boyce B. F., Gilles J., Dallas M., Qiao M., Mundy G. R., Bonewald L. F. (1996) Leukotriene B4 stimulates osteoclastic bone resorption both in vitro and in vivo. J. Bone Miner. Res. 11, 1619–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hikiji H., Ishii S., Yokomizo T., Takato T., Shimizu T. (2009) A distinctive role of the leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 in osteoclastic activity during bone loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 21294–21299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ohira T., Arita M., Omori K., Recchiuti A., Van Dyke T. E., Serhan C. N. (2010) Resolvin E1 receptor activation signals phosphorylation and phagocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3451–3461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Takahashi N., Maeda K., Ishihara A., Uehara S., Kobayashi Y. (2011) Regulatory mechanism of osteoclastogenesis by RANKL and Wnt signals. Front. Biosci. 16, 21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hwang S. Y., Putney J. W., Jr. (2011) Calcium signaling in osteoclasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 979–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Matsumoto M., Kogawa M., Wada S., Takayanagi H., Tsujimoto M., Katayama S., Hisatake K., Nogi Y. (2004) Essential role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in cathepsin K gene expression during osteoclastogenesis through association of NFATc1 and PU. 1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45969–45979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yagi M., Ninomiya K., Fujita N., Suzuki T., Iwasaki R., Morita K., Hosogane N., Matsuo K., Toyama Y., Suda T., Miyamoto T. (2007) Induction of DC-STAMP by alternative activation and downstream signaling mechanisms. J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 992–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Beals C. R., Sheridan C. M., Turck C. W., Gardner P., Crabtree G. R. (1997) Nuclear export of NF-ATc enhanced by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Science 275, 1930–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Martin T. J., Sims N. A. (2005) Osteoclast-derived activity in the coupling of bone formation to resorption. Trends Mol. Med. 11, 76–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cao X. (2011) Targeting osteoclast-osteoblast communication. Nat. Med. 17, 1344–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Feng X., McDonald J. M. (2011) Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 6, 121–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]